Abstract

Obesity predisposes an individual to develop numerous co-morbidities including type 2 diabetes and represents a major healthcare issue in many countries worldwide. Bariatric surgery can be an effective treatment option resulting in profound weight loss and improvements in metabolic health. However, not all patients achieve similar weight loss or metabolic improvements. Exercise is an excellent way to improve health, with well-characterized physiological and psychological benefits. This article reviews the evidence to determine whether there may be a role for exercise as a complementary adjunct therapy to bariatric surgery. Objectively measured physical activity data indicate that most bariatric surgery patients do not exercise enough to reap the health benefits of exercise. While there is a dearth of data on the effects of exercise on weight loss and weight loss maintenance following surgery, evidence from studies of caloric restriction and exercise suggest that similar adjunctive benefits may be extended to patients who perform exercise post bariatric surgery. Recent evidence from exercise interventions following bariatric surgery suggests that exercise may provide further improvements in metabolic health, compared to surgery induced weight loss alone. Additional randomized controlled exercise trials are now needed as the next step to more clearly define the potential for exercise to provide additional health benefits following bariatric surgery. This valuable evidence will inform clinical practice regarding much-needed guidelines for exercise following bariatric surgery.

Keywords: gastric bypass surgery, exercise, physical activity

The Problem: Obesity is a Disease with Few Effective Treatment Options

The incidence of obesity, defined as a body mass index (BMI) of >30 kg/m2, has reached epidemic levels in the US and other developed nations. In the U.S. between 2009 and 2010, the age-adjusted prevalence of obesity in adult men was 35.5% and 35.8% among in women1. Although there does appear to be a plateau with general obesity prevalence between 2011–2012 being similar to 2009–20102, projections indicate that by 2030, 86.3% of U.S. adults will be overweight or obese and 51% obese3. Moreover, the prevalence of severe obesity continues to rise4.

There are considerable negative health consequences associated with excess weight, to the extent that obesity has recently been classified as a disease by the American Medical Association5. Both overweight and obesity puts individuals at risk for adverse health outcomes including type 2 diabetes, cancer, hypertension and cardiovascular diseases6,7 as well as depression and other psychological disorders8 and is associated with significantly higher all-cause mortality9. Thus, it is critical to consider the most effective intervention strategies to lower the health risk and economic costs associated with obesity. Bariatric surgery is an effective treatment option with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) being the most commonly performed bariatric surgery procedure in the US. RYGB surgery results in dramatic weight loss and diabetes remission in a large percentage of patients15–17. In non-surgery patients, routine exercise is considered to be an important, if not necessary part of any long-term weight loss program, although performing exercise alone does not result in substantial body weight reduction in non-surgery patients18. Very little is known, however, about whether engaging in exercise post-surgery can provide additional improvement in health outcomes. This article will review the current evidence to determine whether there may be a role for exercise as a therapeutic option for the bariatric surgery patient with a focus on weight loss, maintenance of weight loss, and beneficial physiological/metabolic adaptations. While there are relatively few studies of exercise/physical activity in bariatric surgery patients to date, we will also consider evidence for the benefits of exercise from the context of non-surgery patients and diet induced calorie restriction. We will also identify future research directions and highlight important unanswered questions in this new and emerging field.

Exercise As An Adjunct Therapy For Further Weight Loss And Improved Body Composition Following Bariatric Surgery

Bariatric surgery produces significant weight loss and drastic improvements in metabolic health. It is not an infallible treatment option, however, and long-term effectiveness has not been clearly defined. One problem is the lack of studies reporting long term (>1 year) follow-up in cohorts with adequate retention rates14. A number of reports suggest that 10–30% of bariatric surgery patients experience suboptimal weight loss20,23,24. However, this number may be significantly higher when patients who drop out of the study are accounted for25. While further studies are needed to understand the physiological and behavioral origins of inter-patient variation in surgery induced weight loss, current evidence indicate that greater BMI, age, diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, cognitive function, personality, and mental health are strong predictors of suboptimal weight loss26–28. For bariatric surgery patients who experience suboptimal weight loss, exercise may prove to be an important adjunct therapy. Indeed, exercise administered alone is not generally viewed to cause substantial body weight reduction18. The consensus on the ability of exercise to induce weight loss is described in the Physical Activity Guidelines Committee Report, which states that exercise alone typically results in weight loss of <3% of initial body weight29. However, exercise in combination with diet induced caloric restriction does produce an additive reduction in body weight18, even in individuals with severe obesity30. However, there is scant equivalent evidence in the context of bariatric surgery. A recent study, which examined the efficacy of a 6-month exercise intervention (120 min/wk. of mostly treadmill walking) on severely obese participants, did not observe any additional impact on RYGB surgery-induced weight loss or fat mass31. These findings are similar to those of Shah et al. who showed that a high volume exercise prescription following bariatric surgery had no impact on body weight and waist circumference when compared to a control group32. One report indicated that excess weight loss was improved at 12-, but not 36-months postoperatively by attending semi-structured exercise education classes33. The lack of an exercise effect on weight in these intervention studies is likely due to the strong influence of surgery. These data do not, however, rule out the possibility that a higher dose/intensity of exercise may elicit additional weight loss, or alter body composition or regional adiposity in a favorable way, following surgery. For example, in non-surgery patients, aerobic exercise is particularly effective at reducing visceral adipose tissue (VAT)34, a fat depot that is strongly linked to hepatic insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes35.

A systematic review by Chaston et al. suggests that loss of fat free mass (skeletal muscle, bone and organs) accounted for 31.3% of weight loss with RYGB surgery39. The clinical significance of FFM loss has not been fully investigated, but may be undesirable if excessive40. FFM accounts for a significant portion of resting energy expenditure (REE)41 and regulation of core body temperature, and it has been hypothesized that FFM loss may predispose weight regain in the long term42. For the older bariatric surgery patient, the loss of skeletal muscle and bone density may have a negative impact on physical function, progression of sarcopenia and quality of life43. Exercise, particularly resistance exercise, is an excellent way to maintain muscle mass in older adults44 and may also be effective for the older bariatric surgery patient. In the context of diet induced calorie restriction, a number of randomized studies have shown that during 16 weeks of weight loss on a low calorie diet, supervised exercise alleviated the loss of FFM45–47. A report by Metcalf et al., indicates that duodenal switch patients who self report as exercisers (30 min of exercise per session, >3 sessions a week) have 28% higher loss of fat mass and 8% higher gain in lean mass when compared to a non-exercise group48. To date, the published data support a potential role for exercise to elicit positive changes in body composition following bariatric surgery. Large randomized controlled exercise trials with comprehensive phenotyping (metabolic and body composition) of participants are needed to provide the next level of evidence to investigate the possibility of exercise as a feasible adjunct therapy to bariatric surgery.

Exercise For Weight Loss Maintenance Following Bariatric Surgery?

A proportion of bariatric surgery patients also experience significant weight regain and attenuation in the recovery from comorbidities49–51. In the context of diet induced calorie restriction, maintaining weight loss is a well-recognized problem, with one report suggesting that 12–18 months following weight loss, 33–50% of initial weight loss is regained52. However, exercise has been shown to be beneficial for long term weight loss maintenance following calorie restriction53. Data from the National Weight Control Registry (NWCR)54 and from other investigations55,56 suggest that moderate intensity exercise is critical for maintaining weight loss. For example, an exercise intervention study by Jakicic et al., indicates that the addition of 275 min/wk. of physical activity in combination with a reduction in energy intake is necessary for maintenance of a 10% weight loss in overweight women53. The importance of higher doses of exercise to maintain weight loss has also been reported18. However, similar evidence has not been generated in the context of bariatric surgery, and it is not yet clear whether exercise may assist weight loss maintenance following surgery. Further exercise intervention trials are now needed to determine whether this is the case.

Can Exercise Provide Additional Metabolic Improvement Following Bariatric Surgery?

In addition to weight loss, bariatric surgery also rapidly improves glycemic control and insulin sensitivity, effects that occur over discrete time periods following surgery and are mediated by a number of mechanisms. Within weeks of surgery, caloric restriction improves hepatic insulin sensitivity as evidenced by decreased in HOMA-IR, a surrogate index of hepatic insulin sensitivity57,58. Hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp with stable isotopic tracer methodology confirms that endogenous glucose production, an indicator of hepatic insulin sensitivity, improves soon after RYGB surgery59. Studies utilizing the glucose clamp method also reveal that the immediate metabolic benefits of bariatric surgery do not extend to improvements in peripheral tissue insulin sensitivity59,62. Indeed, a report showed that 1-month following RYGB surgery and substantial weight loss (~11%), peripheral insulin sensitivity did not improve59. This is significant, however, as skeletal muscle is the primary peripheral tissue responsible for disposal of ~80% of glucose following a meal. The long term improvements in peripheral tissue insulin sensitivity following bariatric surgery occur in proportion to weight loss54,55 which typically consist of a ~50% reduced whole body fat mass and a ~60% decrease in visceral adipose tissue after one year73,74. However, even with significant weight loss one year following RYBG surgery, peripheral insulin sensitivity remains low compared to lean metabolically healthy individuals7,75,10,11. In this context, exercise may be beneficial to improve peripheral tissue insulin sensitivity following surgery induced weight loss. Recently, a number of studies have examined whether an exercise training intervention following bariatric surgery provides additional improvements in glycemic control (Table 1). Shah et al., found that a 12-week exercise program following RYGB and gastric banding surgery improved glucose tolerance32. Results from a larger randomized controlled trial indicate that moderate aerobic exercise elicits additional improvements in insulin sensitivity and glucose effectiveness, i.e., the ability of glucose per se to facilitate glucose disposal, along with improved cardiorespiratory fitness during RYGB surgery-induced weight loss. These findings are significant as glucose effectiveness is an important contributor to glucose control76, is an independent predictor of diabetes across race/ethnic groups and varying degrees of obesity, and is reduced with impaired glucose tolerance, diabetes and aging77.

Table 1.

Summary of Exercise Intervention Studies in Bariatric Surgery Patients

| Source | Exercise Modality | Duration | No. of Patients |

Surgical Procedure | Principle Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shah, 2011 | High-Volume Exercise Program (Cycling, treadmill walking, rowing) | 12 weeks | 33 | Gastric Banding & RYGB | Feasible in 50% of participants Improved Cardiovascular Fitness Improved postprandial incremental AUC |

| Stegen, 2011 | Supervised Endurance and Strength Training Program | 4 months | 15 | RYGB | Improved Cardiorespiratory Fitness Improved Strength No effect on body composition |

| Coen, 2015 | Treadmill Walking 120min/wk. | 6 months | 128 | RYGB | Improved Peripheral SI & SG Improved Cardiorespiratory Fitness No effect on Body composition |

| Rothwell, 2014 | Exercise Educational Program Resistance Training and Pilates | 6 weeks | 137 | Gastric Banding | Greater %EWL at 12- but not 36-months for participants who attended >1 session |

| Huck, 2014 | Supervised Resistance Training | 12 weeks | 15 | RYGB | Improved Cardiorespiratory Fitness Improved Strength |

Abbreviations: AUC; Area under the curve, RYGB; Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass, SI; Insulin Sensitivity Index, SG; Glucose Effectiveness, %EWL; percent excess weight loss

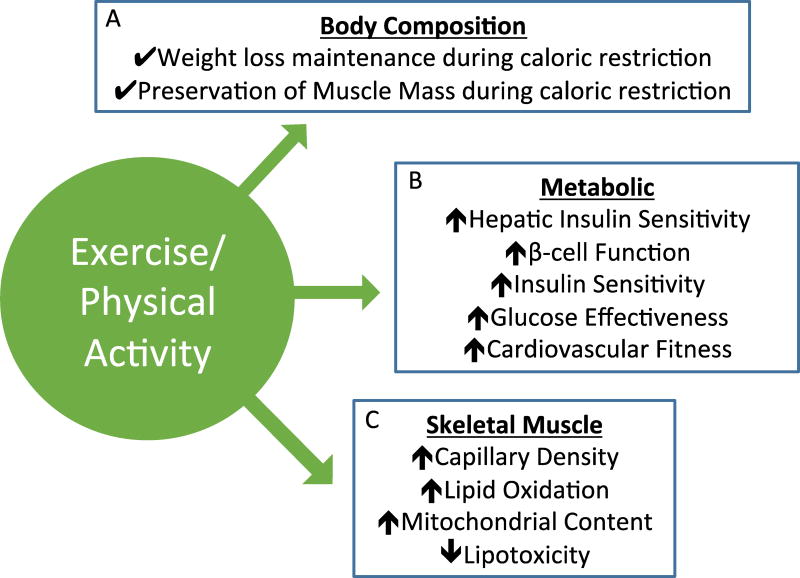

Few studies have examined the myocellular mechanisms of improved muscle insulin sensitivity with surgery induced weight loss, however, reduced ectopic lipid deposition in type I and type II myofibers78 and improvements in mitochondrial function79,80 likely play key roles. Other mechanisms of improved muscle insulin sensitivity are likely similar to those described for calorie restriction induced-weight loss, including reduced inflammation, oxidative stress and improved fatty acid oxidation81,82. The addition of exercise to surgery induced weight loss stimulates increased metabolic flux and unique adaptations that may underlie further improvements in muscle insulin sensitivity (Figure 1). These include angiogenesis and increase capillary density, adaptations that also increase delivery of insulin and glucose to muscle83–85. Exercise also improves fat oxidation in skeletal muscle, mitochondrial function, metabolic flexibility and reduces lipotoxic species including ceramides that are thought to mediate insulin resistance86–88. It is beyond the scope of this review to detail all of these mechanisms, and so the reader is referred to other articles that review myocellular responses to exercise89,90. There is, however, an abundance of evidence that regular exercise elicits a wide array of adaptations that work in concert to improve skeletal muscle insulin sensitivity and glucose control and may also benefit whole body metabolic health via release of myokines into the circulation91. These positive exercise adaptations in conjunction with bariatric surgery induced weight loss likely underlie further improvements in muscle insulin sensitivity and potentially other aspects of whole body health.

Figure 1.

Potential mechanisms by which exercise can impart additional benefit in metabolic health for bariatric surgery patients. A) In the context of diet induced calorie restriction, exercise is effective for weight loss maintenance and preservation of muscle mass. B) Exercise can improve tissue specific and whole body metabolic health. C) Exercise improves skeletal muscle insulin sensitivity by improving mitochondrial bioenergetics and lipid metabolism.

β-cell function and hepatic insulin sensitivity also improve in the weeks following surgery. Studies that used frequently sampled intravenous glucose tolerance (FSIVGT) test to assess intrinsic β-cell function indicate that first phase insulin secretion and disposition index increase in type 2 diabetics one month following RYGB surgery60–62. Indeed, it was recently shown that preoperative β-cell function in patients with type 2 diabetes is important for surgery induced-improvement in β-cell function independent of postprandial release of glucagon-like peptide 1 release92. Again, these are aspects of metabolic function that regular exercise post-surgery may further improve. An 8-month high amount/vigorous intensity exercise program in sedentary overweight adults reduced the acute insulin response and improved disposition index, both indices of β-cell function, when compared to low amount/moderate intensity group93. Others have also shown that exercise can improve β-cell function94. Regular exercise can also improve hepatic insulin sensitivity95,96, potentially via reduction in intrahepatic lipid content97. When exercise was administered with caloric restriction, the intervention was better at reversing free fatty acid induced hepatic insulin resistance, when compared to an eucaloric exercise intervention98. Taken together, these studies describe the powerful effect of exercise to improve metabolic health by impacting multiple organ systems (muscle, liver and pancreas/β-cell), which likely provide additive benefit to bariatric surgery induced weight loss.

There have been a small number of exercise intervention studies in bariatric surgery patients that that have examined other aspects of health (Table 1), including cardiorespiratory fitness, an important cardiometabolic risk factor that is associated with risk of all-cause mortality116. Stegen et al., showed that a 4-month strength/endurance can improve cardiorespiratory fitness and physical function117, a finding that might have implications for older participants who undergo bariatric surgery. Coen et al. also showed that a moderate aerobic exercise intervention (6 months/walking) improved fitness in obese non-diabetic bariatric surgery patients31. Huck et al., reported that resistance training can improve cardiorespiratory fitness and muscle strength in bariatric surgery patients118. This evidence suggests that exercise is feasible for bariatric surgery patients and provides improvements in fitness and muscle strength in addition to the benefits of bariatric surgery-induced weight loss, data that strongly advocate for the inclusion of an exercise program to optimize health benefits during active weight loss following bariatric surgery.

How Physically Active Are Bariatric Surgery Patients?

Given the clear potential for exercise as an adjunct therapeutic option to bariatric surgery, the question arises: do bariatric surgery patients exercise? And do they exercise enough to elicit benefits in health? The physical activity habits of bariatric surgery patients have not been clearly described. A number of studies have compared psychosocial behaviors following substantial weight loss with bariatric surgery and dietary caloric restriction, and indicate that surgery patients have unique eating and physical activity behaviors. A case-controlled study by Klem et al., used data from the NWCR and compared gender, weight and weight loss matched surgery versus non-surgery weight loss subjects103. They found that surgical cases reported significantly lower kcals expended by medium and high intensity physical activity. A second case controlled study by Bond et al., also utilized data from the NWCR, found that surgical participants expended fewer overall calories through physical activity and particularly during high intensity activity104. A secondary analysis was conducted by splitting physical activity caloric expenditure into two categories (0–2000 and >2000 kcal) based on American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) exercise guidelines for weight loss maintenance105. The results showed that a significantly smaller percentage of surgical participants (33%) compared to non-surgical participants (62%) reported expending >2000kcal per week104. Given the low level of physical activity reported, it is doubtful that there is any metabolic benefit being imparted to the patient.

A handful of studies have objectively measured physical activity in bariatric surgery patients using accelerometers or pedometers with mixed results (Table 2)111–114. Among the most thorough examination to date on PA levels following bariatric surgery, King et al. examined data from 310 participants in the Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery-2 study who wore an activity monitor for ≥10hr/day for ≥3days pre- and 1-year post-surgery114. Overall, these participant increased PA by 1457 steps/day, however, there was a wide variation in change (from 7648 fewer steps/day to an increase of 17,205 steps/day). Furthermore, they engaged in a median of 23 high-cadence min/wk. in bouts of ≥10 mins, and only 11% reached ≥150 high-cadence min/wk. in bouts of ≥10 mins following surgery. Conversely, and depending on the PA variable examined, between 23.6 and 29% of participants were ≥5% less active 1-year post surgery, compared to pre-surgery. These data tell us that there is massive variation in change in PA following surgery, with a majority not increasing PA and some even decreasing PA. Importantly, all of the studies that objectively measured PA suggest that the majority of patients accrue significantly less than the 150min/wk. recommended in the physical activity guidelines by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) and likely do not derive any metabolic benefit.

Table 2.

Summary of Studies that Objectively Quantified Free Living Physical Activity in Bariatric Surgery Patients

| Source | Methodology | Time Point | No. of Patients |

Surgical Procedure | Principle Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bond, 2010 | Accelerometers Paffenbarger PA Questionnaire | Pre- & 6 months post-Op | 20 | Gastric Band (65%) RYGB (35%) | Non-significant decreases in MVPA Change in objectively measured moderate/vigorous intensity PA is less than self-reported change |

| Chapman, 2014 | Ankle Pedometer Tri-Axial Accelerometer | 12–18 months post-GB 6–18 months post-SG | 40 | Gastric Band (62.5%) Sleeve Gastrectomy (37.5%) | ~5% of time in MVPA Median daily step count was 9108±4360 |

| Josobeno, 2011 | Tri-Axial Accelerometer | 2–5 years post-Op | 40 | RYGB | %EWL was associated with MVPA |

| King, 2012 | Wrist Accelerometer | Pre-op & 1 year post-Op | 310 | RYGB (69.0%) Gastric Band (21.6%) | PA increased significantly post-Op Wide variation in change in PA 24–29% of participants were ≥5% less PA post-Op |

Abbreviations: RYGB; Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass, %EWL; percent excess weight loss, Moderate-to-Vigorous Physical Activity; MVPA, PA; Physical Activity, SG; Sleeve Gastrectomy, GB; Gastric Banding

Unanswered Questions and Future Directions.

There are number of pertinent questions that remain unanswered relating to the clinical and physiological role of exercise following bariatric surgery:

What is a feasible and effective physical activity intervention following surgery in terms of dose (duration and intensity) and modality (walking, swimming, cycling)?

Does increased exercise/PA provide additive weight loss or fat mass loss, particularly visceral fat, following bariatric surgery?

Is regular exercise an important factor for long-term weight loss maintenance following bariatric surgery?

Does exercise/PA target specific health risks (co-morbidities) in the post bariatric surgery population? Do these occur independent of change in weight of body composition?

Loss of lean mass, including muscle and bone, following surgery may have detrimental consequences on physical function and mobility in older adults and may impact energy expenditure and predispose weight regain.

Does exercise following surgery preserve lean muscle mass in specific subgroups of surgery patients, for example 1) those who rapidly lose weight (and lean mass) following surgery 2) elderly subjects who may be prone to greater loss of lean mass following surgery compared to young.

Does exercise following bariatric surgery improve muscle function, reduce osteoarthritis, knee pain, and improve quality of life in older adults?

Summary.

Obesity, severe obesity and associated co-morbidities are long term and major healthcare problems in the U.S. and worldwide. Bariatric surgery is the most effective treatment option for many but the benefits are not universal to all patients. Furthermore, the long term (>1 year) effectiveness of bariatric surgery still remains unclear. Exercise clearly elicits a multitude of beneficial health effects. We now have objective evidence that bariatric surgery patients are not very physically active and thus represent a patient population who may benefit greatly from exercise. Further randomized controlled trials are now needed as the next step to more clearly define the exercise dose/intensity needed to provide additional health benefits following bariatric surgery and to elucidate the mechanisms by which these improvements are mediated. This valuable evidence will also inform clinical practice regarding much-needed guidelines for exercise following bariatric surgery.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the members of the Goodpaster/Coen laboratory for stimulating discussions on the topics of exercise and bariatric surgery. This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institute on Ageing (AG044437, PMC) and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (DK078192, BHG).

References

- 1.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999–2010. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2012;307(5):491–497. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity among adults: United States, 2011–2012. NCHS data brief. 2013;(131):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Y, Beydoun MA, Liang L, Caballero B, Kumanyika SK. Will all Americans become overweight or obese? estimating the progression and cost of the US obesity epidemic. Obesity. 2008;16(10):2323–2330. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2014;311(8):806–814. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breymaier S. The American Medical Association Adopts New Policies on Second Day of Voting at Annual Meeting. [Accessed 2013-06-18, 2013];2013 Press Release. Available at: http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/news/news/2013/2013-06-18-new-ama-policies-annual-meeting.page.

- 6.Guh DP, Zhang W, Bansback N, Amarsi Z, Birmingham CL, Anis AH. The incidence of co-morbidities related to obesity and overweight: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC public health. 2009;9:88. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang YC, McPherson K, Marsh T, Gortmaker SL, Brown M. Health and economic burden of the projected obesity trends in the USA and the UK. Lancet. 2011;378(9793):815–825. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60814-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McElroy SL, Kotwal R, Malhotra S, Nelson EB, Keck PE, Nemeroff CB. Are mood disorders and obesity related? A review for the mental health professional. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2004;65(5):634–651. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0507. quiz 730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flegal KM, Kit BK, Orpana H, Graubard BI. Association of all-cause mortality with overweight and obesity using standard body mass index categories: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2013;309(1):71–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.113905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Circulation. 2014;129(25 Suppl 2):S102–138. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437739.71477.ee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hill AJ. Does dieting make you fat? The British journal of nutrition. 2004;92(Suppl 1):S15–18. doi: 10.1079/bjn20041135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults--The Evidence Report. National Institutes of Health. Obesity research. 1998;6(Suppl 2):51S–209S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yanovski SZ, Yanovski JA. Long-term drug treatment for obesity: a systematic and clinical review. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2014;311(1):74–86. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Puzziferri N, Roshek TB, 3rd, Mayo HG, Gallagher R, Belle SH, Livingston EH. Long-term follow-up after bariatric surgery: a systematic review. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2014;312(9):934–942. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.10706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schauer PR, Burguera B, Ikramuddin S, et al. Effect of laparoscopic Roux-en Y gastric bypass on type 2 diabetes mellitus. Annals of surgery. 2003;238(4):467–484. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000089851.41115.1b. discussion 484-465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buchwald H, Estok R, Fahrbach K, et al. Weight and type 2 diabetes after bariatric surgery: systematic review and meta-analysis. The American journal of medicine. 2009;122(3):248–256. e245. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schauer PR, Kashyap SR, Wolski K, et al. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy in obese patients with diabetes. The New England journal of medicine. 2012;366(17):1567–1576. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jakicic JM. The effect of physical activity on body weight. Obesity. 2009;17(Suppl 3):S34–38. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pories WJ. Bariatric surgery: risks and rewards. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2008;93(11 Suppl 1):S89–96. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wittgrove AC, Clark GW. Laparoscopic gastric bypass, Roux-en-Y- 500 patients: technique and results, with 3–60 month follow-up. Obesity surgery. 2000;10(3):233–239. doi: 10.1381/096089200321643511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pories WJ, Swanson MS, MacDonald KG, et al. Who would have thought it? An operation proves to be the most effective therapy for adult-onset diabetes mellitus. Annals of surgery. 1995;222(3):339–350. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199509000-00011. discussion 350-332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, et al. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;292(14):1724–1737. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.14.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sugerman HJ, Kellum JM, Engle KM, et al. Gastric bypass for treating severe obesity. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 1992;55(2 Suppl):560S–566S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/55.2.560s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yale CE. Gastric surgery for morbid obesity. Complications and long-term weight control. Archives of surgery. 1989;124(8):941–946. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1989.01410080077012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.te Riele WW, Boerma D, Wiezer MJ, Borel Rinkes IH, van Ramshorst B. Long-term results of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding in patients lost to follow-up. The British journal of surgery. 2010;97(10):1535–1540. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Melton GB, Steele KE, Schweitzer MA, Lidor AO, Magnuson TH. Suboptimal weight loss after gastric bypass surgery: correlation of demographics, comorbidities, and insurance status with outcomes. Journal of gastrointestinal surgery : official journal of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract. 2008;12(2):250–255. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0427-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ochner CN, Teixeira J, Geary N, Asarian L. Greater short-term weight loss in women 20–45 versus 55–65 years of age following bariatric surgery. Obesity surgery. 2013;23(10):1650–1654. doi: 10.1007/s11695-013-0984-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wimmelmann CL, Dela F, Mortensen EL. Psychological predictors of weight loss after bariatric surgery: a review of the recent research. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2014;8(4):e299–313. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peterson MJ, Giuliani C, Morey MC, et al. Physical activity as a preventative factor for frailty: the health, aging, and body composition study. The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2009;64(1):61–68. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gln001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goodpaster BH, Delany JP, Otto AD, et al. Effects of diet and physical activity interventions on weight loss and cardiometabolic risk factors in severely obese adults: a randomized trial. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;304(16):1795–1802. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coen PM, Tanner CJ, Helbling NL, et al. Clinical trial demonstrates exercise following bariatric surgery improves insulin sensitivity. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2015;125(1):248–257. doi: 10.1172/JCI78016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shah M, Snell PG, Rao S, et al. High-volume exercise program in obese bariatric surgery patients: a randomized, controlled trial. Obesity. 2011;19(9):1826–1834. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rothwell L, Kow L, Toouli J. Effect of a Post-operative Structured Exercise Programme on Short-Term Weight Loss After Obesity Surgery Using Adjustable Gastric Bands. Obesity surgery. 2015;25(1):126–128. doi: 10.1007/s11695-014-1323-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goedecke JH, Micklesfield LK. The effect of exercise on obesity, body fat distribution and risk for type 2 diabetes. Med Sport Sci. 2014;60:82–93. doi: 10.1159/000357338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Item F, Konrad D. Visceral fat and metabolic inflammation: the portal theory revisited. Obesity reviews : an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2012;13(Suppl 2):30–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2012.01035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ross R, Dagnone D, Jones PJ, et al. Reduction in obesity and related comorbid conditions after diet-induced weight loss or exercise-induced weight loss in men. A randomized, controlled trial. Annals of internal medicine. 2000;133(2):92–103. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-2-200007180-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ross R, Janssen I, Dawson J, et al. Exercise-induced reduction in obesity and insulin resistance in women: a randomized controlled trial. Obesity research. 2004;12(5):789–798. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coker RH, Williams RH, Yeo SE, et al. The impact of exercise training compared to caloric restriction on hepatic and peripheral insulin resistance in obesity. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2009;94(11):4258–4266. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chaston TB, Dixon JB, O'Brien PE. Changes in fat-free mass during significant weight loss: a systematic review. International journal of obesity. 2007;31(5):743–750. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marks BL, Rippe JM. The importance of fat free mass maintenance in weight loss programmes. Sports medicine. 1996;22(5):273–281. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199622050-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Muller MJ, Bosy-Westphal A, Kutzner D, Heller M. Metabolically active components of fat-free mass and resting energy expenditure in humans: recent lessons from imaging technologies. Obesity reviews : an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2002;3(2):113–122. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-789x.2002.00057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Faria SL, Kelly E, Faria OP. Energy expenditure and weight regain in patients submitted to Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obesity surgery. 2009;19(7):856–859. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-9842-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miller SL, Wolfe RR. The danger of weight loss in the elderly. The journal of nutrition, health & aging. 2008;12(7):487–491. doi: 10.1007/BF02982710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Churchward-Venne TA, Tieland M, Verdijk LB, et al. There Are No Nonresponders to Resistance-Type Exercise Training in Older Men and Women. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(5):400–411. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.01.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Janssen I, Fortier A, Hudson R, Ross R. Effects of an energy-restrictive diet with or without exercise on abdominal fat, intermuscular fat, and metabolic risk factors in obese women. Diabetes care. 2002;25(3):431–438. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.3.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Janssen I, Ross R. Effects of sex on the change in visceral, subcutaneous adipose tissue and skeletal muscle in response to weight loss. International journal of obesity and related metabolic disorders : journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 1999;23(10):1035–1046. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rice B, Janssen I, Hudson R, Ross R. Effects of aerobic or resistance exercise and/or diet on glucose tolerance and plasma insulin levels in obese men. Diabetes care. 1999;22(5):684–691. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.5.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Metcalf B, Rabkin RA, Rabkin JM, Metcalf LJ, Lehman-Becker LB. Weight loss composition: the effects of exercise following obesity surgery as measured by bioelectrical impedance analysis. Obesity surgery. 2005;15(2):183–186. doi: 10.1381/0960892053268381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shah M, Simha V, Garg A. Review: long-term impact of bariatric surgery on body weight, comorbidities, and nutritional status. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2006;91(11):4223–4231. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sjostrom L, Lindroos AK, Peltonen M, et al. Lifestyle, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk factors 10 years after bariatric surgery. The New England journal of medicine. 2004;351(26):2683–2693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Karmali S, Brar B, Shi X, Sharma AM, de Gara C, Birch DW. Weight recidivism post-bariatric surgery: a systematic review. Obesity surgery. 2013;23(11):1922–1933. doi: 10.1007/s11695-013-1070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wing RR. Behavioral weight control. In: Wadden TA, Stunkard AJ, editors. Handbook of Obesity Treatment. New York: The Gilford Press; 2002. pp. 301–316. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jakicic JM, Marcus BH, Lang W, Janney C. Effect of exercise on 24-month weight loss maintenance in overweight women. Archives of internal medicine. 2008;168(14):1550–1559. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.14.1550. discussion 1559–1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wing RR, Hill JO. Successful weight loss maintenance. Annual review of nutrition. 2001;21:323–341. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.21.1.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jakicic JM, Marcus BH, Gallagher KI, Napolitano M, Lang W. Effect of exercise duration and intensity on weight loss in overweight, sedentary women: a randomized trial. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;290(10):1323–1330. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.10.1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schoeller DA, Shay K, Kushner RF. How much physical activity is needed to minimize weight gain in previously obese women? The American journal of clinical nutrition. 1997;66(3):551–556. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/66.3.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Campos GM, Rabl C, Peeva S, et al. Improvement in peripheral glucose uptake after gastric bypass surgery is observed only after substantial weight loss has occurred and correlates with the magnitude of weight lost. Journal of gastrointestinal surgery : official journal of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract. 2010;14(1):15–23. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-1060-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lin E, Phillips LS, Ziegler TR, et al. Increases in adiponectin predict improved liver, but not peripheral, insulin sensitivity in severely obese women during weight loss. Diabetes. 2007;56(3):735–742. doi: 10.2337/db06-1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dunn JP, Abumrad NN, Breitman I, et al. Hepatic and peripheral insulin sensitivity and diabetes remission at 1 month after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery in patients randomized to omentectomy. Diabetes care. 2012;35(1):137–142. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lin E, Davis SS, Srinivasan J, et al. Dual mechanism for type-2 diabetes resolution after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. The American surgeon. 2009;75(6):498–502. discussion 502-493. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Garcia-Fuentes E, Garcia-Almeida JM, Garcia-Arnes J, et al. Morbidly obese individuals with impaired fasting glucose have a specific pattern of insulin secretion and sensitivity: effect of weight loss after bariatric surgery. Obesity surgery. 2006;16(9):1179–1188. doi: 10.1381/096089206778392383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Reed MA, Pories WJ, Chapman W, et al. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass corrects hyperinsulinemia implications for the remission of type 2 diabetes. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2011;96(8):2525–2531. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Falken Y, Hellstrom PM, Holst JJ, Naslund E. Changes in glucose homeostasis after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery for obesity at day three, two months, and one year after surgery: role of gut peptides. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2011;96(7):2227–2235. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rodieux F, Giusti V, D'Alessio DA, Suter M, Tappy L. Effects of gastric bypass and gastric banding on glucose kinetics and gut hormone release. Obesity. 2008;16(2):298–305. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Umeda LM, Silva EA, Carneiro G, Arasaki CH, Geloneze B, Zanella MT. Early improvement in glycemic control after bariatric surgery and its relationships with insulin, GLP-1, and glucagon secretion in type 2 diabetic patients. Obesity surgery. 2011;21(7):896–901. doi: 10.1007/s11695-011-0412-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Beckman LM, Beckman TR, Earthman CP. Changes in gastrointestinal hormones and leptin after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass procedure: a review. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2010;110(4):571–584. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kashyap SR, Daud S, Kelly KR, et al. Acute effects of gastric bypass versus gastric restrictive surgery on beta-cell function and insulinotropic hormones in severely obese patients with type 2 diabetes. International journal of obesity. 2010;34(3):462–471. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2009.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pournaras DJ, Aasheim ET, Sovik TT, et al. Effect of the definition of type II diabetes remission in the evaluation of bariatric surgery for metabolic disorders. The British journal of surgery. 2012;99(1):100–103. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Isbell JM, Tamboli RA, Hansen EN, et al. The importance of caloric restriction in the early improvements in insulin sensitivity after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Diabetes care. 2010;33(7):1438–1442. doi: 10.2337/dc09-2107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Goodpaster BH, Thaete FL, Kelley DE. Thigh adipose tissue distribution is associated with insulin resistance in obesity and in type 2 diabetes mellitus. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2000;71(4):885–892. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.4.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Goodpaster BH, Thaete FL, Simoneau JA, Kelley DE. Subcutaneous abdominal fat and thigh muscle composition predict insulin sensitivity independently of visceral fat. Diabetes. 1997;46(10):1579–1585. doi: 10.2337/diacare.46.10.1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Toledo FG, Menshikova EV, Azuma K, et al. Mitochondrial capacity in skeletal muscle is not stimulated by weight loss despite increases in insulin action and decreases in intramyocellular lipid content. Diabetes. 2008;57(4):987–994. doi: 10.2337/db07-1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Olbers T, Bjorkman S, Lindroos A, et al. Body composition, dietary intake, and energy expenditure after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and laparoscopic vertical banded gastroplasty: a randomized clinical trial. Annals of surgery. 2006;244(5):715–722. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000218085.25902.f8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tamboli RA, Hossain HA, Marks PA, et al. Body composition and energy metabolism following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Obesity. 2010;18(9):1718–1724. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Camastra S, Gastaldelli A, Mari A, et al. Early and longer term effects of gastric bypass surgery on tissue-specific insulin sensitivity and beta cell function in morbidly obese patients with and without type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2011;54(8):2093–2102. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2193-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Best JD, Kahn SE, Ader M, Watanabe RM, Ni TC, Bergman RN. Role of glucose effectiveness in the determination of glucose tolerance. Diabetes care. 1996;19(9):1018–1030. doi: 10.2337/diacare.19.9.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lorenzo C, Wagenknecht LE, Rewers MJ, et al. Disposition index, glucose effectiveness, and conversion to type 2 diabetes: the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study (IRAS) Diabetes care. 2010;33(9):2098–2103. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gray RE, Tanner CJ, Pories WJ, MacDonald KG, Houmard JA. Effect of weight loss on muscle lipid content in morbidly obese subjects. American journal of physiology. Endocrinology and metabolism. 2003;284(4):E726–732. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00371.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nijhawan S, Richards W, O'Hea MF, Audia JP, Alvarez DF. Bariatric surgery rapidly improves mitochondrial respiration in morbidly obese patients. Surg Endosc. 2013;27(12):4569–4573. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3125-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vijgen GH, Bouvy ND, Hoeks J, Wijers S, Schrauwen P, van Marken Lichtenbelt WD. Impaired skeletal muscle mitochondrial function in morbidly obese patients is normalized one year after bariatric surgery. Surgery for obesity and related diseases : official journal of the American Society for Bariatric Surgery. 2013;9(6):936–941. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Redman LM, Ravussin E. Caloric restriction in humans: impact on physiological, psychological, and behavioral outcomes. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2011;14(2):275–287. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Spindler SR. Caloric restriction: from soup to nuts. Ageing research reviews. 2010;9(3):324–353. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lillioja S, Young AA, Culter CL, et al. Skeletal muscle capillary density and fiber type are possible determinants of in vivo insulin resistance in man. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1987;80(2):415–424. doi: 10.1172/JCI113088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Marin P, Andersson B, Krotkiewski M, Bjorntorp P. Muscle fiber composition and capillary density in women and men with NIDDM. Diabetes care. 1994;17(5):382–386. doi: 10.2337/diacare.17.5.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rasio E. The capillary barrier to circulating insulin. Diabetes care. 1982;5(3):158–161. doi: 10.2337/diacare.5.3.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Dube JJ, Amati F, Stefanovic-Racic M, Toledo FG, Sauers SE, Goodpaster BH. Exercise-induced alterations in intramyocellular lipids and insulin resistance: the athlete's paradox revisited. American journal of physiology. Endocrinology and metabolism. 2008;294(5):E882–888. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00769.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dube JJ, Amati F, Toledo FG, et al. Effects of weight loss and exercise on insulin resistance, and intramyocellular triacylglycerol, diacylglycerol and ceramide. Diabetologia. 2011;54(5):1147–1156. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2065-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Goodpaster BH, Katsiaras A, Kelley DE. Enhanced fat oxidation through physical activity is associated with improvements in insulin sensitivity in obesity. Diabetes. 2003;52(9):2191–2197. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.9.2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Egan B, Zierath JR. Exercise metabolism and the molecular regulation of skeletal muscle adaptation. Cell metabolism. 2013;17(2):162–184. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hawley JA, Lessard SJ. Exercise training-induced improvements in insulin action. Acta physiologica. 2008;192(1):127–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2007.01783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bostrom PA, Graham EL, Georgiadi A, Ma X. Impact of exercise on muscle and nonmuscle organs. IUBMB life. 2013;65(10):845–850. doi: 10.1002/iub.1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lund MT, Hansen M, Skaaby S, et al. Preoperative beta-cell function in patients with type 2 diabetes is important for the outcome of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. The Journal of physiology. 2015 doi: 10.1113/JP270264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Slentz CA, Tanner CJ, Bateman LA, et al. Effects of exercise training intensity on pancreatic beta-cell function. Diabetes care. 2009;32(10):1807–1811. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bloem CJ, Chang AM. Short-term exercise improves beta-cell function and insulin resistance in older people with impaired glucose tolerance. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2008;93(2):387–392. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Malin SK, del Rincon JP, Huang H, Kirwan JP. Exercise-induced lowering of fetuin-A may increase hepatic insulin sensitivity. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2014;46(11):2085–2090. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Malin SK, Haus JM, Solomon TP, Blaszczak A, Kashyap SR, Kirwan JP. Insulin sensitivity and metabolic flexibility following exercise training among different obese insulin-resistant phenotypes. American journal of physiology. Endocrinology and metabolism. 2013;305(10):E1292–1298. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00441.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Finucane FM, Sharp SJ, Purslow LR, et al. The effects of aerobic exercise on metabolic risk, insulin sensitivity and intrahepatic lipid in healthy older people from the Hertfordshire Cohort Study: a randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia. 2010;53(4):624–631. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1641-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Haus JM, Solomon TP, Marchetti CM, Edmison JM, Gonzalez F, Kirwan JP. Free fatty acid-induced hepatic insulin resistance is attenuated following lifestyle intervention in obese individuals with impaired glucose tolerance. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2010;95(1):323–327. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Bacchi E, Negri C, Zanolin ME, et al. Metabolic effects of aerobic training and resistance training in type 2 diabetic subjects: a randomized controlled trial (the RAED2 study) Diabetes care. 2012;35(4):676–682. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Duncan GE, Perri MG, Theriaque DW, Hutson AD, Eckel RH, Stacpoole PW. Exercise training, without weight loss, increases insulin sensitivity and postheparin plasma lipase activity in previously sedentary adults. Diabetes care. 2003;26(3):557–562. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.3.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sigal RJ, Kenny GP, Boule NG, et al. Effects of aerobic training, resistance training, or both on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes: a randomized trial. Annals of internal medicine. 2007;147(6):357–369. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-6-200709180-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Frosig C, Richter EA. Improved insulin sensitivity after exercise: focus on insulin signaling. Obesity. 2009;17(Suppl 3):S15–20. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Klem ML, Wing RR, Chang CC, et al. A case-control study of successful maintenance of a substantial weight loss: individuals who lost weight through surgery versus those who lost weight through non-surgical means. International journal of obesity and related metabolic disorders : journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2000;24(5):573–579. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bond DS, Phelan S, Leahey TM, Hill JO, Wing RR. Weight-loss maintenance in successful weight losers: surgical vs non-surgical methods. International journal of obesity. 2009;33(1):173–180. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Jakicic JM, Clark K, Coleman E, et al. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Appropriate intervention strategies for weight loss and prevention of weight regain for adults. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2001;33(12):2145–2156. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200112000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Egberts K, Brown WA, Brennan L, O'Brien PE. Does exercise improve weight loss after bariatric surgery? A systematic review. Obesity surgery. 2012;22(2):335–341. doi: 10.1007/s11695-011-0544-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Livhits M, Mercado C, Yermilov I, et al. Behavioral factors associated with successful weight loss after gastric bypass. The American surgeon. 2010;76(10):1139–1142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Chevallier JM, Paita M, Rodde-Dunet MH, et al. Predictive factors of outcome after gastric banding: a nationwide survey on the role of center activity and patients' behavior. Annals of surgery. 2007;246(6):1034–1039. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31813e8a56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Evans RK, Bond DS, Wolfe LG, et al. Participation in 150 min/wk of moderate or higher intensity physical activity yields greater weight loss after gastric bypass surgery. Surgery for obesity and related diseases : official journal of the American Society for Bariatric Surgery. 2007;3(5):526–530. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Colles SL, Dixon JB, O'Brien PE. Hunger control and regular physical activity facilitate weight loss after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Obesity surgery. 2008;18(7):833–840. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9409-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bond DS, Jakicic JM, Unick JL, et al. Pre- to postoperative physical activity changes in bariatric surgery patients: self report vs. objective measures. Obesity. 2010;18(12):2395–2397. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Chapman N, Hill K, Taylor S, Hassanali M, Straker L, Hamdorf J. Patterns of physical activity and sedentary behavior after bariatric surgery: an observational study. Surgery for obesity and related diseases : official journal of the American Society for Bariatric Surgery. 2014;10(3):524–530. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2013.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Josbeno DA, Kalarchian M, Sparto PJ, Otto AD, Jakicic JM. Physical activity and physical function in individuals post-bariatric surgery. Obesity surgery. 2011;21(8):1243–1249. doi: 10.1007/s11695-010-0327-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.King WC, Hsu JY, Belle SH, et al. Pre- to postoperative changes in physical activity: report from the longitudinal assessment of bariatric surgery-2 (LABS-2) Surgery for obesity and related diseases : official journal of the American Society for Bariatric Surgery. 2012;8(5):522–532. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2011.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Coen PM, Tanner CJ, Helbling NL, et al. Clinical trial demonstrates exercise following bariatric surgery improves insulin sensitivity. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2014 doi: 10.1172/JCI78016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Farrell SW, Braun L, Barlow CE, Cheng YJ, Blair SN. The relation of body mass index, cardiorespiratory fitness, and all-cause mortality in women. Obesity research. 2002;10(6):417–423. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Stegen S, Derave W, Calders P, Van Laethem C, Pattyn P. Physical fitness in morbidly obese patients: effect of gastric bypass surgery and exercise training. Obesity surgery. 2011;21(1):61–70. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-0045-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Huck CJ. Effects of Supervised Resistance Training on Fitness And Functional Strength in Patients Succeeding Bariatric Surgery. Journal of strength and conditioning research / National Strength & Conditioning Association. 2014 doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.King WC, Bond DS. The importance of preoperative and postoperative physical activity counseling in bariatric surgery. Exercise and sport sciences reviews. 2013;41(1):26–35. doi: 10.1097/JES.0b013e31826444e0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Mechanick JI, Kushner RF, Sugerman HJ, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, The Obesity Society, and American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery medical guidelines for clinical practice for the perioperative nutritional, metabolic, and nonsurgical support of the bariatric surgery patient. Obesity. 2009;17(Suppl 1):S1–70. v. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Baillot A, Asselin M, Comeau E, Meziat-Burdin A, Langlois MF. Impact of excess skin from massive weight loss on the practice of physical activity in women. Obesity surgery. 2013;23(11):1826–1834. doi: 10.1007/s11695-013-0932-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Bond DS, Thomas JG, Unick JL, Raynor HA, Vithiananthan S, Wing RR. Self-reported and objectively measured sedentary behavior in bariatric surgery candidates. Surgery for obesity and related diseases : official journal of the American Society for Bariatric Surgery. 2013;9(1):123–128. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Wouters EJ, Larsen JK, Zijlstra H, van Ramshorst B, Geenen R. Physical activity after surgery for severe obesity: the role of exercise cognitions. Obesity surgery. 2011;21(12):1894–1899. doi: 10.1007/s11695-010-0276-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Peacock JC, Sloan SS, Cripps B. A qualitative analysis of bariatric patients' post-surgical barriers to exercise. Obesity surgery. 2014;24(2):292–298. doi: 10.1007/s11695-013-1088-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]