Abstract

Objective

The maintenance and expansion of β-cell mass rely on their proliferation, which reaches its peak in the neonatal stage. β-cell proliferation was found to rely on cells of the islet microenvironment. We hypothesized that pericytes, which are components of the islet vasculature, support neonatal β-cell proliferation.

Methods

To test our hypothesis, we combined in vivo and in vitro approaches. Briefly, we used a Diphtheria toxin-based transgenic mouse system to specifically deplete neonatal pancreatic pericytes in vivo. We further cultured neonatal pericytes isolated from the neonatal pancreas and combined the use of a β-cell line and primary cultured mouse β-cells.

Results

Our findings indicate that neonatal pancreatic pericytes are required and sufficient for β-cell proliferation. We observed impaired proliferation of neonatal β-cells upon in vivo depletion of pancreatic pericytes. Furthermore, exposure to pericyte-conditioned medium stimulated proliferation in cultured β-cells.

Conclusions

This study introduces pancreatic pericytes as regulators of neonatal β-cell proliferation. In addition to advancing current understanding of the physiological β-cell replication process, these findings could facilitate the development of protocols aimed at expending these cells as a potential cure for diabetes.

Keywords: Beta-cells, Pericytes, Neonatal pancreas, Islets, Vasculature

Highlights

-

•

Pancreatic pericytes support proliferation of neonatal β-cells in vivo.

-

•

Factors produced by neonatal pancreatic pericytes stimulate adult β-cell proliferation in vitro.

-

•

Pericyte-dependent β-cell expansion requires β1-integrin signaling.

1. Introduction

Establishment of β-cell mass is largely dictated during the embryonic and neonatal stages [1], [2], [3]. In the embryo, new β-cells are formed by differentiation of pancreatic endocrine precursors, followed by proliferation of differentiated β-cells [3], [4], [5]. After birth, the major route of β-cell generation is their replication [1], [6], [7]. However, β-cell proliferation rates decline with age in both humans and rodents and are significantly higher during the neonatal period than during adulthood [2], [3], [8], [9], [10]. In humans, proliferation of β-cells begins shortly after birth, continues at its highest rate for about a year, and then rapidly declines in early childhood [2], [9]. In rodents, the β-cell proliferation rate peaks during the first week of life, and rapidly declines shortly thereafter [3], [8]. A further decline in β-cell proliferation rates is observed as humans and rodents age, when the proliferation index of these cells approaches zero during adulthood [2], [3], [9], [11]. However, adult β-cells maintain an ability for compensatory proliferation in response to increased metabolic demand or injury [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19].

β-cells respond to cues provided by cells of their microenvironment, in which endothelial, neuronal, and immune cells have been shown to promote adult β-cell proliferation [20], [21], [22], [23], [24]. In addition to endothelial cells, the dense capillary network of islets contains pericytes, which form a single discontinuous layer around smaller vessels and are intimately associated with endothelial cells [25]. Interactions between endothelial cells and pericytes are required for assembling the vascular basement membrane (BM) [26], [27], which, in the islet, was shown to support β-cell proliferation and function [20], [28]. Together with vascular smooth muscle cells (vSMCs), which surround large blood vessels, pericytes constitute a class of mesenchymal cells termed ‘mural cells’ [27]. The embryonic pancreatic mesenchyme was shown by us and others to support the proliferation of pancreatic progenitors and differentiated β-cells [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35]. After birth, pericytes constitute a major part of the mesenchymal cell population in the pancreas [25], [36]. However, the role of pancreatic pericytes in postnatal β-cell proliferation awaits investigation.

Here, we investigated the ability of neonatal pancreatic pericytes to promote β-cell proliferation both in vitro and in vivo. Our findings indicate that the conditioned medium of cultured neonatal pericytes stimulates the proliferation of both a β-cell tumor line, βTC-tet [37], and primary cultured adult β-cells. Furthermore, pericyte-conditioned medium induced β-cell expansion in an integrin β1-dependent manner, implicating the involvement of BM components in this process. Lastly, we used iDTR (inducible diphtheria toxin [DT] receptor) [38] and Nkx3.2-Cre [33], [39] mouse lines to target and deplete pericytes in the neonatal pancreas and analyzed the resulting effect on β-cell proliferation. We show that partial pericyte depletion was sufficient to reduce the rate of neonatal β-cell proliferation in vivo. To conclude, our results point to a pivotal role of pancreatic pericytes in neonatal β-cell proliferation.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Mice

Mice were maintained according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Tel Aviv University. All mice were maintained on a C57BL/6 background. Nkx3.2-Cre (Nkx3-2tm1(cre)Wez) [39] mice were a generous gift from Warren Zimmer (Texas A&M). R26-YFP (Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1(EYFP)Cos) [40] and iDTR (Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1(HBEGF)Awai) [38] mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories. Wild-type mice were purchased from Envigo, Ltd. When indicated, mice were i.p. injected with a single dose of 0.25 ng/g body weight Diphtheria Toxin (DT; List) diluted in PBS.

2.2. Islet isolation

Collagenase P (0.8 mg/ml; Roche) diluted in RPMI (Gibco) was injected through the common bile duct into the pancreas of a euthanized adult mouse. Dissected pancreatic tissue was incubated for 10–15 min at 37 °C, followed by a gradient separation with Histopaque 1119 (Sigma) for 20 min at 4 °C. Islets were collected from the gradient interface, followed by their manual collection.

2.3. Flow-cytometry

For cell sorting, dissected pancreatic tissues were digested with 0.4 mg/ml collagenase P (Roche) and 0.1 ng/ml DNase (Sigma) diluted in HBSS for 30 min at 37 °C with agitation, followed by cell filtration [41]. Cells were suspended in PBS containing 5% FCS and 5 mM EDTA and sorted based on their yellow fluorescence by FACS Aria (BD). For staining of cell surface markers, cells were isolated as described above and stained with biotin-conjugated anti-PDGFRβ (Platelet-derived Growth Factor Receptor β) antibody (Catalog #13-1402, Affymetrix) followed by incubation with Allophycocyanin-labeled Streptavidin (Catalog #17-4317-82, Affymetrix). Cells were analyzed by a Gallios cytometer (Beckman Coulter) using Kaluza software (Beckman Coulter). For analysis of cell proliferation, single-cell suspension was obtained by incubating islets with 0.05% Trypsin and 0.02% EDTA solution (Biological Industries) at 37 °C for 5 min with agitation, or by collecting βTC-tet cells with 0.05% Trypsin and 0.02% EDTA solution (Biological Industries). Cells were fixed in 70% ethanol at −20 °C overnight, suspended in PBS containing 1–2% FBS and 0.09% sodium azide, and then immunostained with Fluorescein-conjugated anti-Ki67 (Catalog #11-5698-82, eBioscience or Catalog #556026, BD) antibody. Islet cells were further stained with guinea pig anti-insulin (Catalog #A0564, Dako) antibody, followed by DyLight 650-conjugated secondary antibody (SA5-10097, Invitrogen). For analyzing proliferation rates, cells were analyzed by a FACS Gallios cytometer (Beckman Coulter) using Kaluza software (Beckman Coulter). For cell counting, cells were analyzed by an Accuri C6 cytometer (BD) using its volumetric counting feature.

2.4. Cell culture

For culturing pericytes, at least 1.5 × 105 sorted cells were cultured in DMEM medium (Gibco) containing 10% FCS (Hyclone), 1% l-Glutamine (Biological Industries) and 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin solution (Biological Industries) (‘complete DMEM’). Cells were sub-cultured weekly or when about 90% confluent, using 0.25% Trypsin solution with 0.05% EDTA (Biological Industries). Up to their third passage, cells were plated on collagen-coated plates (Catalog #FAL354236, Corning). Media were collected from cells in their fourth passage, passed through a 22 μm filter to exclude cells, supplemented with proteases inhibitor (Roche), and then stored at −80 °C. Islets and βTC-tet cells were grown in complete DMEM. Growth arrest of βTC-tet cells was induced by supplementing culture medium with 1 μg/ml tetracycline (Sigma) for 10 days before a proliferation assay was performed [37], [42]. For heat inactivation, pericyte-conditioned medium and complete DMEM were incubated at 62 °C for 20 min. For blocking of β1 integrin signaling, pericyte-conditioned medium was supplemented with either hamster anti-β1 integrin (CD29) antibody (Catalog #555003, BD) or hamster IgM (Catalog #553958, BD) as a control. Cultured pericytes were imaged using a Nikon Eclipse Ti-E epifluorescence inverted microscope.

2.5. Immunofluorescence and morphometric analyses

Dissected pancreatic tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 4 h. Tissue was transferred to 30% sucrose solution overnight at 4 °C, followed by embedding in Optimal Cutting Temperature compound (OCT, Tissue-Tek) and cryopreservation. 11-μm-thick tissue sections were stained with the following primary antibodies: guinea pig anti-insulin (Catalog #A0564, Dako), rabbit anti- αSMA (α smooth muscle actin; Catalog #Ab5694, Abcam), Ki67 (Catalog #RM-9106, Thermo Scientific), and NG2 (Neural Glial antigen 2; Catalog #AB5320, Millipore), and rat anti-PECAM1 (Platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1; Catalog #553370, BD) antibodies, followed by secondary fluorescent antibodies (AlexaFluor, Invitrogen). For TUNEL (Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling) assays, the Fluorescein In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit (Roche) was used according to manufacturer's protocol. Stained sections were mounted using Vectashield antifade mounting medium with DAPI (Vector). Images were acquired using an SP8 confocal microscope (Leica) or a Keyence BZ-9000 microscope (Biorevo). For analysis of islet endothelial and pericyte coverage, sections at least 50 μm apart were stained as described. Islets were defined as insulin+ areas. NG2+ or PECAM1+ areas within the islets, as well as insulin+ areas, were measured using ImageJ software (NIH). For cell proliferation analysis, sections at least 50 μm apart were stained as described. Images were analyzed manually blind to genotype; at least 300 insulin+ cells were analyzed for each pup.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Paired data were evaluated using Student's two-tailed t-test.

3. Results

3.1. Culturing neonatal pancreatic pericytes

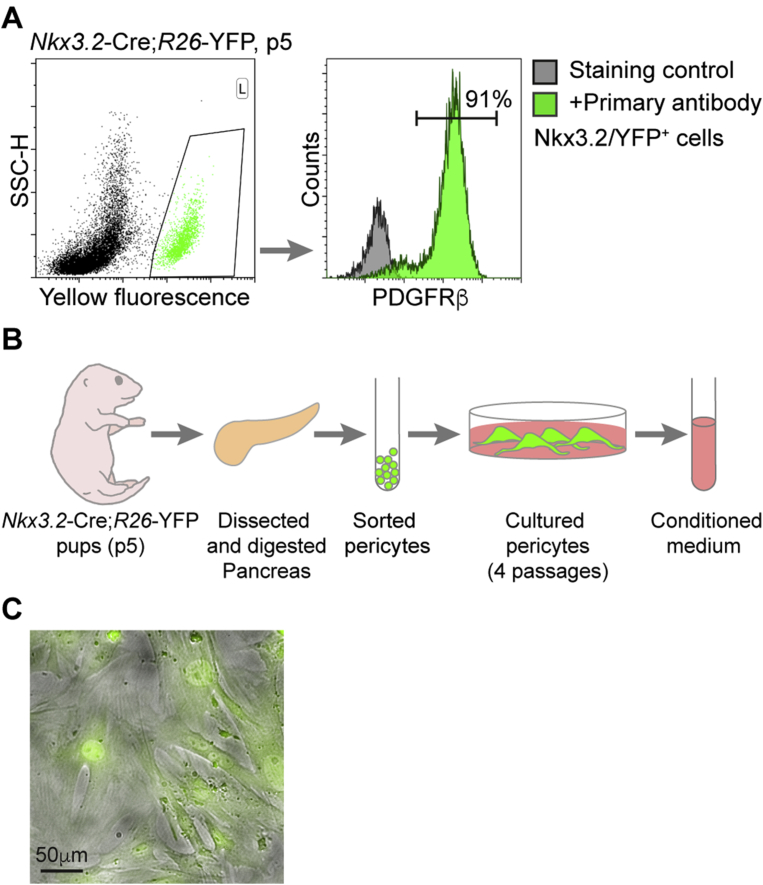

In order to test the ability of neonatal pancreatic pericytes to promote β-cell replication in vitro, we set out to isolate and culture them. To this end, we sorted YFP-labeled cells from the pancreas of Nkx3.2-Cre;R26-YFP pups at postnatal day 5 (p5). During development, Nkx3.2 (Bapx1) is expressed in gut, stomach, and pancreatic mesenchyme, as well as in skeletal somites [43], [44]. In the embryonic and adult pancreas, the Nkx3.2-Cre mouse line specifically targets mesenchymal cells, which, in the adult, consist of pericytes and vSMCs [27], [33], [36], [41]. To determine if the Nkx3.2-Cre mouse line targets pancreatic pericytes at the neonatal age, as in adults, we analyzed fluorescently labeled (‘Nkx3.2/YFP+’) cells of p5 Nkx3.2-Cre;R26-YFP pancreatic tissue for PDGFRβ, which is expressed on the surface of pericytes but not on that of vSMCs [27]. As shown in Figure 1A, our flow-cytometry analysis revealed that ∼90% of Nkx3.2/YFP+ cells in the p5 pancreas express PDGFRβ, displaying their pericytic identity. PDGFRβ-negative Nkx3.2/YFP+ cells represent vSMCs, which are targeted by the Nkx3.2-Cre mouse line but do not express this receptor [27], [36]. To conclude, our results indicate that the Nkx3.2-Cre mouse line efficiently targets pericytes in the neonatal pancreas.

Figure 1.

Culturing neonatal pancreatic pericytes. A) Flow-cytometry analysis of digested pancreatic tissue. Left, Dotplot showing the presence of a yellow fluorescent cell population (gated green cells; ‘Nkx3.2/YFP+ cells’) in the pancreas of Nkx3.2-Cre;R26-YFP at postnatal day 5 (p5). Right, Green histogram (‘+Primary antibody’) showing the staining of Nkx3.2/YFP+ cells (as gated in left panel) for the pericytic marker PDGFRβ. Gray histogram showing the analysis of Nkx3.2/YFP+ cells without the addition of the primary antibody (‘Staining control’). The number represents the percentage of PDGFRβ-stained cells from the total Nkx3.2/YFP+ cell population (as indicated by a horizontal line). Note that the vast majority of Nkx3.2/YFP+ cells express this pericytes' marker. B) Schematic illustration of cultured neonatal pancreatic pericytes. Pancreatic tissues of Nkx3.2-Cre;R26-YFP p5 pups were dissected and digested to obtain a single cell suspension. Pericytes were FACS sorted based on their yellow fluorescence (as shown in A′, Nkx3.2/YFP+ cells), and cultured in complete DMEM medium. During the cells' fourth passage, their conditioned media were collected. C) Cultured neonatal pancreatic pericytes. A yellow fluorescent image (showed in green for easier visualization) overlaid on top of a brightfield image of cultured Nkx3.2/YFP+ cells (as described in B′) during their fourth passage. Representative field is shown. Note extension of cytoplasmic process by cultured cells.

Next, pericytes from neonatal pancreatic tissue were isolated and cultured to collect their conditioned media. To culture pericytes, dissected pancreatic tissues of p5 Nkx3.2-Cre;R26-YFP pups were digested to obtain single cells, followed by sorting of Nkx3.2/YFP+ cells by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) and culturing of sorted cells (Illustrated in Figure 1B). Yellow fluorescence of cultures cells verified they were indeed sorted Nkx3.2/YFP+ pericytes (Figure 1C). Furthermore, all cultured cells extended cytoplasmic processes typical to pericytes. After four passages, the cell-conditioned medium was collected and filtered to exclude cells (illustrated in Figure 1B).

3.2. Pericyte-conditioned medium stimulates β-cell proliferation in vitro

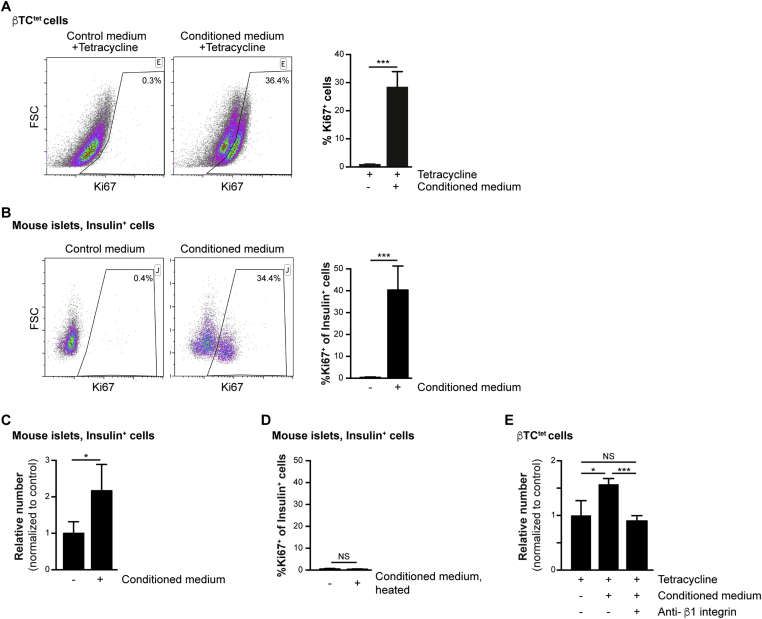

To analyze the effect of neonatal pericyte-conditioned medium on β-cell proliferation in vitro, we analyzed the response of both the β-cell line βTC-tet and primary mouse adult β-cells to this medium. Immortalization of βTC-tet cells was achieved through conditional expression of SV40 (Simian Vacuolating Virus 40) large T-antigen under the control of rat Ins2 promoter [37], [42]. The expression of the T-antigen under the tetracycline operon regulatory system (tet) allows for its shut-off upon exposure to tetracycline. Thus, in the presence of this antibiotic, the proliferation of βTC-tet cells becomes dependent on extrinsic factors [42], [45]. To test the ability of neonatal pericyte-conditioned medium to promote proliferation of βTC-tet cells, we incubated tetracycline-treated cells with this medium. To assess the level of cell proliferation, cells were stained for the proliferative marker Ki67 and analyzed by flow-cytometry. As shown in Figure 2A, exposure to pericyte-conditioned medium promoted the proliferation of about a third of the analyzed βTC-tet cells.

Figure 2.

Increased β-cell proliferation upon exposure to pericyte-conditioned medium. A) Tetracycline-treated βTC-tet cells were cultured in either control (complete DMEM; ‘Control medium’) or neonatal pericyte-conditioned (‘Conditioned medium’; described in Figure 1B) medium, both supplemented with tetracycline. After incubation for 96 h, cells were fixed and stained for the proliferative marker Ki67. Left, representative dotplots showing flow-cytometry analysis of Ki67 expression by βTC-tet cells. Gated are Ki67+ cells; the numbers represent the percentage of gated cells out of the analyzed cell population. Right, Bar diagrams (mean ± SD) represent the percentage of Ki67+ cells. N = 3. ***P < 0.005 (Student's t-test), as compared to the control medium. A representative of three independent experiments is shown. B) Isolated islets from 3-month-old wild-type mice were cultured in either control (complete DMEM; ‘Control medium’) or neonatal pericyte-conditioned (‘Conditioned medium’; described in Figure 1B) medium for 24 h. Islets were dispersed to single cells, fixed, and stained for insulin and the proliferative marker Ki67. Left, representative dotplots showing flow-cytometry analysis of Ki67 expression by insulin+ cells. Gated are Ki67+ cells; the numbers represent the percentage of gated cells out of the total insulin+ cell population. Right, Bar diagrams (mean ± SD) represent the percentage of Ki67+ out of the total number of insulin+ cells. N = 4. ***P < 0.005 (Student's t-test), as compared to the control media. A representative of four independent experiments is shown. C) Isolated islets were cultured as described in B′ for 72 h. Islets were dispersed to single cells, fixed and stained for insulin. Bar diagrams (mean ± SD) represent the relative number of insulin+ cells, normalized to islets incubated with control medium. N = 3–4. *P < 0.05 (Student's t-test). D) Control (complete DMEM) and neonatal pericyte-conditioned (‘conditioned medium’; as described in Figure 1B) medium were heated to 62 °C for 20 min. Isolated islets from 3-month-old wild-type mice were cultured in heated media for 24 h. Islets were dispersed to single cells, fixed and stained for insulin and the proliferative marker Ki67. Bar diagrams (mean ± SD) represent the percentage of Ki67+ out of the total number of insulin+ cells (gated as shown in B′). N = 3–4. NS = non-significant (Student's t-test). E) Tetracycline-treated βTC-tet cells were incubated with control (complete DMEM; tetracycline-supplemented) medium or neonatal pericyte-conditioned medium (‘Conditioned medium’, tetracycline-supplemented) for 96 h. The conditioned medium was supplemented with either anti-β1 integrin blocking antibody (‘Anti-β1 integrin’) or control IgM. Bar diagrams (mean ± SD) represent the relative cell number, normalized to cells incubated with control medium. N = 3. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.005, NS = non-significant (Student's t-test).

Next, we analyzed the ability of the pericyte-conditioned media to promote proliferation of primary cultured adult β-cells. To this end, islets were isolated from 3-month-old mice and cultured in either control or pericyte-conditioned medium. To assess the level of β-cell proliferation, islet cells were dispersed and stained with antibodies against insulin and Ki67, and analyzed by flow-cytometry. As shown in Figure 2B, whereas less than 1% of β-cells cultured in control medium express Ki67, an average of 40% of cells incubated in the presence of pericyte-conditioned medium proliferated. Next, we analyzed for a potential effect on β-cell number. As shown in Figure 2C, the number of β-cells in islets cultured for 72 h in pericyte-conditioned medium was double the number in islets cultured in control medium. Thus, our results indicate that factors secreted by cultured pancreatic pericytes stimulate proliferation of both a β-cell line and primary cultured adult β-cells.

Extracellular matrix (ECM) components, including these found in islets vascular BM, were shown to promote β-cell proliferation [20], [28], [46], [47]. We thus analyzed the contribution of these factors to β-cell proliferation stimulated by pericyte-conditioned medium. First, we analyzed if proliferation of primary β-cells depends on heat-sensitive components (such as proteins) of the medium. Heating the conditioned medium (to 62 °C) prior to islet culture resulted in a low β-cell proliferation rate, which was comparable to their culturing with control media (Figure 2D). This result indicates that pericytes produce heat-sensitive factors, such as BM components and other proteins, to promote β-cell expansion. BM components are recognized by integrins and initiate downstream signaling, and integrins containing the β1 chain were shown to mediate β-cell proliferation [20], [28]. To analyze the contribution of β1 integrin signaling to pericyte-mediated β-cell proliferation, we inhibited it in βTC-tet cells. To this end, we supplemented the pericyte-conditioned medium with a specific anti-β1 integrin blocking antibody. As shown in Figure 2E, blocking β1 integrin signaling inhibited the expansion of βTC-tet cells cultured in pericyte-conditioned medium. Of note, βTC-tet cell number after their culturing in pericyte-conditioned medium supplemented with anti-β1 integrin blocking antibody was comparable to the number of cells cultured in control medium (Figure 2E). Thus, our analysis indicated that neonatal pancreatic pericytes stimulate β-cell proliferation in a β1 integrin-dependent manner.

To conclude, our analysis indicated that neonatal pancreatic pericytes secrete factors that promote β-cell proliferation.

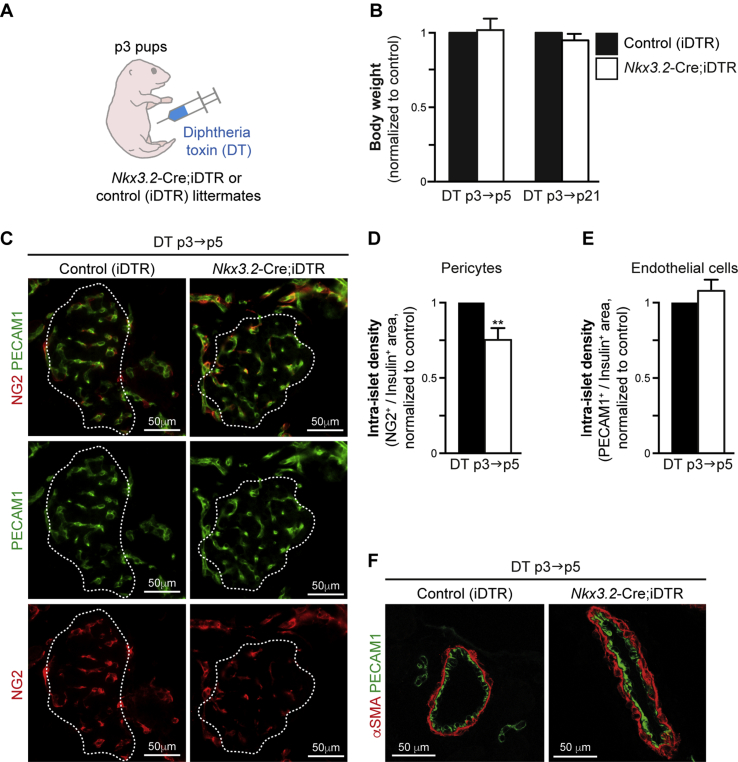

3.3. Diphtheria toxin-mediated depletion of neonatal pancreatic pericytes

To analyze the in vivo role of neonatal pancreatic pericytes, we set out to deplete this cell population using the Diphtheria Toxin Receptor (DTR) system. To deplete pericytes, we generated Nkx3.2-Cre;iDTR mice, which express DTR in a Cre-dependent manner [36]. Cell-specific expression of the iDTR transgene, combined with DT administration, serves as a tool for targeted cell ablation [48], [49]. We have previously used this system to deplete mesenchymal cells from the embryonic pancreas [33], as well as pericytes from the adult pancreas [36] in Nkx3.2-Cre;iDTR mice. To deplete pericytes in neonatal pancreas, Nkx3.2-Cre;iDTR pups as well as control littermates (iDTR-transgenic pups, which do not express -Cre) at p3 were i.p. injected with DT (Figure 3A). In addition to its pancreatic expression, the Nkx3.2-Cre line also displays non-pancreatic expression in the joints and gastro-intestinal mesenchyme [39], [50]. Treating neonatal mice with the DT dose used for treating adult mice (4 ng/gr body weight [36]) attenuated the growth and survival of Nkx3.2-Cre;iDTR transgenic pups. Therefore, we titered the dose of injected DT to ensure that the growth of the pups would be unaffected by the treatment. Our results indicated that injecting p3 Nkx3.2-Cre;iDTR pups with 0.25 ng/gr body weight DT allowed them to grow normally, as manifested by a body weight comparable to their control littermates at ages p5 and p21 (Figure 3B), and their long-term survival. This indicates that weight gain and growth were unaffected in DT-treated Nkx3.2-Cre;iDTR pups.

Figure 3.

Partial depletion of pancreatic pericytes in DT-treated Nkx3.2-Cre;iDTR pups. Nkx3.2-Cre;iDTR transgenic pups and littermate controls (carrying the iDTR transgene, but not the Nkx3.2-Cre transgene; ‘Control [iDTR]’) were i.p. injected with 0.25 ng/gr body weight DT at p3 and analyzed at p5 (‘DT p3→p5’) or p21 (‘DT p3→p21’). A) Schematic illustration of mouse treatment. B) Bar diagram (mean ± SD) showing the relative body weight of DT-treated Nkx3.2-Cre;iDTR (empty bars) and control (black bars, set to ‘1’) littermates at p5 and p21. n = 5. C) Pancreatic tissues of DT-treated p5 Nkx3.2-Cre;iDTR (right) and control (left) mice were stained for NG2 (red) to label pericytes, PECAM1 (green) to label endothelial cells, and insulin to label β-cells. White lines demarcate the outer border of the insulin+ area. Note that all capillaries in control islets contained both endothelial cells and pericytes, whereas some capillaries in Nkx3.2-Cre;iDTR islets contained only endothelial cells. Representative fields are shown. The same imaging parameters were used to analyze Nkx3.2-Cre;iDTR and control tissues. D, E) Bar diagrams (mean ± SD) showing decreased intra-islet pericyte density (D), but not endothelial density (E), in DT-treated p5 Nkx3.2-Cre;iDTR mice (empty bars) compared with a control (black bars, set to ‘1’). Pancreatic tissues were stained as described in C', and the relative ratio of NG2+ or PECAM1+, and the Insulin+ area for each islet was calculated. At least 30 islets per mouse, from sections at least 50 μm apart, were analyzed. N = 3. ***, P < 0.005 (Student's t-test), as compared to control littermates. F) Pancreatic tissues of DT-treated p5 Nkx3.2-Cre;iDTR (right) and control (left) mice were stained for αSMA (red) to label vSMCs, and PECAM1 (green) to label endothelial cells. Representative fields are shown. The same imaging parameters were used to analyze Nkx3.2-Cre;iDTR and control tissues.

To assess pericyte depletion, we measured islet pericyte and endothelial coverage for pups at p5. Our morphometric analysis revealed that DT treatment of Nkx3.2-Cre;iDTR pups led to ∼25% reduction in islet pericyte coverage, identified by the expression of the pericytic marker NG2 (Figure 3C,D) [27]. In contrast, islet coverage by endothelial cells, identified by the expression of PECAM1, remained unchanged (Figure 3C,E). Notably, we did not observe gross changes in the coverage of large pancreatic vessels by vSMCs (identified by the expression of high αSMA levels; Figure 3F) in DT-treated Nkx3.2-Cre;iDTR pups as compared to control. Thus, treatment of Nkx3.2-Cre;iDTR pups with a low DT dose allows partial, but specific, depletion of their islet pericytes without affecting their growth.

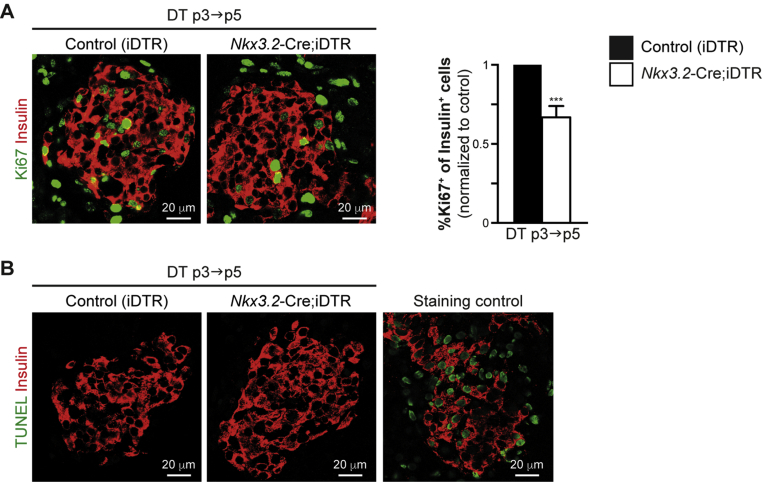

3.4. Depletion of neonatal pancreatic pericytes impairs β-cell proliferation in vivo

To determine whether neonatal pancreatic pericytes are required for β-cell proliferation, we depleted pancreatic pericytes by treating Nkx3.2-Cre;iDTR pups with DT. Determining primary, rather than secondary effects requires studying short-term events. Therefore, Nkx3.2-Cre;iDTR pups and control (iDTR-transgenic pups, which do not express Cre) littermates were treated with 0.25 ng/gr body weight DT at p3 and analyzed 2 days after DT administration, at p5. To analyze the effect of pericyte depletion on β-cell proliferation, we measured the percentage of Ki67+ cells out of the total number of insulin-expressing cells in pancreatic tissues of DT-treated Nkx3.2-Cre;iDTR and control pups by immunofluorescence (Figure 4A). Our morphometric analysis indicated a significant reduction of the portion of proliferating β-cells in DT-treated Nkx3.2-Cre;iDTR mice to about two thirds of that observed in littermate controls (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Reduced neonatal β-cell proliferation rates upon pericyte depletion. Nkx3.2-Cre;iDTR transgenic pups and littermate controls (carrying the iDTR transgene, but not the Nkx3.2-Cre transgene; ‘Control [iDTR]’) were i.p. injected with 0.25 ng/gr body weight DT at p3 and analyzed at p5 (‘DT p3→p5’). A) Pancreatic tissues were stained for insulin to label β-cells (red) and Ki67 (green) to mark proliferative cells. Left, representative fields showing immunofluorescence analysis of Ki67 and insulin. Right, Bar diagrams (mean ± SD) represent the percentage of Ki67+ cells out of the total number of insulin+ cells in DT-treated p5 Nkx3.2-Cre;iDTR mice (empty bars) compared with control (black bars, set to ‘1’), stained as shown in left panels. At least 300 insulin+ cells were analyzed for each mouse. The same imaging parameters were used to analyze Nkx3.2-Cre;iDTR and control tissues. N = 3. ***P < 0.005 (Student's t-test). B) Pancreatic tissues of DT-treated p5 Nkx3.2-Cre;iDTR (middle panel) and control (left panel) were subjected to TUNEL assay (green) to identify dying cells, and were stained for insulin (red) to identify β-cells. The right panel shows similarly stained non-transgenic pancreatic tissue pre-treated with DNase to induce DNA breaks, which served as a positive control for the TUNEL assays (‘staining control’). Representative fields are shown. The same imaging parameters were used to analyze Nkx3.2-Cre;iDTR and control tissues.

The observed reduced β-cell proliferation may result from the impaired survival of these cells. We therefore performed TUNEL assays on pancreatic tissue sections from DT-treated Nkx3.2-Cre;iDTR and control p5 pups to analyze for potential β-cell apoptosis. Our analysis did not indicate β-cell death upon pericyte depletion (Figure 4B).

To conclude, our results indicate that reduced pericyte density impairs β-cell proliferation in vivo, indicating that pancreatic pericytes are required for neonatal β-cell expansion.

4. Discussion

In this study, we provided evidence that pancreatic pericytes play a critical role in promoting the proliferation of neonatal β-cells. Our findings indicate that factors secreted by pericytes isolated from neonatal pancreatic tissue stimulated β-cell proliferation in vitro. Furthermore, we show that this proliferation requires β1 integrin signaling, implicating the involvement of BM components. Finally, we showed an impaired neonatal β-cell proliferation upon depletion of pancreatic pericytes in vivo. Thus, our findings highlight the requirement of the pericyte/β-cell axis in establishing β-cell mass.

Islets are encased within the peri-islet BM and associated interstitial matrix, which contains multiple ECM components [26]. Interestingly, β-cells do not produce their own BM, but rather, rely on ECM components deposited into their niche by other cells, including endothelial cells [20]. The vascular BM, located within and around islets, was shown to support β-cell function and proliferation [20], [28]. Heterotypic interactions of pericytes and endothelial cells are required for vascular BM assembly in many tissues [27] and likely play a similar role in the pancreas. We recently showed that the embryonic and neonatal pancreatic mesenchyme produces laminins along with other BM components [51]. Here, we show that inhibiting β-cells' ability to respond to these cues, by blocking β1 integrin signaling, attenuates their pericyte-dependent proliferation. Our analysis therefore links β-cell proliferation to the production of BM components by pancreatic pericytes.

In addition to ECM components, β-cell proliferation was shown to be induced by an array of secreted growth factors [52]. Others and we reported that the embryonic pancreatic mesenchyme expresses a number of growth factors implicated in β-cell proliferation, including IGF1 (Insulin Growth Factor 1), TGFβ2 (Transforming Growth Factor β 2), TGFβ3, HGF (Hepatocyte Growth Factor), and PDGF [10], [30], [34], [52], [53], [54]. Since these analyses were performed during embryogenesis, it would be of interest to determine whether pancreatic pericytes express growth factors after birth to promote neonatal β-cell expansion.

The low β-cell proliferation rate during adulthood [9] could suggest that pericytes do not support β-cell proliferation after the neonatal period. Our analysis indicates that in culture, neonatal pericytes can stimulate adult β-cell proliferation. Thus, β-cells maintain their ability to respond to proliferative cues produced by pericytes even as they age. It is therefore possible that age-dependent changes in pancreatic pericytes affect their ability to promote β-cell proliferation beyond the neonatal period. Alternatively, physiological levels of pericytic components might be insufficient to drive adult β-cell proliferation in vivo.

β-cell mass is reduced in both Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes mellitus [9], [55]. Thus, β-cell regeneration and replacement represent attractive approaches for treating this disease. Since both approaches rely on cell proliferation, elucidating and harnessing the regulatory mechanism underlying physiological β-cell proliferation will facilitate establishing protocols for β-cell expansion. Here, we suggest a previously unappreciated role of a key component of the pancreas microenvironment, namely, pericytes, in neonatal β-cell replication. The findings of this study would therefore aid in developing improved protocols for β-cell expansion as a potential cure for diabetes.

Author contributions

A.E. designed and conducted experiments, and acquired and analyzed data. E.R. and L.S. conducted experiments and acquired data, S.M. and D.B. acquired and analyzed data. L.L. designed and supervised research, and wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Shimon Efrat (Tel Aviv University) for sharing the βTC-tet cell line, and Laura Malka-Khalifa and Helen Guez (Tel Aviv University) for critically reading the manuscript. This work was supported by European Research Council starting grant (336204; to L.L.).

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Georgia S., Bhushan A. Beta cell replication is the primary mechanism for maintaining postnatal beta cell mass. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2004;114(7):963–968. doi: 10.1172/JCI22098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gregg B.E., Moore P.C., Demozay D., Hall B.A., Li M., Husain A. Formation of a human β-cell population within pancreatic islets is set early in life. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2012;97(9):3197–3206. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Finegood D.T., Scaglia L., Bonner-Weir S. Dynamics of beta-cell mass in the growing rat pancreas. Estimation with a simple mathematical model. Diabetes. 1995;44(3):249–256. doi: 10.2337/diab.44.3.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Romer A.I., Sussel L. Pancreatic islet cell development and regeneration. Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Obesity. 2015;22(4):255–264. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herrera P.L. Adult insulin-and glucagon-producing cells differentiate from two independent cell lineages. Development (Cambridge, England) 2000;53(2):295–308. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.11.2317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dor Y., Brown J., Martinez O., Melton D. Adult pancreatic beta-cells are formed by self-duplication rather than stem-cell differentiation. Nature. 2004;429(6987):41–46. doi: 10.1038/nature02520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meier J.J., Butler A.E., Saisho Y., Monchamp T., Galasso R., Bhushan A. Beta-cell replication is the primary mechanism subserving the postnatal expansion of beta-cell mass in humans. Diabetes. 2008;57(6):1584–1594. doi: 10.2337/db07-1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chamberlain C.E., Scheel D.W., McGlynn K., Kim H., Miyatsuka T., Wang J. Menin determines K-RAS proliferative outputs in endocrine cells. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2014;124(9):4093–4101. doi: 10.1172/JCI69004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang P., Fiaschi-Taesch N.M., Vasavada R.C., Scott D.K., García-Ocaña A., Stewart A.F. Diabetes mellitus–advances and challenges in human β-cell proliferation. Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 2015;11(4):201–212. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2015.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen H., Gu X., Liu Y., Wang J., Wirt S.E., Bottino R. PDGF signalling controls age-dependent proliferation in pancreatic β-cells. Nature. 2011;478(7369):349–355. doi: 10.1038/nature10502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Teta M., Long S.Y., Wartschow L.M., Rankin M.M., Kushner J.A. Very slow turnover of beta-cells in aged adult mice. Diabetes. 2005;54(9):2557–2567. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.9.2557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonner-Weir S., Deery D., Leahy J.L., Weir G.C. Compensatory growth of pancreatic beta-cells in adult rats after short-term glucose infusion. Diabetes. 1989;38(1):49–53. doi: 10.2337/diab.38.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hahn von Dorsche H., Schäfer H., Titlbach M. Histophysiology of the obesity-diabetes syndrome in sand rats. Advances in Anatomy, Embryology, and Cell Biology. 1994;130:1–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sorenson R.L., Brelje T.C. Adaptation of islets of Langerhans to pregnancy: beta-cell growth, enhanced insulin secretion and the role of lactogenic hormones. Hormone and Metabolic Research. 1997;29(6):301–307. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-979040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stolovich-Rain M., Hija A., Grimsby J., Glaser B., Dor Y. Pancreatic beta cells in very old mice retain capacity for compensatory proliferation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2012;287(33):27407–27414. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.350736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ouaamari El A., Kawamori D., Dirice E., Liew C.W., Shadrach J.L., Hu J. Liver-derived systemic factors drive β cell hyperplasia in insulin-resistant states. Cell Reports. 2013;3(2):401–410. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim H., Toyofuku Y., Lynn F.C., Chak E., Uchida T., Mizukami H. Serotonin regulates pancreatic beta cell mass during pregnancy. Nature Medicine. 2010;16(7):804–808. doi: 10.1038/nm.2173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shirakawa J., Fernandez M., Takatani T., Ouaamari El A., Jungtrakoon P., Okawa E.R. Insulin signaling regulates the FoxM1/PLK1/CENP-a pathway to promote adaptive pancreatic β cell proliferation. Cell Metabolism. 2017;25(4) doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.02.004. 868–882.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moullé V.S., Vivot K., Tremblay C., Zarrouki B., Ghislain J., Poitout V. Glucose and fatty acids synergistically and reversibly promote beta cell proliferation in rats. Diabetologia. 2017;60(5):879–888. doi: 10.1007/s00125-016-4197-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nikolova G., Jabs N., Konstantinova I., Domogatskaya A., Tryggvason K., Sorokin L. The vascular basement membrane: a niche for insulin gene expression and beta cell proliferation. Developmental Cell. 2006;10(3):397–405. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brissova M., Aamodt K., Brahmachary P., Prasad N., Hong J.-Y., Dai C. Islet microenvironment, modulated by vascular endothelial growth factor-A signaling, promotes β cell regeneration. Cell Metabolism. 2014;19(3):498–511. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riley K.G., Pasek R.C., Maulis M.F., Dunn J.C., Bolus W.R., Kendall P.L. Macrophages are essential for CTGF-mediated adult β-cell proliferation after injury. Molecular Metabolism. 2015;4(8):584–591. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tarussio D., Metref S., Seyer P., Mounien L., Vallois D., Magnan C. Nervous glucose sensing regulates postnatal β cell proliferation and glucose homeostasis. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2013;124(1):413–424. doi: 10.1172/JCI69154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johansson M., Mattsson G., Andersson A., Jansson L., Carlsson P.-O. Islet endothelial cells and pancreatic beta-cell proliferation: studies in vitro and during pregnancy in adult rats. Endocrinology. 2006;147(5):2315–2324. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Richards O.C., Raines S.M., Attie A.D. The role of blood vessels, endothelial cells, and vascular pericytes in insulin secretion and peripheral insulin action. Endocrine Reviews. 2010;31(3):343–363. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kragl M., Lammert E. Basement membrane in pancreatic islet function. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 2010;654(Chapter 10):217–234. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-3271-3_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Armulik A., Genové G., Betsholtz C. Pericytes: developmental, physiological, and pathological perspectives, problems, and promises. Developmental Cell. 2011;21(2):193–215. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diaferia G.R., Jimenez-Caliani A.J., Ranjitkar P., Yang W., Hardiman G., Rhodes C.J. β1 integrin is a crucial regulator of pancreatic β-cell expansion. Development (Cambridge, England) 2013;140(16):3360–3372. doi: 10.1242/dev.098533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Golosow N., Grobstein C. Epitheliomesenchymal interaction in pancreatic morphogenesis. Developmental Biology. 1962;4:242–255. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(62)90042-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Otonkoski T., Cirulli V., Beattie M., Mally M.I., Soto G., Rubin J.S. A role for hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor in fetal mesenchyme-induced pancreatic beta-cell growth. Endocrinology. 1996;137(7):3131–3139. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.7.8770939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bhushan A., Itoh N., Kato S., Thiery J.P., Czernichow P., Bellusci S. Fgf10 is essential for maintaining the proliferative capacity of epithelial progenitor cells during early pancreatic organogenesis. Development (Cambridge, England) 2001;128(24):5109–5117. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.24.5109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Attali M., Stetsyuk V., Basmaciogullari A., Aiello V., Zanta-Boussif M.A., Duvillie B. Control of beta-cell differentiation by the pancreatic mesenchyme. Diabetes. 2007;56(5):1248–1258. doi: 10.2337/db06-1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Landsman L., Nijagal A., Whitchurch T.J., Vanderlaan R.L., Zimmer W.E., Mackenzie T.C. Pancreatic mesenchyme regulates epithelial organogenesis throughout development. PLoS Biology. 2011;9(9):e1001143. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guo T., Landsman L., Li N., Hebrok M. Factors expressed by murine embryonic pancreatic mesenchyme enhance generation of insulin-producing cells from hESCs. Diabetes. 2013;62(5):1581–1592. doi: 10.2337/db12-0167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sneddon J.B., Borowiak M., Melton D.A. Self-renewal of embryonic-stem-cell-derived progenitors by organ-matched mesenchyme. Nature. 2012;491(7426):765–768. doi: 10.1038/nature11463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sasson A., Rachi E., Sakhneny L., Baer D., Lisnyansky M., Epshtein A. Islet pericytes are required for β-cell maturity. Diabetes. 2016;65(10):3008–3014. doi: 10.2337/db16-0365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Efrat S., Fusco-DeMane D., Lemberg H., Emran al O., Wang X. Conditional transformation of a pancreatic beta-cell line derived from transgenic mice expressing a tetracycline-regulated oncogene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1995;92(8):3576–3580. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Buch T., Heppner F.L., Tertilt C., Heinen T.J.A.J., Kremer M., Wunderlich F.T. A Cre-inducible diphtheria toxin receptor mediates cell lineage ablation after toxin administration. Nature Methods. 2005;2(6):419–426. doi: 10.1038/nmeth762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Verzi M.P., Stanfel M.N., Moses K.A., Kim B.-M., Zhang Y., Schwartz R.J. Role of the homeodomain transcription factor Bapx1 in mouse distal stomach development. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(5):1701–1710. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Srinivas S., Watanabe T., Lin C.S., William C.M., Tanabe Y., Jessell T.M. Cre reporter strains produced by targeted insertion of EYFP and ECFP into the ROSA26 locus. BMC Developmental Biology. 2001;1:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Epshtein A., Sakhneny L., Landsman L. Isolating and analyzing cells of the pancreas mesenchyme by flow cytometry. Journal of Visualized Experiments. 2017;(119) doi: 10.3791/55344. e55344–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fleischer N., Chen C., Surana M., Leiser M., Rossetti L., Pralong W. Functional analysis of a conditionally transformed pancreatic beta-cell line. Diabetes. 1998;47(9):1419–1425. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.9.1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tribioli C., Lufkin T. Molecular cloning, chromosomal mapping and developmental expression of BAPX1, a novel human homeobox-containing gene homologous to Drosophila bagpipe. Gene. 1997;203(2):225–233. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00520-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hecksher-Sørensen J., Watson R.P., Lettice L.A., Serup P., Eley L., De Angelis C. The splanchnic mesodermal plate directs spleen and pancreatic laterality, and is regulated by Bapx1/Nkx3.2. Development (Cambridge, England) 2004;131(19):4665–4675. doi: 10.1242/dev.01364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Milo-Landesman D., Efrat S. Growth factor-dependent proliferation of the pancreatic beta-cell line betaTC-tet: an assay for beta-cell mitogenic factors. International Journal of Experimental Diabetes Research. 2002;3(1):69–74. doi: 10.1080/15604280212526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Parnaud G., Bosco D., Berney T., Pattou F., Kerr-Conte J., Donath M.Y. Proliferation of sorted human and rat beta cells. Diabetologia. 2008;51(1):91–100. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0855-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Banerjee M., Virtanen I., Palgi J., Korsgren O., Otonkoski T. Proliferation and plasticity of human beta cells on physiologically occurring laminin isoforms. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2012;355(1):78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2012.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saito M., Iwawaki T., Taya C., Yonekawa H., Noda M., Inui Y. Diphtheria toxin receptor-mediated conditional and targeted cell ablation in transgenic mice. Nature Biotechnology. 2001;19(8):746–750. doi: 10.1038/90795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jung S., Unutmaz D., Wong P., Sano G.-I., De los Santos K., Sparwasser T. In vivo depletion of CD11c+ dendritic cells abrogates priming of CD8+ T cells by exogenous cell-associated antigens. Immunity. 2002;17(2):211–220. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00365-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tribioli C., Frasch M., Lufkin T. Bapx1: an evolutionary conserved homologue of the Drosophila bagpipe homeobox gene is expressed in splanchnic mesoderm and the embryonic skeleton. Mechanisms of Development. 1997;65(1–2):145–162. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(97)00067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Russ H.A., Landsman L., Moss C.L., Higdon R., Greer R.L., Kaihara K. Dynamic proteomic analysis of pancreatic mesenchyme reveals novel factors that enhance human embryonic stem cell to pancreatic cell differentiation. Stem Cells International. 2016:6183562. doi: 10.1155/2016/6183562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vasavada R.C., Gonzalez-Pertusa J.A., Fujinaka Y., Fiaschi-Taesch N., Cozar-Castellano I., García-Ocaña A. Growth factors and beta cell replication. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 2006;38(5–6):931–950. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Crisera C.A., Kadison A.S., Breslow G.D., Maldonado T.S., Longaker M.T., Gittes G.K. Expression and role of laminin-1 in mouse pancreatic organogenesis. Diabetes. 2000;49(6):936–944. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.6.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Boerner B.P., George N.M., Targy N.M., Sarvetnick N.E. Tgf-beta superfamily member nodal stimulates human beta-cell proliferation while maintaining cellular viability. Endocrinology. 2013;154(11):4099–4112. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Saunders D., Powers A.C. Replicative capacity of β-cells and type 1 diabetes. Journal of Autoimmunity. 2016;71:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2016.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]