Abstract

Recently, the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Research Network and Asian Cancer Research Group provided a new classification of gastric cancer (GC) to aid the development of biomarkers for targeted therapy and predict prognosis. We studied associations between genetically aberrant profiles of cancer-related genes, environmental factors, and histopathological features in 107 paired gastric tumor-non-tumor tissue GC samples. 6.5% of our GC cases were classified as the EBV subtype, 17.8% as the MSI subtype, 43.0% as the CIN subtype, and 32.7% as the GS subtype. The distribution of four GC subgroups based on the TCGA and our dataset were similar. The MSI subtype showed a hyper-mutated status and the best prognosis among molecular subtype. However, molecular classification based on the four GC subtypes showed no significant survival differences in terms of overall survival (p= 0.548) or relapse-free survival (RFS, p=0.518). The P619fs*43 in ZBTB20 was limited to MSI group (n= 5/19, 26.3%), showing similar trends observed in TCGA dataset.

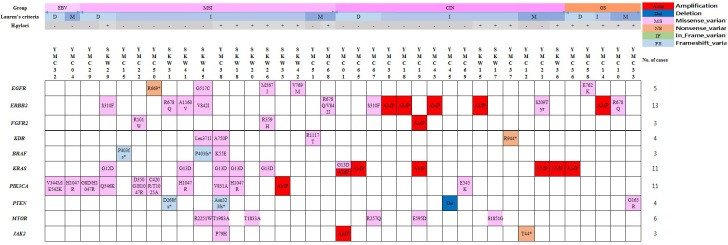

Genetic alterations of the RTK/RAS/MAPK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways were detected in 34.6% of GC cases (37 individual cases). We also found two cases with likely pathogenic variants (NM_004360.4: c. 2494 G>A, p.V832M) in the CDH1 gene.

Here, we classified molecular subtypes of GC according to the TCGA system and provide a critical starting point for the design of more appropriate clinical trials based on a comprehensive analysis of genetic alterations in Korean GC patients.

Keywords: gastric cancer, molecular subtyping, germline mutation, somatic mutaiton, targeted sequencing

INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer (GC) is ranked fifth for cancer incidence and second for cancer deaths, and one in 36 men and 1 in 84 women develop stomach cancer before age 79 [1]. The histologic classification of gastric carcinoma has been based on the Lauren [2] and 2010 WHO classification systems, which recognize four histological subtypes [3]. Neither the Lauren nor the WHO system is particularly clinically useful, as their prognostic and predictive capabilities cannot adequately guide patient management. Thus, new classifications are needed for GC to provide insights into pathogenesis and the identification of new biomarkers and novel treatment targets [4]. Recently, advances in technology and high-throughput analysis have improved our understanding of the genetic basis of GC. To provide a roadmap for patient stratification and trials of targeted therapies, the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Research Network has characterized 295 primary gastric adenocarcinomas and proposed a new classification of four different tumor subtypes of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-positive, microsatellite instability (MSI), genomically stable (GS), and chromosomal instability (CIN) subtypes. [5]. The Asian Cancer Research Group (ACRG) also provided a new classification for GC, identifying four subtypes: MSI, MSS/EMT, MSS/TP53 (+), and MSS/TP53(–). One of the most important aspects of the ACRG classification is that it correlates the molecular subtypes with clinical prognosis [6].

Helicobacter pylori has been accepted as a causative organism in GC [7, 8], and EBV is also now regarded as a GC-causing infectious agent. The original type of EBV-infected GC makes up 5-10% of all GC cases [9, 10]. The vast majority of GC arise sporadically, and an inherited component contributes to <3% of gastric cancers [11, 12]. The GC is a heterogeneous disease characterized by epidemiologic and histopathologic differences across countries [7, 8, 13, 14]. Here, we investigated germline mutations in CDH1, MSH2, MLH1, TP53, APC, and STK11, which are associated with hereditary diffuse gastric cancer, hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer, Li–Fraumeni syndrome, familial adenomatous polyposis, and Peutz–Jeghers syndrome, respectively [11, 12, 15–19]. Furthermore, we studied associations between the genetic aberrant profiles of cancer-related genes, environmental factors (EBV and H. pylori), and histopathological features in Korean GC patients. We also classified molecular subtypes of Korea GC.

RESULTS

Clinical and pathological findings of 107 Korean GC patients

The male to female ratio was 2:1 with median patient age of 70 years (range, 32-90). The intestinal type, diffuse type, and mixed type by Lauren classification accounted for 54.2%, 26.2%, and 19.6%, respectively. In addition, for GC classified according to the 2010 WHO classification, the tubular type (64.5%) was observed with the highest frequency, while the poorly cohesive type and mixed type accounted for 13.1% and 15.0%, respectively. More than half of the tumors were located in the antrum or antrum body, while about 7.5% were located in the cardia and gastroesophageal junction. Fifty-two cases (48.6%) were in stages III-IV, and 66 (61.7%) were H.pylori-positive. The clinicopathological findings of the 107 GC patients are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Clinicopathological characteristics of patients with gastric cancer (n=107).

| Characteristics | Number |

|---|---|

| Age (year) | |

| Median (range) | 70 (32 ∼ 90) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 36 (33.6%) |

| Male | 71 (66.4%) |

| Lauren class | |

| Diffuse | 28 (26.2%) |

| Intestinal | 58 (54.2%) |

| Mixed | 21 (19.6%) |

| WHO class | |

| Mucinous | 3 (2.8%) |

| Tubular | 69 (64.5%) |

| Poorly cohesive | 14 (13.1%) |

| Mixed (Tubular_Poorly cohesive) | 16 (15.0%) |

| Uncommon histologic variants | 5 (4.7%) |

| pT stage | |

| T1a/T1b | 9 (8.4%)/15 (14.0%) |

| T2 | 11 (10.3%) |

| T3 | 38 (35.5%) |

| T4a/T4b | 33 (30.8%)/1 (0.9%) |

| pN stage | |

| N0/N1/N2/N3 | 40 (37.4%)/16 (15.0%)/20 (18.7%)/31 (29.0%) |

| M stage | |

| M0/M1 | 102 (95.3%)/5 (4.7%) |

| AJCC stage | |

| Stages IA/IB | 18 (16.8%)/11 (10.3%) |

| Stages IIA/IIB | 13 (12.1%)/13 (12.1%) |

| Stages IIIA/IIIB/IIIC | 17(15.9%)/11 (10.3%)/19 (17.8%) |

| Stage IV | 5 (4.7%) |

| Anatomical regions | |

| GEJ_Cardia | 8 (7.5%) |

| Fundus_Body | 36 (34.3%) |

| Antrum | 54 (50.5%) |

| Antrum_Body | 5 (4.7%) |

| Pylorus | 3 (2.8%) |

| Diffuse | 1 (0.9%) |

| Epstein-Barr virus infection | |

| Negative | 100 (93.5%) |

| Positive | 7 (6.5%) |

| Microsatellite instability(MSI) | |

| MSS | 88 (82.2%) |

| MSI-I | 4 (3.7%) |

| MSI-H | 15 (14.0%) |

| H. pylori infection | |

| Negative | 41 (38.3%) |

| Positive | 66 (61.7%) |

Abbreviations: GEJ, gastroesophageal junction; H. pylori, Helicobacter pylori; pT stage, pathological assessment of the primary tumor; pN stage, pathological assessment of the regional lymph nodes.

Germline variation analysis of hereditary cancer-predisposing syndrome

A total of 30 germline variants were observed in TP53, STK11, ALK, APC, MSH2, MLH1, and CDH1 (Table 2). Among these, 16 variants, 12 variants, and 2 variants were classified as 'Benign or Likely Benign,' 'VUS,' and 'Likely pathogenic,' respectively. Two cases had a likely pathogenic variant (p.V832M) in CDH1 gene.

Table 2. Germline SNPs in TP53, STK11, ALK, APC, MSH2, MLH1, and CDH1 genes of 107 Korean gastric cancer patients.

| Sample | Chromosome | Start | End | Ref | Alter | Gene | Transcript ID | Amino acid change | Total depth | VAF(%)(1)a | VAF (%)(2)b | Clinical significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YMC 54 | 2 | 29449820 | 29449820 | G | A | ALK | NM_004304.4 | p.T1012M | 637 | 48.51% | 60.36% | Benign |

| YMC 7 | 2 | 29449820 | 29449820 | G | A | ALK | NM_004304.4 | p.T1012M | 208 | 55.77% | 43.83% | Benign |

| YMC 70 | 2 | 29449820 | 29449820 | G | A | ALK | NM_004304.4 | p.T1012M | 755 | 52.58% | 57.85% | Benign |

| SKW 18 | 2 | 29519923 | 29519923 | G | A | ALK | NM_004304.4 | p.L550F | 155 | 38.06% | 55.39% | VUS |

| YMC 13 | 5 | 112177778 | 112177778 | A | C | APC | NM_001127511.2 | p.K2145Q | 151 | 52.32% | 33.74% | Benign |

| YMC 24 | 5 | 112178865 | 112178865 | G | A | APC | NM_001127511.2 | p.R2507H | 1142 | 47.90% | 49.52% | VUS |

| SKW 38 | 5 | 112176548 | 112176548 | G | C | APC | NM_001127511.2 | p.A1735P | 628 | 45.86% | 47.30% | VUS |

| SKW 21 | 5 | 112173895 | 112173895 | A | C | APC | NM_001127511.2 | p.E850D | 147 | 55.78% | 50.93% | Benign |

| YMC 29 | 16 | 68867247 | 68867247 | G | A | CDH1 | NM_004360.4 | p.V832M | 1337 | 52.21% | 49.75% | Likely pathogenic |

| YMC 37 | 16 | 68867247 | 68867247 | G | A | CDH1 | NM_004360.4 | p.V832M | 1498 | 50.73% | 46.41% | Likely pathogenic |

| SKW 16 | 16 | 68856080 | 68856080 | C | G | CDH1 | NM_004360.4 | p.L630V | 928 | 43.74% | 40.61% | Benign |

| SKW 15 | 16 | 68856080 | 68856080 | C | G | CDH1 | NM_004360.4 | p.L630V | 827 | 49.33% | 71.46% | Benign |

| YMC 53 | 3 | 37053562 | 37053562 | C | T | MLH1 | NM_000249.3 | p.R217C | 1397 | 46.96% | 50.40% | VUS |

| YMC 55 | 3 | 37042521 | 37042521 | T | G | MLH1 | NM_000249.3 | p.S95A | 233 | 39.06% | 30.52% | VUS |

| YMC 6 | 3 | 37067240 | 37067240 | T | A | MLH1 | NM_000249.3 | p.V384D | 578 | 48.79% | 44.85% | Benign |

| YMC 70 | 3 | 37067240 | 37067240 | T | A | MLH1 | NM_000249.3 | p.V384D | 547 | 51.55% | 47.99% | Benign |

| YMC 14 | 3 | 37053562 | 37053562 | C | T | MLH1 | NM_000249.3 | p.R217C | 1409 | 45.71% | 51.65% | VUS |

| YMC 22 | 3 | 37067240 | 37067240 | T | A | MLH1 | NM_000249.3 | p.V384D | 862 | 99.54% | 100% | Benign |

| YMC 3 | 3 | 37090506 | 37090506 | C | A | MLH1 | NM_000249.3 | p.Q701K | 369 | 51.49% | 41.29% | Benign |

| YMC 4 | 3 | 37089022 | 37089022 | C | G | MLH1 | NM_000249.3 | p.L582V | 364 | 48.63% | 57.47% | VUS |

| YMC 37 | 3 | 37053562 | 37053562 | C | T | MLH1 | NM_000249.3 | p.R217C | 1315 | 49.20% | 49.76% | VUS |

| YMC 48 | 3 | 37067240 | 37067240 | T | A | MLH1 | NM_000249.3 | p.V384D | 899 | 43.38% | 44.61% | Benign |

| SKW 31 | 3 | 37053562 | 37053562 | C | T | MLH1 | NM_000249.3 | p.R217C | 294 | 55.78% | 39.71% | VUS |

| YMC 66 | 2 | 47656972 | 47656972 | C | T | MSH2 | NM_000251.2 | p.L390F | 197 | 56.85% | 52.78% | Benign |

| YMC 15 | 2 | 47656972 | 47656972 | C | T | MSH2 | NM_000251.2 | p.L390F | 1281 | 46.68% | 79.62% | Benign |

| YMC 28 | 2 | 47630344 | 47630344 | C | A | MSH2 | NM_000251.2 | p.P5Q | 231 | 53.25% | 86.79% | VUS |

| YMC 5 | 2 | 47637371 | 47637371 | A | G | MSH2 | NM_000251.2 | p.I169V | 711 | 51.34% | 45.12% | Likely benign |

| YMC 48 | 2 | 47656972 | 47656972 | C | T | MSH2 | NM_000251.2 | p.L390F | 692 | 51.30% | 53.31% | Benign |

| SKW 41 | 2 | 47703564 | 47703564 | G | A | MSH2 | NM_000251.2 | p.M688I | 993 | 52.57% | 50.83% | VUS |

| SKW 40 | 17 | 7578209 | 7578209 | G | A | TP53 | NM_000546.5 | p.H214Y | 168 | 39.29% | 59.58% | VUS |

a, tumor tissue; b, matched non-tumor tissue.

Abbreviation: Ref, reference allele; Alter, Altered allele; VAF, Variant allele frequency; VUS, a variant of unknown significance.

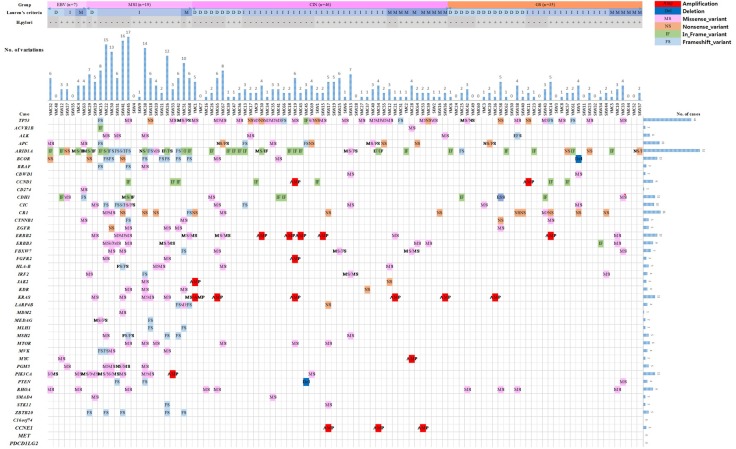

Molecular profile of gastric cancer with a 43 gene cancer panel

To identify driver genes [20] causally linked to tumorigenesis in Korea GCs, variants were extracted from targeted sequencing with a 43 gene cancer panel applied to 107 tumor and matched non-tumor tissues. After mutation calling and stringent filtrations, we identified 317 single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) on coding sequences that included missense variations (n=164, 51.7%), trunc (nonsense and frameshift) variations (n= 110, 34.7%), in-frame variations (n= 42, 13.2%), and splicing site variations (n=1, 0.3%) (Supplementary Table 2). Somatic variants detected in each gene for each sample were summarized in Supplementary Table 3. Among the 43 genes, we discovered 39 genes that were mutated in one or more individual samples. Among the 107 samples, TP53 (38.3%), ARID1A (36.4%), CR1 (15.0%), APC (11.2%), BCOR (11.2%), CDH1 (10.3%), CIC (9.3%), PIK3CA (9.3%), ERBB3 (8.4%), RHOA (8.4%), ERBB2 (7.5%), CCND1 (6.5%), FBXW7 (6.5%), ALK (5.6%), KRAS (5.6%), and MTOR (5.6%) were identified (Supplementary Table 3). Somatic variants were detected in relatively low frequencies (less than 5%) on the CTNNB1, EGFR, HLA-B, MSH2, PGM5, ZBTB20, IRF2, KDR, LARP4B, MVK, BRAF, PTEN, ACVR1B, CBWD1, FGFR2, JAK2, MEDAG, MLH1, SMAD4, STK11, CD274, MDM2, and MYC genes in this study. We did not detect any somatic variants on the C16orf74, CCNE1, PDCD1LG2, or MET genes (Supplementary Table 3).

Among 317 somatic variants, 110 (34.7%) were recurrently detected in this study (Table 3). According to the results of somatic variants, p.Gln1334del/dup or p.Asp1850ThrfsTer33 in ARID1A, p.Arg2194Ter in CR1, p.Glu280del in CCND1, p.Leu15del in CDH1, p.Arg678Gln in ERBB2, p.Gly13Asp in KRAS, p.His1047Arg in PIK3CA, and p.Pro619LeufsTer43 in ZBTB20 were recurrently detected in more than four individual cases (Table 3). Twenty-two copy number variation (CNV)s were identified in the BCOR (n=1), CCND1 (n=2), CCNE1 (n=3), ERBB2 (n=5), FGFR2 (n=1), KRAS (n=6), MYC (n=1), PIK3CA (n=1), PTEN (n=1), and JAK2 (n=1) (Figure 1).

Table 3. The location-specific recurrence of somatic variants in the 43 cancer panel genes.

| Gene | Variantsa | Mutated samples | % of mutated samples | COSMIC counts | COSMIC ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APC | p.Glu1464ValfsTer8 | 2 | 1.90% | 45 | COSM1432412; COSM19694; COSM41622; COSM41622; COSM41622; COSM5030795 |

| ARID1A | p.Asp1850ThrfsTer33 | 5 | 4.70% | 27 | COSM1341426; COSM133001; COSM1666860 |

| ARID1A | p.Gln1334del/dup | 23 | 21.50% | 23 | COSM1341408; COSM298325; COSM1578346; COSM133030; COSM51218; COSM1238047 |

| ARID1A | p.Gly87del | 2 | 1.90% | (-) | |

| BCOR | p.Gln1174ThrfsTer8 | 3 | 2.80% | 5 | COSM1683572; COSM3732385 |

| BRAF | p.Pro403LeufsTer8 | 2 | 1.90% | 7 | COSM1448632; COSM5347158; COSM5347157 |

| CCND1 | p.Glu280del | 7 | 6.50% | 3 | COSM931394 |

| CDH1 | p.Leu15del | 5 | 4.70% | (-) | |

| CR1 | p.Arg2194Ter | 10 | 9.30% | 20 | COSM301989 |

| ERBB2 | p.Arg678Gln | 4 | 3.70% | 23 | COSM978678; COSM436498 |

| ERBB2 | p.Ser310Phe | 2 | 1.90% | 51 | COSM48358; COSM1666868 |

| ERBB2 | p.Val842Ile | 2 | 1.90% | 26 | COSM14065; COSM1666633 |

| ERBB3 | p.Val104Met | 2 | 1.90% | 21 | COSM20710 |

| FBXW7 | p.Arg385His | 3 | 2.80% | 41 | COSM117308 |

| HLA-B | p.Glu69Val | 2 | 1.90% | 3 | COSM4598273 |

| KRAS | p.Gly13Asp | 5 | 4.70% | 5039 | COSM532 |

| LARP4B | p.Thr163HisfsTer47 | 2 | 1.90% | 27 | COSM1638669; COSM4968611 |

| MVK | p.Ala141ArgfsTer18 | 2 | 1.90% | 17 | COSM1241457 |

| PIK3CA | p.His1047Arg | 4 | 3.70% | 2115 | COSM775 |

| PGM5 | p.Ile98Val | 3 | 2.80% | 47 | COSM1109610 |

| RHOA | p. Arg5Gln/Trp | 3 | 2.80% | 23 | COSM446704; COSM190569; COSM4770224; COSM4770223 |

| RHOA | p.Thr37Ala/Ile | 2 | 1.90% | 3 | COSM5064959; COSM1223700 |

| RHOA | p.Tyr42Cys | 2 | 1.90% | 22 | COSM2849892; COSM4770225 |

| TP53 | p.Arg248Trp | 2 | 1.90% | 56 | COSM144150 |

| TP53 | p.Arg342Ter | 2 | 1.90% | 151 | COSM11073 |

| TP53 | p.Cys275Tyr | 2 | 1.90% | 62 | COSM10893 |

| TP53 | p.Val173Leu | 2 | 1.90% | 65 | COSM43559 |

| ZBTB20 | p.Pro619LeufsTer43 | 5 | 4.70% | 26 | COSM267785 |

aRecurrent mutations observed in at least two samples.

Figure 1. Summary of somatic mutations in 107 gastric cancer samples according to molecular subtype.

Genetic alterations of the RTK/RAS/MAPK or/and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways were detected in 34.6% of GC cases (37 individual cases) (Figure 2). Receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) genomic alterations including ERBB2 (n=13), EGFR (n=5), FGFR2 (n=3) and KDR (n=4) were detected in 20.5% of GC cases (n=22). Thirteen samples (12.2% of GC) harbored ERBB2 alterations, 8 contained somatic base substitutions and 5 harbored amplifications, with these events being mutually exclusive. Genetic alterations of PTEN (n=4), PIK3CA (n=11), KRAS (n=11), BRAF (n=3) and MTOR (n=6) were detected in 25.2% of GC cases (n=27). Ten cases (9.4%) harbored mutated PIK3CA and KRAS G13D co-existed in 4 cases (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Therapeutic implications of somatic genomic alterations in 107 clinical gastric cancer cases.

Molecular subtype classification and clinical phenotype

We classified molecular subtypes using genomic data according to subtypes derived by TCGA and correlated clinical covariates of 107 GC patients with those molecular subtypes (Table 4). The EBV subtype (6.5% of GC) was significantly enriched in EBV burden and characterized as uncommon histological subtype (Table 5). In the EBV subtype, no samples with a TP53 mutation were detected, but mutations of ARID1A (4 cases, 57.1%), CDH1 (3 cases, 42.9%), PIK3CA (2 cases, 28.6%) and RHOA (2 cases, 28.6%) were present with a relatively high frequency. Genetic alterations of the JAK2 and PDCD1LG2 genes were not detected in the EBV subgroup. Only one case harbored the mutant CD274 (Figure 1 & Table 4).

Table 4. Somatic mutations in each subtype.

| Somatic mutations | EBV (N=7) | MSI (N=19) | CIN (N=46) | GS (N=35) | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | (%) | Cases | (%) | Cases | (%) | Cases | (%) | ||

| TP53 | 0 | 0.0% | 5 | 26.3% | 26 | 56.5% | 10 | 28.6% | 0.003a |

| ACVR1B | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 5.3% | 1 | 2.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 0.534 |

| ALK | 0 | 0.0% | 3 | 15.8% | 2 | 4.3% | 1 | 2.9% | 0.232 |

| APC | 2 | 28.6% | 1 | 5.3% | 8 | 17.4% | 1 | 2.9% | 0.050 |

| ARID1A | 4 | 57.1% | 14 | 73.7% | 12 | 26.1% | 9 | 25.7% | 0.000a |

| BCOR | 1 | 14.3% | 9 | 47.4% | 2 | 4.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 0.016a |

| BRAF | 0 | 0.0% | 3 | 15.8% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0.003a |

| CBWD1 | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 2.2% | 1 | 2.9% | 1.000 |

| CCND1 | 0 | 0.0% | 3 | 15.8% | 2 | 4.3% | 2 | 5.7% | 0.323 |

| CD274 | 1 | 14.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0.065 |

| CDH1 | 3 | 42.9% | 1 | 5.3% | 3 | 6.5% | 4 | 11.4% | 0.052 |

| CIC | 0 | 0.0% | 5 | 26.3% | 3 | 6.5% | 2 | 5.7% | 0.082 |

| CR1 | 0 | 0.0% | 5 | 26.3% | 2 | 4.3% | 8 | 22.9% | 0.220 |

| CTNNB1 | 1 | 14.3% | 2 | 10.5% | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 5.7% | 0.054 |

| EGFR | 0 | 0.0% | 4 | 21.1% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 2.9% | 0.005a |

| ERBB2 | 0 | 0.0% | 5 | 26.3% | 2 | 4.3% | 1 | 2.9% | 0.028a |

| ERBB3 | 0 | 0.0% | 5 | 26.3% | 2 | 4.3% | 2 | 5.7% | 0.049a |

| FBXW7 | 0 | 0.0% | 3 | 15.8% | 3 | 6.5% | 1 | 2.9% | 0.301 |

| FGFR2 | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 10.5% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0.057 |

| HLA-B | 0 | 0.0% | 3 | 15.8% | 2 | 4.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 0.088 |

| IRF2 | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 10.5% | 1 | 2.2% | 1 | 2.9% | 0.429 |

| JAK2 | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 5.3% | 1 | 2.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 0.534 |

| KDR | 0 | 0.0% | 3 | 15.8% | 1 | 2.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 0.046a |

| KRAS | 0 | 0.0% | 5 | 26.3% | 1 | 2.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 0.002a |

| LARP4B | 0 | 0.0% | 3 | 15.8% | 1 | 2.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 0.046a |

| MDM2 | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 5.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0.243 |

| MEDAG | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 10.5% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0.057 |

| MLH1 | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 10.5% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0.057 |

| MSH2 | 0 | 0.0% | 4 | 21.1% | 1 | 2.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 0.009a |

| MTOR | 0 | 0.0% | 3 | 15.8% | 3 | 6.5% | 0 | 0.0% | 0.111 |

| MVK | 0 | 0.0% | 4 | 21.1% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0.002a |

| MYC | 1 | 14.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0.065 |

| PGM5 | 1 | 14.3% | 4 | 21.1% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0.001a |

| PIK3CA | 2 | 28.6% | 7 | 36.8% | 1 | 2.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 0.000a |

| PTEN | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 10.5% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 2.9% | 0.096 |

| RHOA | 2 | 28.6% | 1 | 5.3% | 2 | 4.3% | 4 | 11.4% | 0.139 |

| SMAD4 | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 5.3% | 1 | 2.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 0.534 |

| STK11 | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 5.3% | 1 | 2.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 0.534 |

| ZBTB20 | 0 | 0.0% | 5 | 26.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0.000a |

| Mutation rate | 2.6 | 6.6 | 1.8 | 1.5 | |||||

ap value less than 0.05.

Abbreviations: CIN, chromosomal instability, EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; GS, genomically stable; MSI, microsatellite instability. Fisher`s exact test was performed to evaluate differences in the respective proportions of somatic mutations between subgroups.

Table 5. Patient characteristics according to molecular subtype.

| EBV (n=7) | MSI (n=19) | CIN (n=46) | GS (n=35) | P value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | (%) | Cases | (%) | Cases | (%) | Cases | (%) | ||

| Age | |||||||||

| ≤50 | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 5.3% | 3 | 6.5% | 6 | 17.1% | 0.580 |

| 51 ∼60 | 2 | 28.6% | 1 | 5.3% | 9 | 19.6% | 6 | 17.1% | |

| 61 ∼70 | 1 | 14.3% | 3 | 15.8% | 13 | 28.3% | 8 | 22.9% | |

| 71 ∼ 80 | 3 | 42.9% | 12 | 63.2% | 16 | 34.8% | 13 | 37.1% | |

| >80 | 1 | 14.3% | 2 | 10.5% | 5 | 10.9% | 2 | 5.7% | |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Female | 1 | 14.3% | 8 | 42.1% | 16 | 34.8% | 11 | 31.4% | 0.660 |

| Male | 6 | 85.7% | 11 | 57.9% | 30 | 65.2% | 24 | 68.6% | |

| Lauren Class | |||||||||

| Diffuse | 3 | 42.9% | 2 | 10.5% | 9 | 19.6% | 14 | 40.0% | 0.069 |

| Intestinal | 2 | 28.6% | 15 | 78.9% | 26 | 56.5% | 15 | 42.9% | |

| Mixed | 2 | 28.6% | 2 | 10.5% | 11 | 23.9% | 6 | 17.1% | |

| WHO Class | |||||||||

| Tubular | 2 | 28.6% | 17 | 89.5% | 32 | 69.6% | 18 | 51.4% | 0.000 |

| Mucinous | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 4.3% | 1 | 2.9% | |

| Poorly cohesive | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 5 | 10.9% | 9 | 25.7% | |

| Mixed | 1 | 14.3% | 1 | 5.3% | 7 | 15.2% | 7 | 20.0% | |

| Uncommon | 4 | 57.1% | 1 | 5.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| pT stages | |||||||||

| T1a/ T1b | 2 | 28.6% | 2 | 10.5% | 10 | 21.7% | 10 | 28.6% | 0.778 |

| T2 | 1 | 14.3% | 3 | 15.8% | 4 | 8.7% | 3 | 8.6% | |

| T3 | 1 | 14.3% | 9 | 47.4% | 17 | 37.0% | 11 | 31.4% | |

| T4a/ T4b | 3 | 42.9% | 5 | 26.3% | 15 | 32.6% | 11 | 31.4% | |

| p N stages | |||||||||

| N0 | 3 | 42.9% | 10 | 52.6% | 16 | 34.8% | 11 | 31.4% | 0.802 |

| N1 | 1 | 14.3% | 3 | 15.8% | 7 | 15.2% | 5 | 14.3% | |

| N2 | 1 | 14.3% | 4 | 21.1% | 9 | 19.6% | 6 | 17.1% | |

| N3 | 2 | 28.6% | 2 | 10.5% | 14 | 30.4% | 13 | 37.1% | |

| M stages | |||||||||

| M0 | 6 | 85.7% | 19 | 100.0% | 43 | 93.5% | 34 | 97.1% | 0.351 |

| M1 | 1 | 14.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 3 | 6.5% | 1 | 2.9% | |

| AJCC Stages | |||||||||

| Stages IA/IB | 3 | 42.9% | 4 | 21.1% | 11 | 23.9% | 11 | 31.4% | 0.605 |

| Stages IIA/IIB | 1 | 14.3% | 9 | 47.4% | 13 | 28.3% | 3 | 8.6% | |

| Stages IIIA/IIIB/IIIC | 2 | 28.6% | 6 | 31.6% | 19 | 41.3% | 20 | 57.1% | |

| Stage IV | 1 | 14.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 3 | 6.5% | 1 | 2.9% | |

| Anatomical regions | |||||||||

| Antrum | 1 | 14.3% | 15 | 78.9% | 25 | 54.3% | 13 | 37.1% | 0.004 |

| Antrum_Body | 1 | 14.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 4.3% | 2 | 5.7% | |

| Fundus_Body | 4 | 57.1% | 4 | 21.1% | 10 | 21.7% | 18 | 51.4% | |

| GEJ_Cardia | 1 | 14.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 7 | 15.2% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| Diffuse | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 2.9% | |

| Pylorus | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 4.3% | 1 | 2.9% | |

| Lymphatic invasion | |||||||||

| Positive | 4 | 57.1% | 17 | 89.5% | 34 | 73.9% | 21 | 60.0% | 0.125 |

| Negative | 3 | 42.9% | 2 | 10.5% | 12 | 26.1% | 13 | 37.1% | |

| Missing | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 2.9% | |

| Venous invasion | |||||||||

| Positive | 2 | 28.6% | 1 | 5.3% | 7 | 15.2% | 5 | 14.3% | 0.416 |

| Negative | 5 | 71.4% | 18 | 94.7% | 39 | 84.8% | 29 | 82.9% | |

| Missing | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 2.9% | |

| Perineural invasion | |||||||||

| Positive | 4 | 57.1% | 6 | 31.6% | 25 | 54.3% | 17 | 48.6% | 0.391 |

| Negative | 3 | 42.9% | 13 | 68.4% | 21 | 45.7% | 17 | 48.6% | |

| Missing | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 2.9% | |

| H. pylori infection | |||||||||

| Negative | 3 | 42.9% | 8 | 42.1% | 21 | 45.7% | 9 | 25.7% | 0.290 |

| Positive | 4 | 57.1% | 11 | 57.9% | 25 | 54.3% | 26 | 74.3% | |

Abbreviations: CIN, chromosomal instability, EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; GS, genomically stable; gastric cancer, GC; GEJ, gastroesophageal junction; H. pylori, Helicobacter pylori; MSI, microsatellite instability; Mixed, mixed type with tubular and poorly cohesive; pT stage, pathological assessment of the primary tumor; pN stage, pathological assessment of the regional lymph nodes; Uncommon, uncommon histologic variants.

The MSI subtype (17.8% of GC) showed instability in one more locus in the MSI assay. The MSI subtype presented with an elevated mutation rate (6.6 per case) and was characterized by alterations of genes involved in mismatch repair. Almost all cases with mutations in MLH1 (n=2/2) and MSH2 (n=4/5) were included in the MSI subtype. Mutations of ARID1A (73.7%), BCOR (47.4%), BRAF (15.8%), EGFR (21.1%), ERBB2 (26.3%), ERBB3 (26.3%), KDR (15.8%), KRAS (26.3%), LARP4B (15.8%), MSH2 (21.1%), MVK (21.1%), PGM5 (21.1%), PIK3CA (36.8%) and ZBTB20 (26.3%) were observed with statistical significance. Interestingly, we observed that mutations of ZBTB20 were limited to the MSI group (Table 4).

The CIN subtype (43.0% of GC) was also characterized by a relatively low-somatic mutation rate (1.8 per case) and a high frequency of TP53 mutations. In the CIN subtype, we observed amplifications of CCND1, CCNE1, ERBB2, FGFR2, KRAS, MYC, PIK3CA and JAK2, and a deletion of PTEN among the 43 genes included in the Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) panel. Ten cases (21.7% in the CIN subtype) harbored CNVs of genes belonging to the RTK/RAS/MAPK and PI3K/PTEN/AKT pathways (Figure 2). CNV detection using a targeted NGS panel of 43 genes represented 30.4 % of the CIN subtype (n=14/46) (Figure 1).

The GS subtype (32.7 % of GC) was characterized by a lack of EBV infection, MSI and somatic CNAs. The GS subtype showed the lowest mutation rate (1.5 per case) (Table 4).

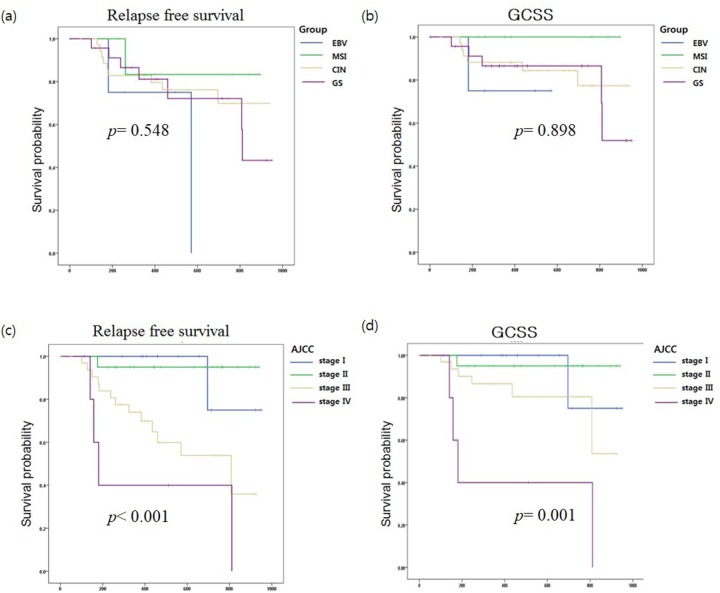

Prognosis analysis in 107 gastric cancer patients

Among the 107 GC patients, the date of last follow-up (months), loco-regional recurrence, distant metastasis, and cause of death were obtained from 72 patients. The median follow up period was 459.5 days, and there were 19 (26.4%) and 12 (16.7%) cases of gastric cancer relapse and gastric cancer-related death, respectively. We conducted a survival analysis but did not observe a substantial difference in overall survival (p= 0.898) or relapse-free survival (RFS, p=0.548) among the four GC subtypes (Figure 3 (a) & (b)). The classification based on AJCC stages showed significant differences in overall survival (p= 0.001) or RFS (p <0.001) (Figures 3 (c) & (d)). Multivariate analysis showed mutant MTOR gene (hazard ratio [HR]:9.26, p= 0.002, 95% CI: 2.22 – 38.58), AJCC stages III (HR: 1.9, p= 0.013, 95% CI: 1.14 - 3.16), AJCC stages IV (HR: 2.15, p= 0.000, 95% CI: 1.40 - 3.30) and mutant CCND1 gene (HR: 5.71, p= 0.028, 95% CI: 1.21 – 27.0) were associated with the relapse of GC.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier (a) relapse-free survival (RFS) and (b) gastric cancer-specific survival (GCSS) curves were stratified by molecular subtypes of gastric cancer (EBV, MSI, CIN, and GS). Kaplan-Meier (c) RFS and (d) GCSS curves were analyzed by AJCC stage.

DISCUSSION

We analyzed germline mutations with paired non-tumor and GC tissue samples in 107 Korean patients. Two cases harbored a likely pathogenic variant (NM_004360.4: c. 2494 G>A, p.V832M) in the CDH1 gene. A V832M mutation has been identified in a hereditary diffuse gastric cancer (HDGC) in a Japanese family. The probands were diagnosed at the age of 56 [21]. This mutation were functionally characterized as a pathogenic mutation [22] and it was also detected in familial lobular breast cancer patients with the wild type BRCA1/2 gene [23]. Two cases with V832M were diagnosed at age 66 and 75, in this study, respectively. Both cases were advanced GC in stage IIB at diagnosis and the family history of GC was not known.

According to the results of somatic variants, the Q1334del/dup (n=23/52) in ARID1A and L15del (n=6/13) in CDH1 were detected at a frequency of 5∼33% of altered alleles in tumor tissue (Table 3 & Supplementary 2). The in-frame indel (Q1334del/dup), which increases the amount of the ARID1A protein in the nucleus and restores its tumor suppressor functions, has also been reported in GC samples [24]. This single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) were also occasionally reported in COSMIC database (COSMIC v78) and pancreatic cancers [25]. A three-nucleotide deletion c.44_46del TGC (L15del) in exon 1 of CDH1, which is in the signal peptide region of the E-cadherin protein, was also identified in Chinese GC patients, whereas it was not detected in 240 controls [26] and endometrial carcinomas [27]. RHOA belongs to the Rho family, which functions in the regulation of the actin cytoskeleton, and functional evidence indicates that mutant RHOA works in a gain-of-function manner in this gene [28]. An RHOA mutation was observed in 8.4% of GC cases (n=9/107), with mutations in the Arg5, Gly17, Thr37, Tyr42 and Glu64 residues (Table 3 & Supplementary 2). Among these mutations, the Arg5, Gly17, and Tyr42 residues are recurrently detected in GC [28, 29].

EBV-infected GC constitutes 5-10% of all GC cases [9, 10] and the Cancer Genome Atlas project demonstrated that EBV-infected GC is one of four molecular subtypes [28]. We also demonstrated that EBV-infected GC grouped as a molecular subtype. As in the EBV-subtype, ARID1A mutations (4 cases, 57.1%) were prevalent, and no samples with a TP53 were detected. The frequency of ARID1A and TP53 mutations were similar to the TCGA data [28]. Inhibitors of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, JAK2 pathway and PD-1/PD-L1, PD-L2 pathway are considered as potentially applicable targeted therapies in EBV-infected GC [4, 30]. However, only 28.6 % of EBV-infected GC harbored PIK3CA mutations (n=2/7), and drug related amplifications of JAK2, CD274, PDCD1LG2 and ERBB2 were not detected in the EBV subtype (Figure 2). To provide applicable therapeutic options, the genetic alterations of PIK3CA AK2, CD274, PDCD1LG2 and ERBB2 should be further validated with large-scale EBV-infected GC.

We observed that the MSI subtype was associated with hyper-mutations in genes and was characterized by a more favorable prognosis than other molecular subtypes. Both the TCGA and ACRG classifications also characterized the MSI subtype by the high mutation frequency and best prognosis [6, 28]. For intestinal type GC, patients with a good prognosis were characterized by a high mutation rate and microsatellite instability. Further, mutations of PIK3CA (29.4%) and KRAS (26.5%) were represented in good prognosis subgroup [31]. In our study, mutations of KRAS (26.3%) and PIK3CA (36.8%) were present with statistical significance in the MSI subtype, and KRAS G13D (4 cases) and PIK3CA H1047R mutations (3 cases) were frequently observed (Table 2). In addition, PIK3CA H1047R mutations were also frequently detected in the MSI subtype in a previous study [6]. The genetic alteration of ZBTB20 (P619fs*43, n=5) was limited to the MSI group. This SNP (P619fs*43; rs758277701; COSM267785) also was limited to the MSI group and similar trend was observed (20% of MSI) in TCGA data [28]. The clinical significance of this variation should be evaluated through further studies.

The distribution of four GC subgroups based on the TCGA [28] and our data were similar (EBV, 8.8% vs. 6.5%; MSI, 21.7% vs. 17.8%; GS, 19.7% vs. 32.7 %; CIN, 49.8 % vs. 43.0 %). Furthermore, the proportion of EBV (6.4% vs. 6.5%), MSI (9.2% vs. 17.8%) and CIN subtype (51 % vs. 43.0 %) in Korean GC were also similar to our data. [32, 33].

Genetic alterations of the RTK/RAS/MAPK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways were detected in 34.6% of GC cases (n=37) (Figure 2). Thirteen samples (12.2% of GC) harbored ERBB2 alterations, 8 contained somatic base substitutions and 5 harbored amplifications, with these events being mutually exclusive. S310F (two cases) and V842I substitutions (two cases) in ERBB2 were recurrently detected in this study and have been functionally characterized as activating and sensitive to lapatinib in ERBB2-negative breast cancers. The functions of ERBB2 R678Q, which was also recurrently detected in this study, related to anti-ERBB2 (HER2)-targeted therapy has not been tested [34]. Ten cases (9.4%) harbored mutated PIK3CA, and KRAS G13D co-existed in 4 cases (Figure 2). Effects of the co-existence of genetic alterations of PIK3CA and KRAS on response to therapy are yet to be evaluated [4]. Dual PI3K and STAT3 blockade using NVP-BKM120 and AG490 (STAT3 inhibitor) showed a synergistic effect in GC cells harboring mutated KRAS by inducing apoptosis [35].

These biomarkers may facilitate enrollment of GC patients into clinical trials evaluating targeted therapies and provide the basis for developing solid therapeutic approaches in Korean GC patients [36–38].

Molecular classification based on four GC subtypes showed no significant survival differences in overall survival (p= 0.898) or RFS (p=0.548) in this dataset. And, ACRG classification-based subtypes also showed no significant association with survival in Korean GC [33]. Therefore, we thought that predicting prognosis for Korea GC patients might be performed more simply and effectively using AJCC stage [39] rather than molecular classification.

We classified molecular subtypes of gastric cancer according to the TCGA system using a targeted NGS panel of 43 genes, EBV, MSI, H. pylori and SNP array. The 43 gene cancer panel consisted of significantly mutated genes from the TCGA and ACRG cohort [6, 28, 40], genes associated with new targeted therapy of GC (EGFR, ERBB2, FGFR2, and KDR) and hereditary cancer syndromes (CDH1, MSH2, MLH1, STK11, and TP53) [12]. We demonstrated 1) the distribution of GC subtypes according to TCGA molecular group, 2) heritable genetic alterations, 3) environmental factors (EBV and H. pylori), 4) somatic genetic aberrant profiles including driver mutations and drug-targeted genetic alterations, and 5) histopathological features in Korean GC patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subject selection

We obtained a total of 107 gastric tumors and matched non-tumor tissue samples from Yonsei University Wonju Medical Center Biobank (n=138, 69 paired samples) and Samkwang Medical Laboratory Biobank (n= 76, 38 paired samples). Tumor samples were obtained from patients who had not received prior chemotherapy or radiotherapy. The gastric cancer tissues consisted of 69 fresh-frozen (FF) paired tumor and non-tumor tissue samples and 38 formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) paired tumor and non-tumor tissue samples. Clinical data, including age, sex, clinical follow-up data, and pathologic reports, were provided from the tissue source institutions. The histologic classification of gastric carcinoma has previously been based on Lauren’s criteria [2] and the 2010 WHO classification system [3]. Tumor TNM stage assignment was evaluated for consistency with the 7th Edition of the TNM classification by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) [39]. Pathologic findings were reviewed by experienced gastrointestinal pathologists (S.N.K. and M.C.). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Samkwang Medical Laboratories and Yonsei University Wonju College of Medicine.

DNA preparation

DNA was extracted from FFPE tumor and adjacent non-tumor gastric tissues using a QIAamp DNA extraction kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. H&E-stained sections from FFPE blocks were reviewed by a board-certified pathologist, and representative sections with tumor content or benign tissue were identified. A G-DEX genomic DNA extraction kit (Intron Biotechnology, Korea) was used for FF tumor and matched non-tumor FF tissues according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The quality and concentration of genomic DNA (gDNA) was evaluated by Nanodrop (ND-1000; Thermo Scientific, DE, USA) and the Agilent 2200 Tape Station system (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA) with Genomic DNA Screen Tape according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The DNA Integrity Number (DIN) for determining the integrity of gDNA was calculated from the electrophoretic trace on the 2200 Tape Station system according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The average value (range) of total DNA concentration in FFPE tissue and FF tissue was 322.7 (12.6 ∼ 322.9) ng/uL and 952.8 (76.0 ∼ 3756.0) ng/uL, respectively. The average value (range) of DIN in FFPE tissue and FF tissue was 2.9 (1.5 ∼ 6.4) and 5.6 (1.4 ∼ 8.4), respectively.

Detection of EBV and H. pylori infection

EBV infection was detected using the Real-Q EBV quantification kit (Biosewoom, Seoul, Korea) and CFX96 real-time PCR system (Bio-Rad, USA) following the manufacturer’s recommendations.

H. pylori infection was detected using Giemsa stain (n=93) or PCR amplification and sequencing (n=14). Primers for PCR and sequencing were derived from a known sequence of the 23S rRNA gene (GenBank Accession No. U27270), as previously described (sense, 5'-CGT AAC TAT AACGGT CCT AAG-3', positions 2365 to 2385; antisense, 5'-TTA GCT AAC AGA AAC ATC AAG-3', positions 2635 to 2653) [41].

Configuration of a gastric cancer-related target gene panel for Korean gastric cancer patients

The cancer panel consisted of genes based on the Mutation Analysis (MutSig 2CV v3.1) results of the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) project (http://gdac.broadinstitute.org/runs/analyses_latest/reports/cancer/STAD-TP/index.html, accessed at 2015.03.30) [28, 40] and significantly mutated genes in the Asian Cancer Research Group (ACRG) cohort and SMC-2 cohort in primary gastric cancer tissues [6]. Genes associated with new targeted therapy of GC (EGFR, ERBB2, FGFR2, and VEGFR2 (KDR)) and hereditary cancer syndromes (CDH1, MSH2, MLH1, STK11, and TP53) were also included in the cancer panel [12].

The entire length of the ROI of the NGS panel of 43 genes was 124,132 bp. To validate the performance of the NGS panel of 43 genes, NA12878 reference materials were used 7 times in 3 batches. The panel average coverage is 1,710× with 97% of targeted bases covered >20×. We downloaded the VCF file for NA12878 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/variation/tools/get-rm/) and then compared it to 7 variant call sets of our control reference materials (NA12878). The sensitivity and specificity of the 43 gene cancer panel were 96.4 % (95% CI: 0.941 – 0.979) and 100%, respectively.

Targeted sequencing and data analysis

DNA fragments of matched tumor and non-tumor tissues were enriched by solution-based hybridization capture, followed by sequencing with the Illumina Hiseq2500 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) with the 2 × 125 bp paired-end read module. gDNA was sheared using an Adaptive Focused Acoustics (AFA)™ with the Covaris Focused-ultrasonicator (Covaris, Inc., Woburn, MA, USA). The quality and quantity of sheared DNA were assessed using the Agilent 2200 Tape Station system with Agilent D1000 ScreenTape (Agilent Technologies, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Capture probes for the coding exons of 43 genes (Supplementary 1)were generated by Celemics (Seoul, Korea). Purification and clean-up of samples were performed using a DynaMag™-50 Magnet (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) with Agencourt® AMPure® XP Kit (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). NGS library amplification was performed using a KAPA Library Amplification Kit (Kapa Biosystems, Inc., Wilmington, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Library preparation, hybridization, capture procedure, and sequencing on the Illumina HiSeq2500 genome analyzer were performed by Celemics according to the protocols recommended by the Celemics User Manual Ver 2.1 (http://www.celemics.com/home/).

The generated reads were trimmed and filtered by Trimmomatic [42] and then mapped against the UCSC hg19 Genome Reference Consortium Human Reference 37 (GRCh37) (http://genome.ucsc.edu/) using the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA) [43]. Picard (http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/), SAMTools [44], and Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK, https://www.broadinstitute.org/gatk/) [45] were used for post-processing alignments, base quality score recalibration, and short insertion/deletion (indel) realignment. After variant calling, variants were added to the annotation using ANNOVAR (http://www.openbioinformatics.org/annovar/)[46] and Variant Effect Predictor (VEP, http://asia.ensembl.org/info/docs/tools/vep/index.html). We used Varscan 2 (http://varscan.sourceforge.net) [47] for the detection of somatic SNVs and indels.

All acquired candidate variations went through post filters recommended by the authors of these tools. We extracted somatic mutations with Varscan2 and post-filtered with downstream analysis for altered allele frequency in tumors > 5%, > 50 x coverage, exonic variants, and population frequency 0.005 less than in the 1000 Genome Project (http://www.1000genomes.org), ESP6500 (http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/), and Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC, http://exac.broadinstitute.org/). We excluded somatic variants detected >2 times in non-tumor tissue. We identified germline variations post-filtered with downstream analysis for altered allele frequency > 30%, > 50x coverage, and population frequency less than 0.01 in the 1000 Genome Project, ESP6500, and ExAC databases. These variants were present in both GC and matched non-tumor" tissue. Visual inspection of filtered calls was performed using Integrated Genomics Viewer 2.3 software (IGV; Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA, USA).

CNV analysis

CNV analysis of the NGS panel of 43 genes was performed with dispersion and the Hidden Markov Model (HMM) method with normalized counts in NextGENe v2.4.1.2 - CNV tool (Softgenetics, State College, PA, USA). The dispersion value was automatically calculated and an HMM was used to merge multiple-exon calls and apply a priori probability. Using the coverage ratio value and the amount of noise in each region, the copy number state of each region in the sample was reported (duplication/normal/deletion) [48]. The NextGENe Viewer (SoftGenetics) was used to visualize the several large CNV calls. To validate the performance of this tool, we compared its results to Her2 immunohistochemistry (IHC) results. Fifty-four cases performed with Her2 IHC consisted of 4 positive cases (score: 3+) and 39 negative cases. We compared the Her2 IHC results and the CNV results from NextGENe-CNV analysis. The sensitivity and specificity of CNV analysis were 75.0% (95% CI: 0.194 – 0.993) and 100% (95% CI: 0.929 – 1.0), respectively.

The Infinium® Global Screening Array (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) was performed for 69 FF tumor tissues and 22 FFPE tumor tissues according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The hybridized arrays were scanned using the HiScan system (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). CNA analysis from single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) based arrays were performed using GISTIC 2.0. [49]. To eliminate bias from copy number variable regions in healthy individuals, we analyzed CNV in a certain range, including somatic CAN-reported regions in GCs (http://www.cbioportal.org/) and dosage-sensitive regions of the genome [50].

Microsatellite instability (MSI) assay

Microsatellite status was assessed by the mononucleotide repeat markers BAT-25, BAT-26, NR-21, NR-24, and NR-27 in tumor and corresponding non-tumor tissues [51]. The five markers were co-amplified in multiplex PCRs performed with Solg2X multiplex PCR Smart mix following the manufacturer’s recommendations. The amplified PCR products were analyzed using the ABI 3500Dx system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and GeneMarker software (SoftGenetics, PA, USA). Tumors with two or more of the five markers showing instability were judged as high-frequency MSI (MSI-H), and tumors showing instability in only one locus were classified as low-frequency MSI (MSI-L) [52].

Molecular subtype classification and statistical analysis

As with the TCGA classification sequence [5], we also divided GC into EBV, MSI and CIN serially according to the results of EBV, MSI and SNP arrays. The remainder was then classified into the GS subgroup.

Fisher`s exact and Chi-squared tests were performed to evaluate differences in the respective proportion of several factors between subgroups. Patient follow-up periods were calculated as time between date of surgery and date of last follow-up (months). Relapse-free survival (RFS) was assessed based on the absence of loco-regional recurrence, distant metastasis, and death from any cause. GC-specific survival (GCSS) was calculated only for patients who died from any GC-related cause. Kaplan-Meier survival curves with log-rank tests were performed to compare RFS and GCSS according to AJCC stage and molecular subtype. Cox proportional hazard models were performed to assess the influence of prognostic factors on RFS. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 22.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Except for the univariate analysis, a p value less than 0.05 was regarded as significant.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS TABLES

Abbreviations

- AMP

amplification

- CIN

chromosomal instability

- DEL

deletion

- CNV

copy number variations

- EBV

Epstein-Barr virus

- GS

genomically stable

- GC

gastric cancer

- GEJ

gastroesophageal junction

- H. pylori

Helicobacter pylori

- MSI

microsatellite instability

- Mixed

mixed type with tubular and poorly cohesive

- pT stage

pathological assessment of the primary tumor

- pN stage

pathological assessment of the regional lymph nodes

- Uncommon

uncommon histologic variants

- VAF

Variant allele frequency

- VUS

a variant of unknown significance

Author contributions

K.L. contributed to the conception and design of the entire study, selected the eligible patients, and supervised the drafting of the manuscript. Y.K. carried out the molecular genetic studies, participated in EBV assay, MSI assay, the design of gastric cancer-related target gene panel, data analysis and writing of the manuscript. J.K. contributed to the design of the study, sample selection, interpretation of data and contributed to the critical revision of manuscript. S.N.K. and M.C. reviewed the pathologic findings of GC tissues, S.C.O. supported for the NGS data analysis pipeline. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

FUNDING

This study was supported by a grant of the Korean Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (A120030) & this research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (2014R1A1A3053986).

REFERENCES

- 1.Fitzmaurice C, Dicker D, Pain A, Hamavid H, Moradi-Lakeh M, MacIntyre MF, Allen C, Hansen G, Woodbrook R, Wolfe C, Hamadeh RR, Moore A, Werdecker A, et al. The Global Burden of Cancer 2013. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:505–527. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.0735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lauren P. THE TWO HISTOLOGICAL MAIN TYPES OF GASTRIC CARCINOMA: DIFFUSE AND SO-CALLED INTESTINAL-TYPE CARCINOMA. AN ATTEMPT AT A HISTO-CLINICAL CLASSIFICATION. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1965;64:31–49. doi: 10.1111/apm.1965.64.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lauwers GY CF, Graham DY. Gastric carcinoma. In: Bowman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, editors. Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System. Lyon: IARC; 2010. In press. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corso S, Giordano S. How Can Gastric Cancer Molecular Profiling Guide Future Therapies? Trends Mol Med. 2016;22:534–544. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2016.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;513:202–209. doi: 10.1038/nature13480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang J, Yu K, Ye XS, Do IG, Liu S, Gong L, Fu J, Jin JG, Choi MG, Sohn TS, Lee JH, Bae JM, Kim ST, et al. Molecular analysis of gastric cancer identifies subtypes associated with distinct clinical outcomes. Nat Med. doi: 10.1038/nm.3850. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.3850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parsonnet J, Friedman GD, Vandersteen DP, Chang Y, Vogelman JH, Orentreich N, Sibley RK. Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk of gastric carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1127–1131. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110173251603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, Matsumura N, Yamaguchi S, Yamakido M, Taniyama K, Sasaki N, Schlemper RJ. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:784–789. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa001999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fukayama M, Hino R, Uozaki H. Epstein-Barr virus and gastric carcinoma: virus-host interactions leading to carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:1726–1733. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00888.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsunou H, Konishi F, Hori H, Ikeda T, Sasaki K, Hirose Y, Yamamichi N. Characteristics of Epstein-Barr virus-associated gastric carcinoma with lymphoid stroma in Japan. Cancer. 1996;77:1998–2004. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960515)77:10<1998::AID-CNCR6>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fitzgerald RC, Hardwick R, Huntsman D, Carneiro F, Guilford P, Blair V, Chung DC, Norton J, Ragunath K, Van Krieken JH, Dwerryhouse S, Caldas C. Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer: updated consensus guidelines for clinical management and directions for future research. J Med Genet. 2010;47:436–444. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.074237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McLean MH, El-Omar EM. Genetics of gastric cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;11:664–674. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2014.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bray F, Ferlay J, Laversanne M, Brewster DH, Gombe Mbalawa C, Kohler B, Pineros M, Steliarova-Foucher E, Swaminathan R, Antoni S, Soerjomataram I, Forman D. Cancer Incidence in Five Continents: Inclusion criteria, highlights from Volume X and the global status of cancer registration. Int J Cancer. 2015;137:2060–2071. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis PA, Sano T. The difference in gastric cancer between Japan, USA and Europe: what are the facts? what are the suggestions? Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2001;40:77–94. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(00)00131-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Masciari S, Dewanwala A, Stoffel EM, Lauwers GY, Zheng H, Achatz MI, Riegert-Johnson D, Foretova L, Silva EM, Digianni L, Verselis SJ, Schneider K, Li FP, et al. Gastric cancer in individuals with Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Genet Med. 2011;13:651–657. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31821628b6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Lier MG, Wagner A, Mathus-Vliegen EM, Kuipers EJ, Steyerberg EW, van Leerdam ME. High cancer risk in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: a systematic review and surveillance recommendations. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1258–1264; author reply 1265. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hearle N, Schumacher V, Menko FH, Olschwang S, Boardman LA, Gille JJ, Keller JJ, Westerman AM, Scott RJ, Lim W, Trimbath JD, Giardiello FM, Gruber SB, et al. Frequency and spectrum of cancers in the Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:3209–3215. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watson P, Vasen HF, Mecklin JP, Bernstein I, Aarnio M, Jarvinen HJ, Myrhoj T, Sunde L, Wijnen JT, Lynch HT. The risk of extra-colonic, extra-endometrial cancer in the Lynch syndrome. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:444–449. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirota WK, Zuckerman MJ, Adler DG, Davila RE, Egan J, Leighton JA, Qureshi WA, Rajan E, Fanelli R, Wheeler-Harbaugh J, Baron TH, Faigel DO. ASGE guideline: the role of endoscopy in the surveillance of premalignant conditions of the upper GI tract. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:570–580. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N, Velculescu VE, Zhou S, Diaz LA, Jr, Kinzler KW. Cancer genome landscapes. Science. 2013;339:1546–1558. doi: 10.1126/science.1235122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yabuta T, Shinmura K, Tani M, Yamaguchi S, Yoshimura K, Katai H, Nakajima T, Mochiki E, Tsujinaka T, Takami M, Hirose K, Yamaguchi A, Takenoshita S, Yokota J. E-cadherin gene variants in gastric cancer families whose probands are diagnosed with diffuse gastric cancer. Int J Cancer. 2002;101:434–441. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suriano G, Mulholland D, de Wever O, Ferreira P, Mateus AR, Bruyneel E, Nelson CC, Mareel MM, Yokota J, Huntsman D, Seruca R. The intracellular E-cadherin germline mutation V832 M lacks the ability to mediate cell-cell adhesion and to suppress invasion. Oncogene. 2003;22:5716–5719. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schrader KA, Masciari S, Boyd N, Salamanca C, Senz J, Saunders DN, Yorida E, Maines-Bandiera S, Kaurah P, Tung N, Robson ME, Ryan PD, Olopade OI, et al. Germline mutations in CDH1 are infrequent in women with early-onset or familial lobular breast cancers. J Med Genet. 2011;48:64–68. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2010.079814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guan B, Gao M, Wu CH, Wang TL, Shih Ie M. Functional analysis of in-frame indel ARID1A mutations reveals new regulatory mechanisms of its tumor suppressor functions. Neoplasia. 2012;14:986–993. doi: 10.1593/neo.121218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bailey P, Chang DK, Nones K, Johns AL, Patch AM, Gingras MC, Miller DK, Christ AN, Bruxner TJ, Quinn MC, Nourse C, Murtaugh LC, Harliwong I, et al. Genomic analyses identify molecular subtypes of pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2016;531:47–52. doi: 10.1038/nature16965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen QH, Deng W, Li XW, Liu XF, Wang JM, Wang LF, Xiao N, He Q, Wang YP, Fan YM. Novel CDH1 germline mutations identified in Chinese gastric cancer patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:909–916. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i6.909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kandoth C, Schultz N, Cherniack AD, Akbani R, Liu Y, Shen H, Robertson AG, Pashtan I, Shen R, Benz CC, Yau C, Laird PW, Ding L, et al. Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature. 2013;497:67–73. doi: 10.1038/nature12113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kakiuchi M, Nishizawa T, Ueda H, Gotoh K, Tanaka A, Hayashi A, Yamamoto S, Tatsuno K, Katoh H, Watanabe Y, Ichimura T, Ushiku T, Funahashi S, et al. Recurrent gain-of-function mutations of RHOA in diffuse-type gastric carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2014;46:583–587. doi: 10.1038/ng.2984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang K, Yuen ST, Xu J, Lee SP, Yan HH, Shi ST, Siu HC, Deng S, Chu KM, Law S, Chan KH, Chan AS, Tsui WY, et al. Whole-genome sequencing and comprehensive molecular profiling identify new driver mutations in gastric cancer. 2014;46:573–582. doi: 10.1038/ng.2983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacome AA, Lima EM, Kazzi AI, Chaves GF, Mendonca DC, Maciel MM, Santos JS. Epstein-Barr virus-positive gastric cancer: a distinct molecular subtype of the disease? Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2016;49:150–157. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0270-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bria E, Pilotto S, Simbolo M, Fassan M, de Manzoni G, Carbognin L, Sperduti I, Brunelli M, Cataldo I, Tomezzoli A, Mafficini A, Turri G, Karachaliou N, et al. Comprehensive molecular portrait using next generation sequencing of resected intestinal-type gastric cancer patients dichotomized according to prognosis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:22982. doi: 10.1038/srep22982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schumacher SE, Shim BY, Corso G, Ryu MH, Kang YK, Roviello F, Saksena G, Peng S, Shivdasani RA, Bass AJ, Beroukhim R. Somatic copy number alterations in gastric adenocarcinomas among Asian and Western patients. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0176045. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koh J, Ock CY, Won Kim J, Nam SK, Kwak Y, Yun S, Ahn SH, Park DJ, Kim HH, Kim WH, Lee HS. Clinicopathologic implications of immune classification by PD-L1 expression and CD8-positive tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in stage II and III gastric cancer patients. Oncotarget. 2017 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15465. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.15465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bose R, Kavuri SM, Searleman AC, Shen W, Shen D, Koboldt DC, Monsey J, Goel N, Aronson AB, Li S, Ma CX, Ding L, Mardis ER, Ellis MJ. Activating HER2 mutations in HER2 gene amplification negative breast cancer. Cancer Discov. 2013;3:224–237. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park E, Park J, Han SW, Im SA, Kim TY, Oh DY, Bang YJ. NVP-BKM120, a novel PI3K inhibitor, shows synergism with a STAT3 inhibitor in human gastric cancer cells harboring KRAS mutations. Int J Oncol. 2012;40:1259–1266. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2011.1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ali SM, Sanford EM, Klempner SJ, Rubinson DA, Wang K, Palma NA, Chmielecki J, Yelensky R, Palmer GA, Morosini D, Lipson D, Catenacci DV, Braiteh F, et al. Prospective comprehensive genomic profiling of advanced gastric carcinoma cases reveals frequent clinically relevant genomic alterations and new routes for targeted therapies. Oncologist. 2015;20:499–507. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu YJ, Shen D, Yin X, Gavine P, Zhang T, Su X, Zhan P, Xu Y, Lv J, Qian J, Liu C, Sun Y, Qian Z, et al. HER2, MET and FGFR2 oncogenic driver alterations define distinct molecular segments for targeted therapies in gastric carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:1169–1178. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xie L, Su X, Zhang L, Yin X, Tang L, Zhang X, Xu Y, Gao Z, Liu K, Zhou M, Gao B, Shen D, Zhang L, et al. FGFR2 gene amplification in gastric cancer predicts sensitivity to the selective FGFR inhibitor AZD4547. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:2572–2583. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Washington K. 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual: stomach. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:3077–3079. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1362-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lawrence MS, Stojanov P, Polak P, Kryukov GV, Cibulskis K, Sivachenko A, Carter SL, Stewart C, Mermel CH, Roberts SA, Kiezun A, Hammerman PS, McKenna A, et al. Mutational heterogeneity in cancer and the search for new cancer-associated genes. Nature. 2013;499:214–218. doi: 10.1038/nature12213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim JM, Kim JS, Kim N, Kim YJ, Kim IY, Chee YJ, Lee CH, Jung HC. Gene mutations of 23S rRNA associated with clarithromycin resistance in Helicobacter pylori strains isolated from Korean patients. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008;18:1584–1589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lohse M, Bolger AM, Nagel A, Fernie AR, Lunn JE, Stitt M, Usadel B. RobiNA: a user-friendly, integrated software solution for RNA-Seq-based transcriptomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:W622–627. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, Sivachenko A, Cibulskis K, Kernytsky A, Garimella K, Altshuler D, Gabriel S, Daly M, DePristo MA. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20:1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koboldt DC, Zhang Q, Larson DE, Shen D, McLellan MD, Lin L, Miller CA, Mardis ER, Ding L, Wilson RK. VarScan 2: somatic mutation and copy number alteration discovery in cancer by exome sequencing. Genome Res. 2012;22:568–576. doi: 10.1101/gr.129684.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shin S, Kim Y, Oh SC, Yu N, Lee ST, Choi JR, Lee KA. Validation and optimization of the Ion Torrent S5 XL sequencer and Oncomine workflow for BRCA1 and BRCA2 genetic testing. Oncotarget. 2017 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mermel CH, Schumacher SE, Hill B, Meyerson ML, Beroukhim R, Getz G. GISTIC2.0 facilitates sensitive and confident localization of the targets of focal somatic copy-number alteration in human cancers. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R41. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-4-r41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zarrei M, MacDonald JR, Merico D, Scherer SW. A copy number variation map of the human genome. Nat Rev Genet. 2015;16:172–183. doi: 10.1038/nrg3871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Buhard O, Cattaneo F, Wong YF, Yim SF, Friedman E, Flejou JF, Duval A, Hamelin R. Multipopulation analysis of polymorphisms in five mononucleotide repeats used to determine the microsatellite instability status of human tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:241–251. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.7227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boland CR, Thibodeau SN, Hamilton SR, Sidransky D, Eshleman JR, Burt RW, Meltzer SJ, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Fodde R, Ranzani GN, Srivastava S. A National Cancer Institute Workshop on Microsatellite Instability for cancer detection and familial predisposition: development of international criteria for the determination of microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5248–5257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.