Abstract

Introduction

Pregnancy rates after frozen embryo transfer (FET) have improved in recent years and are now approaching or even exceeding those obtained after fresh embryo transfer. This is partly due to improved laboratory techniques, but may also be caused by a more physiological hormonal and endometrial environment in FET cycles. Furthermore, the risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome is practically eliminated in segmentation cycles followed by FET and the use of natural cycles in FETs may be beneficial for the postimplantational conditions of fetal development. However, a freeze-all strategy is not yet implemented as standard care due to limitations of large randomised trials showing a benefit of such a strategy. Thus, there is a need to test the concept against standard care in a randomised controlled design. This study aims to compare ongoing pregnancy and live birth rates between a freeze-all strategy with gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist triggering versus human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) trigger and fresh embryo transfer in a multicentre randomised controlled trial.

Methods and analysis

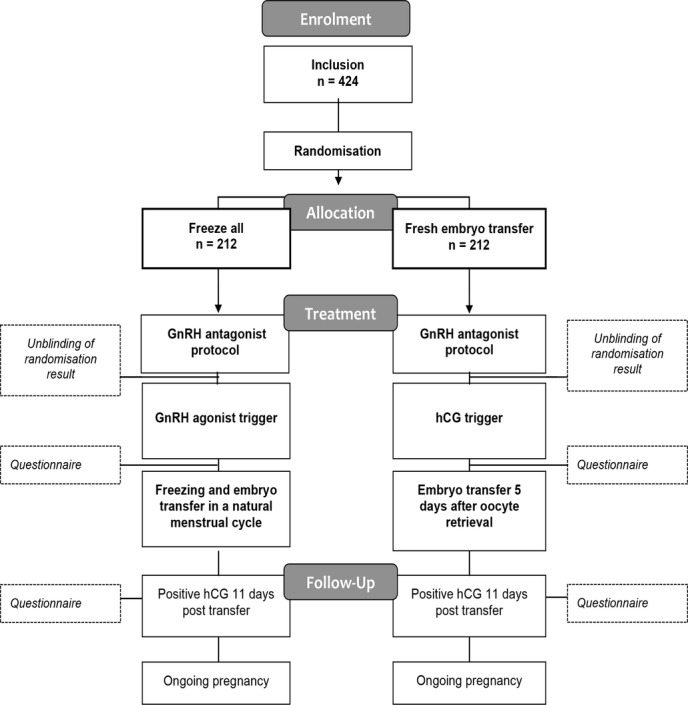

Multicentre randomised, controlled, double-blinded trial of women undergoing assisted reproductive technology treatment including 424 normo-ovulatory women aged 18–39 years from Denmark and Sweden. Participants will be randomised (1:1) to either (1) GnRH agonist trigger and single vitrified-warmed blastocyst transfer in a subsequent hCG triggered natural menstrual cycle or (2) hCG trigger and single blastocyst transfer in the fresh (stimulated) cycle. The primary endpoint is to compare ongoing pregnancy rates per randomised patient in the two treatment groups after the first single blastocyst transfer.

Ethics and dissemination

The study will be performed in accordance with the ethical principles in the Helsinki Declaration. The study is approved by the Scientific Ethical Committees in Denmark and Sweden. The results of the study will be publically disseminated.

Trial registration number

NCT02746562; Pre-results.

Keywords: ART, FET, Freeze-all, RCT, Ongoing pregnancy rate, OPR

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The design: A multicentre, randomised controlled double-blinded trial powered to identify an increase in ongoing pregnancy rate in the freeze-all group compared with the conventional fresh blastocyst transfer group.

The study includes normo-ovulatory women aged 18–39 years with a body mass index <35; thus, results can be extrapolated to the majority of the normo-ovulatory infertile population.

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist trigger in the freeze-all group adds a concept of an ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS)-free strategy.

As both GnRH-agonist trigger and elective freeze-all are new treatment approaches, we will not be able to distinguish the two effects from each other, but compare an OHSS-free strategy with a conventional fresh transfer strategy.

The study is powered to detect a 13% difference in ongoing pregnancy between the two groups; thus, smaller but yet clinically relevant differences may be overlooked.

Introduction

The use of assisted reproductive technology (ART) is increasing and presently up to 5% of birth cohorts in certain countries are conceived by ART.1 In recent years, pregnancy rates following frozen embryo transfer (FET) have rapidly increased and may now be a viable and appropriate alternative to the conventional fresh embryo transfer in ART. The main reason is the introduction of vitrification, increasing post-thawing survival rates after blastocyst culture significantly as compared with previous years.2 3 Implantation as well as clinical and ongoing pregnancy rates are correspondingly improving in frozen cycles and approaching or even exceeding those associated with fresh embryo transfer.4–6

A freeze-all strategy has been suggested as a way to further improve success rates in ART, arguing that the use of the best embryo in frozen cycles instead of in fresh cycles may potentially increase pregnancy rates and live birth rates.6 7 The rationale is that transfer of a frozen-thawed embryo in a subsequent natural menstrual cycle has the advantage of an endometrium that has not been exposed to the supraphysiological levels of estradiol and progesterone following controlled ovarian stimulation (COS) in fresh cycles, which may negatively affect endometrial receptivity.5 8Elective FET (eFET) moreover has the benefit of essentially eliminating the risk of developing late ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) associated with the pregnancy-related rise in human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) levels.9 If ovulation is induced with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist instead of hCG and all embryos are frozen, even early OHSS is minimised making the overall OHSS risk extremely low.10 Freezing and thawing of embryos additionally encourages an elective single embryo transfer policy with cumulative pregnancy rates similar to those seen after double embryo transfer.11 12

Despite evidence suggesting that ART outcomes may be further improved with the adaptation of a freeze-all strategy, the implementation remains a topic of ongoing debate and only one in five transfers in Europe on average was performed with frozen-thawed embryos in 2012.1 In a large recent study, including 1508 patients with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) comparing the freeze-all strategy with conventional fresh embryo transfer, the authors found a significantly higher frequency of live birth after the first FET compared with fresh embryo transfer (49.3% vs 42.0%).7 Correspondingly, in a meta-analysis including three trials accounting for 633 cycles in women aged 27–33 years, eFET resulted in significantly higher clinical and ongoing pregnancy rates compared with fresh embryo transfer.6 However, the included studies showed heterogeneity and one of the included publications was later retracted due to serious methodological flaws. In addition, the vast majority of the participants were high responders (496 out of 633) accounting for a highly selected group of patients, mostly consisting of patients with PCOS or patients with and polycystic ovarian-like morphology.6 Moreover, previous studies were performed in China, the USA and Japan making them less generalisable to a European ART setting. According to Clinicaltrials.gov, there are a few ongoing European randomised controlled trials (RCTs) on the freeze-all strategy; however, none of these studies investigate an almost complete OHSS-free strategy including GnRH-agonist trigger in the freeze-all group.

OHSS is one of the most severe side effects of ART and is potentially life threatening. The present protocol describes a randomised trial assessing a new ART treatment strategy, where OHSS can be almost completely avoided. The results are very important as the majority of our patients could avoid the OHSS risk by applying the ‘GnRH agonist and freeze-all’ strategy, maybe even with a higher chance of pregnancy. This concept has not been assessed before and should relevantly be considered when planning studies investigating the freeze-all strategy underlining the need for large multicentre RCTs exploring the GnRH agonist and freeze-all strategy in a broad population of ART patients. The present study will explore this approach in a bi-national multicentre RCT setting providing information on the prospect of a freeze-all strategy.

Objectives

Primary objective

The primary objective of the study is to investigate if the ongoing pregnancy rate per randomised patient after the first potential single blastocyst transfer is superior in a freeze-all and transfer later strategy compared with the conventional hCG trigger and fresh transfer strategy.

Ongoing pregnancy rate is defined as an intrauterine pregnancy with a fetal heart beat at transvaginal ultrasound in gestational week 7–8.

Ongoing pregnancy rate per first blastocyst transfer is also considered as a primary aim of the study addressing possible differences in endometrial receptivity between the two groups.

Secondary objectives

Secondary objectives include:

To assess cumulative live birth rates after one complete treatment cycle including consecutive single blastocyst transfers of all embryos deriving from that oocyte retrieval (fresh and frozen) in the two study groups;

To assess the transfer cancellation rate in the two study groups;

To assess the prevalence of OHSS in the two study groups;

To compare neonatal outcomes (preterm birth, low birth weight, small-for-gestational age, large-for-gestational age and perinatal mortality) and the incidence of pre-eclampsia in the two study groups;

To measure time-to-pregnancy from the date of start of COS to the date of the first ongoing pregnancy in the two study groups;

To assess quality of life for both female and male partners during the two treatment protocols;

To assess physical well-being by way of questionnaires and VAS scores regarding pain and discomfort at 4 and 16 days after oocyte retrieval in the two study groups.

Methods and analysis

Study design

The study is designed as a multicentre randomised, controlled double-blinded trial with seven fertility clinics in Denmark and Sweden participating. All seven clinics are part of a University Hospital setting and perform standardised treatments according to the public healthcare system in Denmark and Sweden. Patient enrolment started in May 2016 and the last patients are expected to be included in the study in May 2018 with the primary outcome measure, ongoing pregnancy rate, being known for these patients approximately 4 months later for the patients allocated to the freeze-all group.

Study population/participants and recruitment

The study participants will consist of women and their partners initiating ART treatment at one of the seven participating public clinics in Denmark and Sweden. Before initiating treatment, patients will attend an information meeting, where they will be informed about the standard ART procedures, treatment regimens as well as ongoing clinical studies at the treatment sites. Those patients not able to participate in the information meeting will instead be informed by a doctor at an outpatient clinic consultation. Recruitment will be carried out by the doctors and study nurses at the fertility clinics. Prior to the initiation of treatment, patient files will be browsed by investigators at the clinics to assess if the patient fulfils the immediate inclusion criteria. Screening, including ultrasound examination of the uterus and ovaries is done on menstrual cycle day 2 or 3 securing that all inclusion criteria are met. Patients fulfilling the study criteria will start COS using a GnRH antagonist cotreatment in accordance with the standard routines of the trial site.

Eligibility criteria

To participate in the study, women will be required to meet the following inclusion criteria: female age 18–39 years; eligibility to initiate the first, second or third ART cycle with oocyte aspiration (in vitro fertilisation (IVF) or intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI)); Anti-Müllerian Hormone (AMH) level > 6.28 pmol/L (Roche Elecsys assay) corresponding to the AMH threshold level used in the Bologna criteria to characterise poor responders; regular menstrual cycle ≥24 days and ≤35 days: body mass index (BMI) 18–35 kg/m2; preservation of both ovaries and capability of signing informed consent. For specific exclusion criteria, see box 1.

Box 1. Specific exclusion criteria.

Endometriosis stage III to IV

Ovarian cysts with a diameter >30 mm at day of start of stimulation

Submucosal fibroids

Women with severe comorbidity (insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, pulmonary, liver or kidney disease)

Dysregulated thyroid disease

Non-Danish or English speaking

Contraindications or allergies to use of gonadotropins or gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonists

Testicular sperm aspiration

Oocyte donation

Previous inclusion in the study

Randomisation and blinding

Patients who meet the inclusion criteria are randomised 1:1 to one of the two treatment groups: (1) freeze-all including GnRH agonist trigger, blastocyst vitrification and subsequent FET in an hCG-triggered natural cycle or (2) traditional hCG trigger and fresh blastocyst transfer.

The randomisation is carried out by a study nurse or a non-treating doctor using a computerised randomisation programme that runs a minimisation algorithm, initially seeded using a random block sequence for the first subjects. The minimisation algorithm is balancing the following variables: female age (mean and frequency of age ≥37 years), previously performed cycles (frequency of 0/1/2 cycles), nulliparous (frequency of yes/no), fertilisation method (frequency of IVF/ICSI), smoking (frequency of yes/no), AMH (≤12 pmol/L, 13–28 pmol/L, >28 pmol/L) and mean BMI. It selects with high (but less than 1.0) probability the treatment arm that provides the optimal balance between the arms. It also enforces predefined maximum allowed differences in number of subjects in each treatment arm at each study site (fertility clinic) and within the whole study.

Furthermore, the starting dose of follicular-stimulating hormone (FSH) is entered into the randomisation programme before randomisation is performed to make sure that the FSH dose is decided on before randomisation. Both the treating consultants and patients are blinded to the randomisation results during the COS until the day when ovulation trigger is planned.

Treatment arms and interventions

The short GnRH antagonist protocol and blastocyst culture is applied in both treatment arms. The starting dose and type of gonadotropin is decided by the doctor on stimulation day 1 (cycle day 2 or 3) and entered into the randomisation programme prior to randomisation. Individualised gonadotropin dosing based on AMH, age, weight, previous COH cycles are applied. Recombinant FSH (rFSH) or human menopausal gonadotropin (hMG) can be used according to the preference of the site, but the daily dose cannot exceed 300 IU. The gonadotropin stimulation will be performed according to the routine in the clinics and can be changed during the treatment according to the ovarian response to stimulation evaluated through ultrasound examination. GnRH antagonist cotreatment is initiated at a daily dose of 0.25 mg on stimulation day 5 or 6 according to the general standards in each clinic and is continued throughout the rest of the gonadotropin stimulation period.

Ultrasound examination is performed on cycle day 2 or 3 (baseline), stimulation day 6 or 7 and subsequently every second to third day until ovulation trigger is decided according to the hCG/GnRH agonist trigger criterion: as soon as three follicles are ≥17 mm or 1 day later. At baseline, a comprehensive ultrasound examination will estimate endometrial thickness, ovarian volume as well as number and size of antral follicles divided into the following three subclasses: 2–4 mm, 5–7 mm and 8–10 mm. On the day of ovulation trigger, endometrial thickness and morphology as well as follicular development with number and size of follicles>10 mm are registered.

When ovulation trigger is decided, the result of the randomisation is disclosed to both doctors and patients and ovulation and oocyte maturation is triggered with a GnRH agonist trigger injection (0.5 mg buserelin) in the freeze-all group or a single injection of 250 µg of hCG in the fresh embryo transfer group. If >18 follicles with a diameter >11 mm are observed in the fresh embryo transfer group GnRH agonist triggering with buserelin and vitrification of all embryos will be performed to avoid severe OHSS. All fertilised oocytes are cultured to the blastocyst stage and the embryos are scored and ranked according to standardised criteria ascribed to this study. The ranking will assure that the blastocyst with the highest implantation potential is transferred first in both groups. In the fresh transfer group, single blastocyst transfer is performed on day 5 after oocyte retrieval if a good-quality blastocyst has developed. Surplus good quality blastocysts will be vitrified on day 5 or 6. Luteal phase support is administered as vaginal progesterone according to the clinics standard procedures from day 2 after oocyte retrieval until the day of hCG test; thus, luteal support is not extended into early pregnancy. In the freeze-all group, all blastocysts of good quality are vitrified on day 5 or 6 depending on when the blastocyst stage is reached. The blastocyst with the highest rank is marked and will be the first one used in a subsequent hCG-triggered modified natural FET cycle. There should be at least one completed menstrual cycle in between the stimulation and the embryo transfer. In FET cycles, a single injection of 250 µg hCG is administered, when the leading follicle is > 17 mm. Blastocyst transfer is performed 6 or 7 days after the hCG injection. No luteal phase support is given.

A plasma hCG test is performed 11 days after blastocyst transfer. Ongoing clinical pregnancy is defined as fetal heart beat at gestational age 7–8 confirmed by transvaginal ultrasound 3–4 weeks after a positive plasma hCG test. For overview of study design, see figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the freeze-all study design. hCG, human chorionic gonadotropin; GnRH, gonadotropin-releasing hormone.

Data collection and management

Treatment-related data are collected at (1) baseline (cycle day 2 or 3), (2) day of ovulation trigger and (3) 5 days after oocyte retrieval. Data on blastocysts are collected at culture day 5/6. Follow-up data on all pregnancies resulting from blastocysts transferred according to the study protocol will be followed from study inclusion and 1 year onwards. Data are transferred to an online eCRF system called MediCase with an underlying Microsoft SQL server database located in a guarded underground facility in Sweden. Data are backed up daily (one backup to another computer in the same physical location as the server and a second backup to a physically separate location, also in Sweden). MediCase has a complete audit trail and is designed to only contain de-identified data and is entirely based on anonymous subject ID numbers used in the trial.

Sample collection

Blood samples will be collected three times during the treatment process: (1) baseline (cycle day 2 or 3), (2) day of ovulation trigger and (3) 16 days after oocyte retrieval (day of pregnancy test in the fresh embryo transfer group). For overview of samples, see table 1. Furthermore, one serum, plasma and full-blood sample are drawn at baseline and on the day of triggering and stored according to a trial specific laboratory manual in a project-specific biobank as backup for analysis of endocrine and immunological factors of relevance for pregnancy. The frozen samples will be kept anonymised in the biobank with only the patient-specific project ID number and collection date marked on the sample. The samples will be stored in the participating fertility clinics and destroyed 5 years after the end of the study period if not analysed.

Table 1.

Blood sample collection

| Baseline (cycle day 2 or 3) | AMH |

| FSH | |

| LH | |

| Estradiol | |

| Progesterone | |

| TSH | |

| TPO antibodies | |

| Vitamin D | |

| CRP | |

| suPAR* | |

| Day of ovulation induction | FSH |

| LH | |

| Estradiol | |

| Progesterone | |

| CRP | |

| suPAR* | |

| 16 days after oocyte retrieval | CRP |

| suPAR* | |

| hCG† |

*suPAR only measured at Hvidovre Hospital.

†Only fresh embryo transfer group.

AMH, anti-mullerian hormone; CRP, C reactive protein; FSH, follicular-stimulating hormone; hCG, human chorionic gonadotropin; LH, luteinising hormone; suPAR, soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor; TPO, thyroperoxidase; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone.

Further blood samples will be collected during the luteal phase for a smaller subgroup of 60 patients,30 in each treatment group as part of a luteal phase subgroup analysis of differences in hormone levels in the two groups. The following blood samples will be collected at (1) day of ovulation trigger and (2) day of ovulation trigger, day of ovulation trigger +7, +11, +14, +16 and +19: estradiol, inhibin-A, OH-progesterone, progesterone, luteinising hormone and hCG.

Questionnaires

Women as well as male partners will be asked to fill in quality-of-life-validated questionnaires twice during the treatment process: (1) 4 days after oocyte retrieval and (2) 16 days after oocyte retrieval. The questionnaires consist of standardised questions specially developed to explore emotional aspects as well as quality-of-life-related aspects of the treatment process. The women will at the same time be asked to fill in questionnaires regarding physical discomfort including a Visual Analog Scale (VAS) score of physical pain in relation to the treatment.

Statistics

Sample size calculation

The trial is designed as a superiority study. Sample size calculation indicates that 424 participants (n=212 in each arm) are required to have a 80% chance of detecting, at a significance level at 0.05, an increase in the primary outcome measure (ongoing pregnancy rate per randomised patient after the first potential blastocyst transfer) from 30% in the control group (fresh embryo transfer) to 43% in the experimental group (freeze-all).

Outcome measurements (primary and secondary)

The primary endpoint is the ongoing pregnancy rate per randomised patient after the transfer of the first potential blastocyst. Ongoing pregnancy is defined as a pregnancy with a positive fetal heart beat at gestational week 7–8.

Other endpoints explored in the study contribute to the assessment of other relevant aspects of the freeze-all strategy including ongoing pregnancy rates per transfer, per started stimulation and per oocyte pick-up (percentage of participants with an ultrasound confirmation of fetal heart beat at gestational age 7–8) as well as live birth rate and cumulative live birth rates (percentage of participants with one live born neonate after 1 year of follow-up). The study furthermore aims to document the prevalence of OHSS assessed by the number of patients admitted to hospital under this diagnosis and the number of patients having ascites puncture. In addition, it is planned to evaluate pregnancy-related complications as well as neonatal outcomes in both groups. For complete overview of all secondary endpoint measures, see box 2.

Box 2. Secondary endpoints.

Ongoing pregnancy rate per start of per started ovarian stimulation and per oocyte retrieval

Live birth rate after the first blastocyst transfer calculated per randomised patient, per started ovarian stimulation, per oocyte retrieval and per transfer

Cumulative live birth rate after one stimulated cycle with oocyte retrieval

Cumulative live birth rate after use of all frozen blastocyst or after at least 1 year of follow-up

Number of cycles with no embryo transfer

Time-to-pregnancy (from start of ovarian stimulation to positive human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG))

Time-to-delivery

Cancelled embryo transfers

Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome

Preterm birth

Low birth weight

Small-for-gestational age

Large-for-gestational age

Perinatal mortality

Pre-eclampsia

Placental rupture

Positive hCG 11 days post embryo transfer

Miscarriage, biochemical pregnancies, ectopic pregnancies

Quality of life for female and male partner

Cost-effectiveness

Other outcome measurements

Number of good blastocysts

Number of fertilised oocytes

Number of high quality embryos day 2

Number of grade 1 blastocysts

Number of frozen blastocyst

Paraclinical data: endocrine, genetic and immunological parameters

Statistical analyses

Analyses of cumulative pregnancy rates and live birth rates after one oocyte retrieval including fresh and all FET cycles will be compared by Cox-regression analyses. Comparisons between treatment groups will be performed primarily according to the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle but per-protocol analyses will also be done. Continuous data will be compared by students t-test or Mann-Whitney U test and Kruskal-Wallis test as appropriate. Proportions will be compared with χ² test. Predictive factors for ongoing pregnancy in the two treatment groups will be tested with multivariate logistic regression analyses. A p value of <0.5 will be considered as statistically significant.

Patients in fresh embryo transfer group with GnRH agonist triggering

Patients allocated to the fresh transfer group who end up receiving GnRH agonist trigger and vitrification of all blastocysts due to risk of OHSS (>18 follicles with a diameter >11 mm on trigger day) will still be analysed as part of the fresh transfer group according to the ITT principle. Their first blastocyst transfer will derive from their first FET cycle and ongoing pregnancies from these first transfers will be included in the numerator together with ongoing pregnancies derived from the majority of patients with first blastocyst transfer in the fresh cycle. The denominator will be all randomised patients.

Following oral and written information outlining the rationale, trial design, aims and treatment procedures, written informed consent will be obtained from female and male partners prior to the enrolment in the study.

The participants are stimulated using individualised doses of gonadotropin stimulation in accordance with the clinical practice at each site. In all clinics serum, AMH is considered when the FSH dose is determined. All medicines used in the study are part of standard ART care.

The overall safety of the patients is high in both treatment groups. The risk of OHSS is expected to be similar to the standard clinical protocol in the fresh embryo transfer group and lower in the freeze-all group in which GnRH agonist is used for ovulation trigger. In women in the fresh embryo transfer group with a risk of OHSS development (more than 18 follicles with a diameter over 11 mm), GnRH agonist will be used for trigger instead of hCG and all blastocysts will be vitrified and the transfer postponed.

No financial incentive exists for the participants as all couples are reimbursed for their first three ART treatments in the public healthcare system in the Nordic countries.

The results of the study will be publicly disseminated in peer-reviewed scientific journals and presented at relevant international scientific meetings such as ESHRE (European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology) and ASRM (American Society for Reproductive Medicine). In addition, results will be published in popular science journals and other media.

Discussion

The increasing interest in possible benefits of a freeze-all strategy and the limitations of existing RCTs comparing this strategy with conventional fresh embryo transfer underlines the need for additional studies. The few previous RCTs have demonstrated significantly increased pregnancy and delivery rates with freeze-all; however, these studies were performed in highly selected patient populations with poor generalisability.6 7 Further, the treatment strategy combining GnRH agonist trigger and freeze-all minimising the risk of severe OHSS development has not yet been investigated in a RCT setting. As GnRH agonist trigger does not hamper the yield of mature oocytes12 and reduces the risk of OHSS to an absolutely minimum, it seems rational to include GnRH agonist trigger in the freeze-all concept. Evidently, we are unable to distinguish between the effect of the GnRH-agonist trigger and the effect of elective freeze-all, when both are included in the freeze-all treatment arm. The present study therefore compares an ‘OHSS-free’ freeze-all strategy including GnRH agonist trigger with a fresh transfer strategy with hCG trigger. In both treatment arms individualised gonadotropin dosing is used with the possibility of conversion to GnRH agonist trigger and segmentation in case of risk of OHSS development in the fresh embryo transfer group. Individualised gonadotropin dosing based on female age and weight, antral follicle count, AMH and results of previous COH cycles is applied, as this is the standard treatment approach used routinely in all of the participating clinics. The AMH cut-off value at 6.28 pmol/L (Roche Elecsys assay) corresponding to the Bologna criteria for poor ovarian response was chosen to have a reasonable chance of the patient ending up with at least one usable blastocyst after aspiration. It could be argued that an open randomisation, rather than a double-blinded study design, would allow a better exploration of the concept as higher gonadotropin doses and more oocytes could be safely aimed for in the freeze-all group. However, as this is the first RCT of a freeze-all strategy including GnRH agonist trigger, a double-blinded design was chosen to minimise differences between the two treatment arms and gonadotropin dosing is decided on independently of allocation to treatment group, as this is done prior to randomisation. In addition, even though a strategy combining GnRH agonist trigger and freeze-all is near OHSS free, increasing gonadotropin dosing would nonetheless add a potential risk of early OHSS in the patients.

The primary endpoint of this study is to investigate ongoing pregnancy rates per randomised patient after the first potential blastocyst transfer. Cumulative rates are additionally planned to be calculated, but as the number of aspirated oocytes is expected to be the same in both treatment groups due to gonadotropin dosing being decided on independently of allocated treatment group, the effect of the freeze-all strategy on the results of the first transfer may be diluted with the inclusion of additional FETs.

The strengths of this study include the design as a multicentre randomised controlled double-blinded trial as well as preregistration and publication of the study protocol for more transparency. The investigation of several outcome measures related to different aspects of success parameters, including quality of life may furthermore add important information as regards the future potential of the freeze-all strategy in assisted reproduction.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: ANA, AP and SS participated in the conception, design and writing of the study protocol. KL, HSN and CB contributed to the revision and editing of the study protocol. AP, SS, KL, JB, LP, ANA, HSN, CB, PH, MB, ALM and SOS will be involved in the recruitment of patients and the acquisition of data. SS wrote the first draft of this manuscript. AZ was involved in developing the laboratory criteria for the study. SS, AP, ANA, PH, CB, KL, JB, LP, HSN, MB, ALM and SOS were all involved in critical revision of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript to be submitted.

Funding: The study is part of and fully funded by the Reprounion Collaborative study, cofinanced by the European Union, Interreg, V ÖKS.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The Scientific Ethical Committee in the Capital Region Denmark (approval number H-1600-1116) and the Scientific Ethical Committee in Region Skäne in Sweden (approval number Dnr. 2016/654).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: This manuscript is a study protocol. Data from the final study will be shared according to the coming ICJME guidelines.

References

- 1. Calhaz-Jorge C, de Geyter C, Kupka MS, et al. . Assisted reproductive technology in Europe, 2012: results generated from European registers by ESHRE. Hum Reprod 2016;31:1638–52. 10.1093/humrep/dew151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Loutradi KE, Kolibianakis EM, Venetis CA, et al. . Cryopreservation of human embryos by vitrification or slow freezing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril 2008;90:186–93. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cobo A, de los Santos MJ, Castellò D, et al. . Outcomes of vitrified early cleavage-stage and blastocyst-stage embryos in a cryopreservation program: evaluation of 3,150 warming cycles. Fertil Steril 2012;98:1138–46. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.07.1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhu D, Zhang J, Cao S, et al. . Vitrified-warmed blastocyst transfer cycles yield higher pregnancy and implantation rates compared with fresh blastocyst transfer cycles--time for a new embryo transfer strategy? Fertil Steril 2011;95:1691–5. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.01.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shapiro BS, Daneshmand ST, Garner FC, et al. . Evidence of impaired endometrial receptivity after ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization: a prospective randomized trial comparing fresh and frozen-thawed embryo transfers in high responders. Fertil Steril 2011;96:516–8. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.02.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Roque M, Lattes K, Serra S, et al. . Fresh embryo transfer versus frozen embryo transfer in in vitro fertilization cycles: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril 2013;99:156–62. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen ZJ, Shi Y, Sun Y, et al. . Fresh versus frozen embryos for infertility in the polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med 2016;375:523–33. 10.1056/NEJMoa1513873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kansal Kalra S, Ratcliffe SJ, Milman L, et al. . Perinatal morbidity after in vitro fertilization is lower with frozen embryo transfer. Fertil Steril 2011;95:548–53. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.05.049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Devroey P, Polyzos NP, Blockeel C. An OHSS-Free Clinic by segmentation of IVF treatment. Hum Reprod 2011;26:2593–7. 10.1093/humrep/der251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Youssef MA, Van der Veen F, Al-Inany HG, et al. . Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agaonist versus HCG for oocyte triggering in antagonist-assisted reproductive technology. The Cochrane Database syst rev 2014;31:CD008046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pinborg A. To transfer fresh or thawed embryos? Semin Reprod Med 2012;30:230–5. 10.1055/s-0032-1311525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Engmann L, Benadiva C, Humaidan P. GnRH agonist trigger for the induction of oocyte maturation in GnRH antagonist IVF cycles: a SWOT analysis. Reprod Biomed Online 2016;32:274–85. 10.1016/j.rbmo.2015.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.