Abstract

Introduction

Several societies have produced and disseminated clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) for the symptomatic management of fever in children. However, to date, the quality of such guidelines has not been appraised.

Objective

To identify and evaluate guidelines for the symptomatic management of fever in children.

Methods

The research was conducted using PubMed, guideline websites, and Google (January 2010 to July 2016). The quality of the CPGs was independently assessed by two assessors using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II (AGREE II) instrument, and specific recommendations in guidelines were summarised and evaluated. Domain scores were considered of sufficient quality when >60% and of good quality when >80%.

Results

Seven guidelines were retrieved. The median score for the scope and purpose domain was 85.3% (range 66.6–100%). The median score for the stakeholder involvement domain was 57.5% (range 33.3–83.3%) and four guidelines scored >60%. The median score for the rigour of development domain was 52.0% (range 14.6–98.9%), and only three guidelines scored >60%. The median score for the clarity of presentation domain was 80.9% (range 50.0–94.4%). The median score for the applicability domain was 39.3% (8.3–100%). Only one guideline scored >60%. The median score for the editorial independence domain was 48.84% (0–91.6%); only three guidelines scored >60%.

Conclusion

Most guidelines were recommended for use even if with modification, especially in the methodology, the applicability and the editorial independence domains. Our results could help improve reporting of future guidelines, and affect the selection and use of guidelines in clinical practice.

Keywords: Children, guidelines, antipyretics, fever

Strengths and limitation of this study.

To the best of our knowledge this is the first study to appraise guidelines on the symptomatic management of fever with the AGREE II instrument.

Moreover, recommendations dealing with symptomatic management of fever have been extracted and resumed in comparative tables, focusing on possible gaps and common messages between the guidelines.

The AGREE methodology does not provide a threshold for discrimination between high quality and low quality guidelines.

Searching may not have been exhaustive; therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility that some guidelines may have been omitted from this study.

Introduction

Fever is one of the most common clinical reasons for paediatric consultations, accounting for about one-third of all presenting conditions in children.1–3

Concerns of parents/tutors/caregivers about serious causes of fever (ie, severe bacterial infections) and misconceptions about fever as a sufficient trigger of brain damage have led to the spreading of ‘fever-phobia’.1 4 5 Several studies have reported a high percentage of parents/tutors/caregivers administering antipyretics even when there is minimal or no fever, with wrong dosages or with insufficient intervals between the doses.4–6 Fever is a physiologic mechanism with beneficial effects in fighting infection and it is not associated with long-term neurologic complications.7 The only purpose for treating fever in children must be to relieve the child's discomfort and not to lower the body temperature.8

The inappropriate management of fever may delay the diagnosis and increase the risk of antipyretic overdose. Moreover, other factors may increase drug toxicity such as the alternate/combined use of two antipyretics,9 the use of rectal formulations,10 and the administration of these drugs in the presence of contraindicated underlying diseases.11 Finally, overtreatment may have a significant economic impact in low-middle income and high income countries.

In order to rationalise and standardise the symptomatic management of fever in children, national health agencies and scientific societies have produced and disseminated clinical guidelines. It has been demonstrated that parents/tutors do not fully comply with these recommendations, as they used to employ traditional physical means and administer antipyretics with inappropriate indications and posology.3 12–16 Moreover, important discrepancies have been reported between the practices of healthcare professionals and the recommendations of guidelines.17–19

Several barriers to applying these guidelines in clinical practice have been identified.19–22 Thus, we conducted this study to identify and evaluate the quality of the international clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) for the use of antipyretics and physical methods in children with fever, focusing on discrepancies.

Methods

Primary outcomes

The primary outcomes of the study were to encourage the improvement of the quality of guidelines, to reinforce the messages of common recommendations, and to stimulate further research on discordant recommendations and the issues of international guidelines in order to unify medical behaviour.

Guidelines research

The search for guidelines for the symptomatic management of fever in children was carried out using documents issued by national scientific societies or by government organisations between January 2010 and July 2016 in every language, through the use of appropriate keywords and the following search engines: PubMed; National Guideline Clearinghouse (www.guideline.gov); NICE: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (www.nice.org.uk); Canadian CPG Infobase: Clinical Practice Guidelines Database (www.cma.ca/En/Pages/clinical-practice-guidelines.aspx); Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) (www.sign.ac.uk); Australian Clinical Practice Guidelines (http://www.clinicalguidelines.gov.au/);%20and Guidelines International Network (http://www.g-i-n.net/). Additional research was conducted on Google. In this research we used the following keywords: ‘guideline’, ‘fever’, ‘children’, and ‘antipyretics’, (see ‘Search strategy’ in supplementary material 1). The search was limited to January 2010 and not earlier in order to evaluate only the most recent and updated guidelines.

bmjopen-2016-015404supp001.pdf (140KB, pdf)

Exclusion criteria

Guidelines that did not focus on the management of fever as a symptom/sign, or were not original or were issued on a regional level, were excluded, as well as any documents that were not guidelines (such as position papers and reviews).

Quality evaluation

Two assessors, one with experience in developing and evaluating guidelines (EC) and another assessor (BB), used the online training tools recommended by the AGREE collaboration before conducting appraisals.23 They independently evaluated the included guidelines using the AGREE II instrument,23 which consists of a total of 23 items in six domains: ‘Scope and purpose’, ‘Stakeholder involvement’, ‘Rigour of development’, ‘Clarity of presentation’, ‘Applicability’, and ‘Editorial independence’. Each item was rated on a seven-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). A scaled domain percentage score was calculated, according to the AGREE II methodology,23 as follows: (obtained score−minimum possible score)/(maximum possible score−minimum possible), where the ‘obtained score’ is the sum of the appraisers scores per each item, making it possible to consider the natural discrepancies between the two appraisers.

Although the domain scores are useful for comparing guidelines and attest whether a guideline should be recommended for use, the AGREE II instrument does not set minimum domain scores or patterns of scores across domains to differentiate between high quality and poor quality guidelines. These decisions should be made by the users and guided by the context in which AGREE II is being used.23 Then, as reported in previous studies,24 25we considered a value >60% as sufficient quality score and a value >80% as a good quality score.

On completing the 23 items, the appraisers provided the overall assessment of each guideline, and decided which guideline was recommendable, with or without modifications, and which was not recommendable. This choice was the result of the six domains’ scores and of the personal judgement of the appraisers. To resolve discrepancies between the two assessors, a method was used from a previous study: if the scores assigned by the assessors differed by 1 point the lower score was used; if they differed by 2 points they were averaged; and if they varied by ≥3 points a consensus was reached after a discussion.24 25 We decided to recommend without modification the guidelines with an overall score equal to 7, to recommend with modification the guidelines with an overall score ≥4 but <7, and not to recommend the guidelines with an overall score ≤3.

Comparison of recommendations

Recommendations regarding the symptomatic management of fever in children, reported in the selected guidelines, have been extracted and summarised in comparative tables focusing on possible gaps and common messages.

Results

Guideline selection

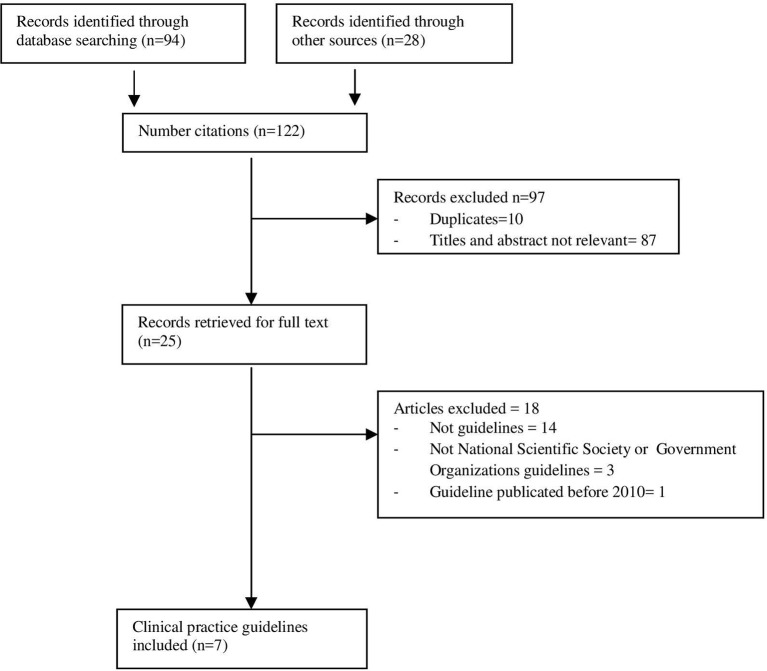

A total of 122 records were initially identified, of which, after screening titles and abstracts, 97 were excluded because they were irrelevant or duplicates. The remaining 25 records were retrieved for full text.2 26–49 Among these, 18 documents were excluded because they were not guidelines26 28 29 31–38 40–42 or they were not medical societies’ or health government guidelines39 43 46; one of the guidelines was excluded because the original publication date was before 2010.45 Finally, seven CPGs were selected2 27 30 44 47–49 (figure 1). The characteristics of the included guidelines are presented in table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of searching and selecting guidelines.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the retrieved clinical practice guidelines

| Title | Year of publication | Country/region | Level of development | Organisation | Authors number | Number of references |

| Clinical report – fever and antipyretic use in children2 | 2011 | USA | National | American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) | 28 | 85 |

| Update of the 2009 Italian Pediatric Society guidelines about management of fever in children27 | 2014 | Italy | National | Italian Pediatric Society (SIP) | 21 | 162 |

| Management of acute fever in children: guideline for community healthcare providers and pharmacists30 | 2013 | South Africa | National | No specified | 8 | 23 |

| Feverish illness in children: assessment and initial management in children younger than 5 years44 | 2013 | UK | National | National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) | 17 | 138 (2013 update) + 289 (2007 edition) |

| Children and infants with fever – acute management47 | 2010 | Australia/NSW | New South Wales, Australia | New South Wales (NSW) Ministry of Health |

16 | 36 |

| Management of fever without focus in children (excluding neonates) clinical guideline48 | 2013 | Australia/ South | South Australia | South Australia (SA) Ministry of Health |

Not specified | 25 |

| WHO pocket book of hospital care for children: guidelines for the management of common childhood illness49 | 2013 | International | WHO | 17 | 29 |

AGREE II scores

The domain-standardised scores for selected guidelines and overall recommendations are presented in table 2 and figure 2.

Table 2.

Standardised scores of each domain by AGREE II of guidelines

| Scope and purpose | Stakeholder involvement | Rigour of development | Clarity of presentation | Applicability | Editorial Independence |

Overall assessment | |

| AAP2 | 75% | 41.60% | 23.90% | 83.30% | 27.10% | 83.30% | 5. Recommended with modifications |

| SIP27 | 94.40% | 80.50% | 89.60% | 94.40% | 27.10% | 91.60% | 6. Recommended with modifications |

| South African30 | 88.80% | 61.10% | 31.20% | 83.30% | 8.30% | 50% | 4. Recommended with modifications |

| NICE44 | 100% | 83.30% | 98.90% | 83.30% | 100% | 50% | 7. Recommended |

| NSW47 | 66.60% | 41.60% | 16.00% | 50% | 33.30% | 0% | 3. Not recommended |

| SA48 | 83.30% | 33.30% | 14.60% | 77.70% | 16.60% | 0% | 3. Not recommended |

| WHO49 | 88.90% | 61.10% | 89.60% | 94.40% | 62.50% | 67% | 6. Recommended with modifications |

AAP, American Academy of Pediatrics; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; NSW, New South Wales Ministry of Health; SA, South Australian Ministry of Health; SIP, Italian Pediatric Society.

Figure 2.

Standardised scores of each domain by AGREE II of guidelines—histogram.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP)2 guideline has good scores in clarity of presentation and editorial independence domains, sufficient score in scope and purpose, with low scores in stakeholder involvement, rigour of development and applicability domains.

The Italian Pediatric Society (SIP)27 guideline has good scores in scope and purpose, stakeholder involvement, rigour of development, clarity of presentation and editorial independence domains with a low score in applicability domain.

The South African30 guideline has good scores in scope and purpose and clarity of presentation, sufficient score in stakeholder involvement, but low scores in rigour of development, applicability and editorial independence domains.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)44 guideline has good scores in scope and purpose, stakeholder involvement, rigour of development, clarity of presentation and applicability domains with a low score in editorial independence.

The New South Wales Ministry of Health (NSW)47 guideline has a sufficient score in the scope and purpose domain, but low scores in all the others.

The South Australian Ministry of Health (SA)48 guideline has a good score in scope and purpose, a sufficient score in clarity of presentation domain, but low scores in the others.

The WHO49 guideline has good scores in scope and purpose, rigour of development, clarity of presentation and sufficient scores in stakeholder involvement, applicability and editorial independence domains.

Scope and purpose

The median score for the scope and purpose domain was 85.28% (range 66.6–100%).

Most guidelines clearly described their overall objectives, health questions and target populations. The NSW guideline has the lowest score.47

Stakeholder involvement

The median score for the stakeholder involvement domain was 57.5% (range 33.30–83.30%). Only the SIP, South African, NICE, and WHO guidelines scored above 60% for this domain,27 30 44 49 whereas the AAP, NSW and SA guidelines did not consider the views and preferences of the target population.2 47 48 No guideline clearly described their members’ roles in the guideline development process. Only the SIP and NICE guidelines had methodology experts included in the guideline development group.27 44 Only in the NICE guideline were there health economists among the guideline authors.44

Rigour of development

The median score for the rigour of development domain was 51.97% (range 14.60–98.90%). Only the SIP, NICE, and WHO guidelines scored >60% because they used systematic methods of searching for evidence and for formulating recommendations27 44 49; only the NICE and WHO CPGs clearly described methods for conducting external reviews44 49; and only the NICE and WHO CPGs described their procedures for updating guidelines.44 49

Clarity of presentation

Most guidelines provided specific, unambiguous and easily identifiable recommendations. The median score for the clarity of presentation domain was 80.9% (range 50–94.4%). Only the NSW guideline scored <60%.47

Applicability

The median score for the applicability domain was 39.3% (8.3–100%). Only the NICE guideline scored >60%.44 Most guidelines did not describe the facilitators and barriers of their applications and did not sufficiently consider the costs of applying their recommendations; only the NICE guideline involved a health economist in finding and analysing cost information.44Only the AAP and SA guidelines did not provide any tool or suggestions for putting the recommendations into practice.2 48

Editorial independence

The median score for the editorial independence domain was 48.84% (0–91.6%); only the AAP, SIP and WHO CPGs scored >60%.2 27 49 The NWS and SA CPGs did not clearly provide financial support information.47 48 Although the WHO guideline reported the funding source, it did not specify the possible funding influence on the CPG content.49 Moreover, only the AAP, SIP and WHO guidelines include a conflict of interest statement by the guideline development group.2 27 49

Overall assessment

Based on the six domain scores and on a personal judgement, the AAP, SIP, South African and WHO guidelines were recommended with modifications,2 27 30 49 only the NICE CPG was recommended without modifications,44 and the NSW and SA CPGs were not recommended.47 48

Summary of recommendations

Specific recommendations have been identified and summarised in table 3, as well as common and discordant messages.

Table 3.

Specific recommendations

| Specific recommendations | AAP2 | SIP27 | South- Africa30 | NICE44 | NSW47 | SA48 | WHO49 |

| Age of target population | Not specified | 0–18 years | Not specified | <5 years | 1 month −5 years | <3 years | <5 years |

| Indications and treatment goals | |||||||

| Antipyretics are indicated to improve overall comfort of the febrile child | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Antipyretics should not be used with the aim of reducing body temperature | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | nr | ✔ |

| Fever response to antipyretics is not a predictor of serious illness | nr | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | nr | nr |

| Antipyretics do not prevent febrile convulsions | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | nr | ✔ | nr |

| Antipyretics are not indicated to prevent vaccine reaction | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | nr | nr | nr | nr |

| Antipyretics are not indicated to treat vaccine reaction | nr | nr | ✔ | nr | nr | nr | nr |

| Physical management | |||||||

| The use of physical devices is not recommended | nr | ✔ | nr | nr | ✘* | nr | ✘† |

| Children with fever should not be under-dressed or over-wrapped | nr | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✘* | nr | ✘† |

| The use of alcoholic baths is not an appropriate cooling method | ✔ | ✔ | nr | nr | ✔ | nr | nr |

| Tepid sponging is not recommended for the treatment of fever | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | nr | nr |

| Pharmacological management | |||||||

| Consider using either paracetamol or ibuprofen in children with fever who appear distressed | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Paracetamol from the age of | 3 months‡ | Birth§ | 3 months | nr | Birth | Birth§ | 2 months |

| Ibuprofen from the age of | 6 months | nr | 3 months | nr | 6 months | 2 months | |

| Paracetamol oral dose (mg/kg/dose) | 10–15 (Sup. table 1) |

10–15 (Sup. table 1) |

15 (Sup. table 1) |

nr | 15 (Sup. table 1) |

15 (Sup. table 1) |

10–15 (Sup. table 1) |

| Paracetamol dose in newborns (mg/kg/dose) | nr | – 10 (<32 weeks) – 10–15 (>32 weeks) (Sup. table 2) |

nr | nr | nr | 15 (Sup. table 2) |

✘ |

| Initial loading dose of paracetamol (oral, rectal) is not recommended | ✔ | nr | nr | nr | nr | nr | nr |

| Ibuprofen dose mg/kg/dose | 10 | 10 (Sup. table 3) |

10 (Sup. table 3) |

nr | 10 (Sup. table 3) |

5–10 (Sup. table 3) |

5–10 (Sup. table 3) |

| Combination of paracetamol/ibuprofen is not recommended | ✘¶ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | nr | ✔ | nr |

| Alternating paracetamol/ibuprofen is not recommended | ✘¶ | ✔ | ✔ | ✘** | ✔ | ✘** | nr |

| Oral administration of paracetamol is preferred to rectal | nr | ✔ | nr | nr | nr | nr | nr |

| Rectal administration is allowed only if the oral is not feasible | nr | ✔ | nr | nr | nr | nr | nr |

| Mefenamic acid from 6 months of age may be an alternative to ibuprofen in children with fever | nr | nr | ✔ | nr | nr | nr | nr |

| Doses have to be calculated on weight, not on age | nr | ✔ | ✔ | nr | nr | nr | nr |

| Avoid combination of antipyretics and ‘cough and cold medicines’ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | nr | nr | nr | nr |

| Use only the measuring device provided | nr | ✔ | ✔ | nr | nr | nr | nr |

| Contraindications/precautions | |||||||

| Ibuprofen does not seem to worsen asthma symptoms | ✔ | ✔†† | Caution | nr | nr | Caution | nr |

| Paracetamol does not seem to worsen asthma symptoms | ✔ | ✔ | nr | ✔ | nr | nr | nr |

| Ibuprofen is indicated in children with dehydration | Caution | ✘ | Caution | Not conclusive | nr | Caution | nr |

| Ibuprofen is indicated in children with varicella | Caution | ✘ | Caution | Not conclusive | nr | nr | nr |

| Caution using antipyretics in other chronic diseases | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | nr | nr | nr | nr |

| Intoxication | |||||||

| In the case of suspected poisoning with paracetamol take the child to emergency department or poison centre | nr | ✔ | nr | nr | nr | nr | ✔‡‡ |

✔agree; ✘disagree; nr, not reported; Sup. table: supplementary table.

*Unwrapping an overdressed child is appropriate.47

†Undressing the child t is recommended to reduce the fever.49

‡In children <3 months it can be administered only after medical advice.2

§In children <3 months it can be administered by adapting the dosage and intervals to the gestational age.47 48

¶Insufficient evidence to support or refuse the routine use of combination treatment.2

**Alternating the two drugs is possible if discomfort persists or recurs using only one antipyretic.44 48

††Ibuprofen is contraindicated in known cases of asthma related to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.27

‡‡Management of paracetamol intoxication is reported in chapter 1: Triage and emergency conditions/common poisoning.49

AAP, American Academy of Pediatrics; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; NSW, New South Wales Ministry of Health; SA, South Australian Ministry of Health; SIP, Italian Pediatric Society.

bmjopen-2016-015404supp002.pdf (46.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-015404supp003.pdf (38.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-015404supp004.pdf (27.3KB, pdf)

Common messages

Antipyretics are indicated only in cases of discomfort associated with fever and not with the sole aim of reducing body temperature.

Recommended antipyretics are paracetamol or ibuprofen, according to the child's age, weight and characteristics.

The use of antipyretics does not prevent either febrile convulsions or reactions to vaccines.

Tepid sponging and alcoholic baths are not recommended for the treatment of fever.

The use of cough and cold medicine is discouraged because of the risks of overdoses and interactions.

Caution is recommended using antipyretics in chronic diseases such as pre-existing hepatic and renal impairment or in cases of diabetes, cardiac disease and severe malnutrition.

In asthmatic children with fever, paracetamol does not seem to worsen asthma symptoms.

Divergent messages

The physical method of unwrapping/uncovering children with fever is contraindicated by the SIP, South African and NICE CPGs25 28 42 and indicated by the NWS and WHO CPGs.47 49

The alternate use of two antipyretics is discouraged by most of the guidelines with the exception of the NICE and SA CPGs.44 48 These two guidelines permit the alternate use only if the discomfort persists after the administration of one antipyretic.44 48

The minimum age for administering paracetamol varies from birth (SIP, NWS, SA27 47 48) to 2 months (WHO49), to 3 months (South African30) (online supplementary file 2).

The posology of paracetamol varies in terms of dosage per single administration (10–15 or 15 mg/kg/dose), of intervals between doses (4 hour, 4–6 hour or 6 hour) and of maximum allowable daily dosage that ranges from 60 mg/kg/day to 90 mg/kg/day (online supplementary file 2).

The posology of paracetamol in newborns27 48 varies by paracetamol dosage per single administration and maximum daily dosages in newborns (online supplementary file 3).

The minimum age for ibuprofen administration ranges from 2 to 3 months (NWS,47 WHO49) to 6 months (AAP2) (online supplementary file 4).

The posology of ibuprofen is divergent in terms of dosage per single administration (5–10 or 10 mg/kg/dose), of intervals between doses (6, 6–8 hours) and maximum daily dosage of 40 mg for all guidelines except the SIP CPG that allows up to 30 mg27(online supplementary file 4).

The use of ibuprofen in asthmatic patients is contraindicated in the SIP CPG only in patients with asthma related to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs but indicated with caution in all asthmatic patients by the South African and SA CPGs.30 48

The use of ibuprofen in children with dehydration is contraindicated by the SIP CPG,27 but recommended with caution by the AAP, South African and SA CPGs.2 30 48

The use of ibuprofen in the case of varicella is contraindicated by the SIP CPG27 and advised with caution by the AAP and South African CPGs.2 30

Discussion and conclusions

In the present study a systematic search of the available national guidelines regarding the management of fever in children was performed, and key messages have been summarised. Overall, only seven guidelines were retrieved, which is less than expected considering that fever represents a large part of the practice of healthcare professionals, and how common the use of these drugs is. In particular, only two guidelines (AAP, SIP2 27) focused specifically on the symptomatic management of feverish children, whereas the other five guidelines dealt with the other aspects of fever management, including aetiological diagnosis and therapy.

Considering the impact of the quality of the guidelines in their application, we appraised the quality scores of the CPGs with the AGREE II instrument.

Interestingly, lower quality scores were observed in the domains of methodology, applicability and editorial independence, whereas all the guidelines had moderate to high scores in the purpose and objective and the clarity of the recommendations. The methodology analysis showed acceptable results only for the SIP,27 NICE,44 and WHO guidelines49 whereas the AAP,2 South African,30 NWS47 and SA guidelines48 had insufficient scores because they were not based on a systematic review of the literature and they did not provide recommendations explicitly linked to evidence, or because they did not involve all the required members in the guideline development group.

Regarding the ‘applicability’ item, most guidelines did not describe the facilitators and barriers to their application and did not provide audit criteria. Some CPGs lacked a summary document, and educational tools.2 30 This finding is in contrast with the need for clarity and user friendliness suggested by some authors19–22 and should be taken into consideration when developing new guidelines. Information on editorial independence was also neglected in most guidelines.30 44 47 48 Indeed only AAP, SIP and WHO guidelines reported detailed information on potential conflicts of interest.2 27 49 This is particularly important considering that conflicts of interest are the most common source of bias in guideline development.49 One strength of our study is that we used the AGREE II instrument for the first time to assess the methodological quality of guidelines related to fever in children.

The AGREE II instrument is a tool that assesses the methodological rigour and transparency with which a guideline is developed.23 A potential limitation of this method is that there is no threshold for distinguishing between high quality and low quality CPGs. Thus, the guideline quality would be left to the appraisers to identify and the scores of an AGREE II evaluation have to be interpreted with caution and confined to a particular situation. Furthermore, AGREE II does not consider the relative importance of the six domains of quality: rigour of development is considered of equal importance to the other five domains.24 This suggests that the domains of AGREE II should not be weighed equally. If the guideline has a low score on the domain of rigour of development, the corresponding recommendations have a high risk of bias, and the other domains are of little relevance in quality assessment. Another possible limitation of our study is that some guidelines may have been missed by our research.

From a comparison of the recommendations we observe that the guidelines agree on some crucial aspects. In particular, all guidelines agree on prescribing antipyretics only with the aim of relieving the child's discomfort caused by fever and not with the sole aim of reducing body temperature. There is also an agreement on the type of recommended antipyretics which are paracetamol or ibuprofen, according to a child's age, weight and characteristics. Several studies demonstrated the high tolerability of both these drugs with similar efficacy in reducing body temperature.7 9 However, few data are available regarding the impact of antipyretics in reducing the child's discomfort.7 9 The concept of ‘discomfort’ is not easy to define because it varies across different age groups, and may be influenced by the caregiver's perception. Therefore, future research needs to define child discomfort more precisely, and how to measure it using standardised clinical scores.

On the other hand, some messages diverge, either about the use of physical methods or the pharmacological approach. The common physical method to unwrap/uncover children with fever is contraindicated by the SIP, South African and NICE CPGs,27 30 44 but it is considered in the NWS and WHO CPGs.47 49 Furthermore, most guidelines discourage the alternate/combined use of two antipyretics except the NICE and SA CPGs that allow the alternate use of the two drugs, only when distress persists after the administration of one antipyretic.44 48 Alternate use can be associated with better control of body temperature, but no study demonstrated superiority in terms of distress control compared with monotherapy. However, it is certain that alternating two drugs increases the risk of overdose and toxicity.9 A greater consensus from the international scientific community would be desirable on a topic of such wide resonance.

In conclusion, most guidelines issued at national or international levels were of good quality and could be adopted in clinical practice. Nevertheless, the quality of the CPGs could be improved, in particular the methodological, applicability and editorial independence domains. Our study reinforces the messages of concordant recommendations and shines a light on discordant suggestions, and could stimulate the issues of international guidelines in order to unify medical behaviour.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: EC conceptualised and designed the study, used AGREE II instrument to evaluate the retrieved guidelines, drafted the initial manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. BB carried out the initial analysis, used AGREE II instrument to evaluate the retrieved guidelines, drafted the initial manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. LG critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. MdM critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: The study does not includes patient data.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

References

- 1. Crocetti M, Moghbeli N, Serwint J. Fever phobia revisited: have parental misconceptions about fever changed in 20 years? Pediatrics 2001;107:1241–6. 10.1542/peds.107.6.1241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sullivan JE, Farrar HC. Section on clinical pharmacology and therapeutics, Committee on Drugs, fever and antipyretic use in children. Pediatrics 2011;127:580–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bertille N, Fournier-Charrière E, Pons G, et al. . Managing fever in children: a national survey of parents' knowledge and practices in France. PLoS One 2013;8:e83469 10.1371/journal.pone.0083469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Karwowska A, Nijssen-Jordan C, Johnson D, et al. . Parental and health care provider understanding of childhood fever: a Canadian perspective. CJEM 2002;4:394–400. 10.1017/S1481803500007892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Betz MG, Grunfeld AF. 'Fever phobia' in the emergency department: a survey of children's caregivers. Eur J Emerg Med 2006;13:129–33. 10.1097/01.mej.0000194401.15335.c7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lubrano R, Paoli S, Bonci M, et al. . Acetaminophen administration in pediatric age: an observational prospective cross-sectional study. Ital J Pediatr 2016;42:20 10.1186/s13052-016-0219-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kramer MS, Naimark LE, Roberts-Bräuer R, et al. . Risks and benefits of paracetamol antipyresis in young children with fever of presumed viral origin. Lancet 1991;337:591–4. 10.1016/0140-6736(91)91648-E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Richardson M, Lakhanpaul M. Guideline Development Group and the Technical Team. Assessment and initial management of feverish illness in children younger than 5 years: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ 2007;334:1163–4. 10.1136/bmj.39218.495255.AE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hay AD, Costelloe C, Redmond NM, et al. . Paracetamol plus ibuprofen for the treatment of fever in children (PITCH): randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2008;337:a1302 10.1136/bmj.a1302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bilenko N, Tessler H, Okbe R, et al. . Determinants of antipyretic misuse in children up to 5 years of age: a cross-sectional study. Clin Ther 2006;28:783–93. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Matziou V, Brokalaki H, Kyritsi H, et al. . What Greek mothers know about evaluation and treatment of fever in children: an interview study. Int J Nurs Stud 2008;45:829–36. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.04.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Boivin JM, Weber F, Fay R, et al. . [Management of paediatric fever: is parents' skill appropriate?]. Arch Pediatr 2007;14:322–9. 10.1016/j.arcped.2006.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Impicciatore P, Nannini S, Pandolfini C, et al. . Mother's knowledge of, attitudes toward, and management of fever in preschool children in Italy. Prev Med 1998;27:268–73. 10.1006/pmed.1998.0262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Langer T, Pfeifer M, Soenmez A, et al. . Fearful or functional--a cross-sectional survey of the concepts of childhood fever among German and Turkish mothers in Germany. BMC Pediatr 2011;11:41 10.1186/1471-2431-11-41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Taveras EM, Durousseau S, Flores G. Parents' beliefs and practices regarding childhood fever: a study of a multiethnic and socioeconomically diverse sample of parents. Pediatr Emerg Care 2004;20:579–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lava SA, Simonetti GD, Ramelli GP, et al. . Symptomatic management of fever by Swiss board-certified pediatricians: results from a cross-sectional, web-based survey. Clin Ther 2012;34:250–6. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2011.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chiappini E, Parretti A, Becherucci P, et al. . Parental and medical knowledge and management of fever in Italian pre-school children. BMC Pediatr 2012;12:97 10.1186/1471-2431-12-97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Martinot A, Cohen R. [Attributes of elaboration and dissemination strategies that influence the implementation of clinical practice guidelines]. Arch Pediatr 2008;15:656–8. 10.1016/S0929-693X(08)71865-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. May A, Bauchner H. Fever phobia: the pediatrician's contribution. Pediatrics 1992;90:851–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, et al. . Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA 1999;282:1458–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cavazos JM, Naik AD, Woofter A, et al. . Barriers to physician adherence to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug guidelines: a qualitative study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008;28:789–98. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03791.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dans AL, Dans LF. Appraising a tool for guideline appraisal (the AGREE II instrument). J Clin Epidemiol 2010;63:1281–2. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ye ZK, Liu Y, Cui XL, et al. . Critical appraisal of the Quality of Clinical Practice guidelines for stress ulcer prophylaxis. PLoS One 2016;11:e0155020 10.1371/journal.pone.0155020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Holmer HK, Ogden LA, Burda BU, et al. . Quality of clinical practice guidelines for glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. PLoS One 2013;8:e58625 10.1371/journal.pone.0058625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wong T, Stang AS, Ganshorn H, et al. . Cochrane in context: combined and alternating paracetamol and ibuprofen therapy for febrile children. Evid Based Child Health 2014;9:730–2. 10.1002/ebch.1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chiappini E, Principi N, Longhi R, et al. . Management of fever in children: summary of the Italian Pediatric Society guidelines. Clin Ther 2009;31:1826–43. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2009.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hoover L. AAP reports on the use of antipyretics for fever in children. Am Fam Physician 2012;85:518–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. van den Anker JN. Optimising the management of fever and pain in children. Int J Clin Pract Suppl 2013;67:26–32. 10.1111/ijcp.12056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Green R, Jeena P, Kotze S, et al. . Management of acute fever in children: guideline for community healthcare providers and pharmacists. S Afr Med J 2013;103:948–54. 10.7196/SAMJ.7207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. McIntyre J. Management of fever in children. Arch Dis Child 2011;96:1173–4. 10.1136/archdischild-2011-301094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Paul SP, Mayhew J, Mee A. Safe management and prescribing for fever in children. Nurse Prescribing 2011;9:539–44. 10.12968/npre.2011.9.11.539 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pereira GL, Tavares NU, Mengue SS, et al. . Therapeutic procedures and use of alternating antipyretic drugs for fever management in children. J Pediatr 2013;89:25–32. 10.1016/j.jped.2013.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. De Ronne N. [Management of fever in children younger then 3 years]. J Pharm Belg 2010;3:53–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Reshadat S, Shakibaei D, Rezaei M, et al. . Fever management in parents who have children aged 0-5 years. Scientific Journal of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences & Health Services 2012;19:28–33. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Paul SP, Mee A, Mayhew J. The management of fever in children. Independent Nurse 2012;2012 10.12968/indn.2012.19.11.95300 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sallam SA, El-Mazary AA, Osman AM, et al. . Integrated management of childhood illness (IMCI) approach in management of children with high grade fever ≥ 39°. Int J Health Sci 2016;10:239–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pirker A, Pirker M. [Management of fever in children]. Ther Umsch 2015;72:15–17. 10.1024/0040-5930/a000631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tantracheewathom T. Fever of unknown origin in children: approach and management: Vajira Medical Journal, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Walls T. Evaluation and management of fever in children. N Z Med J 2010;123:15–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Long SS. Diagnosis and management of undifferentiated fever in children. J Infect 2016;72(Suppl: 68-76):S68–S76. 10.1016/j.jinf.2016.04.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Long D, Flatley C, Williams T, et al. . Occurrence, management and outcome of fever in critically ill children. Australian Critical Care 2016;29:123 10.1016/j.aucc.2015.12.035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Medical City King Saud University (KSUMC. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline for management of fever of uncertain source in infants 60 days of age or less. 1st Edition, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 43. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Feverish illness in children: assessment and initial management in children younger than five years, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 44. M29 NHG Clinical Practice Guideline Feverish illness in Children. BohnStafleu van Loghum. The Netherlands: Part of Springer Media, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center. Evidence based clinical practice guideline for fever of uncertain source in children 2 to 36 months of age, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 46. New South Wales (NSW) Kids and Families. Children and Infants with fever - Acutemanagement, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 47. SA Child Health Clinical Network. Fever without a focus in infants and children excluding the newborn, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 48. World Health Organization. Pocket book of Hospital Care for Children: guidelines for the management of Common Childhood Illnesses, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Detsky AS. Sources of bias for authors of clinical practice guidelines. CMAJ 2006;175:1033–5. 10.1503/cmaj.061181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-015404supp001.pdf (140KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-015404supp002.pdf (46.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-015404supp003.pdf (38.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-015404supp004.pdf (27.3KB, pdf)