Abstract

Background and Aims

Recent clinical trials and in vivo models demonstrate probiotic administration can reduce occurrence and improve outcome of pneumonia and sepsis, both major clinical challenges worldwide. Potential probiotic benefits include maintenance of gut epithelial barrier homeostasis and prevention of downstream organ dysfunction due to systemic inflammation. However, mechanism(s) of probiotic-mediated protection against pneumonia remain poorly understood. This study evaluated potential mechanistic targets in the maintenance of gut barrier homeostasis following Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG) treatment in a mouse model of pneumonia.

Methods

Studies were performed in 6–8 week old FVB/N mice treated (o.g.) with or without LGG (109CFU/ml) and intratracheally injected with Pseudomonas aeruginosa or saline. At 4, 12, and 24h post-bacterial treatment spleen and colonic tissue were collected for analysis.

Results

Pneumonia significantly increased intestinal permeability and gut claudin-2. LGG significantly attenuated increased gut permeability and claudin-2 following pneumonia back to sham control levels. As mucin expression is key to gut barrier homeostasis we demonstrate that LGG can enhance goblet cell expression and mucin barrier formation versus control pneumonia animals. Further as Muc2 is a key gut mucin, we show LGG corrected deficient Muc2 expression post-pneumonia. Apoptosis increased in both colon and spleen post-pneumonia, and this increase was significantly attenuated by LGG. Concomitantly, LGG corrected pneumonia-mediated loss of cell proliferation in colon and significantly enhanced cell proliferation in spleen. Finally, LGG significantly reduced pro-inflammatory cytokine gene expression in colon and spleen post-pneumonia.

Conclusions

These data demonstrate LGG can maintain intestinal barrier homeostasis by enhancing gut mucin expression/barrier formation, reducing apoptosis, and improving cell proliferation. This was accompanied by reduced pro-inflammatory cytokine expression in the gut and in a downstream organ (spleen). These may serve as potential mechanistic targets to explain LGG’s protection against pneumonia in the clinical and in vivo setting.

Keywords: Probiotics, Mucin, Mouse, Apoptosis, Gut Barrier

INTRODUCTION

Infection and pneumonia remain a major cause of morbidity and mortality despite advances in supportive care and antimicrobial therapy (1). Recently, a multi-national intensive care unit (ICU) survey of over 14,000 patients in more then 1200 ICUs found 51% of patients were considered infected on the day of the survey and 71% were receiving antibiotics. In this study, 64% percent of infections were of respiratory origin and the hospital mortality rate of infected patients was greater than double that of uninfected patients (33% vs. 15%)(1). Furthermore, antibiotics used to treat these infections lead to loss of commensal gastrointestinal (GI) microbiota and potentially to overgrowth of pathogens (dysbiosis) that may also be resistant to standard antimicrobial agents (2, 3). The intestine is thought to be the “motor” of systemic inflammatory response syndrome regardless of the location of the initial infection (4). The effect of alterations in the gut microbiota and gut barrier homeostasis are thought to be transmitted to and propagated by downstream organs, such as the spleen where large immune cell populations are harbored (5). Alterations in intestinal homeostasis and gut microbiota in sepsis results in increased inflammatory cytokine production (6), gut barrier dysfunction (7), and increased cellular apoptosis (8) all of which may contribute to multiple organ failure (MOF).

A promising intervention to maintain gut integrity and prevent pathologic alterations in the gut microbiota or “dysbiosis” is the use of probiotic bacteria (9). Probiotic use in ICU has recently been supported by several clinical trials and meta-analysis work (10–12) showing significant reduction of infections, and specifically ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) (13). Although probiotics show promise as effective treatments in a range of clinical conditions, the specific mechanisms of benefit are complex and not fully described (14). Based on the results from in vivo and in vitro studies in other models, it appears that probiotics may reduce intestinal epithelial cell apoptosis (15), improve intestinal integrity (16), and prevent bacterial translocation (17), reduce overgrowth of pathogenic bacteria, and potentially suppress inflammatory cytokine production (18, 19).

As stated, some of the most promising data for probiotic use is in prevention and improved outcome from pneumonia in clinical critical care as well as in vivo pneumonia models (10, 20). Interestingly, recent meta-analysis data indicates that the clinical benefit of probiotics on pneumonia may be most significant in prevention of pneumonia from P. aeruginosa (11). In support of this, our laboratory has also recently shown that Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG) (a commonly used clinical probiotic) can reduce mortality and bacteremia from experimental P. aeruginosa pneumonia (21). However, as stated, the mechanisms of probiotic-mediated protection against pneumonia, and sepsis in general, are poorly understood. Given this data, and given that P. aeruginosa pneumonia is one of the most common gram-negative bacteria causing pneumonia in critically ill patients with a high fatality rate (22) we chose to further investigate potential mechanistic targets of LGG in improving outcome from experimental P. aeruginosa pneumonia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Probiotic treatment and pneumonia model

All animal protocols utilized in this study were reviewed and approved by the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.. The pneumonia model utilized 6–8 week old FVB/N mice receiving a single dose of LGG. Specifically mice were orally gavaged with 200 µl of either LGG (1×109 colony forming unit (CFU)/ml)) or sterile water (vehicle) immediately prior to procedure. Pneumonia was initiated via direct intratracheal instillation of P. aeruginosa as previously described (21). All mice were then treated with antibiotics (gentamicin 0.2mg/ml, subcutaneously) following surgery to mimic the clinical setting. Animals were euthanized at 4, 12 or 24 hours. To provide standardization throughout manuscript, control animals not receiving probiotics are referred to as “control pneumonia animals” or “pneumonia alone”.

Bacterial culture

P. aeruginosa 27853 (ATCC, Manassas, VA) was incubated in Tripticase soy broth (BD, Sparks, MD) for 24 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2. LGG (ATCC, Manassas, VA) was incubated in de Man, Rogosa and Sharpe broth (BD, Sparks, MD) for 24 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2. A600 was measured to determine the number of CFU per 1ml. P. aeruginosa and LGG were pelleted from the broth (10,000rpm; 10min) and resuspended in sterile saline or distilled water respectively.

Intestinal permeability

Mice were gavaged with 0.5ml of 22mg/ml fluorescein isothiocyanate dextran (FD4) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in sterile phosphate-buffered saline 24h after P. aeruginosa inoculation. Plasma was collected 5h later and the concentration of FD4 was measured by fluorospectrometry (BioTek, Winooski, VT).

RNA Preparation, RT, and Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from colon and spleen tissue (snap frozen in liquid N2, collected at 12h) as described (21). RNA concentrations were quantified at 260 nm, and the purity and integrity were determined using a NanoDrop. Reverse transcription and real-time PCR assays were performed to quantify steady-state messenger RNA levels of TNF-α, IL1b, IL-6, Muc-2, and claudin-2 as described previously (21).

Immunostaining of mucins, Muc-2 and Claudin-2

Colonic tissue was collected from each animal at 24h and fixed overnight in 10% formalin, paraffin-embedded, and sectioned at 4–6 µm.

Mucins: after deparaffinization and rehydration, sections were Alcian Blue – PAS stained according to manufacturer’s protocol (IHCWorld, LLC Woodstock, MD). Strongly acidic mucins are stained blue, neutral mucins magenta and mixtures of both purple. The nuclei is stained deep blue.

Muc-2: serial sections were blocked with 1.5% rabbit or goat serum (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) in PBS for 30 min, then incubated with rabbit polyclonal Muc-2 (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) antibody for 1 hour, washed with PBS, and incubated with goat anti-rabbit biotinylated secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories) for 30 min. Vectastain Elite ABC reagent (Vector Laboratories) was then applied, followed by diaminobenzidine (DAB) as substrate. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated and cover-slipped.

Claudin-2: after deparaffinization and rehydration, sections were blocked in 5% BSA to prevent nonspecific staining and incubated with mouse monoclonal anti-claudin-2 (Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA) followed by incubation with Alexa-488 conjugated donkey anti-mouse secondary antibody (Invitrogen) and mounted with ProLong Gold antifadereagent containing DAPI as a nuclear counterstain (Invitrogen). Negative control sections were treated with the same procedure in the absence of primary antibody; no immunostaining was observed in the controls (not shown). Images were taken with Olympus BX51.

Western Blot

Colonic tissue was harvested and frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen. Western Blotting was performed as previosuly described (21). Mouse primary antibodies against Claudin-2 (1:250), (Invitrogen) or b-actin (1:10,000) (Sigma) were uilized in western blotting experiments.

Apoptosis and proliferation

Spleen and colon tissue were collected from each animal at 12h and fixed overnight in 10% formalin, paraffin-embedded, and sectioned at 4–6 µm. Serial sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) and evaluated for morphologic changes characteristic of apoptosis such as nuclear fragmentation and cell shrinkage with condensed nuclei (23). To determine apoptosis in the colonic epithelium and spleen, apoptotic epithelial cells were quantified in 100 consecutive crypts (in colon) or ten random high-power fields per section (spleen).

Cleaved caspase 3 (CC3) and proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) staining: after deparaffinization and rehydration, sections were blocked with 1.5% rabbit or goat serum (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) in PBS for 30 min, then incubated with either rabbit polyclonal CC3 (1:100; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) or mouse monoclonal PCNA (1:100; Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA) antibody for 1 hour, washed with PBS, and incubated with either goat anti-rabbit or anti-mouse biotinylated secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories) for 30 min. Vectastain Elite ABC reagent (Vector Laboratories) was then applied, followed by diaminobenzidine (DAB) as substrate. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated and cover-slipped. CC3 positive cells were quantified in 100 consecutive crypts (in colon) or ten random high-power fields per section (spleen). Colonic epithelial proliferation and proliferation in spleen was determined by quantifying PCNA-positive cells in 100 consecutive crypts or ten random high-power fields per section (spleen). All counting was performed by a blinded evaluator.

Statistics

Comparisons were performed with t test analysis (unpaired, two-tailed). Data were analyzed using Prism 4.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) and reported as means ± SE. A P value ≤ 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

LGG treatment significantly improves intestinal permeability and normalizes Claudin-2 expression following P. aeruginosa pneumonia

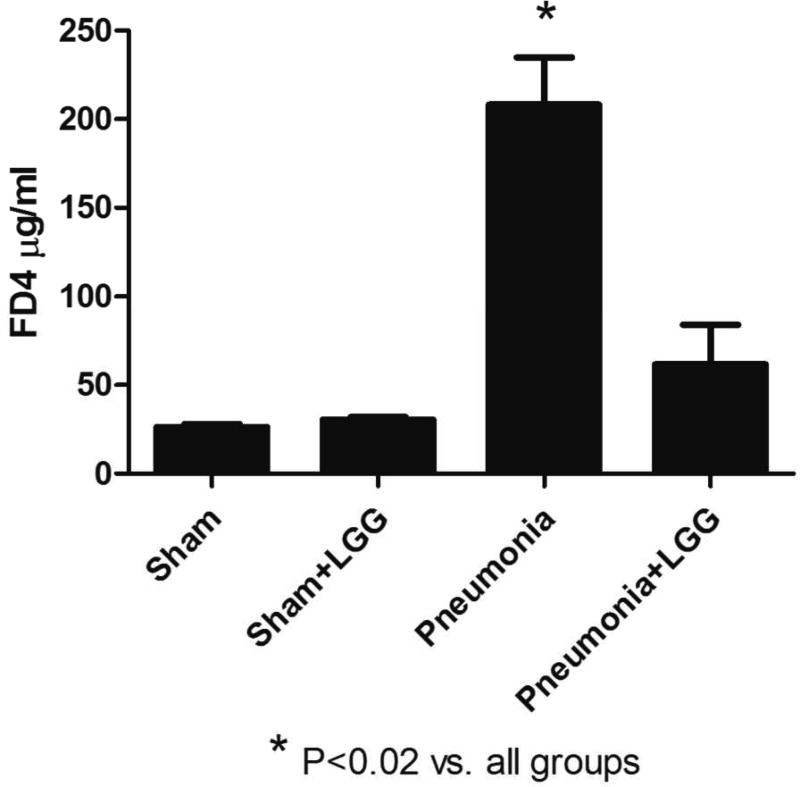

P. aeruginosa infection results in increased intestinal permeability as previously shown (24). To determine whether treatment with LGG can improve this condition, animals were gavaged with FD4 24h post-pneumonia and fluorescence was measured in plasma 5 hours later. Indeed, intestinal permeability was significantly increased in P. aeruginosa infected mice (P<0.02) compared to shams. Interestingly, LGG administration significantly improved (P<0.02) intestinal permeability of mice following pneumonia comparable to baseline permeability seen in sham mice (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Effect of LGG treatment on intestinal permeability.

Plasma levels of FD4 at 24h were significantly higher in pneumonia mice compared to shams (P<0.02) and treatment with LGG reduced these levels significantly (P<0.02). Shams n=3 per group; Pneumonia, Pneumonia+LGG n=4–5 per group. Data are expressed as the mean ± SE.

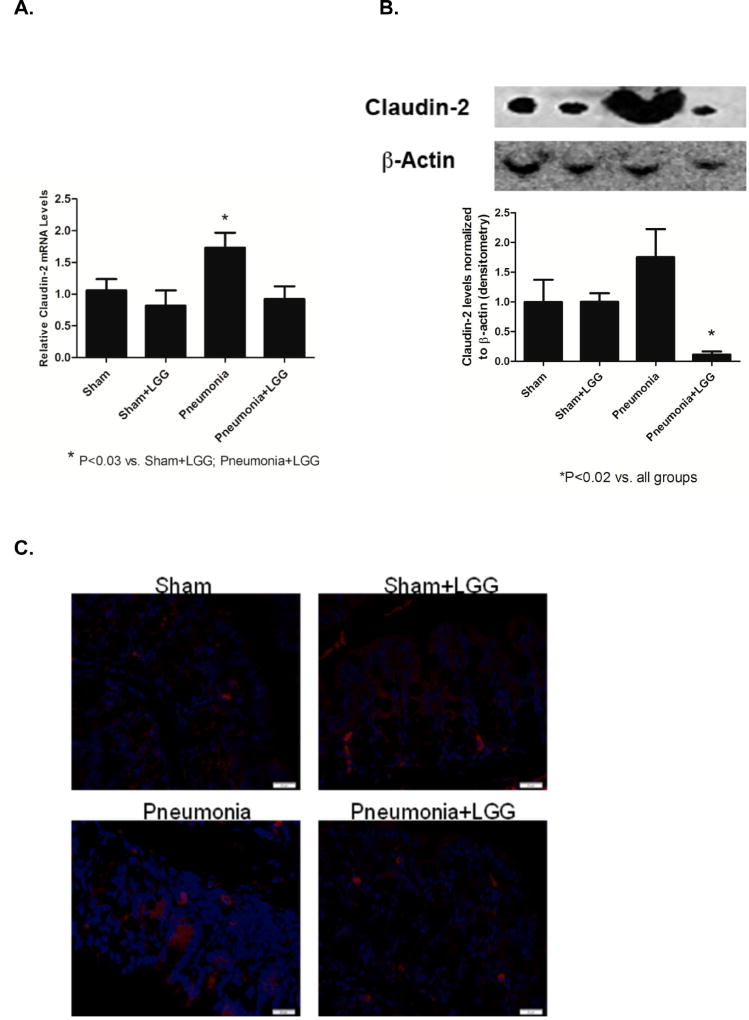

Tight junction proteins play an important role in intestinal integrity. Claudin-2 is considered to be the “leaky” protein and its higher expression is linked to increased intestinal permeability (25). To evaluate the effect of LGG treatment on claudin-2 expression in P. aeruginosa induced pneumonia, we analyzed colonic samples at 24h following pneumonia. mRNA levels were significantly higher in the pneumonia group (P<0.03) and significantly reduced in LGG treated group (P<0.03) (Figure 2A). Protein analysis also showed a significant increase of claudin-2 in the colons of mice following pneumonia (P<0.02) when compared to shams. This increased claudin-2 expression was significantly attenuated (P<0.02) in colons of pneumonia mice treated with LGG (Figure 2B). The localization of Claudin-2 in the colon of mice with pneumonia was largely in the lower part of the crypt, dispersed in the cytoplasm and with higher intensity in comparison to the shams or LGG-treated mice with pneumonia (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. Effect of LGG treatment on Claudin-2 expression and localization in the colon.

(A) Reverse transcription and real-time PCR assays were performed to quantify steady-state mRNA level of Claudin-2 in the colon at 24h. Pneumonia group expressed significantly higher levels of Claudin-2 when compared to shams and LGG treated pneumonia group (P<0.03). Shams n=3–4 per group; Pneumonia, Pneumonia+LGG n=5 per group. Data are expressed as the mean ± SE. (B) Protein levels of Claudin-2 at 24h analyzed by Western blot were significantly higher in colon of pneumonia mice (P<0.02) when compared to shams and pneumonia mice treated with LGG. Representative bands for all groups are shown. Shams n=3–4 per group; Pneumonia, Pneumonia+LGG n=5 per group. Data are expressed as the mean ± SE. (C) The localization of Claudin-2 at 24h in colon of pneumonia mice was mostly in the lower part of the crypt, dispersed in the cytoplasm and with higher intensity in comparison to the shams or pneumonia mice treated with LGG.

LGG improves mucin production and Muc2 expression following P. aeruginosa pneumonia

Probiotics are thought to increase mucin production in the intestine (26). To determine if the improved intestinal permeability may be related to increased mucin production, we used Alcian Blue-PAS and Muc-2 staining in colonic tissue sections (at 24h timepoint). A mixture of neutral and acidic mucins was found in goblet cells of the colon in all experimental groups. However in mice following pneumonia, the mucins were predominantly located inside the goblet cells of the crypts. In contrast, in LGG-treated mice post-pneumonia mucins were secreted to create a protective mucus layer, as observed in sham mice (Figure 3A).

Figure 3. Effect of LGG treatment on mucin expression in the colon.

(A) Alcian blue – PAS stained colonic sections (24h time point). Strongly acidic mucins are stained blue, neutral mucins magenta and mixtures of both purple. The nuclei is stained deep blue. A mixture of neutral and acidic mucins was found in goblet cells in all experimental groups. In pneumonia mice however, the mucins are predominantly located inside the goblet cells of the crypts and in contrast secreted to create a protective mucus layer in pneumonia mice treated with LGG or shams. (B) Higher frequency of Muc-2 producing goblet cells was located in the intestinal epithelium at 24h of the mice treated with LGG and in shams than in colons of mice with pneumonia. (C) Gene expression of Muc-2 at 12h was significantly lower in colon of pneumonia mice (P<0.05) compared to shams and normalized in LGG treated group (P<0.05). Shams n=4 per group; Pneumonia, Pneumonia+LGG n=6–8 per group. Data are expressed as the mean ± SE.

Similarly, a higher frequency of Muc-2 producing goblet cells were observed in the intestinal epithelium of mice treated with LGG and in shams versus in the colons of mice with pneumonia (not LGG treated) at 24h (Figure 3B). Expression of Muc-2 mRNA in the colon (at 12h timepoint) was significantly lower in the mice with P. aeruginosa induced pneumonia and normalized to levels seen in shams in mice receiving LGG treatment (P<0.05) (Figure 3C).

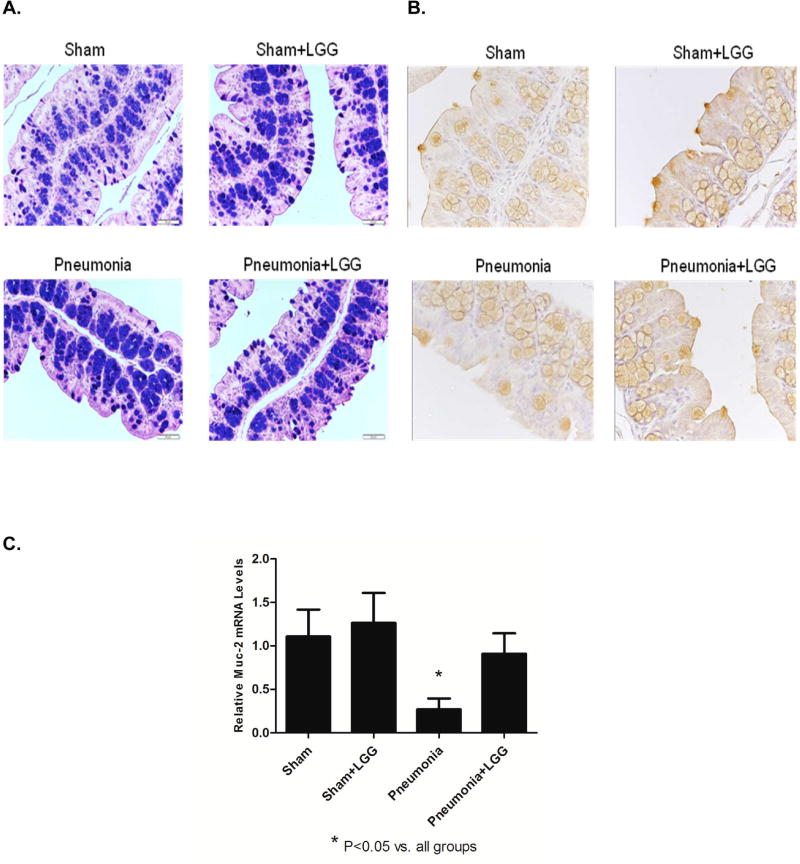

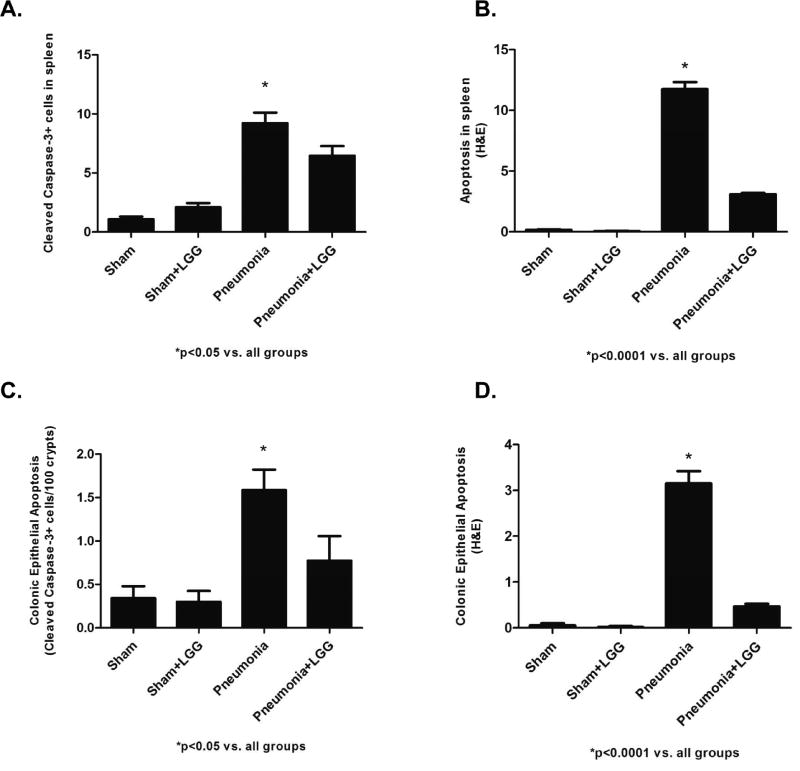

LGG reduces apoptosis and improves proliferation in colon and spleen following P. aeruginosa pneumonia

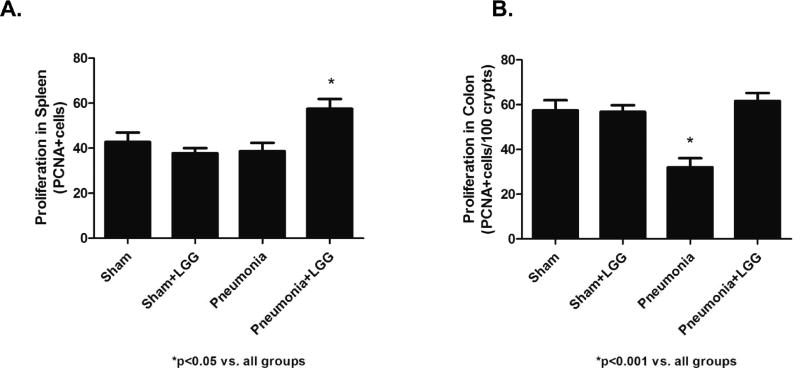

P. aeruginosa induced pneumonia leads to increased apoptosis and decreased proliferation in the intestine and spleen contributing to reduction in survival following experimental pneumonia (27). We have recently shown that LGG treatment significantly increases survival in the pneumonia model (21). To determine whether the improved survival may be related to improved intestinal and splenic homeostasis, colonic and splenic apoptosis was assayed by CC33 staining and also by morphological criteria in H&E stained sections and by PCNA staining to determine proliferation. At 12h, pneumonia mice exhibited significantly increased colonic epithelial apoptosis and splenic apoptosis compared to shams (P<0.05). In contrast, pneumonia mice treated with LGG had significantly decreased (P<0.05) colonic and splenic apoptosis, with levels similar to those seen in sham mice (Figure 4A, B, C, D). Following pneumonia, mice exhibited a significant decrease (P<0.001) in proliferation of the colonic epithelium and splenocytes compared with sham mice at 12h time point. Interestingly, the proliferative response in pneumonia animals treated with LGG was normalized (P<0.001) to levels observed in sham mice in both, colon and spleen (Figure 5A, B).

Figure 4. Effect of LGG treatment on apoptosis in spleen and colon.

(A, B) Apoptosis in spleen of pneumonia mice was significantly increased by both cleaved caspase-3 (CC3) (P<0.05) and H&E (P<0.0001) compared to shams. LGG treatment caused significant decrease of apoptosis in mice treated with LGG (CC3: P<0.05; H&E P<0.0001). (C, D) Apoptosis in colon of pneumonia mice was significantly increased by both cleaved caspase-3 (CC3) (P<0.05) and H&E (P<0.0001) compared to shams. LGG treatment caused significant decrease of apoptosis in mice treated with LGG (CC3: P<0.05; H&E P<0.0001). 12h time point; Shams n=4 per group; Pneumonia, Pneumonia+LGG n=5 per group. Data are expressed as the mean ± SE.

Figure 5. Effect of LGG treatment on proliferation in spleen and colon.

(A) The number of PCNA positive cells was significantly increased in spleen of pneumonia mice treated with LGG compared to all other groups (P<0.05). (B) The number of PCNA positive cells was significantly decreased in colon of mice with pneumonia compared to shams (P<0.001) and normalized in colon of mice treated with LGG (P<0.001). 12h time point; Shams n=4 per group; Pneumonia, Pneumonia+LGG n=5 per group. Data are expressed as the mean ± SE.

LGG treatment impacts mRNA expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in spleen and colon following P. aeruginosa pneumonia

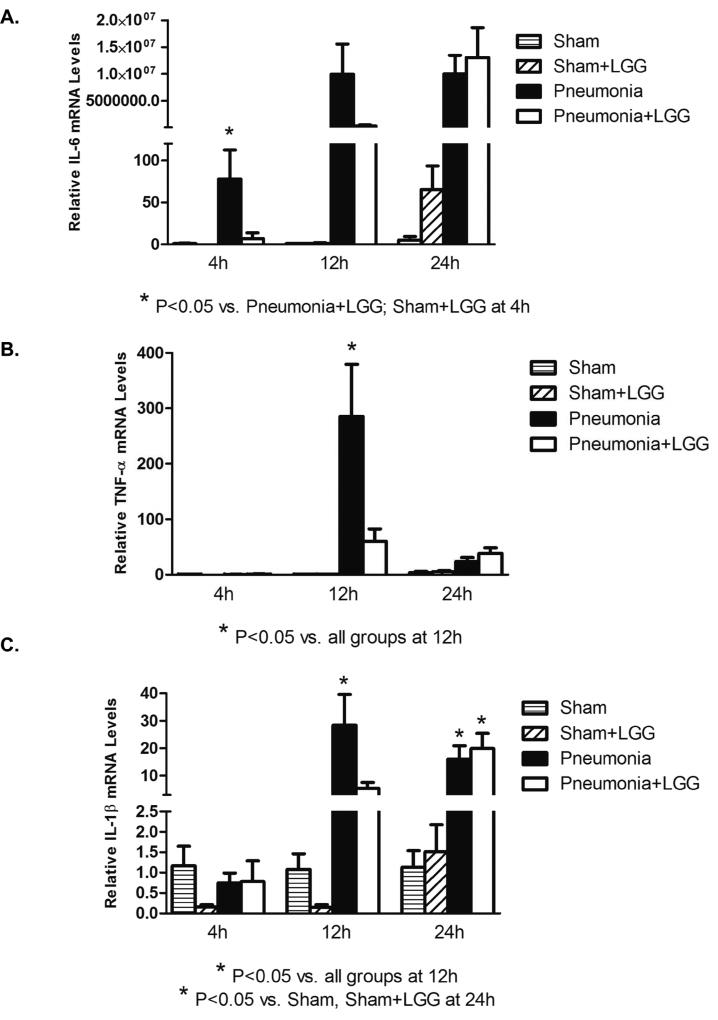

The spleen and intestine are two major immune organs involved in the innate immune response to infection. Gene expression for pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β were significantly elevated in the spleen of P. aeruginosa pneumonia mice at 12h post-pneumonia when compared to sham mice (P<0.05) and treatment with LGG significantly reduced these levels (P<0.05). Only IL-6 was elevated at 4h post-pneumonia and treatment with LGG attenuated this rise. (Figure 6A, B, C).

Figure 6. Effect of LGG treatment on cytokine expression in spleen.

Reverse transcription and real-time PCR assays were performed to quantify steady-state mRNA levels of IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β in spleen at 4h, 12h and 24h. (A) IL-6 was significantly elevated in the spleen of mice with pneumonia and treatment with LGG led to significantly reduced IL-6 levels (P < 0.05) compared to control mice with pneumonia at 4h timepoint. No significant differences were observed at later timepoint between pneumonia and pneumonia+LGG groups. (B) TNF-α was significantly higher in spleen of pneumonia mice compared to shams (P<0.05) and LGG decreased these levels significantly (P<0.05) at 12h timepoint. No significant changes between the groups were observed at 4h or 24h timepoints. (C) IL-1β was significantly increased in spleen of pneumonia mice when compared to shams (P<0.05) and LGG significantly reduced these levels (P<0.05) at 12h. No significant differences were observed at 4h or 24h timepoints between pneumonia and pneumonia+LGG groups. Shams n=3–4 per group; Pneumonia, Pneumonia+LGG n=5–8 per group. Data are expressed as the mean ± SE.

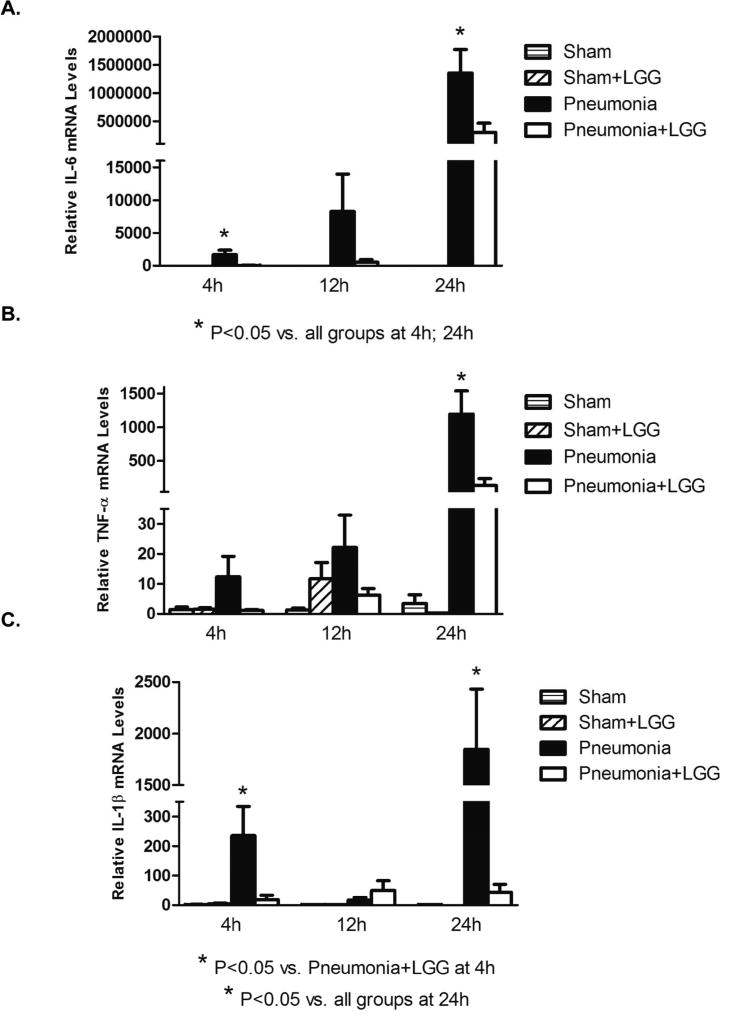

In the colon, gene expressions of IL-6 and IL-1β were significantly elevated in the pneumonia mice compared to shams (P<0.05) and reduced significantly with LGG treatment (P<0.05) at 4h post-pneumonia and at the later 24h time point (Figure 7A, C). TNF-α was significantly higher in the untreated pneumonia group than in shams (P<0.05) and treatment with LGG significantly reduced this expression (P<0.05) (Figure 7B).

Figure 7. Effect of LGG treatment on cytokine expression in colon.

Reverse transcription and real-time PCR assays were performed to quantify steady-state mRNA levels of IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β in colon at 4h, 12h and 24h. (A) IL-6 was significantly elevated in the colon of mice with pneumonia and treatment with LGG led to significantly reduced IL-6 levels (P < 0.05) compared to control mice with pneumonia at 4h and 24h timepoints. The same trend was observed between pneumonia and pneumonia+LGG groups at 12h but it did not reached significance. (B) TNF-α was significantly higher in colon of pneumonia mice compared to shams (P<0.05) and LGG decreased these levels significantly (P<0.05) at 24h timepoint. No significant changes between the groups were observed at 4h or 12h timepoints. (C) IL-1β was increased in colon of pneumonia and LGG significantly reduced these levels (P<0.05) at 4h and 24h timepoints. No significant differences were observed at 12h timepoint between experimental groups. Shams n=3–4 per group; Pneumonia, Pneumonia+LGG n=5–8 per group. Data are expressed as the mean ± SE.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates for the first time that Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG) can attenuate loss of gut barrier homeostasis and gut barrier function following P. aeruginosa pneumonia. Further, to our knowledge this is among the first descriptions of a probiotic maintaining gut barrier function and homeostasis in a pneumonia model in general. This improved gut barrier function following LGG treatment was associated with normalization of claudin-2 expression, a “leaky” gut barrier associated protein, increased mucin secretion and layer formation, and increased Muc2 (key mucin in colon tissue) expression. Further, apoptosis was reduced and loss of cell proliferation attenuated in the colon and the spleen following LGG treatment. Finally, local gut pro-inflammatory cytokine expression and splenic inflammatory cytokine expression was attenuated in LGG treated animals.

We have previously shown that LGG can improve survival, reduce lung injury and markedly reduce bacteremia and lung BAL bacterial counts following P. aeruginosa pneumonia (21). In this study we further explored possible mechanistic targets to help explain these previously observed outcome benefits. As probiotics have been shown to improve gut barrier function in other models of shock (17) we hypothesized that the improved survival and reduced bacteremia may possibly be related to improved gut barrier function. Our findings confirm that LGG can improve gut barrier function, which may lead to reduced bacterial translocation and bacteremia as previously observed by LGG treatment in this model (21). Further, reduced gut apoptosis via transgenic gut bcl-2 overexpression has been shown to be responsible for improved survival from a similar experimental P. aeruginosa pneumonia model (8). Our current data indicates that LGG can similarly reduce gut epithelial apoptosis and this is correlated with our previously observed survival benefit following LGG treatment (21). In addition, splenic apoptosis has been correlated with increased mortality in P. aeruginosa pneumonia and sepsis due to loss of immune function (27). LGG treatment was able to reduce pneumonia-mediated apoptosis and enhance proliferation in this vital immune organ, distant from the gut. We speculate that this enhances the immune response to P. aeruginosa pneumonia and plays a role in the reduced bacteremia and mortality we have previously observed following LGG treatment in this model (21).

Tight junction proteins play an important role in intestinal integrity and gut barrier function. Claudin-2 is considered to be a key protein associated with impaired gut barrier function, (i.e. “leaky” protein) and its higher expression is linked to increased intestinal permeability (25). Previous data has shown that probiotics can attenuate increased claudin-2 expression in chronic intestinal inflammation models (28) and experimental pancreatitis (29). In our model, pneumonia led to an increase in gut claudin-2 expression, which was attenuated by LGG therapy. The role of LGG in effecting other tight junction proteins following pneumonia and sepsis is an area of further research that is key to elucidate and we are currently exploring.

The mucus layer and mucins also play a vital role in maintaining gut barrier homeostasis and are the first line of defense against bacterial invasion and loss of the mucin layer plays a role in the evolution of dysbiosis (30). Thus, maintenance of the intestinal mucus layer may be a vital component of maintenance of gut barrier function in sepsis and critical illness. Data in in vitro models and limited in vivo models indicate probiotics may play a role in upregulating mucin expression. Our data demonstrate that pneumonia leads to loss of mucin secretion and layer formation in the colon. Further, Muc2 expression, the key mucin in barrier formation in the colon, is decreased following pneumonia. Our results show that LGG can restore mucin secretion and increase Muc2 expression. Additional research is needed to further explore the mechanisms by which LGG increases Muc2 expression following pneumonia and sepsis.

The pathophysiology of disseminated bacterial infection and septic shock is characterized by an often exaggerated and dysregulated inflammatory response (31). Early inhibition of the transcription factor NFκB activation and cytokine message expression correlates with improved outcome in sepsis (32). Probiotics have been shown to confer beneficial effects on intestinal immunity (18, 19). Specifically, probiotic intervention has been shown to protect against gut-derived sepsis caused by Pseudomonas in immunocompromised mice by decreasing TNF-α and IL-1β (33). Our current results in P. aeruginosa pneumonia also show an increase in TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 gene-expression in the colon of control animals at 24 hours. LGG treatment attenuated these increases in pro-inflammatory cytokine expression at 24 hours. Cytokine expression in the spleen increased at earlier timepoints with significant elevations of IL-6 occurring 4 hours after induction of pneumonia and at 12 hours for TNF-α and IL-1β. LGG treatment attenuated the early rise in IL-6 at 4 hours post-pneumonia and TNF-α and IL-1β at 12 hours post-pneumonia. IL-6 and Il-1β increased in both control and LGG animals at 24 hours in the spleen, thus LGG appeared to reduce or slow the early rise in pro-inflammatory cytokine expression, but not prevent it at 24 hours.

In conclusion, our data indicate that LGG can improve gut barrier homeostasis and reduce gut inflammation following P. aeruginosa pneumonia. This was accompanied by reduced apoptosis, improved cell proliferation, and reduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines gene expression in the spleen. The effect of LGG on key gut barrier components, including reduced gut apoptosis, enhanced mucin barrier formation and Muc2 expression, and potential effects on tight junction proteins are all targets for future mechanistic explorations of the pathways responsible for the observed survival benefit of probiotics in pneumonia (21). Further, this data provides potential mechanistic explanations for existing clinical trial data showing probiotic therapy can reduce ventilator associated pneumonia (10, 12, 34) and perhaps specifically P. aeruginosa pneumonia (11) in critically ill patients.

Acknowledgments

DISCLOSURE OF FUNDING: Dr. Wischmeyer received support from the NIH (R01 GM078312 for this work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

No conflicts of interest are reported for any authors of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Vincent JL, Rello J, Marshall J, Silva E, Anzueto A, Martin CD, et al. International study of the prevalence and outcomes of infection in intensive care units. JAMA. 2009;302(21):2323–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McDonald D, Ackermann G, Khailova L, Baird C, Heyland D, Kozar R, et al. Extreme Dysbiosis of the Microbiome in Critical Illness. mSphere. 2016;1(4) doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00199-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wischmeyer PE, McDonald D, Knight R. Role of the microbiome, probiotics, and 'dysbiosis therapy' in critical illness. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2016;22(4):347–53. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mittal R, Coopersmith CM. Redefining the gut as the motor of critical illness. Trends in molecular medicine. 2014;20(4):214–23. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark JA, Coopersmith CM. Intestinal crosstalk: a new paradigm for understanding the gut as the "motor" of critical illness. Shock. 2007;28(4):384–93. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e31805569df. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mainous MR, Ertel W, Chaudry IH, Deitch EA. The gut: a cytokine-generating organ in systemic inflammation? Shock. 1995;4(3):193–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark JA, Gan H, Samocha AJ, Fox AC, Buchman TG, Coopersmith CM. Enterocyte-specific epidermal growth factor prevents barrier dysfunction and improves mortality in murine peritonitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;297(3):G471–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00012.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coopersmith CM, Stromberg PE, Dunne WM, Davis CG, Amiot DM, 2nd, Buchman TG, et al. Inhibition of intestinal epithelial apoptosis and survival in a murine model of pneumonia-induced sepsis. JAMA. 2002;287(13):1716–21. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.13.1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andrade ME, Araujo RS, de Barros PA, Soares AD, Abrantes FA, Generoso SV, et al. The role of immunomodulators on intestinal barrier homeostasis in experimental models. Clinical nutrition. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2015.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morrow LE, Kollef MH, Casale TB. Probiotic prophylaxis of ventilator-associated pneumonia: a blinded, randomized, controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(8):1058–64. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200912-1853OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang J, Liu KX, Ariani F, Tao LL, Zhang J, Qu JM. Probiotics for preventing ventilator-associated pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of high-quality randomized controlled trials. PloS one. 2013;8(12):e83934. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manzanares W, Lemieux M, Langlois P, Wischmeyer PE. Probiotic and synbiotic therapy in critical illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Critical care. 2016;20:262. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1434-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petrof EO, Dhaliwal R, Manzanares W, Johnstone J, Cook D, Heyland DK. Probiotics in the critically ill: a systematic review of the randomized trial evidence. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(12):3290–302. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318260cc33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shanahan F. Probiotics and inflammatory bowel disease: from fads and fantasy to facts and future. Br J Nutr. 2002;88(Suppl 1):S5–9. doi: 10.1079/BJN2002624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yan F, Cao H, Cover TL, Whitehead R, Washington MK, Polk DB. Soluble proteins produced by probiotic bacteria regulate intestinal epithelial cell survival and growth. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(2):562–75. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alberda C, Gramlich L, Meddings J, Field C, McCargar L, Kutsogiannis D, et al. Effects of probiotic therapy in critically ill patients: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85(3):816–23. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.3.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luyer MD, Buurman WA, Hadfoune M, Speelmans G, Knol J, Jacobs JA, et al. Strain-specific effects of probiotics on gut barrier integrity following hemorrhagic shock. Infect Immun. 2005;73(6):3686–92. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.6.3686-3692.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aguero G, Villena J, Racedo S, Haro C, Alvarez S. Beneficial immunomodulatory activity of Lactobacillus casei in malnourished mice pneumonia: effect on inflammation and coagulation. Nutrition. 2006;22(7–8):810–9. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tok D, Ilkgul O, Bengmark S, Aydede H, Erhan Y, Taneli F, et al. Pretreatment with pro- and synbiotics reduces peritonitis-induced acute lung injury in rats. J Trauma. 2007;62(4):880–5. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000236019.00650.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alvarez S, Herrero C, Bru E, Perdigon G. Effect of Lactobacillus casei and yogurt administration on prevention of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in young mice. J Food Prot. 2001;64(11):1768–74. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-64.11.1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khailova L, Baird CH, Rush AA, McNamee EN, Wischmeyer PE. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG improves outcome in experimental pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia: potential role of regulatory T cells. Shock. 2013;40(6):496–503. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garau J, Gomez L. Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2003;16(2):135–43. doi: 10.1097/00001432-200304000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vyas D, Robertson CM, Stromberg PE, Martin JR, Dunne WM, Houchen CW, et al. Epithelial apoptosis in mechanistically distinct methods of injury in the murine small intestine. Histol Histopathol. 2007;22(6):623–30. doi: 10.14670/hh-22.623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu P, Martin CM. Increased gut permeability and bacterial translocation in Pseudomonas pneumonia-induced sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(7):2573–7. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200007000-00065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krug SM, Schulzke JD, Fromm M. Tight junction, selective permeability, and related diseases. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2014;36:166–76. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mattar AF, Teitelbaum DH, Drongowski RA, Yongyi F, Harmon CM, Coran AG. Probiotics up-regulate MUC-2 mucin gene expression in a Caco-2 cell-culture model. Pediatr Surg Int. 2002;18(7):586–90. doi: 10.1007/s00383-002-0855-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dominguez JA, Vithayathil PJ, Khailova L, Lawrance CP, Samocha AJ, Jung E, et al. Epidermal growth factor improves survival and prevents intestinal injury in a murine model of pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. Shock. 2011;36(4):381–9. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31822793c4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Corridoni D, Pastorelli L, Mattioli B, Locovei S, Ishikawa D, Arseneau KO, et al. Probiotic bacteria regulate intestinal epithelial permeability in experimental ileitis by a TNF-dependent mechanism. PloS one. 2012;7(7):e42067. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lutgendorff F, Nijmeijer RM, Sandstrom PA, Trulsson LM, Magnusson KE, Timmerman HM, et al. Probiotics prevent intestinal barrier dysfunction in acute pancreatitis in rats via induction of ileal mucosal glutathione biosynthesis. PloS one. 2009;4(2):e4512. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen SJ, Liu XW, Liu JP, Yang XY, Lu FG. Ulcerative colitis as a polymicrobial infection characterized by sustained broken mucus barrier. World journal of gastroenterology : WJG. 2014;20(28):9468–75. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i28.9468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kono Y, Inomata M, Hagiwara S, Shiraishi N, Noguchi T, Kitano S. A newly synthetic vitamin E derivative, E-Ant-S-GS, attenuates lung injury caused by cecal ligation and puncture-induced sepsis in rats. Surgery. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams DL, Ha T, Li C, Kalbfleisch JH, Laffan JJ, Ferguson DA. Inhibiting early activation of tissue nuclear factor-kappa B and nuclear factor interleukin 6 with (1-->3)-beta-D-glucan increases long-term survival in polymicrobial sepsis. Surgery. 1999;126(1):54–65. doi: 10.1067/msy.1999.99058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matsumoto T, Ishikawa H, Tateda K, Yaeshima T, Ishibashi N, Yamaguchi K. Oral administration of Bifidobacterium longum prevents gut-derived Pseudomonas aeruginosa sepsis in mice. J Appl Microbiol. 2008;104(3):672–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2007.03593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu KX, Zhu YG, Zhang J, Tao LL, Lee JW, Wang XD, et al. Probiotics' effects on the incidence of nosocomial pneumonia in critically ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Critical care. 2012;16(3):R109. doi: 10.1186/cc11398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]