Abstract

We report a case of a 45-year-old man with a complaint of both leg weakness and hypoesthesia. Radiological evaluation revealed an osteolytic lesion of the ninth thoracic vertebra. The patient underwent posterior corpectomy with total excision of the tumor, mesh cage insertion with posterior screw fixation and subsequent radiotherapy. Histology confirmed the diagnosis of Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH). This case report presents the diagnostic work-up, histopathological evaluation, and the treatment procedures of rare LCH in the thoracic spine.

Keywords: Langerhans cell histiocytosis, Thoracic spine, Adults

INTRODUCTION

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a clonal proliferation of Langerhans cells occurring as an isolated lesion or as part of a systemic (multifocal) proliferation10). LCH is a rare disorder characterized by an excessive proliferation of pathologic Langerhans cells. The disease varies widely in clinical presentation from localized involvement of a single bone to a widely disseminated life-threatening disease7). Since the cell of origin in this disease is now clearly defined, the term LCH should substitute all the previously used terms, such as histiocytosis X, eosinophilic granuloma, Hand-Schuller-Christian disease and Letterer-Siwe disease1). We report a case of 45-year-old man diagnosed as LCH of the thoracic spine with the diagnostic workup, histopathological evaluation and treatment procedures.

CASE REPORT

A 45-year-old man presented with 1 month of left flank pain, 10 days of hypoesthesia and weakness at both lower extremity. He also complained that he had difficulty going up the stairs and keeping his balance. There was no history of systemic illness and family history. On examination, he had elevated deep tendon reflex of right knee, motor weakness of both lower extremity (grade 4) and hypoesthesia below T10 dermatome. His body temperature was normal and result of blood tests, such as white blood cell (WBC), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP), were all slightly increased (WBC, 11.9 K/μL [4 K/μL–10 K/μL]; ESR, 10 mm/hr [0–28 mm/hr]; CRP, 1.18 mg/dL [0–0.3 mg/dL]).

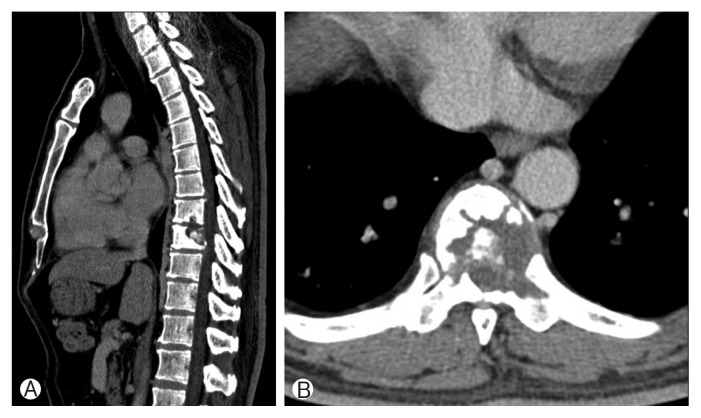

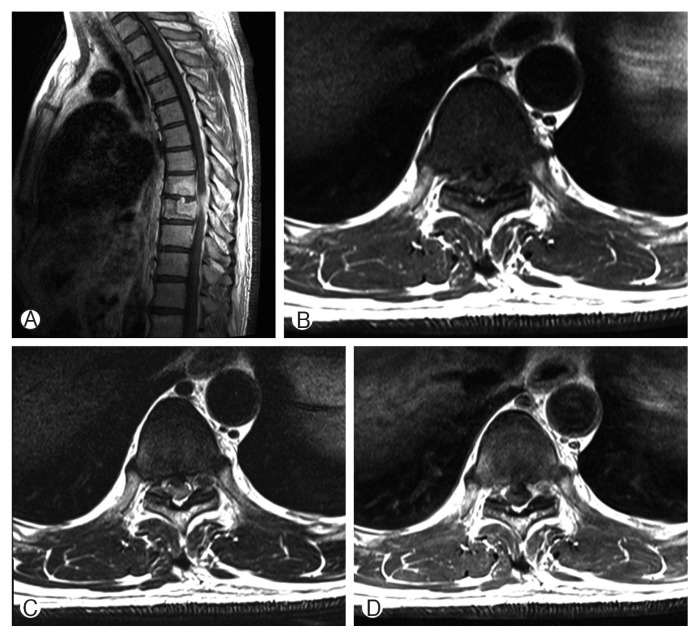

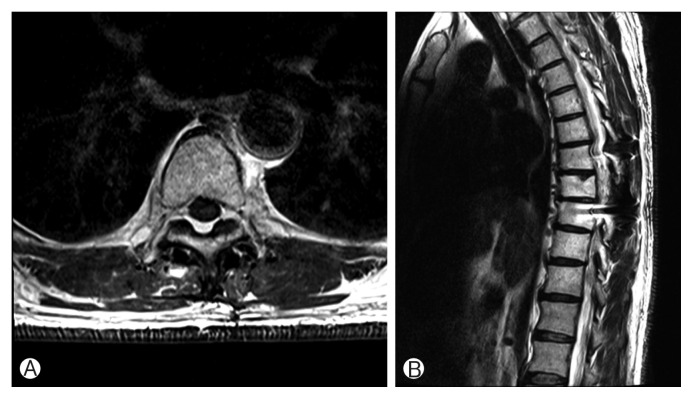

Computed tomography (CT) scans revealed fracture of T8, T9 vertebral body by bone tumor (Fig. 1). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed pathologic fracture of T9 vertebral body by bone tumor, T8–10 myelopathy and cord compression (Fig. 2). Whole body PET showed focal hypermetabolic lesion around the T9 spine area. There was no other abnormal finding. So we assumed that the lesion is a primary bone tumor.

Fig. 1.

(A, B) Computed tomography scans revealed pathologic fracture of T8, T9 vertebral body by bone tumor.

Fig. 2.

Magnetic resonance imaging showed pathologic fracture of T9 vertebral body by bone tumor, T8–10 myelopathy and cord compression. Gadolinium enhanced sagittal image (A), T1-weighted (B), T2-weighted (C), and Gadolinium enhanced axial image (D).

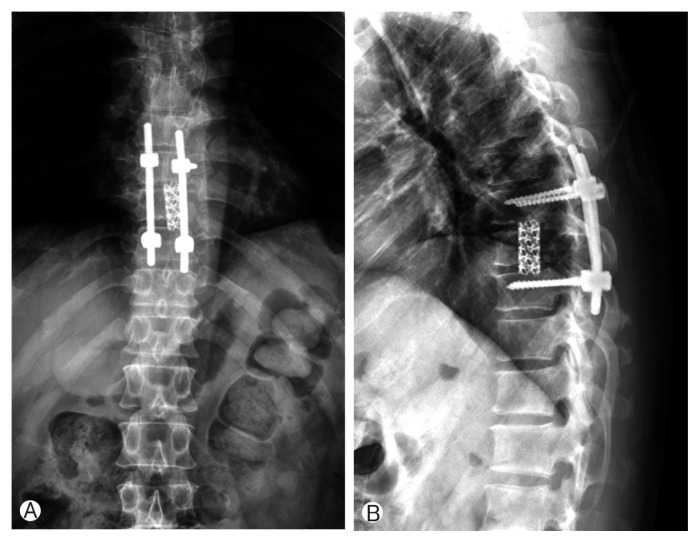

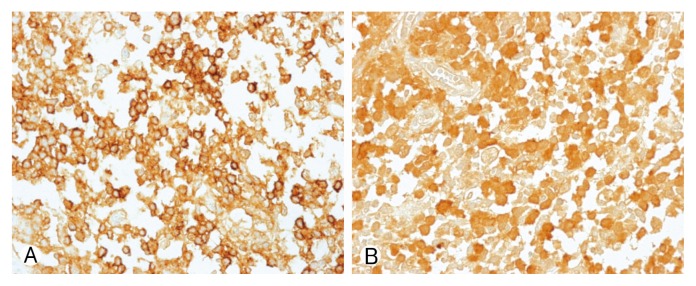

Due to motor weakness and radiologic finding, the patient underwent T9 corpectomy and mesh cage insertion with T8–10 posterior screw fixation(Figs. 3, 4). Pathological examination confirmed a diagnosis of LCH. There was a positive immunohistochemical reaction of CD1a and S-100 protein (Fig. 5). Then he underwent radiotherapy at T8–10 spine (200 cGy, 10 times). After the operation, the patient recovered both leg weakness and hypoesthesia. The patient gave a written informed consent and was enrolled in the study. Now he has been followed for almost 6 years without any recurrence.

Fig. 3.

(A, B) Immediate postoperative X-ray showed T9 corpectomy and mesh cage insertion with T8–10 posterior screw fixation.

Fig. 4.

(A, B) After 3 years of follow-up, magnetic resonance imaging showed completely disappeared Langerhans cell histiocytosis.

Fig. 5.

Pathological examination confirmed a diagnosis of Langerhans cell histiocytosis. There was a positive immunohistochemical reaction of CD1a (×400) (A) and S-100 protein (×400) (B).

DISCUSSION

LCH is a rare disease with a rather unpredictable course since it can spontaneously resolve or progress to a disseminated form, compromising vital functions with occasionally fatal consequences. The etiology of LCH remains unknown, and inconsistencies in the published literature also reflect a lack of understanding about the cause of the disease. LCH is mostly seen in children and adolescents. The peak incidence is between ages 5 and 10 years in about 80% of the cases3,6). The most frequently reported anatomic sites are those in the skull (26%), vertebra (7%), ribs (12%), upper and lower jaw(9%), and bones of extremities (11%)2,8). In the spine, LCH mainly involves the vertebral bodies, with a predilection for the thoracic spine (54%) followed by the lumbar (35%) and cervical spine (11%)5,6). The present case was a solitary osseous lesion with no evidence of systemic symptoms and within T9 body.

Single or multiple sharply-circumscribed osteolytic lesions can be seen by the radiological studies. The most common radiographic features in spinal LCH in both groups were lytic lesions of the vertebra, which usually led to vertebral collapse. The typical sign of vertebral collapse was a flattening of the vertebral body (vertebra plana)3). In our case, conventional X-ray, CT and MRI scans were performed and an osteolytic destruction of the T9 vertebra was detected during the work-up.

There is a variety of treatment strategies mentioned in the literature. Many studies have shown excellent healing and resolution of LCH using a variety of treatment including bracing, surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and even no therapy for its excellent prognosis4). Intralesional corticosteroid injection9) or operative treatment with curettage, lesionectomy, corpectomy have been described3,9). Postoperative chemotherapy or radiotherapy are also mentioned in the literature3,9). Spontaneous regression of the bone lesion after 6 months has also been reported1,8).

In case of solitary spinal lesion with neurological impairment, surgical treatment is recommended. But the role of postoperative radiotherapy is still controversial8). In our case, we performed corpectomy and mesh cage insertion with posterior fixation. Then the patient underwent radiotherapy. After 6-year follow-up, no evidence of recurrence or neurological deficits has been identified.

CONCLUSION

We report our experience with a very rare case of LCH of the thoracic spine in 45-year-old man. The patient had a solitary spinal lesion and underwent surgical treatment and radiotherapy successfully.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aricò M, Girschikofsky M, Généreau T, Klersy C, McClain K, Grois N, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in adults. Report from the International Registry of the Histiocyte Society. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:2341–2348. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(03)00672-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bertram C, Madert J, Eggers CL. Eosinophilic granuloma of the cervical spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002;27:1408–1413. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200207010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dickinson LD, Farhat SM. Eosinophilic granuloma of the cervical spine. A case report and review of the literature. Surg Neurol. 1991;35:57–63. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(91)90204-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howarth DM, Gilchrist GS, Mullan BP, Wiseman GA, Edmonson JH, Schomberg PJ. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: diagnosis, natural history, management, and outcome. Cancer. 1999;85:2278–2290. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990515)85:10<2278::aid-cncr25>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ippolito E, Farsetti P, Tudisco C. Vertebra plana. Long-term follow-up in five patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66:1364–1368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kilborn TN, Teh J, Goodman TR. Paediatric manifestations of Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a review of the clinical and radiological findings. Clin Radiol. 2003;58:269–278. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(02)00537-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ladisch S. Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Curr Opin Hematol. 1998;5:54–58. doi: 10.1097/00062752-199801000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scarpinati M, Artico M, Artizzu S. Spinal cord compression by eosinophilic granuloma of the cervical spine. Case report and review of the literature. Neurosurg Rev. 1995;18:209–212. doi: 10.1007/BF00383729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simanski C, Bouillon B, Brockmann M, Tiling T. The Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis (eosinophilic granuloma) of the cervical spine: a rare diagnosis of cervical pain. Magn Reson Imaging. 2004;22:589–594. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Willman CL, Busque L, Griffith BB, Favara BE, McClain KL, Duncan MH, et al. Langerhans’-cell histiocytosis (histiocytosis X)--a clonal proliferative disease. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:154–160. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199407213310303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]