Abstract

Whether moving back home after a period of economic independence, or having never moved out, the share of emerging adults living with parents is increasing. Yet little is known about the associations of coresidence patterns and rationales for coresidence for emerging adult well-being. Using the Toledo Adolescent Relationships Study (n = 891), we analyzed depressive symptoms among emerging adults who (1) never left the parental home; (2) returned to the parental home; and (3) were not currently living with a parent. About one-fifth of emerging adults had boomeranged or moved back in with their parents. Among those living with parents, nearly two-fifths had boomeranged or returned to their parental home and they reported significantly higher levels of depressive symptoms. Among coresident emerging adults, both intrinsic and utilitarian motivations (i.e., enjoy living with parents and employment problems) partially mediated the association between coresidence and depressive symptoms. Returning to the parental home was associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms only among emerging adults experiencing employment problems. These findings are especially relevant because the recession hit emerging adults particularly hard. The ability to distinguish boomerang emerging adults and emerging adults who have never left home provides a more nuanced understanding of parental coresidence during this phase of the life course.

In contemporary American society, the transition to adulthood is complicated and far from uniform. Emerging adulthood is wrought with uncertainty as individuals navigate education, employment, and living arrangements, as well as relationships with parents and intimate partners (e.g., Arnett, 2004; Furstenberg et al., 2004). Further, emerging adults today have been hit hard by the recent economic recession resulting in additional complications and stress as individuals transition to adulthood. The current generation of young people—“Millenials”—have higher levels of student debt, and are more likely to experience poverty and unemployment compared with the two prior generations at comparable ages (Pew Research Center, 2014). Thus, many emerging adults are living with their parents—some of whom have never left whereas others are “boomeranging” or returning to their parents’ home. Despite frequent references to the “boomerang generation” or “boomerang kids” in previous work, few studies have empirically accounted for this group of emerging adults (see Ward & Spitze, 1996 for an exception).

Recent evidence indicates that about half (53%) of emerging adults ages 18–24 either currently live with parents or have moved back temporarily after a period of living independently (Pew Research Center, 2012). Most of the attention to emerging adults living with their parents is based on concerns about emerging adults who have boomeranged or returned home after they have left. Yet, many of those labeled “boomerangs” in prior work have never, in fact, moved out, resulting in incomplete assessments of the home-leaving process. To best understand patterns of home-leaving, it is important to differentiate those who have never left from those who moved back home—an assessment that is not permitted using most recent data.

Living independently is one of the key developmental tasks of emerging adulthood (Shanahan, 2000), and several studies have considered the well-being of emerging adults based on whether they coreside—or share a residence—with parents. Thus, comparisons drawn are most frequently based on coresident emerging adults (many of whom have never left their parental homes) and their independently-living peers. To date, no study has accounted for the varying coresidence histories (staying versus returning home) with regard to the link between living with parents and depressive symptoms. Further, prior studies have not considered whether emerging adults’ rationales associated with coresidence influenced variation or exacerbated the effects of two distinct types of coresidence—never leaving home, and returning home on depressive symptoms. The conditions under which coresidence has positive, negative, or no association with depressive symptoms is important in shedding light on whether a traditional criterion for adulthood, independent living, still matters for the transition to adulthood.

Using data from the Toledo Adolescent Relationships Study (TARS) (n = 891), we examined emerging adults’ living arrangements and self-reported well-being. We analyzed how never leaving the parental home, returning home after independent living, and independent living were associated with emerging adults’ depressive symptoms. We then examined emerging adults’ stated rationales for their living arrangements, and whether these specific considerations influenced the association between living arrangements and depressive symptoms. A unique feature of the TARS is that it allows for assessments of “boomeranging,” or the process of returning home. In addition, the prospective design of the TARS ensures our assessments of depressive symptoms accounted for prior depressive symptoms, which may affect selection into specific living arrangements. A further asset of the TARS is inclusion of measures on why emerging adults returned to or never left their parents’ home, as well as why they were motivated to coreside, including intrinsic and utilitarian considerations (i.e., socioemotional needs, not earning enough to support oneself, and unemployment). This research contributes to our understanding of emerging adult well-being and provides a more nuanced assessment of the implications of emerging adult-parental coresidence.

Background

Emerging Adulthood: Trends for Staying or Returning Home

Prior research has concluded that the majority of 18–25 year olds in the U.S. do not consider themselves to be adults (Arnett, 1997; Arnett, 2001; Arnett & Schwab, 2012), and researchers have begun to focus on the specific criteria emerging adults view as necessary to achieve adult status (e.g., Arnett, 1998; Buchmann, 1989; Nelson & Barry, 2005; Nelson et al., 2007; Shanahan, 2000). Although emerging adulthood is characterized by varied and indirect routes to adulthood (Arnett 2000; Furstenberg, 2010; Shanahan, 2000), at the top of the list of criteria for adulthood is self-reliance, including financial independence from parents (Arnett, 2001; Arnett & Schwab, 2012).

Yet in recent years, the prevalence of adult children living with parents has increased, and appears to contradict a traditional marker associated with self-reliance—independent living (Shanahan, 2000; Shanahan et al., 2005). In the U.S., marriage was the turning point signaling the establishment of independent living (Furstenberg, 2000). The average age of first marriage, however, in 2012, reached a highpoint of 28 for men and 26 for women (U.S. Census Bureau, 2012). Thus, it is perhaps not surprising that delays in marriage influenced delays in leaving the parental home.

Rather than marriage, emerging adults are increasingly leaving their parents’ home for other reasons including employment and educational opportunities, and to cohabit with intimate partners (Buck & Scott, 1993; Furstenberg, 2000; Goldscheider & Goldscheider, 1999). One difference between earlier and more recent generations is that in the past, emerging adults who moved out for reasons other than marriage were rarely welcomed back into the parents’ home (Goldscheider, Goldscheider, St. Clair, & Hodges, 1999). In contrast, many emerging adults currently rely on their parents’ home as a safety net because these increasingly common non-marital paths to independence are characterized by high levels of instability that may jeopardize independent living.

National data, for example, indicated that poor employment opportunities and the increasing cost of housing have contributed to a recent uptick in coresidence (Hallquist et al., 2011; Painter, 2010; U.S. Census Bureau, 2009; Wang & Morin, 2009). Thus, these structural changes in the broader economy and the housing market, in addition to delayed first marriage (Settersten, 1998; Settersten & Ray, 2010), have extended the average length of coresidence with parents and have increased the likelihood of returning home (Britton, 2013). This is in stark contrast to previous research findings indicating that employment (including losing, looking for, and finding a job) was not particularly relevant to the decision to reside with parents—both among those who never left as well as those who returned home (Ward & Spitze, 1996). Given the current economic climate and contemporaneous increase in coresidence, it seems especially important to further unravel the implications of coresidence, as well as rationales for staying/moving back home, among a contemporary cohort of emerging adults who are facing a distinct set of challenges related to their own financial futures and sense of economic security.

Given the barriers to making a “timely” transition to adulthood in the American context (i.e., rising educational requirements, limited job opportunities, student debt) coupled with limited governmental resources for young adults, the extension of the parental role is increasingly necessary (Hartnett, Furstenberg, Birditt, & Fingerman, 2013; Mortimer, 2012). Accordingly, researchers have begun to investigate if financial and residential (coresidence) supports provided by parents facilitate the transition to adulthood or if they result in increased and continued dependence (Swartz et al., 2011). Yet whether a parent’s home is a “home base” during periods of transition or a “safety net” in response to marital or economic failures (DaVanzo & Goldscheider, 1990), it is unclear how coresidence relates to emerging adult well-being. Some researchers have found that coresidence is not associated with increased dissatisfaction or conflict (e.g., Ward & Spitze, 1992). Rather, the experience of coresidence is generally positive for young adults (Cherlin, Scabini, & Rossi, 1997). This view, however, may underestimate the potential for variability in the effect of these living arrangements. Coresidence, after all, is not a universal option. Furthermore, conclusions regarding coresidence were drawn using data that did not distinguish those who have never left from those who have left and later returned to their parents’ home (e.g., Arnett & Schwab, 2013; Pew Research Center, 2013; Qian, 2010). Although these two groups share a common feature, currently residing with their parents, there is likely much diversity among them—particularly their reasons for coresiding.

Rationales for Residing with Parents and Emerging Adults’ Well-Being

Given that financial and residential independence are important milestones in the transition to adulthood (Shanahan, 2000; Shanahan et al., 2005), moves away from—and returns to—the parental home necessarily contain an element of discontinuity. As such, individuals may carry with them a heightened awareness of the reasons or justifications for this shift in their living arrangements. These reasons may condition the nature of the effect of the move itself on well-being. Returning to the parental home may be indicative of failure to reach important developmental markers associated with the transition to adulthood (i.e., financial independence). Even those who remain in their parents’ home are likely to have thought about these issues because as time goes by, they recognize that many of their peers have established independent residences. They may begin to ask, “Why am I still residing here?” To the extent that rationales for residing with parents provide a window to self-assessments of progress toward achieving adult status, answers to this question may influence well-being.

Following graduation from college or new employment, for example, periods of coresidence are common—sometimes even expected—experiences. Additionally, often the decision to move in with parents is much more sudden and made in response to a negative life event (Swartz et al., 2011). This might include such experiences as divorce, loss of employment, and unintended pregnancy. Although these life events may be the catalyst, they are not necessarily directly related to the move. It is in confronting these experiences, rather, that individuals make determinations as to how to proceed. These particular situations may not only be damaging to individuals’ self-conceptions, but may conflict with self-images as independent, self-sufficient adults. Individuals become especially cognizant of the stigma attached to moving home as they consider how society and their more immediate network respond to this living arrangement.

Yet studies that report a link between living arrangement and well-being often do not describe the mechanisms underlying that relationship (for exceptions see Kins, Beyers, Soenens, & Vansteenkiste, 2009; Kins & Beyers, 2010). Researchers have suggested that perhaps the motivation for the living arrangement is more important for well-being than the actual living arrangement. Kins and colleagues (2009), for example, found that the subjective well-being of young adults is more about autonomous motivations (i.e., wherein individuals actively choose to live with parents rather than being ‘forced’ based on economic necessity). We argue that rationales for coresiding with parents represent an important conceptual bridge between living arrangement and depressive symptoms. These lines of reasoning represent discrete decisions (from a snapshot in time) to either stay or return to the parents’ home; however, they map onto subjective understandings of criteria for adulthood and represent individual progress towards achieving adult status. Although these motivational processes are conceptualized in terms of a rather concrete residential decision, we argue that they involve much broader cognitive processes. That is, to the extent that rationales underlying coresidence are indicative of individual assessments of progress toward achieving criteria for adulthood, such considerations may contribute to depressive symptoms. Attention to the factors that result in residential decisions will provide us with a more thorough understanding of the association between emerging adult living arrangements and depressive symptoms.

Current Study

Extending prior work on parent-adult child coresidence, the current analyses examined the association between coresidence and depressive symptoms among emerging adults who (1) stayed in the parents’ home, (2) returned after a period of living independently, and (3) currently lived on their own. In assessing the role of living arrangement as a predictor, we overcame an important limitation of prior work by distinguishing between those who had never left and those who had returned to the parents’ home. Another contribution of our work is that by using longitudinal data we controlled for prior depressive symptoms. Previous studies have not accounted for earlier depressive symptoms.

A secondary objective was to focus on the subset of emerging adults who lived with their parents and determine whether rationales for departures from, and returns to, the parents’ home were systematically linked to variation in well-being. Analyses explored the degree to which intrinsic and extrinsic rationales mediated the relationship between living arrangement and emerging adults’ depressive symptoms, and whether such rationales conditioned the effect of living arrangement on well-being. Thus, our analyses not only documented the basic patterns, but focused on potential reasons for depressive symptoms.

Our analyses included a set of covariates that have been associated with emerging adult well-being and coresidence. These included parental closeness, gender, race, family background, socioeconomic status, relationship type, and parenthood status. Parental closeness was associated with young adults’ well-being (Whiteman, McHale, & Crouter, 2011). Both gender and race were linked to emotional well-being, including depressive symptoms, during young adulthood (McLeod & Owens, 2004). Furthermore, researchers have found racial and ethnic differences in patterns of home-leaving (e.g., Goldscheider & Goldscheider, 1999; Mitchell, Wister, & Gee, 2004) and women leave earlier and were less likely to return to their parental home (White, 1994). Family structure was also a salient predictor of early departures from the parental home (Aquilino, 1991). Numerous studies have identified associations between poverty and poor psychosocial functioning during the transition to adulthood (e.g., Duncan & Brooks-Gunn, 1997; Haveman, Wolfe, & Spaulding, 1991). Education and employment, historically, were important markers of adulthood, and emerging adults often actively pursue education (Settersten & Ray, 2010). Finally, relationship factors, including whether young adults were married or cohabiting, and presence of children influenced the residential decisions of young adults (Evenson & Simon, 2005).

Data and Methods

Data

The current study used data from the Toledo Adolescent Relationships Study (TARS), based on a stratified, random sample of adolescents who were registered for the 7th, 9th, and 11th grades in Lucas County, Ohio based on enrollment records from the year 2000. The initial sample (n=1, 321), devised by the National Opinion Research Center, was drawn from 62 schools across seven school districts with over-samples of Black and Hispanic students. Data were first collected from adolescents in 2001 using structured in-home interviews with preloaded questionnaires on laptop computers, and a parent or guardian was interviewed separately using pencil and paper questionnaires. Respondents were re-interviewed in 2002, 2004, and 2006. While the current study drew primarily on data from the fourth interview (2006), some of the sociodemographic characteristics, including parent education and family structure, were from the parent questionnaire administered at the time of the first interview (2001), and prior depressive symptoms were measured at the third interview (2004). The data from the fourth interview comprised 83% of the original sample.

The analytic sample consisted of all respondents for the fourth interview who were ages 18–24 (n = 1,068) with a few exclusions including 118 respondents who did not report either coresiding with parents or living independently (i.e., dorms, barracks, prison/jail, etc.), 17 reporting their race as “other,” and 42 who were still in high school at the time of the fourth interview for a final analytic sample of 891 respondents (481 females, 410 males).

Measures

Dependent variable

Depressive symptoms, measured using a six-item version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies’ depressive symptoms scale (CES-D) (Radloff, 1977), asked respondents how often each of the following statements was true during the past seven days: (1) “you felt you just couldn’t get going”; (2) “you felt that you could not shake off the blues”; (3) “you had trouble keeping your mind on what you were doing”; (4) “you felt lonely”; (5) “you felt sad”; and (6) “you had trouble getting to sleep or staying asleep.” Responses ranged from 1 (never) to 8 (every day) (alpha = .82). Prior depressive symptoms were measured using an identical scale from the third interview (alpha = .82). The third interview was conducted approximately 2 years prior to the fourth.

Independent variables

Parent residence dynamics

The focal independent variables were respondents’ living situations at the time of the fourth interview. Respondents were asked, “Where do you live now? That is, where do you stay most often?” Those who reported that they were living with their parents were subsequently asked, “Have you ever moved out on your own, meaning away from your mom and dad?” and “Have you ever moved back in with your parent(s)/guardian?” Those living with parents and reporting that they had never moved out on their own were categorized as stayed in the parental home. Respondents reporting that they (1) were living with their parents at the time of the interview, (2) had moved away from their parents at some point in the past, and (3) had moved back in with their parents were categorized as returned to the parental home. Finally, those who reported that they were not living with their parents at the time of the interview were categorized as living independently.

Rationales to reside with parents

Respondents were asked a series of questions reflecting intrinsic and utilitarian considerations regarding living arrangements—specifically their rationales for coresiding with parents. We focused on the following two rationales in the multivariate analyses: (1) “I enjoy living with my parent(s)”; and (3) “I lost my job or couldn’t find a job.” Each is a dichotomous variable (1 = yes). Other possible rationales included: “My parents needed my help”; “I needed my parents’ help”; “I counldn’t support myself”; and “I wanted to save money.” Respondents could cite any of these considerations; responses were not mutually exclusive.

Control variables

Parental closeness was a single interval-level item assessing the extent to which respondents felt close to their parents. Gender was a dichotomous variable with female as the contrast category. Age was respondents’ age in years at the time of the fourth interview. Three dichotomous indicators were used to measure respondents’ race/ethnicity including non-Hispanic White (contrast category), non-Hispanic Black, and Hispanic. Family structure during adolescence and parents’ reports of their highest level of education at the time of the first interview were used to measure parents’ resources. Family structure was composed of dichotomous variables indicating the household type in which respondents lived during adolescence including two biological parents (contrast category), stepfamily, single-parent family, and any “other” family type at the first interview. Because the parental sample consisted primarily of women, education is referred to as “mother’s education” and included the following categories: less than high school, high school (contrast category), some college, and college or more. Gainful activity was a dichotomous indicator defined as being currently enrolled in school or employed. Relationship status was a series of dichotomous variables indicating union type including married, cohabiting, dating, and single. Children was a continuous variable indicating the number of children the respondent had at the time of the fourth interview.

Analytic Strategy

We presented the descriptive statistics in Table 1. The multivariate analyses proceeded in two stages. In the first stage, presented in Table 2, we used ordinary least squares (OLS) regression to examine the relationship between parent residence dynamics and emerging adults’ depressive symptoms. Next, the models examined the extent to which parent residence dynamics affected emerging adults’ depressive symptoms net of parental closeness, gender, age, race, family structure during adolescence, mothers’ education, gainful activity, relationship status, parenthood, and prior depressive symptoms.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics, by Parent Residence Type (n = 891)a

| Full Sample | Stayed in the Parental Home (n = 302) | Returned to the Parental Home (n = 169) | Living Independently (n = 420) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Dependent Variable | Mean/Percentage | SD | Range | |||

| Depressive Symptoms | 14.46 | 30.00 | 6–48 | 13.72b | 16.16d | 14.30 |

|

| ||||||

| Independent Variables | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Parent Resident Type | ||||||

| Returned to the parental home | 19.49% | -- | -- | -- | ||

| Stayed in the parental home (Living independently) | 34.84% | -- | -- | -- | ||

| 45.67% | -- | -- | -- | |||

| Prior depressive symptoms | 14.76 | 28.81 | 6–48 | 14.04 | 15.42 | 15.11 |

| Rationales to Reside with Parentse | ||||||

| Enjoy living with parents | 65.48% | 76.65%b | 45.53% | -- | ||

| Employment problems | 13.85% | 10.85%b | 19.20% | |||

| Controls | ||||||

| Parental closeness | 4.14 | 3.07 | 1–5 | 4.24c | 4.13 | 4.07 |

| Female | 50.39% | 44.38%c | 48.95% | 55.59% | ||

| Age | 20.49 | 6.19 | 18–24 | 19.49bc | 20.77d | 21.14 |

| Race (White) | ||||||

| Black | 23.30% | 20.66% | 23.10% | 25.39% | ||

| Hispanic | 7.00% | 5.73% | 8.25% | 7.44% | ||

| Family structure (Two bio) | ||||||

| Single parent | 22.24% | 18.33%c | 23.91% | 24.51% | ||

| Step-parent | 13.16% | 10.00% | 12.42% | 15.89% | ||

| Other | 11.45% | 10.20% | 8.74% | 13.56% | ||

| Mother’s education (HS) | ||||||

| Less than HS | 9.79% | 7.25% | 11.35% | 11.07% | ||

| Some college | 35.26% | 35.00% | 31.56% | 37.03% | ||

| College or more | 23.09% | 22.93% | 22.86% | 23.31% | ||

| Gainfully active | 73.73% | 80.60%bc | 68.17% | 70.86% | ||

| Relationship Status (Single) | ||||||

| Dating | 40.43% | 50.51%c | 55.98%d | 26.10% | ||

| Cohabiting | 19.41% | 1.65%c | 6.69%d | 38.39% | ||

| Married | 6.33% | 0.36%c | 3.17%d | 12.24% | ||

| Children | 0.24 | 2.13 | 0–5 | 0.05c | 0.15d | 0.42 |

All means and standard deviations are weighted

Significant differences between stayed in the parental home and returned to the parental home

Significant differences between stayed in the parental home and living independently

Significant differences between returned to the parental home and living independently

Percentages for the motivations to reside with parents for the full sample are based on the subset living with parents (n = 471)

Table 2.

Coefficients for the OLS Regression of Depressive Symptoms on Parent Residence Type (n = 891)

| Bivariate | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| β | SE | β | SE | |

| Parent Residence Type | ||||

| Stayed in the parental home | −2.17** | 0.76 | −1.39* | 0.69 |

| Living independently (Returned to the parental home) | −1.68* | 0.72 | −1.32* | 0.67 |

| Prior depressive symptoms | 0.51*** | 0.03 | 0.47*** | 0.03 |

| Controls | ||||

| Parental closeness | −1.94*** | 0.32 | −1.07*** | 0.28 |

| Female | 1.29* | 0.53 | 1.00* | 0.47 |

| Age | 0.04 | 0.16 | 0.054 | 0.15 |

| Race (White) | ||||

| Black | 1.71** | 0.65 | 0.37 | 0.61 |

| Hispanic | 1.24 | 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.77 |

| Family structure (Two bio) | ||||

| Single parent | 0.99 | 0.67 | −0.66 | 0.61 |

| Step-parent | 2.57** | 0.81 | 0.95 | 0.71 |

| Other | 1.84* | 0.87 | −0.26 | 0.79 |

| Mother’s education (HS) | ||||

| Less than HS | 2.32* | 0.94 | 0.74 | 0.83 |

| Some college | 0.47 | 0.65 | 0.48 | 0.56 |

| College or more | −0.87 | 0.73 | −0.07 | 0.65 |

| Gainfully active | −3.65*** | 0.59 | −2.28*** | 0.56 |

| Relationship Status (Single) | ||||

| Dating | −1.62* | 0.63 | −1.87*** | 0.54 |

| Cohabiting | −1.82* | 0.75 | −2.91*** | 0.73 |

| Married | −1.20 | 1.10 | −2.26* | 1.04 |

| Children | 1.50*** | 0.45 | 0.41 | 0.46 |

| R2 | .31 | |||

p < .01;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

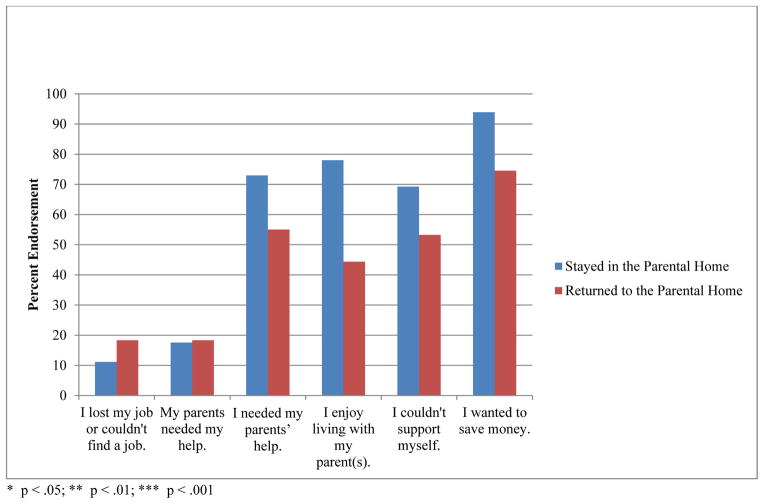

Second, we examined variation in rationales to reside with parents. These analyses were limited to respondents who never left the parental home (n = 302) or who returned after a period of independent living (n = 169). Figure 1 depicts the percent endorsement of the various rationales to coreside included in the TARS data. In Table 3, we presented the zero order relationships between living arrangement, rationales, and depressive symptoms. The subsequent regression models examined the association between living arrangement and depressive symptoms net of rationales, control variables and prior depression. We examined whether rationales mediated the relationship between parent residence dynamics and depressive symptoms. Finally, interactions were tested to determine whether the impact of parent residence dynamics on depressive symptoms was a function of rationales to reside with parents.

Figure 1.

Rationales to Coreside Among Young Adults Who Stayed and Returned Home

Table 3.

Coefficients for the OLS Regression of Depressive Symptoms on Parent Residence Type and Motivations to Reside with Parents: Main and Interaction Effects (n = 471)

| Bivariate | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | |

| Parent Residence Type | ||||||||

| Returned to the parental home (Stayed in the parental home) | 2.17** | 0.77 | 1.58* | 0.75 | 0.96 | 0.76 | 0.32 | 0.81 |

| Prior depressive symptoms | 0.53*** | 0.04 | 0.48*** | 0.04 | 0.46*** | 0.04 | 0.46*** | 0.04 |

| Rationales to Reside with Parents | ||||||||

| Enjoy living with parents | −4.36*** | 0.76 | −2.37** | 0.74 | −2.24** | 0.74 | ||

| Employment problems | 3.86*** | 1.08 | 1.25 | 0.97 | −0.66 | 1.30 | ||

| Controls | ||||||||

| Parental closeness | −2.27*** | 0.51 | −1.24** | 0.46 | −0.88† | 0.47 | −0.90† | 0.47 |

| Female | 0.66 | 0.75 | 1.21† | 0.66 | 1.32* | 0.65 | 1.43* | 0.65 |

| Age | 0.13 | 0.22 | −0.09 | 0.21 | −0.16 | 0.21 | −0.14 | 0.21 |

| Race (White) | ||||||||

| Black | 2.22* | 0.94 | 0.83 | 0.88 | 0.71 | 0.87 | 0.82 | 0.87 |

| Hispanic | 1.14 | 1.27 | 0.73 | 1.14 | 0.51 | 1.13 | 0.51 | 1.13 |

| Family structure (Two bio) | ||||||||

| Single parent | 1.68† | 0.96 | −0.40 | 0.88 | −0.53 | 0.87 | −0.43 | 0.87 |

| Step-parent | 2.93* | 1.21 | 0.83 | 1.08 | 0.86 | 1.07 | 0.91 | 1.07 |

| Other | 2.31† | 1.29 | 0.41 | 0.17 | 0.28 | 1.15 | 0.33 | 1.15 |

| Mother’s education (HS) | ||||||||

| Less than HS | 2.55† | 1.36 | 0.48 | 1.25 | 0.74 | 1.24 | 0.72 | 1.24 |

| Some college | 1.05 | 0.90 | 1.11 | 0.79 | 1.11 | 0.78 | 1.05 | 0.78 |

| College or more | −1.28 | 1.00 | −0.30 | 0.89 | −0.17 | 0.88 | −0.18 | 0.88 |

| Gainfully active | −3.13*** | 0.87 | −1.65† | 0.84 | −1.32 | 0.84 | −1.37 | 0.84 |

| Relationship Status ( Single) | ||||||||

| Dating | −1.53* | 0.77 | −1.52* | 0.68 | −1.43* | 0.67 | −1.50 | 0.67 |

| Cohabiting | 0.32 | 2.04 | −2.75 | 1.85 | −2.98 | 1.83 | −2.99 | 1.82 |

| Married | 0.56 | 3.11 | −2.59 | 2.85 | −3.31 | 2.86 | −3.07 | 2.85 |

| Children | 1.84 | 1.15 | 0.85 | 1.14 | 0.78 | 1.13 | 0.85 | 1.13 |

| Employment problems x Returned to the parental home | 4.12* | 1.88 | ||||||

| R2 | .30 | .32 | .33 | |||||

p < .01;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

Results

Descriptive Analysis

Table 1 displayed descriptive statistics for all variables by parent residence type. About one-fifth (19.49%) of the sample of emerging adults returned to their parental home (boomeranged), one-third (34.84%) lived with their parents continuously, and about half (45.67%) were living independently. One way to view these findings is to consider the subsample of emerging young adults living with their parents; the majority (64%) had not yet left home and 36% of had moved out and returned home (boomeranged). Another way to consider these findings is that among the subsample of emerging adults who have left their parental home, nearly 30% returned home and are currently residing with parents (boomeranged) and 70% have remained on their own. Thus, ignoring these boomeranging emerging adults results in an overly simplistic portrait of their residential experiences.

Mean levels of depressive symptoms were significantly higher among emerging adults who returned home than those who lived independently or never left their parental home. This finding underscores the importance of distinguishing between these groups. Mean levels of prior depressive symptoms, however, did not differ by parent residence type. Table 1 also included the distribution of the covariates by parent residence type. Because living arrangement and well-being were likely related to a number of individual characteristics, including prior depression, we examined regression models to assess living arrangements and depressive symptoms, net of these factors.

Zero-Order and Multivariate Analyses

Parent Residence Dynamics and Depressive Symptoms

Table 2 shows at the bivariate level, staying in the parental home and living independently were significant and negatively related to depressive symptoms. Thus, those returning to the parental home (boomeranging) as compared to staying or living independently experienced higher levels of depressive symptoms. Supplemental models examined the association between living arrangement and depressive symptoms with “stayed in the parental home” as the omitted category. Results of those models revealed that those who stayed at home and those who lived independently reported significantly lower levels of depression than those who returned, and additionally, the relationship between returning to the parental home and depressive symptoms was significant and positive. The relationships between staying in the parental home, living independently, and depressive symptoms persisted net of prior depressive symptoms (Model 2). This supported the descriptive profile presented in Table 1 indicating that the 3 groups did not differ in initial levels of depressive symptoms, suggesting that the observed significant association between depressive symptoms and parent residence type was not due to preexisting levels.

In terms of the control variables, parental closeness, gender, gainful activity, and relationship status exerted independent effects on depressive symptoms. Emerging adults who reported higher levels of parental closeness and those who were either employed or attending school reported lower levels of depression. Consistent with prior work, women reported higher depressive symptoms. Emerging adults who were in a relationship, dating, cohabiting or married, scored lower on depressive symptoms. Including relationship status partially mediated the association between living arrangement and depressive symptoms. This finding suggests that relationship status (cohabiting or married emerging adults less often lived with their parents) partially explained the association between returning to the parental home and depressive symptoms.

We tested interactions to determine whether age influenced the effect of parent residence type on depressive symptoms. Cross product terms of parent residence type and age were entered in separate models predicting depressive symptoms (results not shown). The interactions were not significant suggesting that the association between parent resident type and depressive symptoms was similar across the age range in the study (18–24).

In summary, the results in Table 2 provided evidence of an association between returning to the parental home and depressive symptoms. Furthermore, this relationship was not explained by adolescent levels of depression. The key correlates associated with depressive symptoms, net of living arrangements, were parental closeness, gender, gainful activity, and relationship status. The significant negative relationships between staying in the parental home and living independently versus returning to the parental home and depressive symptoms were partially explained by relationship status. That is, involvement in a romantic relationship--whether dating, cohabiting or married--was negatively related to depressive symptoms, and those returning to the parental home were more likely to be single. Nevertheless, the relationship between staying in the parental home and depression remained significant net of controls for prior levels of depression, parental closeness, sociodemographic characteristics, gainful activity, relationship status, and number of children.

Rationales to Reside with Parents

We examined the role of rationales to reside with parents among emerging adults coresiding with parents at the time of the fourth interview (n = 471). Figure 1 provided a graphic representation of the percent of respondents who cited each of the rationales for coresiding by living arrangement. These differences were statistically significant indicating that individuals who moved back with parents were more likely to report employment problems as rationales to coreside, and less likely to cite enjoy living with parents, needed parents’ help, couldn’t support myself, and wanted to save money. One exception was that coresident emerging adults, including those who stayed and returned to the parental home, were similarly likely to attribute their coresidential decisions to their parents needing help. These findings further support distinguishing coresiding emerging adults into returners and stayers. However, although these rationales were related to parent residence type, only employment problems and enjoy living with parents were associated with levels of depressive symptoms, and thus regression models are limited to these two rationales representing utilitarian and intrinsic reasons to coreside.

Results of the regression models shown in Table 3 included bivariate relationships between all independent variables and depressive symptoms in the first column. Individuals returning to the parental home, compared to never leaving the parental home, reported higher depressive symptoms. Those who reported they enjoyed living with their parents reported lower depressive symptoms while those who had employment problems reported higher depressive symptoms.

Model 2 presented the association between living arrangement and depressive symptoms, net of prior depression and controls for the parent-child relationship, sociodemographic characteristics, family factors, and adult status characteristics. Among coresiding emerging adults, both living arrangement and adolescent depression were positively related to depressive symptoms. Model 3 introduced the rationales for living with parents as a block and the significant relationship between returning home and depressive symptoms was attenuated. Respondents who cited enjoying living with parents as a rationale for coresidence reported lower levels of depressive symptoms net of other factors, but those who endorsed employment factors as a rationale shared similar levels of depressive symptoms as their counterparts who did not offer employment reasons as a rationale for living with parents. Further analyses tested the meditational hypothesis by examining the indirect effects of parent residence type on depressive symptoms through rationales to reside with parents. Whereas typical tests of mediation are unable to simultaneously test multiple mediators or account for the effects of other covariates, we estimated the path coefficients in a multiple mediator model adjusting all paths for the potential influence of study covariates not proposed to be mediators in the model (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). Findings revealed that rationales partially mediated the association between returning home and depressive symptoms (total indirect effect = 1.50, p < .001), and that this was due to enjoy living with parents (Z = 4.11, p < .001) and employment problems (Z = 1.82, p < .10).

The moderating hypothesis evaluated whether the association between returning to the parental home and depressive symptoms varied according to rationales to reside with parents. At the bivariate level there was a strong positive association between employment problems and depressive symptoms. We examined whether the effect of returning to the parental home differed for those who cited employment problems as a rationale for their return as compared to those who did not cite such problems (Model 4). The interaction term indicated that the effect of returning home on depressive symptoms was significantly more positive for those citing employment problems as a rationale for returning home. Returning home was associated with depressive symptoms only for emerging adults who reported employment problems. Enjoy living with parents had a similar association with depressive symptoms regardless of whether they had never left or returned home.

Discussion

The prevalence of adult children living with parents is increasing, and in response, scholars are beginning to focus on the relationship between coresidence and a number of outcomes related to the well-being of emerging adults. A significant limitation of much of the prior work was that it employed data that did not differentiate between emerging adults who never left the parental home and those who returned after a period of living independently, thus giving limited attention to the varying pathways to coresidence among emerging adults, and providing an incomplete exploration of the association between coresidence and well-being. Overall, at the time of interview about one-fifth of emerging adults had boomeranged or moved back in with their parents. Among emerging adults living with their parents, we find a substantial share, 36%, boomeranged or returned to their parental home. In this study, we distinguished between emerging adults who never left their parental home and those who returned to unmask important variation in the potential impliations of coresidence. Recent studies have concluded that coresiding emerging adults are faring quite well—they were generally satisfied with their living arrangements and optimistic about the future (Pew Research Center, 2012). The findings from the current investigation suggest that although emerging adults who returned home and those who stayed in the parental home shared a common residential status, their experiences were often quite distinct. Additionally, the limited amount of work examining the relationship between living arrangement and well-being often has failed to control for individual characteristics that were likely associated with both living arrangement and depressive symptoms. Because of the longitudinal nature of the TARS data, we were able to control for an important factor, prior levels of depressive symptoms measured during adolescence.

Moreover, most studies examining coresidence primarily examined relationships between young adults’ living arrangements and a number of structural and demographic factors. Findings from this research suggest that there is an association between coresidence and well-being, but do little in the way of describing the processes or mechanisms driving this relationship. Our study also incorporated rationales for residing with parents, and examined whether these rationales both mediated and moderated the relationship between parent residence dynamics and depressive symptoms. We argued that rationales to reside with parents represent an important conceptual bridge between emerging adults’ living arrangements and depressive symptoms. In this study, such rationales were associated with depressive symptoms. Additionally, rationales to coreside partially explained the association between living arrangements and depressive symptoms, and in the case of employment problems, exacerbated the influence of parent residence dynamics on depressive symptoms. These findings contribute to our understanding of the great diversity in pathways to adulthood and emphasize the importance of examining how a broader range of experiences relate to emerging adults’ well-being.

Although these analyses contributed to prior work that has largely been limited to general assessments of coresidence and well-being, there were some limitations. The current study explored a range of rationales to coreside with parents, however, only two were related to emerging adult depressive symptoms and included in regression models. Future work should encompass a broader range of rationales. Beyond rationales, future work should look to the influence of cultural norms on the nature and timing of moves back to, and away from, the parental home. This study provided a cross-sectional examination of the relationships between parent residence type, rationales to coreside with parents, and depressive symptoms. Future research should consider how these patterns develop longitudinally. Additionally, this study examined a small piece of the young adult period (ages 18–24). Future work should consider the impact of age on patterns of leaving and returning home among older young adults. In these analyses, age did not emerge as a significant predictor either of depression net of living arrangement, nor did the impact of living arrangement vary as a function of age. As emerging adults move forward in the transition to adulthood, age may become an increasingly important factor in the relationship between living arrangement and well-being.

Recent evidence indicates that the economic recession has been particularly devastating for emerging adults, as they have often found themselves among the last hired and first fired. Thus, the nature of the economic situation of the emerging adult population may further delay the home-leaving process, or may require moves home among those who had at one time established independent residences. Although the trend in increasing coresidence has been steady over the course of the pre- and post-recession periods, future work should focus particular attention on the implications of coresidence for depressive symptoms in the post-recession era, including specific catalysts or motivations for such an arrangement. Furthermore, one of the primary objectives of the current investigation was to emphasize the varying pathways to coresidence. We find that as a group coresident emerging adults are not only diverse, but that the condition of coresidence often results from different causes. An important counterpoint to our findings, however, is that coresidence may prove beneficial under certain circumstances. Thus, had we compared coresident emerging adults to their counterparts who live independently, we may have found that coresiders were “better off” in terms of depressive symptoms under certain conditions—such as following a loss of employment. Data limitations precluded this comparison, however future work should consider factors that buffer the effect of living arrangements on depressive symptoms, including circumstances under which coresidence alleviates depressive symptoms.

Our paper provides in important starting point. It would be useful to know how parents view these living arrangements as it is likely that their attitudes, whether positive or negative, would affect emerging adults’ well-being. Also, the nature of the move itself (whether it was planned or unexpected) may have different consequences for the well-being of parent(s) and their emerging adult children, as well as the parent-child relationship. After parents’ adult children move out and establish independent residences, they may restructure their lives accordingly. This may include changes to the home itself (i.e., repurposing of the child’s room, downsizing), or changes in the allocation of family resources. Unexpected moves home may place a larger burden on parents, as compared to prearranged periods of coresidence. Future research should examine the social psychological complexity that young adults experience by virtue of the move, and the ways in which that may complicate the parent-child relationship.

Lastly, the real life difficulties encountered by emerging adults are undoubtedly the key contributing factors to emotional difficulties. Thus, employment problems, divorce, and a long roster of other negative life events may be directly implicated to an unknown extent in the higher levels of depressive symptoms observed in the subset of individuals who returned to the parental home. However, it appears that this shift in living arrangement is not inconsequential, but rather adds to the negative portrait and contributes to lower levels of overall well-being. By definition, this group of individuals had enacted a plan for independent living, which may have included reliance on their own resources or forging a relationship with an adult intimate partner. Consequently, coresidence may be perceived as a “regression” or form part of a downward trajectory to a greater extent among boomerangs as compared to their peers who are either stably independent or stably coresiding with parents. In terms of emerging adults’ future orientation, if there is an increase in depressive symptoms following coresidence—particularly when such arrangements are precipitated by negative unexpected life events (i.e., job loss)—this could affect their feelings of efficacy and ability to pursue educational/career opportunities, actively seek romantic partners, and maintain healthy relationships with others.

Young people are the most diverse group in the United States (Settersten, 2012), and thus we should not expect their experiences to be unidimensional. Although the broad picture may indicate that coresidence is inconsequential for the well-being of young adults, this perspective does not encompass the potential for variability in the link between living arrangement and well-being, nor does it provide potential mechanisms associated with variation in this relationship. The current study demonstrated that living arrangements are associated with emerging adults’ emotional well-being. Once these varied pathways and rationales were taken into account, the analyses specified a number of mechanisms that were systematically associated with both the living arrangements of young adults and well-being, providing an important starting point for future work in this area.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (HD036223 and HD044206), and by the Center for Family and Demographic Research, Bowling Green State University, which has core funding from The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R24HD050959-01).

References

- Arnett JJ. Young people’s conceptions of the transition to adulthood. Youth & Society. 1997;29:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Learning to stand alone: The contemporary American transition to adulthood in cultural and historical context. Human Development. 1998;41:295–315. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Conceptions of the transition to adulthood: Perspectives from adolescence through midlife. Journal of Adult Development. 2001;8(2):133–143. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist. 2000;55(5):469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teems through the twenties. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ, Schwab J. Thriving, struggling, & hopeful. The Clark University Poll of Emerging Adults 2012. 2012 http://www.clarku.edu/clark-poll-emerging-adults/pdfs/clark-university-poll-emerging-adults-findings.pdf.

- Arnett JJ, Schwab J. Parents and their grown kids: Harmony, support, and (occasional) conflict. The Clark University Poll of Parents of Emerging Adults, 2013. 2013 http://www.clarku.edu/clark-poll-emerging-adults/pdfs/clark-university-poll-parents-emerging-adults.pdf.

- Aquilino WS. Family structure and home-leaving: A further specification of the relationship. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1991;58:293–310. [Google Scholar]

- Buchman M. The script of life in modern society: Entry into adulthood in a changing world. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Buck N, Scott J. She’s leaving home: But why? An analysis of young people leaving the parental home. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1993;55(4):863–874. [Google Scholar]

- Britton ML. Race/ethnicity, attitudes, and living with parents during young adulthood. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2013;75:995–1013. [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin AJ, Scabini E, Rossi G. Still in the nest: Delayed home leaving in Europe and the United States. Journal of Family Issues. 1997;18:572–575. [Google Scholar]

- DaVanzo J, Goldscheider FK. Coming home again: Returns to the parental home of young adults. Population Studies: A Journal of Demography. 1990;44(2):241–255. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J. Income effects across the life-span: Integration and interpretation. In: Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J, editors. Consequences of Growing Up Poor. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 1997. pp. 596–610. [Google Scholar]

- Evenson RJ, Simon RW. Clarifying the relationship between parenthood and depression. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2005;46(1):341–358. doi: 10.1177/002214650504600403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg FF. On a new schedule: Transitions to adulthood and family change. The Future of Children. 2010;20(1):67–87. doi: 10.1353/foc.0.0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg FF. The sociology of adolescence and youth in the 1990’s: A critical commentary. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:896–910. [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg FF, Kennedy S, McLoyd VC, Rumbaut R, Settersten RA. Growing up is harder to do. Contexts. 2004;3(3):33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Goldscheider F, Goldscheider C. The changing transition to adulthood: Leaving and returning home. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Goldscheider F, Goldscheider C, St Clair P, Hodges J. Changes in returning home in the United States, 1925–1985. Social Forces. 1999;78(2):695–728. [Google Scholar]

- Hallquist SP, Cuthbertson C, Killeya-Jones L, Halpern CT, Harris KM. Living arrangements in young adulthood: Results from Wave IV of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Add Health Research Brief prepared for the Carolina Population Center. 2011 Nov;(1) [Google Scholar]

- Hartnett CS, Furstenberg FF, Birditt KS, Fingerman KL. Parental support during young adulthood: Why does assistance decline with age? Journal of Family Issues. 2013;34(7):975–1007. doi: 10.1177/0192513X12454657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haveman R, Wolfe B, Spauldng J. Childhood events and circumstances influencing high school completion. Demography. 1991;28:133–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtforth MG, Thomas A, Caspar F. Interpersonal Motivation. In: Horowitz LM, Strack S, editors. Handbook of Interpersonal Psychology. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2011. pp. 107–122. [Google Scholar]

- Kins E, Beyers W. Failure to launch, failure to achieve criteria for adulthood? Journal of Adolescent Research. 2010;25(5):743–777. [Google Scholar]

- Kins E, Beyers W, Soenens B, Vansteenkiste M. Patterns of home leaving and subjective well-being in emerging adulthood: The role of motivational processes and parental autonomy support. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45(5):1416–1429. doi: 10.1037/a0015580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod JD, Owens TJ. Psychological well-being in the early life course: Variations by socioeconomic status, gender, and race/ethnicity. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2004;67(3):257–278. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell BA, Wister A, Gee EMT. The ethnic and family nexus of homeleaving and returning among Canadian young adults. The Canadian Journal of Sociology. 2004;29(4):543–575. [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer JT. Transition to adulthood, parental support, and early adult well-being: Recent findings from the youth development study. In: Booth A, Brown SL, Landale NS, Manning WD, McHale SM, editors. Early Adulthood in a Family Context. Vol. 2. New York, NY: Springer; 2012. pp. 27–34. National Symposium on Family Issues. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson LJ, Barry CM. Distinguishing features of emerging adulthood: The role of self-classification as an adult. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2005;20(2):242–262. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson LJ, Padilla-Walker LM, Carroll JS, Madsen SD, Barry CM, Badger S. “If you want me to treat you like an adult, start acting like one!” Comparing the criteria that emerging adults and their parents have for adulthood. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21(4):665–674. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Painter G. What happens to household formation in a recession? Research Institute for Housing America. 2010 Special Report. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. The boomerang generation: Feeling Ok about living with mom and dad. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center Social and Demographic Trends project; 2012. Mar, http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2012/03/15/the-boomerang-generation.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. A rising share of young adults live in their parents’ home. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center Social and Demographic Trends project; 2013. Aug, http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/files/2013/07/SDT-millennials-living-with-parents-07-2013.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. The rising cost of not going to college. 2014 http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2014/02/11/the-rising-cost-of-not-going-to-college/

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40(3):879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian Z. [accessed September 16, 2012];During the Great Recession, more young adults lived with parents. Census Brief prepared for US 2010 Project. 2010 http://www.s4.brown.edu/us2010.

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–481. [Google Scholar]

- Settersten RA. A time to leave home and a time never to return? Age constraints on the living arrangements of young adults. Social Forces. 1998;76(4):1373–1400. [Google Scholar]

- Settersten RA. The contemporary context of young adulthood in the USA: From demography to development, from private troubles to public issues. In: Booth A, Brown SL, Landale NS, Manning WD, McHale SM, editors. Early Adulthood in a Family Context. 2012. National Symposium on Family Issues 2. [Google Scholar]

- Settersten RA, Ray B. What’s going on with young people today? The long and twisting path to adulthood. The Future of Children. 2010;20(1):19–41. doi: 10.1353/foc.0.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan MJ. Pathways to adulthood in changing societies: Variability and mechanisms in life course perspective. Annual Review of Sociology. 2000;26:667–692. [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan MJ, Porfeli EJ, Mortimer JT, Erickson LD. Subjective age identity and the transition to adulthood: When do adolescents become adults? In: Settersten RA, Furstenberg FF, Rumbaut RG, editors. On the Frontier of Adulthood: Theory, Research, and Public Policy. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2005. pp. 225–255. The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur foundation series on mental health and development. [Google Scholar]

- Swartz TT, Kim M, Uno M, Mortimer JT, O’Brien K. Safety nets and scaffolds: Parental support in the transition to adulthood. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2011;73:414–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00815.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Young adults living at home: 1960 to present. 2009 www.census.gov/population/www/socdemo/hh-fam.html#cps.

- U.S. Census Bureau. Table MS-2. Estimated median age at first marriage, by sex: 1890 to the Present. 2012 www.census.gov/hhes/families/files/ms2.csv.

- Wang W, Morin R. Recession brings many young people back to the nest: Home for the holidays and every other day. [accessed October 13, 2012];Pew Research Center. 2009 http://pewsocialtrends.org/assets/pdf/home-for-the-holidays.pdf.

- Ward RA, Spitze G. Consequences of parent-adult child coresidence: A review and research agenda. Journal of Family Issues. 1992;13(4):553–572. [Google Scholar]

- Ward RA, Spitze G. Will the children ever leave?: Parent-child coresidence and plans. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:514–539. [Google Scholar]

- White L. Coresidence and leaving home: Young adults and their parents. Annual Review of Sociology. 1994;20:81–102. [Google Scholar]

- Whiteman SD, McHale SM, Crouter AC. Family relationships from adolescence to early adulthood: Changes in the family system following firstborns’ leaving home. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2011;21:461–474. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00683.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]