Abstract

The neurogenic tumor of frequent occurrence in the presacral area is a schwannoma. Giant presacral schwannoma has a risk for anterior surgical approach because of its massive size and proximity to abundant vascularity of presacral region. We report a single stage posterior approach for total resection of a giant presacral schwannoma. A 40-year-old female patient experienced left buttock pain and tingling sensation at left S1 dermatome. Magnetic resonance imaging showed that the presacral huge mass at S1–3 level with osseous extension and structural remodeling in left sacral ala. The presacral mass was ranging in maximum diameter from 8.0 to 8.6 cm. S2 foramen laminectomy was performed to expose the mass. The tumor capsule and the root were carefully dissected away. The tumor was removed while preserving the capsule by dissecting the plane between the inner wall of the capsule and the tumor. The single stage posterior approach for presacral giant schwannoma is feasible, and it can be a good surgical alternative to prevent pelvic organ or vascular damage and anterior approach related dystocia and infertility.

Keywords: Presacral giant schwannoma, Excision, Neurogenic tumor, Posterior approach

INTRODUCTION

Tumors in the presacral space are uncommon. Presacral neurogenic tumors are even rarer with 10%–15% of the presacral region tumors15). The neurogenic tumor of frequent occurrence in the presacral area is the schwannoma13). It is often delayed diagnosis due to nonspecific clinical symptom or absence of clinical signs before occurring irritation of intrapelvic organs6,18). Schwannoma in the presacral regions grows slowly6). The tumor is placed deep in the pelvic cavity and mass that grows out where anterior to the sacrum2). Benign schwannoma does not invade the adjacent organs, and the tumor causes symptoms by taking over the place of the adjacent organs18). Therefore, it affects the nearby organs slowly in the large pelvic cavity. For that reason, presacral schwannoma can grow to an enormous size and frequently diagnosed at a progressed stage5,19). Not a few authors argued that the treatment of choice for tumors is complete surgical excision1,3,10,12,19). Nevertheless, giant presacral schwannoma has a risk for surgical approach because of its huge size and proximity to abundant vascularity of presacral region7,10). In literatures, the approach to the tumor was described in various directions3,16,17,19). We report a single stage posterior approach for total resection of a giant presacral schwannoma to prevent serious complications related to the anterior approach.

CASE REPORT

1. Case Presentation

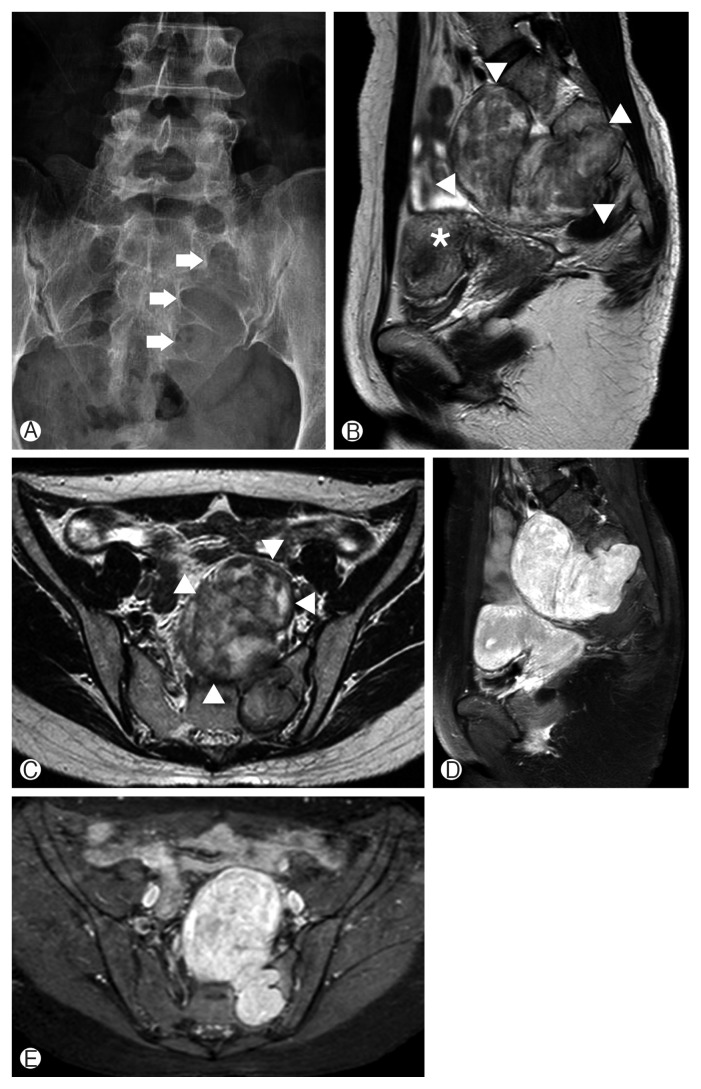

A 40-year-old female patient experienced pain on her left buttock and tingling sensation at left S1 dermatome for 10 months. A physical examination reported left leg paresthesia, but no motor weakness observed. The patient had prior surgery for ovarian cyst 5 years ago. The plain radiograph of the sacrum revealed osteolytic lesions at left S1–3 level. The details of bony involvement and remodeling in left sacral ala could confirm at computed tomography (CT) image. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis showed that the presacral huge mass has heterogeneous iso/high intensity on T2-weighted images and positive on T1 enhancement image (Fig. 1). The presacral mass was ranging in maximum diameter from 8.0 to 8.6 cm. The tumor is encapsulated and has clear margin. The mass origin was abutting to the left S2 nerve root. There was no invasion of adjacent organs, though it was an anterior migration of the pelvic organs such as uterus by the tumor. A single stage posterior approach was utilized for tumor resection. The tumor was removed totally by piecemeal fashion without sacrifice of the left S2 root. Postoperative MRI showed complete removal of the tumor. The patient had a recovery from the pain and no neurological deficit. The tumor did not demonstrate any recurrence on postoperative 2 years MRI (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Preoperative radiographic images of a mass lesion located in the presacral space. (A) Anterior posterior plain radiograph of the sacrum demonstrating the widened neural foramen at the left S1–3 level (arrows). (B, C) Sagittal and axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance (MR) images showing a heterogeneous iso/high intensity mass (arrowheads) at the presacral area displacing the uterus (asterisk). (D, E) Sagittal and axial T1-weighted postcontrast MR images showing a well-enhanced mass compressing the pelvic organs.

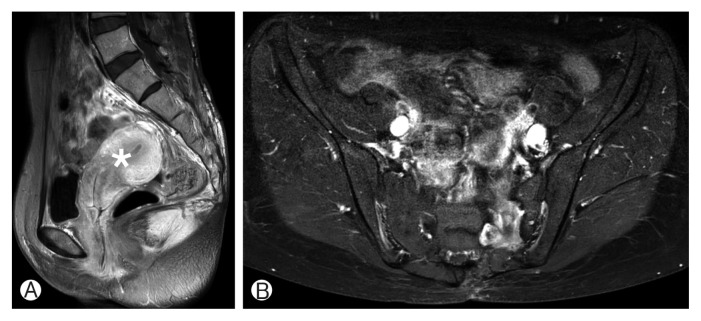

Fig. 2.

(A, B) Postoperative 2-year magnetic resonance imaging showing no evidence of a recurrence. The compressed pelvic organs including the uterus (asterisk) are relieved after surgery.

2. Surgical Technique

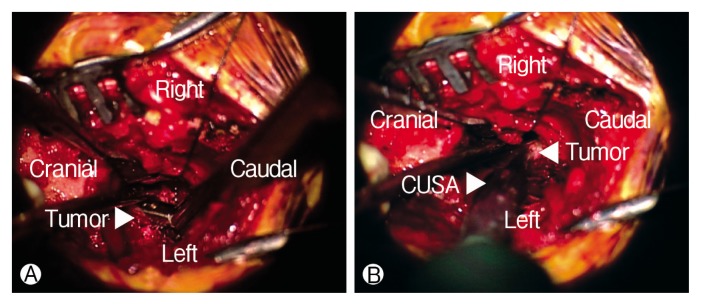

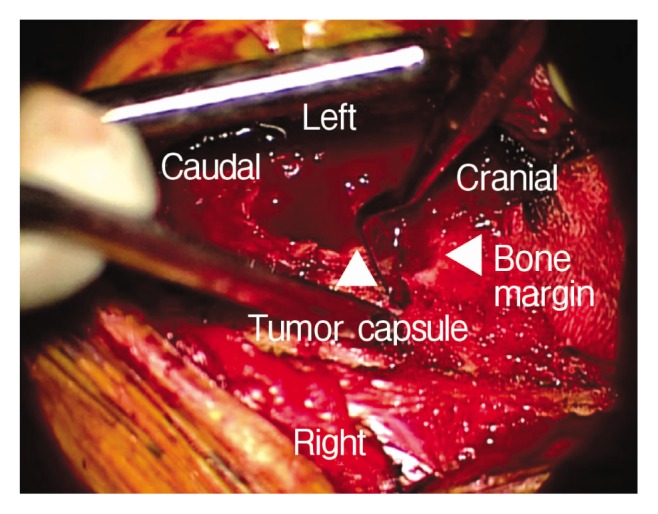

The patient was anesthetized and placed in the prone position. A lateral portable plain radiograph was taken to guide the location of the incision. The midline incision performed including the S1–3 levels. The subperiosteal dissection was done and left S2 foramen was exposed. The S2 foramen widened, and yellow-whitish rubbery mass observed. Laminectomy was performed at the S2 foramen for exposing the margin of mass. The tumor had the clear margin with capsule and was thought to originate from the S2 root. The tumor capsule and the root carefully dissected away. The intraoperative nerve monitoring used for avoiding unintended nerve injury, and there was no change during surgery. The capsules were identified by separating the outer boundary of the tumor from the bone (Fig. 3). The capsule was incised with No. 15 blade and piece of the tumor was obtained for frozen biopsy. The result of frozen biopsy was a schwannoma. After the capsule was tagged by a suture material on the both side, the tumor was removed by piecemeal fashion make space. The tumor was removed while preserving the capsule by dissecting the plane between the inner wall of the capsule and the tumor. The dissector was inserted into the border of a tumor and was peeled off from the inner wall of the capsule like a lever. The piecemeal excision did by tumor forceps and cavitron ultrasonic surgical aspirator at a peeled tumor (Fig. 4). This process was repeated to decrease the size of the tumor. Finally, the upper and lower pole of the reduced tumor was identified and removed totally. After grossly total resection of the tumor, the inside of the capsule was examined in each direction to confirm whether the remnant tumor remained. The blind points in the capsule were confirmed using a surgical mirror. After removing the huge tumor, pulsation of the peritoneal membrane was observed in the surgical field.

Fig. 3.

The outer border of the tumor was dissected from bone to confirm the capsule.

Fig. 4.

(A, B) The piecemeal excision by tumor forceps and cavitron ultrasonic surgical aspirator.

DISCUSSION

In general, although the giant schwannoma grows slowly, surgical treatment is recommended because of the mass effect of the tumor in the presacral region. The tendency of a tumor with noninvasive growth and thick capsule can make complete resection of presacral schwannomas possible6). Many authors have been described three approaches for presacral tumor resection: anterior (open or laparoscopic), posterior, or an anterior-posterior combination14,17,19). The different surgical approaches are dependent on the extent of tumor involvement11,17,19). The previous researcher determined the surgical approach based on the classification claimed by Klimo et al.9). Tumors classified into four groups according to their growth pattern (type I, intra sacral canal; type II, through the intervertebral foramen into the presacral space; type III, both anterior and posterior to the sacrum; type IV, presacral space). Types II and III, located at a higher level than S1, were operated by the anterior-posterior combination approach. The anterior approach had been used in most cases of type IV. The posterior approach was considered to the cases of types I–III which lower than S1 level19). Sun et al.17) reported that the approach selected by S1, 2, 3 level involvement and tumor horizontal distance from the anterior edge of the sacrum. The tumor with only presacral growth was resected via an anterior approach. The cases of an anterior mass with distance less than 5 cm or sacral canal and post sacrum were required posterior approach. A combination approach appropriated for the mass below S3 with the length greater than 5 cm, or the S1, S2 involvement. Another investigator suggested that laparoscopic approach is feasible for presacral schwannoma7).

In this study, the tumor has grown forward out of left S2 neural foramen with S1–3 osseous extension and had a distance of greater than 5 cm from the anterior edge of the sacrum. We performed a complete resection of the tumor using the only posterior approach. The posterior approach was selected to prevent various problems that may occur in the anterior approach. The anterior approach related complications include massive bleeding, ureter injury, internal organ damage, anorectal dysfunction, and nerve damage. In the anterior approach, massive bleeding may develop by injury of the internal iliac vein, its branch and venous plexus in the adnexa17,20). Bleeding control from the tumor removal site is quite difficult because of the lack of compression by presacral fascia in the anterior approach19). There is a risk of dystocia and infertility for women of childbearing age16). The index patient wanted to have a baby as a fertile female. Therefore, we chose the posterior approach and used the character of the schwannomas. The tumor has a nature of the well-circumscribed and -encapsulated, moreover, it does not invade the adjacent organs directly and has not adhered to blood vessels3,6,12). The method peeling off the inner wall of the capsule and debulking the tumor internally while preserving the outer capsule is the key point of this technique. Using the method, the tumor can be removed without damage to the tissue outside the capsule. It has been reported that intralesional resection has favorable outcomes4,8). Additionally, the posterior approach has several advantages such as evident and familiar operating field, reduced the possibility of nerve injury, and favoring postoperative recovery16,19).

However, there are limitations of in this method. This surgical strategy should be applied to benign tumors, not to malignant one. If the tumor is large enough to infiltrate the abdominal cavity, the only posterior approach is not feasible.

CONCLUSION

There are several approaches to removal of the presacral giant schwannoma. The single stage posterior approach for presacral giant schwannoma is feasible, and it can be a good surgical alternative to prevent pelvic organ or vascular damage and anterior approach related dystocia and infertility.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alderete J, Novais EN, Dozois EJ, Rose PS, Sim FF. Morbidity and functional status of patients with pelvic neurogenic tumors after wide excision. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:2948–2953. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1478-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dang L, Liu X, Dang G, Jiang L, Wei F, Yu M, et al. Primary tumors of the spine: a review of clinical features in 438 patients. J Neurooncol. 2015;121:513–520. doi: 10.1007/s11060-014-1650-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Emohare O, Stapleton M, Mendez A. A minimally invasive pericoccygeal approach to resection of a large presacral schwannoma: case report. J Neurosurg Spine. 2015;23:81–85. doi: 10.3171/2014.11.SPINE14396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ganju A, Roosen N, Kline DG, Tiel RL. Outcomes in a consecutive series of 111 surgically treated plexal tumors: a review of the experience at the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center. J Neurosurg. 2001;95:51–60. doi: 10.3171/jns.2001.95.1.0051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hébert-Blouin MN, Sullivan PS, Merchea A, Léonard D, Spinner RJ, Dozois EJ. Neurological outcome following resection of benign presacral neurogenic tumors using a nerve-sparing technique. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:1185–1193. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31829e4e4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hughes MJ, Thomas JM, Fisher C, Moskovic EC. Imaging features of retroperitoneal and pelvic schwannomas. Clin Radiol. 2005;60:886–893. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jatal S, Pai VD, Rakhi B, Saklani AP. Presacral schwannoma: laparoscopic resection, a viable option. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4:176. doi: 10.21037/atm.2016.04.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim DH, Ryu S, Tiel RL, Kline DG. Surgical management and results of 135 tibial nerve lesions at the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center. Neurosurgery. 2003;53:1114–1124. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000089059.01853.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klimo P, Jr, Rao G, Schmidt RH, Schmidt MH. Nerve sheath tumors involving the sacrum. Case report and classification scheme. Neurosurg Focus. 2003;15:E12. doi: 10.3171/foc.2003.15.2.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuriakose S, Vikram S, Salih S, Balasubramanian S, Mangalasseri Pareekutty N, Nayanar S. Unique surgical issues in the management of a giant retroperitoneal schwannoma and brief review of literature. Case Rep Med. 2014;2014:781347. doi: 10.1155/2014/781347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li D, Guo W, Tang X, Ji T, Zhang Y. Surgical classification of different types of en bloc resection for primary malignant sacral tumors. Eur Spine J. 2011;20:2275–2281. doi: 10.1007/s00586-011-1883-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li Q, Gao C, Juzi JT, Hao X. Analysis of 82 cases of retroperitoneal schwannoma. ANZ J Surg. 2007;77:237–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2007.04025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Makni A, Fetirich F, Mbarek M, Ben Safta Z. Presacral schwannoma. J Visc Surg. 2012;149:426–427. doi: 10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Samarakoon L, Weerasekera A, Sanjeewa R, Kollure S. Giant presacral schwannoma presenting with constipation: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2012;6:285. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-6-285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santiago C, Lucha PA. Atypical presentation of a retrorectal ancient schwannoma: a case report and review of the literature. Mil Med. 2008;173:814–816. doi: 10.7205/milmed.173.8.814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saxena D, Pandey A, Bugalia RP, Kumar M, Kadam R, Agarwal V, et al. Management of presacral tumors: our experience with posterior approach. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;12:37–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2015.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun W, Ma XJ, Zhang F, Miao WL, Wang CR, Cai ZD. Surgical treatment of sacral neurogenic tumor: a 10-year experience with 64 cases. Orthop Surg. 2016;8:162–170. doi: 10.1111/os.12245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Theodosopoulos T, Stafyla VK, Tsiantoula P, Yiallourou A, Marinis A, Kondi-Pafitis A, et al. Special problems encountering surgical management of large retroperitoneal schwannomas. World J Surg Oncol. 2008;6:107. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-6-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wei G, Xiaodong T, Yi Y, Ji T. Strategy of surgical treatment of sacral neurogenic tumors. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34:2587–2592. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181bd4a2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Won TY, Oh JY, Cho CB, Cho CK. Unexpected disseminated intra-vascular coagulation after venous injury during anterior lumbar interbody fusion: a case report. Korean J Spine. 2010;7:111–115. [Google Scholar]