Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Research on peer specialists (individuals with serious mental illness supporting others with serious mental illness in clinical and other settings), has not yet included the measurement of fidelity. Without measuring fidelity, it’s unclear if the absence of impact in some studies is attributable to ineffective peer specialist services or because the services were not true to the intended role. This paper describes the initial development of a peer specialist fidelity measure for two content areas: services provided by peer specialists and factors that either support or hamper the performance of those services.

METHODS

A literature search identified 40 domains; an expert panel narrowed the number of domains and helped generate and then review survey items to operationalize those domains. Twelve peer specialists, individuals with whom they work, and their supervisors participated in a pilot test and cognitive interviews regarding item content.

RESULTS

Peer specialists tended to rate themselves as having engaged in various peer service activities more than supervisors and individuals with whom they work. A subset of items tapping peer specialist services “core” to the role regardless of setting had higher ratings. Participants stated the measure was clear, appropriate, and could be useful in performance improvement.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

Although preliminary, findings were consistent with organizational research on performance ratings of supervisors and employees made in the workplace. Several changes in survey content and administration were identified. With continued work, the measure could crystalize the role of peer specialists and aid in research and clinical administration.

The role of peer specialists has evolved over the last four decades. Peer support began with groups providing informal support, opportunities for greater independence, and concrete assistance that filled in the gaps of the traditional mental health system (Davidson et al., 1999). The current role of peer specialist is a variant that came from those informal peer support groups, which some studies showed were not always well attended (Chinman, Kloos, O’Connel, & Davidson, 2002; Kaufmann, Schulberg, & Schooler, 1994; Luke, Roberts, & Rappaport, 1993). The peer specialist role was a way to address low group attendance by proactively delivering peer support to clients in need. Although peer specialists tend to engage in more hierarchical relationships than found in peer support groups, they still “draw upon their lived experiences to share ‘been there’ empathy, insights, and skills, serve as role models, inculcate hope, engage patients in treatment, and help patients access supports [in the] community” (pgs. 1315–1316, Chinman et al., 2008). More recently, peer specialists have become more professionalized. A majority of states’ Medicaid reimburse for peer specialist services, and several organizations offer training and certification that qualify peer specialists to deliver reimbursable services. The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) has developed specific competencies for their nationwide workforce of approximately 1100 peer specialists; the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration has developed competencies for peer specialists (SAMHSA, 2015); and initial work has been done to delineate the job role of peer specialists in the VHA (Gill, Murphy, Burns-Lynch, & Swarbrick, 2009).

Despite the evolution and professionalization of peer specialists, there is not a strong consensus on the core components of the role (Rebeiro Gruhl, LaCarte, & Calixte, 2015). The literature describes a wide range of services and activities provided by peer specialists, including: promoting hope, socialization, recovery, self-advocacy and developing natural supports and community living skills. Other typical services include sharing personal experiences, serving as a role model, encouraging self-determination and personal responsibility; promoting wellness, addressing hopelessness; assisting in communications with clinical providers, educating clients about their illnesses, facilitating illness management, and combating stigma in the community (Chinman et al., 2014; Landers & Zhou, 2011; Salzer, Schwenk, & Brusilovskiy, 2010).

While the effectiveness of peer specialists has been evaluated in nearly two dozen outcome studies, little has been done to empirically evaluate the quality of the services delivered by peer specialists. Several reviews (e.g., Chinman et al., 2014; Davidson, Chinman, Sells, & Rowe, 2006) have concluded there is evidence that peer specialists added to a clinical team or delivering a specific recovery curriculum like Wellness Recovery Action Planning can improve outcomes such as decreased hospitalization, increased client activation, greater treatment engagement, more satisfaction with life situation and finances, better quality of life, less depression and fewer anxiety symptoms. More narrowly defined meta-analyses that only include randomized trials have found less impact (Fuhr et al., 2014; Lloyd-Evans et al., 2014; Pitt et al., 2013). However, none of the outcome studies included in any of the reviews measured the degree to which the peer specialist services were delivered with fidelity—that is, delivering peer services as intended. Health services research paradigms suggest that it is critical to simultaneously assess both the quality of the service (i.e., fidelity) and its outcomes to truly understand the impact of a service (Donabedian, 1966).

Recent studies of the peer specialist position offer guidance on conceptualizing fidelity. In particular, researchers have attempted to delineate the peer specialist job role (Gill et al., 2009) and to determine the key mechanisms of peer specialist effectiveness (Gidugu et al., 2015). These studies use different methodologies: Gill and colleagues used role delineation methodology and interviewed 7 Peers and their 2 supervisors about what their job entails. Gidugu and colleagues interviewed clients of peer specialists, and did a comprehensive qualitative evaluation of the experience of receiving peer specialist services. Both articles provide categorization of the tasks and activities of peer specialists. Our project was an effort to develop a peer specialist fidelity measure, and these studies provided important guidance in categorizing the peer specialist services that emerged as important.

Measuring the fidelity of peer specialist activity may lead to improvements in the peer specialist role, based on a review of fidelity measures in psychiatric rehabilitation research by Bond, Evans, Salyers, Williams, and Kim (2000a). First, Bond et al. (2000a) describe multiple examples of how fidelity tools helped to increase the clarity of various treatment models. For example, early fidelity measures for Assertive Community Treatment (McGrew, Bond, Dietzen, & Salyers, 1994; Teague, Bond, & Drake, 1998) and Individual Placement and Support (Bond, Becker, Drake, & Vogler, 1997) helped improve their conceptual clarity in the research literature well after both treatments had been developed. Second, fidelity scales have helped identify the critical components that have been associated with outcomes for models like Assertive Community Treatment, and could do the same for peer specialists. Finally, consistent inclusion of a peer specialist fidelity measure in future outcome studies could help better characterize the relationship between fidelity and outcomes, improving the conclusions of such research. Without any measurement of peer specialist service fidelity, it is not clear if the absence of impact found in some studies is because the peer specialist work is not effective or because the services delivered were not true to the peer specialist’s intended role. Failure to measure peer specialist service fidelity in these studies may be in large part because no instrument exists to measure it.

Fidelity can be measured in multiple ways: unobtrusively (e.g. reviewing notes or logs), direct observation, indirect observation (such as video or audio recordings of interventions), by interview, or self-report. We chose self-report because our very practical goal was to develop a measure of peer specialist fidelity which could be administered and analyzed in a relatively simple way, with the eventual aim of broad scale dissemination of the instrument in the VHA, where the use of peer specialists is now widespread across nearly 150 medical centers. Ultimately, we developed the measure to be applicable wherever peer specialists are providing ongoing support to clients in various mental health settings. Previous work on the development of fidelity instruments provided a methodological framework to guide our process. Century, Rudnick, and Freeman (2010) describe three streams of work that contribute to current thinking on measuring fidelity: focus on “program integrity” (Dane & Schneider, 1998); measuring key program components (Bond, Evans, Salyers, Williams, & Kim, 2000b); and determining critical elements for both the structure of the program and the process by which it is implemented (Mowbray, Holter, Teague, & Bybee, 2003). Mowbray et al. (2003) also provide three helpful steps in developing a fidelity measure; 1) Identify and specify fidelity criteria, 2) Measure fidelity and 3) Assess the reliability and validity of fidelity criteria. This paper describes the process used for the first two steps, and initial work on assessing validity of the instruments by conducting a small pilot.

METHODS

We used a three step method to develop a fidelity measure for peer specialists. First, because no definitive research exists to identify the critical components of peer specialist work, we did an extensive literature review, looking for any aspects of peer specialist services that were associated with program success. Second, we coded appropriate articles from the literature review to develop a set of domains, or areas that emerged as critical to the peer specialist role. Finally, we used an iterative process with an expert panel to review and rate the domains, and the items developed from them, for their inclusion in the measure. This created a “multi-method, multi-informant approach” for identifying the critical elements, as recommended by Mowbray et al. (2003 p. 318). Also, organizational researchers suggest that obtaining data from multiple sources is best (Donaldson & Grant-Vallone, 2002). Therefore, we developed three parallel versions of the measure designed to be answered separately by 1) peer specialists, 2) their supervisors, and 3) clients with whom they provided services. Following the development of the instruments, we pilot tested them with a convenience sample of peer specialists, supervisors and Veterans (total n=12). We conducted a cognitive interview with each of these participants to assess their understanding of the measure. The study was reviewed by the local IRB and deemed to be a quality improvement project, which means formal consent was not required. However, all participation in the study was voluntary and the data was kept confidential. We scored and analyzed the data from this small sample as an initial look at validity. After the instruments were finalized, we organized the domains into categories guided by the work of Gill et al. (2009). Each of these steps is described in the following paragraphs.

Literature review

Search terms were developed for two areas: 1) peer specialist services helpful to those with serious mental illness (these are service factors, including “the ways in which services were delivered” (Century et al., 2010, p. 201) and 2) facilitators and barriers associated with successful implementation of peer specialists (implementation factors). These two areas are consistent with the call by Mowbray et al. (2003) to focus on critical elements for both the structure of a program and the process by which it is implemented. For the literature review, a peer specialist was defined as an individual with serious mental illness who was trained and hired to provide services in a traditional clinical mental health setting. This definition encompasses most of the peer specialists working in the VHA.

We searched Ovid(R) Medline, PsychINFO, Books@Ovid(R) Medline in Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, Ovid(R) Daily Update for references in English between January 1985 and October 2014. This date range covers the majority of time that peer specialists have been employed in clinical mental health settings, as well as a key period of literature development. Given there is lack of specificity about which peer specialist services and implementation factors are critical for successful outcomes, we used several variations of the term “peer specialist” and other terms that would identify a wide range of domains from the peer specialist field. We also manually reviewed the reference lists of several published reviews of peer specialist outcome studies to ensure all the appropriate studies were located (Chinman et al., 2014; Doughty & Tse, 2005; Pitt et al., 2013; Repper & Carter, 2011; Rogers, Farkas, Anthony, Kash, & Maru, 2009; Simpson & House, 2002; Wright-Berryman, McGuire, & Salyers, 2011). This search yielded 1495 articles.

We used the following criteria to exclude articles: was outside the above date range, was not peer reviewed, peer specialist did not engage in one on one interactions at all (only ran groups such as Vet-to-Vet), peer specialist did not work in a clinical setting (e.g., clubhouse, drop-in, online warm line), and focus was not on serious mental illness. Using these exclusion criteria, two researchers first reviewed the articles by the titles and abstracts for appropriateness and excluded 1388 articles, with 91.4% agreement. The remaining 107 articles were reviewed in detail, and an additional 15 articles were excluded, primarily because the peer specialists were not working directly with clients in a clinical setting. The two reviewers had 100% agreement on this second step. The remaining 92 articles were abstracted and coded to identify any text that mentioned services the peer specialist provided that improved program success or any implementation factor that emerged. No pre-existing codes were used, but as new codes were created, the coder then repeated that code with subsequent text on the same factor. Example codes for a helpful peer specialist service were “role modeling”, “help clients access community supports”, and “promote knowledge of illness”. Example codes of implementation factors that were helpful were “leadership oversight”, “program champions seeded at each site”, and “training (40 hours)”. This process was iterative, involving several meetings in which the project team members discussed the best way to conceptualize each code so that it captured unique information. The result of these meetings was a list of 20 codes for peer specialist services and 20 for implementation factors (see Table 1). These codes became the domains that were presented to the expert panel for further evaluation and later used to generate specific survey items.

Table 1.

Selected domains

| Peer specialist services | Implementation factors | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Peer specialists promote hope | Non-peer staff receive education about peer role |

| 2 | Peer specialists serve as role model | Peers receive education and training |

| 3 | Peer specialists share recovery story | local training of peers |

| 4 | Peer specialists help reduce isolation | Relationship between peer and non-peer co-workers |

| 5 | Peer specialists do recovery planning | Support for peer role at higher organizational level |

| 6 | Peer specialists have flexible time and meeting places | Peer specialist role clarity |

| 7 | Peer specialists engage clients in treatment | Dual role as client and staff |

| 8 | Peer specialists increase client’s participation in own illness management | Peer specialists receive clinical supervision |

| 9 | Peer specialists help link clients to community resources | Peer to peer support |

| 10 | Peer specialists serve as a liaison between staff and clients | Equitable work environment |

| 11 | Peer specialists increase access to services | Peer performance standards |

| 12 | Peer specialists run recovery groups | Regular performance feedback |

| 13 | Peer specialists focus on strengths | Peer specialist has input in treatment of clients |

| 14 | Peer specialists provide empathy | Ongoing collaboration between peer specialists and non-peer staff |

| 15 | Peer specialists promote empowerment | Peer specialists have a flexible work schedule |

| 16 | Peer specialists develop a trusting relationship | Caseload limits |

| 17 | Peer specialists are a friend | Documentation |

| 18 | Peer specialists teach coping skills | Peers adopting an exclusively non-peer role |

| 19 | Peer specialists teach problem solving | Difficulties transitioning into a professional role |

| 20 | Peer specialists help their team focus on recovery | Client involvement |

Expert panel

The expert panel was made up of 19 individuals from the United States; 13 (68%) were associated with the VHA, including three peer specialists, five peer specialist supervisors, two researchers, and three national VHA peer specialist administrators. Of those outside VHA, two were researchers and four were national experts in employing and managing peer specialists.

The expert panelists attended three 90 minute teleconference meetings. Prior to the first meeting, they were asked to rate the importance and face validity of the 40 domains in Table 1. Ratings were made using a 9-point Likert scale ranging from 9 = high validity/importance to 1 = low validity/importance. Numerical criteria were established to determine which domains would be retained, dropped, or forwarded to the panel for discussion. As a result of their rating, 11 domains with a high standard deviation (indicating high discrepancy) were chosen for discussion in the first panel meeting. Panelists were then asked to rate the 11 discussed domains again, and those ratings were used to judge which were retained or dropped.

Between the first and second meeting, panelists were asked to help develop survey items for the domains that were retained, and submit the items to the study team for inclusion. All items had the answer options of “1=Not at all”, “2=A little bit”, “3=Somewhat”, “4=Quite a bit”, and “5=Very much”. For the Peer Services questions, higher scores mean the service is performed to a greater extent. For the implementation factors questions, higher scores means that the factor in question was more favorable to implementation. These items, and some created by study staff, were rated by the panelists on importance on a 7-point Likert scale (ranging from 7 = high importance to 1 = low importance). Using specific criteria, any item that had a low mean importance rating and a high standard deviation was dropped. Twelve items that had high standard deviations for importance (indicating high discrepancy) were brought to the second panel meeting for discussion. Following the meeting, panelists rated these items again, including item revisions suggested at the meeting. The final items were used to create survey measures for peer specialists, supervisors, and Veterans. The expert panel met for a third time after the measure had been pilot tested, and provided feedback on the administration of the measures and initial outcome data.

Pilot study and cognitive interviews

In the Fall 2015, we administered the survey measures to three peer specialists, six Veterans who had received services from those peer specialists (two from each) and three supervisors at a single large VHA medical center. After the survey administration, we then conducted cognitive interviews with the participants to assess their understanding of the measures. The study team chose peer specialists available at the medical center who represented a wide range in experience levels (12, 7.5, and 1.5 years). The peer specialists were asked to choose two Veterans who knew them well and had at least 6 months of time spent together. The supervisors (who were not persons with lived experience of mental illness recovery) varied in their level of involvement with the peer specialists. Two provide only program supervision (focusing on day to day work with clients) and one provides only administrative supervision (focusing on issues of general job performance). As the peer specialist and supervisor surveys were longer (52 survey items for both), we asked these respondents to complete the surveys in advance, no more than 24 hours in advance of their cognitive interview. The Veteran survey has only 21 questions, and Veterans were given unlimited time to complete the survey immediately preceding their cognitive interview.

All cognitive interviews were done in person at the medical center, except one which was done by phone due to disability considerations. Prior to the interview, respondents were asked to complete demographic questions (gender, race, age, education, income source). All respondents were asked to circle any survey items that seemed unclear or concerning, write comments in the margins, and identify any concept they believed was missing.

A researcher (SM) and doctoral student (CMM) together interviewed each individual and audio recorded their responses. Direct probing questions were used to elicit information about the clarity of questions, the formatting of the survey, and the response scales. The probes were scripted; however the two interviewers had expert content knowledge, and often explored a response beyond the scripted probe. Beaty and Willis (2007) suggest this emergent probing is valuable when using investigators to conduct the interviews. After each respondent presented their questions and comments, we asked each about their understanding of up to five additional items that the research team had identified as possibly challenging. Finally, ten more items were chosen at random for discussion. Following this process, we were able to get feedback on nearly all the questions on each survey. At the conclusion, Veterans were given a $25 gift certificate (VHA employees are not permitted to be compensated).

Data analysis

The twelve surveys were coded and descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) were calculated for the peer specialists, Veterans, and supervisors. A subset of 10 items in the peer specialist services area were identified as “Core peer specialist services”—defined as services that every peer specialist should provide regardless of placement, time on job, or the type of Veteran they are helping. Implementation factors were combined across the peer specialist and supervisor respondent types because those items measured organizational level issues.

After transcription of the cognitive interviews, the text was reviewed and organized by item by a doctoral level researcher (KD) naïve to the project. Suggested revisions for the final measure were reviewed by two members of the research team, and then the entire team finalized the changes. Changes suggested by respondents that seemed contradictory or idiosyncratic were either discussed and dismissed by the research team or identified for discussion during the final expert panel meeting.

RESULTS

Fidelity domains identification

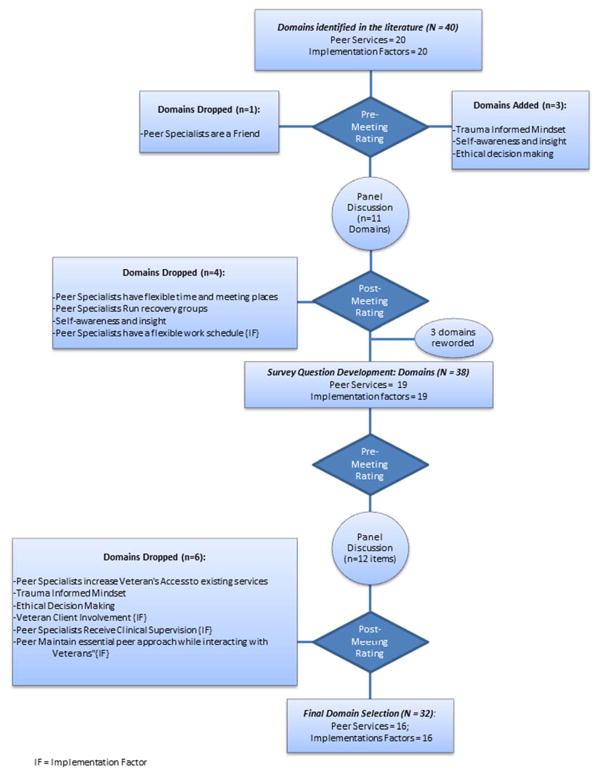

A total of 40 fidelity domains were identified in our literature review, 20 each for peer specialist services and implementation factors (Table 1). Figure 1 shows a flow chart of which domains were dropped and added throughout the meetings of the expert panel. The domains from the literature proved to be robust. Based on the pre-meeting ratings made before the first expert panel discussion, only one of the original domains was dropped. This domain, “peer specialists are a friend” had very low ratings on face validity (M=3.94) and importance (M=4.06) and thus met our criteria for elimination. In addition, three domains were added by expert panel members. Eleven domains showed significant disagreement among panelists (a standard deviation >= 1 indicating high discrepancy), and were discussed at the first expert panel meeting. After the meeting discussion and re-rating process, four domains were dropped. Based on discussion in the second expert panel, an additional six domains (and their corresponding items) were dropped.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the fidelity domains for peer specialist services and implementation factors. IF = implementation factor. see the online article for the color version of this figure.

Using Gill et al. (2009) as a guide, we categorized the final set of domains (see Table 3). The first set (peer specialist activities), overlapping with Gill et al. (2009) Peer support activities, involves various key activities that peer specialists engage in including reducing isolation, focusing on strengths, being a role model and sharing their recovery story, and assisting with illness management. The second set (peer specialist process) generally involves how peer specialists go about their work (e.g., promoting empathy, empowerment, hope, trusting relationships), which is consistent with the Counseling skills and Role of shared experience areas of Gill et al. (2009). The third set, Skill building, overlaps with Skill development from Gill et al. (2009). Two other areas, Documentation and resources had close parallels to similar domains of Gill et al. (2009). Regarding the implementation factors, Gill et al. (2009) overlapped with domains from our measure on professional development issues such as Managing dual roles. The implementation factor domains in our measure also addressed several other areas not found in Gill et al. (2009). including collaboration with non-peer co-workers, having leadership support, and integrating into clinical teams.

Table 3.

Categorization of peer specialist services and implementation factor domains

| Gill et al. | Peer Fidelity Measure |

|---|---|

| Job delineation | Peer fidelity |

Peer Support activities:

|

Peer specialist Activities

|

Counseling skills

|

peer specialist Process

|

| Skill Development |

Skill Building

|

Professional documentation and Communication

|

Documentation

|

| Knowledge of Resources |

Resources

|

Continued Professional role/Competency Development

|

Professional development

|

peer specialists/co-worker collaboration

|

|

Leadership support of peer specialists

|

|

peer specialist integration into treatment teams

|

Cognitive interviews results

Demographically, the participants included 6 women and 6 men, 9 Caucasian and 3 other races, with an average age of 47. The peer specialist supervisors were all female, Master’s level Caucasians who had worked with peer specialists for 2–4 years. The peer specialists had an average of 7 years work experience as a peer specialist.

Overall, respondents stated that the measure was well formatted and easy to complete and understand. They stated that the response scale was clear, fitting and appropriate. No one described the measures as burdensome. Many instances of wording were discussed, and some word choices were critiqued. For example, some Veterans were unclear about the word “foster” in a question asking whether peer specialists “foster” individual strengths of the Veteran. In some cases, it was easy to address these concerns, in others the question was referred to the third expert panel meeting for discussion.

Some Veterans expressed concern that items described activities that they did not work on with their peer specialist, perhaps because the Veteran had other support for those activities or did not need the particular activity. For example, not all Veterans felt they needed their peer specialist to provide them with information about community resources, but at the same time, they felt uneasy rating their peer specialist low on this item. For this reason, several Veterans recommended that a “does not apply” response option be included.

Several other issues were uncovered in the cognitive interviews. It became clear that Veterans rated their own unique experience with their peer specialist, while peer specialists and their supervisors rated peer specialist activity done with all Veterans with whom they served. Another theme identified was that the process by which Veterans were chosen—by the peer specialists—may have influenced the Veteran’s responses. Several Veterans asked their interviewer whether their peer specialist would be informed of their ratings and stated that they may have inflated their ratings so as to not hurt their peer specialist.

Another important finding from the interviews concerned the role of supervisors. At the VA, it is quite common for peer specialists to have an administrative supervisor and a program level supervisor. The survey asked a number of questions that some supervisors simply did not know how to answer. Sometimes the supervisor gave a rating by simply assuming knowledge (e.g., “I know the other supervisor handles this, and I assume it’s done well”) and sometimes they simply skipped the question or marked it for comment.

Survey results

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics for each of the sub groups. Descriptively, peer specialists had higher means than their respective supervisors or Veterans on the peer specialist services items. This suggests that peer specialists rated themselves with a higher level of engagement in various services than their supervisors or Veterans rated them. In particular, the range of the Veterans’ ratings (1.3 to 4.3) was much wider than the supervisors or peer specialists. The means for the Core peer specialist services tended to be higher than means for peer specialist services. For the implementation factor questions, the means of the peer specialists tended to be higher than the supervisors. This suggests peer specialists saw fewer or less challenging implementation problems than their supervisors.

Table 2.

Mean responses for survey question items – all and core╪ peer specialist services and implementation factors

| Peer specialist services1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Peer specialist services | Core peer specialist services╪ (Number of items = 10) | ||

|

| |||

| Respondent Type | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| PS1 | PS1 | 4.68 (0.55) | 5.00 (0.0) |

| Supervisor1 | 3.65 (0.84) | 3.90 (0.74) | |

| Supervisor3 | 3.64 (0.91) | 3.60 (0.84) | |

| Veteran1 | 4.28 (1.16) | 5.00 (0.0) | |

| Veteran2 | 4.34 (0.72) | 4.50 (0.53) | |

|

| |||

| PS2 | PS2 | 4.81 (0.56) | 5.00 (0.0) |

| Supervisor1 | 3.71 (0.90) | 4.30 (0.48) | |

| Supervisor2 | 4.32 (0.70) | 4.70 (0.67) | |

| Veteran3 | 4.10 (0.77) | 4.60 (0.52) | |

| Veteran4 | 2.97 (0.78) | 3.10 (0.57) | |

|

| |||

| PS3 | PS3 | 4.21 (0.99) | 4.30 (0.67) |

| Supervisor1 | 4.16 (0.64) | 4.50 (0.53) | |

| Veteran5 | 1.31 (0.60) | 1.70 (0.82) | |

| Veteran6 | 3.38 (1.24) | 3.50 (1.08) | |

| Implementation factors | |||

|

| |||

| Mean (SD) | |||

|

| |||

| Peer specialists (1, 2, & 3) | 4.43 (0.53) | ||

| Supervisors (1, 2, & 3) | 3.87 (0.69) | ||

All items had the answer options of 1=Not at all, 2=A little bit, 3=Somewhat, 4=Quite a bit, and 5=Very much

Core peer specialist services are a subset of the peer specialist questions that address services that all peer specialists deliver irrespective to placement

DISCUSSION

This paper describes the initial development of a peer specialist fidelity measure for two content areas: services provided by peer specialists and implementation factors that impact their employment. Our initial literature search identified 40 domains, and an expert panel narrowed the number of domains and helped generate and then review survey items. Overall, while more research is needed, the comments from the expert panel and those who completed the measure suggest it helped capture what services peer specialists are expected to deliver and what factors influence their successful implementation. The fact that peer specialists rated themselves quite high on the Peer Services items, markedly higher than their supervisors or the Veterans with whom they worked was consistent with organizational research that shows employees often give themselves better appraisals than their supervisors give them (Jaramillo, Carrillat, & Locander, 2005). These results suggest why more than one source of data is needed to make the best assessments of performance (Donaldson & Grant-Vallone, 2002). The Veterans’ results could be related to our finding in the cognitive interviews that peer specialists were rating their own work more globally, while Veterans were specifically rating their individual interactions with the peer specialists. The higher ratings on the Core peer specialist services could be because these are services that are performed regularly (like the core conditions of therapy put forth by Carl Rogers (1957)), which the other services could be more tied to a particular client or setting. Although no formal validity analyses were conducted, these findings do conform with what is expected, suggesting that the measure may be assessing what it purports to measure.

This discussion section will address the following important issues: specific changes to the measure and its administration, comparisons to recent work defining the peer specialist role, philosophical issues to consider when measuring of peer fidelity, and limitations and future research.

Specific changes to the measure

Although the pilot study participants expressed great enthusiasm for the measure, these results suggest several changes are needed. First, many peer specialists have more than one supervisor who may be familiar with different aspects of a peer specialists’ role. Thus, the final version of the measure for supervisors will need to include a careful skip pattern, so that supervisors can identify items they are not responsible for (e.g. continuing education) and items that do not apply to the work of the peer specialist they are rating (e.g. team questions when the peer specialist is not part of a team).

Second, while the Veterans’ responses provided unique and important contributions to our understanding of the peer specialist’s work, it created several measurement challenges. First, it seems important to randomly select Veterans who have worked with the peer specialist, and specifically ask Veterans to answer the questions without regard to how much they “like” their peer specialist overall. Offering them a chance to give a global rating of the peer specialist and to add comments may help with this issue.

Finally, as opposed to having a single measure used in all settings, items in the measure may need to be tailored to the specific service setting. While the Core peer specialist service items may be useful in all settings, the results here suggest that tailoring the items to better reflect the services actually performed (or expected to be performed) would not only make the ratings more accurate, but also more useful.

Comparisons to recent research on peer specialist work

Table 3 compares our domains and categories with that of another study that used job delineation methodology (Gill et al., 2009). Although wording differs, generally, there is strong overlap between the two efforts, which provides evidence that researchers are beginning to coalesce around the key elements of the role, especially given that these three studies had different vantage points. Because of differences in methodology, each study focused on slightly different aspects of the role; and only our measure specifically identifies broader implementation challenges for peer specialists. Gill et al. (2009) also focus on peer specialists in the VHA, and identify both structural and process elements. That research, as well as our results, shows that working within the structure of a professional health care setting clearly influences the work that VHA peer specialists are able and required to accomplish. Both Gill et al. (2009) and this pilot show that understanding VHA policies and procedures, participating in supervision and providing feedback to coworkers are all elements key to the job role in the VHA.

Philosophical issues regarding the measurement of peer specialist fidelity

Besides the practical challenges of measurement, some in the field question whether the role should be measured at all for fear of what such measurement might do to the nature of the peer support being provided. This pilot yielded no remarks by Veterans, supervisors, or the peer specialists themselves that suggested the measurement would undermine the role. In contrast, all were enthusiastic about use of such a measure. All types of services— including those provided by peer specialists—have aspects that make them helpful. This measure is an attempt to ensure that the helpful aspects of peer specialists are better used. Of course, like any tool, a peer specialist fidelity measure could be misused, for example as a way to punitively monitor performance. However, the tool has great potential to help sort out thorny issues with peer specialists such as their potential overlap in duties with other mental health providers and the use of non-peer staff as supervisors. Using this peer specialist fidelity tool—which includes tasks performed by other mental health providers—could help determine the degree to which peer specialists and other providers overlap and assess the utility of having peer specialists deliver services also delivered by others. Fidelity data from peer specialists supervised by fellow peers and non-peers could be compared to assess the utility of non-peer supervision, another concern stemming from the potential lack of understanding of what it is like to be in recovery. In sum, the availability of a peer specialist fidelity measure, if used appropriately, would make it possible to better understand and address issues related to role definition and performance.

Limitations and future directions

These results are from the early stages of testing the peer specialist fidelity measure and should be interpreted with caution. The results reported here are on a small sample and much more psychometric testing needs to be conducted. Another potential limitation is that all the measures are self-report, which could invite biased responses. Although recording sessions between peer specialists and their clients is a gold standard method of assessing service fidelity, we constructed the measures self-report so they would be easily administered across a large system like the VHA. The fact that three different individuals (peer specialist, supervisor, and client) provide ratings on the same peer specialist guards against self-report bias somewhat. However, to truly understand whether self-report yields unbiased ratings, a larger scale study correlating ratings made from both self-report and audiotaped sessions is needed. Doing so may provide evidence that the accuracy of self-report surveys is adequate.

Conclusion

Peer specialist services have been demonstrated to be a helpful component of services for those with serious mental illnesses. Studies have documented positive outcomes but not tracked service delivery quality, a gap that has made it more difficult to reach consensus on the exact role for peer specialists. After further refinement, this measure of peer specialist fidelity could further crystalize the role as well as aid in research and clinical administration.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the peer specialists, Veterans, and supervisors who participated in the pilot test and cognitive interviews. We would also like to thank Daniel O’Brien-Mazza for providing support for this project. Financial support for the paper was provided by the Department of Veterans’ Affairs. All authors do not have any conflict of interests to report. The contents do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the US Government.

References

- Beaty PC, Willis GB. Research synthesis: the practice of cognitive interviewing. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2007;71(2):287–311. [Google Scholar]

- Bond GR, Becker DR, Drake RE, Vogler KM. A fidelity scale for the Individual Placement and Support model of supported employment. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin. 1997;40:265–284. [Google Scholar]

- Bond GR, Evans L, Salyers MP, Williams J, Kim H. Measurement of Fidelity in Psychiatric Rehabilitation. Mental Health Services Research. 2000a;2(2):75–87. doi: 10.1023/a:1010153020697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond GR, Evans L, Salyers MP, Williams J, Kim HW. Measurement of fidelity in psychiatric rehabilitation. Mental Health Services Research. 2000b;2(2):75–87. doi: 10.1023/a:1010153020697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Century J, Rudnick M, Freeman C. A Framework for Measuring Fidelity of Implementation: A Foundation for Shared Language and Accumulation of Knowledge. American Journal of Evaluation. 2010 doi: 10.1177/1098214010366173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chinman M, George P, Dougherty RH, Daniels AS, Shoma Ghose S, Swift A, Delphin-Rittmon ME. Peer support services for individuals with serious mental illnesses: Assessing the evidence. Psychiatric Services. 2014;65:429–441. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinman M, Lucksted A, Gresen R, Davis M, Losonczy M, Sussner B, Martone L. Early experiences of employing consumer-providers in the VA. Psychiatric Services. 2008;59(11):1315–1321. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.11.1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinman MJ, Kloos B, O’Connel M, Davidson L. Service providers’ views of psychiatric mutual support groups. The Journal of Community Psychology. 2002;30:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Dane AV, Schneider BH. Program integrity in primary and early secondary prevention: are implementation effects out of control? Clinical Psychology Review. 1998;18(1):23–45. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(97)00043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson L, Chinman M, Kloos B, Weingarten R, Stayner D, Tebes JK. Peer Support Among Individuals With Severe Mental Illness: A Review of the Evidence. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 1999;6(2):165–187. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.6.2.165. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson L, Chinman M, Sells D, Rowe M. Peer support among adults with serious mental illness: a report from the field. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2006;32:443–450. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Memorial Fund Q. 1966;44(3 Suppl):166–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson SI, Grant-Vallone EJ. Understanding self-report bias in organizational behavior research. Journal of Business and Psychology. 2002;17(2):245–260. [Google Scholar]

- Doughty C, Tse S. The Effectiveness of Service User-Run or Service User-Led Mental Health Services for People with Mental Illness: A Systematic Literature Review. Wellington, New Zealand: Mental Health Commission; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fuhr DC, Salisbury TT, De Silva MJ, Atif N, van Ginneken N, Rahman A, Patel V. Effectiveness of peer-delivered interventions for severe mental illness and depression on clinical and psychosocial outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The International Journal for Research in Social and Genetic Epidemiology and Mental Health Services. 2014;49(11):1691–1702. doi: 10.1007/s00127-014-0857-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gidugu V, Rogers ES, Harrington S, Maru M, Johnson G, Cohee J, Hinkel J. Individual peer support: a qualitative study of mechanisms of its effectiveness. Community Mental Health Journal. 2015;51(4):445–452. doi: 10.1007/s10597-014-9801-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill K, Murphy A, Burns-Lynch B, Swarbrick M. Delineation of a job role. Journal of Rehabilitation. 2009;75:23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Jaramillo F, Carrillat FA, Locander WB. A meta-analytic comparison of managerial ratings and self-evaluations. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management. 2005;25(4):315–328. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann CL, Schulberg H, Schooler N. Self-help group participation among people with severe mental illness. Prevention in Human Services. Prevention in Human Services. 1994;11:315–331. [Google Scholar]

- Landers GM, Zhou M. An analysis of relationships among peer support, psychiatric hospitalization, and crisis stabilization. Community Mental Health Journal. 2011;47(1):106–112. doi: 10.1007/s10597-009-9218-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Evans B, Mayo-Wilson E, Harrison B, Istead H, Brown E, Pilling S, … Kendall T. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials of peer support for people with severe mental illness. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luke DA, Roberts L, Rappaport J. Individual, group context, and individual-group fit predictors of self-help group attendance. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science. 1993;29:216–238. [Google Scholar]

- McGrew JH, Bond GR, Dietzen L, Salyers M. Measuring the fidelity of implementation of a mental health program model. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62(4):670–678. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.4.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mowbray CT, Holter MC, Teague GB, Bybee D. Fidelity Criteria: Development, Measurement, and Validation. American Journal of Evaluation. 2003;24(3):315–340. doi: 10.1177/109821400302400303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pitt V, Lowe D, Hill S, Prictor M, Hetrick SE, Ryan R, Berends L. Consumer-providers of care for adult clients of statutory mental health services. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebeiro Gruhl KL, LaCarte S, Calixte S. Authentic peer support work: challenges and opportunities for an evolving occupation. Journal of Mental Health. 2015 doi: 10.3109/09638237.2015.1057322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repper J, Carter T. A review of the literature on peer support in mental health services. Journal of Mental Health. 2011;20:392–411. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2011.583947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers C. The neccessary and sufficient conditions for therapeutic personality change. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1957;21:95–103. doi: 10.1037/h0045357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers ES, Farkas M, Anthony WA, Kash M, Maru M. Systematic Review of Peer Delivered Services Literature 1989–2009. Boston, MA: Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation, Boston University; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Salzer MS, Schwenk E, Brusilovskiy E. Certified peer specialist roles and activities: results from a national survey. Psychiatric Services. 2010;61(5):520–523. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.61.5.520. 61/5/520 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA. Core competencies for peer workers in behavioral health services. Bringing recovery supports to scale, technical assistance center strategy. 2015 Retrieved 3/30/2016, from http://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/programs_campaigns/brss_tacs/core-competencies.pdf.

- Simpson EL, House AO. Involving users in the delivery and evaluation of mental health services: systematic review. British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Ed) 2002;325:1265–1268. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7375.1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teague GB, Bond GR, Drake RE. Program fidelity in assertive community treatment: Development and use of a measure. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1998;68(2):216–232. doi: 10.1037/h0080331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright-Berryman JL, McGuire AB, Salyers MP. A review of consumer-provided services on assertive community treatment and intensive case management teams: Implications for future research and practice. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association. 2011;17(1):37–44. doi: 10.1177/1078390310393283. 17/1/37 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]