Abstract

Terpenes make up the largest and most diverse class of natural compounds and have important commercial and medical applications. Limonene is a cyclic monoterpene (C10) present in nature as two enantiomers, (+) and (−), which are produced by different enzymes. The mechanism of production of the (−)-enantiomer has been studied in great detail, but to understand how enantiomeric selectivity is achieved in this class of enzymes, it is important to develop a thorough biochemical description of enzymes that generate (+)-limonene, as well. Here we report the first cloning and biochemical characterization of a (+)-limonene synthase from navel orange (Citrus sinensis). The enzyme obeys classical Michaelis–Menten kinetics and produces exclusively the (+)-enantiomer. We have determined the crystal structure of the apoprotein in an “open” conformation at 2.3 Å resolution. Comparison with the structure of (−)-limonene synthase (Mentha spicata), which is representative of a fully closed conformation (Protein Data Bank entry 2ONG), reveals that the short H-α1 helix moves nearly 5 Å inward upon substrate binding, and a conserved Tyr flips to point its hydroxyl group into the active site.

Graphical abstract

Terpenes make up the largest and most structurally diverse class of natural products.1 They are secondary metabolites involved in a host of functions in many different biological systems. Plants in particular have developed a diverse array of terpenes that serve as signaling hormones, as chemical defense agents against microbial infection and predation, and as attractants for pollinators.1 Terpenes also play important industrial roles as solvents, fragrances, flavorings, and materials, and many have pharmaceutical applications. Despite their structural and functional diversity, most terpenes are derived from only three simple acyclic precursors: C10 monoterpenes from geranyl diphosphate (GPP), C15 sesquiterpenes from farnesyl diphosphate (FPP), and C20 diterpenes from geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP).

The committed step in terpene biosynthesis generally involves conversion of the acyclic isoprenoid diphosphate precursor to cyclic hydrocarbon products through the action of enzymes known as terpene synthases (or cyclases).2–7 The divalent metal ion (typically Mn2+ or Mg2+) dependent reaction in class 1 cyclases8 is initiated by ionization of the diphosphate precursor to generate a high-energy, allylic carbenium ion intermediate.9 The synthase then controls the reactivity of this intermediate to generate a vast array of different products that can result from carbon skeleton rearrangements as well as methyl and hydride shifts.9

One of the simplest cyclization reactions is catalyzed by limonene synthase (Figure 1).6 Limonene is a cyclic monoterpene that is present in nature as two enantiomers, (+) and (−), which are produced by different enzymes. The proposed cyclization reaction for limonene synthase (as for all monoterpene synthases) begins with stereoselective binding of GPP to the enzyme as a right-handed or left-handed conformer, depending on the stereochemistry of the resulting product.10 The diphosphate moiety then dissociates, forming a resonance-stabilized carbenium ion intermediate. The diphosphate is believed to reattach at the tertiary C3 to form either (3R)- or (3S)-linalyl diphosphate (LPP), allowing rotation about the C2–C3 bond to place C1 in a position permitting cyclization with C6. All monoterpenes are thought to proceed through the common α-terpinyl cation, and the resulting skeletal diversity of the monoterpenes is dictated by termination of the reaction, which can involve deprotonation of a methyl group (as is the case for limonene) or nucleophilic attack by water (as is the case for terpineol) followed by release of the cyclic product.6

Figure 1.

Chemical mechanism proposed for the formation of limonene from geranyl diphosphate (GPP).6,11 The stereochemistry of intermediate species is not represented; however, the same mechanism is predicted to form either (+)-(4R)- or (−)-(4S)-limonene depending on the initial folding of GPP in the Michaelis complex and whether (3R)- or (3S)-LPP is formed as an intermediate.

The crystal structure of a (−)-limonene synthase [(−)-LS] has been determined previously after cocrystallization with the substrate analogues 2-fluoro-GPP (FGPP) and 2-fluoro-LPP (FLPP) [Protein Data Bank (PDB) entries 2ONG and 2ONH, respectively].11 These structures revealed that (−)-LS shares many of the hallmark features characteristic of plant monoterpene synthases, including an all-α-helical domain secondary structure, a two-domain architecture with a catalytic C-terminal domain and an N-terminal domain of unknown function, and conserved divalent metal ion binding residues in the active site. Although (−)-LS was cocrystallized with FGPP, electron density in the active site was better fit by modeling in FLPP in an extended configuration, implying that the structure represents a snapshot of the reaction in progress.

We report here the cloning and biochemical characterization of a (+)-limonene synthase [(+)-LS] from navel orange (Citrus sinensis). (+)-Limonene is a highly abundant monoterpene and is the principle terpene constituent of most citrus fruit essential oils.12 While it is commonly used as an industrial and household solvent, its characteristic citrus smell has also made it particularly useful for the fragrance and flavoring industries, and it has noted potential as a renewable biofuel.13 We present the crystal structure of the apoprotein determined at 2.3 Å resolution in an “open” conformation. Comparison of our apo-(+)-LS structure with that of FLPP-bound (−)-LS highlights conformational changes that are likely important for the transition from open apoenzyme to the fully closed substrate-bound form.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Synthesis of Geranyl Diphosphate

GPP was synthesized from geraniol using the large-scale phosphorylation procedure previously described by Keller and Thompson in which geraniol (300 mg) was phosphorylated by reaction with triethylammonium phosphate (TEAP) and trichloroacetonitrile at 37 °C.14 The completed reaction mixture was stored overnight at −20 °C and then separated by flash chromatography on a silica column using a 12:5:1 isopropanol/ammonium hydroxide/water mobile phase. Fractions were analyzed by thin-layer chromatography developed in a 6:3:1 isopropanol/ammonium hydroxide/water mixture and visualized with KMnO4. Fractions containing pure GPP were pooled, concentrated by rotary evaporation at reduced pressure, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and lyophilized to dryness for 18–24 h.

Lyophilized GPP was further purified by anion exchange chromatography using DOWEX-1X2-400 strongly basic anion exchange resin chloride form (Sigma). A 1 cm × 8 cm resin bed was equilibrated with 125 mM ammonium bicarbonate (pH 8), loaded with 10–30 mg of GPP, and washed with 40 mL of 125 mM ammonium bicarbonate at a flow rate of 2 mL/min. The column was then eluted using 500 mM ammonium bicarbonate. Fractions were analyzed on TLC plates and visualized with KMnO4 to locate the eluted GPP that was then flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and lyophilized to dryness for 24–48 h. The lyophilized product was stored at −20 °C until it was needed. The purity was assessed by proton, carbon, and phosphorus nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian 400-MR spectrometer (9.4 T, 400 MHz) in D2O adjusted to pH ~8.0 with ND4OD. 1H and 13C chemical shifts are reported in parts per million downfield from TMSP (trimethylsilyl propionic acid), and 31P chemical shifts are reported in parts per million relative to 85% o-phosphoric acid. J coupling constants are reported in units of frequency (hertz) with multiplicities listed as s (singlet), d (doublet), dd (doublet of doublets), t (triplet), m (multiplet), br (broad), and app (apparent): 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O/ND4OD) δH 1.64 (3 H, s, CH3), 1.70 (3 H, s, CH3), 1.73 (3 H, s, CH3), 2.08–2.20 (4 H, m, H at C4 and C5), 4.48 (2 H, app t, J = 6.6 Hz, JH,P = 6.6 Hz, H at C1), 5.22 (1 H, br t, J = 6.0 Hz, H at C6), 5.47 (1 H, t, J = 7.0 Hz, H at C2); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, D2O/ND4OD) δC 18.45, 19.81, 27.67, 28.45, 41.64, 65.32 (1 C, d, JC,P = 5.34 Hz), 122.90 (1 C, d, JC,P = 8.39 Hz), 127.03, 136.57, 145.43; 31P{1H} NMR (162 MHz, D2O/ND4OD) δP −5.74 (1 P, d, JP,P = 22.1 Hz, P1), −9.55 (1 P, d, JP,P = 22.1 Hz, P2).

Cloning of the C. sinensis (+)-Limonene Synthase Gene

Total RNA was extracted from the flavedo of a navel orange (C. sinensis), purchased at a local supermarket, using the RNeasy Plant Mini kit (Qiagen) under conditions recommended for recalcitrant material. First-strand cDNA synthesis with reverse transcriptase was performed using the Super Script III CellsDirect cDNA Synthesis System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Double-stranded cDNA for the limonene synthase gene was amplified using primers based on the sequence of the published Citrus limon (+)-LS gene (GenBank accession number AF514287), which we expected to be similar to the gene found in navel orange.15 The following primers were used: 5′-CCG tat aag ccg gtc gac g atg tct tct tgc ATT AAT CCC TCA ACC TTG-3′ and 5′-AAA TGA GCG GCC GC TCA GCC TTT GGT GCC AGG AGA TGC TGT-3′. A SalI site was introduced at the 5′-end and a NotI site at the 3′-end to facilitate recovery of DNA from the vector.

Amplified cDNA was cloned into a pCRII-TOPO vector using the TOPO TA Cloning kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The vector was transformed into chemically competent TOP10F’ cells that were then grown overnight at 37 °C on LB/agar plates containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin, 40 μg/mL X-gal, and 100 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). Following blue/white colony screening, colony PCR (using the same primers as used for RT-PCR) was performed to confirm the presence of the gene. The nucleotide sequence has been added to GenBank (accession code KU746814). The cDNA was then truncated at the 5′-end (nucleotides encoding amino acids 1–52) to remove the plastid targeting sequence, modified by addition of an N-terminal His6 tag for purification, and cloned into the NcoI and NotI restriction enzyme-cut sites of a pET-28a (+) expression vector.

Site-directed mutagenesis was performed to substitute the Tyr at position 565 with Phe (Y565F) using the QuikChange II Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies). The following mutagenic primers were designed: Y565F, 5′-GTC CCA TTT TAT GTT TCT ACA TGG AG-3′ and 5′-CTC CAT GTA GAA ACA TAA AAT GGG AC-3′. The nucleotide substitution was verified by sequencing the full construct (Genewiz).

Protein Expression and Purification

The N-terminally His6-tagged and truncated (+)-LS construct was subcloned into the pET-28a (+) vector and transformed into BL21-CodonPlus(DE3)-RIL cells (Agilent Technologies). The transformed cells were selected on LB/agar plates containing 50 μg/ mL kanamycin and 20 μg/mL chloramphenicol following incubation at 37 °C overnight. Single colonies were selected and grown in small overnight cultures (10 mL of LB, again with 50 μg/mL kanamycin and 20 μg/mL chloramphenicol) at 37 °C with 220 rpm shaking overnight. One milliliter of the overnight culture was used to inoculate 1 L of LB (in the absence of antibiotics) and grown at 37 °C until the OD600 was between 0.5 and 0.8, at which time protein expression was induced by addition of IPTG to a final concentration of 1 mM. The temperature was decreased to 20 °C, and after being induced for 20 h, cells were pelleted by centrifugation. Pelleted cells were resuspended in 20 mL of lysis buffer [50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, and 20 mM imidazole] and stored at −80 °C until they were needed.

Frozen cell suspensions were thawed on ice and brought to 50 mL with lysis buffer. DNase I and lysozyme were each added to a final concentration of 10 μg/mL along with five EDTA-free Pierce protease inhibitor cocktail tablets (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The cell suspension was sonicated on ice using a preset cycle of 20 s on and 30 s off for a total of 3 min on-time at roughly 50–100 mW power. Cell debris was pelleted by centrifugation at 9490 rcf for 45 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant fraction was passed through a 0.22 μm filter and then loaded at a rate of 1 mL/min onto a prepacked 5 mL HiTrapFF Ni-Sepharose column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) that had been previously equilibrated in lysis buffer. The column was washed at a rate of 1.5 mL/min with 40 mL of wash buffer (lysis buffer with the imidazole concentration increased to 40 mM) and then eluted with an 80 mL linear gradient ranging from 40 to 500 mM imidazole also at a rate of 1.5 mL/min. Fractions containing (+)-LS were identified via sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and pooled before being concentrated with an exchange of buffer [50 mM Tris (pH 7.5) and 100 mM NaCl] to remove imidazole (50 kDa molecular weight cutoff Amicon Ultra Centrifuge Filter from EMD Millipore).

Size-Exclusion Chromatography

Size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) was conducted using an Äkta FPLC system (Amersham Biosciences, Uppsala, Sweden) equipped with a Superdex-200 10/300 GL gel filtration column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences); 300 μL of 100 μM (+)-LS was loaded onto the column that was equilibrated in 50 mM Tris (pH 8), 100 mM NaCl, and 10% glycerol at 4 °C. The flow was maintained at a constant rate of 0.5 mL/min. The void volume was measured at 8.3 mL by eluting blue dextran as a high-molecular weight standard (MW ~ 2000 kDa). The total internal column volume was measured at 21.19 mL with vitamin B12 as a low-molecular weight standard (MW = 1.35 kDa). These and other well-resolved molecular weight standards were used to derive a standard curve that allowed accurate estimation of the molecular weight of eluted (+)-LS.

Enzymatic Activity Assay

The enzymatic activity was monitored using the discontinuous single-vial assay described by O’Maille et al.16 with the exception that hexane was used for the organic layer rather than ethyl acetate. Each screw-cap vial contained a 1 mL reaction mixture composed of 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 100 mM NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol, the purified protein, GPP, and MnCl2 (400 μM) overlaid with 1 mL of hexane. Reactions were initiated by addition of substrate and allowed to proceed for various times, and mixtures were vortexed for 30 s to both terminate the reaction and extract terpene products into the organic layer. The progress of the reaction was monitored by gas chromatography and mass spectrometry (GC–MS) of samples taken from the hexane layer. Product yields were determined by comparing integrated GC peaks from the reaction mixture to those of a standard curve for (+)-limonene obtained from a commercial source. Reactions were measured under initial rate conditions (linear time course from 2 to 6 min) for a range of substrate concentrations (1–200 μM) under conditions that were also linear with enzyme concentration. The resulting velocity versus substrate concentration data were fit by nonlinear regression (Igor Pro software package, WaveMetrics) with the Michaelis–Menten equation [v = (Vmax[S])/(KM + [S])] to extract the kinetic parameters KM and kcat.

Gas Chromatography and Mass Spectrometry

Hexane extractable terpene products were identified and quantified using GC-MS (Agilent Technologies 7890A GC System coupled with a 5975C VL MSD with a triple-axis detector). Pulsed-splitless injection was used to inject 5 μL samples onto an HP-5ms (5%-phenyl)-methylpolysiloxane capillary GC column (Agilent Technologies, 30 m × 250 μm × 0.25 μm) at an inlet temperature of 220 °C and run at constant pressure using helium as the carrier gas. Samples were initially held at an oven temperature of 50 °C for 1 min, followed by a linear temperature gradient of 13 °C/min to 141 °C and a second linear gradient at 50 °C/min to a final temperature of 240 °C, which was then held for 1 min. Retention times coupled with mass spectra were verified using commercially available terpene standards.

Circular Dichroism

Limonene enantiomeric purity was determined by circular dichroism (CD). CD experiments were conducted using a J-810 spectropolarimeter (Jasco). Limonene was dissolved in hexanes, and measurements were taken using a 1 mm path-length quartz cuvette. A total of 15 accumulations were recorded for each sample. Spectra were recorded from 300 to 185 nm at a bandwidth of 1 nm and a scan speed of 100 nm/min. All spectra were recorded at 25 °C. The enantiomeric purity was determined by comparing the molar ellipticity ([θ], deg*cm2*dmol−1) of the enzymatic sample with that of a commercially sourced (+)-limonene standard (Sigma).

Crystallization

Crystallization trials were set by mixing 15 mg/mL protein in buffer [50 mM Tris (pH 7.5) and 100 mM NaCl] with mother liquor at a 1:1 (v/v) ratio. Initial trials were performed using the sitting drop vapor diffusion method with Jena Bioscience sparse matrix crystallization screens (Jena Bioscience, Jena, Germany). Drops were set with the aid of a Phoenix crystallization robot (Art Robbins Instruments). The hanging drop method was used for further optimizations. Crystals approximately 0.3 mm × 0.4 mm × 0.2 mm in size grew in the presence of 12–16% PEG-8000, 100 mM Tris (pH 7.5–9.0), and 200–350 mM sodium tartrate after 10 days at 20 °C.

Data Collection, Processing, and Refinement

Crystals were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen after being soaked briefly in mother liquor containing 20% glycerol. Data sets were collected at beamline 8.2.1 at the Advanced Light Source (Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA) using ADSC Q315R CCD detectors (Area Detector Systems Corp.) at a temperature of 100 K. The best crystals diffracted to 2.3 Å resolution. The data were indexed and integrated using iMosflm version 7.217 and scaled using SCALA version 3.318 from the CCP4 software suite version 6.4.19,20 Diffraction data were processed in the P41212 space group. The unit cell dimensions were as follows: a = b = 85.8 Å, c = 216.4 Å, and α = β = γ = 90°. Complete data collection statistics are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Crystallographic Data Collection and Refinement Statistics

| PDB entry | 5UV0 | |

|---|---|---|

| Data Collection | ||

| space group | P41212 | |

| resolution range (Å) | 20–2.3 | |

| highest-resolution shell (Å) | 2.42–2.3 | |

| unit cell parameters (Å) | a = b = 85.8, c = 216.4 | |

| total no. of reflections | 762563 | |

| no. of unique reflections | 36820 | |

| completeness (%)a | 99.8 (99.6) | |

| Rmerge(%)a | 10.3 (116) | |

| I/σ(I)a | 17.2 (2.1) | |

| CC(1/2) (%)a | 99.9 (71.6) | |

| redundancya | 20.7 (12.6) | |

| Refinement | ||

| resolution range (Å) | 20–2.3 | |

| no. of reflections used | 36688 | |

| Rcryst (%) | 19.0 | |

| Rfree (%) | 22.9 | |

| no. of protein atoms | 4316 | |

| no. of water molecules | 174 | |

| rmsd for bond lengths (Å) | 0.007 | |

| rmsd for bond angles (deg) | 0.8 |

Values for the highest-resolution shell are given in parentheses.

The structure of (+)-LS was determined by molecular replacement with PHASER21 using the structure of (−)-LS from M. spicata as a search model (PDB entry 2ONG). The molecular replacement solution found one protein monomer in the asymmetric unit. The structure was initially refined to starting R and Rfree values of 0.238 and 0.282, respectively. Refinement was performed using the function phenix.refine22 in the PHENIX software suite version 1.1023 with the initial two positional refinements preceded by rigid body refinement. All model building was done using COOT version 0.8.24

The altered position of the H-α1 helix in the apoprotein structure was rebuilt from the original model, and the disordered residues whose main chain electron density was not observed above a 1σ 2Fo − Fc cutoff were removed from the final model. Spherical solvent peaks above 3σ Fo − Fc and 1σ 2Fo − Fc were identified, and water molecules were modeled in and included in the final rounds of refinement. The final structure was refined to R and Rfree values of 0.190 and 0.229, respectively. The refinement statistics are listed in Table 1. Coordinates and structure factors for the apoprotein (PDB entry 5UV0) data set have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank. All crystal structure figures in this paper were prepared using PyMol version 1.3 (Schrödinger LLC, Portland, OR).

RESULTS

(+)-LS, the (+)-Limonene Synthase from Navel Orange

cDNA for (+)-LS was obtained from the flavedo of a navel orange (see Experimental Procedures). The translated protein sequence consists of 607 amino acids (including Nterminal methionine) with an estimated molecular weight of 70.4 kDa, which places it in the range of other plant monoterpene synthases that typically have two similarly sized domains: an N-terminal domain of unknown function and a C-terminal domain that contains the active site.7 Sequence elements shared by other monoterpene synthases are conserved in (+)-LS, including the plastidial targeting sequence, the Nterminal Arg pair of the mature protein, and acidic divalent metal ion binding sites. Plant synthases often bear a signature N-terminal plastidial targeting sequence of approximately 50–60 residues that is noted for being rich in small polar residues (Ser and Thr) and devoid of charged acidic residues (Asp and Glu) but is otherwise without identifiable sequence conservation.25 The targeting sequence is removed by proteolysis once the synthase has been transported into chloroplasts, and the mature, functional form of the protein is thought to begin with a pair of conserved Arg residues (R53 and R54) at the Nterminus, which are involved in closing off the active site to solvent once substrate has bound. The divalent metal cation binding sites, [DDXXD] and [(N/D)DXX(S/T)XXXE],4 found in the D and H helices, are also present in the orange (+)-LS (D343, D344, D347 and D488, D489, T492, and E496).

A BLAST search of (+)-LS identified the (+)-limonene synthase CitMTSE2 from satsuma mandarin orange (Citrus unshiu)26 as the closest homologue with 99.7% sequence identity. The two sequences differ at only two positions, both in the noncatalytic N-terminal domain: a conservative substitution of Val for Ala and an insertion of a Lys residue in the mandarin orange sequence. The next closest homologue is the (+)-limonene synthase C1(+)LIMS2 from lemon (C. limon)15 with 95.6% amino acid identity, where again most of the sequence differences are in the N-terminal domain. In contrast to the high degree of sequence identity among the citrus fruit (+)-limonene synthases, the sequence of (+)-LS is only 44.7% identical to that of the (−)-LS from spearmint (M. spicata),27 although the residues lining the active site are mostly conserved (Figure S1; see also Figure 7).

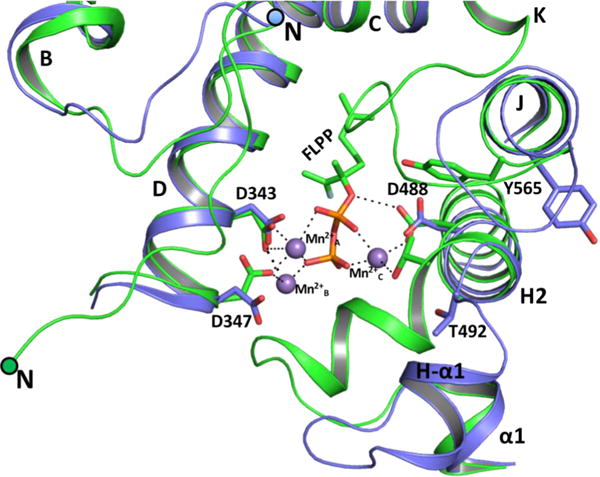

Figure 7.

Similarity of amino acid residues in the active site binding pocket of apo-(+)-LS (blue) and FLPP-bound (−)-LS (green, PDB entry 2ONG) structures. The substrate analogue and J–K loop have been removed for the sake of clarity. Residues are numbered according to the (+)-LS sequence. In the case in which sequences diverge, the single-letter amino acid code following the forward slash corresponds to the (−)-LS structure.

Purification

Recombinant expression of plant terpene synthases has been shown to be improved by truncation of the full-length proteins to remove the N-terminal plastidial targeting sequence up to the tandem pair of Arg residues. Further truncation results in a dramatic loss of activity.28,29 Truncation improves purification because the full-length protein often is strongly associated with E. coli chaperone proteins, and the majority of the expressed protein is sequestered in inclusion bodies. The (+)-LS gene was modified to replace codons of the plastidial target sequence (amino acid residues 1–52, inclusive) with a His6 tag (used for purification) that was then followed by the tandem Arg pair, R53 and R54, and remaining coding sequence for the mature protein. (+)-LS was transformed into BL21-CodonPlus(DE3)-RIL cells (Agilent Technologies) that contain extra copies of the tRNAs that recognize the infrequently used codons for Arg, Leu, and Ile (often found in plant terpene synthase genes). The protein was purified using immobilized nickel affinity chromatography resulting in roughly 10–20 mg of soluble protein/L of cells and >90% purity as judged by SDS-PAGE (Figure S2A). FPLC SEC on Superdex-200 showed predominantly a single peak corresponding to a molecular weight of ~70 kDa that is consistent with the molecular weight expected for a monomer (562 amino acids; MW = 65.7 kDa) (Figure S2B).

Activity

Initially we tested both GPP (for synthesis, see Experimental Procedures) and farnesyl diphosphate (FPP) (Sigma) as possible substrates for (+)-LS. A discontinuous in vitro single-vial assay was used to monitor enzyme activity.16 In a 1 mL reaction mixture, the divalent cation (Mn2+ or Mg2+), substrate, and enzyme were combined and overlaid with an equal volume of hexanes. The reaction mixture was incubated overnight before the reaction was quenched with vigorous mixing for 30 s and extraction of hydrophobic compounds into the organic phase, which was then loaded directly onto the GC-MS instrument. Reaction products were identified on the basis of the measured fragmentation patterns generated by the mass spectrometer in comparison to commercially available terpene standards. Incubation with FPP resulted in no detectable product, even after several days (data not shown). In Figure 2A, the gas chromatogram for the reaction with GPP clearly shows the production of limonene as the major species (99% total product). Smaller amounts of the monoterpenes β-myrcene (0.7%) and α-pinene (0.3%) were also detected. Terpene synthases are known to be capable of producing multiple terpene products;30 however, (+)-LS appears to exhibit a high degree of control over product outcome and generates mainly a single product.

Figure 2.

Identification of (+)-limonene as the major product and determination of enantioselectivity of the (+)-LS reaction. (A) Gas chromatogram for the product of an overnight reaction of GPP and (+)-LS showing the production of limonene, with smaller amounts of other monoterpenes. (B) Molar CD spectra for the enzymatic product from the reaction shown in panel A (black), a (+)-limonene standard (red), and a (−)-limonene standard (blue). The color code is the same for panels A and B.

In a control experiment, no hexane extractable terpene products were produced in the absence of divalent metal ion. The enzyme generated the same distribution of terpene products in the presence of either magnesium or manganese; however, the maximal rate of turnover differed (Figure S3). The concentration at which the enzyme reached optimal activity was significantly lower for Mn2+ (600 μM) than for Mg2+ (20 mM), and Mg2+ at saturating levels was capable of producing limonene at only ~60% of the rate for optimal Mn2+. Additionally, enzyme activity increased gradually with increasing magnesium concentration until it reached a point of saturation (above 20 mM), whereas enzyme activity was acutely affected by even small increases in manganese concentration and was strongly inhibited at concentrations of >1 mM. This inhibitory effect has been observed for other terpene synthases, although the mechanism behind it remains undetermined.31 In mixed metal experiments, the inhibitory effects of millimolar Mn2+ were still observed even at saturating Mg2+ concentrations. Some terpene synthases have also been shown to be dependent on monovalent cations, specifically K+, for activity.32 However, when tested, no effect on the (+)-LS reaction rate was observed with either potassium or sodium at concentrations from 0 to 300 mM. Above 300 mM, activity sharply declined likely because of nonspecific effects of ionic strength.

Circular dichroism measurements were taken to determine the enantiomeric selectivity of (+)-LS. CD spectra for control samples of pure (+)- and (−)-limonene were compared with those of enzymatically produced limonene. Enantiopure samples of (+)- and (−)-limonene generated characteristic spectra with distinguishable Cotton effects. Spectra for the enzymatic product and (+)-limonene standard were nearly superimposable after correction for differences in concentration. The results of these experiments show not only that (+)-LS produces the (+)-enantiomer but also that the reaction is stereospecific in that it produces negligible if any of the (−)-enantiomer within the limits of detection using this method (Figure 2B). These results are in agreement with those published for the nearly identical (+)-LS from C. unshiu in which it was shown using separation on a chiral GC column that the enzyme made exclusively the (+)-enantiomer.26

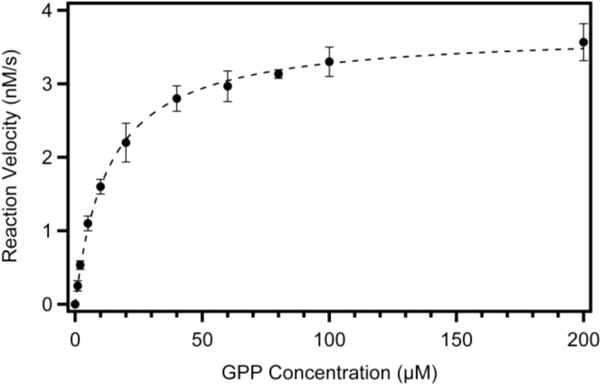

Enzymatic activity was also measured by following the production of limonene over time while varying the concentration of substrate. The enzyme exhibited classical Michaelis-Menten saturation kinetics where reaction rates plotted against substrate concentration were fit well by the equation v = (Vmax[S])/(KM + [S]). From these data (Figure 3), it was possible to extract a KM of 13.1 ± 0.6 μM and a kcat of 0.186 ± 0.002 s−1. Both numbers fall within the typical range observed for other terpene synthases in the literature. No substrate inhibition was observed in the range of GPP concentrations tested, unlike what had been previously reported for the (+)-LS from lemon.15 The same experiment was conducted substituting magnesium for manganese, and consistent with the metal ion dependency data, the catalytic turnover appeared to be reduced by ~40%; the KM was also shifted by ~3-fold (kcat = 0.118 ± 0.005 s−1, and KM = 35 ± 6 μM).

Figure 3.

Michaelis-Menten plot for reaction of GPP with (+)-LS. This figure shows a plot of reaction velocity (nanomolar limonene produced per second; ordinate) vs GPP concentration (micromolar; abscissa). Each reaction mixture contained 20 nM (+)-LS, the indicated concentration of GPP substrate (1–200 μM), and 400 μM MnCl2. Reactions were performed as described in Experimental Procedures. The reaction for each concentration of GPP was performed in triplicate, where error bars represent the standard error of the mean. The data were fit to a rectangular hyperbola by nonlinear regression analysis with a KM of 13.1 ± 0.6 μM and a kcat of 0.186 ± 0.002 s−1.

Structure of Apo-(+)-LS

Apo-(+)-LS crystallized from PEG-8000 solutions in space group P41212 with one molecule in the asymmetric unit. The structure was determined by molecular replacement using (−)-LS from M. spicata as a search model (PDB entry 2ONG) and refined to 2.3 Å resolution. Electron density was weak for residues of the N-terminus up to and including Q59, the T219-E225 loop, the Q574-E577 loop, and residues of the C-terminus following L592, and for this reason, these residues were not included in the final structure. As shown in Figure 4, the protein is composed of two domains typical of plant monoterpene synthases: an N-terminal domain of unknown function and a C-terminal domain responsible for catalytic activity. The catalytic domain displays the classic “terpene synthase fold” composed of 12 helices.33,34 Six (C, D, F, G1–G2, H2-H-α1, and J) of the 12 helices form the walls of the active site cavity that is lined with mostly nonpolar, hydrophobic, and aromatic amino acid residues35 and is flanked on either side by the metal ion binding residues D343, D347, and D488 that are part of conserved motifs [DDXXD] and [(N/D)DXX(S/T)XXXE].4 In contrast to the other apo structures of monoterpene synthases, bornyl diphosphate synthase35 and 1,8-cineole synthase,36 (+)-LS displays clear electron density for the H-α1 helix. The H-α1 helix is believed to be involved in closing the active site to solvent upon binding of substrate.

Figure 4.

Cylindrical helix model of apo-(+)-LS. The N-terminal domain is colored green and the C-terminal domain blue. Residues of the conserved metal ion binding sites are colored red.

We observe unaccounted-for electron density deep in the active site that cannot be modeled with GPP substrate, limonene product, buffer molecules, or other compounds present in the crystallization solutions, and no metal ions are found bound to the protein. This density was not present when crystals were soaked with fluorinated substrates (DOI: 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b00144).

Comparison of Apo-(+)-LS with FLPP-Bound (−)-LS

Superposition of the structures of apo-(+)-LS, described here, and FLPP-bound-(−)-LS (PDB entry 2ONG)11 shows no significant differences in overall fold with an rmsd (Cα atoms) of 1.4 Å, despite the fact that the sequences of these two proteins are only 44.7% identical (Figure S4). However, there are a few differences in the catalytic C-terminal domain that likely can be ascribed to differences between an open active site conformation [our apo-(+)-LS structure] and a closed, ligand-bound conformation [the FLPP-bound (−)-LS structure]. Most notable is an ordering of the N-terminal strand and loop between the J and K helices, which together form a lid covering the active site in the (−)-LS structure while the short H-α1 helix shifts ~5 Å inward to cover the active site from below (Figure 5). The H-α1 helix is stabilized in the open conformation by a series of hydrogen bonds with residues on helix I (S494 Oγ⋯E517 Oε, T492 O⋯R521 NH2, and L490 O⋯R521 NH1) (Figure 6A) that are lost upon the transition to the closed conformation. T492 reorients to coordinate Mn2+C in the ligand-bound conformation; P503 acts as a hinge that allows movement of the H-α1 helix, and a hydrogen bond between the carbonyl oxygen of V502 and Nε2 of Q507 is broken, resulting in relocation of V502 and an ~180° rotamer flip of the Q507 side chain (Figure 6B). Two final changes of note in the closed conformation are reorientation of D347 to coordinate two of the Mn2+ ions (Figure 5) and movement of the phenolic side chain of Y565 in the J helix from a position outside of the active site to a position in the active site with the -OH group pointing toward the ligand (Figures 5).

Figure 5.

Superposition of the active site of apo-(+)-LS (blue) and FLPP-bound-(−)-LS (green; PDB entry 2ONG) structures.

Figure 6.

Tertiary interactions important for stabilizing the H-αl helix region in the open [(+)-LS] and closed [(−)-LS] (PDB entry 2ONG) conformations of the enzyme. (A) Hydrogen bonds between the H-α1 and I helices are shown as dotted lines in the open conformation of apo-(+)-LS. (B) The open conformation of apo-(+)-LS (blue) superposed with the closed conformation of FLPP-bound (−)-LS (green) reveals a hinge at P503.

The J helix is a half-turn longer, and the loop between the J and K helices is outwardly projected in the apo structure (Figures 5). Upon substrate binding, the loop between the J and K helices moves to cover the active site and partially unwinds the J helix by a half-turn up to Y565. This unwinding event appears to trigger the side chain of Y565 to flip inward toward the active site. The hydroxyl group of the Y565 side chain [Y573 in (−)-LS] comes within hydrogen bonding distance (2.8 Å) of Oδ1 in the bidentate carboxylate side chain of the manganese-coordinating D488 [D496 in (−)-LS] and is 3 Å from C2 of the prenyl chain of FLPP in the (−)-LS structure. To investigate the role of Y565 in catalysis, the residue was mutated to Phe (Y565F), preserving the aromaticity and hydrophobicity of the side chain while removing its hydrogen bonding capability. The Y565F mutant was expressed at levels similar to that of the wild-type protein but was found to have a reduced activity with a kcat of 0.004 s−1 and a modestly smaller KM of 4.6 μM for GPP (see Figure S5). These data suggest that the phenolic side chain may indeed move into the active site upon substrate binding and that this transition is important for the full activity of the enzyme. Additionally, while the major product formed by the reaction of the Y565F mutant of (+)-LS with GPP was still limonene, oxygenated monoterpenes (mainly isomers of terpineol) were also produced in smaller proportions as was the isomerized hydrolysis product of GPP, linalool (Figure S6). The wild-type enzyme does not generate any oxygenated products. The transition to the closed active site conformation is likely critical to excluding solvent molecules from the active site that might react with high-energy carbenium ion intermediates along the reaction coordinate.

DISCUSSION

Citrus Fruit History and Sequence Differences

Citrus fruit evolutionary history has been difficult to assess comprehensively.37 Oranges in particular have become heavily cross-bred, which makes it difficult to trace the origins of any one species. Most of the differences between subspecies of oranges are phenotypic (i.e., thicker rind and sweeter juice) and these qualitative traits are likely to be differently interpreted worldwide, resulting in many names for many different cultivars, which further convolutes the tracing of their agricultural history.37 Branch grafting onto host citrus trees also means that some trees may be producing multiple different species of fruit at the same time.

Our gene for (+)-LS came from a navel orange purchased from a local supermarket. Navel oranges are a popular subvariety of sweet oranges (C. sinensis) noted for their thick skin, lack of seeds, and signature navel, which is the result of a second immature fruit forming at the base of the orange. Sequence alignment with other reported (+)-limonene synthases identified the gene product CitMTSE2 from satsuma mandarin orange (C. unshiu) as the closest homologue (99.7% identical). These two orange subspecies are vastly different in morphology, yet the limonene synthase gene has not seen robust changes in sequence. As navel oranges were first recognized only 200 years ago, it is possible that the two orange subtypes have not had enough time for their genomes to diverge significantly.38 In a recent genome sequencing effort for C. sinensis (cv. Valencia), it has been proposed that the sweet orange as we know it today is the result of a more ancient hybrid backcross between a pommelo and a mandarin, suggesting that the satsuma mandarin and the navel orange might be more closely related than their difference in appearance implies.39

Enantiomeric Selectivity

A surprising result of this structural investigation has been that two terpene synthases somehow evolved ways of selecting for the production of one enantiomer of the same terpene skeleton over another even though they share similar global protein folds. Although (−)- and (+)-LS produce two different enantiomeric compounds, there appear to be very few differences in amino acid residues present in the active site that may confer this selectivity (Figure 7). Enantiomeric selectivity in these enzymes is thought to be conferred by the initial binding configuration of the substrate.2,6 Support for this hypothesis is provided by a crystal structure for (+)-LS bound to the fluorinated substrate analogue 2-fluoro GPP, presented in the following article in this issue (DOI: 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b00144).

Open to Closed Structural Differences

Despite sharing only 44.7% sequence identity, the structures of apo-(+)-LS and FLPP-bound (−)-LS show few significant differences in the overall fold of the proteins (Cα atom rmsd of 1.4 Å). Differences between the structures near the active site can thus be considered to be representative of the conformational changes associated with substrate binding. This is especially true for the N-terminal strand, J–K loop, and H-α1 helix. What might the structural differences observed between our apo structure and the analogue-bound structure of (−)-LS from M. spicata mean for the mechanism of monoterpene cyclization? As we follow the structures from open to closed, we observe the inward motion of the H-α1 helix, similar to what is observed in other terpene synthases.35,36 It is believed that this short helix acts to close off the active site from solvent molecules, protecting the highly reactive carbocations from premature quenching by water. It appears that the movement of this helix is triggered by the breaking and making of only a few hydrogen bonds driven by the coordination of Mn2+C by T492. The inward movement of the H-α1 helix is likely to be coupled to the capping of the active site by the N-terminal strand, stabilized at one end by the tandem pair of Arg and at the other end by an invariant Trp residue (W63) that forms hydrophobic packing interactions above the active site.

The Tyr at position 565 on the J helix appears to undergo a transition from a position outside of the active site in the apo- (+)-LS structure to a position close to the substrate and metal binding site in the (−)-LS structure. This residue could be important for stabilizing reaction intermediates, preventing water from entering the active site, or providing additional stability to metal coordination through a hydrogen bond with D488. Protein sequence alignment and structural investigation for a broad subset of terpene synthases across all types (monoterpene, sesquiterpene, diterpene, plant, fungal, and bacterial) show that this residue is nearly 100% conserved (data not shown). Such invariance suggests that the residue would be required for catalytic activity, and indeed, mutation of this Tyr to Phe did decrease activity 50-fold. Clearly, the coordinated closure of the active site upon substrate and metal binding, and the involvement of Y565 in that transition, must be studied in greater detail.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the staff at the Advanced Light SourceBerkeley Center for Structural Biology for their assistance during X-ray data collection. The Advanced Light Source is funded by the Director, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, of the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract DE-AC02-05CH11231. The Berkeley Center for Structural Biology is supported in part by grants from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant T32GM007596 (B.R.M. and J.O.M.).

ABBREVIATIONS

- GPP

geranyl diphosphate

- FPP

farnesyl diphosphate

- GGPP

geranylgeranyl diphosphate

- LPP

linalyl diphosphate

- CD

circular dichroism

- GC–MS

gas chromatography–mass spectrometry

- rmsd

root-mean-square deviation

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b00143.

Protein sequence alignment (Figure S1), Purification of (+)-LS as followed by SDS–PAGE and SEC (Figure S2), Divalent metal cation dependence of activity (Figure S3), Apo-(+)-LS and (−)-LS comparative overlay (Figure S4), Michaelis-Menten plot for reaction of GPP with (+)-LSY565F (Figure S5), and Gas chromatogram for reaction of the Y565F mutant with GPP (Figure S6) (PDF)

Accession Codes

The nucleotide sequence for full-length (+)-LS from C. sinensis (navel orange) has been deposited as GenBank accession code KU746814. The atomic coordinates and structure factors for apo-(+)-LS have been deposited as PDB entry 5UV0.

ORCID

Benjamin R. Morehouse: 0000-0003-3352-5463

Daniel D. Oprian: 0000-0002-6520-5459

Author Contributions

B.R.M. and R.P.K. contributed equally to this work.

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.Pichersky E, Gershenzon J. The formation and function of plant volatiles: perfumes for pollinator attraction and defense. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2002;5:237–243. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(02)00251-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cane DE. Isoprenoid biosynthesis – stereochemistry of the cyclization of allylic pyrophosphates. Acc Chem Res. 1985;18:220–226. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cane DE. Enzymatic formation of sesquiterpenes. Chem Rev. 1990;90:1089–1103. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christianson DW. Structural biology and chemistry of the terpenoid cyclases. Chem Rev. 2006;106:3412–3442. doi: 10.1021/cr050286w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christianson DW. Unearthing the roots of the terpenome. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2008;12:141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis EM, Croteau R. Cyclization enzymes in the biosynthesis of monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes, and diterpenes. Top Curr Chem. 2000;209:53–95. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao Y, Honzatko RB, Peters RJ. Terpenoid synthase structures: a so far incomplete view of complex catalysis. Nat Prod Rep. 2012;29:1153–1175. doi: 10.1039/c2np20059g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aaron JA, Christianson DW. Trinuclear metal clusters in catalysis by terpenoid synthases. Pure Appl Chem. 2010;82:1585–1597. doi: 10.1351/PAC-CON-09-09-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lesburg CA, Caruthers JM, Paschall CM, Christianson DW. Managing and manipulating carbocations in biology: terpenoid cyclase structure and mechanism. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1998;8:695–703. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(98)80088-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwab W, Williams DC, Davis EM, Croteau R. Mechanism of monoterpene cyclization: stereochemical aspects of the transformation of noncyclizable substrate analogs by recombinant (−)-limonene synthase, (+)-bornyl diphosphate synthase, and (−)-pinene synthase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2001;392:123–136. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hyatt DC, Youn B, Zhao Y, Santhamma B, Coates RM, Croteau RB, Kang C. Structure of limonene synthase, a simple model for terpenoid cyclase catalysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:5360–5365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700915104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodriguez A, San Andres V, Cervera M, Redondo A, Alquezar B, Shimada T, Gadea J, Rodrigo MJ, Zacarias L, Palou L, Lopez MM, Castanera P, Pena L. Terpene down-regulation in orange reveals the role of fruit aromas in mediating interactions with insect herbivores and pathogens. Plant Physiol. 2011;156:793–802. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.176545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chuck CJ, Donnelly J. The compatibility of potential bioderived fuels with Jet A-1 aviation kerosene. Appi Energy. 2014;118:83–91. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keller RK, Thompson R. Rapid synthesis of isoprenoid diphosphates and their isolation in one step using either thin layer or flash chromatography. Journal of Chromatography A. 1993;645:161–167. doi: 10.1016/0021-9673(93)80630-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lucker J, El Tamer MK, Schwab W, Verstappen FWA, van der Plas LHW, Bouwmeester HJ, Verhoeven HA. Monoterpene biosynthesis in lemon (Citrus limon) – cDNA isolation and functional analysis of four monoterpene synthases. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:3160–3171. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.02985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Maille PE, Chappell J, Noel JP. A single-vial analytical and quantitative gas chromatography-mass spectrometry assay for terpene synthases. Anal Biochem. 2004;335:210–217. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Battye TGG, Kontogiannis L, Johnson O, Powell HR, Leslie AGW. iMOSFLM: a new graphical interface for diffraction-image processing with MOSFLM. Acta Crystallogr, Sect D: Biol Crystallogr. 2011;67:271–281. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910048675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evans P. Scaling and assessment of data quality. Acta Crystallogr, Sect D: Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62:72–82. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905036693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Winn MD, Ballard CC, Cowtan KD, Dodson EJ, Emsley P, Evans PR, Keegan RM, Krissinel EB, Leslie AGW, McCoy A, McNicholas SJ, Murshudov GN, Pannu NS, Potterton EA, Powell HR, Read RJ, Vagin A, Wilson KS. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr, Sect D: Biol Crystallogr. 2011;67:235–242. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910045749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Potterton E, Briggs P, Turkenburg M, Dodson E. A graphical user interface to the CCP4 program suite. Acta Crystallogr, Sect D: Biol Crystallogr. 2003;59:1131–1137. doi: 10.1107/s0907444903008126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Afonine PV, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Moriarty NW, Mustyakimov M, Terwilliger TC, Urzhumtsev A, Zwart PH, Adams PD. Towards automated crystallographic structure refinement with phenix.refine. Acta Crystallogr, Sect D: Biol Crystallogr. 2012;68:352–367. doi: 10.1107/S0907444912001308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, Zwart PH. PHENIX: A comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr, Sect D: Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott W, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr, Sect D: Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wise ML, Savage TJ, Katahira E, Croteau R. Monoterpene synthases from common sage (Salvia officinalis). cDNA isolation, characterization, and functional expression of (+)-sabinene synthase, 1,8-cineole synthase, and (+)-bornyl diphosphate synthase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:14891–14899. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.24.14891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shimada T, Endo T, Fujii H, Omura M. Isolation and characterization of a new d-limonene synthase gene with a different expression pattern in Citrus unshiu Marc. Sci Hortic. 2005;105:507–512. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Colby SM, Alonso WR, Katahira EJ, Mcgarvey DJ, Croteau R. 4S-limonene synthase from the oil glands of spearmint (Mentha-spicata) – cDNA isolation, characterization, and bacterial expression of the catalytically active monoterpene cyclase. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:23016–23024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams DC, McGarvey DJ, Katahira EJ, Croteau R. Truncation of limonene synthase preprotein provides a fully active ’pseudomature’ form of this monoterpene cyclase and reveals the function of the amino-terminal arginine pair. Biochemistry. 1998;37:12213–12220. doi: 10.1021/bi980854k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williams DC, Wildung MR, Jin AQW, Dalal D, Oliver JS, Coates RM, Croteau R. Heterologous expression and characterization of a “pseudomature” form of taxadiene synthase involved in paclitaxel (Taxol) biosynthesis and evaluation of a potential intermediate and inhibitors of the multistep diterpene cyclization reaction. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;379:137–146. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steele CL, Crock J, Bohlmann J, Croteau R. Sesquiterpene synthases from grand fir (Abies grandis) – Comparison of constitutive and wound-induced activities, and cDNA isolation, characterization and bacterial expression of delta-selinene synthase and gamma-humulene synthase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:2078–2089. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.4.2078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rajaonarivony JIM, Gershenzon J, Croteau R. Characterization and mechanism of (4S)-limonene synthase, a monoterpene cyclase from the glandular trichomes of peppermint (Mentha x piperita) Arch Biochem Biophys. 1992;296:49–57. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90543-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Green S, Squire CJ, Nieuwenhuizen NJ, Baker EN, Laing W. Defining the potassium binding region in an apple terpene synthase. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:8661–8669. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807140200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lesburg CA, Zhai GZ, Cane DE, Christianson DW. Crystal structure of pentalenene synthase: Mechanistic insights on terpenoid cyclization reactions in biology. Science. 1997;277:1820–1824. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5333.1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wendt KU, Schulz GE. Isoprenoid biosynthesis: manifold chemistry catalyzed by similar enzymes. Structure. 1998;6:127–133. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(98)00015-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Whittington DA, Wise ML, Urbansky M, Coates RM, Croteau RB, Christianson DW. Bornyl diphosphate synthase: structure and strategy for carbocation manipulation by a terpenoid cyclase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:15375–15380. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232591099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kampranis SC, Ioannidis D, Purvis A, Mahrez W, Ninga E, Katerelos NA, Anssour S, Dunwell JM, Degenhardt J, Makris AM, Goodenough PW, Johnson CB. Rational conversion of substrate and product specificity in a Salvia monoterpene synthase: Structural insights into the evolution of terpene synthase function. Plant Cell. 2007;19:1994–2005. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.047779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu GA, Prochnik S, Jenkins J, Salse J, Hellsten U, Murat F, Perrier X, Ruiz M, Scalabrin S, Terol J, Takita MA, Labadie K, Poulain J, Couloux A, Jabbari K, Cattonaro F, Del Fabbro C, Pinosio S, Zuccolo A, Chapman J, Grimwood J, Tadeo FR, Estornell LH, Munoz-Sanz JV, Ibanez V, Herrero-Ortega A, Aleza P, Perez-Perez J, Ramon D, Brunel D, Luro F, Chen CX, Farmerie WG, Desany B, Kodira C, Mohiuddin M, Harkins T, Fredrikson K, Burns P, Lomsadze A, Borodovsky M, Reforgiato G, Freitas-Astua J, Quetier F, Navarro L, Roose M, Wincker P, Schmutz J, Morgante M, Machado MA, Talon M, Jaillon O, Ollitrault P, Gmitter F, Rokhsar D. Sequencing of diverse mandarin, pummelo and orange genomes reveals complex history of admixture during citrus domestication. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:656–62. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.The Citrus Industry. 1st. Vol. 1. University of California; Berkeley, CA: 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu Q, Chen LL, Ruan X, Chen D, Zhu A, Chen C, Bertrand D, Jiao WB, Hao BH, Lyon MP, Chen J, Gao S, Xing F, Lan H, Chang JW, Ge X, Lei Y, Hu Q, Miao Y, Wang L, Xiao S, Biswas MK, Zeng W, Guo F, Cao H, Yang X, Xu XW, Cheng YJ, Xu J, Liu JH, Luo OJ, Tang Z, Guo WW, Kuang H, Zhang HY, Roose ML, Nagarajan N, Deng XX, Ruan Y. The draft genome of sweet orange (Citrus sinensis) Nat Genet. 2013;45:59–66. doi: 10.1038/ng.2472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.