Abstract

Phosphatidylinositol-3-kinases (PI3K) γ and δ are preferentially enriched in leukocytes, and defects in these signaling pathways have been shown to impair T cell activation. The effects of PI3Kγ and PI3Kδ on alloimmunity remain underexplored. Here, we show that both PI3Kγ −/− and PI3Kδ D910A/D910A mice receiving heart allografts have suppression of alloreactive T effector cells and delayed acute rejection. However, PI3Kδ mutation also dampens regulatory T cells (Treg). After treatment with low dose CTLA4-Ig, PI3Kγ −/−, but not PI3Κδ D910A/D910A, recipients exhibit indefinite prolongation of heart allograft survival. PI3Kδ D910A/D910A Tregs have increased apoptosis and impaired survival. Selective inhibition of PI3Kγ and PI3Kδ (using PI3Kδ and dual PI3Kγδ chemical inhibitors) shows that PI3Kγ inhibition compensates for the negative effect of PI3Kδ inhibition on long-term allograft survival. These data serve as a basis for future PI3K-based immune therapies for transplantation.

Phosphatidylinositol-3-kinases (PI3K) γ and δ are key regulators of T cell signaling. Here the author show, using mouse heart allograft transplantation models, that PI3Kγ or PI3Kδ deficiency prolongs graft survival, but selective inhibition of PI3Kγ or PI3Kδ reveals alternative transplant survival outcomes post CTLA4-Ig treatment.

Introduction

Current immunosuppressive drugs (ISD) commonly suppress both effector and regulatory axes of adaptive immunity and fail to induce immune regulation, which is critical for long-term graft acceptance. Furthermore, ISDs contribute to microvascular toxicity and organ failure, as well as major long-term complications such as malignancy, metabolic disorders, and infections1, 2. Therefore, the development of targeted immunomodulatory agents with improved efficacy and safety profiles3 in solid organ transplantation is highly desirable.

PI3Ks belong to the family of lipid kinases that phosphorylate the 3′OH-group of phosphatidylinositols to generate phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-triphosphate (PtdIns(3,4,5)p3), which then interacts with the pleckstrin-homology (PH)-domains of various signal transduction proteins including AKT4, 5. Class I PI3Ks are the best characterized of the different PI3K classes and are composed of regulatory subunits (p85) and catalytic subunits (p110α, p110β, p110δ, and p110γ). Class I PI3Ks are further classified as class IA or IB according to their modes of activation: class IA PI3Ks are activated downstream of tyrosine kinase receptors, whereas the class IB PI3K has only one subunit (PI3Kγ) and is activated by G protein-coupled receptors5, 6.

The γ and δ catalytic forms of PI3K are preferentially enriched in leukocytes and, through their capacity to regulate the function of immune cells5, 7–10, represent a promising drug target for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. Although PI3Kγ is activated by G protein-coupled receptors including the chemokine receptors, our data and others indicate that PI3Kγ-deficient T cells also have a diminished anti-CD3 proliferative response11–15. The importance of p110γ in alloimmune responses also lies in its capacity to regulate innate immune cells and inflammatory responses8. PI3Kδ is a sister isoform and lies downstream of tyrosine kinase-associated receptors, T cell receptor (TCR), co-stimulatory and cytokine receptors16–22. The lack of PI3Kδ is detrimental to effector T cells (Teff)23, 24.

Despite an accumulating body of data on the role of PI3Kγ and δ in immunity, the mechanisms by which the PI3Kγ and δ signaling pathways control alloimmune responses remains to be explored. Here, we show for the first time the role of PI3Kγ and PI3Kδ pathways in determining the fate of alloimmune responses.

Results

PI3Kγ or PI3Kδ deletion suppresses T cell alloreactivity

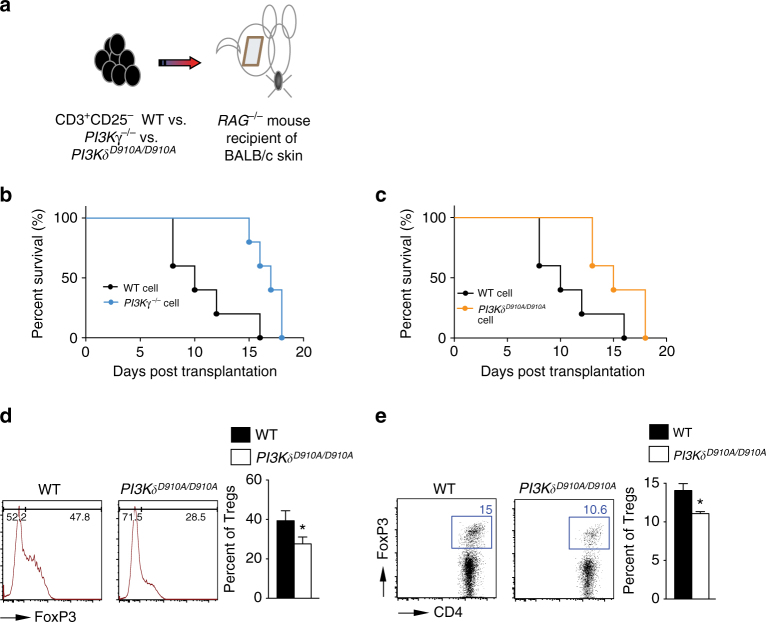

To study the effect of PI3Kγ and PI3Kδ deletion on alloimmune responses in vivo, we injected 6 × 106 CD3+CD25− T cells isolated from splenocytes of PI3Kδ D910A/D910A, PI3Kγ −/−, or WT naive mice, into RAG −/− recipients of BALB/c skin allograft at day 1 post-transplant (Fig. 1a). Graft survival in recipients of PI3Kγ −/− or PI3Kδ D910A/D910A T cells significantly exceeded that in recipients of control T cells (*p < 0.05, t-test, n = 5/group) (Fig. 1b, c). Interestingly, there was a significant decrease in regulatory T cell (Treg) induction in mice receiving PI3Kδ D910A/D910A compared to WT CD3+CD25− T cells (27.60% ± 4.07% vs. 39.35% ± 5.05%, respectively, p = 0.05, t-test, n = 3/group) (Fig. 1d). Similarly, under Treg polarizing conditions, there was a marked decrease in Treg induction in vitro in the PI3Kδ D910A/D910A group compared with WT (11.07% ± 0.26% vs. 14.07% ± 0.88%, respectively, *p < 0.05, t-test, n = 3–4/group) (Fig. 1e).

Fig. 1.

PI3Kγ or PI3Kδ deletion impairs T cell activation in vivo. a Schematics describing the methodology used in this experiment. RAG −/− mice received a BALB/c skin allograft; on day 1 post-transplant, the mice were injected with 6 × 106 CD3+CD25− T cells isolated from splenocytes of PI3Kγ −/−, PI3Kδ D910A/D910A or WT naive mice. b Graft survival in recipients of PI3Kγ −/− T cells significantly exceeded that in recipients of control T cells (MST of 17 vs. 10 days, respectively, *p < 0.05, t-test, n = 5/group). c Graft survival in recipients of PI3Kδ D910A/D910A T cells significantly exceeded that in recipients of control T cells (MST of 15 vs. 10 days, respectively, *p < 0.05, t-test, n = 5/group). d Representative figures of flow cytometry analysis of splenocytes retrieved from transplanted mice at day 7 post-transplant. Data shows significant decrease in Treg induction in the DLN of PI3Kδ D910A/D910A recipients of BALB/c skin and WT controls (*p < 0.05, t-test, n = 3/group). Bar graph represents the percentage of Tregs. e Representative example of FACS staining of CD4+ PI3Kδ D910A/D910A and WT T cells stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 Abs in the presence of IL-2 and TGFβ. (Data are representative of three separate experiments, *p < 0.05, t-test, n = 3–4/group). Bar graph represents the percentage of induced Tregs. d, e The graphs show data as mean ± s.e.m. (MST mean survival time; Treg regulatory T cell)

PI3Kγ or PI3Kδ deletion impairs T cell activation in vitro

PI3Kγ −/− splenocytes proliferated significantly less when stimulated with allogeneic cells, as measured by thymidine incorporation (Supplementary Fig. 1A). Similarly, alloantigen stimulation of PI3Kγ −/−-deficient T cells led to a significantly lower frequency of interferon (IFN)γ producing T cells than WT controls (Supplementary Fig. 1B). PI3Kδ D910A/D910A CD4+ and CD8+ T cells also proliferated significantly less than WT T cells upon stimulation with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies, as measured by thymidine incorporation (Supplementary Fig. 1C, D).

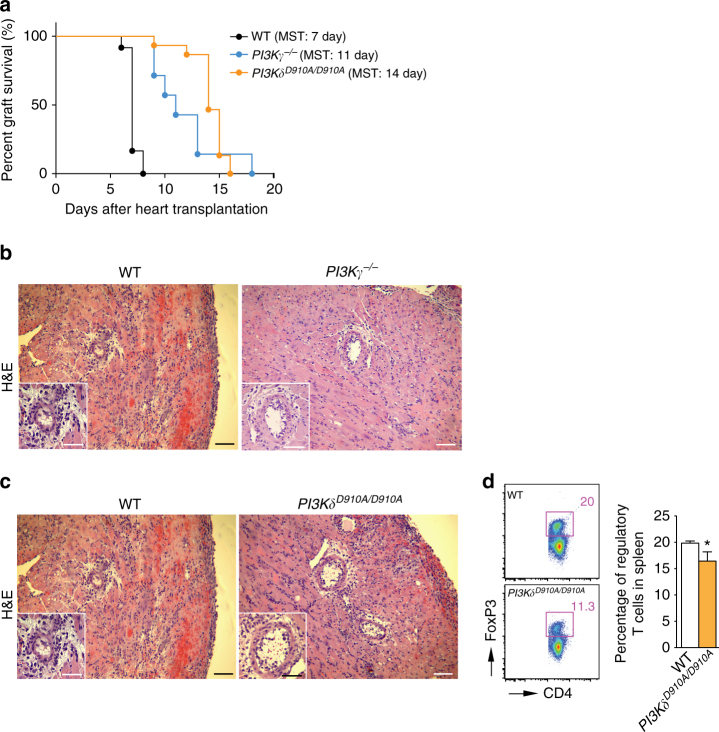

PI3Kγ or PI3Kδ deletion prolongs heart allograft survival

We first used a model of acute cardiac transplant rejection as a preclinical model to study the immunosuppressive role of PI3Kγ and PI3Kδ deletion. Naive BALB/c heart allografts were transplanted into fully allogeneic C57BL/6 (WT) recipients, PI3Kγ −/− C57BL/6 (PI3Kγ −/−) recipients or PI3Kδ D910A/D910A C57BL/6 (PI3Kδ D910A/D910A) recipients. PI3Kγ −/− and PI3Kδ D910A/D910A recipients exhibited prolonged allograft survival compared to WT recipients (mean survival time, (MST) PI3Kγ −/− vs. WT: MST of 11 vs. 7 days, respectively, *p < 0.05, t-test, n = 10/group, PI3Kδ D910A/D910A vs. WT: MST of 14 vs. 7 days, respectively, *p < 0.05, t-test, n = 10–14/group) (Fig. 2a). Accordingly, PI3Kγ −/− and PI3Kδ D910A/D910A recipients showed marked reduction in the severity of acute rejection of the heart allograft as assessed by histological analysis (Fig. 2b, c). We also observed a significant decrease in the number of CD4+ and CD8+ effector cells (CD44HighCD62LLow) in the secondary lymphoid tissues of PI3Kγ −/− recipients compared to WT (at day 7 post-transplant) (*p < 0.05, t-test, n = 6/group) (Supplementary Fig. 2A–D). Furthermore, PI3Kγ −/− recipients showed reduced T cell proliferative responses and suppression of inflammatory cytokine production at 7 days post-transplantation as assessed by MLR and luminex-assays (*p < 0.05, t-test, n = 4–6/group) (Supplementary Fig. 2E–G).

Fig. 2.

PI3Kγ or PI3Kδ inhibition suppresses acute rejection. Naive BALB/c heart allografts were transplanted into fully allogeneic C57BL/6 (WT), PI3Kγ −/−, or PI3Kδ D910A/D910A recipients. a PI3Kγ −/− recipients exhibited prolonged allograft survival compared to WT recipients (MST of 11 vs. 7 days respectively, *p < 0.05, t-test, n = 10/group). PI3Kδ D910A/D910A recipients of BALB/c hearts showed significant prolongation of heart allograft survival compared to control (MST of 14 vs. 7 days, respectively, *p < 0.05, t-test, n = 10–14/group). b Representative examples of H&E staining of cardiac allograft histology show well-preserved myocytes and lower cellular inflammatory infiltrate at 7 days post-transplant in the PI3Kγ –/– mice compared to WT controls (Scale bar 50 μm, inset scale bar 25 μm). c Representative examples of cardiac allograft histology show well preserved myocytes and lower cellular inflammatory infiltrate at 7 days post-transplant in the PI3Kδ D910A/D910A mice compared to WT controls (H&E stain, scale bar 50 μm, inset scale bar 25 μm). d Representative dot plots of Tregs (CD4+FoxP3+) in splenocytes of WT and PI3Kδ D910A/D910A recipients at day 7 post-transplant. Bar graph represents the percentage of Tregs in splenocytes in PI3Kγ −/− recipients compared to WT at day 7 post-transplant (*p < 0.05, t-test, n = 6/group, the graph shows data as mean ± s.e.m.). (MST mean survival time, Treg regulatory T cell)

Similarly, flow cytometric analysis of secondary lymphoid tissue of PI3Kδ D910A/D910A recipients showed fewer CD4+ and CD8+ effector T cells as compared to WT recipients (*p < 0.05, t-test, n = 6/group) (Supplementary Fig. 3A, B, D, and E). However, there was significant decrease in the percentage of Tregs in secondary lymphoid tissue of PI3Kδ D910A/D910A recipients of BALB/c allografts compared to WT recipients at day 7 post-transplant (*p < 0.05, t-test, n = 6/group) (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 3C).

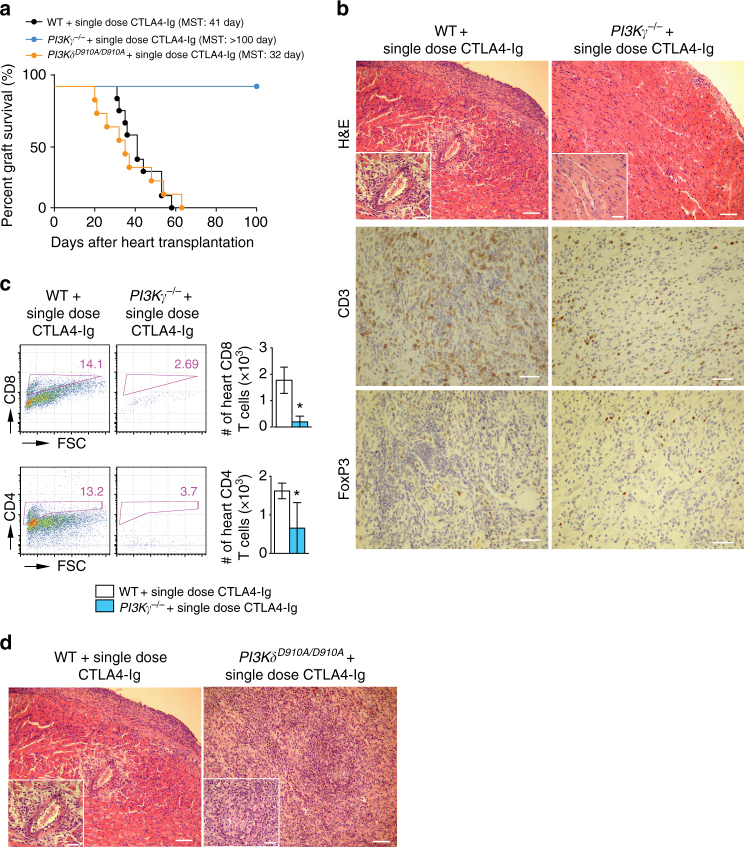

PI3Kγ or PI3Kδ deletion and long-term allograft survival

While single dose CTLA4-Ig treatment (250 µg on day 2) of WT recipients resulted in moderate prolongation of allograft survival compared to untreated WT control (MST of 41 vs. 7 days, respectively, *p < 0.05, t-test), PI3Kγ −/− recipients treated with a single dose CTLA4-Ig showed indefinite prolongation of heart allograft survival (MST of >100 vs. 41 days, respectively, *p < 0.05, t-test, n = 7–10/group) (Fig. 3a). However, PI3Kδ D910A/D910A recipients treated with single dose CTLA4-Ig showed relatively shorter heart allograft survival compared to WT recipients (MST of 32 vs. 41 days, respectively, *p < 0.05, t-test, n = 7–10/group) (Fig. 3a). Histological examination of heart allografts (harvested at day 100 post-transplant) showed minimal signs of rejection in the PI3Kγ −/− + single dose CTLA4-Ig group as compared to WT + single dose CTLA4-Ig group (heart allografts harvested at day 28 post-transplant) (Fig. 3b). PI3Kγ −/−+single dose CTLA4-Ig recipients also showed fewer CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in heart grafts harvested at day 28 post-transplant compared to WT + single dose CTLA4-Ig group. (*p < 0.05, t-test, n = 6/group) (Fig. 3c). However, histological examination of heart allografts harvested at day 28 post-transplant showed massive cell infiltration in the PI3Kδ D910A/D910A recipients treated with single dose CTLA4-Ig as compared to WT recipients treated with single dose CTLA4-Ig (Fig. 3d).

Fig. 3.

PI3Kγ or PI3Kδ deletion and long-term allograft survival. a single dose CTLA4-Ig, injected into PI3Kγ −/− recipients induced long-term acceptance of fully mismatched BALB/c cardiac allografts compared to the controls (MST of 41 vs. >100 days, *p < 0.05, t-test, n = 10/group). However, single dose CTLA4-Ig, injected into PI3Kδ D910A/D910A recipients of fully mismatched BALB/c cardiac allografts showed reduced allograft survival compared to the controls (MST: 41 vs. 32 days, *p < 0.05, t-test, n = 7–10/group). b Representative examples of cardiac allograft histology at day 100 post-transplant show lower grades of acute cellular rejection in the PI3Kγ −/− hearts treated with single dose CTLA4-Ig compared to cardiac allograft at day 28 post-transplant from WT mice treated with single dose CTLA4-Ig (n = 4/group). Inset show worse vasculopathy in the WT recipients treated with single dose CTLA4-Ig compared to PI3Kγ −/− hearts treated with single dose CTLA4-Ig (H&E stain, scale bar 50 μm, inset scale bar 25 μm). Immunohistochemistry analysis of CD3 and FoxP3 shows fewer CD3+ infiltrating cells in the PI3Kγ −/− hearts treated with single dose CTLA4-Ig compared to WT but relatively more FoxP3 (scale bar 50 μm). c Representative dot plots of leukocytes isolated from the allograft of PI3Kγ −/− and WT recipients treated with single dose CTLA4-Ig show significantly less CD4+ and CD8+ infiltration in the PI3Kγ −/− allografts compared to WT. Bar graph represents the absolute count of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the heart allografts of PI3Kγ −/− and WT recipients treated with single dose CTLA4-Ig. (*p < 0.05, t-test, n = 6/group, the graphs show data as mean ± s.e.m.). d Representative examples of cardiac allograft histology at day 28 post-transplant show higher grades of acute cellular rejection in the PI3Kδ D910A/D910A hearts treated with single dose CTLA4-Ig compared to WT mice treated with single dose CTLA4-Ig (n = 4/group). Inset show more severe vasculitis in the PI3Kδ D910A/D910A treated with single dose CTLA4-Ig compared to WT-recipient hearts treated with single dose CTLA4-Ig (H&E stain, scale bar 50 μm, inset scale bar 25 μm). (MST mean survival time)

PI3Kγ −/− + single dose CTLA4-Ig recipients also showed significant suppression of CD4+ and CD8+ effector T cells in the secondary lymphoid tissue as compared to control mice (Supplementary Fig. 4A, B). A significant reduction in T cell proliferative responses and in the level of inflammatory cytokines IFNγ and interleukin (IL)-6 were also noted in PI3Kγ −/− + single dose CTLA4-Ig recipients (Supplementary Fig. 4C–E). These data indicate that the inhibition of PI3Kγ selectively suppresses alloreactive T cells.

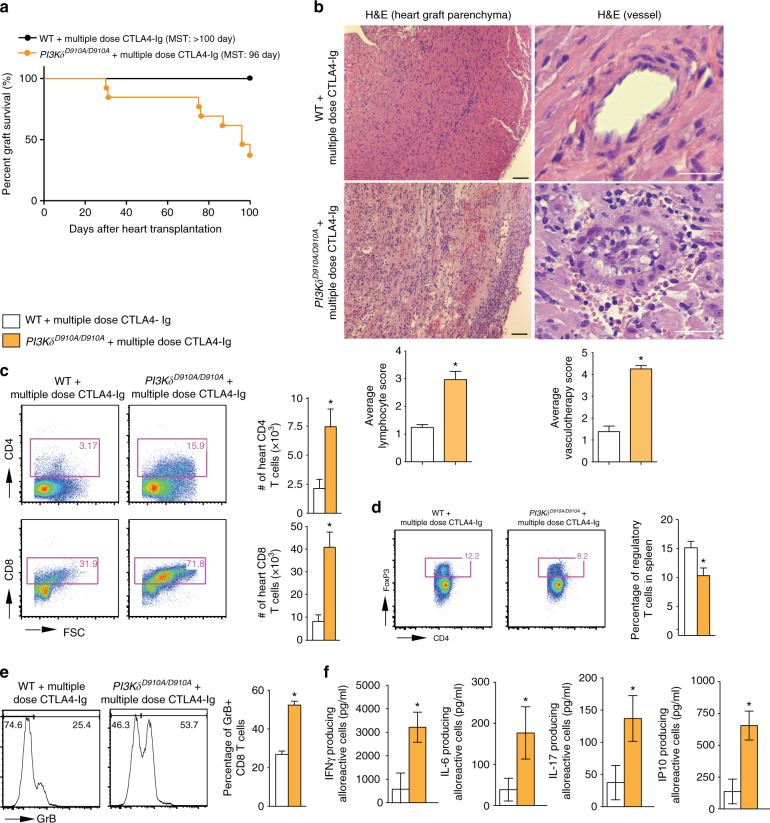

PI3Kδ deletion abrogates the tolerogenic effect of CTLA4-Ig

We then escalated the dose of CTLA4-Ig to induce indefinite allograft survival in WT recipients. Multiple dose CTLA4-Ig treatment (500 µg on day 0 then 250 µg on day 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10) of WT recipients resulted in indefinite prolongation of heart allograft survival compared to the untreated WT control (MST of >100 vs. 7 days, respectively, *p < 0.05, t-test). However, PI3Kδ D910A/D910A + multiple dose CTLA4-Ig group showed significantly earlier rejection as compared to WT recipients (MST of >100 vs. 96 days, respectively, *p < 0.05, t-test, n = 10/group) (Fig. 4a). Heart allografts from PI3Kδ D910A/D910A + multiple dose CTLA4-Ig treated mice recovered at day 100 post-transplant showed much more severe chronic rejection with lymphocyte infiltration and vasculopathy (Fig. 4b). Average scores for lymphocyte infiltration and vasculopathy were higher in PI3Kδ D910A/D910A + multiple dose CTLA4-Ig group compared to control (Fig. 4b below the H&E pictures) with increased intima-media thickness (Supplementary Fig. 5). PI3Kδ D910A/D910A + multiple dose CTLA4-Ig group showed significantly greater CD4+ and CD8+ infiltration of the allografts compared to WT + multiple dose CTLA4-Ig group (*p < 0.05, t-test, n = 6/group) (Fig. 4c). Furthermore, a significantly lower percentage of Tregs was observed in the spleen of treated PI3Kδ D910A/D910A mice compared to treated WT (*p < 0.05, t-test, n = 6/group) (Fig. 4d). A much higher number of CD8+ effector T cells were also observed in the secondary lymphoid organs of treated PI3Kδ D910A/D910A mice compared to treated WT (*p < 0.05, t-test, n = 6/group) (Supplementary Fig. 6). Interestingly, splenic CD8+ CD44high T cells from PI3Kδ D910A/D910A mice showed much higher expression of Granzyme B (GrB) as compared to WT recipients, as measured by flow cytometry (52.38% ± 2.0% vs. 26.83% ± 1.77%, respectively, *p < 0.05, t-test, n = 4/group) (Fig. 4e). Finally, PI3Kδ D910A/D910A recipient splenocytes also significantly increased inflammatory cytokine and chemokine production upon stimulation by irradiated donor cells, as measured by luminex assay (*p < 0.05, t-test, n = 4/group) (Fig. 4f).

Fig. 4.

PI3Kδ deletion abrogates the tolerogenic effect of CTLA4-Ig. a Multiple dose CTLA4-Ig treatment of PI3Kδ D910A/D910A recipients abrogates the long-term acceptance of fully mismatched BALB/c cardiac allografts seen in treated WT controls (MST of > 100 vs. 96 days, *p < 0.05, t-test, n = 10/group). b Representative examples of cardiac allograft histology harvested 100 days after transplant show higher grades of cellular infiltration (H&E stain, scale bar 50 μm) and vasculopathy (H&E stain, scale bar 25 μm) in the PI3Kδ D910A/D910A hearts treated with multiple dose CTLA4-Ig compared to WT mice treated with multiple dose CTLA4-Ig (n = 4/group). The bar graphs show the average of lymphocyte infiltration score and vasculopathy score. The PI3Kδ D910A/D910A hearts treated with multiple dose CTLA4-Ig shows significantly higher score compared to WT mice treated with multiple dose CTLA4-Ig (*p < 0.05, t-test, n = 4/group, the graphs show data as mean ± s.e.m.). c Representative examples of dot plots of leukocytes isolated from the allograft of PI3Kδ D910A/D910A and WT recipients treated with multiple dose CTLA4-Ig shows more CD4+ and CD8+ infiltration in the allografts of PI3Kδ D910A/D910A recipients compared to WT control. Graph represents the absolute count of graft-infiltrating CD4 and CD8 in PI3Kδ D910A/D910A recipients treated with multiple dose CTLA4-Ig compared to WT control treated with multiple dose CTLA4-Ig (*p < 0.05, t-test, n = 6/group). d Representative examples of dot plots of Tregs in the DLN of PI3Kδ D910A/D910A and WT recipients treated with multiple dose CTLA4-Ig show significantly fewer Tregs in the PI3Kδ D910A/D910A recipients compared to WT control (*p < 0.05, t-test, n = 6/group). e Representative examples of histograms of GrB expression by CD8+ CD44high T cells in the spleen of PI3Kδ D910A/D910A and WT recipients treated with multiple dose CTLA4-Ig show significantly more GrB expression in CD8+ of the PI3Kδ D910A/D910A recipients compared to WT (*p < 0.05, t-test, n = 4/group). f WT and PI3Kδ D910A/D910A recipient splenocytes were stimulated with donor splenocytes. Bar graphs represent the level of IFNγ, IL-6, IL-17, and IP10 in the supernatant collected from the MLR assay as measured by luminex (*p < 0.05, t-test, n = 4/group). c–f The graphs show data as mean ± s.e.m. (MST mean survival time; DLN draining lymph node; Treg regulatory T cell; GrB GranzymeB)

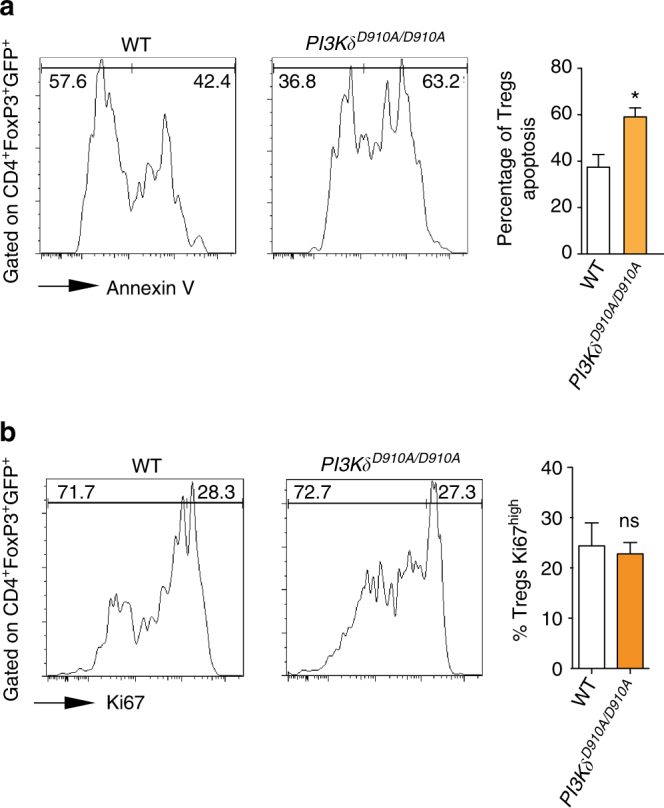

PI3Kδ deletion reduces Treg survival

Two groups of lethally irradiated BALB/c mice were reconstituted with 2 × 106 CD3+CD25− T cells derived from WT C57BL/6 (Thy1.1) mice. Mice were co-injected with 1 × 106 WT and PI3Kδ D910A/D910A natural regulatory T cells (nTreg) (Thy1.2). As shown in Fig. 5a, flow cytometric analysis of splenocytes showed that PI3Kδ D910A/D910A nTregs had higher rate of apoptosis compared to WT nTregs (*p < 0.05, t-test, n = 3/group). No difference was seen in the proliferation of the transferred WT and PI3Kδ D910A/D910A nTregs as measured by Ki67 using flow cytometry. (p = ns, t-test, n = 3/group) (Fig. 5b).

Fig. 5.

PI3Kδ inhibition abrogates Treg survival. a Representative examples of Annexin staining of WT and PI3Kδ D910A/D910A nTregs transferred in the spleen of C57BL/6 mice induced with GVHD. Bar graph represents the different percentages. (*p < 0.05, t-test, n = 3/group). b Representative examples of Ki67 expression of WT and PI3Kδ D910A/D910A nTregs transferred into C57BL/6 mice induced with GVHD. Bar graph represents the different percentages. (*p < 0.05, t-test, n = 3/group). a, b The graphs show data as mean ± s.e.m. (Treg regulatory T cell; GVHD graft vs. host disease; nTreg natural regulatory T cell)

PI3Kγ deletion protects from chronic rejection

Chronic rejection remains a major cause of graft failure in clinical solid organ transplants25, 26. We next investigated the role of PI3Kγ inhibition in chronic rejection using class II MHC-mismatch heart transplant model (B6.H-2bm12 donor hearts into C57BL/6 recipient). Heart allografts recovered from PI3Kγ −/− recipients day 28 showed significantly less infiltration, fibrosis and intima-medial thickness as compared to WT recipients (Supplementary Fig. 7).

PI3Kδ deletion has no effect on FoxP3 methylation

We assessed the expression of the genes controlling the FoxP3 promoters and the status of FoxP3 demethylation on multiple CpG motifs of the first intron of FoxP3, which have been shown to control its transcription27, 28. We performed quantification analysis of the FoxP3 gene methylation at the five CpG sites of the proximal promoter known to control its transcription (location: −6750 to −6714 from ATG) in WT and PI3Kδ D910A/D910A Tregs at 24 h post stimulation. Our analysis did not show any statistically significant difference between the different groups (Supplementary Fig. 8). Total percent methylation for in WT and PI3Kδ D910A/D910A were 58.3 ± 6.6 and 59.29 ± 11.2, respectively, (p = 0.8, t-test, n = 4/group).

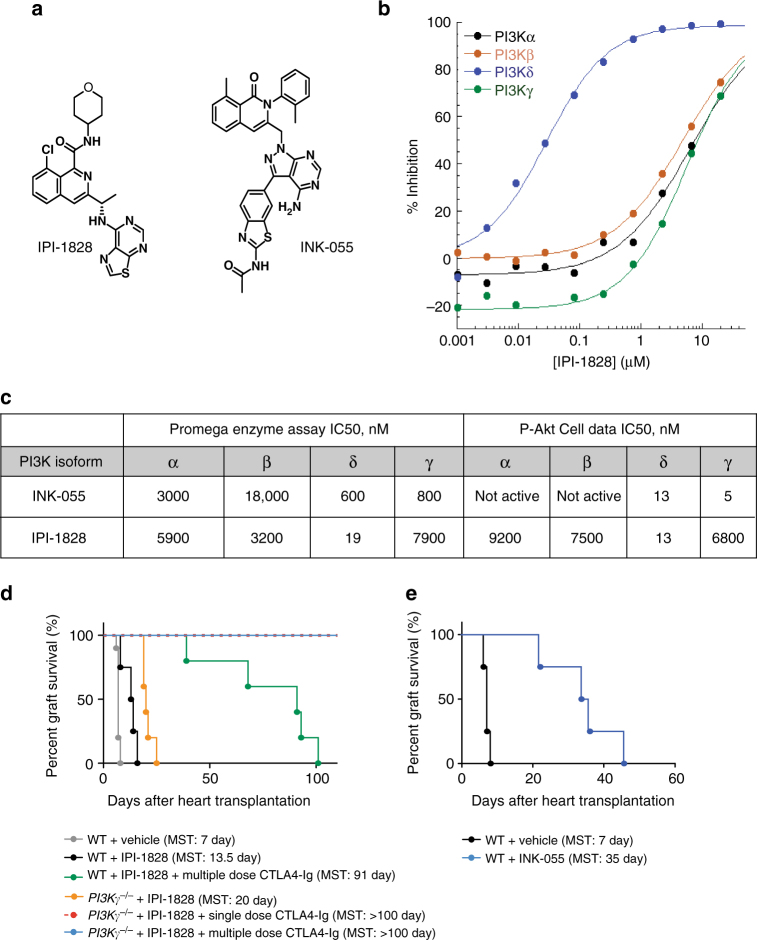

Generation of PI3Kδ and PI3Kγδ selective inhibitors

To examine the effect of pharmacologic inhibition of PI3K isoforms, the selective inhibitors IPI-1828 and INK-055 were synthesized and utilized in our transplant model. To mimic the high ATP concentrations found within cells, IPI-1828 and INK-055 were evaluated in PI3K isoform specific biochemical assays in the presence of 3 mM ATP. IPI-1828 is a PI3Kδ selective inhibitor with activity against the targeted isoform of 19 nM against PI3Kδ and 5900, 3200, and 7900 nM against PI3Kα, PI3Kβ, and PI3Kγ, respectively. IPI-1828 was evaluated in isoform selective cell based assays with a 13 nM IC50 of the phosphorylation of AKT (S473) in the PI3Kδ selective assay, and greater than 200-fold less activity in the PI3Kα, PI3Kβ, and PI3Kγ isoform selective cell based assays. INK-055 is a previously characterized PI3K-inhibitor that has potent cellular activity against PI3Kδ and PI3Kγ with IC50s of 13 and 5 nM, respectively, (Fig. 6a–c) and is a dual PI3Kγδ inhibitor in animal models29.

Fig. 6.

Synthesis of new PI3K δ and γδ inhibitor. The characterization of IPI-1828, a PI3Kδ selective compound, and INK-055, a PI3Kγδ inhibitor. a The chemical structure of IPI-1828 and INK-055. b Isotherms of IPI-1828 inhibitory activity in enzymatic assays for Class 1 PI3Ks were determined by monitoring the hydrolysis of ATP with a luminescence-based end point assay as described in methods section. This assay was run in the presence of 3 mM ATP and 500 uM PIP2 substrates. The ATP concentration of 3 mM was used to more to closely resemble cellular concentrations. c Summary of IC50s in a biochemical assay run in the presence of 3 mM ATP, and isoform selective cell-based assays for class 1 PI3Ks. d Synergism of PI3Kδ and PI3Kγ inhibition in prolonging allograft survival. Kaplan–Meier survival of heart allografts in WT and PI3Kγ −/− recipients treated with PI3Kδ inhibitor (IPI-1828) and single dose CTLA4-Ig or multiple dose CTLA4-Ig. (n = 5/group). e Kaplan–Meier survival of heart allograft in WT recipients treated with PI3Kγδ inhibitor (INK-055) showed significant prolongation of heart allograft survival compared to control (MST of 35 vs. 7 days, *p < 0.05, t-test, n = 5/group). (MST mean survival time)

Synergistic effect of PI3Kγ and PI3Kδ inhibition

We then tested whether the presence of PI3Kγ inhibition would rescue the deleterious effect of PI3Kδ inhibition and whether there is synergism in further prolonging heart allograft survival. Naive BALB/c allografts were transplanted into WT C57BL/6 recipients and treated with a specific PI3Kδ inhibitor (IPI-1828: 50 mg/kg twice daily via gavage day 0 to 6). As shown in Fig. 6d, WT recipients treated with PI3Kδ inhibitor (IPI-1828) exhibited prolonged allograft survival compared to the WT recipients treated with vehicle only (MST of 13.5 vs. 7 days, respectively, *p < 0.05, t-test, n = 5/group). However, mice treated with dual PI3Kγδ inhibitor (INK-055: 100 mg/kg daily, day 0 to 6) exhibited an additional allograft survival compared to either the WT recipients treated with PI3Kδ inhibitor (IPI-1828) or vehicle only (MST of 35 vs. 13.5 vs. 7 days, respectively, *p < 0.05, t-test, n = 5/group) (Fig. 6d, e). Furthermore, PI3Kγ –/– recipients treated with PI3Kδ inhibitor (IPI-1828) exhibited a significantly prolonged allograft survival compared to the PI3Kγ –/– recipients treated with vehicle only (MST of 20 vs. 11 days, respectively, *p < 0.05, t-test, n = 5–10/group) (Fig. 6d). Interestingly, while PI3Kδ inhibitor (IPI-1828) abrogated the tolerogenic effect of multiple dose CTLA4-Ig on WT C57BL/6 recipients of BALB/c hearts (MST of 91 days), adding PI3Kδ inhibitor (IPI-1828) to PI3Kγ –/– recipients treated with single or multiple dose CTLA4-Ig induced indefinite heart allograft survival and did not abrogate tolerance (Fig. 6d).

Discussion

To study the role of PI3Kγ and PI3Kδ in alloimmunity, first we showed that PI3Kγ −/− and PI3Kδ D910A/D910A T cells have impaired alloimmune reactivity; demonstrating suppressed alloreactive T cell proliferative responses coupled with a reduction in the frequency of IFNγ producing alloreactive cells in vitro. These findings were confirmed in vivo in an adoptive transfer model. These data are in accordance with previously published work showing that, along with activation via G protein coupled receptors, TCR cross-linking with anti-CD3 Abs also activates p110γ and induces its association with lck and ZAP70, resulting in T cell activation14. PI3Kδ is also downstream of TCR and its absence from this pathway explains the T cell defect observed in vitro and in vivo. However, PI3Kδ deletion had a significant deleterious effect on regulatory T cell (Treg) induction.

Prolongation of heart allograft survival in PI3Kγ −/− recipients was associated with a marked suppression of alloreactive T cells in a model of acute heart allograft rejection. Accumulating experimental data point to the importance of targeting innate immunity and inflammation to improve transplant outcomes, particularly to prevent the development of chronic rejection, which remains one of the main barriers to long term allograft survival30–35. PI3Kγ −/− recipients showed a notable decrease in inflammatory cytokines known to play a key role in the pathogenesis of chronic rejection36, 37. This reduction in inflammatory cytokines may, in part, explain the marked reduction in chronic rejection noted in the PI3Kγ −/− recipients.

One of our key findings was that the inhibition of PI3Kδ effectively suppressed alloreactive T effectors while it also reduced Tregs. The balance of Tregs to T effectors is well established as a key determinant of the long-term outcome of transplantation. Similar to PI3Kγ inhibition, PI3Kδ inhibition prolonged allograft survival in an acute heart allograft rejection model with significant suppression of effector CD4+ and CD8+ T cells post-transplantation. However, to study the impact of PI3Kδ signaling on the maintenance of long-term tolerance via its effect on Treg homeostasis, we used a combinatorial strategy, treating PI3Kδ D910A/D910A recipients with single dose CTLA4-Ig. In this long-term transplantation model, graft survival is dependent on the presence of Tregs. PI3Kδ inhibition abrogated the tolerogenic effect of CTLA4-Ig with a significant reduction in Tregs. This decrease in Tregs may explain the upregulation of the CD8+ T effector cells in PI3Kδ D910A/D910A recipients and the observed increase in allograft-infiltrating inflammatory cells.

We then investigated whether this reduction in Tregs in the periphery is due to decreased proliferation or increased apoptosis. Transfer of natural Tregs (nTreg) from WT, and PI3Kδ D910A/D910A mice into an allogeneic host showed a higher rate of PI3Kδ D910A/D910A nTreg apoptosis compared to WT nTregs. No difference in proliferation was observed between the different groups, as assessed by Ki67 expression of transferred Tregs. Our data is in accordance with previous work by Ali et al.38, where p110δ inhibition induced a Treg defect, leading to tumor regression through enhanced CD8 cytotoxic T cell activity.

We also investigated the mechanisms responsible for the deleterious effect of PI3Kδ on Treg induction. The transcriptional activity of the CpG-motif containing element of the FoxP3 first intron, which is located within TSDR (Treg-specific demethylated region) is known to be methylation-sensitive. Methylation of this island inversely correlates with CREB binding and FoxP3 expression28. Furthermore, DNA methylation in TSDR has been shown to be critically involved in maintaining stable FoxP3 expression39. We observed no differences in the demethylation of the FoxP3 gene in PI3Kδ D910A/D910A CD4+ Tregs.

Currently, the importance of PI3K pathways in the development of Tregs is under intense investigation40, and dramatic anti-tumor effects have been seen in trials using PI3Kδ inhibition in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia41. This effect has been ascribed to the inhibition of Treg in these patients and our data are in concordance with these findings.

Altogether, our data indicate that the inhibition of PI3Kγ and PI3Kδ both restrict the expansion of alloreactive T cells, however, PI3Kδ has a counter-regulatory effect on the homeostasis of Treg. Recent studies have highlighted the potential importance of the level of AKT (activated by the PI3K pathway) on the fate of Treg and differentiation of effector T cells42, 43. Modulation of AKT activity in Treg is essential for their optimal function and excessive AKT activation has been shown to be detrimental to their suppressive activity40, 44, 45.

On the other hand, upon TCR activation, rapidly dividing CD8+ cells demonstrate high AKT activity levels. Effector T cells with high PI3K/AKT activity are resistant to the suppressive effects of Tregs46, 47. Using mice deficient for PTEN (natural inhibitor of PI3K) in Treg, Turka’s group has shown a change in the metabolic programming of Treg and decline in their stability48. Future studies are required to better define the relative contribution of PI3Kδ on controlling the balance of Teff/Treg via regulation of metabolic programming.

Finally, we have generated a PI3Kδ inhibitor (IPI-1828) and a dual PI3Kγδ inhibitor (INK-055). PI3Kδ inhibition has already entered the clinic with success, though synthesizing a PI3Kγ inhibitor has proved a more daunting task. In our studies, both PI3Kγ and PI3Kδ inhibition suppressed alloreactive T cells; therefore, an important question to address was the importance of combinatorial therapy in prolonging heart allograft survival. Dual inhibition showed a further suppression of alloimmune responses and restored the tolerogenic effect of CTLA4-Ig in the presence of PI3Kδ inhibition. Dual inhibition of PI3Kγ and δ has also previously been shown to have superior anti-inflammatory effects10. Our data indicate that PI3Kγ inhibition rescues the negative effect of PI3Kδ inhibition on long-term allograft survival and identifies dual PI3Kγ and δ inhibition as a promising and novel platform to pursue in future studies with large animals.

A role for PI3Kγ inhibition in modifying the activity of tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells toward a pro-inflammatory phenotype, leading to increased anti-tumor activity and reduced tumor growth has recently been reported49, 50. The contrasting findings observed here could be due to differences between our allogeneic transplant model versus syngeneic tumor models. In heart transplant models, rejection is predominantly a T cell mediated process51. Myeloid cells do not constitute the majority of infiltrating cells during rejection. Our T cell data is in accordance with multiple other publications showing a direct role for PI3Kγ inhibition in T cell suppression12–14, 52–54. Chronically immunosuppressed patients suffer from increased risk of malignancy and the capacity of PI3Kγ to potentially both prevent rejection and have anti-tumor activity renders it an extremely attractive target for clinical translation.

The field of transplantation has an ongoing unmet need for more selective and effective immunomodulatory molecules to improve transplantation outcomes. PI3Kγδ inhibitors are being clinically studied for other immune-mediated diseases and our data indicate that these molecules also hold significant promise in controlling alloimmune activation, and show particularly impressive effects in the prevention of chronic allograft rejection, a major cause of late allograft loss. Further studies are required to fully evaluate their potential role in clinical transplantation.

Methods

Mice and reagents

C57BL/6J (JAX#000664), BALB/cByJ (H-2d) (JAX#001026), B6.C-H2bm12/KhEg (bm12) (JAX#001162), Foxp3GFP knock-in mice on a C57BL/6 background (JAX#023800) and Rag −/− mice (JAX#002216) were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. PI3Kγ −/− C57BL/6 mice (backcrossed 11 generations) were received from Dr Bao Lu (Boston Children’s Hospital/ Harvard Medical School) and maintained in our animal facility55. p110D910A C57BL/6 (PI3Kδ D910A/D910A) mice were obtained from Charles River Laboratory56. PI3Kγ −/− C57BL/6 and p110D910A C57BL/6 (PI3Kδ D910A/D910A) mice were also backcrossed with FoxP3GFP knock-in mice in our facility. Male or female mice were used at 6–10 weeks of age (20–25 g) and were housed in sterilized ventilated cages in a specific pathogen-free animal facility under standard 12 h light/12 h dark cycle. Mice were fed ad libitum irradiated food and water. Each individual experiments was done using three to ten mice per group. Mice were euthanized by either CO2 inhalation, intraperitoneal injection of ketamine/xylazine or isoflurane inhalation followed by observation of loss of vital signs and cervical dislocation. All animal experiments and methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

Murine cardiac transplantation

Vascularized intra-abdominal heterotopic transplantation of cardiac allografts was performed using microsurgical techniques as described previously57. Briefly, 1 ml of cold heparin (BD Vacutainer Sodium Heparin #366480 143USP units/10 ml) was infused into the inferior vena cava of the donor mouse. Hearts were harvested following the ligation/dissection of superior vena cava and inferior vena cava and dissection of ascending aorta and pulmonary artery. Harvested donor hearts were stored at 4 degrees celsius, immersed in UW (University of Wisconsin) solution until transplantation. After abdominal incision of recipient mouse, abdominal aorta and inferior vena cava were clamped. Ascending aorta and pulmonary artery of donor heart were attached to abdominal aorta and inferior vena cava of recipient mouse, respectively, using 10–0 suture. Beating of transplanted heart was observed upon removal of cross clamp, and abdominal incision was closed. The survival of cardiac allografts was assessed by daily palpation. Rejection was defined as complete cessation of cardiac contractility as determined by direct visualization and confirmed by histology.

Skin transplantation

Full-thickness trunk skin grafts (1 cm2) harvested from BALB/c donors were transplanted onto the flank of Rag −/−-recipient mice, sutured with 6–0 silk, and secured with dry gauze and a bandage for 7 days.

Histological and immunohistochemical assessment

Five micron thick formalin fixed paraffin embedded sections were stained with standard Hematoxylin and Eosin stain (H&E), CD3 stain, Foxp3 stain, Elastic Van Gieson stain and F4/80 stain. Histological evaluation was done using a score modified from the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation58, 59. Lymphocyte infiltration is graded 0 to 4 at 6 random fields of each heart H&E section blindly by two individual researchers (six sections/heart, three mice per group). The grades are defined as follows: grade 0 (no lymphocyte infiltration), grade 1 (less than 25% lymphocyte infiltration), grade 2 (25 to 50% lymphocyte infiltration), grade 3 (50 to 75% lymphocyte infiltration), and grade 4 (more than 75% lymphocyte infiltration and myocyte hemorrhage). Vascular score is determined by a combination of vascular occlusion score and perivascular lymphocyte infiltration. Vascular occlusion is scored from grade 0 to 4 for every vessel (six sections/heart, three mice per group). The grades are defined as follows: grade 0 (no occlusion), grade 1 (less than 50% occlusion), grade 2 (50 to 75% occlusion), grade 3 (75 to 95% occlusion) and grade 4 (more than 95% occlusion). The perivascular lymphocyte infiltration is scored as described above and was then added to the vascular occlusion score.

Isolation of lymphocytes from hearts

Cardiac allografts were removed, perfused with PBS, minced finely with a razor blade and digested at 37 °C with 1 mg/ml collagenase in 1 ml complete medium for 1 h. Cells in the supernatant were washed twice, centrifuged at 620xg using Percoll solutions at 33% (cell suspension) and 66%. Lymphocytes were aspirated at the interface.

Treg generation assay

Using a 96-well flat bottom plate, 100 μl of anti-CD3 antibody (Ab) diluted in PBS (1 μg/ml, BD Biosciences) was added to each well and incubated at 37 °C for 4 h. In all, 1 μg/ml of anti-CD28 Ab, 10 ng/ml of IL-2 and soluble recombinant human TGFβ (1 ng/ml, R&D Systems) was then added to each well in the presence of 2.5 × 104 CD4+CD25− T cells of C57BL/6 or PI3Kγ −/− mice.

CD3/CD28 T cell stimulation and MLR assays

Using a 96-well flat bottom plate, 100 μl of anti-CD3 Ab and soluble anti-CD28 Ab (1 μg/ml, BD Biosciences) was used in the presence of C57BL/6 or PI3Kγ −/− splenocytes. For the MLR assay, irradiated wild type (WT) BALB/c splenocyte stimulators and WT C57BL/6 or PI3Kγ −/− splenocyte responders were added to each well in a 96-well round bottom plate pulsed with 1 μCi of tritiated thymidine (3H) and the incorporation efficiency was determined.

ELISpot

ELISpot assays were performed with WT BALB/c splenocytes as stimulators and WT C57BL/6 or PI3Kγ −/− splenocytes as responders, as described previously60. Briefly, 5 × 105 each of irradiated stimulating cells and responders were added to each well of Millipore Immunospot plates (Millipore Corporation, Bedford, MA). Biotinylated antibodies specific for each cytokine were added to the wells and incubated. The plates were developed and spots were counted on an Immunospot analyzer (Cellular Technology Ltd., Cleveland, OH).

Flow cytometric analysis

Anti-mouse monoclonal antibodies against CD62L (1:400 diluted, MEL-14, 560516), CD44 (1:400 diluted, IM7, 103027), CD4 (1:400 diluted, RM4-5, 100559), CD25 (1:400 diluted, PC61.5, 12-0251-81B), CD8 (1:400 diluted, 53-6.7, 100734), FoxP3 (1:300 diluted, FJK-16s, 11-5773-82), GrB (1:100 diluted, KGZB, 12-8898-82), H2Kb (1:100 diluted, SF1-1.1, 553565), thy1.2 (1:100 diluted, 53-2.1, 17-0902-83), Annexin PE (51-65875X), 7 AAD PerCP (51-68981E), Ki67 (1:300 diluted, SolA15, 11-5698-82), cRel (1:300 diluted, IRELAHS, 12-6111-80) were purchased from BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA. Cells recovered from spleens and peripheral lymphoid tissues were interrogated with a FACS Canto-II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo software version 9.3.2 (Treestar, Ashland, OR). Para-aortic lymph nodes from host were harvested as secondary lymphoid organs or draining lymph nodes (DLN) of the heart allografts. Gating strategies for lymphocyte subpopulations are shown in Supplementary Fig. 9.

Luminex assay

A 21-plex cytokine-kit (Millipore, St Charles, MO) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions to assess cytokine production in culture supernatant and in murine serum samples.

CFSE labeling

Spleen and peripheral lymph nodes were recovered from C57BL/6 (WT) and PI3Kγ −/− mice, and a single cell suspension was prepared in HBSS. Red blood cells were lysed with ACK buffer and cells were suspended in Hanks’ Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) at 1 × 107 cells/ml for labeling with CFSE (Molecular Probes, Portland, OR). Briefly, cells were incubated with CFSE at a final concentration of 5 μM in serum-free HBSS at room temperature for 6 min The labeling reaction was then terminated by the addition of FCS (10% of the total volume). Cells were then washed twice in HBSS and used for in vitro experiments.

FoxP3 gene demethylation analysis

For DNA demethylation analysis, 500 ng of extracted genomic DNA was bisulfite treated and purified according to the manufacturer’s protocol. PCRs were performed using 1 μl of bisulfite treated DNA and 0.2 μM of each primer. PCR products were sequenced by Pyrosequencing on the PSQ96 HS System (Pyrosequencing, Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The methylation status of each CpG site was determined individually as an artificial C/T SNP using QCpG software (Pyrosequencing, Qiagen). The methylation level at each CpG site was calculated as the percentage of the methylated alleles divided by the sum of all methylated and unmethylated alleles. The mean methylation level was calculated using methylation levels of all measured CpG sites within the targeted region of each gene. Each experiment included non-CpG cytosines as internal controls to detect incomplete bisulfite conversion of the input DNA. In addition, a series of unmethylated and methylated DNA are included as controls in each PCR. Furthermore, PCR bias testing was performed by mixing unmethylated control DNA with in vitro methylated DNA at different ratios (0, 5, 10, 25, 50, 75, and 100%), followed by bisulfite modification, PCR, and Pyrosequencing analysis. CPG sites analyzed for the FoxP3 gene were CpG 64–68 of the proximal promoter.

PI3K inhibitors

IPI-1828 (PI3Kδ inhibitor) was prepared according the methods in US Patent No. 8,901,133 Example 85 and was obtained from Infinity Pharmaceuticals, Inc. INK-055 (PI3Kγδ inhibitor) was prepared as described29 and was obtained from Infinity Pharmaceuticals, Inc. IPI-1828 was stored as a 10 mM stock in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at room temperature. All human PI3K isoforms were purchased from Millipore (Billerica, MA).

Biochemical IC50 determinations

IC50 values for all PI3K isoforms were determined by measuring the dose-dependent decrease in luminescent signal with increasing concentrations of IPI-1828. PI3K was incubated for 15 min with increasing concentrations of IPI-1828 followed by addition of ATP to 3 mM concentration and 500 μM diC8PIP2 substrates. Reactions were incubated at room temperature for 2 h. Detection of PI3K activity was then carried out using the ADP-Glo Max Assay Kit. Enzyme concentrations of 10 nM were used for the PI3Kα and PI3Kδ isoforms, and 40 nM for PI3Kβ and PI3Kγ isoforms. IC50 measurements were calculated as described previously61.

PI3Kα assay design/PI3Κβ assay design

SKOV-3 cells (ATCC HTB-77) for PI3Kα assay design and 786-O cells for PI3Kβ assay design were seeded into 96-well cell culture grade plates at a density of 200,000 cells/200 μl/well of RPMI-1640 with 10% FBS. Cells were incubated overnight at 5% CO2 and 37 °C. IPI-1828 or INK-055 (diluted in 25% DMSO in threefold dilutions from 10 μM to generate an 11 and 9 point titration curve, respectively) was added to the cells, resulting in a final DMSO concentration of 0.5%, and incubated for 30 min at 5% CO2 and 37 °C.

PI3Kγ assay design

RAW 264.7 cells were seeded into 96-well cell culture-grade plates at a density of 200,000 cells/200 μl/well of DMEM with no FBS added. Cells were incubated overnight at 5% CO2 and 37 °C. Following 18 h of serum-starvation, IPI-1828 or INK-055 (diluted in 25% DMSO in threefold dilutions from 0.2 μM to generate a 9-point titration curve) was added to the cells, resulting in a final DMSO concentration of 0.5%, and incubated for 30 min at 5% CO2 and 37 °C. Cells were then stimulated with 25 nM C5a for 3 min in the presence of IPI-1828 or INK-055.

PI3Kδ assay design

RAJI cells were seeded into 96-well cell culture-grade plates at a density of 200,000 cells/200 μl/well of RPMI-1640 with no FBS added. Cells were incubated overnight at 5% CO2 and 37 °C. Following 18 to 24 h of serum-starvation, IPI-1828 or INK-055 (diluted in 25% DMSO in threefold dilutions from 10 μM to generate an 11-point titration curve) was added to the cells, resulting in a final DMSO concentration of 0.5%, and incubated for 30 min at 5% CO2 and 37 °C. Cells were then stimulated with 10 μg/ml anti-human IgM for 30 min in the presence of IPI-1828 or INK-055.

Media was aspirated and 50 μl/well of ice-cold lysis buffer was added. Plates were incubated on ice for 5 min and then centrifuged at 3000 rpm at 4 °C for 5 min Phospho AKT ELISA and analysis were as described for each isoform61.

Pharmacokinetics

The pharmacokinetics and oral bioavailability of IPI-1828 in C57BL/6 mice were studied following a single intravenous and oral doses. Blood samples were collected prior to dose administration (oral dose only) and at time points post-treatment. The blood samples were processed to plasma and assayed for IPI-1828 using a liquid chromatography method with tandem mass spectrometric (LC-MS/MS) detection. Pharmacokinetic parameters were determined using standard non-compartmental methods61.

Statistics

Kaplan–Meier survival curves were constructed, and a log rank comparison of the groups was used to calculate p-values. The unpaired t-test was used for comparison of experimental groups examined by ELISpot, ELISA, luminex, flow cytometry, and MLR. Differences were considered to be significant for p < 0.05. Prism software was used for data analysis and drawing graphs (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA). Data represent mean ± s.e.m.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are available from the author on reasonable request.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by American Heart Association Grant (to J.A.) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number RO1AI126596 and R56AI123270 (R.A.).

Author contributions

M.U. performed experiments, microsurgery and analyzed data, and drafted the manuscript. M.M. designed experiments, interpreted data and drafted the manuscript. S.O. performed experiments and microsurgery. Z.S., N.B., S.R., and A.E. performed experiments. C.E., J.D., and D.W. developed IPI-1828 and INK-055, designed and performed PI3Kγ and δ assay. L.T., T.S., and S.T. helped with study design. J.A. and R.A. designed the study, interpreted data, analyzed data, and critically revised and finalized the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00982-x.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kobashigawa JA. The future of heart transplantation. Am. J. Transplant. 2012;12:2875–2891. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nankivell BJ, Alexander SI. Rejection of the kidney allograft. N. Eng. J. Med. 2010;363:1451–1462. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0902927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kobashigawa JA, Patel JK. Immunosuppression for heart transplantation: where are we now? Nat. Clin. Pract. Cardiovasc. Med. 2006;3:203–212. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio0510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walker EH, Perisic O, Ried C, Stephens L, Williams RL. Structural insights into phosphoinositide 3-kinase catalysis and signalling. Nature. 1999;402:313–320. doi: 10.1038/46319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruckle T, Schwarz MK, Rommel C. PI3Kgamma inhibition: towards an ‘aspirin of the 21st century’? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2006;5:903–918. doi: 10.1038/nrd2145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vanhaesebroeck B, Ali K, Bilancio A, Geering B, Foukas LC. Signalling by PI3K isoforms: insights from gene-targeted mice. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2005;30:194–204. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fruman DA, Cantley LC. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase in immunological systems. Semin. Immunol. 2002;14:7–18. doi: 10.1006/smim.2001.0337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rommel C, Camps M, Ji H. PI3K delta and PI3K gamma: partners in crime in inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis and beyond? Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007;7:191–201. doi: 10.1038/nri2036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vanhaesebroeck B, Vogt PK, Rommel C. PI3K: from the bench to the clinic and back. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2010;347:1–19. doi: 10.1007/82_2010_65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams O, et al. Discovery of dual inhibitors of the immune cell PI3Ks p110delta and p110gamma: a prototype for new anti-inflammatory drugs. Chem. Biol. 2010;17:123–134. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hawkins PT, Stephens LR. PI3K signalling in inflammation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2015;1851:882–897. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barber DF, et al. Class IB-phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) deficiency ameliorates IA-PI3K-induced systemic lupus but not T cell invasion. J. Immunol. 2006;176:589–593. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.1.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barbi J, et al. PI3Kgamma (PI3Kgamma) is essential for efficient induction of CXCR3 on activated T cells. Blood. 2008;112:3048–3051. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-135715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alcazar I, et al. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase gamma participates in T cell receptor-induced T cell activation. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:2977–2987. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Azzi J, et al. The novel therapeutic effect of phosphoinositide 3-kinase-gamma inhibitor AS605240 in autoimmune diabetes. Diabetes. 2012;61:1509–1518. doi: 10.2337/db11-0134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okkenhaug K, et al. Impaired B and T cell antigen receptor signaling in p110delta PI 3-kinase mutant mice. Science. 2002;297:1031–1034. doi: 10.1126/science.1073560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okkenhaug K, et al. The p110delta isoform of phosphoinositide 3-kinase controls clonal expansion and differentiation of Th cells. J. Immunol. 2006;177:5122–5128. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.8.5122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rolf J, et al. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase activity in T cells regulates the magnitude of the germinal center reaction. J. Immunol. 2010;185:4042–4052. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soond DR, et al. PI3K p110delta regulates T-cell cytokine production during primary and secondary immune responses in mice and humans. Blood. 2010;115:2203–2213. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-232330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Macintyre AN, et al. Protein kinase B controls transcriptional programs that direct cytotoxic T cell fate but is dispensable for T cell metabolism. Immunity. 2011;34:224–236. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Han JM, Patterson SJ, Levings MK. The role of the PI3K signaling pathway in CD4(+) T cell differentiation and function. Front Immunol. 2012;3:245. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sauer S, et al. T cell receptor signaling controls Foxp3 expression via PI3K, Akt, and mTOR. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:7797–7802. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800928105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patton DT, et al. Cutting edge: the phosphoinositide 3-kinase p110 delta is critical for the function of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+regulatory T cells. J. Immunol. 2006;177:6598–6602. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.6598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patton DT, Wilson MD, Rowan WC, Soond DR, Okkenhaug K. The PI3K p110delta regulates expression of CD38 on regulatory T cells. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e17359. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Birnbaum LM, et al. Management of chronic allograft nephropathy: a systematic review. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol.: 2009;4:860–865. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05271008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Colvin RB. Chronic allograft nephropathy. N. Eng. J. Med. 2003;349:2288–2290. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp038178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Floess S, et al. Epigenetic control of the foxp3 locus in regulatory T cells. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e38. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim HP, Leonard WJ. CREB/ATF-dependent T cell receptor-induced FoxP3 gene expression: a role for DNA methylation. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:1543–1551. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bartok B, et al. PI3 kinase delta is a key regulator of synoviocyte function in rheumatoid arthritis. Am. J. Pathol. 2012;180:1906–1916. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cornell LD, Smith RN, Colvin RB. Kidney transplantation: mechanisms of rejection and acceptance. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2008;3:189–220. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathmechdis.3.121806.151508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Le Moine A, Goldman M, Abramowicz D. Multiple pathways to allograft rejection. Transplantation. 2002;73:1373–1381. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200205150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Land W. Innate alloimmunity: history and current knowledge. Exp. Clin. Transplant. 2007;5:575–584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen L, et al. TLR engagement prevents transplantation tolerance. Am. J. Transplant. 2006;6:2282–2291. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang T, et al. Prevention of allograft tolerance by bacterial infection with Listeria monocytogenes. J. Immunol. 2008;180:5991–5999. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.5991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu G, Wu Y, Gong S, Zhao Y. Toll-like receptors and graft rejection. Transpl. Immunol. 2006;16:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gorbacheva V, Fan R, Li X, Valujskikh A. Interleukin-17 promotes early allograft inflammation. Am. J. Pathol. 2010;177:1265–1273. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.091106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yuan X, et al. A novel role of CD4 Th17 cells in mediating cardiac allograft rejection and vasculopathy. J. Exp. Med. 2008;205:3133–3144. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ali K, et al. Inactivation of PI(3)K p110delta breaks regulatory T-cell-mediated immune tolerance to cancer. Nature. 2014;510:407–411. doi: 10.1038/nature13444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Polansky JK, et al. DNA methylation controls Foxp3 gene expression. Eur. J. Immunol. 2008;38:1654–1663. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Soond DR, Slack EC, Garden OA, Patton DT, Okkenhaug K. Does the PI3K pathway promote or antagonize regulatory T cell development and function? Front. Immunol. 2012;3:244. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown JR, et al. Idelalisib, an inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase p110delta, for relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2014;123:3390–3397. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-11-535047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hedrick SM, Hess Michelini R, Doedens AL, Goldrath AW, Stone EL. FOXO transcription factors throughout T cell biology. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2012;12:649–661. doi: 10.1038/nri3278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim EH, Suresh M. Role of PI3K/Akt signaling in memory CD8 T cell differentiation. Front. Immunol. 2013;4:20. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Crellin NK, Garcia RV, Levings MK. Altered activation of AKT is required for the suppressive function of human CD4+CD25+T regulatory cells. Blood. 2007;109:2014–2022. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-035279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Finlay DK. Regulation of glucose metabolism in T cells: new insight into the role of Phosphoinositide 3-kinases. Front. Immunol. 2012;3:247. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.King CG, et al. TRAF6 is a T cell-intrinsic negative regulator required for the maintenance of immune homeostasis. Nat. Med. 2006;12:1088–1092. doi: 10.1038/nm1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ben Ahmed M, et al. IL-15 renders conventional lymphocytes resistant to suppressive functions of regulatory T cells through activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway. J. Immunol. 2009;182:6763–6770. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0801792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huynh A, et al. Control of PI(3) kinase in Treg cells maintains homeostasis and lineage stability. Nat. Immunol. 2015;16:188–196. doi: 10.1038/ni.3077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.De Henau O, et al. Overcoming resistance to checkpoint blockade therapy by targeting PI3Kgamma in myeloid cells. Nature. 2016;539:443–447. doi: 10.1038/nature20554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kaneda MM, et al. PI3Kgamma is a molecular switch that controls immune suppression. Nature. 2016;539:437–442. doi: 10.1038/nature19834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wood KJ, Goto R. Mechanisms of rejection: current perspectives. Transplantation. 2012;93:1–10. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31823cab44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Banham-Hall E, Clatworthy MR, Okkenhaug K. The therapeutic potential for PI3K inhibitors in autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Open Rheumatol. J. 2012;6:245–258. doi: 10.2174/1874312901206010245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Barber DF, et al. PI3Kgamma inhibition blocks glomerulonephritis and extends lifespan in a mouse model of systemic lupus. Nat. Med. 2005;11:933–935. doi: 10.1038/nm1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Camps M, et al. Blockade of PI3Kgamma suppresses joint inflammation and damage in mouse models of rheumatoid arthritis. Nat. Med. 2005;11:936–943. doi: 10.1038/nm1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lezama-Davila CM, et al. Role of phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase-gamma (PI3Kgamma)-mediated pathway in 17beta-estradiol-induced killing of L. mexicana in macrophages from C57BL/6 mice. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2008;86:539–543. doi: 10.1038/icb.2008.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Eickholt BJ, et al. Control of axonal growth and regeneration of sensory neurons by the p110delta PI 3-kinase. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e869. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Corry RJ, Winn HJ, Russell PS. Heart transplantation in congenic strains of mice. Transplant. Proc. 1973;5:733–735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Billingham ME, et al. A working formulation for the standardization of nomenclature in the diagnosis of heart and lung rejection: Heart rejection study group. The international society for heart transplantation. J. Heart Transplant. 1990;9:587–593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stewart S, et al. Revision of the 1990 working formulation for the standardization of nomenclature in the diagnosis of heart rejection. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24:1710–1720. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2005.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jurewicz M, et al. Donor antioxidant strategy prolongs cardiac allograft survival by attenuating tissue dendritic cell immunogenicity(dagger) Am. J. Transplant. 2011;11:348–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Winkler DG, et al. PI3K-delta and PI3K-gamma inhibition by IPI-145 abrogates immune responses and suppresses activity in autoimmune and inflammatory disease models. Chem. Biol. 2013;20:1364–1374. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are available from the author on reasonable request.