Abstract

Protein degradation technology based on hybrid small molecules is an emerging drug modality that has significant potential in drug discovery and as a unique method of post-translational protein knockdown in the field of chemical biology. Here, we report the first example of a novel and potent protein degradation inducer that binds to an allosteric site of the oncogenic BCR-ABL protein. BCR-ABL allosteric ligands were incorporated into the SNIPER (Specific and Nongenetic inhibitor of apoptosis protein [IAP]-dependent Protein Erasers) platform, and a series of in vitro biological assays of binding affinity, target protein modulation, signal transduction, and growth inhibition were carried out. One of the designed compounds, 6 (SNIPER(ABL)-062), showed desirable binding affinities against ABL1, cIAP1/2, and XIAP and consequently caused potent BCR-ABL degradation.

Keywords: BCR-ABL, allosteric, protein degradation, SNIPER, E3 ubiquitin ligase, IAP

Molecular target therapies against chronic myelogenous lymphoma (CML) have been developed successfully by targeting BCR-ABL, a key oncoprotein required for proliferation of CML cells.1,2 BCR-ABL is a constitutively active tyrosine kinase generated by chromosomal translocation of the ABL gene from chromosome 9 to the BCR gene on chromosome 22, which leads to activation of downstream signaling and thus causes unregulated proliferation of CML cells in patients. Pharmaceutical researchers have focused on discovering ATP-competitive inhibitors against the ABL tyrosine kinase of BCR-ABL to treat CML. As a result, several BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have been identified and approved for CML treatment. Those include a first-generation TKI, imatinib; second-generation TKIs, dasatinib/nilotinib; and a third-generation TKI, ponatinib.3

Development of small molecule inhibitors has long been a promising strategy for drug discovery in pharmaceutical industries. In this regard, we have developed a novel drug discovery platform based on protein degradation using hybrid small molecules named specific and nongenetic inhibitor of apoptosis protein [IAP]-dependent protein erasers (SNIPERs).4−15 SNIPERs possess two distinct ligand moieties, i.e., one for the protein of interest (POI) and the other for IAP, which are covalently linked to give a single molecule. In cells, IAP proteins that bind to SNIPERs would functionally work as E3 ubiquitin ligases and promote ubiquitination of the POI tethered at the other end of the SNIPER molecule, which results in selective protein degradation of the POI by the proteasome.

Conceptually, SNIPERs and proteolysis targeting chimeras (PROTACs) share a mechanism for POI degradation. SNIPERs recruit IAPs to POIs, whereas PROTACs recruit several E3 ubiquitin ligases such as MDM2, von Hippel-Lindau, and Cereblon.16 Currently, several drug target proteins, e.g., androgen receptor,15,17,18 estrogen receptor,6,12,19 and bromodomain containing 4,20−25 have been degraded effectively via the ubiquitin–proteasome system (UPS) using SNIPER and/or PROTAC platforms. During the course of the development, protein degradation of BCR-ABL has also been accomplished recently by several research groups.10,14,26

To induce target protein degradation, SNIPERs and PROTACs require a ligand moiety that has binding affinity to a POI. Most of the previous works have focused on introducing orthosteric POI ligands into hybrid molecules. In contrast, few studies are available where nonorthosteric POI ligands have been used without showing potent protein degradation activities.16,27 In this study, we describe the potential of SNIPERs to bind allosterically to the oncogenic BCR-ABL protein in order to further expand the capability of protein degradation technology.

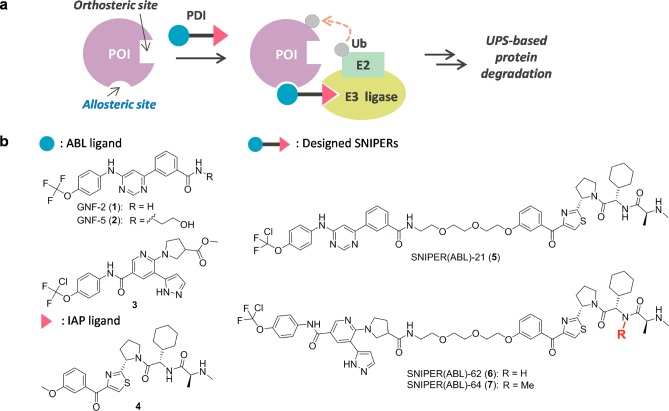

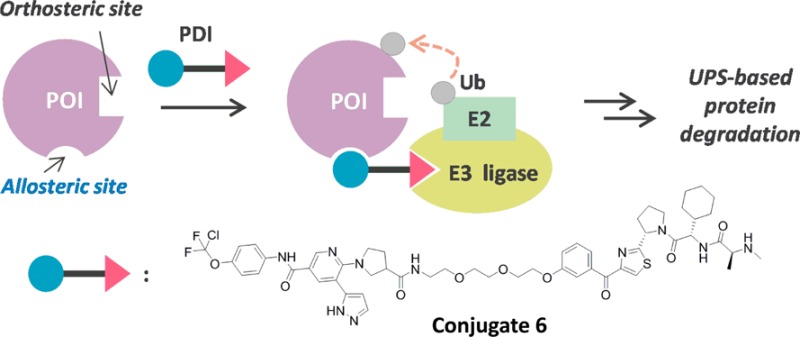

Figure 1a illustrates the general concept of our current study: a protein degradation inducer (PDI), i.e., designed SNIPER, binds both to E3 ubiquitin ligase and allosterically to a POI in situ, which results in (i) ternary complex formation among them; (ii) ubiquitination of the POI; and (iii) protein degradation of the POI via the UPS. For targeted BCR-ABL degradation, we selected GNF-2/-5 (1–2)28 and ABL001 derivative 3(29,30) for BCR-ABL allosteric ligand moieties, and LCL-161 derivative 4(12,14,15) for the IAP ligand moiety (Figure 1b). Using structural information on ABL in complex with 1 (PDB ID: 3K5V), we envisaged a suitable vector for linker attachment in all BCR-ABL ligands. Moreover, the methoxy group in IAP ligand 4 was recognized as a practical linker attachment portion based on previous studies.12,14,15 Thus, we designed 5 (SNIPER(ABL)-21) and 6 (SNIPER(ABL)-62). In addition, 7 (SNIPER(ABL)-64) was designed as a negative control of 6 that cannot recruit IAPs because of negligible binding affinity. All compounds used in the current work were prepared newly or according to literature. The synthetic procedures are described in the Supporting Information.

Figure 1.

(a) Brief illustration of protein degradation exploiting an allosteric site of the POI. (b) Chemical structures of ABL ligands 1–3, IAP ligand 4, and the designed conjugates 5–7.

Table 1 summarizes the binding affinity of parent ligands alone and the designed SNIPER molecules to ABL1 (allosteric site), cIAP1, cIAP2, and XIAP, determined by a time-resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer (TR-FRET) based binding assay. In general, binding affinities were observed to decrease slightly after chemical conjugation. As for binding affinity to ABL1, compound 3 and its conjugates 6 and 7 showed higher affinity than GNF-2-related compounds 1, 2, and 5, according to the binding affinity of the ABL ligands. Conjugates 5 and 6 retained the binding affinity to IAPs as well, whereas the negative control 7 lost the affinity entirely.

Table 1. Results of TR-FRET Based Binding Assay for ABL1 (Allosteric Site), cIAP1/2, and XIAPa.

| compd | ABL1 IC50 (nM) | cIAP1 IC50 (nM) | cIAP2 IC50 (nM) | XIAP IC50 (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (GNF-2) | 2800 (2000–4000) | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 2 (GNF-5) | 2000 (1400–2900) | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 3 (ABL001 derivative) | 35 (27–45) | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 4 (LCL-161 derivative) | n.d. | 4.8 (4.3–5.4) | 5.7 (4.3–7.5) | 67 (49–96) |

| 5 (SNIPER(ABL)-21) | 2000 (1200–3300) | 220 (180–280) | 330 (220–500) | 94 (70–130) |

| 6 (SNIPER(ABL)-62) | 360 (220–590) | 86 (78–94) | 140 (120–160) | 120 (99–140) |

| 7 (SNIPER(ABL)-64) | 340 (210–570) | >1000 | >1000 | >1000 |

The inhibitory activity of the test compounds at several concentrations were examined as described in Supporting Information. IC50 values and 95% confidence intervals were calculated by nonlinear regression analysis of percent inhibition data (n ≥ 3). n.d.: not determined.

Figure 2 illustrates a pairwise comparison of the in vitro protein degradation activity of conjugates 5 and 6 in K562 cells after 6 h incubation. Conjugate 6 showed effective degradation of BCR-ABL from 30 nM and a maximum activity at 100–300 nM, whereas conjugate 5 showed degradation at ≥5000 nM. These differences could be simply derived from superior binding affinity profiles of 6, though physicochemical properties of 5 and 6 should be taken into consideration for discussion of the cell-based assay. In addition to the BCR-ABL protein, SNIPER molecules reduced the level of cIAP1 protein, which was possibly evoked via autoubiquitination, induced by the binding of IAP ligand moiety to cIAP1.12,14,15 Complementarily, the combination of the ABL ligand (2 or 3) and the IAP ligand 4 alone did not effectively decrease the level of BCR-ABL protein at concentrations where protein degradation was observed by SNIPER molecules, indicating the functional effect of SNIPERs as protein degradation inducers. In addition, conjugate 6 showed a bell-shaped curve trend, i.e., the hook effect, in its degradation activity, suggesting the formation of a ternary complex among BCR-ABL, the SNIPER molecule, and IAP for degradation.31

Figure 2.

Conjugate 6 shows potent protein knockdown activity. K562 cells were incubated with the indicated concentration of conjugates 5, 6, or ligand mix (ABL ligand 2 or 3 plus IAP ligand 4) for 6 h. Numbers below the ABL panel represent the BCR-ABL/β-actin ratio normalized by the vehicle control as 100. Data in the bar graph are means ± standard deviation (n = 3).

The mechanism of target protein degradation induced by conjugate 6 was further investigated in K562 cells (Figure 3). First, we examined the effect of a UPS inhibitor. As shown previously,14 a proteasome inhibitor, benzyl N-((2S)-4-methyl-1-(((2S)-4-methyl-1-(((2S)-4-methyl-1-oxopentan-2-yl)amino)-1-oxopentan-2-yl)amino)-1-oxopentan-2-yl)carbamate (MG132),32 reduced the level of the BCR-ABL protein (data not shown). Therefore, a ubiquitin-activating enzyme inhibitor, methyl N-((1S,2R,3S,4R)-2,3-dihydroxy-4-((2-(3-(trifluoromethylsulfanyl)phenyl)pyrazolo(1,5-a)pyrimidin-7-yl)amino)cyclopentyl)sulfamate 23 (MLN 7243),33 was used as another UPS inhibitor. The targeted degradation of BCR-ABL by conjugate 6 was canceled by the inhibitor 23, suggesting that the ubiquitin system is essential for BCR-ABL protein degradation (Figure 3a). The requirement of IAP binding for protein degradation was demonstrated by two independent biological experiments as follows. The pairwise comparison of conjugate 6 and its negative control 7 indicated that the IAP binding moiety within the molecule is necessary (Figure 3b). Similarly, a competition assay using an excess amount of IAP ligand 4 (10 μM) diminished the protein degradation ability of conjugate 6 (Figure 3c).

Figure 3.

Involvement of ubiquitin and IAPs in conjugate 6-induced reduction of BCR-ABL protein. (a) Effect of an inhibitor of ubiquitin activating enzyme 23 on protein knockdown activity of conjugate 6 in K562 cells. Cells were incubated with 100 nM conjugate 6 and/or 10 μM inhibitor 23 for 6 h. (b) IAP binding ability of conjugate 6 is necessary for protein knockdown activity. K562 cells were incubated with 100 nM conjugate 6 or 7 for 6 h. (c) Competition assay using excess amount of IAP ligand 4 with conjugate 6 in K562 cells. Cells were incubated with 100 nM conjugate 6 and/or 10 μM IAP ligand 4 for 6 h. Numbers below the ABL panel represent the BCR-ABL/β-actin ratio normalized by the vehicle control as 100. Data in the bar graph are means ± standard deviation (n = 3).

Conjugate 6 is designed to recruit IAPs for degradation of the BCR-ABL protein. To understand which IAPs are involved in the degradation of BCR-ABL by conjugate 6, we down-regulated IAPs by shRNA-mediated gene silencing. Among IAP family members, we focused on XIAP and cIAP1 since cIAP2 is not detectable in K562 cells. Silencing of cIAP1 expression significantly suppressed the conjugate 6-induced BCR-ABL protein degradation, while silencing of XIAP expression alone did not affect the degradation (Figure S1). These results suggest that cIAP1 play a major role on the degradation of BCR-ABL protein when treated with conjugate 6.

Given the degradation of cIAP1 by conjugate 6 (Figure 2) and the cIAP1 as the primary ubiquitin ligase responsible for the conjugate 6-induced BCR-ABL degradation (Figure S1), one can ask how cIAP1 is recruited to BCR-ABL protein. To address this issue, K562 cells were pretreated with IAP ligand 4 to degrade cIAP1 protein that exists in the cells, and then the cells were further treated with conjugate 6. The result shows that the pretreatment with the IAP ligand 4 only slightly suppressed the conjugate 6-induced degradation of BCR-ABL protein (Figure S2). This could be explained by the recruitment of freshly synthesized cIAP1 protein to the BCR-ABL because de novo synthesis of the cIAP1 protein was not inhibited in this experiment, which contrasted with the shRNA-mediated silencing of cIAP1. cIAP1 is a protein with a half-life of approximately 5 h,34 but cells accumulate a significant amount of cIAP1 protein, indicating that a substantial amount of cIAP1 protein is constantly synthesized in the cells, which supports this model. Probably, a binary complex composed of BCR-ABL and conjugate 6 is formed first, and then freshly synthesized cIAP1 is recruited to the complex, which triggers the ubiquitination and degradation of both BCR-ABL and cIAP1 proteins. Thus, we think conjugate 6 continuously induces the degradation of BCR-ABL protein as far as cIAP1 is synthesized in the cells.

In CML, such as K562 cells, the constitutively active tyrosine kinase of BCR-ABL promotes uncontrolled cell proliferation via up-regulation of STAT5 (signal transducer and activator of transcription 5) and CrkL (Crk like proto-oncogene) signaling pathways. Therefore, the effect of conjugate 6 on the BCR-ABL signaling pathways was evaluated along with ABL ligand 3 as a control. Significantly, both compounds reduced the phosphorylation of BCR-ABL and the BCR-ABL substrates STAT5 and CrkL (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Conjugate 6 inhibits the BCR-ABL signaling pathway. K562 cells were incubated with 100 nM conjugate 6 or ABL ligand 3 for 6 h. pBCR-ABL, pSTAT5, and pCrkL stand for phosphorylated BCR-ABL, STAT5, and CrkL, respectively.

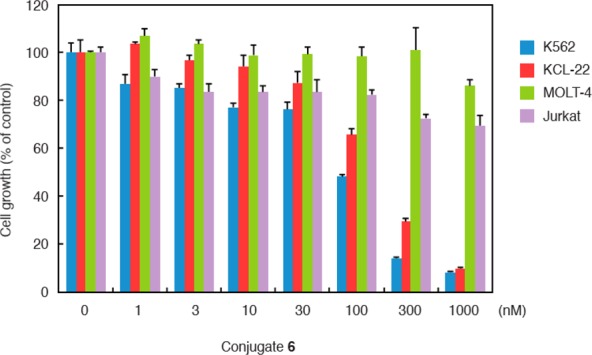

Consistent with the degradation of the BCR-ABL protein and the inhibition of BCR-ABL-mediated signaling pathways, conjugate 6 dramatically inhibited the growth of K562 cells at ≥100 nM (Figure 5). A similar growth inhibitory effect and protein degradation activity of conjugate 6 were also observed in another CML cell line, KCL-22, expressing BCR-ABL (Figures 5 and S3). Conjugate 6 did not inhibit the growth of leukemia cell lines, MOLT-4 and Jurkat, which do not express BCR-ABL. As a control experiment, we also used the IAP ligand 4 and found no growth inhibition of K562 cells by this compound (Figure S4). These data indicate that conjugate 6 induces the degradation of BCR-ABL protein, which results in the inhibition of BCR-ABL-mediated signaling pathways and CML proliferation in cells expressing BCR-ABL.

Figure 5.

Conjugate 6 inhibits proliferation of CML cells expressing BCR-ABL. Cells were incubated with the indicated concentration of 6 for 48 h. Data in the bar graph are means ± standard deviation (n = 3).

In summary, novel and potent SNIPER molecules that bind to the allosteric site of BCR-ABL were designed, synthesized, and assessed in various biological experiments. The results presented herein indicate the potential use of ligands that bind to nonorthosteric sites of target proteins and consequently expand the capability of protein knockdown technology. Further studies on SNIPER molecules discussed in this report and basic research on our protein knockdown technology are ongoing.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mariko Seki for measurement of the protein knockdown activities.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- BCR

breakpoint cluster region

- ABL

Abelson murine leukemia viral oncogene homolog

- SNIPER

Specific and Nongenetic IAP-dependent Protein Eraser

- cIAP1

cellular inhibitor of apoptosis protein 1

- XIAP

X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein

- CML

chronic myelogenous leukemia

- TKIs

tyrosine kinase inhibitors

- UPS

ubiquitin proteasome system

- POI

protein of interest

- PROTACs

proteolysis targeting chimeras

- PDI

protein degradation inducer

- TR-FRET

time-resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer

- STAT5

signal transducer and activator of transcription 5

- CrkL

Crk like proto-oncogene

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.7b00247.

Synthetic procedures for all compounds listed, the analysis of the mechanism of conjugate 6-induced reduction of the BCR-ABL protein, the protein knockdown activity of conjugate 6 in KCL-22 cells, the effect of IAP ligand 4 on K562 cell proliferation, and the protocols for in vitro assays (binding assay, protein degradation assay, and proliferation assay) (PDF)

Author Contributions

¶ K.S. and N.S. contributed equally.

This study was supported, in part, by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (KAKENHI Grant Numbers 26860050 to N.S., 26860049 to N.O., 16H05090 to T.H. and M.N., and 16K15121 to N.O. and M.N.), by the Project for Cancer Research And Therapeutic Evolution (P-CREATE) (16cm0106522j0001 and 17cm0106522j0002 to N.S.; 16cm0106124j0001 and 17cm0106124j0002 to N.O.), and the Research on Development of New Drugs (15ak0101029h1402 and 16ak0101029j1403 to M.N.) from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED), by the Ministry of Health and Labor Welfare, Japan (to M.N.), by Takeda Science Foundation (to N.O.), and by Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. (to M.N.).

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): K.S., T.S., N.M., O.U., H.N., and N.C. are employees of Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Osaka, Japan). M.N. received research funding from Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Quintas-Cardama A.; Kantarjian H.; Cortes J. Flying under the radar: the new wave of BCR-ABL inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2007, 6 (10), 834–848. 10.1038/nrd2324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintas-Cardama A.; Cortes J. Molecular biology of bcr-abl1-positive chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood 2009, 113 (8), 1619–1630. 10.1182/blood-2008-03-144790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy E. P.; Aggarwal A. K. The ins and outs of bcr-abl inhibition. Genes Cancer 2012, 3 (5–6), 447–454. 10.1177/1947601912462126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh Y.; Ishikawa M.; Naito M.; Hashimoto Y. Protein knockdown using methyl bestatin-ligand hybrid molecules: design and synthesis of inducers of ubiquitination-mediated degradation of cellular retinoic acid-binding proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132 (16), 5820–5826. 10.1021/ja100691p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuhira K.; Ohoka N.; Sai K.; Nishimaki-Mogami T.; Itoh Y.; Ishikawa M.; Hashimoto Y.; Naito M. Specific degradation of CRABP-II via cIAP1-mediated ubiquitylation induced by hybrid molecules that crosslink cIAP1 and the target protein. FEBS Lett. 2011, 585 (8), 1147–1152. 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuhira K.; Demizu Y.; Hattori T.; Ohoka N.; Shibata N.; Nishimaki-Mogami T.; Okuda H.; Kurihara M.; Naito M. Development of hybrid small molecules that induce degradation of estrogen receptor-alpha and necrotic cell death in breast cancer cells. Cancer Sci. 2013, 104 (11), 1492–1498. 10.1111/cas.12272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohoka N.; Nagai K.; Hattori T.; Okuhira K.; Shibata N.; Cho N.; Naito M. Cancer cell death induced by novel small molecules degrading the TACC3 protein via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2014, 5, e1513. 10.1038/cddis.2014.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohoka N.; Shibata N.; Hattori T.; Naito M. Protein knockdown technology: application of ubiquitin ligase to cancer therapy. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2016, 16 (2), 136–146. 10.2174/1568009616666151112122502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuhira K.; Demizu Y.; Hattori T.; Ohoka N.; Shibata N.; Kurihara M.; Naito M. Molecular Design, Synthesis, and Evaluation of SNIPER(ER) That Induces Proteasomal Degradation of ERalpha. Methods Mol. Biol. 2016, 1366, 549–560. 10.1007/978-1-4939-3127-9_42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demizu Y.; Shibata N.; Hattori T.; Ohoka N.; Motoi H.; Misawa T.; Shoda T.; Naito M.; Kurihara M. Development of BCR-ABL degradation inducers via the conjugation of an imatinib derivative and a cIAP1 ligand. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26 (20), 4865–4869. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuhira K.; Shoda T.; Omura R.; Ohoka N.; Hattori T.; Shibata N.; Demizu Y.; Sugihara R.; Ichino A.; Kawahara H.; Itoh Y.; Ishikawa M.; Hashimoto Y.; Kurihara M.; Itoh S.; Saito H.; Naito M. Targeted Degradation of Proteins Localized in Subcellular Compartments by Hybrid Small Molecules. Mol. Pharmacol. 2017, 91 (3), 159–166. 10.1124/mol.116.105569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohoka N.; Okuhira K.; Ito M.; Nagai K.; Shibata N.; Hattori T.; Ujikawa O.; Shimokawa K.; Sano O.; Koyama R.; Fujita H.; Teratani M.; Matsumoto H.; Imaeda Y.; Nara H.; Cho N.; Naito M. In vivo knockdown of pathogenic proteins via specific and nongenetic inhibitor of apoptosis protein (IAP)-dependent protein erasers (SNIPERs). J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292 (11), 4556–4570. 10.1074/jbc.M116.768853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohoka N.; Nagai K.; Shibata N.; Hattori T.; Nara H.; Cho N.; Naito M. SNIPER(TACC3) induces cytoplasmic vacuolization and sensitizes cancer cells to Bortezomib. Cancer Sci. 2017, 108 (5), 1032–1041. 10.1111/cas.13198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata N.; Miyamoto N.; Nagai K.; Shimokawa K.; Sameshima T.; Ohoka N.; Hattori T.; Imaeda Y.; Nara H.; Cho N.; Naito M. Development of protein degradation inducers of oncogenic BCR-ABL protein by conjugation of ABL kinase inhibitors and IAP ligands. Cancer Sci. 2017, 108 (8), 1657–1666. 10.1111/cas.13284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata N.; Nagai K.; Morita Y.; Ujikawa O.; Ohoka N.; Hattori T.; Koyama R.; Sano O.; Imaeda Y.; Nara H.; Cho N.; Naito M. Development of protein degradation inducers of androgen receptor by conjugation of androgen receptor ligands and inhibitor of apoptosis protein (IAP) ligands. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b00168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai A. C.; Crews C. M. Induced protein degradation: an emerging drug discovery paradigm. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2017, 16 (2), 101–114. 10.1038/nrd.2016.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneekloth J. S. Jr.; Fonseca F. N.; Koldobskiy M.; Mandal A.; Deshaies R.; Sakamoto K.; Crews C. M. Chemical genetic control of protein levels: selective in vivo targeted degradation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126 (12), 3748–3754. 10.1021/ja039025z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneekloth A. R.; Pucheault M.; Tae H. S.; Crews C. M. Targeted intracellular protein degradation induced by a small molecule: En route to chemical proteomics. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008, 18 (22), 5904–5908. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.07.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto K. M.; Kim K. B.; Verma R.; Ransick A.; Stein B.; Crews C. M.; Deshaies R. J. Development of Protacs to target cancer-promoting proteins for ubiquitination and degradation. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2003, 2 (12), 1350–1358. 10.1074/mcp.T300009-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J.; Qian Y.; Altieri M.; Dong H.; Wang J.; Raina K.; Hines J.; Winkler J. D.; Crew A. P.; Coleman K.; Crews C. M. Hijacking the E3 ubiquitin ligase Cereblon to efficiently target BRD4. Chem. Biol. 2015, 22 (6), 755–763. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2015.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter G. E.; Buckley D. L.; Paulk J.; Roberts J. M.; Souza A.; Dhe-Paganon S.; Bradner J. E. Phthalimide conjugation as a strategy for in vivo target protein degradation. Science 2015, 348 (6241), 1376–1381. 10.1126/science.aab1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zengerle M.; Chan K. H.; Ciulli A. Selective Small Molecule Induced Degradation of the BET Bromodomain Protein BRD4. ACS Chem. Biol. 2015, 10 (8), 1770–1777. 10.1021/acschembio.5b00216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadd M. S.; Testa A.; Lucas X.; Chan K. H.; Chen W.; Lamont D. J.; Zengerle M.; Ciulli A. Structural basis of PROTAC cooperative recognition for selective protein degradation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017, 13 (5), 514–521. 10.1038/nchembio.2329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou B.; Hu J.; Xu F.; Chen Z.; Bai L.; Fernandez-Salas E.; Lin M.; Liu L.; Yang C. Y.; Zhao Y.; McEachern D.; Przybranowski S.; Wen B.; Sun D.; Wang S. Discovery of a Small-Molecule Degrader of Bromodomain and Extra-Terminal (BET) Proteins with Picomolar Cellular Potencies and Capable of Achieving Tumor Regression. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan K. H.; Zengerle M.; Testa A.; Ciulli A. Impact of Target Warhead and Linkage Vector on Inducing Protein Degradation: Comparison of Bromodomain and Extra-Terminal (BET) Degraders Derived from Triazolodiazepine (JQ1) and Tetrahydroquinoline (I-BET726) BET Inhibitor Scaffolds. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai A. C.; Toure M.; Hellerschmied D.; Salami J.; Jaime-Figueroa S.; Ko E.; Hines J.; Crews C. M. Modular PROTAC design for the degradation of oncogenic BCR-ABL. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55 (2), 807–810. 10.1002/anie.201507634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henning R. K.; Varghese J. O.; Das S.; Nag A.; Tang G.; Tang K.; Sutherland A. M.; Heath J. R. Degradation of Akt using protein-catalyzed capture agents. J. Pept. Sci. 2016, 22 (4), 196–200. 10.1002/psc.2858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.; Adrian F. J.; Jahnke W.; Cowan-Jacob S. W.; Li A. G.; Iacob R. E.; Sim T.; Powers J.; Dierks C.; Sun F.; Guo G. R.; Ding Q.; Okram B.; Choi Y.; Wojciechowski A.; Deng X.; Liu G.; Fendrich G.; Strauss A.; Vajpai N.; Grzesiek S.; Tuntland T.; Liu Y.; Bursulaya B.; Azam M.; Manley P. W.; Engen J. R.; Daley G. Q.; Warmuth M.; Gray N. S. Targeting Bcr-Abl by combining allosteric with ATP-binding-site inhibitors. Nature 2010, 463 (7280), 501–506. 10.1038/nature08675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd S. K.; Furet P.; Grotzfeld R. M.; Jones D. B.; Manley P.; Marzinzik A.; Pelle X. F. A.; Salem B.; Schoepfer J. Benzamide derivatives for inhibiting the activity of ABL1, ABL2 and BCR-ABL1. WO/2013/171639, November 21, 2013.

- Wylie A. A.; Schoepfer J.; Jahnke W.; Cowan-Jacob S. W.; Loo A.; Furet P.; Marzinzik A. L.; Pelle X.; Donovan J.; Zhu W.; Buonamici S.; Hassan A. Q.; Lombardo F.; Iyer V.; Palmer M.; Berellini G.; Dodd S.; Thohan S.; Bitter H.; Branford S.; Ross D. M.; Hughes T. P.; Petruzzelli L.; Vanasse K. G.; Warmuth M.; Hofmann F.; Keen N. J.; Sellers W. R. The allosteric inhibitor ABL001 enables dual targeting of BCR-ABL1. Nature 2017, 543 (7647), 733–737. 10.1038/nature21702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglass E. F. Jr.; Miller C. J.; Sparer G.; Shapiro H.; Spiegel D. A. A comprehensive mathematical model for three-body binding equilibria. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135 (16), 6092–6099. 10.1021/ja311795d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsubuki S.; Kawasaki H.; Saito Y.; Miyashita N.; Inomata M.; Kawashima S. Purification and characterization of a Z-Leu-Leu-Leu-MCA degrading protease expected to regulate neurite formation: a novel catalytic activity in proteasome. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1993, 196 (3), 1195–1201. 10.1006/bbrc.1993.2378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afroze R.; Bharathan I. T.; Ciavarri J. P.; Fleming P. E.; Gaulin J. L.; Girard M.; Langston S. P.; Soucy F. R.; Wong T. T.; Ye Y. Pyrazolopyrimidinyl inhibitors of ubiquitin-activating enzyme. WO2013123169 A1, August 22, 2013.

- Lopez J.; John S. W.; Tenev T.; Rautureau G. J.; Hinds M. G.; Francalanci F.; Wilson R.; Broemer M.; Santoro M. M.; Day C. L.; Meier P. CARD-mediated autoinhibition of cIAP1’s E3 ligase activity suppresses cell proliferation and migration. Mol. Cell 2011, 42 (5), 569–583. 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.