Abstract

The development of nanotheranostic agents that integrate diagnosis and therapy for effective personalized precision medicine has obtained tremendous attention in the past few decades. In this report, biocompatible electron donor–acceptor conjugated semiconducting polymer nanoparticles (PPor-PEG NPs) with light-harvesting unit is prepared and developed for highly effective photoacoustic imaging guided photothermal therapy. To the best of our knowledge, it is the first time that the concept of light-harvesting unit is exploited for enhancing the photoacoustic signal and photothermal energy conversion in polymer-based theranostic agent. Combined with additional merits including donor–acceptor pair to favor electron transfer and fluorescence quenching effect after NP formation, the photothermal conversion efficiency of the PPor-PEG NPs is determined to be 62.3%, which is the highest value among reported polymer NPs. Moreover, the as-prepared PPor-PEG NP not only exhibits a remarkable cell-killing ability but also achieves 100% tumor elimination, demonstrating its excellent photothermal therapeutic efficacy. Finally, the as-prepared water-dispersible PPor-PEG NPs show good biocompatibility and biosafety, making them a promising candidate for future clinical applications in cancer theranostics.

1. Introduction

The development of nanoscaled theranostic agents that integrate diagnosis and therapy for effective personalized precision medicine has obtained tremendous attention in the past several decades.[1–4] By virtue of their real-time diagnostic capability, theranostic platforms can identify the location of tumor, detect the accumulation of theranostic agents, and monitor the therapeutic response as well as destroy tumors with higher specificity and sensitivity.[5–7] Among different diagnostic modalities, photoacoustic imaging (PAI) allows imaging beyond the optical diffusion limit because it detects phonons instead of photons upon photoexcitation, providing higher spatial resolution and deeper tissue penetration over traditional optical imaging techniques (e.g., fluorescence imaging).[8–10] On the other hand, most PAI contrast agents naturally consist in therapeutic agents for photothermal therapy (PTT) because PAI takes advantage of the ultrasound detection for the photothermally converted acoustic waves.[11–15] Thus, synergistically combining PAI and PTT into one theranostic system has emerged as a powerful tool in cancer treatment owing to its noninvasiveness, deep penetration, high selectivity, and high effectiveness without systemic side effects.[11–15]

Up to now, the most widely developed PAI/PTT agents are inorganic nanomaterials such as noble metal nanomaterials (e.g., Au and Pd),[16–18] transition metal dichalcogenides (e.g., MoS2, WS2 nanosheets, and CuS2 nanoparticles),[19–21] and carbon nanomaterials (e.g., graphene and carbon nanotubes).[5,22,23] However, a potential concern is that these typical nonbiodegradable inorganic nanomaterials could remain in the body for a long period of time, which could lead to potential long-term biotoxicity and significantly hinder their further clinical translations.[12,24–27] More recently, small-molecule organic dyes have been explored as PAI/PTT agents owing to their good biocompatibility and potential biodegradability.[28–30] On the other hand, it has also been reported that anticancer efficacy of small-molecules-based PTT agents can be limited by their poor thermal stability and low photothermal conversion efficiencies, as part of the absorbed energy is converted to fluorescence.[8,31,32] Therefore, new biocompatible PAI/PTT agents with high photothermal conversion efficiency and good photostability are highly desired.

In this regard, semiconducting polymer nanoparticles (SPNs) prepared from hydrophobic semiconducting polymer building blocks have emerged as a new class of PAI or PTT agents due to their high absorption coefficients, good biocompatibilities, and good photostabilities.[8,33–38] Pu and co-workers reported that SPNs can be developed into efficient PAI probes for in vivo imaging of reactive oxygen species and pH, respectively.[36,39,40] They further demonstrated that the photoacoustic (PA) brightness of SPNs is correspondingly dependent on their photothermal conversion efficiency by studying the structure–property relationship of several diketopyrrolopyrrole-based SPNs and thus extended their applications to PTT.[35] However, there are relatively few works on the design and preparation of SPNs for enhancing PA brightness or improving PTT efficiency based on the structure/component–property relationship.[35,37] Very recently, Pu and co-workers introduced two optically active components in one SPN, within which the primary semiconducting polymer and the optical dopant, respectively, acted as electron donor and acceptor.[35,36] These two components could be easily paired and aligned to favor photoinduced electron transfer, which resulted in fluorescence quenching, enhancing nonradiative heat generation, and ultimately amplifying both PA brightness or PTT efficiency.[35,36]

Based on this, herein we designed and fabricated SPN for highly effective PAI-guided PTT based on electron donor–acceptor (D–A) conjugated semiconducting polymer molecules which show a low band gap to ensure a high red light-absorbing ability. To further enhance the photothermal conversion efficiency, we introduce, for the first time, a light-harvesting unit side branch to the D–A polymer chain. The resulting SPN indeed demonstrates a record-high photothermal conversion efficiency of 62.3% and complete in vivo tumor elimination.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Preparation and Characterization of Biocompatible Electron Donor–Acceptor Conjugated Semiconducting Polymer Nanoparticles (PPor-PEG NPs)

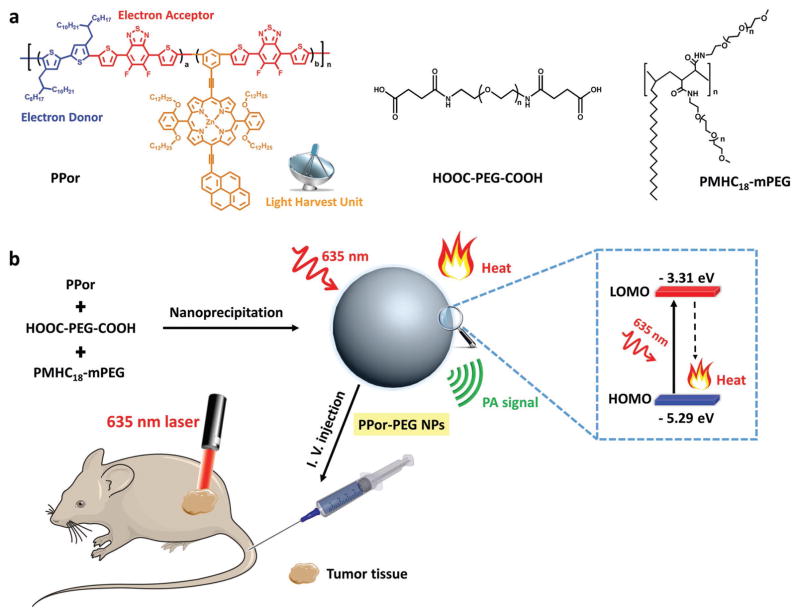

The D–A conjugated semiconducting polymer PPor was synthesized via microwave-assisted Stille-coupling copolymerization from 5,6-difluoro-4,7-bis[5-(trimethylstannyl) thiophen-2-yl]-benzo-2,1,3-thiadiazole (as an electron acceptor), 5,5′-dibromo-4,4′-bis(2-octyldodecyl)-2,2′-bithiophene (as an electron donor) and porphyrin–pyrene pendant (Figure 1a), as reported in our previous work.[41] Such a D–A based molecular architecture is conducive to introducing intramolecular charge transfer to redshift and enhance the Q-band absorption, resulting in broadened absorption and increased extinction coefficient which can be beneficial to PTT.[42–44] It was shown that the porphyrin–pyrene pendant acts as a light-harvesting unit to greatly enhance the photoinduced charge generation in polymeric solar cell.[41] In our previous work,[41] we have presented the absorption spectrum of the light-harvesting unit, which demonstrated that the porphyrin–pyrene unit exhibits typical porphyrin absorption over the B bands (near maximum peak of 481 nm) and the Q bands (near maximum peak of 673 nm). The photo-physical processes of the as-prepared PPor upon light absorption is shown in Figure S1 (Supporting Information). The PPor molecule absorbs photons and becomes activated from its ground state (S0) to a higher excited singlet state. The molecule subsequently relaxes through internal conversion or vibrational relaxation to the lowest excited state (S1). The excited molecules at the lowest excited state may (1) decay back to the ground state by emitting fluorescence from its S1, (2) undergo intersystem crossing to triplet state (T1), or (3) relax to the ground state via a nonradiative vibrational relaxation. All involved vibrational relaxations are mediated by collisions between the PPor molecule and its surrounding environment in a process that leads to heat generation by transferring energy from the PPor molecule to surrounding molecules. Herein, the light-harvesting unit could enhance the light-absorbing ability and improve the photoheat conversion efficiency for PTT/PAI.[45] To the best of our knowledge, such a concept of light-harvesting unit side chain has never been exploited for biomedical applications.

Figure 1.

Design and preparation of PPor-PEG NPs for PAI-guided PTT. a) Chemical structures of PPor, HOOC-PEG-COOH, and PMHC18-mPEG used for the fabrication of PPor-PEG NPs. b) Illustration of preparation of PPor-PEG NPs via nanoprecipitation and mechanism of PPor-PEG NP-based PTT.

The highest occupied molecular orbital and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital are −5.29 and −3.31 eV for PPor, respectively. Its narrow band gap is beneficial for red light-absorbing capability and photothermal efficiency (Figure 1b). To improve the bioavailability of the hydrophobic PPor molecule, PPor-PEG NPs were prepared via a well-documented nanoprecipitation approach, where two hydrophilic polymers, HOOC-PEG-COOH and PMHC18-mPEG, were mixed to increase water-dispersibility and size-stability. PPor NPs without adding PEG were also fabricated with the same method for comparison. As shown in Figure 2a, the PPor-PEG NPs can be well dispersed in deionized (DI) water while the PPor NPs without PEG can only attach to the inside surface of the glass bottle due to its poor water dispersibility. Eventually, the as-obtained water-dispersible PPor-PEG NPs were intravenously injected into tumor-bearing mice for PAI-guided PTT (Figure 1).

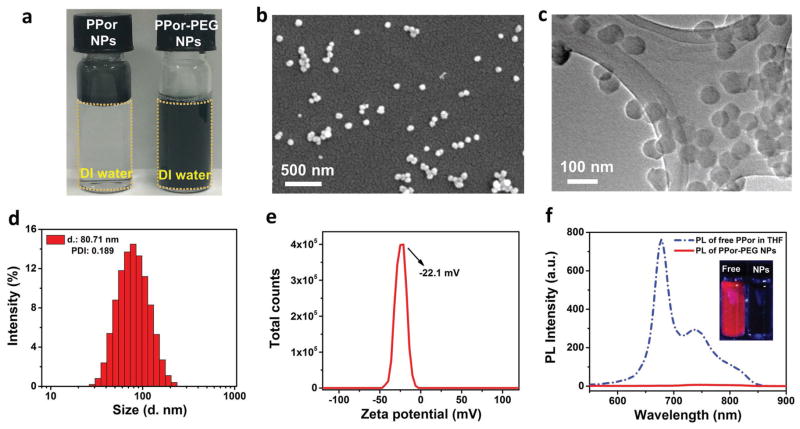

Figure 2.

Characterization of the PPor-PEG NPs. a) Photographs of the solutions of PPor NPs and PPor-PEG NPs dispersed in DI water. b) SEM and c) TEM images of the as-prepared PPor-PEG NPs. d) Dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurement and e) zeta potential of the PPor-PEG NPs in DI water. f) Fluorescence spectra of free PPor molecules dissolved in THF and PPor-PEG NPs dispersed in DI water respectively. Inset shows photographs of the two samples under UV light.

Figure 2b,c is scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of the PPor-PEG NPs, revealing their well-defined spherical morphology of 70–80 nm in diameter. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurement gives a hydrodynamic diameter of ≈81 nm and a polydispersity index of 0.189 (Figure 2d), which is consistent with the results from SEM and TEM. Furthermore, due to the existence of several thiophene groups on the PPor molecule, the as-prepared PPor-PEG NPs appeared to be negatively charged with a zeta potential of around −22.1 mV (Figure 2e). This negative charge can not only stabilize the NPs by electrostatic repulsion but also reduce the serum protein adsorption to enhance their accumulation at the tumor site.[46] Owing to the electrostatic repulsion and the PEGylation, the resulting PPor-PEG NPs exhibit good dispersibility in different physiological solutions including fetal bovine serum (FBS), cell culture medium (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium, DMEM), and phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (Figure S2, Supporting Information). They also show good stability in these solutions after storage at room temperature for 7 d, with no aggregation or agglomeration. SEM and TEM images of the PPor-PEG NPs after 21 d of storage further demonstrate that the size of these NPs remains unchanged (Figure S3, Supporting Information). We also demonstrated the good size stability of the as-prepared NPs in both PBS and various pH buffers ranging from 3 to 9 obtained by mixing buffer solutions of citric acid and Na2HPO4 in different ratios (Figure S4, Supporting Information). All these results suggest that the PPor-PEG NPs possess good water dispersibility and robust size stability, which are beneficial for their future biomedical applications.

We also measured fluorescence spectra of the free PPor molecules dissolved in tetrahydrofuran (THF) and the PPor-PEG NPs dispersed in DI water, respectively. As shown in Figure 2f, insets are the photographs of the two samples under UV light; PPor molecules in THF display an obvious red florescence. By contrast, PPor in the form of NPs exhibits negligible fluorescence due to aggregation-induced quenching. To demonstrate that the fluorescence quenching effect is due to aggregation of the molecules rather than PEG addition, we measured the fluorescence spectrum of the pure PPor NP without PEG (Figure S5, Supporting Information), which also show significant fluorescence quenching compared with the free PPor molecules in THF. Very recently, Pu and co-workers has pointed out that the PA brightness and photothermal conversion efficiency would be enhanced when the fluorescence brightness decreased.[37] They found that both the PA intensity and solution temperature of poly[2,6-(4,4-bis(2-ethylhexyl)-4H-cyclopenta-[2,1-b;3,4-b′]dithiophene)-alt-4,7-(2,1,3-benzothiadiazole)] (PCPDTBT) polymer NPs increased obviously with the increase in the doping amount of (6,6)-phenyl-C71-butyric acid methyl ester (PC70BM), which would gradually quench the fluorescence intensity of PCPDTBT.[37] This complies well with the photophysical mechanisms where fluorescence emission competes with the thermal deactivation through vibrational relaxation in determining acoustic and heat generation upon photoexcitation.[47] Therefore, in this work, the fluorescence quenching effect of the as-prepared PPor-PEG NPs would be in favor of improving their PAI and PTT efficiencies.

2.2. Photochemical and Photothermal Properties of the PPor-PEG NPs

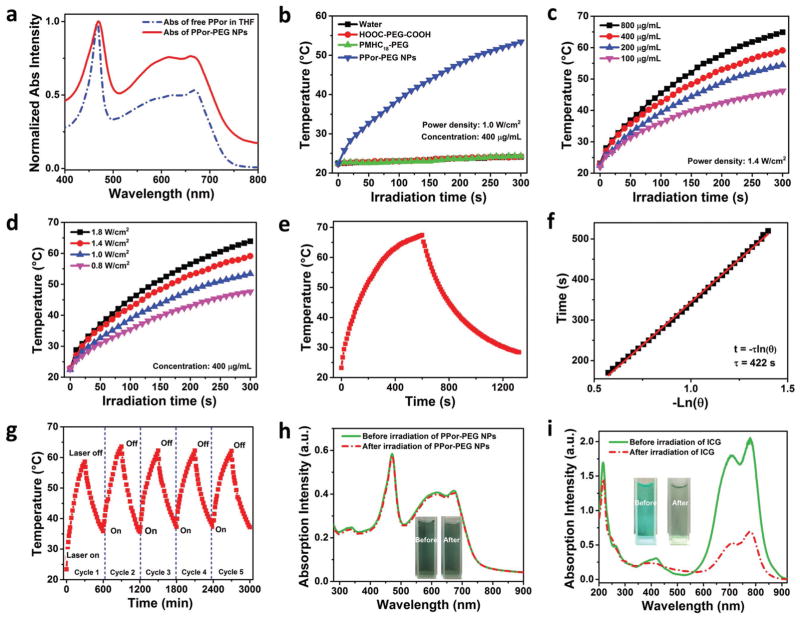

Figure 3a shows the UV–vis absorption spectra of the free PPor molecules and the PPor-PEG NPs with broad absorption over the range of 400–750 nm. Their absorption in the red to near-infrared region from 600 to 750 nm is important for PAI/PTT applications. To show the photothermal effects, photothermal heating curves of water dispersions of the PPor-PEG NPs, HOOC-PEG-COOH, and PMHC18-mPEG as well as water were respectively measured under 1 W cm−2 635 nm laser irradiation for 300 s (Figure 3b). Only PPor-PEG NPs exhibit a prominent temperature increase reaching almost 55 °C within only 5 min, while the temperature variations for the other groups under the same dose of irradiation are negligible, indicating that the remarkable heat generation originates from the PPor polymer rather than PEGs. Concentration and laser-power-density-dependent temperature elevation from the PPor-PEG NPs were studied (Figure 3c,d) to facilitate their PAI/PTT applications.

Figure 3.

Photochemical and photothermal properties of the PPor-PEG NPs. a) Absorption spectra of free PPor molecules dissolved in THF and PPor-PEG NPs dispersed in DI water. b) Photothermal heating curves of water, HOOC-PEG-COOH, PMHC18-mPEG, and PPor-PEG NP dispersions upon 635 nm laser irradiation. Photothermal heating curves of the PPor-PEG NPs c) with different concentrations upon 1.4 W cm−2 635 nm laser irradiation and d) with different laser power densities at 400 μg mL−1. e) Photothermal effect of the PPor-PEG NPs dispersions under irradiation of a 635 nm laser (1.4 W cm−2), which was turned off after irradiation for 600 s. f) Plot of cooling time versus negative natural logarithm of the temperature driving force obtained from the cooling stage as shown in (e). g) Temperature variations of the PPor-PEG NPs under irradiation at a power density of 1.4 W cm−2 for five light on/off cycles (5 min of irradiation for each cycle). Absorption spectra of h) the PPor-PEG NPs and i) indocyanine green (ICG) solutions before and after 635 nm laser irradiation at a power density of 1.4 W cm−2 for 5 min; insets are photographs of the PPor-PEG NPs and the ICG solutions before (left) and after (right) laser irradiation.

In short, the present system has the following merits: (1) donor–acceptor pair to favor electron transfer resulting in fluorescence quenching and enhancing nonradiative heat generation; (2) narrow band gap and light-harvesting unit to ensure good red light absorbing; and (3) fluorescence quenching effect upon NP formation to enhance the photothermal performance of the as-prepared PPor-PEG NPs. To measure their photothermal conversion efficiency, we first monitored the temperature change of the PPor-PEG NP dispersion under continuous irradiation with a 635 nm laser (1.4 W cm−2), which was turned off when the temperature reached a steady-state after irradiation for 600 s (Figure 3e). Figure 3f displays the plot of cooling time versus negative natural logarithm of the temperature driving force obtained from the cooling stage; as shown in Figure 3e, the time constant for heat transfer of the system was determined to be τs = 422 s. Based on the reported method[48] and obtained data shown in Figure 3e, photothermal conversion efficiency of the PPor-PEG NPs was determined to be 62.3% (more details on the Experimental Section). To the best of our knowledge, this value is the highest photothermal conversion efficiency among reported polymer NPs including polypyrrole NPs (45%),[49] dopamine-melanin NPs (40%),[50] heterocyclic conductive polymer PPDS NPs (31.4%),[51] and poly(cyclopentadithiophene-alt-diketopyrrolopyrrole) SPNs (20%).[38] Moreover, the photothermal conversion efficiency of the as-prepared PPor-PEG NPs is much higher than that of commercial Au nanoshells (13%) and Au nanorods (21%),[48] Cu2−xSe (22%) nanocrystals,[48] Cu2−xS nanocrystals (16.3%),[52] and MoS2 nanosheets (24.4%).[53]

Interestingly, even after five cycles of heating and cooling, the PPor-PEG NPs still raised the temperature to the same level, suggesting that as-prepared NPs have excellent photo-stability, which can afford repeated PTT treatment (Figure 3g). The photothermal stability was further confirmed by comparing with that of indocyanine green (ICG). We chose ICG for comparison because it is a typical U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved commercial dye used as an intravenously administered contrast agent for PA imaging in the clinic,[54] which shows strong absorption over 600–700 nm. ICG has also been used in the clinic for PA imaging. As depicted in Figure 3h,i, there is negligible degradation in UV–vis absorption of the PPor-PEG NPs, while the absorption of ICG is greatly diminished after 635 nm laser irradiation for 5 min. The insets also show no observable color change in the PPor-PEG NPs dispersion but obvious fading from light green to colorless in the ICG solution. Furthermore, we also investigated photo-stability of the as-prepared PPor-PEG NPs in different environments such as PBS (pH 7.4) and solutions with different pHs (ranging from 3 to 9). As displayed in Figure S6 (Supporting Information), no absorption degradation was observed in both PBS and other buffer solutions with different pH values when compared with that in deionized water, demonstrating that the PPor-PEG NPs exhibit good photostability in different physiological solutions. The high photothermal efficiency and good photothermal stability of the as-prepared PPor-PEG NPs make them a promising and highly effective PAI/PTT agent.

2.3. Photoacoustic Properties of the PPor-PEG NPs

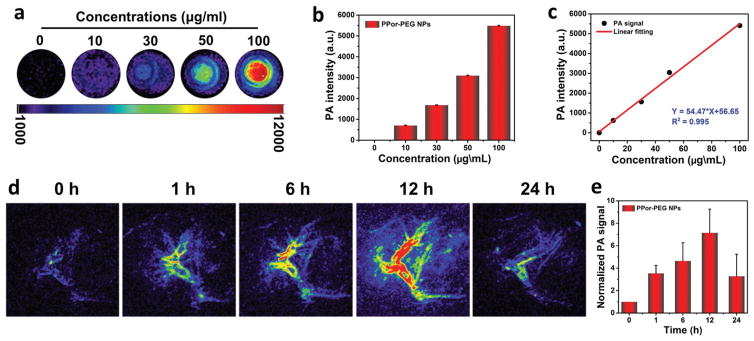

After confirming the excellent photothermal performances, we next investigated the PA properties of the as-fabricated PPor-PEG NPs. Figure 4a,b shows the PA images and the corresponding PA signal intensities of the PPor-PEG NPs at different concentrations from 10 to 100 μg mL−1 upon excitation at 680 nm. It is worth pointing out that even at a low concentration of 100 μg mL−1, the PA signal intensity of the PPor-PEG NPs can increase dramatically compared to the control group without NPs, showing its outstanding PA property. Furthermore, it is obvious to observe a linear correlation between the PA signals and the corresponding NP concentrations (Figure 4c), which is beneficial to their future quantitative PA imaging.

Figure 4.

PA properties of the PPor-PEG NPs. a) PA images and b) corresponding PA signal intensity of PPor-PEG NP dispersions of different concentrations (680 nm laser). c) The linear relationship between PA signal and concentration of PPor-PEG NPs. d) In vivo PA imaging of tumor tissue before and after tail injection of PPor-PEG NPs under 680 nm laser irradiation at different time points (0, 1, 6, 12, and 24 h). e) Normalized PA signals in tumor at different times.

Apart from evaluating the PA properties of the PPor-PEG NPs in vitro, we also investigated their PA performance in the tumor site. As exhibited in Figure 4d,e, in vivo PA images and the corresponding normalized PA signals of tumor tissue before and after tail injection of the PPor-PEG NPs under 680 nm laser irradiation were recorded at different times. The clear and strong PA signals of the tumors shown in these images suggest that the PPor-PEG NPs can be efficiently accumulated at the tumor site owing to the enhanced permeability and retention effect. At 12 h postinjection, the PA signal intensity reached a maximum value, which illustrates that 12 h after injection was determined to be the optimal time for PTT of tumor. In addition, the PA signal in tumor site after 24 h postinjection was still three times higher than that of pre-injection of the NPs, indicating that the PPor-PEG NPs can serve as a long-term PA contrast agent in vivo.

2.4. In Vitro Cytotoxicity of the PPor-PEG NPs as a PTT Agent

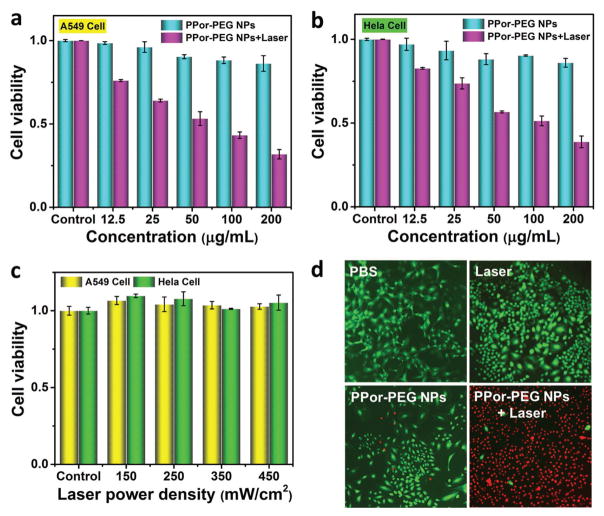

To evaluate in vitro cytotoxicity of the PPor-PEG NPs as a PTT agent, we measured the relative cell viabilities using A549 human lung cancer cells and HeLa human cervical cancer cells through 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assays. As depicted in Figure 5a,b, the PPor-PEG NPs with 635 nm laser irradiation show a dose-dependent cytotoxicity against both A549 and HeLa cells. Meanwhile, without laser irradiation, even at 200 μg mL−1 of the PPor-PEG NPs, the cell viabilities remain near 90% for both cell lines, demonstrating a good biocompatibility of the as-prepared NPs. Because the NPs exhibit a superior cell-killing ability to A549 cell line, we would use this type of cell line to inoculate mice for the following in vivo PTT experiments. Furthermore, Figure 5c shows the effect of 635 nm laser irradiation on A549 and HeLa cells without the NPs. The results confirm that the laser irradiation itself has negligible cytotoxicity and the cell deaths shown in Figure 5a,b are indeed due to the combined effects of the NPs under irradiation.

Figure 5.

In vitro cytotoxicity against a) A549 cells and b) HeLa cells of PPor-PEG NPs with or without 635 nm laser irradiation at a power density of 350 mW cm−2 for 5 min. c) In vitro cytotoxicity against A549 cells and HeLa cells under 635 nm laser irradiation at different power densities. d) Fluorescence images of calcein AM (green, live cells) and propidium iodide (red, dead cells) costained A549 cells with PBS, only laser irradiation, only PPor-PEG NPs, and PPor-PEG NPs with laser irradiation.

To further prove the highly effective cytotoxicity of the PPor-PEG NPs as a PTT agent, viability of the A549 cells was monitored by costaining with calcein acetoxymethylester (Calcine AM) and propidium iodide (PI) to differentiate live (green) and dead (red) cells. As illustrated in Figure 5d, compared with the control group (PBS only), the cells exhibit negligible cytotoxicity when only irradiated with laser or only incubated with the PPor-PEG NPs, while the cells incubated with the PPor-PEG NPs upon laser irradiation were mostly killed. These results are consistent with the above MTT results and suggest that the as-prepared PPor-PEG NPs have a remarkable cell-killing ability, making it a promising platform for highly effective PTT in vivo.

2.5. In Vivo Antitumor Activity and Biosafety of the PPor-PEG NPs

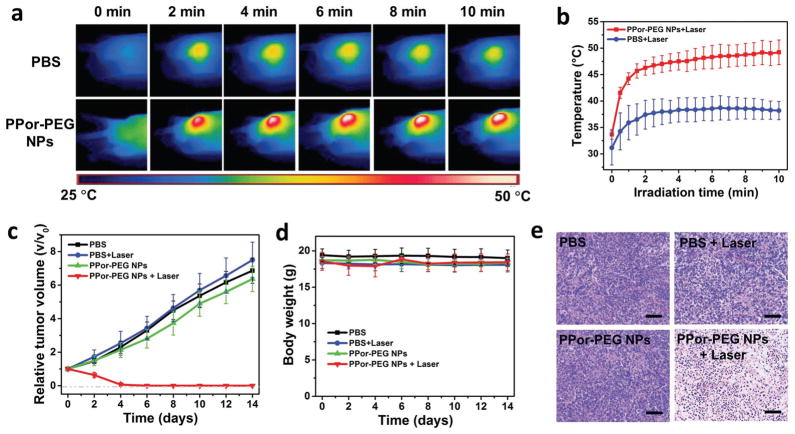

Encouraged by the remarkable in vitro cell-killing ability via PTT, we then carried out animal experiments to demonstrate the in vivo antitumor activities of the PPor-PEG NPs. First, as illustrated in Figure 6a, infrared images of the A549 tumor-bearing mice intravenously injected with PBS and the PPor-PEG NPs exposed to 630 nm laser at power densities of 1 W cm−2 after different irradiation times were respectively taken. The corresponding temperatures of the tumors at these time intervals are shown in Figure 6b. As expected, the temperature of tumors injected with the PPor-PEG NPs after laser irradiation rapidly increased and achieved a plateau at ≈ 50 °C within 10 min, while that of tumors injected with only PBS under the same condition showed only a mild temperature increase.

Figure 6.

a) Infrared thermal images of A549 tumor-bearing mice injected with PBS and PPor-PEG NPs exposed to 630 nm laser at a power density of 0.8 W cm−2 recorded at different time intervals, respectively. b) Temperature of tumors monitored by the infrared thermal camera in different groups upon laser irradiation as indicated in (a). c) Relative tumor volumes and d) body weight of mice treated with PBS, PBS + Laser, only PPor-PEG NPs, and PPor-PEG NPs + Laser. e) H&E staining images of tumor slices collected from mice after various treatments indicated above; scale bar is 100 μm.

After confirming the favorable in vivo photothermal effect of the as-prepared NPs at tumor sites, PTT tumor treatments were then carried out in four groups of mice (five mice for each group). Two groups of mice received tail injections of PBS, and the other two groups were injected with the PPor-PEG NPs. Tumor sites of one group of each of the injection formulation were further treated with a 635 nm laser (i.e., the four groups are: PBS only, PBS + Laser, NP only, and NP + Laser). As shown in Figure 6c,d, relative tumor volumes and body weight of mice treated with these various formulations were respectively recorded every other day in 14 d treatment. It can be clearly seen that only PPor-PEG NPs with laser treatment shows prominent tumor suppression and achieves complete tumor reduction, while the mice in the other three groups exhibit no or negligible tumor growth inhibition. Furthermore, the hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained images of tumor slices from A549 tumor-bearing mice after various treatments were also collected (Figure 6e). The nuclei presented in the PPor-PEG NPs + Laser treated tumor became condensed and the color of staining became shallower, suggesting obvious cell apoptosis or necrosis comparing to the other three groups. These images further demonstrated the remarkable therapeutic effect of the PPor-PEG NPs with laser irradiation.

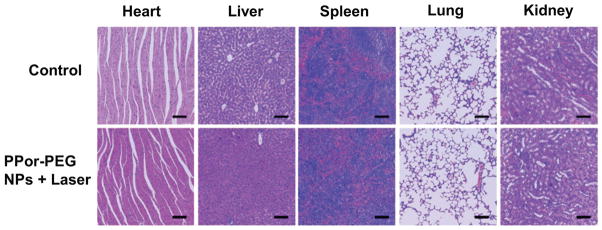

Finally, we evaluated the biosafety of the PPor-PEG NPs which is critical for their further clinical translation. On the one hand, the body weights of mice in each group were monitored accordingly. As presented in Figure 6d, no obvious body weight loss was found in all these groups, indicating no obvious side effect from the NPs or laser irradiation. On the other hand, we also collected the H&E-stained images of major organs including heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney histologic sections from mice treated with different formulations (Figure 7, Supporting Information). Compared to the control group, there is no observed inflammation lesion or organ damage in the PPor-PEG NPs with laser treated groups, evidencing good biosafety of the as-prepared PPor-PEG NPs. These preliminary results suggest that the PPor-PEG NP can serve as a potential clinically translatable nanomaterial for highly effective PAI guided PTT.

3. Conclusion

In conclusion, we developed PPor-PEG NPs with a light-harvesting unit for highly effective photoacoustic imaging guided photothermal therapy. To the best of our knowledge, it is the first time that a light-harvesting unit side group is exploited in polymer for enhancing photothermal conversion for biomedical applications. Integrated with the additional merits including donor–acceptor pair to favor electron transfer and fluorescence quenching effect after NP formation both resulted in enhancing nonradiative heat generation. The as-prepared PPor-PEG NP formula possesses an excellent photothermal performance with a photothermal conversion efficiency as high as 62.3%, which is the highest value reported in polymer NPs. The PA signal in tumor site at 24 h postinjection was still strong, indicating that PPor-PEG NPs can serve as a long-term PA contrast agent in vivo. Moreover, the as-prepared PPor-PEG NPs not only exhibited a remarkable cell-killing ability but also achieved complete tumor regression, suggesting the excellent PTT efficacy. Finally, the PPor-PEG NPs showed good biosafety, making them a promising candidate for future clinical application in photoacoustic diagnosis and photothermal therapy of cancer. We believe that the development of such water-dispersible semiconducting polymer nanoparticles will open new perspectives for exploring novel PAI/PTT agents for biomedical applications.

4. Experimental Section

Materials

PPor and PMHC18-mPEG were synthesized according to the previous work.[41,55] HOOC-PEG-COOH and MTT were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. DMEM, Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline (PBS, 10×, pH 7.4), antibiotic agents penicillin–streptomycin (10 000 U mL−1), FBS, and trypsin-EDTA (no phenol red, 0.5% trypsin) were purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific. Unless otherwise noted, all chemicals were used as received.

Preparation of the PPor-PEG NPs

The PPor-PEG NPs were prepared via a well-documented nanoprecipitation approach, where two hydrophilic polymers HOOC-PEG-COOH and PMHC18-mPEG were mixed to afford water-dispersibility and size-stability. In a typical run, 5 mg mL−1 PPor and PEG (weight percentage of PPor is 50%) in THF were prepared. PPor-PEG solution (200 μL) was quickly dispersed into milli-Q water (5 mL) under vigorous stirring at room temperature for 10 min. Next, the as-fabricated NPs suspension was sonicated for another 20 min. PPor NPs without adding PEG were also prepared with the same procedure for comparison. Afterwards, the as-prepared samples were freeze-dried and stored at 4 °C for future use.

Characterization of PPor-PEG NPs

Size and morphology of the PPor-PEG NPs were investigated on a Philips XL-30 FEG SEM and Philips CM200 FEG TEM. The SEM samples were prepared by dropping a dispersion of the PPor-PEG NPs onto a silicon substrate. The TEM samples were prepared by dropping the PPor-PEG NPs dispersion onto a carbon film followed by natural drying. Zeta potential and DLS measurements were carried out using a Malvern Zetasizer instrument. Absorption and fluorescence spectra were, respectively, measured by using a Cary 50Conc UV–Visible Spectrophotometer and a Cary Eclipse Fluorescence Spectrophotometer.

Photothermal Performance of the PPor-PEG NPs

The PPor-PEG NPs dispersions (400 μg mL−1, 2 mL), HOOC-PEG-COOH solution (400 μg mL−1, 2 mL), and PMHC18-mPEG solution (400 μg mL−1, 2 mL) were respectively measured upon 635 nm laser irradiation (1 W cm−2) for 300 s. DI water was used as a control. The PPor-PEG NPs dispersions with different concentrations (100, 200, 400, 800 μg mL−1) were irradiated with 635 nm laser at a power density of 1.4 W cm−2 for 300 s and the PPor-PEG NPs dispersions (400 μg mL−1, 2 mL) were also irradiated with 635 nm laser at different power densities (0.8, 1.0, 1.4, 1.8 W cm−2) for 300 s. During these measurements, a thermocouple probe was inserted into the aqueous solution of these samples in a position perpendicular to the laser path. Temperature was acquired every 10 s.

Photothermal conversion efficiency of the PPor-PEG NPs was calculated by recording the change in the temperature of the NPs aqueous dispersion as a function of time under continuous irradiation of 635 nm laser (1.4 W cm−2) for 600 s (t) until the solution reached a steady-state temperature. The photothermal conversion efficiency (η) was calculated according to Equation (1)[44]

| (1) |

where h represents the heat transfer coefficient, A is the surface area of the container, TMax represents the maximum steady-state temperature (67.1 °C), TSurr is the ambient temperature of the environment (20.4 °C), QDis represents the heat dissipation from the light absorbed by the solvent and the quartz sample cell, I is the incident laser power (1.4 W cm−2), and A635 is the absorbance of the sample at 635 nm (0.908). The value of hA is derived from Equation (2)

| (2) |

where τs is the time constant for heat transfer of the system, which was determined to be τs = 422 from Figure 3e; mD and cD, are the mass (2.0 g) and heat capacity (4.2 J g−1), respectively, of the DI water used to disperse the NPs. Thus, the hA was determined to be 0.0199 W. QDis represents the heat dissipation from the light absorbed by the water and the quartz sample cell, so QDis was calculated according to Equation (3)

| (3) |

where TMax(water) is 26.3 °C and τs(water) is 359; thus, QDis was calculated to be 0.138 W. According to the obtained data and Equation (1), the photothermal conversion efficiency of the PPor-PEG NPs was determined to be 62.3%.

In Vivo Photoacoustic Imaging

PA imaging was performed by using an Endra Nexus 128 scanner (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). 1%–2% isoflurane mixed with pure oxygen was used to maintain anesthesia of the mice during the whole experiment. Body temperature of the mice was maintained at 37.5 °C by using a water heating system during the scans. 680 nm was selected as the working laser wavelength. PA images were obtained before the injection of the NPs used as a control group. Then, the PPor-PEG NPs were tail intravenously injected into the mice and the PA images were respectively acquired at 1, 6, 12, and 12 h postinjection.

In Vitro Cytotoxicity by MTT Assay

A549 and HeLa cells were respectively seeded on 96-well plates in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco) for overnight. The original medium was then totally removed from each well. DMEM (200 μL) containing given concentrations of the PPor-PEG NPs was added to the designated wells. After incubation in the dark at 37 °C for 12 h, the cells incubated with the PPor-PEG NPs were irradiated with or without 635 nm laser (350 mW cm−2) for 5 min. The final concentration of the PPor-PEG NPs on each plate ranged from 12.5 to 200 μg mL−1. In addition, plates of A549 cells and HeLa cells were irradiated under 635 nm laser at different power densities from 150 to 450 mW cm−2 for 5 min to demonstrate the laser irradiation itself having no cytotoxicity. All these plates were then incubated at 37 °C in the dark for another 24 h. Subsequently, we removed the old medium and added DMEM (200 μL without FBS) containing 10% MTT stock solution (5 mg mL−1 in sterile PBS) to each well. After incubation for 4 h, the medium was removed completely, followed by adding dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, 200 μL) to each well. In vitro cell viabilities were measured by using a BioTek Powerwave XS microplate reader (read the absorbance at 540 nm). The cells incubated with DMEM without any treatment represented 100% cell survival.

Calcine AM/PI Test

The A549 cells were cultured in four 35 mm dishes with the same cell density. After overnight, the cells were respectively treated with PBS, only laser, only incubation with the PPor-PEG NPs, and incubation with the PPor-PEG NPs with laser irradiation (laser applied: 635 nm, 1 W cm−2, 5 min). Then, the cells were further incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. After staining with a mixture of Calcine AM/PI for 20 min and washing with PBS twice, images of the four samples were captured by using a fluorescence microscope.

In Vivo Antitumor Activity and Biosafety

The animal experiments have been approved by the Animal Management and Ethics Committee of Xiamen University. The Animal Management and Ethics Committee monitor and regulate animal experiments in accordance with relevant state regulations. T-cell-deficient male nude (nu/nu) mice, 5–6 weeks of age, were purchased from the Shanghai Slac Laboratory Animal Co. Ltd (Shanghai, China). 5 × 106 A549 cells were subcutaneously injected about two weeks before commencing treatment. When the tumors exhibited a volume of about 80 mm3, these mice were randomly divided into four groups with five mice in each cohort. The mice then received tail intravenous injections of different formulations including only PBS, PBS + Laser, only PPor-PEG NPs, and PPor-PEG NPs + Laser, respectively (laser irradiation applied: 630 nm, 0.8 W cm−2 for 10 min; concentration of various formulations: 1 mg mL−1, 300 μL). The final injected dose was 15 mg kg−1 per mouse. Both tumor volumes and mouse body weights were monitored every other day during the treatment (14 d). After 14 d from drugs administration, the mice were sacrificed. Both tumor tissue and major organs were dissected for H&E staining.

Supplementary Material

Figure 7.

H&E staining images of major organ slices collected from mice post various treatments indicated. Scale bar is 100 μm.

Acknowledgments

C.-S.L. would like to acknowledge financial support by the Guangdong Innovative and Entrepreneurial Research Team Program (Nos. 2013C090 and KYPT20141013150545116), and the City University of Hong Kong (Grant No. 9610352). C.-S.H. would like to acknowledge financial support from Ministry of Science and Technology, R.O.C. (MOST 103-2221-E-009-210-MY3). G.L. was supported by the Major State Basic Research Development Program of China (973 Program) (Grant Nos. 2013CB733802 and 2014CB744503), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (Grant Nos. 81422023, 51273165, and U1505221), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant Nos. 20720160065 and 20720150141), and the Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University, China (NCET-13-0502).

Footnotes

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

Contributor Information

Jinfeng Zhang, Center of Super-Diamond and Advanced Films (COSDAF), Department of Physics and Materials Science, City University of Hong Kong, 83 Tat Chee Avenue, Kowloon, Hong Kong S. A. R. 999077, P. R. China.

Caixia Yang, State Key Laboratory of Molecular Vaccinology and Molecular, Diagnostics Center for Molecular Imaging and Translational Medicine, School of Public Health, Xiamen University, Xiamen 361005, P. R. China.

Rui Zhang, Center of Super-Diamond and Advanced Films (COSDAF), Department of Physics and Materials Science, City University of Hong Kong, 83 Tat Chee Avenue, Kowloon, Hong Kong S. A. R. 999077, P. R. China.

Rui Chen, Center of Super-Diamond and Advanced Films (COSDAF), Department of Physics and Materials Science, City University of Hong Kong, 83 Tat Chee Avenue, Kowloon, Hong Kong S. A. R. 999077, P. R. China.

Dr. Zhenyu Zhang, Center of Super-Diamond and Advanced Films (COSDAF), Department of Physics and Materials Science, City University of Hong Kong, 83 Tat Chee Avenue, Kowloon, Hong Kong S. A. R. 999077, P. R. China

Prof. Wenjun Zhang, Center of Super-Diamond and Advanced Films (COSDAF), Department of Physics and Materials Science, City University of Hong Kong, 83 Tat Chee Avenue, Kowloon, Hong Kong S. A. R. 999077, P. R. China

Shih-Hao Peng, Department of Applied Chemistry, National Chiao Tung University, 1001 Ta Hsueh Road, Hsinchu 30010, Taiwan.

Prof. Xiaoyuan Chen, Chen Laboratory of Molecular Imaging and Nanomedicine (LOMIN), National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB), National Institutes of Health (NIH), Bethesda, MD 20892, USA

Prof. Gang Liu, State Key Laboratory of Molecular Vaccinology and Molecular, Diagnostics Center for Molecular Imaging and Translational Medicine, School of Public Health, Xiamen University, Xiamen 361005, P. R. China

Prof. Chain-Shu Hsu, Department of Applied Chemistry, National Chiao Tung University, 1001 Ta Hsueh Road, Hsinchu 30010, Taiwan

Prof. Chun-Sing Lee, Center of Super-Diamond and Advanced Films (COSDAF), Department of Physics and Materials Science, City University of Hong Kong, 83 Tat Chee Avenue, Kowloon, Hong Kong S. A. R. 999077, P. R. China

References

- 1.Davis ME, Chen G, Shin DM. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2008;7:771. doi: 10.1038/nrd2614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheng Z, Zaki AA, Hui JZ, Muzykantov VR, Tsourkas A. Science. 2012;338:903. doi: 10.1126/science.1226338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li C. Nat Mater. 2014;13:110. doi: 10.1038/nmat3877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ai X, Ho CJH, Aw J, Attia ABE, Mu J, Wang Y, Wang X, Wang Y, Liu X, Chen H, Gao M, Chen X, Yeow EKL, Liu G, Olivo M, Xing B. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10432. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim JW, Galanzha EI, Shashkov EV, Moon HM, Zharov VP. Nat Nanotechnol. 2009;4:688. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li Z, Hu Y, Howard KA, Jiang T, Fan X, Miao Z, Sun Y, Besenbacher F, Yu M. ACS Nano. 2016;10:984. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b06259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu J, Wang P, Zhang X, Wang L, Wang D, Gu Z, Tang J, Guo M, Cao M, Zhou H, Liu Y, Chen C. ACS Nano. 2016;10:4587. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.6b00745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pu K, Shuhendler AJ, Jokerst JV, Mei J, Gambhir SS, Bao Z, Rao J. Nat Nanotechnol. 2014;9:233. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2013.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang Y, Jeon M, Rich LJ, Hong H, Geng J, Zhang Y, Shi S, Barnhart TE, Alexandridis P, Huizinga JD, Seshadri M, Cai W, Kim C, Lovell JF. Nat Nanotechnol. 2014;9:631. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2014.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jathoul AP, Laufer J, Ogunlade O, Treeby B, Cox B, Zhang E, Johnson P, Pizzey AR, Philip B, Marafioti T, Lythgoe MF, Pedley RB, Pule MA, Beard P. Nat Photonics. 2015;9:239. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ge J, Jia Q, Liu W, Guo L, Liu Q, Lan M, Zhang H, Meng X, Wang P. Adv Mater. 2015;27:4169. doi: 10.1002/adma.201500323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He X, Bao X, Cao H, Zhang Z, Yin Q, Gu W, Chen L, Yu H, Li Y. Adv Funct Mater. 2015;25:2831. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cai X, Jia X, Gao W, Zhang K, Ma M, Wang S, Zheng Y, Shi J, Chen H. Adv Funct Mater. 2015;25:2520. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee MY, Lee C, Jung HS, Jeon M, Kim KS, Yun SH, Kim C, Hahn SK. ACS Nano. 2016;10:822. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b05931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zeng J, Cheng M, Wang Y, Wen L, Chen L, Li Z, Wu Y, Gao M, Chai Z. Adv Healthcare Mater. 2016;5:772. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201500898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Song J, Wang F, Yang X, Ning B, Harp MG, Culp SH, Hu S, Huang P, Nie L, Chen J, Chen X. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:7005. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b13475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu Y, Yang M, Zhang J, Zhi X, Li C, Zhang C, Pan F, Wang K, Yang Y, Fuentea JM, Cui D. ACS Nano. 2016;10:2375. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b07172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen M, Tang S, Guo Z, Wang X, Mo S, Huang X, Liu G, Zheng N. Adv Mater. 2014;26:8210. doi: 10.1002/adma.201404013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu T, Shi S, Liang C, Shen S, Cheng L, Wang C, Song X, Goel S, Barnhart TE, Cai W, Liu Z. ACS Nano. 2015;9:950. doi: 10.1021/nn506757x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng L, Liu J, Gu X, Gong H, Shi X, Liu T, Wang C, Wang X, Liu G, Xing H, Bu W, Sun B, Liu Z. Adv Mater. 2014;26:1886. doi: 10.1002/adma.201304497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Z, Huang P, Jacobson O, Wang Z, Liu Y, Lin L, Lin J, Lu N, Zhang H, Tian R, Niu G, Liu G, Chen X. ACS Nano. 2016;10:3453. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b07521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen D, Wang C, Nie X, Li S, Li R, Guan M, Liu Z, Chen C, Wang C, Shu C, Wan L. Adv Funct Mater. 2014;24:6621. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang K, Hu L, Ma X, Ye S, Cheng L, Shi X, Li C, Li Y, Liu Z. Adv Mater. 2012;24:1868. doi: 10.1002/adma.201104964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khlebtsov N, Dykman L. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:1647. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00018c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharifi S, Behzadi S, Laurent S, Forrest ML, Stroeve P, Mahmoudi M. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:2323. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15188f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dong L, Li M, Zhang S, Li J, Shen G, Tu Y, Zhu J, Tao J. Small. 2015;11:2571. doi: 10.1002/smll.201403481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ou G, Li Z, Li D, Cheng L, Liu Z, Wu H. Nano Res. 2016;9:1236. [Google Scholar]

- 28.An FF, Deng Z, Ye J, Zhang J, Yang Y, Li C, Zheng C, Zhang X. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2014;6:17985. doi: 10.1021/am504816h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Y, Yang T, Ke H, Zhu A, Wang Y, Wang J, Shen J, Liu G, Chen C, Zhao Y, Chen H. Adv Mater. 2015;27:3874. doi: 10.1002/adma.201500229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sheng Z, Hu D, Zheng M, Zhao P, Liu H, Gao D, Gong P, Gao G, Zhang P, Ma Y, Cai L. ACS Nano. 2014;8:12310. doi: 10.1021/nn5062386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jin CS, Lovell JF, Chen J, Zheng G. ACS Nano. 2013;7:2541. doi: 10.1021/nn3058642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Geng J, Sun C, Liu J, Liao LD, Yuan Y, Thakor N, Wang J, Liu B. Small. 2015;11:1603. doi: 10.1002/smll.201402092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liang X, Li Y, Li X, Jing L, Deng Z, Yue X, Li C, Dai Z. Adv Funct Mater. 2015;25:1451. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hsiao CW, Chen HL, Liao ZX, Sureshbabu R, Hsiao HC, Lin SJ, Chang Y, Sung HW. Adv Funct Mater. 2015;25:721. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pu K, Mei J, Jokerst JV, Hong G, Antaris AL, Chattopadhyay N, Shuhendler AJ, Kurosawa T, Zhou Y, Gambhir SS, Bao Z, Rao J. Adv Mater. 2015;27:5184. doi: 10.1002/adma.201502285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miao Q, Lyu Y, Ding D, Pu K. Adv Mater. 2016;28:3662. doi: 10.1002/adma.201505681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lyu Y, Fang Y, Miao Q, Zhen X, Ding D, Pu K. ACS Nano. 2016;10:4472. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.6b00168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lyu Y, Xie C, Chechetka SA, Miyako E, Pu K. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:9049. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b05192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pu K, Shuhendler AJ, Rao J. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2013;52:10325. doi: 10.1002/anie.201303420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shuhendler AJ, Pu K, Cui L, Uetrecht JP, Rao J. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:373. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chao YH, Jheng JF, Wu JS, Wu KY, Peng HH, Tsai MC, Wang CL, Hsiao YN, Wang CL, Lin CY, Hsu CS. Adv Mater. 2014;26:5205. doi: 10.1002/adma.201401345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li D, Wang J, Ma Y, Qian H, Wang D, Wang L, Zhang G, Qiu L, Wang Y, Yang XZ. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8:19312. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b05495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang J, Chen W, Kalytchuk S, Li KF, Chen R, Adachi C, Chen Z, Rogach AL, Zhu G, Yu PKN, Zhang W, Cheah KW, Zhang X, Lee CS. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8:11355. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b03259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang J, Liu Z, Lian P, Qian J, Li X, Wang L, Fu W, Chen L, Wei X, Li C. Chem Sci. 2016;7:5995. doi: 10.1039/c6sc00221h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ng KK, Zheng G. Chem Rev. 2015;115:11012. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Feng T, Ai X, An G, Yang P, Zhao Y. ACS Nano. 2016;10:4410. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.6b00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Braslavsky SE, Heibel GE. Chem Rev. 1992;92:1381. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hessel CM, Pattani VP, Rasch M, Panthani MG, Koo B, Tunnell JW, Korgel BA. Nano Lett. 2011;11:2560. doi: 10.1021/nl201400z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen M, Fang X, Tang S, Zheng N. Chem Commun. 2012;48:8934. doi: 10.1039/c2cc34463g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu Y, Ai K, Liu J, Deng M, He Y, Lu L. Adv Mater. 2013;25:1353. doi: 10.1002/adma.201204683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim J, Lee E, Hong Y, Kim B, Ku M, Heo D, Choi J, Na J, You J, Haam S, Huh YM, Suh JS, Kim E, Yang J. Adv Funct Mater. 2015;25:2260. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang S, Riedinger A, Li H, Fu C, Liu H, Li L, Liu T, Tan L, Barthel MJ, Pugliese G, Donato FD, D’Abbusco MS, Meng X, Manna L, Meng H, Pellegrino T. ACS Nano. 2015;9:1788. doi: 10.1021/nn506687t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yin W, Yan L, Yu J, Tian G, Zhou L, Zheng X, Zhang X, Yong Y, Li J, Gu Z, Zhao Y. ACS Nano. 2014;8:6922. doi: 10.1021/nn501647j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nie L, Chen X. Chem Soc Rev. 2014;43:7132. doi: 10.1039/c4cs00086b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang J, Li S, An FF, Liu J, Jin S, Zhang JC, Wang PC, Zhang X, Lee CS, Liang XJ. Nanoscale. 2015;7:13503. doi: 10.1039/c5nr03259h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.