Abstract

Background

A recent open-label pilot study (N=15) found that two to three moderate to high doses (20 and 30 mg/70 kg) of the serotonin 2A receptor agonist psilocybin, in combination with cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for smoking cessation, resulted in substantially higher 6-month smoking abstinence rates than are typically observed with other medications or CBT alone.

Objectives

To assess long-term effects of a psilocybin-facilitated smoking cessation program at ≥12 months after psilocybin administration.

Methods

The present report describes biologically verified smoking abstinence outcomes of the previous pilot study at ≥12 months, and related data on subjective effects of psilocybin.

Results

All 15 participants completed a 12-month follow-up, and 12 (80%) returned for a long-term (≥16 months) follow-up, with a mean interval of 30 months (range = 16 – 57 months) between target-quit date (i.e., first psilocybin session) and long-term follow-up. At 12-month follow-up, 10 participants (67%) were confirmed as smoking abstinent. At long-term follow-up, nine participants (60%) were confirmed as smoking abstinent. At 12-month follow-up 13 participants (86.7%) rated their psilocybin experiences among the 5 most personally meaningful and spiritually significant experiences of their lives.

Conclusion

These results suggest that in the context of a structured treatment program, psilocybin holds considerable promise in promoting long-term smoking abstinence. The present study adds to recent and historical evidence suggesting high success rates when using classic psychedelics in the treatment of addiction. Further research investigating psilocybin-facilitated treatment of substance use disorders is warranted.

Keywords: hallucinogen, tobacco, smoking cessation, nicotine, addiction, psilocybin, psychedelic, mystical experience, spirituality

Introduction

With almost 6 million tobacco-related deaths per year worldwide, and that number projected to rise to an estimated 8 million annual mortalities by 2030, smoking remains among the leading public health concerns of the 21st century (1). At present, the most successful available smoking cessation treatments fail to promote long-term abstinence in the majority of individuals who use them (2,3), underscoring an urgent need to explore innovative treatment approaches.

The authors recently reported on a novel intervention for smoking cessation combining two to three administrations of psilocybin, a naturally occurring serotonin 2A receptor (5-HT2AR) agonist, with cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). Initial results showed that 80% of participants in this open-label pilot-study (N=15) were biologically verified as smoking abstinent at the 6-month follow-up (4). Pilot results demonstrated safety and feasibility in this sample, with physiological adverse effects limited to mild post-session headache, and modest acute elevations in blood pressure and heart rate (4). Six volunteers (40%) reported acute challenging (i.e., fearful, anxiety-provoking) psilocybin session experiences. However, these effects resolved by the end of drug session days via interpersonal support from study staff, without pharmacologic intervention or persisting deleterious sequelae (4). The current report presents long-term follow-up data from this trial, including abstinence outcomes at 12 months and an average of 30 months post-treatment, as well as data on persisting psychological effects at 12-month follow-up.

Methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, and all participants provided informed consent. Participants were 15 smokers (10 males) without histories of severe mental illness, with a mean age of 51 years, who smoked on average 19 cigarettes per day (CPD) for a mean of 31 years at screening, with a mean of 6 previous quit attempts. Participants underwent a 15-week combination treatment consisting of four weekly preparatory meetings integrating CBT, elements of mindfulness training, and guided imagery for smoking cessation. Participants received a moderate (20 mg/70 kg) dose of psilocybin in week 5 of treatment, which served as the Target-Quit Date (TQD), and a high dose of psilocybin (30 mg/70 kg) approximately 2 weeks later. Participants had the opportunity to participate in a third, optional high-dose psilocybin session in week 13 of study treatment.

For 10 weeks following the TQD, participants returned to the laboratory to provide breath and urine samples to test for recent smoking, complete self-report questionnaires, and meet with study staff. Participants returned for follow-up meetings at 6 and 12 months post-TQD, and were later invited back for a retrospective interview probing potential mechanisms of the study treatment at a mean of 30 months post-TQD. For a detailed description of the study sample and intervention see Johnson et al. (4). The current report presents previously unpublished data regarding smoking cessation outcomes at the 12-month and long-term follow-ups.

Measures

Smoking Biomarkers

Biomarkers of recent smoking were used to assess participants’ smoking status at 12-month and long-term follow-ups. Breath carbon monoxide (CO) was measured using a Bedfont Micro+ Smokerlyzer (Haddonfield, NJ). Urine samples were collected and sent to an independent laboratory (Friends Medical Laboratory, Baltimore, MD) for analysis of cotinine, a metabolite of nicotine.

Timeline Follow-back (TLFB)

Using the TLFB, a widely used retrospective measure of substance use (5), participants provided self-reported estimates of their daily cigarette consumption in the 30 days prior to beginning the study treatment. On all subsequent visits participants self-reported daily cigarette consumption since the last laboratory visit using the TLFB. Therefore, the TLFB provided continuous daily data on cigarette consumption.

Persisting Effects Questionnaire

Participants completed a 143-item questionnaire designed to measure persisting changes in attitudes, moods, behavior, and spirituality attributed to their most recent psilocybin experience one week after each psilocybin session. A retrospective version of this questionnaire was administered at the 12-month follow-up asking participants to respond regarding their cumulative psilocybin session experiences.

This questionnaire has previously been used to assess intermediate and long-term effects of psilocybin (6–8). The initial 140 items are rated on a 6-point scale ranging from 0 (none) to 5 (extreme) assessing positive and negative changes in six categories: Attitudes about life (26 items); Attitudes about self (22 items); Mood changes (18 items); Relationships (18 items); Behavioral changes (two items); and Spirituality (43 items). Additionally, this questionnaire included three items asking participants to rate: 1) the overall personal meaning, 2) spiritual significance, and 3) effects on well-being or life satisfaction attributed to psilocybin experiences or contemplation of those experiences.

Mystical Experience Questionnaire (MEQ30)

The MEQ30 is a validated 30-item scale designed to assess the occurrence and intensity of mystical-type experiences occasioned by psilocybin (9,10). Psilocybin occasioned mystical experiences are defined by acute feelings of unity, sacredness, a noetic quality, positive mood, transcendence of space/time, and ineffability (6), and have previously shown a significant association with successful psilocybin-facilitated smoking cessation outcomes at 6-month follow-up (11). The MEQ30 was completed at the conclusion of each psilocybin session approximately 7 hours after drug administration. Participants responded based on their experience during each particular session day.

Data Analysis

Participants were judged abstinent if breath CO value was ≤6ppm (12), urinary cotinine was <200 ng/mL (13), and if no smoking was reported on the TLFB for the previous 7 days. Urine samples testing negative for recent smoking were scored as 0 ng/mL for all analyses, as laboratory results did not provide specific values for negative (<200 ng/mL) samples. Participants who did not report to a follow-up visit were considered to have smoked. The three participants who did not complete a long-term follow-up (which occurred at a mean of 30 months post-TQD for those who completed) had been confirmed as daily smokers at the 12-month follow-up. Thus, for these three individuals, carbon monoxide, urine cotinine, and TLFB self-reported daily smoking data for the long-term follow-up were imputed using their individual 12-month follow-up values.

Repeated measures ANOVA tested for changes in TLFB self-reported smoking from study intake to long-term follow-up. Planned comparison two-tailed paired t-tests were used to compare TLFB data between study intake and each of the following time points: end of treatment (10 weeks post-TQD), and 6-month, 12-month, and long-term follow-ups.

Descriptive statistics were calculated using Persisting Effects Questionnaire data to assess long-term positive and negative changes, personal meaning, and spiritual significance attributed to psilocybin session experiences one week after each session, and at 12-months post-TQD.

To examine the hypothesis that greater mystical-type effects and more positive attributions regarding psilocybin sessions would be associated with greater smoking cessation success, Pearson’s correlations were calculated between psilocybin session ratings (i.e., individuals’ mean MEQ30 score across psilocybin sessions from the end of each session day, and individuals’ mean ratings of personal meaning and spiritual significance across psilocybin sessions from one week after each session) and long-term change scores on each smoking-related measure (i.e., breath CO, cotinine, TLFB). Change scores were calculated as each participant’s score at study intake subtracted from that participant’s score at long-term follow-up. For the TLFB this was calculated as mean cigarettes per day (CPD) in the 30 days preceding study intake, subtracted from mean CPD from TQD to long-term follow-up. All datasets examined via correlational analyses were normally distributed as determined by Dallal-Wilkinson-Lilliefor corrected Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests at an alpha level of 0.05 (14).

Results

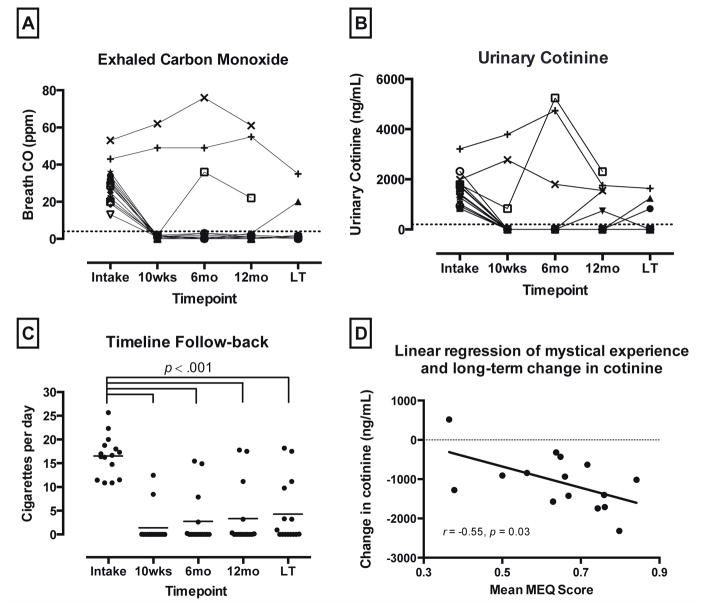

All 15 participants completed a 12-month follow-up. Twelve (80%) returned for a long-term follow-up (mean 30 months post-TQD; range = 16–57 months) and provided data regarding current smoking and past treatment experience. At 12-month follow-up, 10 participants (67%) were biologically confirmed as smoking abstinent, with 8 of these participants reporting continuous abstinence since their TQD. At long-term follow-up, nine participants (60%) were biologically confirmed as smoking abstinent, with 7 of these participants reporting continuous abstinence since their TQD (Figure 1A–C).

Figure 1.

(A) Exhaled carbon monoxide (CO) shown for each participant from baseline through long-term follow-up (LT). (B) Urine cotinine levels shown for each participant from baseline through long-term follow-up. (C) Timeline Follow-back (TLFB) data of self-reported daily smoking; individual data points show individual participant data, with the group mean indicated by horizontal line; horizontal brackets indicate significant reductions between intake and each of 4 follow-up assessments (2-tailed paired t-tests, p < 0.001). (D) Relationship between average scores on the Mystical Experience Questionnaire (MEQ30) at the conclusion of each psilocybin session, and change in urinary cotinine levels from study intake to long-term follow-up. Data points show data from each of the 15 individual participants with best-fit linear regression.

Repeated measures ANOVA found significant change in self-reported smoking on the TLFB from study intake through the four follow-up time points at 10 weeks, 6 months, 12 months, and a mean of 30 months post-TQD (F 2,23 = 81.4; p < 0.001). Planned comparison two-tailed paired t-tests showed a significant decrease in self-reported daily smoking between study intake and the four follow-up time points, from a mean (SD) of 16.5 (4.3) CPD at study intake, to 1.4 (3.8) CPD at 10 weeks (t14 = 19.4, p < 0.001); 2.7 (5.5) CPD at 6-months (t14 = 11.6, p < 0.001); 3.3 (6.5) CPD at 12-months (t14 = 9.2, p < 0.001); and 4.3 (6.6) CPD at long-term follow-up (t14 = 9.1, p < 0.001).

Positive persisting effects were rated higher than negative persisting effects across all six domains of the Persisting Effects Questionnaire, with average negative effects scores ranging from 3.2 to 8.1% of maximum possible score, and average positive effects scores ranging from 53 to 64% of maximum possible score (Table 1). For the final question regarding effects on well-being or life satisfaction attributed to psilocybin experiences or contemplation of those experiences, one participant deviated from instrument instructions by endorsing both −3 (decreased very much) and +3 (increased very much) at the 12-month follow-up. We therefore excluded this person’s data on this single item from the results reported in Table 1. No other participants endorsed any level of decrease in well-being or life satisfaction related to psilocybin session experiences at the 12-month follow-up.

Table 1.

Persisting Effects Questionnaire Ratings at one week after each psilocybin session, and 12 months after Psilocybin Session 1*

| Subscale/Item | Mean (SEM) Session 1 |

Mean (SEM) Session 2 |

Mean (SEM) Session 3 a |

Mean (SEM) 12 months |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive attitudes about life | 49.3 (6.5) | 63.2 (4.2) | 69.7 (6.0) | 63.5 (5.9) |

| Negative attitudes about life | 10.4 (3.2) | 6.3 (1.4) | 5.5 (1.4) | 7.0 (2.8) |

| Positive attitudes about self | 42.2 (6.6) | 57.7 (5.2) | 65.3 (5.8) | 60.5 (5.8) |

| Negative attitudes about self | 10.4 (2.4) | 6.1 (1.3) | 6.1 (1.3) | 8.1 (3.1) |

| Positive mood changes | 34.6 (6.0) | 53.5 (5.8) | 62.0 (8.4) | 53.0 (6.4) |

| Negative mood changes | 14.1 (5.4) | 4.4 (1.9) | 5.4 (4.5) | 7.0 (3.6) |

| Altruistic/positive social effects | 34.9 (7.8) | 56.3 (6.0) | 62.2 (7.1) | 57.6 (6.2) |

| Antisocial/negative social effects | 3.5 (1.7) | 2.8 (1.7) | 3.7 (2.2) | 6.5 (2.6) |

| Positive behavior changes | 52.9 (9.3) | 65.3 (7.9) | 80.0 (4.9) | 64.0 (6.8) |

| Negative behavior changes | 7.1 (5.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 3.3 (2.3) | 4.0 (4.0) |

| Increased spirituality | 40.0 (7.4) | 55.1 (6.0) | 60.5 (7.1) | 55.2 (6.6) |

| Decreased spirituality | 3.4 (1.3) | 1.2 (0.6) | 1.0 (0.5) | 3.2 (1.6) |

| How personally meaningful was the experience? (score range: 1–8) b | 5.4 (0.5) | 6.3 (0.2) | 6.3 (0.3) | 7.0 (0.2) |

| How spiritually significant was the experience? (score range: 1–6) c | 3.4 (0.4) | 4.2 (0.2) | 4.4 (0.4) | 5.1 (0.3) |

| Did the experience change your sense of well-being or life satisfaction? (score range: −3 to +3) d | 1.4 (0.5) | 2.5 (0.2) | 2.7 (0.3) | 2.1 (0.3) |

Data are mean scores with 1 SEM shown in parentheses (N=15); data on attitudes, mood, altruistic/social effects, and behavior changes are expressed as percentage of maximum possible score; data for the final three questions are raw scores.

For Session 3 scores N=12, as 3 participants declined an optional third psilocybin session.

Rating scale: 1=no more than routine, everyday experiences. 2=similar to meaningful experiences that occur on average once or more a week. 3=similar to meaningful experiences that occur on average once a month. 4=similar to meaningful experiences that occur on average once a year. 5=similar to meaningful experiences that occur on average once every 5 years. 6=among the 10 most meaningful experiences of my life. 7=among the 5 most meaningful experiences of my life. 8=the single most meaningful experience of my life.

Rating scale: 1=not at all. 2=slightly. 3=moderately. 4=very much. 5=among the 5 most spiritually significant experiences of my life. 6=the single most spiritually significant experience of my life.

Rating scale: −3=decreased very much. −2=decreased moderately. −1=decreased slightly. 0=no change. 1=increased slightly. 2=increased moderately. 3=increased very much.

The participant endorsing mixed results for well-being or life-satisfaction at the 12-month follow-up attributed the decrease in well-being or life-satisfaction to psilocybin session content in which she reported re-experiencing traumatic childhood memories. This individual was referred to additional counseling, which she reported to be helpful in integrating these experiences and resolving associated difficulty. One other participant sought outside counseling after their psilocybin session experiences, although this was reportedly undertaken with the intention of personal growth and self-improvement. Consistent with previously published data (4), no participants reported an increase in bothersome visual disturbances at the 12-month follow-up relative to baseline, and no clinically significant psychological sequelae were spontaneously reported at the long-term follow-up.

Participants attributed great personal meaning and spiritual significance to their psilocybin experiences at 12-months post-TQD, with 13 (86.7%) rating these experiences among the five most personally meaningful of their lives, and 13 (86.7%) rating them among the five most spiritually significant experiences of their lives.

Change in urine cotinine levels from study intake to long-term follow-up were significantly correlated with mean ratings of personal meaning of psilocybin session from one week after each session (r = −0.55, p = 0.04), and mean MEQ30 scores from the end of each session day (r = −0.55, p = 0.03; Figure 1D). The 7 other correlations between psilocybin session attributes and smoking cessation success did not reach significance (p range: .10 to .36) but were consistently in the predicted direction with moderate effect sizes (r range: −.25 to −.44).

Discussion

These results, together with previously reported findings indicate that psilocybin may be a feasible adjunct to smoking cessation treatment. In controlled studies, the most effective smoking cessation medications typically demonstrate less than 31% abstinence at 12 months post-treatment (15,16), whereas the present study found 60% abstinence more than a year after psilocybin administration. However, the current findings are limited by the small sample, open-label design, and lack of control condition, which preclude making definitive conclusions about efficacy. Furthermore, participant self-selection bias may have played a role in observed success rates, as the study enrolled only individuals motivated to quit and willing to undergo a time-intensive experimental treatment for no monetary compensation.

Additional, carefully controlled research in larger, more diverse samples is necessary to determine efficacy. Toward this end, the authors are currently conducting a randomized comparative efficacy trial in a larger study sample (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT01943994). This study is evaluating smoking cessation outcomes between individuals receiving a single high dose (30 mg/70kg) of psilocybin vs. a standard 8 to 10 week course of nicotine replacement therapy (i.e., patch), with both groups receiving the same cognitive behavioral smoking cessation intervention.

Nevertheless, the present results suggest persisting effects of psilocybin-facilitated treatment well beyond the time course of acute drug action. Consistent with previous findings, results indicated greater mystical-type effects and more positive attributions regarding psilocybin sessions were associated with greater smoking cessation success. The only significant correlations were between cotinine reductions and mystical-type psilocybin effects, and between cotinine reductions and ratings of session personal meaning. However, all other correlations between subjective effects of psilocybin and change in smoking-related measures were in the predicted direction with a moderate effect size. Therefore, the failure of these other correlations to reach significance might constitute a type II error related to small sample size.

While the intervention used in this study was not explicitly “spiritual” in nature, participants consistently attributed a high degree of spiritual significance to their psilocybin session experiences, raising questions about the role of spirituality in smoking cessation. Several studies suggest that increased levels of spirituality are associated with improved treatment outcomes in substance dependence recovery (17–20), and pilot survey data indicate that 78% of smokers reported that spiritual resources would be helpful in quitting smoking (21). The lasting psychological and behavioral shifts observed following psychedelic administration may be mediated in part by the salient, often subjectively positive acute effects of 5-HT2AR agonists, which have sometimes been characterized as mystical or transcendent (7,11,22).

Combined with historical data suggesting high success rates of psychedelic-facilitated treatment of alcoholism approximately doubling the odds of success at initial follow-up (23), and promising recent pilot data on psilocybin-facilitated treatment of alcohol dependence (24), the present findings indicate that 5-HT2AR agonists may hold therapeutic potential in treating a variety of substance use disorders in the context of a structured treatment program. Considering the often chronic and intractable nature of addictive disorders, further investigation of psychedelic-facilitated treatment of addiction and underlying neurobiological mechanisms represent important future directions for research.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: The Beckley Foundation provided initial funding for this research, with continued funding provided by Heffter Research Institute. Support for Dr. Garcia-Romeu was provided by National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant T32DA07209. Support for Dr. Griffiths was provided in part by NIDA Grant R01DA003889.

Amanda Feilding of the Beckley Foundation provided initial funding and encouragement for this research, with continued funding provided by Heffter Research Institute. Mary Cosimano, MSW, Tehseen Noorani, PhD, Margaret Klinedinst, BS, Patrick Johnson, PhD, Matthew Bradstreet, PhD, Rosemary Scavullo-Flickinger, BA, Fred Reinholdt, MA, Samantha Gebhart, BS, Grant Glatfelter, BS, Toni White, BA, and Jefferson Mattingly assisted in data collection. Annie Umbricht, MD, and Leticia Nanda, CRNP provided medical screening and coverage. William A. Richards, STM, PhD provided valuable clinical consultation.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: Dr. Griffiths is on the board of directors of the Heffter Research Institute.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2011: warning about the dangers of tobacco. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cahill K, Stevens S, Lancaster T. Pharmacological treatments for smoking cessation. JAMA. 2014;311(2):193–194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.283787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mottillo S, Filion KB, Bélisle P, Joseph L, Gervais A, O’Loughlin J, Paradis G, Pihl R, Pilote L, Rinfret S, Tremblay M. Behavioural interventions for smoking cessation: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur Heart J. 2009 Mar 1;30(6):718–30. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson MW, Garcia-Romeu A, Cosimano MP, Griffiths RR. Pilot study of the 5-HT2AR agonist psilocybin in the treatment of tobacco addiction. J Psychopharmacol. 2014;28(11):983–992. doi: 10.1177/0269881114548296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten R, Allen J, editors. Measuring Alcohol Consumption. Rockville, MD: Humana Press; 1992. pp. 207–224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Griffiths R, Richards W, McCann U, Jesse R. Psilocybin can occasion mystical-type experiences having substantial and sustained personal meaning and spiritual significance. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;187(3):268–283. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0457-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Griffiths RR, Richards WA, Johnson MW, et al. Mystical-type experiences occasioned by psilocybin mediate the attribution of personal meaning and spiritual significance 14 months later. J Psychopharmacol. 2008;22(6):621–632. doi: 10.1177/0269881108094300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Griffiths RR, Johnson MW, Richards WA, et al. Psilocybin occasioned mystical-type experiences: immediate and persisting dose-related effects. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;218(4):649–665. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2358-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacLean KA, Leoutsakos JMS, Johnson MW, Griffiths RR. Factor analysis of the mystical experience questionnaire: A study of experiences occasioned by the hallucinogen psilocybin. J Sci Study Relig. 2012;51(4):721–737. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5906.2012.01685.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barrett FS, Johnson MW, Griffiths RR. Validation of the revised Mystical Experience Questionnaire in experimental sessions with psilocybin. J Psychopharmacol. 2015;29(11):1182–1190. doi: 10.1177/0269881115609019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garcia-Romeu A, Griffiths R, Johnson M. Psilocybin-occasioned mystical experiences in the treatment of tobacco addiction. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2014;7(3):157–164. doi: 10.2174/1874473708666150107121331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Javors MA, Hatch JP, Lamb RJ. Cut-off levels for breath carbon monoxide as a marker for cigarette smoking. Addiction. 2005;100(2):159–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bramer S, Kallungal B. Clinical considerations in study designs that use cotinine as a biomarker. Biomarkers. 2003;8(3–4):187–203. doi: 10.1080/13547500310012545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dallal GE, Wilkinson L. An analytic approximation to the distribution of Lilliefors’s test statistic for normality. The American Statistician. 1986 Nov 1;40(4):294–6. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hays JT, Ebbert JO, Sood A. Efficacy and safety of varenicline for smoking cessation. Am J Med. 2008;121(4):S32–S42. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tonnesen P, Tonstad S, Hjalmarson A, et al. A multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 1-year study of bupropion SR for smoking cessation. J Intern Med. 2003;254(2):184–192. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2003.01185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coyle C, Crum RM, Ford DE. Associations between spirituality and substance abuse symptoms in the Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area follow-up, 1993–1996. J Addict Dis. 2006;25(4):125–132. doi: 10.1300/J069v25n04_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piderman KM, Schneekloth TD, Pankratz VS, et al. Spirituality in alcoholics during treatment. Am J Addict. 2007;16(3):232–237. doi: 10.1080/10550490701375616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piedmont RL. Spiritual transcendence as a predictor of psychosocial outcome from an outpatient substance abuse program. Psychol Addict Behav. 2004;18(3):213–222. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.18.3.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zemore SE. A role for spiritual change in the benefits of 12-step involvement. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(s3):76s–79s. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gonzales D, Redtomahawk D, Pizacani B, et al. Support for spirituality in smoking cessation: results of pilot survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9(2):299–303. doi: 10.1080/14622200601078582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacLean KA, Johnson MW, Griffiths RR. Mystical experiences occasioned by the hallucinogen psilocybin lead to increases in the personality domain of openness. J Psychopharmacol. 2011;25(11):1453–1461. doi: 10.1177/0269881111420188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krebs TS, Johansen PØ. Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) for alcoholism: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Psychopharmacol. 2012;26(7):994–1002. doi: 10.1177/0269881112439253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bogenschutz MP, Forcehimes AA, Pommy JA, Wilcox CE, Barbosa PCR, Strassman RJ. Psilocybin-assisted treatment for alcohol dependence: A proof-of-concept study. J Psychopharmacol. 2015;29(3):289–299. doi: 10.1177/0269881114565144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]