Abstract

Essential hypertension (EH) and its complications have had a severe impact on public health. However, the underlying mechanisms of the pathogenesis of EH remain largely unknown. Recent investigations, predominantly in rats and mice, have provided evidence that dysregulation of distinct functions of T lymphocyte subsets is a potentially important mechanism in the pathogenesis of hypertension. We critically reviewed recent findings and propose an alternative explanation on the understanding of dysfunctional T lymphocyte subsets in the pathogenesis of hypertension. The hypothesis is that hypertensive stimuli, directly and indirectly, increase local IL-6 levels in the cardiovascular system and kidney, which may promote peripheral imbalance in the differentiation and ratio of Th17 and T regulatory cells. This results in increased IL-17 and decreased IL-10 in perivascular adipose tissue and adventitia contributing to the development of hypertension in experimental animal models. Further investigation in the field is warranted to inform new translational advances that will promote to understand the pathogenesis of EH and develop novel approaches to prevent and treat EH.

Keywords: Hypertension, Interleukin-6, T lymphocyte subsets, T regulatory cells, Th17 cells

Introduction

Essential hypertension (EH) is a common complex trait resulting from the interaction of genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors with aging [1]. Worldwide, about 20 % of adults (~1 billion people) suffer from hypertension, defined as blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg [2]. More than 95 % of hypertensive patients have hypertension of unknown origin, called EH, and most of them display no symptoms [1]. Once a patient is diagnosed with EH, lifelong treatment is usually required [1]. These characteristics lead to a high prevalence of poor control of hypertension. More than half of hypertensive patients under treatment do not achieve the target levels of blood pressure control recommended by current guidelines [3]. Sustained uncontrolled high blood pressure results in target organ damage, including the kidney, brain, and heart. EH has been clearly documented as a major risk factor for myocardial infarction, heart failure, stroke, and renal failure, contributing to more than 7 million deaths annually [2].

During the past few decades, significant progress has been made in our understanding of the pathogenesis of EH. We have long known that short- and long-term blood pressure regulation involves the integrated actions of renal, neural, endocrine, and vascular control systems. Blood pressure can be elevated in the short term by enhanced intrarenal or extrarenal factors that lead to reduced glomerular filtration rate or increased renal tubular reabsorption of salt and water; excessive activation of the sympathetic nervous system; the renin–angiotensin II (Ang II)–aldosterone pathway; endothelin and its receptor A signaling in vascular smooth muscle; and impaired signaling pathways that produce vasodilation. However, which specific factor(s) are involved in the initiation of hypertension and also in the secondary response that is responsible for long-term blood pressure elevation remains largely undefined [4]. Recent intensive research in genetics offers opportunities to discover gene–environment interactions that may contribute to EH [5, 6, 7, 8]; however, so far, success has been limited mainly to identification of rare monogenic forms of hypertension. The vast majority of the genetic contribution to EH remains unexplained [9•]. Therefore, the exact etiology and pathogenesis of EH are still largely unknown. Currently, the treatment of EH is based on four major classes of antihypertensive medicine: blockers of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system, beta-adrenoreceptor antagonists, calcium channel blockers, and diuretics. Daily administration is essential, and none provides a long-term effective therapy for specific EH patients. Therefore, it has proved difficult for physicians to generate precise profiles for individual patients for the purposes of identifying specific therapies and predicting prognosis. Advanced research is urgently needed to understand the etiology and pathogenesis of EH and discover a new class of drug to fight against this common complex chronic disease. In the past 8 years, investigations on the role of CD4+ T lymphocytes (T cells) in hypertensive rat and mouse models have shown promise to make a breakthrough in understanding the pathogenesis of hypertension. The findings combined with a limited data from human hypertension research provide an important clue to gain insights in the pathogenesis of EH and will promote to identify novel targets for the effective prevention and treatment of EH.

Role of T Cells in the Pathogenesis of Hypertension

Five decades ago, several investigators raised the concept that activation of T cells might participate in the development of hypertension. Grollman et al. [10, 11] found that immunosuppression targeted toward adaptive immunity blunted hypertension and that transfer of lymphocytes from hypertensive rats induced by renal infarction led to the development of hypertension in control animals. Several studies showed that lymphocyte depletion by thymectomy or anti-lymphocyte serum prevented or blunted the development of hypertension in deoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA)-salt hypertension [12], Lyon hypertensive rats [13], hypertensive NZB mice [14], mice with partial renal infarction [15], and spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) [16]. In contrast, Ba et al. [17] found that depression of T cell function led to hypertension in SHR. They transplanted the thymus grafts or extracts from Wistar-Kyoto (WKY) rats to SHR, which led to a decrease in blood pressure in SHR. This was supported by administration of interleukin-2, a T cell growth factor, which prevented the development of hypertension in the young SHR and lowered blood pressure in hypertensive adult SHR [18]. Although these data clearly documented that the dysfunction of T cells is involved in the development of hypertension, further investigations on this subject have been limited in the last decade due to conflicting results on the effect of T cells in the development of hypertension.

With advances in immunology and genetic technology in recent years, the role of T cells in the pathogenesis of hypertension has re-attracted attention and interest of the researchers. In the early 2000s, Rodruiguez-Iturbe et al. found that immunosuppression with mycophenolate mofetil, which mainly targets B lymphocytes (B cells) and T cells, attenuated hypertension in SHR [19] and salt-induced hypertension after Ang II infusion [20]. The pioneering study from Dr. David Harrison’s group showed convincing evidence that functioning T cells participate in the development of Ang II and DOCA-salt-induced mouse hypertension. They found that the mice lacking recombinase-activating gene-1 (Rag-1), which cannot generate functional T cell receptors or B cell antibodies and thus lack both T and B cells, were resistant to the development of hypertension in response to either chronic Ang II infusion or DOCA-salt challenge. Adoptive transfer of effector Tcells, but not B cells, restored hypertensive response to these various stimuli [21]. In wild-type mice, Ang II increased circulating markers of effector memory T cells (e.g., CD69+, CCR5+, and CD44hi). In addition, unlike atherosclerosis, T cells (mostly CD4+ cells, fewer CD8+ cells) were accumulated in the perivascular adipose tissue (PVAT) of the aorta rather than around the endothelial layer [21]. Subsequent studies from this group displayed that Rag-1-null mice did not develop stress-induced hypertension, and the hypertensive response to the stimulus was restored by adoptive transfer of effector T cells from control mice [22]. These findings were supported by data from Crowley et al., who detected the hypertensive response to Ang II in mice that have severe combined immunodeficiency. These mice have a genetic abnormality leading to lack of T cells or B cells, in a scenario similar to Rag-1 knockout mice. These mice blunted Ang II-induced hypertension and increased sodium excretion and urine volumes compared with control mice [23].

Further support for the role of T cells in hypertension came from Mattson et al. who showed that deletion of the Rag-1 gene in Dahl salt-sensitive rats using zinc finger nuclease technology attenuated salt-induced hypertension [24]. Moreover, transfer of CD4+ cells from rats with preeclampsia to normal pregnant rats elevated blood pressure in the recipient rats [25]. All these data provide strong evidence to support the concept that activation of T cells contributes to the development of different forms of hypertension in mice and rats.

To determine whether Tcell activation in this process needs to activate antigen presentation cells and costimulation, Vinh et al. [26] exhibited evidence that costimulation is essential for T cell activation-induced hypertension. They showed that Ang II increased dendritic cell activation. Blockage of T cell costimulation using CTLA4-Ig, a CD28 interaction with B7 ligand inhibitor, or genetic deletion of molecules involved in the B7/CD28 costimulation axis prevented T cell activation, T cell cytokine production, and vascular Tcell accumulation and decreased Ang II and DOCA-salt-induced hypertension [26].

It is well known that the central nervous system (CNS) contributes to the development of hypertension. To document whether the CNS mediates hypertensive stimuli-induced T cell activation, Dr. Harrison’s group has carried out a series of investigations. They found that tissue-specific deletion of extracellular superoxide dismutase in the circumventricular organs increased reactive oxygen species levels, enhanced sympathetic nervous activity, and slightly elevated basal blood pressure [27]. Infusion of Ang II at a sub-pressor response dose into these knockout mice led to a significantly elevated blood pressure and T cell accumulation in the aorta [27]. These results were confirmed by their following study, which generated an electrolytic lesion in the anteroventral third cerebral ventricle (AV3V). Mice with the lesion blunted Ang II-induced T cell activation and aortic infiltration and blood pressure elevation [28], suggesting that Ang II-induced T cell activation is mediated by the central sympathetic system rather than having a direct effect on T cells to participate in the development of hypertension. Mice with AV3V lesions infused with norepinephrine become hypertensive and exhibited T cell activation and aortic infiltration [28]. This supports the concept that sympathetic drive and its attendant release of norepinephrine likely mediates T cell activation and hypertension. These results place an emphasis on the crucial role of the CNS in mediating the T cell activation that leads to hypertension. Prior studies by Ganta et al. [29] demonstrating enhanced sympathetic nerve activity to the spleen and increased expression of multiple cytokines in the spleen by intracerebro-ventricular infusion of Ang II support this conclusion. Recently, Zhang et al. [30] showed that selective deletion of Ang II receptor in mouse T cells using Cre-lox technology failed to prevent the development of hypertension induced by Ang II. These results rule out the direct role of Ang II in T cell activation-induced hypertension and indirectly support the concept that Ang II activates T cells through the CNS. In addition to the important role of the CNS, peripheral mechanisms may also contribute to T cell activation and vascular inflammation. Administration with hydralazine to normalize blood pressure and prevent T cell activation and vascular inflammation induced by Ang II infusion suggests that T cells may respond to high blood pressure [28].

Role of Specific T Cell Subsets and Their Cytokines in Hypertension

While T cells have clearly been shown to contribute to the development of hypertension as discussed above, these studies did not examine the role of specific subsets of T cells and their cytokines in hypertension. During development in lymphoid tissues, CD3+ T lymphocytes mature into either CD4+ or CD8+ single-positive cells and leave the thymus and become immunocompetent. In response to combined stimulation with antigens, costimulators, and particular cytokines, naïve CD4+ T helper (Th) cells can be differentiated into Th1, Th2, and Th17 effector cells or T regulatory lymphocytes (Tregs). Th1-polarized cells secrete signature cytokines, including interferon gamma (IFN-γ), interleukin (IL)-2, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and TNFβ. Th2 cells generate IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β). Th17 cells produce IL-17, and Tregs secrete IL-10. CD8+ T cells differentiate into cytotoxic (Tc) cells that produce perforin, granzyme B, IFN-γ, and TNF-α [31, 32].

T Effector Cells and Their Cytokines in Hypertension

It has been shown that Ang II infusion into rats led to an increase in pro-inflammatory Th1 phenotype, as indicated by increased Th1 cytokine IFN-γ production [33, 34] and a decrease in Th2-mediated responses, including IL-4 production. These effects can be blocked by an Ang II receptor 1a antagonist [34]. Although increased IFN-γ seems not to be required for blood pressure elevation [35], an expanded Th1 cell number would increase TNF-α production. Administration of a TNF-α antagonist, etanercept, prevented Ang II-induced hypertension and fructose-fed-mediated hypertension [21, 36]. In addition, there are several chemokine receptors characteristically found on the surface of Th1 cells, one of which is C-X-C chemokine receptor type 6, which interacts with the chemokine ligand 16. Chemokine ligand 16 deficiency has been shown to suppress infiltration of macrophages and CD3+ T cells in the kidneys of Ang II-treated mice [37]. Therefore, polarized Th1-mediated responses may contribute to the pathogenesis of hypertension.

Th17 cells are a new subset of CD4+ cells and produce cytokine IL-17, contributing to autoimmune disease and cardiovascular disease [38, 39]. Though they originally were thought to develop independently of the Th1 or Th2 lineages, recent research has shown flexibility in their late developmental programming, demonstrating overlap with Th1 cells [40]. Increased local IL-6 levels with TGF-β promote CD4+ naïve T cell differentiation into Th17 cells [39], and IL-17 has been demonstrated to contribute to a vascular inflammatory response and is an important mediator of Ang II-induced hypertension. Madhur et al. [41] showed that Ang II-induced hypertension is closely related to increased Th17 cells and IL-17 production. In their study, IL17-null mice receiving chronic infusion of Ang II displayed a similar increase in blood pressure to wild-type mice in the first 7 days (both basal ~120 vs. ~162 mmHg), but after 1 week of treatment, elevated blood pressure was markedly reduced in IL17-deleted mice compared with control at the end of 4-week Ang II infusion (~150 vs. ~170 mmHg) [41]. The vessels from IL17-null mice exhibited preserved vascular function, reduced superoxide production, and decreased aortic T cell infiltration by 4-week Ang II infusion [41]. Thus, IL-17 seems to be a critical cytokine that participates in maintenance of hypertension. In addition, IL-17 has been shown to induce chemokines and adhesion molecules in tissues that may promote tissue accumulation of other inflammatory cells (e.g., macrophages) [41]. In another study, IL-17 infusion to C57BL/6 mice significantly increased systolic blood pressure and decreased NO-mediated vessel relaxation [42]. Th17 cell activation was also associated with DOCA-salt-induced hypertension in rats. Treatment of these DOCA-salt hypertensive rats with an anti-IL-17 antibody reduced hypertension [43•]. Moreover, high-salt diet can induce Th17 cell development through the p38/MAPK pathway in mice [44]. Taken together, these data suggest that Th17 cells, by releasing IL-17, play an important role in T cell activation-mediated hypertension.

T Regulatory Cells and Their Cytokines in Hypertension

CD4+ naïve T cells can also differentiate into a small proportion of Tregs, including natural and inducible Tregs [45]. Natural Tregs develop in the thymus and constitute the majority of circulating Tregs, and inducible Tregs differentiate from conventional CD4+ T cells in peripheral tissues in response to antigens and cytokines. Increased local IL-6 levels in concert with TGF-β suppress CD4+ naïve T cell differentiation into Tregs [46]. Tregs express transcription factor forkhead box P3 (Foxp3) and surface marker CD25. Mice with genetic deletion of FoxP3 led to a loss of Tregs and displayed a severe, fatal lymphoproliferative disorder. Tregs are able to inhibit innate and adaptive immune responses to various stimuli, including autoantigens and infectious agents; thus, they play an important role in the maintenance of normal peripheral immune homeostasis and self-tolerance to protect from autoimmune diseases [47].

The identification of Tregs as a novel regulator of hypertension initially came from studies by Dr. Schiffrin’s group [48]. They used consomic rats harboring the Dahl salt-sensitive genome with a substitution of chromosome 2 of the Brown Norway normotensive strain. Chromosome 2 contains quantitative trait loci for hypertension and pro-inflammatory genes. The authors showed that consomic rats had reduced blood pressure, reduced vascular hypertrophy, reduced aortic T effector cell infiltration, and increased aortic Tregs, as evidenced by elevated Foxp3 expression and increased activity of CD4+CD25+ and CD8+CD25+ lymphocytes compared to Dahl salt-sensitive rats. The genetic substitution in the consomic rats resulted in increased local production of anti-inflammatory cytokines, IL-10, and TGF-β, induced by Tregs compared with that of the Dahl salt-sensitive rats. These findings indicate that Tregs could mitigate vascular inflammation and blood pressure elevation in the consomic animals [48]. Further studies from the same group support the concept that Tregs modulate hypertension and end-organ damage. Barhoumi et al. [49•] showed that Ang II infusion increased systolic blood pressure by 43 mmHg and caused a 43 % reduction in Foxp3+ cells in mouse renal cortex. Adoptive transfer of Tregs in C57BL/6 mice reduced Ang II-induced high blood pressure by ~10–15 mmHg using a telemetric measurement, which was accompanied by decreased vascular oxidative stress, macrophage, and T cell infiltration in the aortic adventitia and PVAT, and reduced plasma IFN-γ, IL-6, and TNF-α levels. In another study, Kasal et al. [50] demonstrated that adoptive transfer of Tregs prevented aldosterone-induced vascular injury and tended to decrease aldosterone-induced hypertension. Studies from other groups showed similar results. Kvakan et al. [51] showed that adoptive transfer of Tregs ameliorated Ang II-induced cardiac damage, but failed to show reduction in Ang II-induced hypertension. In contrast, Matrougui et al. [52] reported that intraperitoneal injection of Tregs three times a week for 2 weeks reduced Ang II-induced mean arterial blood pressure by ~12–15 mmHg. The Treg injection completely reversed Ang-II-decreased Treg cell numbers and IL-10 levels. The infusion also markedly reduced Ang II-induced vascular macrophage infiltration and TNF-α expression, and ameliorated coronary arteriolar endothelial dysfunction. The discrepancies in the effect of adoptively transferred Tregs on pressor agonist-stimulated blood pressure elevation in different groups could be due to variations in the amount and frequency of the Treg transfer and a limited role in reduction of blood pressure caused by Tregs alone.

Tregs are thought to exert their anti-inflammatory function through production of IL-10, although other mechanisms are also involved [53, 47]. IL-10 possesses a potent anti-inflammatory property, including suppression of IL-6 and TNF-α, and a cardiovascular protective role in hypertension. Didion et al. [54] showed that carotid arteries from IL-10-null mice exposed to Ang II produced significant endothelial dysfunction and increased vascular superoxide, while arteries of wild-type mice showed a minor effect. Kassan et al. [55] transferred cultured Tregs isolated from control mice into hypertensive IL-10-null mice, which reduced systolic blood pressure and NADPH oxidase activity and improved endothelium-dependent mesenteric artery relaxation. Treatment with IL-10 in Ang II-induced hypertensive mice had a similar effect. In contrast, transfer of Tregs from IL-10 knockout mice into Ang II-induced hypertensive mice failed to reduce blood pressure and ameliorated endothelial dysfunction. Chatterjee et al. [56] provided further evidence that IL-10 contributes to the development of hypertension. They showed that pregnant IL-10 knockout mice exhibited a significant increase in systolic blood pressure, endothelial dysfunction, and serum pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α and IFN-γ. Furthermore, toll-like receptor 3 activation during pregnancy exacerbated preeclampsia-like symptoms in IL-10-deficient mice [56].

All these studies suggest that Tregs have potent antihypertensive properties, at least partly through released IL-10 production.

Molecular Mechanism Underlying Dysregulation of T Cell Subsets Contributing to Hypertension

Neoantigen Two-Hit Hypothesis

The neoantigen two-hit hypothesis was raised by Dr. Harrison’s group [57, 58, 59] and updated recently [60•]. This is based on convincing evidence from their research showing that T cell activation is essential for the development of Ang II and salt-induced hypertension, and hypertensive stimuli-induced Tcell activation is mediated by increased sympathetic outflow. Treatment with the vasodilator hydralazine to prevent hypertension and reduce T cell activation and vascular T cell infiltration induced by Ang II infusion was considered evidence that modest hypertension occurs first in this model, and this results in T cell activation and perivascular infiltration, which drive the progression to severe hypertension. Therefore, they hypothesized that initial vascular damage caused by modest hypertension leads to producing neoantigens, possibly generated by oxidative stress, which activate T cells through stimulation of dendritic cells and upregulation of costimulatory molecular expression.

This hypothetic paradigm might turn out to be true. However, it is difficult to find the neoantigens that specifically respond to the pathogenic T cells in hypertension. A similar hypothesis has been proposed for the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, but decades of intense studies have failed to identify the relevant antigens recognized by pro-atherogenic T cells, despite the presence of several candidates. In addition, hydralazine may first block Ang II-sympathetic outflow-norepinephrine axis-stimulated mediators (e.g., IL-6), which inhibit T cell activation and lead to reduction of blood pressure.

Locally Increased IL6-Th17/Tregs Imbalance Hypothesis

Human IL-6 is a secreted glycoprotein containing 184 amino acids with a four-helix-bundle structure. IL-6 expresses in many different cells, including hepatocytes, macrophages, T cells, perivascular adipocytes, fibroblasts, and vascular smooth muscle cells. It has extensive functions in different tissues. Increased IL-6 signaling strongly induces the expression of acute-phase proteins, such as C-reaction protein and serum amyloid A in the liver. CD4+ T cells differentiate into Th17 cells or Tregs, depending on the local cytokine milieu. Differentiation toward Th17 and Tregs is mutually exclusive. Combined with TGF-β, increased IL-6 has been clearly shown to be essential to drive T17 cell differentiation and inhibit the development of Tregs from CD4+ T cells, leading to imbalance of Th17 cells/Tregs [61]. IL-6 also promotes CD8+ T cells to induce cytotoxic T cells [32].

Serum IL-6 levels significantly increased in many hypertensive animal models [62, 63]. Luther et al. [64] showed that Ang II induced IL-6 expression through a mineralocorticoid receptor mechanism. Four different research groups [62, 65, 66, 67] have clearly shown that IL-knockout mice markedly blunted Ang II-induced hypertension. IL-6 is also essential for stress-induced hypertension [68]. All these data confirm that IL-6 contributes to the development of hypertension. Interestingly, recent studies have indicated that dysfunction of Th17/Tregs differentiation also participates in the pathogenesis of hypertension. Amador et al. [43•] found Th17 cell activation and downregulation of Tregs in the peripheral tissue, heart, and kidney in DOCA-salt-induced hypertensive rats. Administration of spironolactone, which has been shown to effectively reduce salt-induced high blood pressure, prevented Th17 cell activation and increased Treg number in these DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. Treatment with an anti-IL-17 antibody reduced arterial hypertension and pro-inflammatory cytokines in these rats. Barhoumi et al. [49•] showed that Ang II induced hypertension and reduced Tregs by 43 % in the renal cortex. Adoptive transfer of Tregs reduced Ang II-induced hypertension. Madhur et al. [41] found that Ang II-induced hypertension was related to increased Th17 cells and IL-17 production. Genetic deletion of IL-17 blunted Ang-II-induced blood pressure elevation. Chiasson et al. [69] showed that treating mice with tacrolimus (FK506) for 1 week decreased splenic Tregs and increased Th17 cells and developed hypertension. The treatment also resulted in markedly increased serum levels of IL-6, IL-17a, and IL-23. In addition, preeclampsia rats have been shown to display lower levels of Tregs and higher Th17 cells and IL-6 levels [70]. Adoptive transfer of CD4+ T cells from preeclampsia rats into normal pregnant rats induced a significant increase in blood pressure [25]. Taken together, these studies suggest that, through both directly and indirectly, hypertensive stimuli increase local IL-6 levels in the cardiovascular system and kidney, which may promote peripheral imbalance of Th17 and Treg differentiation. Increased IL-17 and decreased Tregs and IL-10 in PVAT and adventitia contribute to the development of hypertension in different animal models.

The next question is how hypertensive stimuli initially increase local IL-6 expression. Harrison’s group clearly showed that Ang II stimulates T cell activation and infiltration in PVAT and hypertension, mainly through enhanced central sympathetic activity. Norepinephrine, a sympathetic terminal release substance, also promotes T cell activation and infiltration and the development of hypertension [28]. Norepinephrine stimulates IL-6 expression in other cells [71, 72]. Therefore, it is possible that Ang II mediates T cell activation and infiltration through central sympathetic released norepinephrine, which stimulates IL-6 expression, leading to dysfunction of Th17 cell/Treg differentiation and contributing to the pathogenesis as mentioned above. Recently, Harwani et al. [73•] provided some evidence in support of this concept. They showed that nicotine and Ang II enhanced the toll-like receptor (TLR)-mediated IL-6 release in prehypertensive SHR splenocytes, while nicotine inhibited the TLR-mediated IL-6 response in those of WKY rats. They confirmed that nicotine enhanced TLR-mediated IL-6 release in SHR and suppressed the effect in WKY rats in vivo. Like splenocytes, PVAT is also rich in autonomic nervous distribution, and it is reasonable to speculate that dysfunction of autonomic nervous system-mediated enhanced IL-6 expression in PVAT prior to the development of genetic hypertension in SHR.

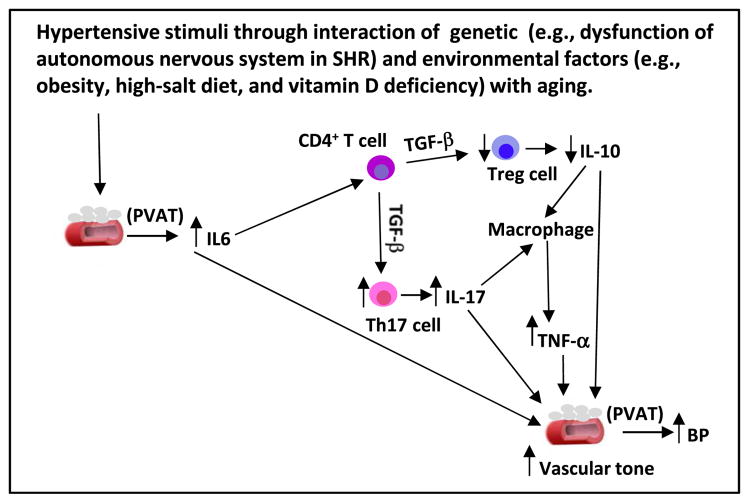

Based on these published data, it is highly possible that increased IL-6 expression in PVAT by hypertensive stimuli, such as Ang II, stress by increased sympathetic outflow, autonomic nervous dysfunction in genetic hypertension, and environmental factors (e.g., obesity and vitamin D deficiency) with aging lead to an imbalance in Th17 cell/Treg differentiation and increased IL-17 and decreased IL-10 levels, which attract other activated immune cells, such as macrophages, producing TNF-α. Sustained increase in IL-6, IL-17, and TNF-α and a decrease in Tregs and IL-10 in PVAT lead to elevation in vascular tone, which triggers the development of hypertension. This hypothesis is depicted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

A schematic diagram shows that hypertensive stimuli through interaction of genetic (e.g., dysfunction of autonomous nervous system in SHR) and environmental factors (e.g., obesity, high-salt diet, and vitamin D deficiency) with aging increase IL-6 level in adventitia and perivascular adipose tissue (PVAT) from adipocytes, fibroblasts, and vascular smooth muscle cells. A locally higher level of IL-6 functions as a chemokine of CD4+ T cells to stimulate their differentiation to Th17 cells producing high levels of IL-17, and inhibits them from generating Treg cells, leading to lower IL-10 levels. Increased IL-17/IL-10 ratio in adventitia and PVAT will attract and activate macrophages to produce TNF-α. A sustainable increase in IL-6, IL-17, and TNF-α and a decrease in Treg cells and IL-10 in perivascular settings will trigger an elevation in vascular tone and BP

It is noted here that increased IL-6 may not contribute to all forms of hypertension. Sturgis et al. [63] reported that DOCA salt stimulated IL-6 expression and induced hypertension in wild-type mice, but there was no difference in DOCA salt-induced hypertension between IL-6 knockout and wild-type mice, despite only a limited number of animals used in each group. While further studies will be needed to confirm these results, alternatively, DOCA salt-induced IL-1β and TNF-α release [43•, 74], both of which can induce Th17 cell differentiation [75, 76], may contribute to an imbalance of Th17 cell/Tregs in DOCA salt-induced hypertension.

Clinical Evidence for Dysfunction of T Cell Subsets in Human Hypertension

Recent research has displayed that serum levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-6, are positively associated with EH [77]. While Th17 cells were markedly decreased in healthy compared to preeclamptic pregnancies, Tregs was significantly higher in normal compared to preeclamptic pregnancies [78]. These results indicate that preeclampsia in the absence of a normal system moving away from IL-17 production toward Treg generation, leading to imbalance of Th17/Tregs, may play a critical role in preeclampsia-induced hypertension. In a small study, eight patients with stage 1 EH and normal renal function received an immunosuppressor, mycophenolate mofetil, for their psoriasis or rheumatoid arthritis. The treatment significantly reduced their blood pressure over 3 months, suggesting that immune suppression effectively lowers human elevated blood pressure [79]. A cohort study examined the effect of HIV infection and highly active antiretroviral therapy on hypertension in 5578 participants. Seaberg et al. [80] found that, controlling for age, race, body mass index, and smoking, HIV-positive men not taking antiretroviral therapy with lower CD4+ T cells had significantly lower systolic blood pressure than HIV-negative men. The patients receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy for more than 2 years (increased CD4+ T cells) had a markedly increased risk of developing hypertension. These results indicated that CD4+ T cells participate in the development of human hypertension. Recently, Youn et al. [81•] showed increased C-X-C chemokine receptor type 3, a tissue-homing chemokine serving as a T cell attractant, and cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, which secrete TNF-α, IFN,-γ, and granzyme B, in human hypertensive patients. Unfortunately, the studies did not measure serum or local IL-6 levels to determine whether IL-6 induces cytotoxic CD8+ T cells. Whether increased cytotoxic CD8+ T cells contribute to the development of human hypertension or result from hypertension remains unclear. Overall, these preliminary human data suggest that T cells, especially subsets of CD4+ T cells, may participate in human hypertension.

Conclusion

A growing body of evidence supports the critical role of T cells in experimental and human hypertension. One key advance is the finding that imbalance of distinct functions of T cell subsets could be an initiating event in the pathogenesis of hypertension, based on the studies predominantly in rat and mouse models. While hypertension-specific neoantigens may be identified in future studies as key factors mediating T cell activation, locally increased IL-6 levels by different hypertensive stimuli may act as an initiating factor to trigger an imbalance of Th17 cell/Tregs in PVAT that play a critical role in the pathogenesis of hypertension. These newly acquired insights mainly found in animal models may implicate in human application for EH that will lead to novel approaches in the prevention and treatment of EH.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by LB692 Clinical and Translational Research Grant (to S Chen) and NIH R01 HL120659 (to DK Agrawal). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Conflict of Interest Songcang Chen and Devendra K. Agrawal declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Pathogenesis of Hypertension

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

- 1.Chen S. Essential hypertension: perspectives and future directions. J Hypertens. 2012;30(1):42–5. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32834ee23c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawes CM, Vander Hoorn S, Rodgers A International Society of H. Global burden of blood-pressure-related disease, 2001. Lancet. 2008;371(9623):1513–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60655-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, Cushman WC, Dennison-Himmelfarb C, Handler J, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8) JAMA. 2014;311(5):507–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lifton RP, Gharavi AG, Geller DS. Molecular mechanisms of human hypertension. Cell. 2001;104(4):545–56. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00241-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.International Consortium for Blood Pressure Genome-Wide Association S. Ehret GB, Munroe PB, Rice KM, Bochud M, Johnson AD, et al. Genetic variants in novel pathways influence blood pressure and cardiovascular disease risk. Nature. 2011;478(7367):103–9. doi: 10.1038/nature10405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kato N, Takeuchi F, Tabara Y, Kelly TN, Go MJ, Sim X, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies identifies common variants associated with blood pressure variation in East Asians. Nat Genet. 2011;43(6):531–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levy D, Ehret GB, Rice K, Verwoert GC, Launer LJ, Dehghan A, et al. Genome-wide association study of blood pressure and hypertension. Nat Genet. 2009;41(6):677–87. doi: 10.1038/ng.384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Newton-Cheh C, Johnson T, Gateva V, Tobin MD, Bochud M, Coin L, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies eight loci associated with blood pressure. Nat Genet. 2009;41(6):666–76. doi: 10.1038/ng.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9•.Coffman TM. Under pressure: the search for the essential mechanisms of hypertension. Nat Med. 2011;17(11):1402–9. doi: 10.1038/nm.2541. The article provides a comprehensive overview regarding the advanced progress of hypertension research in recent years. Especially, it places great emphasis on mechanistic understanding of hypertension. The author proposed future studies in assessing the therapeutic value of manipulating these newly identified pathways will be helpful for developing more effective approaches to management of the patients with hypertension. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okuda T, Grollman A. Passive transfer of autoimmune induced hypertension in the rat by lymph node cells. Tex Rep Biol Med. 1967;25(2):257–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.White FN, Grollman A. Autoimmune factors associated with infarction of the kidney. Nephron. 1964;1:93–102. doi: 10.1159/000179322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Svendsen UG. Evidence for an initial, thymus independent and a chronic, thymus dependent phase of DOCA and salt hypertension in mice. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand A. 1976;84(6):523–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1976.tb00150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bataillard A, Freiche JC, Vincent M, Sassard J, Touraine JL. Antihypertensive effect of neonatal thymectomy in the genetically hypertensive LH rat. Thymus. 1986;8(6):321–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Svendsen UG. Spontaneous hypertension and hypertensive vascular disease in the NZB strain of mice. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand A. 1977a;85(4):548–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1977.tb03887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Svendsen UG. The importance of thymus in the pathogenesis of the chronic phase of hypertension in mice following partial infarction of the kidney. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand A. 1977b;85(4):539–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1977.tb03886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bendich A, Belisle EH, Strausser HR. Immune system modulation and its effect on the blood pressure of the spontaneously hypertensive male and female rat. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1981;99(2):600–7. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(81)91787-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ba D, Takeichi N, Kodama T, Kobayashi H. Restoration of T cell depression and suppression of blood pressure in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) by thymus grafts or thymus extracts. J Immunol. 1982;128(3):1211–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tuttle RS, Boppana DP. Antihypertensive effect of interleukin-2. Hypertension. 1990;15(1):89–94. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.15.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodriguez-Iturbe B, Quiroz Y, Nava M, Bonet L, Chavez M, Herrera-Acosta J, et al. Reduction of renal immune cell infiltration results in blood pressure control in genetically hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2002;282(2):F191–201. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.0197.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodriguez-Iturbe B, Pons H, Quiroz Y, Gordon K, Rincon J, Chavez M, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil prevents salt-sensitive hypertension resulting from angiotensin II exposure. Kidney Int. 2001;59(6):2222–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guzik TJ, Hoch NE, Brown KA, McCann LA, Rahman A, Dikalov S, et al. Role of the T cell in the genesis of angiotensin II induced hypertension and vascular dysfunction. J Exp Med. 2007;204(10):2449–60. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marvar PJ, Vinh A, Thabet S, Lob HE, Geem D, Ressler KJ, et al. T lymphocytes and vascular inflammation contribute to stress-dependent hypertension. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;71(9):774–82. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crowley SD, Song YS, Lin EE, Griffiths R, Kim HS, Ruiz P. Lymphocyte responses exacerbate angiotensin II-dependent hypertension. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;298(4):R1089–97. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00373.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mattson DL, Lund H, Guo C, Rudemiller N, Geurts AM, Jacob H. Genetic mutation of recombination activating gene 1 in Dahl salt-sensitive rats attenuates hypertension and renal damage. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2013;304(6):R407–14. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00304.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Novotny SR, Wallace K, Heath J, Moseley J, Dhillon P, Weimer A, et al. Activating autoantibodies to the angiotensin II type I receptor play an important role in mediating hypertension in response to adoptive transfer of CD4+ T lymphocytes from placental ischemic rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2012;302(10):R1197–201. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00623.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vinh A, Chen W, Blinder Y, Weiss D, Taylor WR, Goronzy JJ, et al. Inhibition and genetic ablation of the B7/CD28 T-cell costimulation axis prevents experimental hypertension. Circulation. 2010;122(24):2529–37. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.930446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lob HE, Vinh A, Li L, Blinder Y, Offermanns S, Harrison DG. Role of vascular extracellular superoxide dismutase in hypertension. Hypertension. 2011;58(2):232–9. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.172718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marvar PJ, Thabet SR, Guzik TJ, Lob HE, McCann LA, Weyand C, et al. Central and peripheral mechanisms of T-lymphocyte activation and vascular inflammation produced by angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Circ Res. 2010;107(2):263–70. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.217299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ganta CK, Lu N, Helwig BG, Blecha F, Ganta RR, Zheng L, et al. Central angiotensin II-enhanced splenic cytokine gene expression is mediated by the sympathetic nervous system. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289(4):H1683–91. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00125.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang JD, Patel MB, Song YS, Griffiths R, Burchette J, Ruiz P, et al. A novel role for type 1 angiotensin receptors on T lymphocytes to limit target organ damage in hypertension. Circ Res. 2012a;110(12):1604–17. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.261768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muller DN, Kvakan H, Luft FC. Immune-related effects in hypertension and target-organ damage. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2011;20(2):113–7. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3283436f88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tanaka T, Narazaki M, Kishimoto T. Therapeutic targeting of the interleukin-6 receptor. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2012;52:199–219. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010611-134715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mazzolai L, Duchosal MA, Korber M, Bouzourene K, Aubert JF, Hao H, et al. Endogenous angiotensin II induces atherosclerotic plaque vulnerability and elicits a Th1 response in ApoE−/− mice. Hypertension. 2004;44(3):277–82. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000140269.55873.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shao J, Nangaku M, Miyata T, Inagi R, Yamada K, Kurokawa K, et al. Imbalance of T-cell subsets in angiotensin II-infused hypertensive rats with kidney injury. Hypertension. 2003;42(1):31–8. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000075082.06183.4E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kossmann S, Schwenk M, Hausding M, Karbach SH, Schmidgen MI, Brandt M, et al. Angiotensin II-induced vascular dysfunction depends on interferon-gamma-driven immune cell recruitment and mutual activation of monocytes and NK-cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33(6):1313–9. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.301437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tran LT, MacLeod KM, McNeill JH. Chronic etanercept treatment prevents the development of hypertension in fructose-fed rats. Mol Cell Biochem. 2009;330(1–2):219–28. doi: 10.1007/s11010-009-0136-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xia Y, Entman ML, Wang Y. Critical role of CXCL16 in hypertensive kidney injury and fibrosis. Hypertension. 2013;62(6):1129–37. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eid RE, Rao DA, Zhou J, Lo SF, Ranjbaran H, Gallo A, et al. Interleukin-17 and interferon-gamma are produced concomitantly by human coronary artery-infiltrating T cells and act synergistically on vascular smooth muscle cells. Circulation. 2009;119(10):1424–32. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.827618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tesmer LA, Lundy SK, Sarkar S, Fox DA. Th17 cells in human disease. Immunol Rev. 2008;223:87–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00628.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Basu R, Hatton RD, Weaver CT. The Th17 family: flexibility follows function. Immunol Rev. 2013;252(1):89–103. doi: 10.1111/imr.12035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Madhur MS, Lob HE, McCann LA, Iwakura Y, Blinder Y, Guzik TJ, et al. Interleukin 17 promotes angiotensin II-induced hypertension and vascular dysfunction. Hypertension. 2010;55(2):500–7. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.145094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nguyen H, Chiasson VL, Chatterjee P, Kopriva SE, Young KJ, Mitchell BM. Interleukin-17 causes Rho-kinase-mediated endothelial dysfunction and hypertension. Cardiovasc Res. 2013;97(4):696–704. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43•.Amador CA, Barrientos V, Pena J, Herrada AA, Gonzalez M, Valdes S, et al. Spironolactone decreases DOCA-salt-induced organ damage by blocking the activation of T helper 17 and the downregulation of regulatory T lymphocytes. Hypertension. 2014;63(4):797–803. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.02883. This manuscript displays Th17-cell activation and downregulation of mRNA transcripts of forkhead box P3, a specific transcription factor of Tregs, in the peripheral tissue, heart, and kidney of DOCA-salt-induced hypertensive rats. Administration of spironolactone, which has been shown to effectively reduce salt-induced high blood pressure, prevented Th17-cell activation and increased Treg number in these DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. Treatment with an anti-IL-17 antibody reduced arterial hypertension and pro-inflammatory cytokines in these rats. The results suggest that alteration in Th17/Treg cells/IL-17 pathway induced by mineralocorticoid receptor activation contributes to mineralocorticoid-dependent hypertension. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kleinewietfeld M, Manzel A, Titze J, Kvakan H, Yosef N, Linker RA, et al. Sodium chloride drives autoimmune disease by the induction of pathogenic TH17 cells. Nature. 2013;496(7446):518–22. doi: 10.1038/nature11868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O’Shea JJ, Paul WE. Mechanisms underlying lineage commitment and plasticity of helper CD4+ T cells. Science. 2010;327(5969):1098–102. doi: 10.1126/science.1178334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kimura A, Kishimoto T. IL-6: regulator of Treg/Th17 balance. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40(7):1830–5. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vignali DA, Collison LW, Workman CJ. How regulatory T cells work. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(7):523–32. doi: 10.1038/nri2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Viel EC, Lemarie CA, Benkirane K, Paradis P, Schiffrin EL. Immune regulation and vascular inflammation in genetic hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298(3):H938–44. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00707.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49•.Barhoumi T, Kasal DA, Li MW, Shbat L, Laurant P, Neves MF, et al. T regulatory lymphocytes prevent angiotensin II-induced hypertension and vascular injury. Hypertension. 2011;57(3):469–76. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.162941. The study reports that Tregs are able to reduce Ang-II-induced vascular injury and partially prevent Ang II-mediated hypertension. The authors found that Ang II infusion increased systolic blood pressure by 43 mmHg and caused a 43 % reduction in Foxp3+ cells in mouse renal cortex. Adoptive transfer of Tregs in C57BL/6 mice reduced Ang II-induced high blood pressure by ~10–15 mmHg using a telemetric measurement, which was accompanied by decreased vascular oxidative stress, macrophage, and T cell infiltration in the aortic adventitia and PVAT, and reduced plasma levels of IFN-γ, IL-6, and TNF-α. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kasal DA, Barhoumi T, Li MW, Yamamoto N, Zdanovich E, Rehman A, et al. T regulatory lymphocytes prevent aldosterone-induced vascular injury. Hypertension. 2012;59(2):324–30. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.181123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kvakan H, Kleinewietfeld M, Qadri F, Park JK, Fischer R, Schwarz I, et al. Regulatory T cells ameliorate angiotensin II-induced cardiac damage. Circulation. 2009;119(22):2904–12. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.832782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Matrougui K, Abd Elmageed Z, Kassan M, Choi S, Nair D, Gonzalez-Villalobos RA, et al. Natural regulatory T cells control coronary arteriolar endothelial dysfunction in hypertensive mice. Am J Pathol. 2011;178(1):434–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kobie JJ, Shah PR, Yang L, Rebhahn JA, Fowell DJ, Mosmann TR. T regulatory and primed uncommitted CD4 T cells express CD73, which suppresses effector CD4 T cells by converting 5′-adenosine monophosphate to adenosine. J Immunol. 2006;177(10):6780–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.6780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Didion SP, Kinzenbaw DA, Schrader LI, Chu Y, Faraci FM. Endogenous interleukin-10 inhibits angiotensin II-induced vascular dysfunction. Hypertension. 2009;54(3):619–24. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.137158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kassan M, Galan M, Partyka M, Trebak M, Matrougui K. Interleukin-10 released by CD4(+)CD25(+) natural regulatory T cells improves microvascular endothelial function through inhibition of NADPH oxidase activity in hypertensive mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31(11):2534–42. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.233262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chatterjee P, Chiasson VL, Kopriva SE, Young KJ, Chatterjee V, Jones KA, et al. Interleukin 10 deficiency exacerbates toll-like receptor 3-induced preeclampsia-like symptoms in mice. Hypertension. 2011;58(3):489–96. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.172114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Harrison DG, Guzik TJ, Lob HE, Madhur MS, Marvar PJ, Thabet SR, et al. Inflammation, immunity, and hypertension. Hypertension. 2011;57(2):132–40. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.163576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Harrison DG, Vinh A, Lob H, Madhur MS. Role of the adaptive immune system in hypertension. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2010;10(2):203–7. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Marvar PJ, Lob H, Vinh A, Zarreen F, Harrison DG. The central nervous system and inflammation in hypertension. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2011;11(2):156–61. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60•.Harrison DG, Marvar PJ, Titze JM. Vascular inflammatory cells in hypertension. Front Physiol. 2012;3:128. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00128. This article comprehensively describes the effect of a variety of immune cells on vascular dysfunction, leading to hypertension in animal models. The authors also explored the mechanism of inflammatory cell-induced hypertension and proposed a neoantigen two-hit hypothesis linking the role of sympathetic nervous system, immune cells, and the production of cytokines in vascular and renal dysfunction, contributing to the development of hypertension. The article supports that studies of immune cell activation are very useful in understanding hypertension, a common yet complex disease. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.De Ciuceis C, Rossini C, La Boria E, Porteri E, Petroboni B, Gavazzi A, et al. Immune mechanisms in hypertension. High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s40292-014-0040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brands MW, Banes-Berceli AK, Inscho EW, Al-Azawi H, Allen AJ, Labazi H. Interleukin 6 knockout prevents angiotensin II hypertension: role of renal vasoconstriction and janus kinase 2/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 activation. Hypertension. 2010;56(5):879–84. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.158071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sturgis LC, Cannon JG, Schreihofer DA, Brands MW. The role of aldosterone in mediating the dependence of angiotensin hypertension on IL-6. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;297(6):R1742–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90995.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Luther JM, Gainer JV, Murphey LJ, Yu C, Vaughan DE, Morrow JD, et al. Angiotensin II induces interleukin-6 in humans through a mineralocorticoid receptor-dependent mechanism. Hypertension. 2006;48(6):1050–7. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000248135.97380.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Coles B, Fielding CA, Rose-John S, Scheller J, Jones SA, O’Donnell VB. Classic interleukin-6 receptor signaling and interleukin-6 trans-signaling differentially control angiotensin II-dependent hypertension, cardiac signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 activation, and vascular hypertrophy in vivo. Am J Pathol. 2007;171(1):315–25. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.061078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee DL, Sturgis LC, Labazi H, Osborne JB, Jr, Fleming C, Pollock JS, et al. Angiotensin II hypertension is attenuated in interleukin-6 knockout mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290(3):H935–40. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00708.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang W, Wang W, Yu H, Zhang Y, Dai Y, Ning C, et al. Interleukin 6 underlies angiotensin II-induced hypertension and chronic renal damage. Hypertension. 2012b;59(1):136–44. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.173328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lee DL, Leite R, Fleming C, Pollock JS, Webb RC, Brands MW. Hypertensive response to acute stress is attenuated in interleukin-6 knockout mice. Hypertension. 2004;44(3):259–63. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000139913.56461.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chiasson VL, Talreja D, Young KJ, Chatterjee P, Banes-Berceli AK, Mitchell BM. FK506 binding protein 12 deficiency in endothelial and hematopoietic cells decreases regulatory T cells and causes hypertension. Hypertension. 2011;57(6):1167–75. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.162917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lamarca B, Brewer J, Wallace K. IL-6-induced pathophysiology during pre-eclampsia: potential therapeutic role for magnesium sulfate? Int J Infereron Cytokine Mediat Res. 2011;2011(3):59–64. doi: 10.2147/IJICMR.S16320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Stohl LL, Zang JB, Ding W, Manni M, Zhou XK, Granstein RD. Norepinephrine and adenosine-5′-triphosphate synergize in inducing IL-6 production by human dermal microvascular endothelial cells. Cytokine. 2013;64(2):605–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yang R, Lin Q, Gao HB, Zhang P. Stress-related hormone norepinephrine induces interleukin-6 expression in GES-1 cells. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2014;47(2):101–9. doi: 10.1590/1414-431X20133346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73•.Harwani SC, Chapleau MW, Legge KL, Ballas ZK, Abboud FM. Neurohormonal modulation of the innate immune system is proinflammatory in the prehypertensive spontaneously hypertensive rat, a genetic model of essential hypertension. Circ Res. 2012;111(9):1190–7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.277475. The study reveals that nicotine and Ang II enhanced TLR-mediated IL-6 response in prehypertensive SHR splenocytes, while nicotine suppressed the TLR-mediated IL-6 response and Ang II had no effect in those of WKY rats. In vivo, nicotine enhanced plasma levels of TLR7/8-mediated IL-6 response in prehypertensive SHRs but suppressed this response in WKY rats. The finding provides important evidence that neurohormonal regulation of IL-6 expression plays a role in the pathogenesis of genetic hypertension. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bae EH, Kim IJ, Park JW, Ma SK, Lee JU, Kim SW. Renoprotective effect of rosuvastatin in DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25(4):1051–9. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lamacchia C, Palmer G, Seemayer CA, Talabot-Ayer D, Gabay C. Enhanced Th1 and Th17 responses and arthritis severity in mice with a deficiency of myeloid cell-specific interleukin-1 receptor antagonist. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(2):452–62. doi: 10.1002/art.27235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sugita S, Kawazoe Y, Imai A, Yamada Y, Horie S, Mochizuki M. Inhibition of Th17 differentiation by anti-TNF-alpha therapy in uveitis patients with Behcet’s disease. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14(3):R99. doi: 10.1186/ar3824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bautista LE, Vera LM, Arenas IA, Gamarra G. Independent association between inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, and TNF-alpha) and essential hypertension. J Hum Hypertens. 2005;19(2):149–54. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Santner-Nanan B, Peek MJ, Khanam R, Richarts L, Zhu E, Fazekas de St Groth B, et al. Systemic increase in the ratio between Foxp3+ and IL-17-producing CD4+ T cells in healthy pregnancy but not in preeclampsia. J Immunol. 2009;183(11):7023–30. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Herrera J, Ferrebuz A, MacGregor EG, Rodriguez-Iturbe B. Mycophenolate mofetil treatment improves hypertension in patients with psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(12 Suppl 3):S218–25. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006080918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Seaberg EC, Munoz A, Lu M, Detels R, Margolick JB, Riddler SA, et al. Association between highly active antiretroviral therapy and hypertension in a large cohort of men followed from 1984 to 2003. AIDS. 2005;19(9):953–60. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000171410.76607.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81•.Youn JC, Yu HT, Lim BJ, Koh MJ, Lee J, Chang DY, et al. Immunosenescent CD8+ T cells and C-X-C chemokine receptor type 3 chemokines are increased in human hypertension. Hypertension. 2013;62(1):126–33. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.00689. The pathogenic role of T cells in hypertension has largely been documented in experimental animals. It is not clear whether immune cells contribute to human hypertension. The study shows increased expression of C-X-C chemokine receptor type 3, a tissue-homing chemokine serving as a T cell attractant, and cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, which secrete TNF-α, IFN,-γ, and granzyme B, in human hypertensive patients. While the studies did not measure serum or local IL-6 levels to determine whether IL-6 induces cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, these preliminary human data suggest that T cells may participate in human hypertension. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]