Abstract

The bacterial communities in a wide range of environmental niches sense and respond to numerous external stimuli for their survival. Primarily, a source they require to follow up this communication is the two-component signal transduction system (TCS), which typically comprises a sensor Histidine kinase for receiving external input signals and a response regulator that conveys a proper change in the bacterial cell physiology. For numerous reasons, TCSs have ascended as convincing targets for antibacterial drug design. Several studies have shown that TCSs are essential for the coordinated expression of virulence factors and, in some cases, for bacterial viability and growth. It has also been reported that the expression of antibiotic resistance determinants may be regulated by some TCSs. In addition, as a mode of signal transduction, phosphorylation of histidine in bacteria differs from normal serine/threonine and tyrosine phosphorylation in higher eukaryotes. Several studies have shown the molecular mechanisms by which TCSs regulate virulence and antibiotic resistance in pathogenic bacteria. In this review, we list some of the characteristics of the bacterial TCSs and their involvement in virulence and antibiotic resistance. Furthermore, this review lists and discusses inhibitors that have been reported to target TCSs in pathogenic bacteria.

Keywords: bacterial two-component signal transduction system, virulence and antibiotic resistance, inhibitors for kinases and response regulators

Introduction

Microbes are the most versatile living organisms on the planet. They can be found in environments where plants and animals cannot survive, such as in hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor or glaciers. Bacteria have developed a number of features (e.g., signal transduction systems) that allow crosstalk between the intracellular and extracellular environments. The bacterial repertoire for sensing environmental conditions includes regulatory proteins that bind to secondary metabolites or ions, resulting in increased affinity for specific regulatory DNA sequences. Examples of well-studied regulatory proteins include the Catabolite Regulatory Protein (CRP, which senses cyclic adenosine monophosphate accumulated under low availability of glucose) and Ferric Uptake Regulator (Fur, which binds to Fe2+) (Nixon et al., 1986; Hoch, 2000; Stock et al., 2000). The bacterial capability of responding to external stimuli is conferred by a specialized signal transduction mechanism, which relies on the two-component systems (TCSs) (Cheung and Hendrickson, 2010; Groisman, 2016). In general, a TCS comprises a sensor protein (histidine kinase or HK) and its corresponding response regulator (RR). Usually, as each particular TCS is specialized to respond to a specific environmental signal (e.g., pH, nutrient levels, osmotic pressure, redox state, quorum-sensing proteins and antibiotics), multiple TCSs may be present in a single bacterial cell.

The virulence factors of bacterial pathogens and the regulatory systems that monitor their expression are predominantly attractive for therapeutic intervention. Recently, TCSs have emerged as potential targets for antibacterial drug design for a number of reasons. As a common practice, conventional antibiotics target specific bacterial proteins that perform essential functions in the pathogen; however, a drug that targets TCSs could be highly effective because it impairs upstream regulatory functions related to the pathogen’s physiology instead of affecting only specific downstream functions. Thus, the use of TCSs for drug development provides an alternative strategy for combating microbial infections, including those caused by pathogens resistant to currently available antibiotics (Gotoh et al., 2010). In addition, as the expression of many antibiotic resistance determinants is regulated by TCSs (Poole, 2012), an effective antimicrobial treatment could also be achieved by combining conventional and TCS-directed drugs. Still, selective TCS inhibitors are supposed to have the least toxicity to mammalian cells, since the bacterial signal transduction systems based on the phosphorylation of histidine differ from the serine/threonine and tyrosine phosphorylation signaling systems normally found in higher eukaryotes. Finally, a high degree of structural homology between the catalytic domains of the histidine kinase and the RR in bacteria suggest that multiple TCSs can be inhibited by a single compound, causing reduction in chromosomal resistance emergence (Barrett and Isaacson, 1995; Poole, 2012). As TCS-encoding genes are found in all Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial genomes, a particular polypharmacological TCS inhibitor with the desired therapeutic effect may act comprehensively, in contrast to polypharmacy practice, if able to breach the various cell envelopes (Anand and Chandra, 2014).

In this review, we list several TCSs that are linked to bacterial virulence and antibiotic resistance, pointing out some of their main characteristics and addressing their possible therapeutic uses as drug targets. Furthermore, the present review provides a compilation of TCS-inhibitors that have been identified by different assays of drug discovery.

The Two-Component Systems and Their Involvement in Bacterial Virulence and Antibiotic Resistance

The basic biochemistry of the TCSs is well defined. A typical sensor histidine kinase comprises two domains: a variable N-terminal input domain and a conserved C-terminal domain that interacts with the RR. In turn, the RR contains one conserved N-terminal receiver domain and one variable C-terminal output domain (Nixon et al., 1986; Bijlsma and Groisman, 2003; Bourret and Silversmith, 2010; Cheung and Hendrickson, 2010; Groisman, 2016; Gislason et al., 2017). When stimulated, the sensor protein catalyzes autophosphorylation in a conserved histidine residue by using adenosine triphosphate (ATP). The high-energy phosphoryl group is then moved to a conserved aspartate residue of the RR, potentially changing its capability of targeting DNA sequences (Bijlsma and Groisman, 2003; Cheung and Hendrickson, 2010). This signal transduction pathway has been reported to involve three phosphotransfer reactions and two phosphoprotein intermediates (Stock et al., 2000; Bijlsma and Groisman, 2003).

In recent years, since protein phosphorylation has been discovered to take place in bacterial nitrogen absorption and chemotaxis, a number of techniques have been developed to study Two-component signal transduction systems (Scharf, 2010). The use of these techniques has allowed identification of stimuli-responsive TCSs, such as PhoPQ TCSs. PhoPQ is known to respond to a wide variety of environmental stress signals, including phosphate (Ogura et al., 2001; Pragai and Harwood, 2002), Mg2+ and Ca2+ starvation, pH, antimicrobial peptides and nutritional deprivation (Hall, 1998; Regelmann et al., 2002; Fontan et al., 2004; Miyashiro and Goulian, 2008). However, experimental verifications of stimuli that activate specific TCSs are reported in very few cases. When studying a TCS, a selection of candidate environmental conditions is usually made taking different physical and chemical parameters into consideration, such as changes in pH and osmolarity levels, oxygen pressure, temperature, exposure to ions, etc. (West and Stock, 2001; Varughese, 2002).

It has also been reported that some TCSs present the ability to regulate gene clusters that contribute to cell growth, biofilm formation and virulence in pathogenic bacteria (Eguchi and Utsumi, 2008; Mitrophanov and Groisman, 2008; Gotoh et al., 2010; Schaefers et al., 2017). Nevertheless, in several cases, the role of TCSs in the pathogenicity of bacteria is not well understood and the attenuation of virulence is observed in TCS mutant strains without immediate knowledge of the exact mechanisms involved. Even though there is little explanation about the mechanisms involved in their attenuation, the TCS mutant strains present great potential to be used as live-attenuated vaccines against bacterial infections.

For example, deletion of the genes encoding PhoP in Mycobacterium and Salmonella result in strains has been used as a vaccination strategy. The phoP Salmonella mutants are attenuated and immunogenic for virulence in animal models (VanCott et al., 1998; Link et al., 2006; Martin et al., 2006). Hohmann et al. (1996) demonstrated that the deletion of phoP/phoQ in Salmonella typhi provides a useful strain for immunogenic live-attenuated vaccine against typhoid fever. The association of TCSs with virulence has been studied in various pathogens, but few TCSs have been shown to be important for the coordination of expression of virulence factors. According to Sengupta et al. (2003), the arcA gene of Vibrio cholerae plays an essential role in the expression of virulence factors. The arcA gene was mutated and experimental animal infections revealed that this gene positively controls the expression of toxT. The gene toxT encodes a transcriptional factor that increases the virulence of V. cholerae by activating genes encoding CT and TcpA (Sengupta et al., 2003).

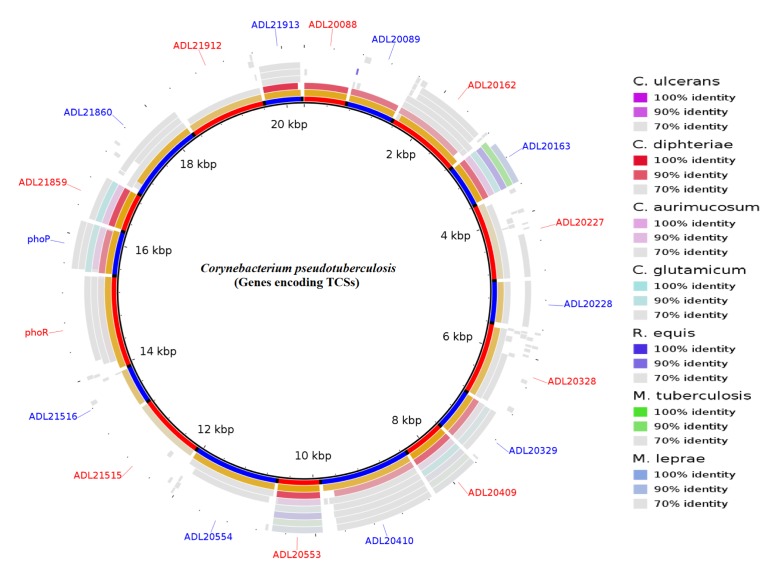

The large number of available bacterial genome sequence databases has made it possible to identify and predict interacting pairs of response regulatory kinases. Among the approaches are the use of tools of Next-generation sequencing (NGS), molecular modeling, and bioinformatics. For example, our group is working with the genomics of pathogenic bacteria. Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis (Cp) is the etiological agent of Caseous Lymphadenitis (CLA), an infectious disease that affects small ruminants worldwide (Dorella et al., 2006; Tiwari et al., 2014). The genome sequence of this bacterium, recently completed, will aid in the identification of homologies and the prediction of novel genes that encode other virulence factors. Genomic sequencing of C. pseudotuberculosis has revealed 10 of these signal transduction systems (Figure 1) (Barakat et al., 2011).

FIGURE 1.

Circular representation of the genes encoding two-component systems (TCSs) in Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis. The figure shows BLAST comparisons with other Actinobacteria.

A number of research groups have recently focused on TCSs to find potent inhibitors. Examples of targeted TCSs are WalKR, which is essential for bacterial survival, QseCB and DosRST, both presenting an important role in virulence and VanSR, which exhibits antibiotic resistance properties. In fact, many envelope transporter proteins acting as efflux pumps to promote the secretion of toxic compounds are controlled by TCSs. It has been reported that the efflux pumps regulated by TCSs in several important human pathogens, including Acinetobacter baumannii and Klebsiella pneumonia, provide multidrug resistance (Howell et al., 2003; Gallego del Sol and Marina, 2013).

In specific, the VanSR TCS is responsible for regulating the genes that confer resistance to vancomycin. It has been reported that Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus faecalis and E. faecium are resistant to vancomycin because of the action of VanSR. Targeting of this TCSs has led to the identification of several potent inhibitors that arrest the energy required for ATP synthesis in the cell (Healy et al., 2000; Pootoolal et al., 2002; Hong et al., 2008; Bem et al., 2015). Due to the negative effect, they exert over the mitochondrial respiration, these inhibitors could not be readily used as drugs. However, they may serve as structural templates for the discovery of novel selective inhibitors to target the VanSR TCS in adjunct therapy.

Recently, in an attempt to modulate the activity of PhoPR TCS in C. pseudotuberculosis, our group evaluated potential binding interactions of prototype molecules from non-synthetic sources with the active site of the PhoP protein (Tiwari et al., 2014). As result, two anthraquinones produced by the plant species Rheum undulatum and R. palmatum, also known as rhein and reported to present antimicrobial activity, have been found to be good candidates to inhibit the activity of the PhoPR TCS in C. pseudotuberculosis.

Some predicted and experimentally validated compounds targeting bacterial TCSs are listed in Table 1. The firstly reported synthetic inhibitors target the Pseudomonas aeruginosa AlgR2/AlgRl TCS, which controls production of the exopolysaccharide alginate, an important virulence factor produced by this bacterium during lung infections (Roychoudhury et al., 1993). The principal approaches applied to the discovery of TCS inhibitors involve high throughput screening assays with purified TCSs and structure-based virtual screening (SBVS) using different types of compound libraries and rational drug design (Qin et al., 2006). By using these techniques, a number of synthetic compounds belonging to several classes, such as benzoxazines, benzimidazoles (Hilliard et al., 1998), bisphenols, cyclohexenes, trityls and salicylanilides (Hlasta et al., 1998), were identified to inhibit the KinA-Spo0F TCS in Bacillus subtilis. Concerning the effects of these compounds over bacterial growth, the 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50s) ranged from 1.9 to 0.5 mM and the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) ranged from 0.5 to 0.16 mg/ml for some bacteria (Hilliard et al., 1999; Stephenson and Hoch, 2002).

Table 1.

Two-component systems targeted by molecular compounds with antibacterial activity.

| Bacteria | Inhibitors | Two component system | Component of TCS studied | Mechanism of action | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Thiazole derivatives | Algr1/Algr2 | Sensor protein | Inhibition of phosphorylation/dephosphorylation of Algr2 | Roychoudhury et al., 1993 |

| Enterococcus faecium | Thiazole derivatives | VanR/VanS | Sensor protein | Inhibition of autophosphorylation | Ulijasz and Weisblum, 1999 |

| Bacillus subtilis | Walkmycin B and Waldiomycin | WalK/WalR | Sensor protein | Binds to the HK cytoplasmic domain for the inhibition of autophosphorylation | Okada et al., 2010 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Walkmycin B and Waldiomycin | WalK/WalR | Sensor protein | Binds to the HK cytoplasmic domain for the inhibition of autophosphorylation | Okada et al., 2010 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Salicylanilide | KinA/Spo0F | Sensor protein | Affects membrane fluidity, disturbing signal transduction | Hilliard et al., 1999 |

| Bacillus subtilis | Unsaturated fatty acids | KinA | Sensor protein | Causes non-competitive inhibition of ATP-dependent autophosphorylation | Barrett and Hoch, 1998 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Thiazole derivatives | Algr1/Algr2 | Response regulator | Inhibition of DNA-binding activity of Algr1 | Roychoudhury et al., 1993 |

| Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis | Rhein | PhoP/PhoR | Response regulator | Inhibition of conserved receiver domain of PhoP | Tiwari et al., 2014 |

| Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus | Bis-phenol | VanR/VanS | Response regulator | – | Barrett and Hoch, 1998 |

| Salmonella enterica | NSC9608 (8 compounds, NCI library) | PhoP/PhoQ | Response regulator | Inhibition of formation of the PhoP-DNA complex | Tang et al., 2012 |

Identification of Specific Inhibitors Against TCSs in Different Bacteria

Presently, several factors contribute to the urgent need for innovative therapeutics: (i) the rise of anti-microbial resistance in pathogenic bacterial strains worldwide, (ii) prolonged therapy, (iii) co-morbidity with immunosuppressive diseases like HIV, pooled with a rapid rate of microbial evolution, (iv) the bacterial latency caused when bacteria enter and reside in a dormant state even for several decades and (v) a slower development of new antibiotics. The world’s scientific community is facing a post-antibiotic era with a small number of available vaccines and a handful of chemotherapeutic agents available to battle infectious diseases (Worthington et al., 2013). In this regard, further basic research combined with modern drug discovery technologies may aid in the understanding of bacterial pathogenesis and cellular signaling pathways, leading to the development of novel therapeutic applications to exterminate bacterial infections.

Recognition of the relationship between TCSs and promotion of virulence in bacterial pathogens has directed the pharmaceutical industry to largely invest in the search of suitable inhibitors aiming signal transduction in bacteria. The catalytic and receiver domains of HKs and RRs are well studied and share a high degree of structural homology (Barrett and Hoch, 1998; Domagala et al., 1998). This knowledge suggests that a single drug compound capable of targeting any of these conserved domains could simultaneously inhibit multiple TCSs, boosting the chances to develop confrontation against the effects caused by the emergence of any molecular mutations affecting the affinity of the drug ligand for the target protein (Okada et al., 2007; Worthington et al., 2013). In this regard, targeting multiple TCSs through their conserved domains may be more effective than targeting the varying sensor domain of each HK (Gotoh et al., 2010; Bem et al., 2015). On the other hand, sequence conservation in kinase domains among bacteria and eukaryotes consists a possible disadvantage of targeting HKs. The ATP-binding pocket (Bergerat fold) present in bacterial HKs exhibits a high homology level with several human protein families and is also present in essential proteins found in a broad range of organisms, including the chaperone Hsp90 (Bem et al., 2015).

Computational programs relying on structure-activity relationship (SAR) have been used in medicinal chemistry studies aiming to identify compounds capable of inhibiting TCSs in pathogenic bacteria (Domagala et al., 1998; Weidner-Wells et al., 2001). Studies depicting the mechanisms of action of such compounds have revealed that some of the most promising TCS inhibitors – namely, the salicylanilides, trityl compounds and benzimidazoles – cause substantial hemolysis of equine erythrocytes, affect integrity of the cellular membrane in S. aureus and have a damaging effect on the synthesis of macromolecules (Hilliard et al., 1999; Stephenson and Hoch, 2002).

A number of halogenated pyrrolo [2, 1-b] [1, 3] benzoxazines (streptopyrroles) isolated from fermentations of Streptomyces rimosus have been shown to possess antimicrobial activity against a series of bacteria and fungi (Trew et al., 2000). The most promising streptopyrrole candidate presented inhibition against drug-resistant S. aureus strains at the MIC of 0.2 mg/mL. This candidate compound has also been able to repress auto-phosphorylation of the Escherichia coli NRII sensor kinase, providing an IC50 of 20 mM. (Stephenson and Hoch, 2002). However, similarities between the structures of streptopyrroles and salicylanilides suggest that the inhibition caused by these compounds may be a result of non-specific effects such as self-aggregation.

There are several methods to enhance the discovery/design of drugs targeting TCSs. First, the SBVS analysis should be performed using compound databases comprehending a wide variety of potential inhibitors, including structures reported to present antibacterial activity (Payne et al., 2007; Bem et al., 2015). Second, information about targeted TCSs should be obtained from clinically important pathogens to facilitate the identification of effective specific inhibitors. Third, the modeling refinement of TCS protein structures may facilitate the search for compounds using the SBVS approach by allowing a more precise molecular docking analysis. The structural information obtained from these proteins can also help to identify the binding sites and chemical spaces that allow the interaction with candidate compounds, leading to further refinement in the prediction of novel inhibitors. In this regard, structural data of proteins that have been co-crystalized with ligand molecules are of special interest. Finally, the generation of additional structure-activity relationship data will aid to minimize toxicity of the TCS inhibitors in eukaryotic cells and improve our understanding on the mechanisms of action of these compounds.

Conclusion

The bacterial TCS consists of an important signaling mechanism for survival and establishment of pathogenic bacteria within the host. Along with the current need for new antimicrobial drugs, the regulatory nature of TCSs makes these systems outstanding targets for the development of alternative therapeutics against bacterial infections. Their broad prevalence and the functional diversity of TCSs also support the need for testing several compounds against TCSs. Although the structural conservation of domains present in histidine kinases and sensor proteins may facilitate the prediction of inhibitors, a substantial extent of similarity between bacterial TCSs and other eukaryotic related proteins provide important concerns in relation to the effectiveness of TCS-directed drugs, which could affect cellular processes in the host’s organism. In this regard, a better understanding of the interaction between a TCS and its targeting compound may aid in the development of an improved molecular structure presenting increased specificity for the correct ligand. Several works have reported natural and synthetic compounds presenting high affinity for TCSs and antimicrobial activity over pathogenic bacteria, but more studies are necessary to understand the exact mechanisms of action of these drugs.

Author Contributions

ST, SBJ, and PVSDC wrote the paper. SSH, SA, AS, DB, TLPC, PG, and VA guided and reviewed the work.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the collaboration and assistance of all team members and the brazilian funding agencies CAPES, CNPq and FAPEMIG. ST and SBJ acknowledge the receipt of fellowship under “TWAS-CNPq Postgraduate Fellowship Programme” for doctoral studies; DB acknowledges the “TWAS-CNPq Postdoctoral Fellowship Programme” for granting a fellowship for postdoctoral studies and UFMG.

References

- Anand P., Chandra N. (2014). Characterizing the pocketome of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and application in rationalizing polypharmacological target selection. Sci. Rep. 4:6356. 10.1038/srep06356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barakat M., Ortet P., Whitworth D. E. (2011). P2CS: a database of prokaryotic two-component systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 39 D771–D776. 10.1093/nar/gkq1023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett J. F., Hoch J. A. (1998). Two-component signal transduction as a target for microbial anti-infective therapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42 1529–1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett J. F., Isaacson R. E. (1995). Chapter 12. Bacterial virulence as a potential target for therapeutic intervention. Annu. Rep. Med. Chem. 30 111–118. 10.1016/s0065-7743(08)60925-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bem A. E., Velikova N., Pellicer M. T., Baarlen P., Marina A., Wells J. M. (2015). Bacterial histidine kinases as novel antibacterial drug targets. ACS Chem. Biol. 10 213–224. 10.1021/cb5007135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bijlsma J. J., Groisman E. A. (2003). Making informed decisions: regulatory interactions between two-component systems. Trends Microbiol. 11 359–366. 10.1016/S0966-842X(03)00176-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourret R. B., Silversmith R. E. (2010). Two-component signal transduction. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 13 113–115. 10.1016/j.mib.2010.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung J., Hendrickson W. A. (2010). Sensor domains of two-component regulatory systems. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 13 116–123. 10.1016/j.mib.2010.01.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domagala J. M., Alessi D., Cummings M., Gracheck S., Huang L., Huband M., et al. (1998). Bacterial two-component signalling as a therapeutic target in drug design. Inhibition of NRII by the diphenolic methanes (bisphenols). Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 456 269–286. 10.1007/978-1-4615-4897-3_14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorella F. A., Pacheco L. G., Oliveira S. C., Miyoshi A., Azevedo V. (2006). Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis: microbiology, biochemical properties, pathogenesis and molecular studies of virulence. Vet. Res. 37 201–218. 10.1051/vetres:2005056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eguchi Y., Utsumi R. (2008). Introduction to bacterial signal transduction networks. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 631 1–6. 10.1007/978-0-387-78885-2_1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontan P. A., Walters S., Smith I. (2004). Cellular signaling pathways and transcriptional regulation in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: stress control and virulence. Curr. Sci. 86 122–134. 10.1074/jbc.M112.448217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallego del Sol F., Marina A. (2013). Structural basis of Rap phosphatase inhibition by Phr peptides. PLOS Biol. 11:e1001511. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gislason A. S., Choy M., Bloodworth R. A., Qu W., Stietz M. S., Li X., et al. (2017). Competitive growth enhances conditional growth mutant sensitivity to antibiotics and exposes a two-component system as an emerging antibacterial target in Burkholderia cenocepacia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 61 e790–e716. 10.1128/AAC.00790-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotoh Y., Eguchi Y., Watanabe T., Okamoto S., Doi A., Utsumi R. (2010). Two-component signal transduction as potential drug targets in pathogenic bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 13 232–239. 10.1016/j.mib.2010.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groisman E. A. (2016). Feedback control of two-component regulatory systems. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 70 103–124. 10.1146/annurev-micro-102215-095331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall B. G. (1998). Adaptive mutagenesis at ebgR is regulated by PhoPQ. J. Bacteriol. 180 2862–2865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healy V. L., Lessard I. A., Roper D. I., Knox J. R., Walsh C. T. (2000). Vancomycin resistance in enterococci: reprogramming of the D-ala-D-Ala ligases in bacterial peptidoglycan biosynthesis. Chem. Biol. 7 R109–R119. 10.1016/S1074-5521(00)00116-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilliard J. J., Goldschmidt R. M., Licata L., Baum E. Z., Bush K. (1999). Multiple mechanisms of action for inhibitors of histidine protein kinases from bacterial two-component systems. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43 1693–1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilliard J. J., Licata L., Goldschmidt R., Baum E. Z., Macielag M., Hlasta D. J., et al. (1998). “Multiple mechanisms of action for inhibitors of histidine protein kinase from bacterial two-component systems,” in Proceedings of the in Abstracts of the 38th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy (Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology; ). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hlasta D. J., Demers J. P., Foleno B. D., Fraga-Spano S. A., Guan J., Hilliard J. J., et al. (1998). Novel inhibitors of bacterial two-component systems with gram positive antibacterial activity: pharmacophore identification based on the screening hit closantel. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 8 1923–1928. 10.1016/S0960-894X(98)00326-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoch J. A. (2000). Two-component and phosphorelay signal transduction. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 3 165–170. 10.1016/S1369-5274(00)00070-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohmann E. L., Oletta C. A., Miller S. I. (1996). Evaluation of a phoP/phoQ-deleted, aroA-deleted live oral Salmonella typhi vaccine strain in human volunteers. Vaccine 14 19–24. 10.1016/0264-410X(95)00173-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong H. J., Hutchings M. I., Buttner M. J., Biotechnology, and Biological Sciences Research Council U. K. (2008). Vancomycin resistance VanS/VanR two-component systems. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 631 200–213. 10.1007/978-0-387-78885-2_14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell A., Dubrac S., Andersen K. K., Noone D., Fert J., Msadek T., et al. (2003). Genes controlled by the essential YycG/YycF two-component system of Bacillus subtilis revealed through a novel hybrid regulator approach. Mol. Microbiol. 49 1639–1655. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03661.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link C., Ebensen T., Standner L., Dejosez M., Reinhard E., Rharbaoui F., et al. (2006). An SopB-mediated immune escape mechanism of Salmonella enterica can be subverted to optimize the performance of live attenuated vaccine carrier strains. Microbes Infect. 8 2262–2269. 10.1016/j.micinf.2006.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin C., Williams A., Hernandez-Pando R., Cardona P. J., Gormley E., Bordat Y., et al. (2006). The live Mycobacterium tuberculosis phoP mutant strain is more attenuated than BCG and confers protective immunity against tuberculosis in mice and guinea pigs. Vaccine 24 3408–3419. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitrophanov A. Y., Groisman E. A. (2008). Signal integration in bacterial two-component regulatory systems. Genes Dev. 22 2601–2611. 10.1101/gad.1700308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyashiro T., Goulian M. (2008). High stimulus unmasks positive feedback in an autoregulated bacterial signaling circuit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 17457–17462. 10.1073/pnas.0807278105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon B. T., Ronson C. W., Ausubel F. M. (1986). Two-component regulatory systems responsive to environmental stimuli share strongly conserved domains with the nitrogen assimilation regulatory genes ntrB and ntrC. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 83 7850–7854. 10.1073/pnas.83.20.7850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogura M., Yamaguchi H., Yoshida K., Fujita Y., Tanaka T. (2001). DNA microarray analysis of Bacillus subtilis DegU, ComA and PhoP regulons: an approach to comprehensive analysis of B. subtilis two-component regulatory systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 29 3804–3813. 10.1093/nar/29.18.3804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada A., Gotoh Y., Watanabe T., Furuta E., Yamamoto K., Utsumi R. (2007). Targeting two-component signal transduction: a novel drug discovery system. Methods Enzymol. 422 386–395. 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)22019-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada A., Igarashi M., Okajima T., Kinoshita N., Umekita M., Sawa R., et al. (2010). Walkmycin B targets WalK (YycG), a histidine kinase essential for bacterial cell growth. J. Antibiot. 63 89–94. 10.1038/ja.2009.128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne D. J., Gwynn M. N., Holmes D. J., Pompliano D. L. (2007). Drugs for bad bugs: confronting the challenges of antibacterial discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 6 29–40. 10.1038/nrd2201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole K. (2012). Bacterial stress responses as determinants of antimicrobial resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67 2069–2089. 10.1093/jac/dks196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pootoolal J., Neu J., Wright G. D. (2002). Glycopeptide antibiotic resistance. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 42 381–408. 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.42.091601.142813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pragai Z., Harwood C. R. (2002). Regulatory interactions between the Pho and sigma(B)-dependent general stress regulons of Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology 148(Pt 5) 1593–1602. 10.1099/00221287-148-5-1593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Z., Zhang J., Xu B., Chen L., Wu Y., Yang X., et al. (2006). Structure-based discovery of inhibitors of the YycG histidine kinase: new chemical leads to combat Staphylococcus epidermidis infections. BMC Microbiol. 6:96. 10.1186/1471-2180-6-96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regelmann A. G., Lesley J. A., Mott C., Stokes L., Waldburger C. D. (2002). Mutational analysis of the Escherichia coli PhoQ sensor kinase: differences with the Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium PhoQ protein and in the mechanism of Mg2+ and Ca2+ sensing. J. Bacteriol. 184 5468–5478. 10.1128/JB.184.19.5468-5478.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roychoudhury S., Zielinski N. A., Ninfa A. J., Allen N. E., Jungheim L. N., Nicas T. I., et al. (1993). Inhibitors of two-component signal transduction systems: inhibition of alginate gene activation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90 965–969. 10.1073/pnas.90.3.965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefers M. M., Liao T. L., Boisvert N. M., Roux D., Yoder-Himes D., Priebe G. P. (2017). An oxygen-sensing two-component system in the Burkholderia cepacia complex regulates biofilm, intracellular invasion, and pathogenicity. PLOS Pathog. 13:e1006116. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharf B. E. (2010). Summary of useful methods for two-component system research. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 13 246–252. 10.1016/j.mib.2010.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta N., Paul K., Chowdhury R. (2003). The global regulator ArcA modulates expression of virulence factors in Vibrio cholerae. Infect. Immun. 71 5583–5589. 10.1128/IAI.71.10.5583-5589.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson K., Hoch J. A. (2002). Virulence- and antibiotic resistance-associated two-component signal transduction systems of Gram-positive pathogenic bacteria as targets for antimicrobial therapy. Pharmacol. Ther. 93 293–305. 10.1016/S0163-7258(02)00198-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stock A. M., Robinson V. L., Goudreau P. N. (2000). Two-component signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69 183–215. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y. T., Gao R., Havranek J. J., Groisman E. A., Stock A. M., Marshall G. R. (2012). Inhibition of bacterial virulence: drug-like molecules targeting the Salmonella enterica PhoP response regulator. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 79 1007–1017. 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2012.01362.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari S., da Costa M. P., Almeida S., Hassan S. S., Jamal S. B., Oliveira A., et al. (2014). C. pseudotuberculosis Phop confers virulence and may be targeted by natural compounds. Integr. Biol. 6 1088–1099. 10.1039/c4ib00140k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trew S. J., Wrigley S. K., Pairet L., Sohal J., Shanu-Wilson P., Hayes M. A., et al. (2000). Novel streptopyrroles from Streptomyces rimosus with bacterial protein histidine kinase inhibitory and antimicrobial activities. J. Antibiot. 53 1–11. 10.7164/antibiotics.53.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulijasz A. T., Weisblum B. (1999). Dissecting the VanRS signal transduction pathway with specific inhibitors. J. Bacteriol. 181 627–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanCott J. L., Chatfield S. N., Roberts M., Hone D. M., Hohmann E. L., Pascual D. W., et al. (1998). Regulation of host immune responses by modification of Salmonella virulence genes. Nat. Med. 4 1247–1252. 10.1038/3227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varughese K. I. (2002). Molecular recognition of bacterial phosphorelay proteins. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 5 142–148. 10.1016/S1369-5274(02)00305-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidner-Wells M. A., Ohemeng K. A., Nguyen V. N., Fraga-Spano S., Macielag M. J., Werblood H. M., et al. (2001). Amidino benzimidazole inhibitors of bacterial two-component systems. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 11 1545–1548. 10.1016/S0960-894X(01)00024-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West A. H., Stock A. M. (2001). Histidine kinases and response regulator proteins in two-component signaling systems. Trends Biochem. Sci. 26 369–376. 10.1016/S0968-0004(01)01852-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worthington R. J., Blackledge M. S., Melander C. (2013). Small-molecule inhibition of bacterial two-component systems to combat antibiotic resistance and virulence. Future Med. Chem. 5 1265–1284. 10.4155/fmc.13.58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]