Abstract

Background

To compare the rate of surgical site infection (SSI) using surgeon versus patient report.

Materials and methods

A prospective observational study of surgical patients in four hospitals within one private health-care system was performed. Surgeon report consisted of contacting the surgeon or staff 30 d after procedure to identify infections. Patient report consisted of telephone contact with the patient and confirmation of infections by a trained surgical clinical reviewer.

Results

Between February 2011 and June 2012, there were 2853 surgical procedures that met inclusion criteria. Surgeon-reported SSI rate was significantly lower (2.4%, P value < 0.01) compared with patient self-report (4.3%). The rate was lower across most infection subtypes (1.3% versus 3.0% superficial, 0.3% versus 0.5% organ/space) except deep incisional, most proceduretypes (2.3% versus 4.4% generalsurgery) exceptplastics, most patient characteristics(except body mass index < 18.5), and all hospitals. There were disagreements in 3.4% of cases; 74 cases reported by patients but not surgeons and 21 cases vice versa. Disagreements were more likely in superficial infections (59.8% versus 1.0%), C-sections (22.7% versus 17.7%), hospital A (22.7% versus 17.7%), age < 65 y (74.2% versus 68.3%), and body mass index ≥ 30 (54.2% versus 39.9%).

Conclusions

Patient report is a more sensitive method of detection of SSI compared with surgeon report, resulting in nearly twice the SSI rate. Fair and consistent ways of identifying SSIs are essential for comparing hospitals and surgeons, locally and nationally.

Keywords: Surgical site infection, Surveillance, Surgeon report, Patient report, Health care–acquired infection, Hospital-acquired condition, Quality improvement, National surgical quality improvement program, National Healthcare Surveillance Network

1. Introduction

Prevention, accurate detection, and treatment of surgical site infections (SSIs) are important for patient safety. Approximately 27 million surgical procedures are performed each year in the United States [1]. Among surgical patients, SSI accounts for about 40% of all hospital-acquired infections [2]. Among patients with SSI, 77% of all deaths are related to the infection [1]. Patients with SSIs incur approximately twice the health-care costs as those without SSIs [3]. The additional cost of managing SSI ranges less than $400 (superficial SSI) to more than $30,000 per case (organ/space SSI) [4], with the potential increased length of hospital stay by 7 d [2].

Reducing the rate of SSI is a priority for quality and safety initiatives in the United States. In 2002, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), in collaboration with the Center for Disease Control (CDC) implemented the Surgical Infection Prevention Project to decrease the morbidity and mortality associated with SSI [5]. In 2003, the CMS and the CDC partnered with a number of other professional organizations nationally in the Surgical Care Improvement Project (SCIP) [5,6]. The SCIP focuses on measurement of quality in four broad areas in which the incidence and cost of surgical complications is high: prevention of SSI, venous thromboembolism, adverse cardiac events, and respiratory complications [5,6].

For a variety of reasons, knowing the true SSI rate is important. Surrogates for SSI such as SCIP process measures do not correlate well with surgical outcomes [7–9]. SSI data are essential to quality improvement efforts [10]. Hospital reputation and prestige are tied to these rates because they are publicly reported as part of CMS’s Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting Program [11]. Hospitals are compensated based on SSI rates as part of pay-for-performance programs such as the CMS’s Hospital Value-Based Purchasing program [12].

There are concerns that different sources of clinical data (e.g., medical record review, patient report, or surgeon report) may yield different SSI rates [13–18]. A recent review comparing the CDC-National Healthcare Surveillance Network (CDC/NHSN) and the American College of Surgeons–National Surgical Quality Improvement Project (ACS-NSQIP) found an average 8.3% difference in SSI rates within the same hospitals [19]. Despite this potential source of variability, the CDC/NHSN program allows for significant variability and discretion in the surveillance methodology used to determine the SSI rate. These biases call into question the validity of the data when comparing SSI rates across health-care facilities.

The purpose of this study was to identify the difference in SSI rates achieved through patient report versus surgeon report. We hypothesize that patient report is a more sensitive source for identifying SSIs.

2. Methods

This study was approved by the institutional review board of the Hawaii Pacific Health System.

2.1. Study design and population

We performed a prospective observational study between February 2011 and June 2012 of the SSI rate within one health-care system consisting of four hospitals in the state of Hawaii: A specialty women/children’s 207 bed hospital with approximately 17,000 admissions/y, 7500 surgical cases/y, a case mix index (CMI) of 0.93, approximately 600 physicians, and 69 private–practice surgeons (hospital A). A suburban community 126 bed-hospital with approximately 6500 admissions/y, 7500 surgical cases/y, a CMI of 1.57, 400 private-practice physicians, and 24 private–practice surgeons (hospital B). An urban tertiary care 159 bed-hospital with approximately 7500 admissions/y, 5000 surgical cases/y, a CMI of 1.80, 350 employed physicians, and 22 employed surgeons (hospital C). A rural 72 bed-hospital with approximately 4000 admissions/y, 6000 surgical cases/y, a CMI of 1.10, 192 physicians (private–practice and employed), and 12 employed surgeons (hospital D). Data collection for hospital D ended on May 2012. Hospitals A and C are affiliated with a medical school.

2.2. Identification of surgical cases

All surgical cases performed were identified by methodologies outlined by CDC/NHSN and the American College of Surgeons–National Surgical Quality Improvement Project (ACS-NSQIP) [20,21]. SSI surveillance is one patient safety metric reported to the CDC/NHSN. Surgical cases are identified by International Classification of Diseases–9 procedure codes provided by CDC/NHSN [22]. ACS-NSQIP is an open subscription nationally validated surgical outcomes database. Surgical cases are identified by Current Procedural Terminology codes [20]. Eight of the 10 surgical subspecialties from the ACS-NSQIP “Essentials” program were included (i.e., general surgery, vascular surgery, orthopedic surgery, otolaryngology, plastic surgery, gynecologic surgery, neurosurgery, and urology) [21]. Cardiac and thoracic surgery cases were excluded because they are followed through the Society for Thoracic Surgery National Database. Cesarean sections (C-sections) were included in addition to the eight surgical specialties. ACS-NSQIP identifies cases by a sampling methodology where a trained surgical reviewer [23] abstracts data on an 8-d cycle that allows for case selection with equal representation [20,21]. High-volume, low-risk procedures are limited in this sampling methodology [20,21].

2.3. Definition of SSI

SSI was classified according to the CDC/NHSN or ACS-NSQIP definition as an infection that develops within 30 d after an operation or within 1 y if an implant was placed and the infection seems to be related to the surgery (Appendix 1) [24]. Although both definitions are essentially identical, they varied in the surveillance methodology. SSIs are classified as being either superficial, deep space, or organ/space. Superficial infections involve only the skin and subcutaneous tissue. Deep space infections involve the deeper soft tissues of the incision. Organ/space infections involve any part of the organ or space other than the incised body wall layers that are opened or manipulated during the operation.

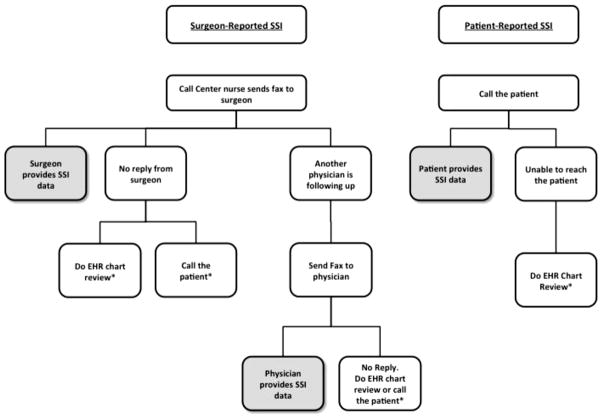

2.4. Surgeon-reported SSI

Surgeons or their staff were sent a monthly list of procedures fulfilling CDC/NHSN criteria that they had performed in the preceding month (Fig. 1). All qualifying procedures were included. Surgeons were asked to review the list and identify and provide details for patients that had experienced an SSI. CDC/NHSN criteria for the diagnosis of SSI were included on every form. Surgeons were free to use any source of data available to them to recall whether their patients had had an infection. If the list was not returned, staff followed up with the surgeon’s office until the information was received. There were a small number (10 of 134) of surgeons who elected not to participate; their procedures were excluded from the study. In a small percentage of procedures, the surgeon did not respond (<10%); these procedures were excluded.

Fig. 1.

Algorithm for surgeon- and patient-reported SSI surveillance. * Cases excluded from the study. EHR = electronic health record; SSI = surgical site infections.

2.5. Patient-reported SSI

The call center was provided with a list of surgical cases fulfilling ACS/NSQIP criteria and all cesarian section cases. Call center staff made at least three attempts to reach all patients by telephone once 30 d had passed since the procedure. A standard script was used to inquire about recovery with a focused set of questions to identify SSIs (Appendix 2). All patient-reported SSIs were reviewed and confirmed by a trained surgical clinical reviewer using NSQIP criteria for SSI; the trained surgical clinical reviewer also classified the severity of the SSI. Among the four sites, patient follow-up was achieved in 86%–97% of the time. Patients who were unable to be reached were excluded from the study.

2.6. Data collection

We collected data on SSI rates: superficial incisional, deep incisional, and organ/space. We measured readmission rates within 30 d, both to the same facility where they had surgery and to another facility within the system. All-cause readmission was determined by electronic medical record review. We measured how many had wound culture data available. The following patient characteristics were collected: age, gender, and body mass index (BMI). Diabetes Mellitus (DM) status was unavailable for C-section patients. Only surgical cases with data available from both surgeon and patient self-report were included in this analysis. Surgical cases were excluded if: (1) the surgeon elected not to participate, (2) the surgeon did not reply to the self-report, or (3) the patient could not be contacted.

2.7. Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SAS software version 9.3 (Cary, NC). SSI rates were summarized using proportions. Subgroup analyses were performed comparing SSI type (superficial incisional, deep incisional space, organ/space), procedure types, hospital, and all-cause readmission status. To evaluate the effect of the surgeon report versus patient report on different characteristics, age was divided into two groups (>65 y and <65 y), BMI was divided into four categories using CDC definitions (<18.5 [underweight], 18.5–24.9 [normal weight], 25–29.9 [overweight], ≥30 [obese]) [25]. To compare differences in the SSI rate, the chi-square test was used. If appropriate, Fisher’s exact test was used.

3. Results

Over the study period, 2853 cases performed by 125 surgeons meeting inclusion criteria were identified (Table 1). The largest subset of cases was general surgery (46%). Hospital B provided the most cases (41%). There were slightly more females compared with males (64.7%). The average BMI of the patients was 29.5 ± 7.4 kg/m2.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and distribution of surgical procedures.

| Characteristic | n = 2853, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Surgical procedure | |

| C-section | 509 (17.8) |

| General surgery | 1306 (45.8) |

| Gynecology | 19 (0.7) |

| Neurosurgery | 96 (3.4) |

| Orthopedics | 777 (27.2) |

| Otolaryngology | 19 (0.7) |

| Plastics | 34 (1.2) |

| Urology | 42 (1.5) |

| Vascular | 51 (1.8) |

| Hospital | |

| A | 509 (17.8) |

| B | 1170 (41.0) |

| C | 1048 (36.7) |

| D | 126 (4.4) |

| Patient | |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 54.1 ± 19.0 |

| Female | 1844 (64.7) |

| BMI (mean ± SD) | 29.5 ± 7.4 |

| Race | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 7 (0.3) |

| Asian | 1292 (45.3) |

| Black or African American | 35 (1.2) |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 569 (20.0) |

| White | 746 (26.2) |

| Unknown/Not reported | 204 (7.2) |

| Smoker | |

| Yes | 359 (12.6) |

| No | 2463(86.3) |

| Unknown/Not reported | 31 (1.1) |

| Diabetes | |

| Insulin dependent | 108 (3.8) |

| Non-insulin dependent | 259 (9.1) |

| No | 1946 (68.2) |

| Unknown/Not reported | 540 (18.9) |

| ASA classification | |

| ASA 1—Normal healthy | 162 (5.7) |

| ASA 2—Mild systemic disease | 1596 (55.9) |

| ASA 3—Severe systemic disease | 995 (34.9) |

| ASA 4—Severe systemic disease that is a constant threat to life | 61 (2.1) |

| ASA 5—Moribund and not expected to survive without operation | 7 (0.3) |

| Unknown/Not reported | 32 (1.1) |

ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists; SD = standard deviation.

All values are reported as a number and percent of total unless otherwise indicated.

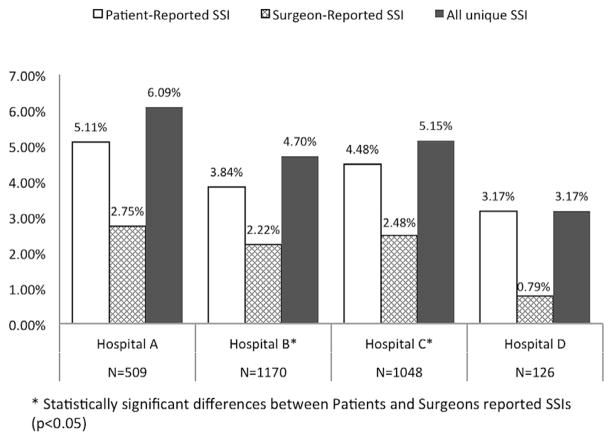

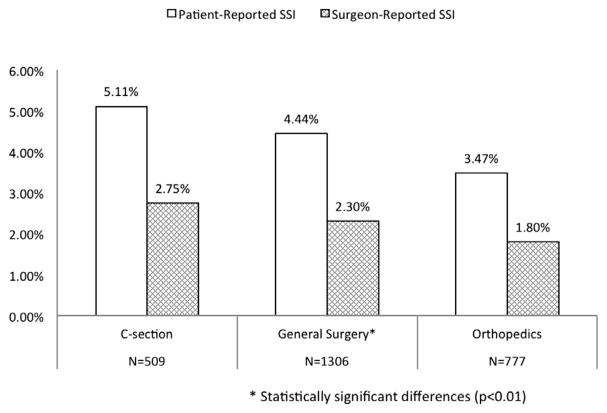

In aggregating the rate among all hospitals, the surgeon-reported SSI rate was 2.4%, whereas the patient-reported SSI rate was 4.3%, P < 0.01 (Table 2). The rate was higher for patient-reported SSI across all infection types except deep incisional SSI (Table 2). The P value for superficial SSI was <0.0001; the P value for combined deep incisional and organ/space SSI was 0.70 (not shown in table). The rate was higher for patient-reported SSI across all hospitals (Fig. 2, P values varied). The rate was the same or higher for patient-reported SSI across all surgical procedure types except plastics (Fig. 3, P values varied). The SSI rate was the same (BMI < 18.5) or higher for patient-reported SSI across all patient characteristics: age, gender, BMI, readmission status (P values varied). Of the 26 readmitted patients, 22 were readmitted for an SSI. Of these 22, both patient- and surgeon-report detected 13 cases. Six were detected only by patient report; three only by surgeon report.

Table 2.

SSI rate by surveillance method.

| Characteristic | Surgeon-reported SSI n = 2853, n (%) |

Patient-reported SSI n = 2853, n (%) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 67 (2.4) | 122 (4.3) | <0.01 |

| Superficial incisional | 36 (1.3) | 86 (3.0) | <0.01 |

| Deep incisional | 20 (0.7) | 16 (0.6) | |

| Organ/space | 8 (0.3) | 15 (0.5) | |

| Unknown | 3 (0.1) | 5 (0.2) | |

| No SSI | 2786 (97.7) | 2731 (95.7) | |

| Surgical procedure | |||

| C-section | 14 (2.8) | 26 (5.1) | 0.07 |

| General surgery | 30 (2.3) | 58 (4.4) | <0.01 |

| Gynecology | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1.0 |

| Neurosurgery | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.0) | 1.0 |

| Orthopedics | 14 (1.8) | 27 (3.5) | 0.06 |

| Otolaryngology | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1.0 |

| Plastics | 4 (11.8) | 6 (17.7) | 0.73 |

| Urology | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1.0 |

| Vascular | 4 (7.8) | 4 (7.8) | 1.0 |

| Hospital | |||

| A | 14 (2.8) | 26 (5.1) | 0.08 |

| B | 26 (2.2) | 45 (3.8) | 0.03 |

| C | 26 (2.5) | 47 (4.5) | 0.02 |

| D | 1 (0.8) | 4 (3.2) | 0.37 |

| Patient characteristics | |||

| Age | |||

| <65 y (n = 1954) | 53 (2.7) | 89 (4.6) | <0.01 |

| ≥65 y (n = 899) | 14 (1.6) | 33 (3.7) | <0.01 |

| Gender | |||

| Female (n = 1844) | 42 (2.3) | 76 (4.1) | <0.01 |

| Male (n = 1006) | 25 (2.5) | 46 (4.6) | 0.02 |

| BMI | |||

| <18.5 (n = 74) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.4) | 1.00 |

| 18.5–24.9 (n = 726) | 9 (1.4) | 27 (3.7) | <0.01 |

| 25–29.9 (n = 874) | 18 (2.1) | 28 (3.2) | 0.18 |

| ≥30 (n = 1132) | 38 (3.4) | 64 (5.7) | 0.01 |

| Readmission status (all-cause) | |||

| Readmitted (n = 26) | 16 (61.5) | 19 (73.1) | 0.56 |

| Not readmitted (n = 2827) | 51 (1.8) | 103 (3.6) | <0.01 |

All values are reported as a number and percent of total unless otherwise indicated.

Bold values indicates the primary outcome.

Fig. 2.

Variation of surgical site infection (SSI) rates by site.

Fig. 3.

Variation in surgical site infection (SSI) rate by surgery type (Top 3).

Patients reported 122 SSIs, of which 46 (38%) were reported by the surgeon, and 76 (62%) were reported as no SSI by the surgeon. Surgeons reported 67 SSIs, of which 46 (69%) were reported by the patient, and 21 (31%) were not. Overall, there was concordance in 96.6% of cases (46 true positives + 2710 true negatives of 2853 cases) and discordance in 3.4% (76 + 21 of 2854 cases) of reported SSI cases (Table 3). Cases where there were disagreements between patient and surgeon report were more likely to be superficial incisional infections (59.8% versus 1.0%), to be C-section surgical procedures (22.7% versus 17.7%), have occurred at hospital A (22.7% versus 17.7%), be in patients aged <65 y (74.2% versus 68.3%), and be in patients with BMI ≥ 30 (54.2% versus 39.9%; Table 4). Ten organ/space SSIs were reported by patients but not identified by the surgeon.

Table 3.

Cross tabulation between surgeon- and patient-reported SSI, by infection type.

| Surgeon-reported | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Infection type | None | Superficial incisional | Deep incisional | Organ/space | Not specified | Total | |

| Patient-reported | None | 2710 | 11 | 6 | 4 | 0 | 2731 |

| Superficial incisional | 58 | 23 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 86 | |

| Deep incisional | 3 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 16 | |

| Organ/space | 10 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 15 | |

| Not specified | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | |

| Total | 2786 | 36 | 20 | 8 | 3 | 2853 | |

Table 4.

Comparison between discordant and concordant cases of SSIs as reported by patients and surgeons.

| Characteristic | Agreement (concordance) between patient and surgeon reports* n = 2756, n (%) |

Disagreement (discordance) between patient and surgeon-report* n = 97, n (%) |

Patient report but not surgeon report n = 76, n (%) |

Surgeon report, but not patient report n = 21, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infection type†/‡ | ||||

| Superficial incisional | 28 (1.0) | 58 (59.8) | 58 (76.3) | 11 (52.4) |

| Deep incisional | 13 (0.5) | 3 (3.1) | 3 (4.0) | 6 (28.6) |

| Organ/space | 5 (0.2) | 10 (10.3) | 10 (13.2) | 4 (19.0) |

| Unknown | 0 (0) | 5 (5.2) | 5 (6.6) | 0 |

| No SSI | 2710 (98.3) | 21 (21.7) | — | — |

| Surgical procedure† | ||||

| C-section | 487 (17.7) | 22 (22.7) | 17 (22.4) | 5 (23.8) |

| General surgery | 1262 (45.8) | 44 (45.4) | 36 (47.4) | 8 (38.1) |

| Gynecology | 19 (0.7) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 |

| Neurosurgery | 96 (3.5) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 |

| Orthopedics | 754 (27.4) | 23 (23.7) | 18 (23.7) | 5 (23.8) |

| Otolaryngology | 19 (0.7) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 |

| Plastics | 30 (1.1) | 4 (4.1) | 3 (4.0) | 1 (4.8) |

| Urology | 42 (1.5) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 |

| Vascular | 47 (1.7) | 4 (4.1) | 2 (2.6) | 2 (9.5) |

| Hospital† | ||||

| A | 487 (17.7) | 22 (22.7) | 17 (22.4) | 5 (23.8) |

| B | 1133 (41.1) | 37 (38.1) | 28 (36.8) | 9 (42.9) |

| C | 1013 (36.8) | 35 (36.1) | 28 (36.8) | 7 (33.3) |

| D | 123 (4.5) | 3 (3.1) | 3(4.0) | 0 |

| Patient characteristics | ||||

| Age | ||||

| <65 y (n = 1954) | 1882 (68.3) | 72 (74.2) | 84 (71.1) | 18 (85.7) |

| ≥65 y (n = 899) | 874 (31.7) | 25 (25.8) | 22 (29.0) | 3 (14.3) |

| Gender | ||||

| Female (n = 1844) | 1780 (64.7) | 64 (66.0) | 49 (64.5) | 15 (71.4) |

| Male (n = 1006) | 973 (35.3) | 33 (34.0) | 27 (35.5) | 6 (28.6) |

| BMI† | ||||

| <18.5 (n = 74) | 72 (2.7) | 2 (2.1) | 1 (1.3) | 1 (4.8) |

| 18.5–24.9 (n = 726) | 704 (26.0) | 22 (22.9) | 20 (26.7) | 2 (9.5) |

| 25–29.9 (n = 874) | 854 (31.5) | 20 (20.8) | 15 (20.0) | 5 (23.8 |

| ≥30 (n = 1132) | 1080 (39.9) | 52 (54.2) | 39 (52.0) | 13 (61.9) |

| Readmission status (all-cause) | ||||

| Readmitted (n = 26) | 24 (0.9) | 2 (2.1) | 1 (1.3) | 1 (4.8) |

| Not readmitted (n = 2827) | 2732 (99.1) | 95 (97.9) | 75 (98.7) | 20 (95.2) |

All values are reported as a number and percent of column unless otherwise indicated.

Patient-report classification of surgical site infection type used in description because these were more complete (more cases).

P value <0.05 comparing agreement versus disagreement cases.

Concordance/discordance based on whether an infection occurred only, not classification of infection type. Concordance/discordance of classification type is found on Table 3.

4. Discussion

In this study, we found significant differences in the SSI rate obtained between surgeon- and patient-reported surveillance methodologies. Patient report resulted in nearly twice the SSI rate (4.3%) compared with surgeon report (2.4%). Neither surveillance method identified all SSIs.

A valid and reliable method of identifying the SSI rate has not been identified [26]. There is a strong need in health care for good surveillance systems in assessing complications of medical care. These systems need to be accurate and consistent. They need to be efficient in terms of time required to collect the data, personnel required to collect the data, and lack of redundancy from alternative systems. Data from these systems should be timely, so that they can inform care [10].

There are a variety of surveillance methodologies and systems for determining the rate of SSI. Administrative (billing) data can capture billing codes for SSI but relies on accurate coding of the discharge diagnoses and historically has been insensitive [27–29]. They do not capture most of the infections, which occur after hospital discharge, and appear to be a poor tool for SSI identification and surveillance [27,30,31]. When compared to CDC/NHSN SSI surveillance methods, the positive predictive value of using administrative data to identify SSI varies between 14% and 51% [27]. Surveillance methods using clinical data (e.g., medical record review, patient report, or surgeon report) are generally viewed as more accurate than administrative data [28].

These results underscore the difficulties in creation of an optimal surveillance system for detection of SSI. Care was taken to strictly adhere to both NHSN/NSQIP methodologies for detection and diagnosis of SSI. Yet both systems allow flexibility in the surveillance mechanism for detection of SSI. NHSN requires clinical surveillance for SSI but does not mandate the particular methodology to be used for surveillance. This means that the SSI rates reported by a facility may reflect patients who had a readmission, a documentation of a SSI in the health records (surgeon’s outpatient record, hospital record, or any other physician’s record), a surgical wound culture that grew a potential pathogen or any combinations of these methods. NSQIP requires active surveillance at 30 d after operation. This surveillance can be accomplished through health records review (surgeon’s outpatient record, hospital record clinic chart, or the patient’s complete medical record), a letter to the patient, or a phone call to the patient.

Although this flexibility helps different institutions match data collection with their available resources, our results suggest that the variation in the surveillance methodology is important. This variation in surveillance methodology was of significant concern to our surgeons. Moreover, both NHSN and NSQIP can be “gamed” to limit detection of SSI. For example, organizations might use the least sensitive method of SSI detection to minimize SSI rates instead of the most sensitive methods to learn from the events. This is especially important when the stakes are high, for example, in the case of public reporting or pay for performance.

With institution of the patient-reported program, we have experienced a significant improvement in trust of SSI data, particularly with surgeons. Within our health-care system, we had an internally driven interest in the outcomes of surgical patients. To assess SSI, we asked surgeons to provide information on the post-hospital outcome of their patients. Attempts to use these data to engage surgeons in quality improvement processes were repeatedly met with lack of interest due to concerns about data accuracy. A predominant concern was: “I report all my SSIs accurately in my monthly report, but I do not think those other surgeons do,” and this quickly moved to a dismissal of all further discussion. Quality improvement teams no longer have discussion about data validity; they have discussions about what others have done to reduce SSIs (and other postoperative complications), quickly followed by “so what will we do?” Accurate data have also allowed sharing of surgeon-specific SSI rates. Once a fair and consistent way of identifying SSIs was established, surgeons were comfortable comparing themselves to others, both nationally and locally.

We were somewhat surprised to find that neither the surgeon-reported nor the patient-reported SSI rate painted a complete picture. Surgeons were, at times, surprised to know that their patients had a diagnosis of SSI. This did not seem to vary by whether the surgeon was employed or was in independent practice (subjective perception). In some cases, patients were diagnosed by their primary care providers, other cases were diagnosed in the emergency department. In conversations with our surgeons, there was concern that SSI was being overdiagnosed and treated by other physicians caring for their patients. In other cases, surgeons did not consistently apply CDC definitions of SSI, although they were provided this information. Patient-reported SSI did not paint a complete picture either because patients sometimes forgot that they had had an infection in the grand scheme of their surgical course. Moreover, sometimes the nonmedical perspective made it difficult for them to even know that they had an infection.

The number of organ/space SSIs and SSIs among readmitted patients who were not identified by the surgeon was unexpected. We expected to find few differences for these severe SSIs because organ/space SSIs often require hospital admission for treatment. Although we assumed surgeons would have a greater awareness of these cases, perhaps they did not recall these cases. Alternatively, surgeons may not have consistently applied the CDC/NHSN SSI definition for these cases. Inconsistent use of CDC/NHSN SSI definitions can result in up to 16% variability in the SSI rate [13].

We found that to have timely, accurate, and reliable SSI rates, (ideal characteristics for quality improvement work), a system had to be set up. Such a system should use individuals with expertise in both patient engagement and SSI surveillance. Using the call center expertise, reliably providing the surgical patient list, and setting up a time table for the calls to occur as soon as the 30-d postoperative period had elapsed was all necessary for the system to work. Good communication between the call center staff, the surgical review nurses, and the hospital quality and infection prevention staff was important. It made it possible to initiate surgical process improvements more promptly for cases where concerns were identified.

For the purposes of quality improvement, we suggest that hospitals use surveillance methods that are most sensitive and reliable at detection of SSIs to identify and learn from these events. Hospitals should consider incorporating patient report as part of that surveillance system. Unfortunately, this approach can inadvertently penalize hospitals in public reporting of SSIs and comparisons between hospitals. Policy makers should identify consistent and reliable surveillance methods so that they more closely align with quality improvement goals.

4.1. Potential limitations

There are several potential limitations to this study. First, the differences between surgeon- and patient-reported SSI rates may be due to differences in the NHSN and NSQIP definition of an SSI. The surgeon-reported rate is based on the NHSN definition, whereas the patient-reported rate is based on NSQIP definition. Although efforts have been taken to “harmonize” these definitions [32], a recent study still found significant differences in SSI rates between the two systems. Some of this discrepancy was due to differences in case selection associated with the two methods. Our present study, overcomes this by comparing SSI rates using the same patients. Second, the SSI rate from patient report is limited by patient recall and medical knowledge. This is an inherent limitation of this methodology. In some cases, patients did not know they had or were being treated for an infection. However, we limited this bias by having a standard script to query for possible infections and involving surgical clinical reviewers to review all potential cases. Third, patient-reported SSI surveillance with telephone encounters may not be feasible in all health-care settings given the resources required. However, we found the accurate data, and its implications far outweighed the additional costs required.

5. Conclusion

We found variability in the SSI rate obtained through surgeon-versus patient-reported surveillance methodology. Patient-reported surveillance was a more sensitive method of determining SSI than surgeon-reported methods and resulted in nearly twice the SSI rate. Neither method captured all cases of SSI. Current national SSI surveillance programs, such as NHSN, allow for both methods of data collection. This may lead to unintended bias in comparing SSI rates across organizations locally and nationally.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Johns Hopkins University Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality (AI) team for direction and guidance as part of the CUSP for Safe Surgery (SUSP) Project: Sean M. Berenholtz, MD, MHS; Charles Bosk, PhD; Patricia Francis, MS, MA, PMP; Vipra Ghimire, MPH; Ksenia Gorbenko, PhD; Christine A. Goeschel, ScD, MPA, MPS, RN, FAAN; Erin Hanahan, MPH; Valerie Hartman, MS; Deborah B. Hobson, RN, BSN; Lisa H. Lubomski, PhD; Martin A. Makary, MD, MPH; Lisa L. Maragakis, MD, MPH; Mohd Nasir Mohd Ishmail, MSc, PhD(c); Julius Cuong Pham, MD, PhD; Peter J. Pronovost, MD, PhD; Dianne Rees, MA, PhD, JD; Michael Rosen, PhD; Kathryn Taylor, RN, MPH; Mary Twomley, MS, PMP; Laura Vail, MS; Catherine van de Ruit, PhD; Sallie J. Weaver, PhD; Kristina Weeks, MHS, PhD(c); Elizabeth Wick, MD, FACS; Bradford D. Winters, MD, PhD.

J.C.P. is supported, in part, by a contract from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality as part of the CUSP for Safe Surgery (SUSP) Project (HHSA29032001T).

D.M.L. is supported, in part, by a contract from the Hawaii Medical Service Association as part of the Hawaii Safer Care Project.

Authors’ contributions: J.C.P., M.J.A., and D.M.L. contributed to study conception and design and drafting of the article; M.J.A. and C.K. contributed to acquisition of data; all the authors contributed to analysis and interpretation of data and critical revision of the article.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2015.12.039.

References

- 1.Mangram AJ, Horan TC, Pearson ML, Silver LC, Jarvis WR. Guideline for prevention of surgical site infection, 1999. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Am J Infect Control. 1999;27:97. quiz 133–134; discussion 196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones RS, Brown C, Opelka F. Surgeon compensation: “Pay for performance,” the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program, the Surgical Care Improvement Program, and other considerations. Surgery. 2005;138:829. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Broex EC, van Asselt AD, Bruggeman CA, van Tiel FH. Surgical siteinfections: how higharethecosts? J HospInfect. 2009;72:193. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2009.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Urban JA. Cost analysis of surgical site infections. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2006;7(Suppl 1):S19. doi: 10.1089/sur.2006.7.s1-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bratzler DW, Hunt DR. The surgical infection prevention and surgical care improvement projects: national initiatives to improve outcomes for patients having surgery. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:322. doi: 10.1086/505220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fry DE. Surgical site infections and the surgical care improvement project (SCIP): evolution of national quality measures. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2008;9:579. doi: 10.1089/sur.2008.9951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.LaPar DJ, Isbell JM, Kern JA, Ailawadi G, Kron IL. Surgical Care Improvement Project measure for postoperative glucose control should not be used as a measure of quality after cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;147:1041. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rasouli MR, Jaberi MM, Hozack WJ, Parvizi J, Rothman RH. Surgical care improvement project (SCIP): has its mission succeeded? J Arthroplasty. 2013;28:1072. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tillman M, Wehbe-Janek H, Hodges B, Smythe WR, Papaconstantinou HT. Surgical care improvement project and surgical site infections: can integration in the surgical safety checklist improve quality performance and clinical outcomes? J Surg Res. 2013;184:150. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2013.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pham JC, Frick KD, Pronovost PJ. Why don’t we know whether care is safe? Am J Med Qual. 2013;28:457. doi: 10.1177/1062860613479397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.CDC; Operational guidance for reporting surgical site infection (SSI) data to CDC’s NHN for the purpose of fulfilling CMS’s hospital inpatient quality Reporting (IQR) Program Requirements. Control CfD, editor. 2012 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/PDFs/FINAL-ACH-SSI-Guidance.pdf.

- 12.CMS. Fact sheets: CMS to improve quality of care during hospital inpatient stays. Baltimore, Maryland: CMS; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor G, McKenzie M, Kirkland T, Wiens R. Effect of surgeon’s diagnosis on surgical wound infection rates. Am J Infect Control. 1990;18:295. doi: 10.1016/0196-6553(90)90228-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitchell DH, Swift G, Gilbert GL. Surgical wound infection surveillance: the importance of infections that develop after hospital discharge. Aust N Z J Surg. 1999;69:117. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1622.1999.01500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whitby M, McLaws ML, Collopy B, et al. Post-discharge surveillance: can patients reliably diagnose surgical wound infections? J Hosp Infect. 2002;52:155. doi: 10.1053/jhin.2002.1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koch CG, Li L, Hixson E, Tang A, Phillips S, Henderson JM. What are the real rates of postoperative complications: elucidating inconsistencies between administrative and clinical data sources. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;214:798. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shahian DM, Silverstein T, Lovett AF, Wolf RE, Normand SL. Comparison of clinical and administrative data sources for hospital coronary artery bypass graft surgery report cards. Circulation. 2007;115:1518. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.633008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cima RR, Lackore KA, Nehring SA, et al. How best to measure surgical quality? Comparison of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Patient Safety Indicators (AHRQ-PSI) and the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP) postoperative adverse events at a single institution. Surgery. 2011;150:943. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2011.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ju MH, Ko CY, Hall BL, Bosk CL, Bilimoria KY, Wick EC. A comparison of 2 surgical site infection monitoring systems. JAMA Surg. 2015;150:51. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.2891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.ACS. [Accessed October 6, 2014];ACS-NSQIP: inclusion/exclusion criteria. 2014 Available from: http://site.acsnsqip.org/program-specifics/inclusionexclusion-criteria-4/

- 21.ACS. [Accessed October 6, 2014];ACS-NSQIP: program options. 2014 Available from: http://site.acsnsqip.org/program-specifics/program-options/

- 22.CDC. [Accessed October 3, 2014];NHSN operative procedure categories (ICD-9-CM codes) 2010 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/PDFs/OperativeProcedures.pdf.

- 23.ACS. [Accessed October 7, 2014];ACS-NSQIP: surgical clinical reviewer training and resources. 2014 Available from: http://site.acsnsqip.org/program-specifics/scr-training-and-resources/

- 24.Horan TC, Andrus M, Dudeck MA. CDC/NHSN surveillance definition of health care-associated infection and criteria for specific types of infections in the acute care setting. Am J Infect Control. 2008;36:309. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.CDC. [Accessed September 29, 2014];Defining overweight and obesity. 2012 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/adult/defining.html.

- 26.Petherick ES, Dalton JE, Moore PJ, Cullum N. Methods for identifying surgical wound infection after discharge from hospital: a systematic review. BMC Infect Dis. 2006;6:170. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-6-170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stevenson KB, Khan Y, Dickman J, et al. Administrative coding data, compared with CDC/NHSN criteria, are poor indicators of health care-associated infections. Am J Infect Control. 2008;36:155. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steinberg SM, Popa MR, Michalek JA, Bethel MJ, Ellison EC. Comparison of risk adjustment methodologies in surgical quality improvement. Surgery. 2008;144:662. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2008.06.010. discussion 662–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Best WR, Khuri SF, Phelan M, et al. Identifying patient preoperative risk factors and postoperative adverse events in administrative databases: results from the Department of Veterans Affairs National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. J Am Coll Surg. 2002;194:257. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(01)01183-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McKibben L, Horan TC, Tokars JI, et al. Guidance on public reporting of healthcare-associated infections: recommendations of the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2005;26:580. doi: 10.1086/502585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Astagneau P, L’Heriteau F. Surveillance of surgical-site infections: impact on quality of care and reporting dilemmas. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2010;23:306. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32833ae7e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Forum NQ. [Accessed November 2, 2014];Endorsement summary: patient safety measures. 2012 Available from: http://www.qualityforum.org/News_And_Resources/Press_Releases/2012/NQF_Endorses_Patient_Safety_Measures.aspx.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.