Abstract

There are disparities in the prevalence of childhood obesity for children from low-income and minority households. Mixed-methods studies that examine home environments in an in-depth manner are needed to identify potential mechanisms driving childhood obesity disparities that have not been examined in prior research. The Family Matters study aims to identify risk and protective factors for childhood obesity in low-income and minority households through a two-phased incremental, mixed-methods, and longitudinal approach. Individual, dyadic (i.e., parent/child; siblings), and familial factors that are associated with, or moderate associations with childhood obesity will be examined. Phase I includes in-home observations of diverse families (n=150; 25 each of African American, American Indian, Hispanic/Latino, Hmong, Somali, and White families). In-home observations include: (1) an interactive observational family task; (2) ecological momentary assessment of parent stress, mood, and parenting practices; (3) child and parent accelerometry; (4) child 24-hour dietary recalls; (5) home food inventory; (6) built environment audit; (7) anthropometry on all family members; (8) an online survey; and (9) parent interview. Phase I data will be used for analyses and to inform development of a culturally appropriate survey for Phase II. The survey will be administered at two time points to diverse parents (n=1200) of children ages 5–9. The main aim of the current paper is to describe the Family Matters complex study design and protocol and to report Phase I feasibility data for participant recruitment and study completion. Results from this comprehensive study will inform the development of culturally-tailored interventions to reduce childhood obesity disparities.

Keywords: Childhood Obesity Disparities, Mixed-Methods, Ecological Momentary Assessment, Home Environment, Minority, Low-income

INTRODUCTION

While the prevalence of childhood obesity may have started to plateau for some groups of children,1–5 other groups such as children from low-income, minority, or immigrant households are experiencing disparities in childhood obesity.4–7 Given the known health risks,8–14 societal burden,15 and healthcare costs15 associated with childhood obesity, addressing childhood obesity disparities is of high importance.

Childhood obesity disparities may in part be linked to unanswered questions regarding the home environments of racially/ethnically and socioeconomically diverse children. Although prior research has identified some important factors within the home environment that are protective for childhood obesity risk, there are important limitations and unanswered questions that still exist. First, research has shown that frequent family meals,16–19 non-controlling parent feeding practices,20,21 healthful food availability/accessibility in the home,20 and authoritative parenting style21–25 are associated with more healthful dietary intake (e.g., fruit/vegetables),26–28 less consumption of sugar-sweetened drinks and fast food,29 and fewer weight control behaviors30–33 in youth. However, many of the above findings have been inconsistent across studies with minority and low-income families.34,18,31,35 Second, the majority of studies have assessed key familial variables such as parent stress or parent feeding practices as static variables however, there may be day-to-day changes in parent stress levels or fluctuations in parent feeding practices that require measurement of intraindividual (i.e., occurring within the individual) processes. Using innovative technologies such as, ecological momentary assessment (EMA) will help pinpoint within- and between-day fluctuations in parenting practices or parent stress levels to identify nuances within the home environment that amplify or exacerbate childhood obesity risk. Third, analyses typically have not included multiple family members. Dyadic and familial- level analyses may create a more refined picture of the home environment and allow for analyses that disentangle risk and protective factors for childhood obesity.36,37 Fourth, many prior studies have been limited by cross-sectional designs, retrospective measures, and lack of objective measurements of dietary intake and physical activity.38 These limitations may partially explain why childhood obesity interventions that draw from these designs have had limited success.39

The Family Matters study was designed in direct response to these prior limitations in the field and in response to the NIH Strategic Plan for Obesity Research,40 which recommends research to identify common and unique risk and protective factors across and within racial/ethnic subgroups to inform the development of interventions to prevent childhood obesity and reduce childhood obesity disparities. The Family Matters study was specifically designed to: (a) examine in-depth the home environments of diverse families (n = 150) using innovative mixed-methodologies (e.g., EMA, video-recorded direct observations, qualitative interview) to identify novel risk and protective factors for childhood obesity, and (b) examine these factors longitudinally within a large diverse sample (n = 1200 African American, American Indian, Hispanic/Latino, Hmong, Somali, and White families) to identify potential explanatory mechanisms for childhood obesity disparities.

Given the unique nature of the Family Matters study design, and its potential utility for future research, the main aims of this paper are to: (1) provide a comprehensive overview of the complex study design and protocol and (2) report Phase I feasibility data for participant recruitment and study completion.

Theoretical Framework

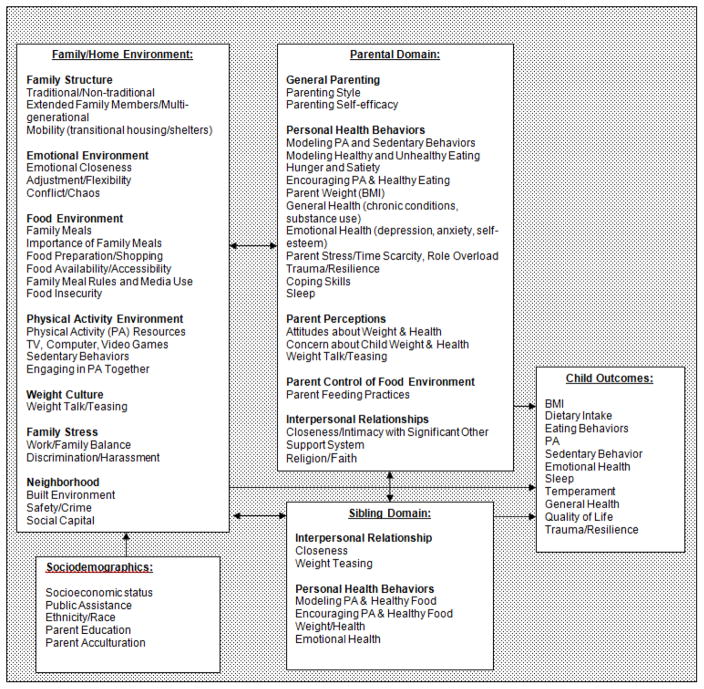

Family Systems Theory41,42 is the theoretical framework guiding the study design, hypotheses, and analyses. Family Systems Theory recognizes multiple levels of influence on a child’s weight and weight-related behaviors. Figure 1 illustrates the multiple familial levels within the home environment that may reciprocally influence child health behaviors and weight status. The family environment is the most proximal level of influence on child health behaviors and includes key variables such as parental control/restriction of the food environment, family meals, weight talk/teasing, sibling and parental modeling of health behaviors, and familial beliefs and practices. These parent, sibling, and familial factors ultimately influence child eating behaviors, physical activity patterns, and weight status.

Figure 1.

Individual, Dyadic, and Familial Influences on Childhood Obesity: Family Matter’s Study Theoretical Model

METHODS

Design Overview

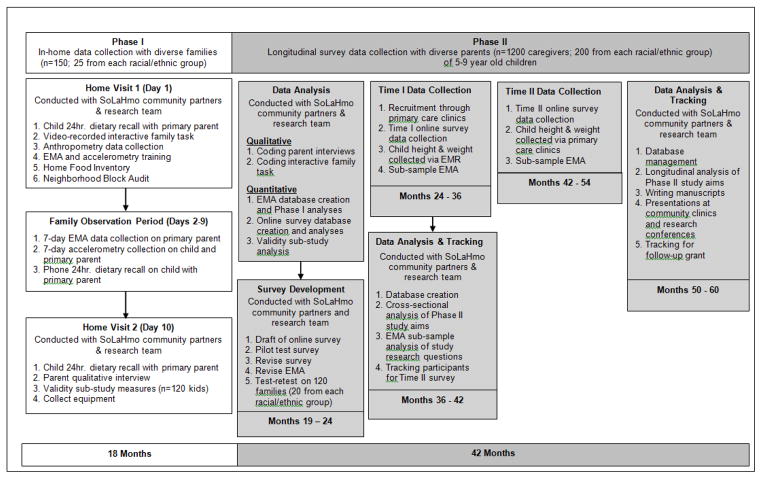

Family Matters is a 5-year incremental (Phase I = 2014–2016.; Phase II = 2017–2019), mixed-methods (e.g., video-recorded tasks, EMA, interviews, surveys) longitudinal study designed to identify novel risk and protective factors for childhood obesity in the home environments of racially/ethnically and socioeconomically diverse children. Figure 2 shows the timeline and accompanying tasks for each Phase of the study. Phase I of the study concluded in December 2016 and Phase II of the study began in January 2017.

Figure 2.

Family Matters Phase I and II Study Components and Timeline

In Phase I, a mixed-methods analysis of the home environments of 150 families with children ages 5–7 years old (n=25 African American, American Indian, Hispanic/Latino, Hmong, Somali, and White families) was conducted to identify individual, dyadic, and familial risk and protective factors for childhood obesity. A ten-day in-home observation was conducted with each family, including two in-home visits and an eight-day direct observational period. In-home observation components included: (1) an interactive observational family task43 using a family board game with activities around family meal planning, meal preparation, and family physical activity to measure family functioning and parenting practices; (2) EMA44 surveys measuring parent stress, mood, parent feeding practices, food preparation, parent modeling of eating and physical activity, and child dietary intake, physical activity, and sedentary behaviors; (3) child and parent accelerometry; (4) child 24-hour dietary recalls; (5) a home food inventory; (6) built environment block audit; (7) objectively measured height and weight on all family members; (8) a parent-completed online survey; and (9) a parent interview (see Table 1). A stratified random sampling design was used in Phase I. The sample was stratified by weight status and race/ethnicity to recruit overweight/obese (BMI ≥85%ile) and non-overweight (BMI >5%ile and <85%ile) children within each of the six racial/ethnic categories to identify potential weight- or ethnic/race-specific home environment factors related to obesity risk. Thus, within each racial/ethnic group (n=25 participants) approximately half (12 or 13) of the participants were non-overweight and approximately half were overweight/obese. One limitation of this stratification may be that including both overweight and obese youth in the same weight status category may not allow for differentiation of home environment factors/mechanisms that are specific to overweight risk versus obesity risk in children. Data from the in-home observations are currently being used for analytic purposes and for developing the survey for Phase II.

Table 1.

Phase I In-Home Visit components

| In-Home Visit Component | Procedure | How Measure Will be Used in Analyses |

|---|---|---|

| Anthropometry | Weight was measured on all family members in duplicate on a portable digital scale (Seca 869 model) and recorded to the nearest 0.1 kg. If the two measures differed by more than 0.5 kg, a third measure was obtained. Height was measured in duplicate, using a portable stadiometer (Seca 217 model) and recorded to the nearest 1.0 cm. If the two measures differed by more than 0.5 cm, a third measure was obtained.76,77 | Child heights and weights will be converted to child body mass index (BMI) percentile, based on Centers for Disease Control (CDC) criteria.78 Adult heights and weights will be converted into BMI, based on CDC guidelines.79 |

| 3-day 24-hour Dietary Recalls—NDSR | Using the Nutrition Data System for Research80 (NDSR, three 24-hour dietary recalls)81 were conducted with the primary caregiver to assess child dietary intake (2 weekdays and 1 weekend day).82–84 Recalls were conducted in-person (first/last home visit) and over the phone (between visits) in the parent’s language with a certified staff member.85,86 | The NDSR system aggregates foods into subgroups, and nutrient profiles are provided per day and per meal. Daily intake will be averaged to provide an overall diet profile for 5–7 year old children; NDSR records will also be used to create Healthy Eating Index-2010 scores.87 |

| Accelerometry | Child and parent physical activity level was evaluated using an accelerometer (Actigraph GT1M model, Fort Walton Beach, FL).88–91 Children and the primary caregiver wore the accelerometer over the 8-day observation period.92,93 Standardized re-wear protocol from previous research was followed (i.e., minimum=4 days; 1 weekend, 3 weekdays; 8 waking hrs./day).94 | Accelerometers were set to collect data in 15 second epochs. Outcome variables include: total time in sedentary behavior; total time in moderate and vigorous physical activity; percent of time spent in moderate and vigorous physical activity. |

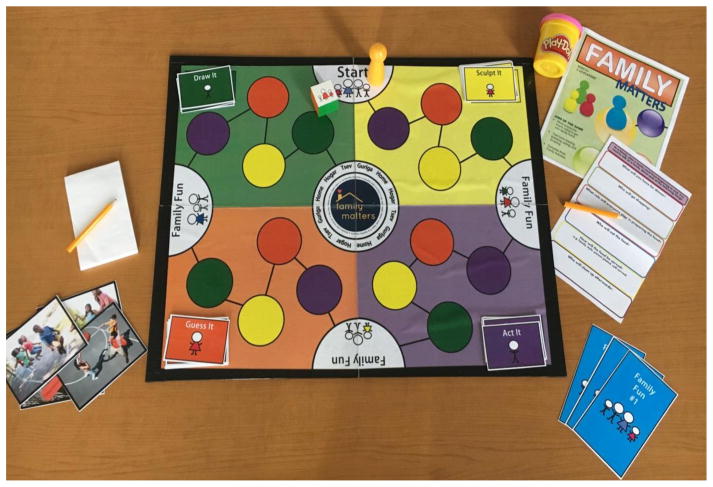

| Interactive Family Task Board Game | A direct observational interactive family task95 in the form of a board game was created for the study. The interactive family task assessed family communication, problem-solving skills, and relationship quality.95 The board game was played by all family members present at the home visit. A family game token was moved around the board and families had to complete challenges after every roll (e.g., Draw It, Sculpt It, Act It, Guess It). Additionally, there were three family-level tasks/activities on the board game that each family had to stop at and complete before they could move forward, including: 1) planning a family meal; 2) food preparation of a trail mix; and 3) planning a family physical activity outing. The task was video-recorded in order to code family interaction patterns.96–98 See Figure 3. | The Iowa Family Interaction Scale (IFIRS)99 will be used to quantitatively code the family interaction task. The IFIRS is a quantitative behavioral coding system used in direct observational research99,100 to measure behavioral and interpersonal interactions (e.g. parenting style, communication, hostility, relationship quality) between family members.99 |

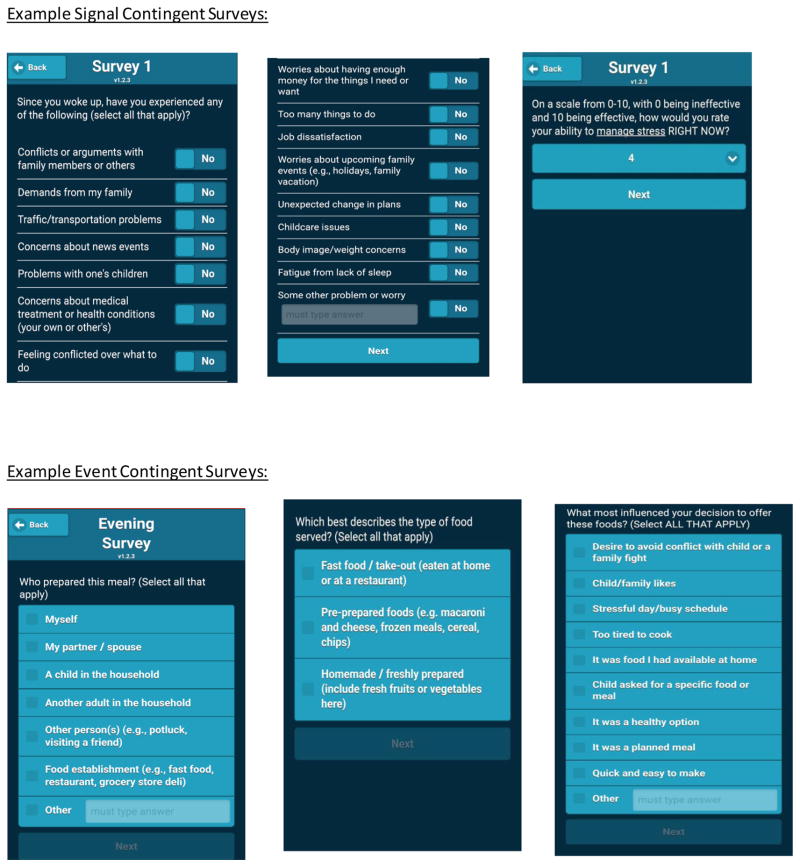

| Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) | Using an iPad mini, parents received signal, event, or end-of-day contingent EMA text messages multiple times throughout the day that included a link to an online survey. Signal contingent recordings were researcher-initiated and were used in a stratified random manner so that each parent was prompted (via a beep or vibration) to fill out a survey four times a day, within a three-hour time block (e.g., 7–10am, 11–2pm, 3pm–6pm, 7–10pm) that would expire after 1 hour. The signal contingent recordings allowed for examining different contexts that occurred day-to-day, moment-by-moment, in families’ lives. Questions asked on the signal contingent surveys included parent modeling of eating, physical activity and sedentary behavior, parent stress and mood levels, and child eating, physical activity and sedentary behaviors. Event contingent recordings were self-initiated by parents whenever an eating occasion occurred with the child. Parents were asked to fill out information about the type of food served at the meal, what the child actually ate, parent feeding practices, child eating behaviors, pickiness, meal atmosphere, food preparation and planning, and other meal logistics (e.g., who was at the meal, how long it lasted). The end-of-day recording was completed prior to sleep to capture any events not reported since the last recording, and to get end of day measures. All EMA responses were time-stamped. Participants’ were assigned additional days of EMA if several EMA prompts were missed within a day to obtain a minimum of eight full days of EMA data. The minimum requirement was for parents to respond to at least 2 signal contingent, 1 event contingent, and 1 end-of-day EMA message (total=4) per day. See Figure 4. | EMA44,101 measures will be used to capture day-to-day fluctuations in parent stress, mood and parenting practices. Items used in EMA data capture are based on highly validated (r=.80–.92)102,103 measures of stress (2 items with sub-items), mood (1 item) and parenting practices (8 items with sub-items).102,103 EMA measures will be evaluated within- , between- and across-days in cross-sectional, cross-lagged, and other longitudinal analyses. |

| Home Food Inventory | Valid home food inventories (HFI)104,105 were adapted to create a single instrument that could be used across racial/ethnic groups to measure household-level food availability and accessibility. The HFI was completed during the first home visit by a research team member. HFI items are listed in a checklist format with yes/no options. Team members were instructed to look for HFI foods in all areas of the home where food was stored, including the refrigerator/freezer, pantry, cupboard, etc. | The HFI will be used to evaluate the availability and accessibility of healthy foods (e.g., fruits, vegetables) and low-nutrient dense foods (e.g., sugar sweetened beverages). A validated obesogenic score104 will be created – the score is a sum of unhealthy foods (e.g., candy, chips) in the home, with a higher score indicating a more obesogenic environment. |

| Block Audit | The block audit was completed during the first home visit by trained and reliable research staff.106 Measures included available green space (e.g., yard, nearby parks, playground equipment, fences), safety hazards (e.g., broken windows, burned buildings, people arguing on the street, bars on windows), condition of residential grounds, the presence and condition of sidewalks, amount of traffic, and proximity to various businesses (e.g., convenience store, grocery store, coffee shop). | Walkability of neighborhood, nearest green space, nearest grocery store, nearest fast food establishment, neighborhood conduciveness to do physical activity, and neighborhood safety scores will be created and used in analyses.107–109 |

| Interview | A qualitative interview was conducted with the parent/primary guardian during the second home visit by trained research staff. 65 Interviews were conducted in the participant’s preferred language (e.g., English, Spanish, Hmong, Somali).65 Interview questions95 were directed toward understanding individual, dyadic, and familial norms around physical activity and eating, family routines (e.g., meal preparation, family meals), family weight culture (e.g., weight talk/teasing), cultural beliefs (e.g., beliefs about food, physical activity, body image) and each family member’s role in the home related to eating and physical activity.110,111 | Using Nvivo software, qualitative themes will be identified across family meals, eating patterns, physical activity, and weight conversations. Deductive content analysis, inductive content analysis, or grounded theory qualitative analysis will be used to code the parent interviews depending on the research question.65 |

| Online Survey | Survey development procedures used in prior research17,49,50,67 were used to create the Phase I survey. All survey items were drawn from preexisting standardized measures before creating new items. Standardized measures of the home food environment (e.g., food security,112 family meals113–115), physical and sedentary activity,116,117 family emotional atmosphere (e.g., communication, conflict, weight talk118–120), interpersonal relationships (e.g., parenting style, sibling relationships121), family structure, family stressors (e.g., work/family balance122), and acculturation123–127 were included. Questions regarding parents, significant other, siblings, family functioning,128 and target child were also included to allow for addressing household-level factors. | Survey measures will be used to explore relationships between home environment factors including, the home food environment, family interpersonal quality, family stressors, and acculturation with study outcome measures of child weight status and child diet quality. |

In Phase II, a different group of diverse parents of children ages 5-9 years old (total n=1200) will be recruited. The sample will be stratified by race/ethnicity (n=200 in each racial/ethnic group) only. The sample will not be stratified by weight status because it is expected that we will recruit a normal distribution of children across weight status categories. A survey, developed from the Phase I findings, will be administered to the 1200 parents/primary caregivers. Test-retest reliability analysis will be conducted with 120 parents (20 from each racial/ethnic group). Additionally, EMA will be revised from Phase I and utilized in about half (n=600) of the Phase II participants (i.e., those who meet eligibility criteria of having three or more family meals per wk.). The survey and EMA will be administered at two time points, 18-months apart to a large diverse sample to identify potential risk and protective factors for childhood obesity. The University of Minnesota’s Institutional Review Board Human Subjects Committee approved all protocols used in both phases of the Family Matters study.

Study Recruitment and Participant Tracking

Eligibility criteria

Study inclusionary criteria for both study phases includes: children ages 5–7 (Phase I) and 5–9 (Phase II) years old with no medical problem precluding study participation (e.g., disease altering diet or physical activity, serious mental illness), a BMI >5th %ile45 in the target child’s electronic medical records (EMR) not more than three months old, speak English, Spanish, Hmong and/or Somali, live full-time with the parent completing the study, and parent or child not currently participating in a weight management program. Children ages 5–9 years old were intentionally recruited for this study because developmentally they are becoming more responsible for decision making about dietary intake and physical activity behaviors as they start school, while their parents are simultaneously becoming less directly involved with their weight-related behaviors.46

Recruitment

In both phases, eligible children/parents are recruited from primary care clinics within Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota. Primary care clinics offer an excellent setting for study recruitment, in that they serve a high proportion of low-income and minority children, have direct access to parents, and reach participants in a familiar environment. In both phases, potential participants receive a follow-up phone call (in their own language) by a research team member matching their race/ethnicity one to two weeks after recruitment letters are sent from their clinic to confirm receipt of recruitment letter, answer any questions, review eligibility requirements and invite study participation.

Tracking

Phase II of the study is designed for follow-up to examine longitudinal, bidirectional predictors of child overweight/obesity and mechanisms that increase childhood obesity disparities. A dual tracking system via primary care clinics and the REDCap47 data capture system will be used. Primary care clinics have a built-in tracking system. At all clinic visits, parents are asked to give updated contact information. The clinics are invested in keeping this information accurate (e.g., appointment scheduling, communicating lab results, medical billing). Additional tracking methods include: (1) participant’s home phone, cell number(s), and e-mail addresses will be collected, in addition to contact information on relatives and friends ; (2) six-, twelve-, and eighteen- month tracking letters that include a study newsletter, giveaway (e.g., calendar, stickers, magnets, sticky notes), and request for contact information updates; (3) Facebook and other online tracking services (e.g., PeopleFinder.com, LexisNexis) will be used to locate hard-to-reach participants.

Procedures and Data Collection

Phase I: In-home observational data collection (yrs. 1–2; 2014–2016)

Families of eligible 5–7 year old children participated in two in-home visits over a 10-day period (Figure 2). The first home visit (day 1) included consenting/assenting, completion of the first 24-hour child dietary recall, video-recorded family interactive task, home food inventory, built environment block audit, and EMA and accelerometry training (Table 1). All study materials were translated into Spanish, Somali, and Hmong, and bilingual staff were available at all visits, allowing families to participate in their preferred language. Between home visits (days 2–9), research staff called the primary caregivers to conduct one 24-hour child dietary recall and to check on child and parent accelerometry. The parent also completed EMA surveys during this time. The second home visit (day 10) included conducting the final dietary recall, parent interview (at second home visit to avoid sensitizing families to the purpose of study), collection of accelerometry data, and incentive distribution. Because of the level of study involvement required, families were compensated with the iPad mini used to record EMA data (~$300) and additional gift card opportunities (up to $100) if all elements of the study were completed (e.g., all days of EMA, all three dietary recalls). This also increased the likelihood that the equipment was not misused.

Community-engaged process

This study included a community-engaged process with a community-based research48 team named SoLaHmo (stands for Somali, Latino and Hmong) Partnership for Health and Wellness. SoLaHmo and other community team members bring cultural expertise and experience conducting research “with” participants rather than “on” participants, while research team members bring expertise in research methods. SoLaHmo partnered with the UMN research team throughout Phase I on recruitment, survey development/translation/pilot testing, in-home data collection, coding parent interviews, and translating new survey items for the Phase II survey. They will continue to collaborate on dissemination of Phase I results and in carrying out Phase II.

Survey development (yr. 2; 2016)

Qualitative and quantitative data collected during in-home observations in Phase I guided survey development in Phase II. Qualitative data coded from the parent interviews and the video-recorded interactive tasks led to the identification of new important constructs to assess in Phase II such as: intergenerational transmission of family meal practices, social capital, immigrant trauma, family routines, and parental perceptions of their role during family meals. In addition, psychometrics from the online survey and EMA surveys were run to identify survey items for Phase II that were salient and performed well in Phase I. Furthermore, a validity sub-study was conducted on child BMI, dietary intake, and physical activity to compare parent proxy-report measures to gold-standard measures collected in Phase I to inform survey development for Phase II.

Survey development procedures used in our prior research17,49,50 were used to create the final Phase II survey including: (1) compilation of a draft survey based on our theoretical framework, a literature review of existing standardized measures, pilot testing, data collected from Phase I in-home observations, and SoLaHmo partners’ input; (2) translation of the survey into Spanish, Hmong, Somali by research staff and SoLaHmo team members; (3) review for language accuracy and cultural appropriateness by SoLaHmo team members; (4) revision of survey; (5) test-retest assessment with families (n=120; 20 from each racial/ethnic group); and (6) evaluation of scale psychometrics. All survey items were drawn from preexisting standardized measures before creating new items.

Validity sub-study (yr. 2; 2016)

To establish validity of self-report measures of dietary intake and physical activity to be used in the Phase II longitudinal survey, a validity sub-study was conducted with 77 participants (12–13 parents per each racial/ethnic group). Correlations between: (1) objectively measured 24hr. dietary recalls and self-reported child dietary intake51–53 and (2) objectively measured physical activity via accelerometry and self-reported child physical activity54,55 were run. Objective and self-reported fruit (r= 0.88), vegetable (r=0.25), and sugar-sweetened beverages (r=0.20) correlations ranged from low to moderately high, which matches or exceeds prior published validity studies on dietary intake.56,57 Objective and self-reported mild, moderate, and vigorous physical activity were low to moderately correlated (range r = 0.10–0.30), which is equivalent to other published validity studies on physical activity.58,59

Phase II: Longitudinal survey data collection (yrs. 3–5; 2017–2019)

For Phase II of the study, parents/primary caregivers of eligible 5-9 year old children will be recruited to participate in the study. Survey data collection follows the Dillman method,60 which utilizes several contacts in varying modes to attain high response rates including: mailing recruitment letters in brightly colored envelopes, using online survey methods, contacting potential participants at least five times, and allowing participants to complete the survey via phone if they prefer. SoLaHmo team members and culturally- matched research staff conduct all phone calls.

EMA data are also being collected on a sub-set of eligible participants in Phase II. Because EMA data collection went smoothly in Phase I, an exploratory aim was added to Phase II to embed EMA data collection within a longitudinal study with a larger sample size across two time points. Adding this component increases the ability to identify weight-related momentary decisions/behaviors that may be associated with obesity risk over time and across contexts. Because a main focus of this exploratory aim is to identify protective factors related to having regular family meals, families need to endorse having three or more family meals per week to be eligible to participate in EMA. Both the online survey and EMA data collection are being conducted at baseline and 18-months later. Participants are consented and sign HIPPA forms online before initiating the survey or EMA.

Measures

Phase I measures

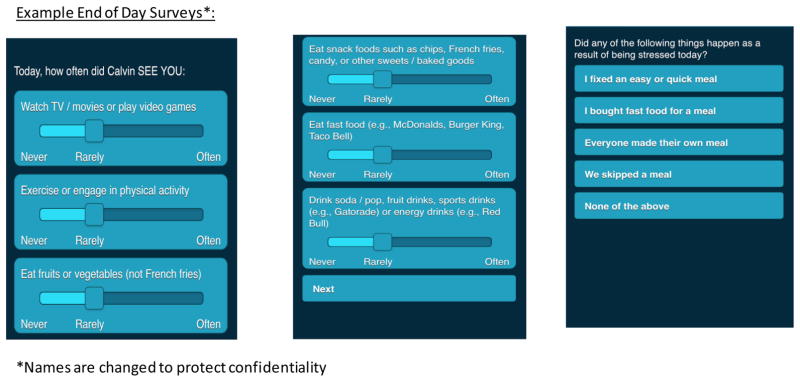

Measures used in Phase I of the study including the video-recorded task, EMA, dietary recalls, home food inventory, accelerometry, block audit, anthropometrics, parent interview and survey are described in Table 1. Additionally, a picture of the Family Matters board game is in Figure 3 and examples of EMA screen shots are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 3.

Family Interactive Task Board Game

Figure 4.

EMA Survey Question Examples

*Names are changed to protect confidentiality

Phase II measures

Measures used in Phase II including child weight, survey measures and EMA are described in Table 2. Examples of EMA screen shots are shown in Figure 4.

Table 2.

| Measures | Description |

|---|---|

| Electronic Medical Records | |

| Child Body Mass Index z-score (BMIz) and Overweight Status | Child height and weight will be obtained through the child’s electronic medical their primary care clinic.45 BMI values will be computed according to the following formula: weight (kg)/height and age-specific percentiles will be calculated using Centers for Disease Control (CDC) guidelines and transformed into BMIz scores 78,129,130 Sex- and age-specific cutoffs will also be used to classify children as overweight/obese (BMI ≥85th %ile) or non-overweight (>5th BMI %ile <85th).129,131 |

| Survey Items | |

| Family Meals | |

| Family Meals Frequency and Routines | Family meal routines and meal frequency across breakfast, lunch, and dinner will be assessed in the current household and in the household the parent grew up in. Questions are adapted from prior studies35,132,133 study. |

| Importance of Family Meals | Family meal routines will be measured using a six-item scale adapted from the Family Rituals Questionnaire.35,134 |

| Reasons for Having Family Meals | Reasons for having family meals will be assessed. These questions were developed from results of the qualitative interviews in Phase I of the current study. |

| Meal Atmosphere and Media Use | Frequency of the use of electronics/media during family meals and rules surrounding use will be assessed. These questions were developed from results of the qualitative interviews and EMA in Phase I of the current study. |

| Dietary Intake | |

| Child and Parent Dietary Intake | Child dietary intake patterns will be measured using an adapted version of the Child Eating Habits Questionnaire (CEHQ)51–53 created for diverse samples.53 Fourteen food groups will be assessed.135,136 Parent dietary intake will be assessed using food frequency items used in previous studies.35,132 |

| Child and Parent Breakfast Intake | Child and parent breakfast frequency will be assessed, using items from prior studies.35 |

| Child and Parent Fast Food Intake | Parent and child fast-food intake will be evaluated based on questions adapted from a 22-item dietary screener.137 Parents will be asked the frequency at which they and their children eat at particular fast-food restaurants in a typical week. |

| Food Preparation | |

| Food Preparation | Parent barriers to planning and preparing meals will be assessed using questions adapted from a 9-item scale used to assess time and energy for meals.138 Attitudes surrounding food preparation using questions selected from a 10-item questionnaire114 and child involvement in food preparation will be measured.139 Time spent on food preparation for both the parent and the parent’s significant other will be measured using questions developed from the SLOTH model.140 |

| Food Preparation Resources | Resources in the home environment available for food preparation will be assessed using questions derived from the 41-item Food Preparation Checklist (FPC),115 these questions surround the availability of food preparation supplies in the home and the counter & table space available for food preparation and family meals.115 |

| Food Shopping | Parent’s attitude towards food shopping, frequency of food shopping, who does the shopping, where the majority of shopping takes place, and what drives this decision (e.g., proximity to home/work, price, service etc.), how often the child is involved in shopping, and the availability of transportation to their preferred grocery store will be asked.114,141 |

| Food Skills Confidence | Questions developed for this survey from Phase I will assess parent’s perceived confidence regarding kitchen/cooking skills. |

| Food Availability/Accessibility | |

| Socioeconomic Status (SES) and Public Assistance | SES will be measured by asking total household income and the sources of household income (e.g., wages from self, wages from other family members, public assistance).94 Use of specific public assistance programs will also be evaluated including SNAP, WIC, TANF, SSI, or MFIP and if child qualifies for free or reduced-priced school lunch. |

| Home Food Availability | Parents will be asked to self-report the availability and accessibility of particular foods in their home using questions adapted from the Home Food Inventory (HFI).142 |

| Neighborhood Food Availability | Access to food options, specifically fruits and vegetables will be measured, based on availability and accessibility of healthy and unhealthy foods in parent’s neighborhood.35 |

| Food Insecurity | Food insecurity will be assessed by using questions from the 6-item short form Household Food Security Scale.112 |

| Child Eating Behavior & Parent Feeding Practices | |

| Child Eating Behavior | The Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire (CEBQ)143 will be used to measure child eating behavior. |

| Parenting Feeding Practices and Parent Modeling of Eating Patterns | Parenting practices will be measured including: (a) parent feeding practices and (b) parent modeling of healthy eating behaviors. Parent feeding practices will be assessed using The Child Feeding Questionnaire (CFQ).144 In addition, overt and convert control will be assessed.145 Parent modeling questions are adapted from previous studies.132,146 |

| Child and Parent Physical Activity | |

| Child and Parent Physical Activity | Physical activity questions will be adapted from the Godin-Shepherd Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire.147 Parents will be asked the number of hours in a usual week they and their child participate in (1) strenuous exercise, (2) moderate exercise, and (3) mild exercise, examples will be given for each type of exercise. |

| Child and Parent Sedentary Activity | Child and parent sedentary behavior will be assessed by asking how many hours during the week and on the weekends they and their child spend doing sedentary activities (e.g., watching TV/DVDs, using a computer, smartphone and tablet use, playing video games).147 |

| Parent Support of Physical Activity | Items from the Activity Support Scale (ACTs)148 will be used to identify parent’s support and involvement in promoting their child’s physical activity and parent’s limiting of sedentary behaviors.148 Parent’s frequency of involvement in their child’s physical activity will be assessed based on questions developed based on the SLOTH model.140 |

| Resources for Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior | Resources for physical activity will be measured by the total number of physical activity items (e.g., sports equipment, swimming pool, exercise mats etc.) available in the home.149 Access to sedentary resources in the home environment (e.g., TV/DVDs, computers, smartphones, tablet use, video games) will also be assessed.149 Child access to these items specifically will be assessed by asking how many of them belong to the child and/or are in his/her room. |

| Built Environment | |

| Neighborhood Safety | Questions from the Perceived Safety and Exposure to Violence150 questionnaire will be asked. |

| Neighborhood Walkability | The Neighborhood Environment Walkability Scale-Youth (NEWS-Y)151 will be used to measure the participant’s neighborhood safety and accessibility for youth physical activity. |

| Social Capital | Indicators of social capital will be assessed based select questions from the Social Capital Benchmark Study (SCBS).152 |

| Family Mobility | Questions measuring family moves within the past year and the reasons for each move will be assessed using items from prior studies.118 |

| Child and Parent Health | |

| Child Physical Health and Sleep | Parents will be asked to rate their child’s overall health153 and the number of hours their child sleeps on a typical weekday and weeknight.154 |

| Child Behaviors | The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) will be used to assess child emotional health.155 The SDQ is a parent proxy measure of child mental health including, emotion, behavior, hyperactivity-inattention, peer and prosocial domains.155–157 |

| Child Temperament | The Children’s Behavior Questionnaire (CBQ)158 will be used to evaluate child temperament. |

| Parent Physical Health and Sleep | The SF-8 Health Survey153 will be used to assess parent overall general health. In addition, parent hours of sleep and substance use will be assessed.35 |

| Parent BMI | Parent BMI will be assessed by using parent’s reported height and weight159. Parent’s will be classified as normal weight (≥18.5 BMI ≤24.9) or overweight/obese (BMI ≥30), based on the CDC BMI descriptions.159,160 |

| Parent Eating/Weight Behaviors : Healthy | Parent satiety will be assessed based on questions from the Intuitive Eating Scale.161 Frequency of healthy eating behaviors (e.g., eating fruits/vegetables, watching portion sizes) will also be assessed.162 |

| Parent Eating/Weight Behaviors: Unhealthy | Parent use of unhealthy weight control behaviors (e.g., fasting, taking diet pills, using laxatives), binge eating, and dieting will be assessed.162,163 |

| Parent Body Satisfaction and Weight | Parent body satisfaction will be assessed using items from The Body Satisfaction Scale.35,164 Parent satisfaction with their own and significant other’s weight status will also be assessed. |

| Spouse/Significant Other Weight-related Beliefs and Behaviors | Similar questions asked of the parent regarding unhealthy weight control habits will also be asked regarding their significant other.162,163 |

| Parent Emotional Health | The Kessler-6 Mental Health Scale165 and GAD-7166 will be used to assess parent’s depressive and anxiety symptoms. The Rosenberg Self-Esteem (RSE) Scale167 will be used to evaluate parent’s self-esteem.167 The Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) will measure parent resilience.168 |

| Parent Social Support | Parent perceived social support will be measured using questions from the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support.151 A question from The Add Health Study: Wave IV169 will be used to assess parent’s religious support. |

| Family Functioning | |

| Parenting Style and Parental Support of Child | Parenting style will be assessed using questions from the Parent Practices Questionnaire.121 Parenting dimensions measured include authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive. Parent’s involvement in their child’s school will also be assessed.170 |

| Family Functioning | General family functioning will be assessed using an adapted version of the General Family Functioning Sub-scale from the Family Assessment Device (FAD).128 The Confusion, Hubbub, and Order Scale(CHAOS)120 will be used to evaluate the home atmosphere.120 |

| Stress, Role Overload | Parent stress level and exposure to stressful life events will be measured using questions from The List of Threatening Experiences Questionnaire (LTE-Q) .38,171 Additionally, using the Reilly’s Role Overload Scale,172 parent perception of time scarcity and ability to meet family member’s needs will be measured. |

| Work-Family Balance | Questions regarding both work-family conflict (WFC)and family-work conflict (FWC) will be asked122 to assess demands and balance of both work, family and their interactions. |

| Co-Parenting | Parent’s co-parenting relationship and roles will be assessed using the Parenting Alliance Inventory.173 |

| Relationship Quality | Parent relationship quality with their significant other will be measured based on questions from the PAIR Inventory.174 |

| Weight & Health Conversations | |

| Weight Conversations and Concern for Child Health/Weight | Parent weight and weight-related conversations will be examined using survey items from prior studies.118 Parent perception of child’s current weight status, concern for child’s current weight status, and concern for future weight status as an adult will be assessed using questions from prior studies.119,175 |

| Family and Parent Weight Talk | The Family Fat Talk Questionnaire 172(FFTQ) will be used to evaluate the parent’s experience with weight talk and teasing both in the family they grew up in and the family they have now.172 |

| Spouse/Significant Other Weight Talk | Weight conversations between spouse and significant other will be asked using items from prior studies.147 |

| Teaching About Nutrition | Parents will respond to questions from The Comprehensive Feeding Practices Questionnaire (CFPQ) 176 that are specifically related to whether or not parents teach nutrition information to their child. |

| Discrimination, Harassment and Trauma | |

| Parent and Child Discrimination | Parent and child perceived discrimination/harassment (e.g., appearance, race, religion, financial situation) will be assessed using questions from prior studies.177,178 Parents will be asked additional questions related to discrimination from The Everyday Discrimination Scale,179 which address how they are treated compared to others. |

| Parent Traumatic Events | Parent’s experience of trauma will be assessed using questions from the Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) Study.180 Parents will also be asked questions from The List of Threatening Experiences (LTE)171 regarding recent trauma and trauma within the last 12 months. |

| Child Trauma | Child experience with trauma over the last 12 months will be assessed using questions adapted from The Peri Life Events Scale.181 |

| Demographics, Socioeconomic Status | |

| Acculturation | Acculturation will be measured using questions adapted from the AHIMSA Acculturation Scale.182 |

| Demographics: Race/Ethnicity and Immigrant Status | Demographics including parent and child’s race/ethnicity and background will be asked.183–185 Parent’s will also be asked their if they were born in the United States and if not where they were born and how long they have lived in the U.S.183–185 |

| Demographics: Income | Total household income and the sources of income will be assessed.94,186 Parents will also be asked how difficult it is for them to live on their current level of income.147 |

| Demographics: Education and Work | Parents will be asked to report their own and their spouse/significant other’s highest level of education and current employment status. 147 |

| Assessment (EMA) Collected at Registration | Ecological Momentary |

| Participant Information | At registration participants will be asked to enter information such as their name, age, gender, and their child’s name. In addition, participants will be asked for their phone number and email address along with their preferred method of contact. |

| Family Meals | Participants will be asked what time they wake up, go to bed, and eat family dinners to determine when surveys will be sent. |

| EMA Questions for Daily Surveys | |

| Parent Stress | Parent stress measures are from the Daily Health Diary.38 Parents will be asked about their momentary level of stress (since they woke up, or since their last survey), the main sources of stress (e.g., a lot of work to get done at job or school, food insecurity, financial pressures), and their perceived ability to cope with stress.38 |

| Parent Mood/Depressive Symptoms | Parent momentary mood and depressive symptoms will be assessed using the Kessler-6.165 Parents will be asked if they have felt certain emotions (e.g., nervous, hopeless, restless) since their last survey, or since they woke up. |

| Survey Burden | After each daily survey, parents will be asked how difficult it was for them to complete that particular survey. |

| EMA Questions for Final Survey | |

| Parent Mood/Depressive Symptoms | Parent’s mood and depressive symptoms over the entire day will be evaluated in the evening survey using the Kessler-6. 187 |

| Child’s/Family Dinner Meal | Parents will be asked about specifics about the child’s/family meal including, the type(s) of food served at the meal, what the child actually ate, parent feeding practices, child eating behaviors, pickiness, meal atmosphere, food preparation and planning, and other meal logistics (e.g., who was at the meal, how long it lasted). These questions were developed from Phase 1 of the Family Matters study. |

| Parent Stress | In the final survey, parent momentary stress will be measured using the Daily Health Diary. 38 Parents will be asked about their level of stress, the main sources of stress, and their perceived ability to cope with stress. Exposure to particular stressors will be evaluated again by asking if they have experienced particular sources of stress (e.g., a lot of work to get done at job or school, food insecurity, financial pressures).38 |

| Meal Preparation | Parents will be asked about reasons for serving foods,114,188 who prepared the food,139 how long it took to prepare,35 whether it was planned, what types of foods were served, and why they were chosen for the meal.189,190 Types of food served will also be measured including, the overall type of food (e.g., fast food, homemade) and which food types were served at dinner. |

| Meal Atmosphere | To evaluate the atmosphere of the meal parents will be asked who was at the meal (parent and kids),191 where the meal took place (e.g., home, restaurant, other person's home), if they meal took place in their home. They will also be asked where in the home the meal occurred (e.g., around a table, on couch),113,192 what was happening during the meal (e.g., watching TV, conversation), and how parents would describe the meal atmosphere (e.g., neutral, chaotic, enjoyable).113,192 |

| Parent Feeding Practices | Parents will be asked about parent feeding practices engaged in at each meal using questions adapted from the Birch parent feeding practices scale144 including, restriction and pressure-to-eat. |

| Picky Eating/Food Fussiness | Using questions adapted from the Child Eating Behavior Questionnaire, child pickiness and food fussiness will be evaluated at each meal.143 |

| Parent Satisfaction with Child’s Eating | Parents will be asked how satisfied they were with how their child ate at each meal, based on items from the Child Eating Behavior Questionnaire.143 |

| Child Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior | Parents will be asked how often their child participated in physical activity or sedentary behaviors (e.g., watching TV/movies, video games, tablets, smartphones) throughout the day.102,188 |

| Survey Burden | To evaluate the overall survey burden for each day, parents will be asked how difficult it was for them to complete the surveys each day. |

STATISICAL ANALYSIS PLAN

Phase I Aims and Hypotheses

Phase I has both qualitative and quantitative aims. The qualitative aim is to identify thematic clusters of individual, dyadic, and familial factors (via interviews and interactive family task) in diverse home environments that are potential risk or protective factors for childhood obesity for analytic purposes and to inform Phase II survey development.

The quantitative aim is to examine how within-day and between-day fluctuations in parent stress, mood, and parenting practices (measured by EMA) relate to child weight and weight-related behaviors. The quantitative aim will evaluate the following hypotheses: (1) higher parental stress, depressed mood, or unsupportive parenting practices/modeling behavior at any given point in the day will be positively associated with unhealthful child behaviors (e.g., screen time, sugar sweetened beverage consumption) and negatively associated with child healthful behaviors (e.g., physical activity, fruit and vegetable intake) at a subsequent point during that same day, and (2) higher parental stress, depressive mood, and unsupportive parenting practices across the 8-day observation period will be positively associated with child unhealthful eating behaviors (e.g., high fat snacks, picky eating), restrictive and pressure-to-eat feeding practices by parents, and unhealthful food options served at meals (e.g., eat fast food for dinner) across the same observation period.

Phase I Analysis: In-home Observations with Diverse Families (n=150; 25 each race/ethnic group)

Qualitative analysis of in-home observations

Audio-recorded parent interviews from the in-home observations were transcribed verbatim and coded independently by two research team members using NVivo 10 software.61 Inductive Content Analysis62 was used to analyze qualitative transcripts.63–66 Data were organized using constant comparison, line-by-line coding until themes emerged.62,67 Inter-rater reliability was established at 95% between the coders; kappa = 0.80. Discrepancies in coded data were discussed between coders and the research team to reach 100% consensus.64,68 The data were organized into representative categories related to individual, dyadic, and familial risk and protective factors in the home environment until saturation occurred and were grouped into broad themes to highlight findings.68 The video-recorded interactive component of the family interview was quantitatively coded using the Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales (IFIRS). Inter-rater reliability was established at 95% between coders; kappa = 0.87. Discrepancies in coded data were discussed between coders and the research team until 100% consensus was reached.64,68 Themes identified based on the inductive content analysis and the IFIRS coding were used to identify specific content areas to be included in the survey developed for Phase II. Coded data is also being used for publishing mixed-methods papers.

Quantitative analysis of in-home observations

Phase I also includes EMA data analysis. To test the first hypothesis (within-day analyses), generalized estimating equations will be used to determine the association between daily parent stress and modeling health behaviors between 7am–3pm (independent variable) and child afternoon/evening health behaviors between 4pm–10pm (dependent variable), assessed by 24-hour dietary recalls, accelerometry, EMA child eating behaviors. Adjusted models will include the following covariates: parent and child sex, age, household income, and race. Since late afternoon EMA stress measures (from 3–6pm) could overlap, or be a consequence of, child afternoon health behaviors, we will conduct separate analyses to evaluate average parental stress between 7am–2pm. Repeated measures are available for both parental stress and child physical activity or healthful eating over all 8-days in Phase I. Regression analyses will use all 8-days of observations and generalized estimating equations, addressing correlated errors within children, will be used to estimate appropriate standard error measurements.

To test the second hypothesis (between-day analyses), generalized linear mixed models will be used to examine how parent stress level as a continuous random variable relates to child eating behaviors and parent feeding practices over time. Correlation tables and data visualization plots (e.g., matrix plots) will be used to assess the correlation structure between observations collected at the eight time points. Stress will be lagged and in a separate model the change (i.e., difference) will be used to evaluate between-day relationships with parent stress level and the change in parent stress level on child and parent behaviors. Participant random intercepts will be used to account for the repeated measure analysis, and adjusted models will include covariates described above.

Phase II Aims and Hypotheses

Phase II has two main aims, including: (1) examine individual, dyadic (i.e., parent/child; sibling), and familial risk and protective factors for predicting childhood obesity and other health behaviors (e.g., dietary intake, physical activity, sedentary behavior); and (2) examine whether and how race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status modify these associations. Cross-sectional and longitudinal hypotheses will be tested. Cross-sectional hypothesis include: parental support for physical activity and healthful eating (e.g., authoritative parenting style, non-controlling feeding practices, family meals, family support for physical activity, family level engagement in physical activity) in the home environment will differ by income and race/ethnicity. Longitudinal hypothesis include: differences in parenting style (e.g., authoritative vs. authoritarian), parenting practices (e.g., controlling vs. non-controlling feeding practices), parent mood and stress, and familial support for healthful eating and physical activity at time 1 will predict changes in child weight, dietary intake, and physical activity at time 2. Additionally, longitudinal associations will be modified by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status.

Phase II Analysis: Longitudinal Survey with a Diverse Parent Sample (n=1,200)

All analyses will begin by running descriptive statistics, frequency distributions, cross-tabulations and correlation matrices for all variables—allowing us to identify outliers, assess missing data and identify highly correlated covariates, which may cause estimation problems in our models. Based on our prior research, we expect little missing data; however, we will consider multiple imputation techniques if substantial missing data is identified.69

Cross-sectional analysis

The descriptive analysis described above will inform modeling assumptions and data validity, and multiple regression models will be used to estimate associations. Parental support for healthful eating and physical activity will be the dependent variables in separate regression models. Indicator variables for race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status (defined by parent highest level of education) will be included as independent variables in the regression models to assess the association between each racial/ethnic (or SES) group and the chosen aspect of the home environment. Linear regression models will be used when the support variables are continuous measures (e.g., number of days/week parent reports a given type of support). We will use logistic regression models in which the type of support is categorized as presence or absence (i.e., ever/never). We will explore a wide range of potential confounders in the models; especially parent BMI and child BMI. Due to the breadth of various immigration and acculturation experiences in the study sample, acculturation status70 (assimilation, separation, integration, and marginalization) will be modeled to account for processes (e.g., health-related) that may differ for parents and children who were born in the United States, recently immigrated, or who were foreign born but have been living in the United States for a greater length of time. Other analyses will explore the impact of family structure (single vs. dual headed households) on child support by including it as a predictor and effect modifier in regression models. Regression modeling assumptions (particularly, normality in linear regression models) will be evaluated to ensure validity of results.

Longitudinal analyses

The longitudinal hypothesis will be estimated using regression models (linear for continuous variables such as BMI z-score; logistic or log-binomial for dichotomous outcomes such as overweight). Independent variables in these models will include parenting style or practice variables. Separate cross-lagged regression models will be fit for each association of interest. All models will be adjusted for parent BMI as well as the dependent variable at time 1. For example, models assessing the impact of parenting style on child BMI at follow-up will adjust for BMI at baseline. To examine whether the associations are modified by race/ethnicity or SES, we will fit models that include interactions between the predictor of interest and race/ethnicity or SES.

Power Calculations

Power Analysis Phase I

To illustrate the power available for Phase I analyses, calculations are focused on the first quantitative hypothesis. Using our prior study data,71 we estimate the standard deviation of moderate or vigorous physical activity is 4.7 hrs./wk. These data suggest approximately half of the sample will fall in each of the low and high physical activity groups at the CDC recommended child physical activity guidelines (1 hour of physical activity per day),72 which provides 80% power to detect a difference of 2.4 hours per week of physical activity with a type I error rate of 0.05 (two-sided). These estimates are conservative and Aim 1 analyses will have greater power to detect effects due to the repeated measures nature of the data. Using the same standard deviation as above and assuming a physical activity correlation of 50% across days, we have 80% power to detect a difference of 1.8 hrs./week of PA between low and high stress individuals. Stata v12 was used for power calculations.

Power analysis Phase II

To illustrate the power available for Phase II analyses, calculations are focused on examining the association between parenting style and child BMI z-score at time 2. Assuming a type I error rate of 5% (2-sided), we have 80% power to detect a difference greater than 0.28 between any two parenting style categories (e.g., authoritative versus authoritarian) assuming an equal number of individuals in each category. To place this in context, a change of 0.28 in BMI z-score represents a change of approximately 1.6 lbs in a 4 foot tall, 50 lb, 6 year old boy. Although the main analysis is powered to allow examination of many secondary hypotheses, multiple comparison adjustments (e.g., Tukey HSD adjustments)73 will be employed to avoid inflated type I error rates. Assuming approximately equal numbers of each ethnic group, we have 80% power to detect a difference in BMI z-score between parenting style categories of 0.69 within a race/ethnic group. This corresponds to a change of approximately 3.7 lbs in a 4 foot tall, 50lb, 6 year old boy. Power calculations were performed using Stata v12.74,75

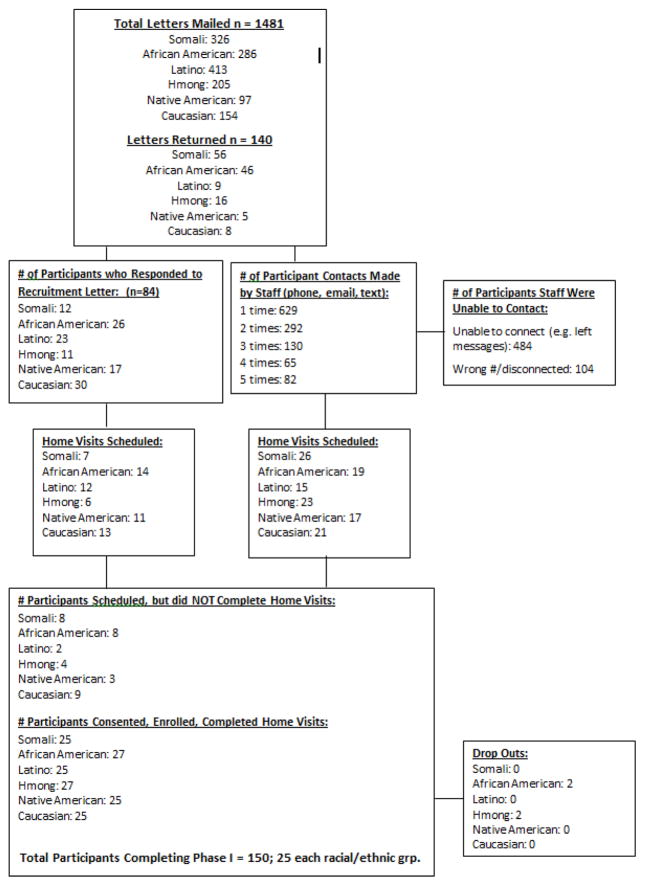

PROCESS DATA RESULTS OF PHASE I TO DATE

Based on the study design and recruitment protocol described above, high feasibility and participant compliance rates with recruitment and study completion have resulted for Phase I of the study. All 150 participants were recruited and completed Phase I of the study within the 18-month time period, with only four families dropping out of the study (Figure 5). Recruitment success rates for Phase I in-home visits varied by racial/ethnic group, with Caucasian, African American, Hispanic and Hmong families being the easiest to recruit and Native American and Somali families the most challenging. Additionally, certain groups were more likely to initiate a call to the research team for study participation (e.g., White, African American), while other groups required the research team to reach out to them via phone calls (e.g., Somali) for participation. For all components of the study, participants were highly compliant. For the EMA component of the study, 100% of participants competed all eight days of EMA data collection and met the minimum requirement per day (i.e., 2 signal contingent, 1 event contingent, 1 end-of-day contingent; total=4 EMA responses/day); on average, participants completed 7.4 surveys per day. For the dietary recall data collection, 97% (n=146) of children had complete dietary recall data (i.e., 2 weekdays, 1 weekend day; total = three 24hr. dietary recalls), with only four families completing just two of the three dietary recalls. Additionally, 100% of the home food inventories were completed. For the accelerometry data collection, 90% of children (n = 135) completed all eight days of accelerometry data collection and met the minimum wear time criteria (i.e., 1 weekend, 3 weekdays; 6 waking hrs./day). For the qualitative interviews and family interactive task, 100% of parents completed the interviews and the interactive family board game task (family members engaging in the task ranged from 2–8 people). For the block audit, 100% of the audits on the neighborhood were completed. Additionally, no iPad minis were stolen or broken during Phase I, and only 4 accelerometers were lost.

Figure 5.

Recruitment Flow Diagram

FAMILY MATTERS STUDY DESIGN SUMMARY AND DISCUSSION

Prior studies examining the association between the home environment and childhood obesity have mostly utilized retrospective measures, cross-sectional study designs, and not explored within- and between-day processes, and intraindividual variation of weight-related behaviors. These limitations have potentially masked mechanisms that may explain the ever widening disparities in childhood obesity by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. The Family Matters study was designed to address these limitations in the field by utilizing an incremental, mixed methods longitudinal approach with in-home observations and state-of-the art measures to provide a more refined picture of the home environment. Highly innovative aspects of the Family Matters study include:

Incremental mixed-methods approach

Phase I and II of the Family Matters study were designed to incrementally build upon each other. In Phase I, in-depth in-home observations were conducted to identify potential mechanisms driving childhood obesity disparities before creating the survey for the Phase II. This incremental approach will increase the likelihood of finding previously missed/unexplored racial/ethnic-specific home environment factors that can be targeted in interventions to reduce childhood obesity disparities. Furthermore, this incremental approach will facilitate capturing both the depth (qualitative) and breadth (quantitative) of potential risk or protective factors for childhood obesity in diverse families.

State-of-the-art measures such as, direct observation of interpersonal interactions through video-recorded tasks, ecological momentary assessment (EMA) of parental stress, mood, and parenting practices are being used, and qualitative interviews will provide a more refined picture of daily life within diverse households. For example, analyzing daily fluctuations in parent stress, mood, and parenting practices via EMA will allow for identifying times of the day that are more problematic for parents with regard to creating a healthy home environment that will inform optimal timing of delivery of intervention targets.

Using community-based research partners will increase the quality of the research and participant trust. Community-based team members are participating in Phase I and Phase II, including adapting and translating study materials; conducting home visits; participating in coding/ analyzing interview data; translating and pilot testing the survey; and interpreting and disseminating results.

Individual, dyadic, and familial factors will be assessed, allowing for more complex familial interactions to be examined. Results will provide a comprehensive picture of the home environments of diverse families to inform whether, and how, interventions need to be tailored to different population subgroups and family structures to reduce childhood obesity disparities. For example, if results show that African American families benefit from frequent family meals more than other groups, interventions should include more curriculum designed around increasing the frequency of family meals in the homes of African American children.

Overall, the Family Matters study was designed to utilize an incremental, mixed-methods longitudinal approach to identify potential risk and protective factors for childhood obesity in the home environments of diverse families. Results from Family Matters will inform the creation of interventions to be carried out in racial/ethnic and immigrant households to reduce childhood obesity disparities.

Acknowledgments

The Family Matters study is truly a team effort and could not have been accomplished without the dedicated staff who carried out the home visits, including: Awo Ahmed, Nimo Ahmed, Rodolfo Batres, Carlos Chavez, Mia Donley, Michelle Draxten, Carrie Hanson-Bradley, Sulekha Ibrahim, Walter Novillo, Alejandra Ochoa, Luis “Marty” Ortega, Anna Schulte, Hiba Sharif, Mai See Thao, Rebecca Tran, Bai Vue, and Serena Xiong.

FUNDING

This research is supported by grant number R01HL126171 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (PI: Berge). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: Authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bethell C, Simpson L, Stumbo S, Carle AC, Gombojav N. National, State and Local Disparities in Childhood Obesity. Health Affairs. 2010;29(3):347–356. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson DK. New perspectives on health disparities and obesity interventions in youth. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2009;34(3):231–244. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.NIH. Reducing health disparities among children: Strategies and programs for health plans. Washington DC: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogden C, Lamb M, Carroll M, Flegal K. Obesity and Socioeconomic status in children and adolescents: United Stated, 2005–2008. NCHS Data Brief. 2010;(51) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ogden C, Carroll M, Curtin L, Lamb M, Flegal K. Prevalence of high body mass index in US children and adolescents, 2007–2008. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;303(3):8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang YC, Orleans CT, Gortmaker SL. Reaching the healthy people goals for reducing childhood obesity: Closing the energy gap. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2012;42(5):437–444. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orsi C, Hale D, Lynch J. Pediatric obesity epidemiology. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2011;18(1):14–22. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e3283423de1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Popkin BM. Understanding global nutrition dynamics as a step towards controlling cancer incidence. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:61–67. doi: 10.1038/nrc2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whitaker RC, Wright JA, Pepe MS, Seidel KD, Dietz WH. Predicting obesity in young adulthood from childhood and parental obesity. New England Journal of Medicine. 1997;25(337):869–873. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709253371301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daniels SR. The consequences of childhood overweight and obesity. The Future of children / Center for the Future of Children, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation. 2006;16(1):47–67. doi: 10.1353/foc.2006.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merten MJ. Weight status continuity and change from adolescence to young adulthood: Examining disease and health risk conditions. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md) 2010;18(7):1423–1428. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gordon-Larsen P, The NS, Adair LS. Longitudinal trends in obesity in the United States from adolescence to the third decade of life. Obesity. 2009 doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pi-Sunyer FX. The obesity epidemic: Pathophysiology and consequences of obesity. Obesity Research. 2002;10(Suppl 2):97S–104S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stovitz S, Hannan P, Lytle L, Demerath E, Pereira M, Himes J. Child height and the risk of young-adult obesity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2010;38(1):74–77. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finkelstein EA, Trogdon JG, Cohen JW, Dietz W. Annual medical spending attributable to obesity: payer-and service-specific estimates. Health Affairs. 2009;28(5):w822–831. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.5.w822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berge J, Truesdale K, Sherwood N, et al. Beyond the dinnner table: Who's having breakfast, lunch and dinner family meals and which meals are associated with better preschool children's health? Pubilc Health Nutrition. doi: 10.1017/S1368980017002348. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berge JM, Rowley S, Trofholz A, et al. Childhood obesity and interpersonal dynamics during family meals. Pediatrics. 2014;134(5):923–932. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fulkerson JA, Neumark-Sztainer D, Hannan PJ, Story M. Family meal frequency and weight status among adolescents: Cross-sectional and five-year longitudinal associations. Obesity. 2008;16:2529–2534. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neumark-Sztainer D, Hannan PJ, Story M, Croll J, Perry C. Family meal patterns: associations with sociodemographic characteristics and improved dietary intake among adolescents. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2003;103(3):317–322. doi: 10.1053/jada.2003.50048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berge JM. A review of familial correlates of child and adolescent obesity: what has the 21st century taught us so far? International journal of adolescent medicine and health. 2009;21(4):457–483. doi: 10.1515/ijamh.2009.21.4.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rhee KE, De Lago CW, Arscott-Mills T, Mehta SD, Davis RK. Factors associated with parental readiness to make changes for overweight children. Pediatrics. 2005;116(1):e94–101. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berge JM, Wall M, Bauer KW, Neumark-Sztainer D. Parenting characteristics in the home environment and adolescent overweight: a latent class analysis. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md) 2010;18(4):818–825. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berge JM, Wall M, Loth K, Neumark-Sztainer D. Parenting style as a predictor of adolescent weight and weight-related behaviors. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;46(4):331–338. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Golan M, Crow S. Parents are key players in the prevention and treatment of weight-related problems. Nutrition reviews. 2004;62(1):39–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2004.tb00005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rhee KE. Childhood overweight and the relationship between parent behaviors, parenting style, and family functioning. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2008;615(12):11–37. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gable S, Lutz S. Household, parent and child contributions to childhood obesity. Family Relations. 2000;49(3):293–300. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gillman MW, Rifas-Shiman SL, Frazier AL, Rockett HRH, Camargo CA, Field AE, Berkley CS, Colditz GA. Family dinner and diet quality among older children and adolescents. Archives of Family Medicine. 2008;9:235–240. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.3.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neumark-Sztainer D, Hannan PJ, Story M, Croll J, Perry C. Family meal patterns: associations with sociodemographic characteristics and improved dietary intake among adolescents. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2003;103(3):317–322. doi: 10.1053/jada.2003.50048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eisenberg ME, Olson RE, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Bearinger LH. Correlations between family meals and psychosocial well-being among adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2004;158:792–796. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.8.792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neumark-Sztainer D, Eisenberg ME, Fulkerson JA, Story M, Larson NI. Family meals and disordered eating in adolescents: Longitudinal findings from Project EAT. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2008;162:17–22. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jacobs MP, Fiese B. H. Family mealtime interactions and overweight children with asthma: Potential for compounded risks? Journal of pediatric psychology. 2007;32(1):64–68. doi: 10.1093./jpepsy/jsl026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moens E, Braet C, Soetens B. Observation of family functioning at mealtime: A comparison between families of children with and without overweight. Journal of pediatric psychology. 2007;32(1):52–63. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsl011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Campbell KJ, Crawford DA, Ball K. Family food environment and dietary behaviors likely to promote fatness in 5–6 year-old children. International Journal of Obesity. 2006;30:1272–1280. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berge JM. A review of familial influences on child and adolescent obesity: What has the 21st Century taught us so far? International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health. 2010;21(4):546–561. doi: 10.1515/ijamh.2009.21.4.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berge JM, MacLehose RF, Loth KA, Eisenberg ME, Fulkerson JA, Neumark-Sztainer D. Family meals. Associations with weight and eating behaviors among mothers and fathers. Appetite. 2012;58(3):1128–1135. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davison KK, Birch LL. Childhood overweight: A contextual model and recommendations for future research. Obesity Reviews. 2001;2:159–171. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-789x.2001.00036.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berge JM, MacLehose R, Eisenberg ME, Laska MN, Neumark-Sztainer D. How significant is the 'significant other'? Associations between significant others' health behaviors and attitudes and young adults' health outcomes. The international journal of behavioral nutrition and physical activity. 2012;9:35. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dunton GF, Liao Y, Dzubur E, et al. Investigating within-day and longitudinal effects of maternal stress on children's physical activity, dietary intake, and body composition: Protocol for the MATCH study. Contemporary clinical trials. 2015;43:142–154. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2015.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stice E, Shaw H, Marti CN. A meta-analytic review of obesity prevention programs for children and adolescents: The skinny on interventions that work. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132(5):667–691. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.5.667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.National Institutes of Health Obesity Research Task Force. Strategic plan for NIH obesity research. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health; 2011. pp. 11–5493. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Whitchurch GG, Constantine LL. Systems theory. In: Boss PG, Doherty WJ, LaRossa R, Schumm WR, Steinmetz SK, editors. Sourcebook on family theories and methods: A contextual approach. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bertalanffy LV. Theoretical models in biology and psychology. In: Krech D, Klein GS, editors. Theoretical models and personality. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 1952. pp. 24–38. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Melby JN, Conger RD. The Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales: Instrument Summary. In: Kerig PK, Lindahl KM, editors. Family Observational Coding Systems: Resources for Systemic Research. Mahway, NJ: Lawrence Ehrlbaum Associates; 2001. pp. 33–58. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shiffman S, Stone AA, Hufford MR. Ecological momentary assessment. Annual review of clinical psychology. 2008;4:1–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barlow SE. Expert committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: summary report. Pediatrics. 2007;120(Suppl 4):S164–192. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2329C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hetherington E, Parke R. Child Psychology. Boston: McGraw-Hill College Inc; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grant number UL1TR000114 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciencces (NCATS) of the National Institutes of HEalth (NIH). 2012.

- 48.Berge JM, Mendenhall TJ, Doherty WJ. Using Community-based Participatory Research (CBPR) To Target Health Disparities in Families. Family Relations. 2009;58(4):475–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2009.00567.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Larson NI, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, van den Berg P, Hannan PJ. Identifying correlates of young adults' weight behavior: Survey development. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2011;35:712–725. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]