Abstract

Objective

To evaluate whether stem cell transplantation improves global left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) in patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI), and to determine the appropriate stem cell therapy dose as well as the effective period after stem cell transplantation for therapy.

Methods

A systematic literature search included Pubmed, MEDLINE, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Chinese Biomedical Literature Database (CBM), and Cochrane Evidence-Based Medicine databases. The retrieval time limit ranged from January 1990 to June 2016. We also obtained full texts through manual retrieval, interlibrary loan and document delivery service, or by contacting the authors directly. According to our inclusion and exclusion criteria, data were extracted independently by two evaluators. In case of disagreement, a joint discussion occurred and a third researcher was utilized. Data were analyzed quantitatively using Revman 5.2. Summary results are presented as the weighted mean difference (WMD) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We collected individual trial data and conducted a meta-analysis to compare changes in global left ventricular ejection fraction (ΔLVEF) after stem cell therapy. In this study, four subgroups were based on stem cell dose (≤1 × 107 cells, ≤1 × 108 cells, ≤1 × 109 cells, and ≤1 × 1010 cells) and three subgroups were based on follow-up time (<6 months, 6–12 months, and ≥12 months).

Results

Thirty-four studies, which included 40 randomized controlled trials, were included in this meta-analysis, and 1927 patients were evaluated. Changes in global LVEF were significantly higher in the stem cell transplantation group than in the control group (95% CI: 2.35–4.26%, P < 0.01). We found no significant differences in ΔLVEF between the bone marrow stem cells (BMCs) group and control group when the dose of BMCs was ≤1 × 107 [ΔLVEF 95% CI: 0.12–3.96%, P = 0.04]. The ΔLVEF in the BMCs groups was significantly higher than in the control groups when the dose of BMCs was ≤1 × 108 [ΔLVEF 95% CI: 0.95–4.25%, P = 0.002] and ≤1 × 109 [ΔLVEF 95% CI: 2.31–4.20%, P < 0.01]. In addition, when the dose of BMCs was between 109 and 1010 cells, we did not observe any significant differences [ΔLVEF 95% CI: −0.99–11.82%, P = 0.10]. Our data suggest stem cell therapy improves cardiac function in AMI patients when treated with an appropriate dose of BMCs.

Conclusion

Stem cell transplantation after AMI could improve global LVEF. Stem cells may be effectively administered to patients with AMI doses between 108 and 109 cells.

Keywords: Stem cell, Acute myocardial infarction, Left ventricular ejection fraction, Cell dosage

Introduction

Coronary heart disease is the number one cause of death in China. Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is an important factor that predicts increased mortality and heart failure incidence. Although modern therapeutics such as optimal drug treatment, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), and coronary artery bypass lower patient mortality and improve long-term prognosis, infarcted cells cannot be recovered. As a result, myocardial remodeling ensues and results in heart failure. Therefore, recent studies regarding the treatment of myocardial infarction have focused on how to repair infarcted cells and reduce myocardial remodeling to improve post-infarction heart function.

It has been demonstrated that stem cell transplantation can significantly improve post-AMI systolic and diastolic function, as well as decrease the severity of necrocytosis and apoptosis in animal hearts, thereby resulting in decreased mortality in experimental animals.1 Moreover, clinical studies have found that stem cell transplantation can improve post-infarction left ventricular systolic and diastolic function.2, 3 However, other studies have found that AMI patients did not benefit from stem cell transplantation.4, 5 Therefore, studies are currently evaluating efficacy issues in stem cell transplantation using different types of cells, different routes of transplantation, increased cell doses, and the frequency of transfer.2, 6, 7 Nonetheless, few reports have examined the optimal dose of transferred cells that should be used.8, 9 The present meta-analysis was designed to investigate the impact of various doses of stem cells on the heart function of AMI patients to determine the optimal dose that should be used in patients with AMI.

Materials and methods

Source of data and search strategy

We searched the electronic databases including PubMed, MEDLINE, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Chinese Biomedical Literature Database (CBM), and Cochrane Evidence-based medicine databases using acute myocardial infarction (AMI), stem cell, mononuclear stem cell, and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) as keywords. We evaluated studies published from January 1990 to June 2016. We did not limit the language of the publication. Alternatives included manual retrieval, interlibrary loan, document delivery service, or contacting the author directly.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We employed the following inclusion criteria: (1) Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with follow-up times ≥3 months; (2) Patients clinically diagnosed with AMI. The experimental group received both percutaneous coronary intervention and autologous bone marrow stem cells whereas the control group was prescribed a standard medication regime; (3) Patients in the experimental group received autologous bone marrow stem cells via coronary arteries with no limit to cell types or doses; (4) The outcome variable was left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF); (5) Chinese or English publication language.

Exclusion criteria were the following: (1) Intravenous or intramyocardial injection as the routes of stem cell delivery; (2) Trials with no control group; (3) Incomplete data (or no data) regarding stem cell dose; or (4) Repeated studies on the same subjects.

Data extraction

All references were evaluated by two authors according to the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Data were extracted according to tables designed beforehand and cross-checked. Disagreements were resolved by discussion between the authors and decided by a third investigator, if necessary.

Statistical methods

We used the Revman 5.2 software package (The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark) to perform statistical analyses. Categorical data are presented as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Quantitative data are presented as weighted mean differences (WMD) with 95% CIs. Subgroup analyses were performed according to possible causative factors of clinical heterogeneity, such as various stem cell doses. Heterogeneity was examined using Q tests and I2 statistic. P < 0.1 was regarded as positive heterogeneity. I2 values between 0% and 40% were regarding as unimportant heterogeneity, 30–60% as moderate heterogeneity, 50–90% as significant heterogeneity, and 75–100% as massive heterogeneity. Homogeneous and heterogeneous data were analyzed using the fixed effect and random effect models, respectively.

Results

Literature search results

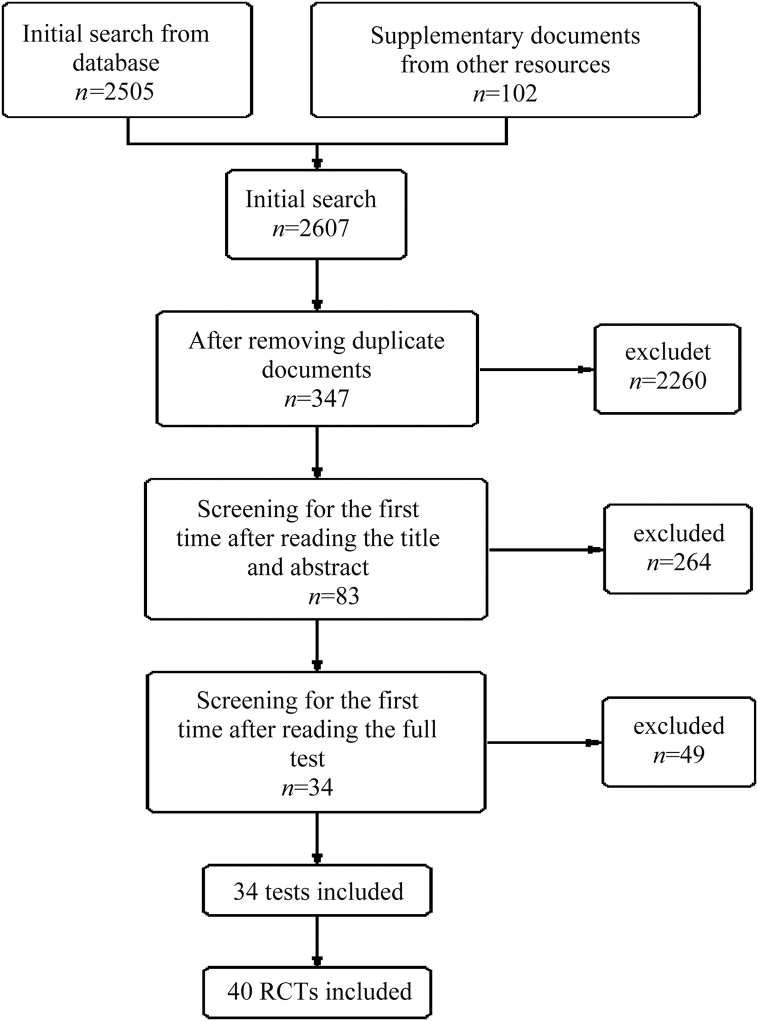

As shown in Fig. 1, 2505 articles were found using computerized methods and an additional 102 were identified by manual retrieval and interlibrary loan. Of the 2607 total articles, 2260 were repetitive and therefore excluded. The titles and abstracts of the remaining 347 articles were read, and another 264 articles were excluded. After reading the complete texts, 49 articles did not meet the inclusion criteria and were excluded. Ultimately, 34 articles containing 40 RCTs were selected.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram to illustrate the data collection and screening processes. RCT: randomized controlled trials.

Material selection

We identified 40 RCTs.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38 Our research variables were differences in LVEF (ΔLVEF) before and after follow-up in both the experimental and control groups. Our meta-analysis included a total of 1927 patients (1037 in the experimental groups and 890 in the control groups). Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

The basic characteristics of included studies.

| Investigator group | Patients (stem cell/control) | Change of LVEF (%) and 95% CI |

Dose of stem cell | Time of stem cell administration, d | Follow-up time, month | Selection of stem cell | Prepare of stem cell administration | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental | Control | |||||||

| Chen (2004) | 34/35 | 18 (4.74) | 6 (5.59) | 8 × 109 | 18.4 | 6 | BMSC | DGS |

| Assmus (2002) | 19/11 | 8.5 (6.44) | 2.5 (6.37) | 7.35 × 106 | 4.3 | 4 | Not given | DGS |

| Manginas (2007) | 12/12 | 2.5 (4.95) | −3.6 (5.59) | 2–16 × 106 | Not given | 13 | BMMC | DGS |

| Hirsch (2010) | 67/60 | 3.8 (7.4) | 4 (5.8) | 2.9 ± 1.6 × 108 | 3–8 | 4 | BMMC | DGS |

| Janssens (2006) | 30/30 | 3.4 (6.9) | 2.2 (7.3) | 1.7 ± 0.7 × 108 | 1 | 4 | BMSC | DGS |

| Kang (2006) | 25/25 | 5.1 (9.1) | −0.2 (8.6) | 1–2 × 109 | 3 | 6 | PBSCs | Spectrum acquisition |

| Meyer (2006) | 30/30 | 6.7 (6.5) | 0.7 (8.1) | 2.4 ± 0.9 × 109 | 4.8 | 6 | BMMC | DGS |

| Quyyumi-HD (2011) | 2/10 | 0.2 (0.8) | 1 (7.8) | 1.4 ± 0.2 × 107 | 8.3 | 6 | BMMC | DGS |

| Quyyumi-LD (2011) | 4/10 | −0.02 (13) | 1 (7.8) | 4.8 ± 0.6 × 106 | 8.3 | 6 | BMMC | DGS |

| Quyyumi-MD (2011) | 5/10 | 6.7 (4) | 1 (7.8) | 9.9 ± 0.7 × 106 | 8.3 | 6 | BMMC | DGS |

| Roman (2015) | 26/24 | 6 (6) | 4 (7) | 6 (3.1–6.5) × 107 | 3–5 | 12 | BMMC | DGS |

| Roncalli (2010) | 47/44 | 1.9 (6.89) | 2.2 (6,87) | 1 × 108 | 9 | 3 | Not given | Unknown |

| Tendera-S (2009) | 51/20 | 4.2 (14.5) | 0.5 (9.08) | 1.9 × 106 | 7 | 6 | BMMC | DGS |

| Tendera-U (2009) | 46/20 | 4.4 (10.92) | 0.5 (9.08) | 1.78 × 108 | 7 | 6 | BMMC | DGS |

| Traverse (2010) | 30/10 | 6.2 (9.8) | 9.4 (10) | 1 × 108 | 3–10 | 6 | BMMC | DGS |

| Wohrle (2010) | 29/13 | 5.7 (8.4) | 1.8 (5.3) | 3.81 ± 1.3 × 108 | 5–7 | 6 | BMMC | DGS |

| Yao-DD (2009) | 15/12 | 7.3 (3.43) | 2.1 (1,71) | 2.0 ± 1.4 × 108 | 3–7 | 3 | BMMC | DGS |

| Yao-SD (2009) | 12/12 | 5.2 (2.72) | 2.1 (1.71) | 1.9 ± 1.2 × 108 | 3–7 | 3 | BMMC | DGS |

| Huang (2006) | 20/20 | 3.3 (2.92) | 1.2 (2.16) | 1.8 ± 4.2 × 108 | 0.08 | 6 | BMMC | DGS |

| Huikun (2008) | 36/36 | 7.1 (12.3) | 1.2 (11.5) | 4.0 ± 2.0 × 108 | 3 | 6 | BMMC | DGS |

| Schachinger (2006) | 27/27 | 3.2 (6.8) | 0.8 (6.8) | 2.4 ± 1.7 × 108 | 3–6 | 4 | BMMC | DGS |

| Suarezdelzo (2007) | 10/10 | 20 (8) | 6 (10) | 9 × 108 | 7 | 3 | BMMC | DGS |

| Sürder LD (2016) | 42/55 | −0.7 (10.11) | −1.9 (9.84) | 1.395 × 108 | 24 | 12 | BMMC | DGS |

| Sürder SD (2016) | 53/55 | −0.9 (10.50) | −1.9 (9.84) | 1.597 × 108 | 6 | 12 | BMMC | DGS |

| Cao (2008) | 41/45 | 8.17 (2.33) | 5.41 (2.43) | 1.25–5.0 × 108 | 7 | 6 | BMMC | DGS |

| Meluzin-HD (2008) | 22/22 | 5 (4.69) | 2 (4.69) | 0.9–2.0 × 108 | 6.8 | 6 | BMMC | DGS |

| Meluzin-LD (2008) | 22/22 | 3 (4.69) | 2 (4.69) | 0.9–2.0 × 107 | 8.9 | 6 | BMMC | DGS |

| Ge (2006) | 10/10 | 4.8 (6.76) | −1.9 (4.14) | 4 × 107 | 0.62 | 6 | BMMC | DGS |

| Huang (2007) | 20/20 | 7.1 (3) | 2.9 (2.6) | 1.2 ± 6.5 × 108 | 1 | 6 | BMMC | DGS |

| Jin (2008) | 14/12 | 4.28 (3.53) | 0.28 (4.03) | 6.3 ± 1.6 × 107 | 7–10 | 6 | BMMC | DGS |

| Karpov (2005) | 16/10 | 6.3 (7.31) | 4.9 (3.85) | 8.8 ± 4.9 × 107 | 7–21 | 6 | BMMC | DGS |

| Li (2007) | 35/23 | 7.1 (5.66) | 1.6 (4.95) | 7.2 ± 7.3 × 107 | 5 | 6 | BMMC | DGS |

| Lunde (2006) | 50/50 | 3.1 (7.9) | 2.1 (9.2) | 0.68 (0.5–1.3) × 108 | 4–8 | 6 | BMMC | DGS |

| Penicka (2007) | 14/10 | 6 (5.41) | 8 (4.03) | 2.64 × 109 | 4–11 | 4 | BMMC | DGS |

| Piepoli (2010) | 17/15 | 12 (5.28) | 6.7 (6.44) | 2.49 × 108 | 4 | 12 | Not given | Unknown |

| Plewka (2009) | 38/18 | 9 (6.1) | 5 (4.95) | 1.44 ± 0.49 × 108 | 7 | 6 | Not given | DGS |

| You (2008) | 7/16 | 13.3 (3.98) | 4 (3.58) | 7.5 × 107 | 14 | 2 | BMSC | DGS |

| Grajek (2010) | 31/14 | 2.74 (7.07) | −0.11 (6.47) | 4.1 ± 1.8 × 108 | 4–6 | 6 | Not given | DGS |

| Nogueira-AG (2009) | 14/6 | 5.5 (7.22) | 0.48 (11.3) | 1 × 108 | 5.5 | 6 | BMMC | DGS |

| Nogueira-VG (2009) | 14/6 | 0.39 (6.39) | 0.48 (11.3) | 1 × 108 | 6 | 6 | BMMC | DGS |

Data of dose of SC and time of SC administration are a separate number, range or mean±SD, depending on original data of the articles.

BMSC: bone marrow stem cell; BMMC: bone marrow mononuclear cell; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG: coronary artery bypass graft; HD: high dose; MD: medium dose; LD: means low dose; S: selected BMSC; U: unselected BMSC; DD: double BMSC dose (first delivery: mean 2.0 (SE 1.4) × 108, second delivery: mean 2.1 (SE 1.7) × 108); SD: single BMSC dose (dose of stem cells: mean 1.9 (SE 1.2) × 108); AG: coronary artery route BMSC; VG: coronary venous route BMSC; DGS: density gradient separation.

Heterogeneity analyses

Heterogeneity was examined using I2 tests. With an overall I2 > 50% in our study, heterogeneity existed among the studies. A random effects model was used for further analyses. In subgroup analyses, the subgroup with a stem cell dose ≤1 × 107 had an I2 value of 0%; therefore, a fixed effect model was used. The heterogeneity in other subgroup analyses (including different doses and follow-up durations) was 0, indicating the population was non-heterogeneous.

Evaluation of ΔLVEF

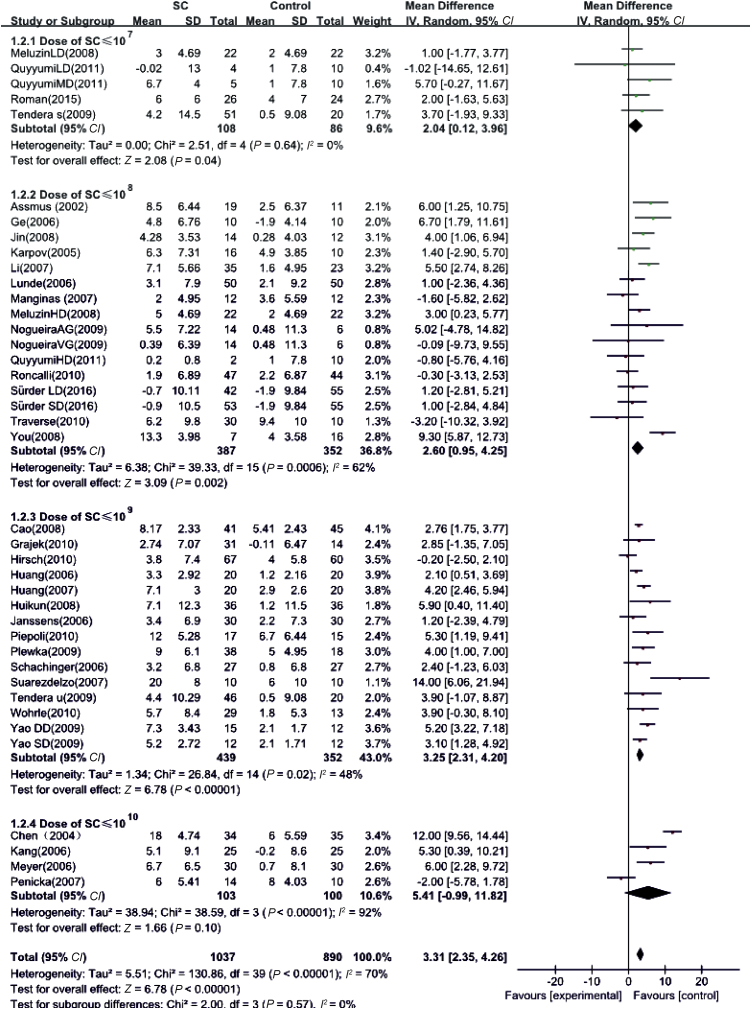

Weighted-mean differences between pre- and post-follow-ups were used as a summary statistic. ΔLVEF in the experimental group was 3.31% (95% CI: 2.35–4.26%, P < 0.01), which was higher than that in control group (Fig. 2). This result suggests that stem cell therapy may enhance the effect on LVEF based on basic treatment in AMI patients.

Fig. 2.

Effects of stem cell dosage on LVEF. SD: standard deviation; SC: stem cell.

The impact of different ΔLVEF doses in AMI patients

Table 2 shows that the 40 RCTs were divided into four groups (stem cell doses ≤1 × 107, ≤1 × 108, ≤1 × 109, and ≤1 × 1010). Analyses of the correlation between stem cell dose and changes in LVEF before and after stem cell transplantation showed that AMI patients who received stem cell therapy had higher ΔLVEF values than control patients. The differences were 2.04% (95% CI: 0.12–3.96%, P = 0.04), 2.60% (95% CI: 0.95–4.25%, P = 0.002), 3.25% (95% CI: 2.31–4.20%, P < 0.01), and 5.41% (95% CI: −0.99–11.82%, P = 0.10), respectively (Fig. 2). Therefore, our data indicate significant LVEF improvement in AMI patients who received stem cell therapy at a dose of 108–109 cells.

Table 2.

Number of patients and studies in groups of different stem cell doses.

| Dose of stem cell | Number of study, n | Number of patients (stem cell/control) |

|---|---|---|

| ≤1 × 107 | 5 | 108/86 |

| ≤1 × 108 | 16 | 387/352 |

| ≤1 × 109 | 15 | 439/352 |

| ≤1 × 1010 | 4 | 103/100 |

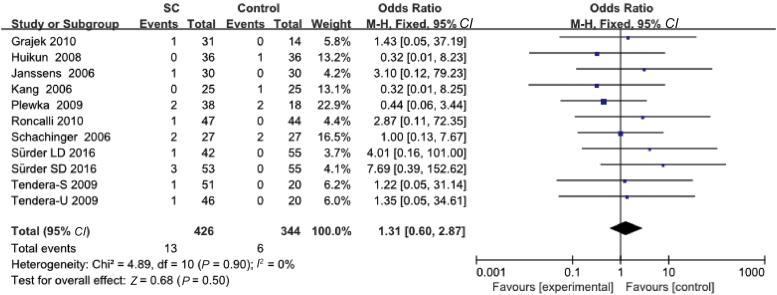

Mortality data

Eleven studies reported deaths cases, in experimental group, there were 13 death cases in total, 6 patients in control group (Table 3). The results showed no significant statistical differences between the experimental group and the control group (95% CI: 0.60–2.87%, P = 0.50) (Fig. 4).

Table 3.

The mortality of included studies.

| Investigator group | Number of patients (stem cell/control) | Number of death (stem cell/control) | Mortality (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental | Control | |||

| Chen (2004) | 34/35 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Assmus (2002) | 19/11 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Manginas (2007) | 12/12 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hirsch (2010) | 67/60 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Janssens (2006) | 30/30 | 1/0 | 3.23 | 0 |

| Kang (2006) | 25/25 | 0/1 | 0 | 0 |

| Meyer (2006) | 30/30 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Quyyumi-HD (2011) | 2/10 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Quyyumi-LD (2011) | 4/10 | 0 | 0 | 2.78 |

| Quyyumi-MD (2011) | 5/10 | 0 | 3.33 | 0 |

| Roman (2015) | 26/24 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Roncalli (2010) | 47/44 | 1/0 | 0 | 4.00 |

| Tendera-S (2009) | 51/20 | 1/0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tendera-U (2009) | 46/20 | 1/0 | 0 | 0 |

| Traverse (2010) | 30/10 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Wohrle (2010) | 29/13 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Yao-DD (2009) | 15/12 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Yao-SD (2009) | 12/12 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Huang (2006) | 20/20 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Huikun (2008) | 36/36 | 0/1 | 0 | 0 |

| Schachinger (2006) | 27/27 | 2/2 | 0 | 0 |

| Suarezdelzo (2007) | 10/10 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sürder LD (2016) | 42/55 | 1/0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sürder SD (2016) | 53/55 | 3/0 | 5.26 | 11.11 |

| Cao (2008) | 41/45 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Meluzin-HD (2008) | 22/22 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Meluzin-LD (2008) | 22/22 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ge (2006) | 10/10 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Huang (2007) | 20/20 | 0 | 2.13 | 0 |

| Jin (2008) | 14/12 | 0 | 7.41 | 7.41 |

| Karpov (2005) | 16/10 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Li (2007) | 35/23 | 0 | 2.38 | 0 |

| Lunde (2006) | 50/50 | 0 | 5.66 | 0 |

| Penicka (2007) | 14/10 | 0 | 1.96 | 0 |

| Piepoli (2010) | 17/15 | 0 | 2.17 | 0 |

| Plewka (2009) | 38/18 | 2/2 | 0 | 0 |

| You (2008) | 7/16 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Grajek (2010) | 31/14 | 1/0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nogueira-AG (2009) | 14/6 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nogueira-VG (2009) | 14/6 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Note: BMSC: bone marrow stem cell; HD: high dose; MD: medium dose; LD: low dose; S: selected BMSC; U: unselected BMSC; DD: double BMSC dose (first delivery: mean 2.0 (SE 1.4) × 108, second delivery: mean 2.1 (SE 1.7) × 108); SD: single BMSC dose (dose of stem cells: mean 1.9 (SE 1.2) × 108); AG: coronary artery route BMSC; VG: coronary venous route BMSC.

Fig. 4.

Mortality of stem cell transplantation.

LD: means low dose; S: selected bone marrow stem cell; U: unselected bone marrow stem cell; SD: single BMSC dose (dose of stem cells: mean 1.9 (SE 1.2) × 108).

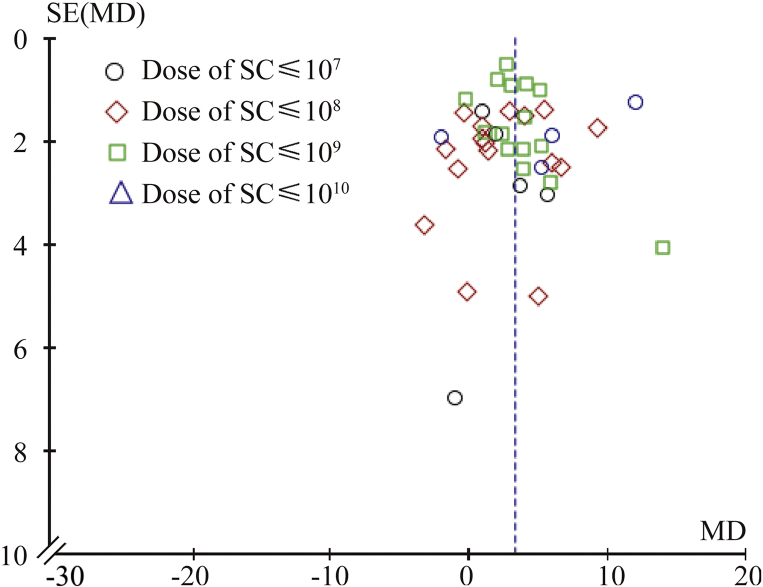

Publication bias evaluation

In our study, we examined publication bias using a funnel plot. We found symmetrical distribution of the included studies, suggesting acceptable publication bias in the studies used in our meta-analysis (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Funnel plot of publication bias. SC: stem cell; MD: medium dose.

Discussion

Our study found improved LVEF in AMI patients after stem cell therapy using a dose of 108–109 cells. Stem cell therapy has been used in the treatment of hematological malignances for more than 40 years.39 Multiple RCTs have assessed its safety and efficacy in heart disease2, 12, 14, 16, 22, 37 and reported that bone morrow-derived stem cell transplantation may improve heart function without increasing the incidence of adverse cardiac events in AMI patients.40 However, compared with the 40% improvement in LVEF in animal experiments,1 there is a lack of large-scale, long-term, multi-center RCT data confirming these results. Indeed, in several clinical studies, LVEF improvement after autologous bone marrow-derived stem cells was minimal and inconsistent. These results are likely attributed to different types of subjects, methods of bone marrow stem cell separation, transplanted stem cell doses, timing of transplantation, and evaluation methods.40, 41 Bone marrow samples were collected under sterile conditions from the iliac crest in local anesthesia. The cell processing in most studies was density gradient centrifugation. Moreover, few studies have evaluated the relationship between cell dose and LVEF. By analyzing the relationship between cell dose and ΔLVEF, we found that as cell dose increases, LVEF improves. In patients that received cell doses ≤1 × 107, although the differences were not significant, there was a trend toward improved LVEF. Of the 40 included studies, 31 involved cell doses between 108 and 109. Results from these studies showed higher ΔLVEF values in the cell transplantation groups compared to control subjects. Using higher cell doses (≤1 × 1010), ΔLVEF was higher in the experimental groups than control groups, although the difference was not statistically significant. If not acquired from in vitro cultivation and amplification, large doses of stem cells indicate a large amount of blood or bone marrow is drawn from AMI patients themselves. Therefore, it is often hard to secure such high doses of stem cells and only four studies (including 103 experimental patients and 100 control patients) using this dose range were included in this meta-analysis. This small sample size may increase sampling error and lead to bias in the final results.42 Other studies have shown that ΔLVEF is 12.00% (95% CI: 9.56–14.44%) higher in the stem cell group.2 However, these results may be related to bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells, which was transplanted in this study. However, the source of stem cells is bone marrow mononuclear cells in other studies.43

Because the majority of studies in this meta-analysis used cell doses of 108–109, we further studied the short- and long-term impact of stem cells in this dose range on the hearts of AMI patients. Most studies lacked long-term consecutive data analyses on patients. Most studies had follow-up periods less than 3 years. Most studies considered short-term (∼6 months) stem cell therapy effective; however, in long-term evaluations, the data are inconsistent regarding whether cell transplantation improved heart function. Currently, few follow-up studies have evaluated patients 18 months to 3 years after cell transplantation. Because it is impossible to objectively evaluate these results, more studies are warranted.

Many factors may have affected our meta-analysis results. First, LVEF is a major variable to evaluate the effect of stem cell therapy, and the methods were not identical. Different methodologies for evaluating heart function may have altered the results. Due to the small sample size, our study was unable to investigate the relationship between different heart function evaluation methods and transplanted cell doses. As more RCTs are published, future meta-analyses can be grouped according to evaluation method and subgroup analyses can be conducted to achieve more reliable results. Moreover, although the majority of included studies showed benefits from stem cell therapy, nine studies suggested no benefits or reported worse outcomes for transplanted patients than controls.4, 5, 10, 15, 27, 30 However, these data may be attributed to the small sample size, which results in large sampling errors and may alter the study results.42

Second, ΔLVEF is not the only variable used to evaluate heart function. Key factors involved in ventricular remodeling and heart dysfunction include myocardial necrosis and the absolute decrease in cardiomyocyte number caused by myocardial ischemia and reperfusion injury. Many studies, in addition to ΔLVEF, also included left ventricular end diastolic volume (LVEDV).17, 18, 25 However, there were insufficient LVEDV data to analyze statistically.

Third, the mortality data and report it either numerically or in table format. Mortality data is absent also important at the moment. Ventricular function is essential, but the change in mortality is crucially more significant parameter, that also reveals any possible adverse effect from cell transplantation. Such data is usually poorly presented in these RCTs. Our study found that the stem cells transplantation had not too much influence on mortality.

Finally, the timing of transplantation may affect the results. Some studies have confirmed that the timing of stem cell introduction affects AMI patients. Immediately after AMI (1–2 days), presumably due to significant myocardial ischemia and inflammation, post-reperfusion oxygen burst, and severe peroxidation injury, there is increased local apoptosis of transplanted stem cells. Thus, the efficacy of stem cell therapy is poor early after AMI. Six to nine days after AMI, debris in the heart is liquefied and absorbed. This process may also influence survival of the surrounding infarct areas and adversely affect transplanted stem cell survival and differentiation. The microenvironment differs in various pathological stages and may affect transplanted stem cell survival and differentiation. In clinical trials, the timing of cell transplantation leads to different results. During chronic and stable stages, the pathological environment differs from the acute state and provides conditions for transplanted stem cell growth and differentiation. Therefore, most studies recommend transplantation 2–9 days after AMI.44 The earliest transplantation noted in our meta-analysis was 2 hours after AMI and the longest transplantation was 24 days after AMI. Therefore, this large time span may affect the results of our study.

Although all included studies were RCTs, the total sample size remained small, thereby resulting in an inevitable bias in summary statistics. Thus, more RCTs that focus on transplanted cell dose are warranted to investigate the optimal stem cell dose for transplantation.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Medical Association.

References

- 1.Orlic D., Kajstura J., Chimenti S. Bone marrow cells regenerate infarcted myocardium. Nature. 2001;410:701–705. doi: 10.1038/35070587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen S.L., Fang W.W., Qian J. Improvement of cardiac function after transplantation of autologous bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Chin Med J. 2004;117:1443–1448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang R.C., Yao K., Qian J.Y. Evaluation of myocardial viability with 201Tl/18F-FDG DISA-SPECT technique in patients with acute myocardial infarction after emergent intracoronary autologous bone marrow mononuclear cells transplantation. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2007;35:500–503. [in Chinese] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Penicka M., Horak J., Kobylka P. Intracoronary injection of autologous bone marrow-derived mononuclear cells in patients with large anterior acute myocardial infarction: a prematurely terminated randomized study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:2373–2374. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Traverse J.H., McKenna D.H., Harvey K. Results of a phase 1, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of bone marrow mononuclear stem cell administration in patients following ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2010;160:428–434. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schächinger V., Assmus B., Britten M.B. Transplantation of progenitor cells and regeneration enhancement in acute myocardial infarction: final one-year results of the TOPCARE-AMI Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:1690–1699. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yerebakan C., Kaminski A., Westphal B. Impact of preoperative left ventricular function and time from infarction on the long-term benefits after intramyocardial CD133(+) bone marrow stem cell transplant. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;142 doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.05.002. 1530–1539.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clifford D.M., Fisher S.A., Brunskill S.J. Stem cell treatment for acute myocardial infarction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2:CD006536. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006536.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin-Rendon E., Brunskill S.J., Hyde C.J., Stanworth S.J., Mathur A., Watt S.M. Autologous bone marrow stem cells to treat acute myocardial infarction: a systematic review. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:1807–1818. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quyyumi A.A., Waller E.K., Murrow J. CD34(+) cell infusion after ST elevation myocardial infarction is associated with improved perfusion and is dose dependent. Am Heart J. 2011;161:98–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cao F., Sun D., Li C. Long-term myocardial functional improvement after autologous bone marrow mononuclear cells transplantation in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: 4 years follow-up. Eur Heart J. 2009 Aug;30(16):1986–1994. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ge J., Li Y., Qian J. Efficacy of emergent transcatheter transplantation of stem cells for treatment of acute myocardial infarction (TCT-STAMI) Heart. 2006;92:1764–1777. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.085431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grajek S., Popiel M., Gil L. Influence of bone marrow stem cells on left ventricle perfusion and ejection fraction in patients with acute myocardial infarction of anterior wall: randomized clinical trial: impact of bone marrow stem cell intracoronary infusion on improvement of microcirculation. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:691–702. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suárez de Lezo J., Herrera C., Pan M. Regenerative therapy in patients with a revascularized acute anterior myocardial infarction and depressed ventricular function. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2007;60:357–365. [in Spanish] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirsch A., Nijveldt R., van der Vleuten P.A. Intracoronary infusion of mononuclear cells from bone marrow or peripheral blood compared with standard therapy in patients after acute myocardial infarction treated by primary percutaneous coronary intervention: results of the randomized controlled HEBE trial. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:1736–1747. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang R.C., Yao K., Zou Y.Z. Long term follow-up on emergent intracoronary autologous bone marrow mononuclear cell transplantation for acute inferior-wall myocardial infarction. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2006;86:1107–1110. [in Chinese] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huikuri H.V., Kervinen K., Niemelä M. Effects of intracoronary injection of mononuclear bone marrow cells on left ventricular function, arrhythmia risk profile, and restenosis after thrombolytic therapy of acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2723–2732. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janssens S., Dubois C., Bogaert J. Autologous bone marrow-derived stem-cell transfer in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;367:113–121. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67861-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yao K., Huang R.C., Ge L. Observation on the safety: clinical trail on intracoronary autologous bone marrow mononuclear cells transplantation for acute myocardial infarction. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2006;34:577–581. [in Chinese] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang H.J., Lee H.Y., Na S.H. Differential effect of intracoronary infusion of mobilized peripheral blood stem cells by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor on left ventricular function and remodeling in patients with acute myocardial infarction versus old myocardial infarction: the MAGIC Cell-3-DES randomized, controlled trial. Circulation. 2006;114(suppl 1):I145–I151. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.001107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karpov R.S., Popov S.V., Markov V.A. Autologous mononuclear bone marrow cells during reparative regeneration after acute myocardial infarction. Bull Exp Biol Med. 2005;140:640–643. doi: 10.1007/s10517-006-0043-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Z.Q., Zhang M., Jing Y.Z. The clinical study of autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation by intracoronary infusion in patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) Int J Cardiol. 2007;115:52–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lunde K., Solheim S., Aakhus S. Intracoronary injection of mononuclear bone marrow cells in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1199–1209. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manginas A., Goussetis E., Koutelou M. Pilot study to evaluate the safety and feasibility of intracoronary CD133(+) and CD133(−) CD34(+) cell therapy in patients with nonviable anterior myocardial infarction. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2007;69:773–781. doi: 10.1002/ccd.21023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meluzín J., Janousek S., Mayer J. Three-, 6-, and 12-month results of autologous transplantation of mononuclear bone marrow cells in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2008;128:185–192. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.04.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyer G.P., Wollert K.C., Lotz J. Intracoronary bone marrow cell transfer after myocardial infarction: eighteen months' follow-up data from the randomized, controlled BOOST (BOne marrOw transfer to enhance ST-elevation infarct regeneration) trial. Circulation. 2006;113:1287–1294. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.575118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nogueira F.B., Silva S.A., Haddad A.F. Systolic function of patients with myocardial infarction undergoing autologous bone marrow transplantation. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2009;93 doi: 10.1590/s0066-782x2009001000010. 374–379, 367–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Piepoli M.F., Vallisa D., Arbasi M. Bone marrow cell transplantation improves cardiac, autonomic, and functional indexes in acute anterior myocardial infarction patients (Cardiac Study) Eur J Heart Fail. 2010;12:172–180. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfp183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Plewka M., Krzemińska-Pakuła M., Lipiec P. Effect of intracoronary injection of mononuclear bone marrow stem cells on left ventricular function in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:1336–1342. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.06.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roncalli J., Mouquet F., Piot C. Intracoronary autologous mononucleated bone marrow cell infusion for acute myocardial infarction: results of the randomized multicenter BONAMI trial. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:1748–1757. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.San Roman J.A., Sánchez P.L., Villa A. Comparison of different bone marrow-derived stem cell approaches in reperfused STEMI. A multicenter, prospective, randomized, open-labeled TECAM trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:2372–2382. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.03.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schächinger V., Erbs S., Elsässer A. Intracoronary bone marrow-derived progenitor cells in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1210–1221. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sürder D., Manka R., Moccetti T. Effect of bone marrow-derived mononuclear cell treatment, early or late after acute myocardial infarction: twelve months CMR and long-term clinical results. Circ Res. 2016;119:481–490. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.308639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.You Q.J., Shen Z.Y., Xiao M.D., Jiang X.C. Influence of autologous bone marrow stem cell transplantation on short-term heart function in cardiac failure patients. Zhongguo Zu Zhi Gong Cheng Yan Jiu Za Zhi. 2008;12:1467–1471. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tendera M., Wojakowski W., Ruzyłło W. Intracoronary infusion of bone marrow-derived selected CD34+CXCR4+ cells and non-selected mononuclear cells in patients with acute STEMI and reduced left ventricular ejection fraction: results of randomized, multicentre Myocardial Regeneration by Intracoronary Infusion of Selected Population of Stem Cells in Acute Myocardial Infarction (REGENT) Trial. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:1313–1321. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wöhrle J., Merkle N., Mailänder V. Results of intracoronary stem cell therapy after acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105:804–812. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.10.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yao K., Huang R., Sun A. Repeated autologous bone marrow mononuclear cell therapy in patients with large myocardial infarction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2009;11:691–698. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfp062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jin B., Yang Y.G., Shi H.M. Autologous intracoronary mononuclear bone marrow cell transplantation for acute anteriormyocardial infarction: outcomes after 12-month follow-up. Zhongguo Zu Zhi Gong Cheng Yan Jiu Za Zhi. 2008;12:2723–2732. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cheuk D.K. Optimal stem cell source for allogeneic stem cell transplantation for hematological malignancies. World J Transpl. 2013;24(3):99–112. doi: 10.5500/wjt.v3.i4.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang S.N., Sun A.J., Ge J.B. Intracoronary autologous bone marrow stem cells transfer for patients with acute myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Int J Cardiol. 2009;136:178–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.04.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Puliafico S.B., Penn M.S., Silver K.H. Stem cell therapy for heart disease. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:1353–1363. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2508-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Whelan K. Editorial: the importance of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of probiotics and prebiotics. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1563–1565. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang S., Ge J., Sun A. Comparison of various kinds of bone marrow stem cells for the repair of infarcted myocardium: single clonally purified non-hematopoietic mesenchymal stem cells serve as a superior source. J Cell Biochem. 2006;99:1132–1147. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang S.X., Xu G.Y., Zhao N.N. Timing-window and therapeutic effects of stem cell transplantation:A Meta-analysis. Zhongguo Zuzhi Gongcheng Za Zhi. 2007;11:2164–2166. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]