Abstract

The rheological standards currently used for classifying refined wheat flour for technological quality of bread are also used for whole wheat flours. The aim of this study was to evaluate the rheological and technological behavior of different whole wheat flours, as well as pre-mixes of refined wheat flour with different replacement levels of wheat bran, to develop a dimensionless number that assigns a numerical scale using results of rheological parameters to solve this problem. Through farinograph and extensograph results, most whole wheat flours evaluated presented parameters recommended for bread making, according to the current classification. However, the specific volume of breads elaborated with these flours was not suitable, that is, the rheological analyses were not able to predict the specific volume of pan bread. The development of the Sehn–Steel dimensionless number allowed establishing a classification of whole wheat flours as “suitable” (Sehn–Steel dimensionless number between 62 and 200) or “unsuitable” for the production of pan bread (Sehn–Steel dimensionless number lower than 62). Moreover, an equation that can predict the specific volume of whole pan bread through this dimensionless number was developed.

Keywords: Whole wheat flour, Farinograph, Extensograph, Whole pan bread, Specific volume

Introduction

Rheological tests on wheat flour can assist the baking industry to predict dough characteristics during processing and final product quality (Schmiele et al. 2012). Within the industry (milling and bakery industries), various devices are used to measure the rheological properties of doughs prepared with wheat flour, and the farinograph, the extensograph and the alveograph are the most commonly used for providing data to evaluate the performance during processing and quality control (Dobraszczyk 1997).

All wheat-based products require flour with specific technological characteristics. The choice of the flour has a strong effect on the ability to formulate an acceptable product (Schmiele et al. 2012). For the baking process, the components of the bran (in particular the fiber, the main biochemical component of the bran) and germ fractions may affect dough rheological properties and, consequently, alter important characteristics of the final product (Khalid et al. 2017). These changes occur because the bran components disrupt the gluten matrix network; thus, reducing its functionality to retain loaf structure during fermentation and baking. The fibers also compete for water with other polymers (proteins and starch), disrupt dough viscoelastic properties and lead to weaker doughs (Rosell et al. 2010; Khalid et al. 2017).

The effects of the addition of these fractions depend on the type of bran (with or without germ, coarse or fine) and on bran replacement levels, which can increase water absorption, reduce dough strength, increase dough viscosity, decreasing mixing and proofing tolerance during processing. Furthermore, they can change the volume, color and sensory characteristics of bread (Zhang and Moore 1997; Hung et al. 2007; Seyer and Gélinas 2009).

A major difficulty found by milling and bakery industries is the correlation of the rheological standards currently used (Mailhot and Patton 1988; Preston and Hoseney 1991; Brasil 2010), which classify refined wheat flours for different applications based on their rheological properties, when using whole wheat flours. The greatest deficiency occurs due to lack of correlation between farinograph and extensograph parameters of whole grain flour and technological characteristics of the final product.

In Brazil, whole wheat flour consists of the reincorporation of bran fractions with or without germ to refined wheat flour, and differs from whole grain wheat flour because it does not necessarily contain the same proportions of the wheat grain. The Brazilian legislation (Brasil 2005) does not establish the minimum proportion of bran and germ required in the refined wheat flour mixture to label a product as originating from whole wheat flour. This is different in other countries, such as Canada, where whole wheat flour must contain the natural constituents of the wheat grain to an extent of at least 95% of the total wheat weight; or in the United States, where whole wheat flour is the product obtained by milling clean wheat, containing the natural constituents of wheat in unchanged proportions (FDR 2017; FDA 1996).

In order to classify whole wheat flours, the development of a dimensionless number that assigns a numerical scale using results of farinograph and extensograph analyses can be a useful tool. Dimensionless numbers are extremely useful to plan and correlate experimental research projects or to interpret the results of experiments. When variables can be identified with some uncertainty, it is possible to group the variables in dimensionless terms expressing certain ratios, by using techniques of dimensional analysis (Vuolo 1996).

The objective of this study was to evaluate the rheological behavior of different whole wheat flours purchased in commercial establishments, and refined wheat flour pre-mixes with different levels of wheat bran replacement (fine and coarse bran), and to develop a dimensionless number capable of classifying whole wheat flours through the specific volume of breads made with these flours.

Materials and methods

Material

Eleven commercial samples of whole wheat flour acquired in commercial establishments were used. For pre-mixes formulation, a refined wheat flour (WF), and two wheat bran samples, fine (FWB), and coarse (CWB), were used, all produced by Moinho Anaconda (BRA). All the samples studied were of the Triticum aestivum species.

Methods

Characterization of raw materials

The raw materials (11 commercial whole wheat flours named as samples 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11, WF, FWB, and CWB) were characterized in triplicate for moisture, protein, fat and ash contents according to methods 44–15.02, 46–13.01, 30–25.00 and 08–01.01 of the AACCI (2010), respectively; total dietary fiber and particle size distribution were determined according to methods 985.29 and 965.22 of the AOAC (2000), respectively.

Rheological characterization of whole wheat flours and pre-mixes

The refined wheat flour was partially replaced by fine bran (samples 12, 13, 14, and 15) and coarse bran (samples 16, 17, 18, and 19) in a proportion of 5, 10, 20, 30% respectively, totaling 8 pre-mixes. The pre-mixes were prepared in a V-blender (TE 200/5, Tecnal, BRA), by mixing portions of 4 kg during 20 min each. The refined wheat flour (WF) was used as control (sample 20).

The commercial whole wheat flours, pre-mixes and refined wheat flour were characterized through farinograph analysis (water absorption, dough development time, stability and mixing tolerance index), according to method 54–21.01 of the AACCI (2010), using a farinograph (827505, Brabender, DEU); and through extensograph analysis (resistance to extension and extensibility), according to method 54–10.01 of the AACCI (2010), in a extensograph (860703, Brabender, DEU). Although some tests using an alveograph were performed, this analysis was not suitable for whole wheat flours, once the excessive resistance caused by the fibers altered the calibration of the equipment.

Manufacture of pan breads

All breads were processed in duplicate using the same formulation, replacing only the flour by commercial whole wheat flour or pre-mix with fine or coarse wheat bran (samples 1–20, as described in the previous sections).

The pan breads were prepared in accordance with Schmiele et al. (2012), with modifications: refined wheat flour, whole wheat flour or pre-mix (100%); sucrose (4%); sodium chloride (1.8%); instant dry yeast (2%); whole milk powder (4%); vegetable shortening (4%); calcium propionate (0.6%) and fungal alpha-amylase (0.0025%) (flour basis). The amount of water was calculated from the water absorption obtained in the farinograph analysis (Table 3).

Table 3.

Rheological properties and dimensionless number of whole wheat flours, pre-mixes and refined wheat flour (C)

| Samples | WA (%) | DDT (min) | S (min) | MTI (BU) | R45 (BU) | R135 (BU) | E45 (mm) | E135 (mm) | SV (mL/g) | Sehn–Steel | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 63.20 | 7.87 ± 0.23i | 7.43 ± 0.12hi | 91.33 ± 7.57ª | 361.67 ± 13.65i | 302.33 ± 56.52f | 92.50 ± 5.41def | 104.83 ± 3.53ab | 3.64 ± 0.05f | 3.051 |

| 2 | 2 | 67.77 | 12.00 ± 0.80bcd | 13.87 ± 1.80cd | 27.33 ± 5.51ghi | 285.67 ± 14.74j | 416.33 ± 53.46def | 96.17 ± 4.16cde | 65.63 ± 2.65gh | 2.37 ± 0.09k | 38.015 |

| 3 | 3 | 61.57 | 10.00 ± 0.61fgh | 12.33 ± 1.26de | 24.67 ± 8.74i | 255.67 ± 17.62j | 511.67 ± 33.98cd | 97.73 ± 6.67bcde | 82.13 ± 3.60cdef | 2.62 ± 0.07j | 92.041 |

| 4 | 4 | 63.17 | 12.13 ± 0.32bcd | 8.30 ± 0.85gh | 41.00 ± 5.29cde | 249.67 ± 14.05j | 372.00 ± 47.00ef | 77.57 ± 2.89ghi | 70.30 ± 4.26fgh | 2.16 ± 0.02l | 11.321 |

| 5 | 5 | 64.57 | 12.00 ± 0.20bcd | 12.00 ± 1.32def | 48.33 ± 2.31c | 406.33 ± 16.56fghi | 575.00 ± 38.57c | 102.20 ± 2.10bcd | 73.13 ± 1.18defgh | 3.40 ± 0.04g | 38.281 |

| 6 | 6 | 66.27 | 11.40 ± 0.53cde | 11.43 ± 0.68def | 29.67 ± 1.15efghi | 489.67 ± 13.01bcd | 589.33 ± 41.65c | 89.73 ± 1.17efg | 71.00 ± 5.33fgh | 3.69 ± 0.03ef | 10.455 |

| 7 | 7 | 66.07 | 11.07 ± 0.61de | 10.30 ± 0.79efg | 39.33 ± 0.58cdef | 375.00 ± 13.75hi | 586.33 ± 76.63c | 95.37 ± 0.38cde | 66.33 ± 5.24gh | 3.38 ± 0.03g | 43.833 |

| 8 | 8 | 62.73 | 8.57 ± 0.60hi | 11.10 ± 0.95ef | 37.00 ± 4.58cdefgh | 300.33 ± 25.54j | 492.33 ± 11.93cde | 93.33 ± 2.83de | 68.90 ± 5.35gh | 2.87 ± 0.06i | 11.109 |

| 9 | 9 | 60.07 | 12.23 ± 1.00bcd | 12.34 ± 0.93de | 36.33 ± 5.77cdefgh | 590.33 ± 20.55ª | 1097.00 ± 56.93ª | 108.67 ± 2.58b | 83.60 ± 5.48cde | 3.80 ± 0.03de | 68.667 |

| 10 | 10 | 66.80 | 13.40 ± 0.56b | 7.43 ± 0.31hi | 38.00 ± 2.65cdefg | 291.67 ± 7.02j | 499.67 ± 38.53cde | 80.80 ± 8.25fgh | 67.77 ± 1.81gh | 2.16 ± 0.06l | 15.121 |

| 11 | 11 | 67.17 | 9.43 ± 0.58gh | 5.80 ± 0.26i | 72.00 ± 2.65b | 409.00 ± 19.70fghi | 538.33 ± 38.81cd | 93.30 ± 3.40de | 71.30 ± 2.46fgh | 3.12 ± 0.07h | 14.668 |

| 12 | 5%FWB | 61.00 | 11.80 ± 0.36cd | 18.40 ± 0.17b | 28.33 ± 3.51fghi | 460.33 ± 21.36cdefg | 788.00 ± 22.34b | 131.67 ± 1.15ª | 107.33 ± 0.58ª | 4.43 ± 0.06ª | 83.675 |

| 13 | 10%FWB | 62.90 | 11.40 ± 0.26cde | 14.81 ± 0.45c | 34.00 ± 1.73defghi | 458.67 ± 24.09cdefg | 755.33 ± 52.73b | 108.67 ± 3.06b | 77.33 ± 4.16defg | 3.89 ± 0.04cd | 81.497 |

| 14 | 20%FWB | 66.90 | 9.37 ± 0.15h | 9.61 ± 0.34fgh | 31.33 ± 3.79defghi | 402.00 ± 18.08ghi | 599.33 ± 36.14c | 96.67 ± 2.89bcde | 72.33 ± 1.53efgh | 3.08 ± 0.04h | 30.790 |

| 15 | 30%FWB | 68.90 | 11.83 ± 0.15cd | 7.22 ± 0.47hi | 38.00 ± 3.61cdefg | 478.00 ± 14.00bcde | 356.67 ± 16.50f | 72.33 ± 4.04hi | 61.67 ± 2.08hi | 2.11 ± 0.03l | 0.662 |

| 16 | 5%CWB | 60.50 | 12.17 ± 0.15bcd | 20.27 ± 0.06b | 28.00 ± 2.65fghi | 462.00 ± 22.72cdef | 803.00 ± 45.31b | 123.33 ± 2.08ª | 94.00 ± 5.57bc | 4.18 ± 0.03b | 113.517 |

| 17 | 10%CWB | 63.00 | 13.37 ± 0.35b | 12.17 ± 0.35de | 26.33 ± 0.58hi | 421.67 ± 21.57efgh | 763.67 ± 51.48b | 107.33 ± 3.06bc | 85.33 ± 7.64cd | 3.96 ± 0.04c | 39.154 |

| 18 | 20%CWB | 67.80 | 10.83 ± 0.45efg | 8.47 ± 0.12gh | 41.33 ± 3.79cd | 432.67 ± 17.67defg | 558.00 ± 7.00c | 88.33 ± 4.16efg | 74.00 ± 1.00defg | 3.01 ± 0.04h | 10.708 |

| 19 | 30%CWB | 68.30 | 12.80 ± 0.10bc | 19.03 ± 0.75b | 13.00 ± 1.00j | 498.33 ± 19.76bc | Nd | 68.00 ± 1.73i | 52.67 ± 4.73i | 2.16 ± 0.03l | 0.000 |

| 20 | WF(C) | 58.20 | 15.33 ± 0.25ª | 23.07 ± 0.76a | 24.67 ± 2.89i | 524.67 ± 34.70b | 997.67 ± 53.20ª | 125.00 ± 7.00a | 93.33 ± 1.53bc | 4.45 ± 0.04ª | 115.271 |

Mean ± standard deviation; FWB fine wheat bran, CWB coarse wheat bran, WF refined wheat flour (control), WA water absorption, DDT dough development time, S stability, MTI mixing tolerance index, R45 resistance after 45 min, R135: resistance after 135 min, E45 extensibility after 45 min, E135: extensibility after 135 min, BU Brabender Units, SV specific volume, Sehn–Steel dimensionless number (calculated according to Eq. 1); Nd not detected; Different lower case letters in the same column indicate significant differences between the samples (p ≤ 0.05)

The ingredients were mixed in a mixer (HAE10, Hypolito, BRA), at low speed (~90 rpm) for 5 min, and at high speed (~210 rpm) until the optimal development of the gluten network. The dough was divided into portions of 450 ± 1 g, which were molded in an molder (MPS 350, GPaniz, BRA), placed in open pans (dimensions 20 cm × 10 cm × 5 cm), and proofed in a proofing chamber (CCKU 5868 20-1, Super Freezer, BRA), at 30 °C, and 80% RH, until the optimum fermentation time.

The breads were baked in an electric oven (IP 4/80, Haas, BRA), adjusted to temperatures of 170 °C (top temperature) and 185 °C (hearth temperature), for 30 min. After baking, the breads were removed from the pans and cooled for 3 h at room temperature. Then, the specific volume (mL/g) was determined in triplicate according to method 10–05.01 of the AACCI (2010).

Statistical analysis

Tukey’s test was used for comparisons of the means of chemical composition, rheological results of flours and bran, and bread specific volume, using Statistica 7.0 software (Statsoft, USA).

The rheological parameters of commercial whole grain flours and pre-mixes, and the specific volume of pan breads were subjected to linear regression analysis (least squares method) for adjustment of linear and quadratic functions, using Statistica 7.0 software (Statsoft, USA).

The development of the Sehn–Steel dimensionless number aimed to organize the whole flour categories to assign a numerical scale using results of rheological variables (farinograph and extensograph) by smoothing parameters, concurrently with the application of the maximum likelihood approach (Vuolo 1996), to determine the exponents of the Sehn–Steel dimensionless function.

According to Vuolo (1996), the maximum likelihood approach adjusts the best function f (x) to a set of experimental points. In the specific case of adjusting a function to a set of data points, the maximum likelihood approach can be adjusted as the best function f (x) to describe a set of data points, which is most likely to be possible if the function f (x) is accepted as a true function. The main tools used to adjust the functions were Statistica and MS-Excel softwares using numerical analysis and linear regression.

Results and discussion

Characterization of raw materials

Table 1 presents the results of the chemical composition of the raw materials. Wheat bran of fine and coarse particle sizes showed higher protein (17.77 and 16.71%), lipids (3.75 and 3.72%), ash (5.54 and 5.94%) and dietary fiber (44.56 and 54.17%) contents than commercial whole wheat flours and refined wheat flour. Wheat bran is obtained from the outer layers of the wheat grain, it mainly consists of pericarp, aleurone, and germ. The protein in these fractions consists of the proteins from bran and germ (albumins and globulins), which have high nutritional value, but low technological quality for baking. The proteins in the endosperm (gliadins and glutenins) were reported to be responsible for dough viscoelastic properties and the formation of the gluten network, a key step in the baking process.

Table 1.

Centesimal composition of whole wheat flour, wheat bran, and refined wheat flour (control)

| Sample | Moisture (%) | Protein (%)* | Lipid (%)* | Ash (%)* | Total Carbohydrates (calculated by difference)* | Total Dietary Fiber (%)*,† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10.63 ± 0.24f | 11.78 ± 0.10de | 1.33 ± 0.19d | 1.11 ± <0.01i | 85.78 | 8.56 ± 0.37gh |

| 2 | 9.58 ± 0.02g | 12.02 ± 0.16d | 1.67 ± 0.06cd | 1.56 ± 0.01def | 84.75 | 13.05 ± 0.48ef |

| 3 | 9.79 ± 0.06g | 11.81 ± 0.23de | 1.36 ± 0.16d | 1.46 ± 0.01efg | 85.37 | 7.62 ± 0.33h |

| 4 | 11.19 ± 0.04de | 11.06 ± 0.28ef | 1.84 ± 0.20cd | 1.82 ± 0.18c | 85.28 | 17.84 ± 2.04c |

| 5 | 11.53 ± 0.13bcd | 10.79 ± 0.39f | 1.82 ± 0.24cd | 1.20 ± 0.01hi | 86.19 | 9.27 ± 0.30gh |

| 6 | 11.57 ± 0.15bc | 11.31 ± 0.05def | 2.64 ± 0.03bc | 1.34 ± 0.02gh | 84.71 | 9.59 ± 0.78gh |

| 7 | 11.65 ± 0.03bc | 11.09 ± 0.09ef | 1.27 ± 0.04d | 1.40 ± 0.03fgh | 85.74 | 11.04 ± 0.65fg |

| 8 | 10.75 ± 0.19f | 13.42 ± 0.29c | 0.97 ± 0.02d | 1.66 ± 0.06cde | 83.95 | 15.15 ± 0.60de |

| 9 | 11.14 ± 0.24e | 9.90 ± 0.05g | 1.70 ± 0.08cd | 1.03 ± 0.23i | 87.37 | 7.99 ± 0.51h |

| 10 | 12.27 ± 0.01ª | 12.99 ± 0.99c | 2.50 ± 1.28c | 1.83 ± 0.11c | 82.68 | 15.50 ± 1.17cd |

| 11 | 11.36 ± 0.01cde | 11.12 ± 0.13ef | 1.62 ± 0.02cd | 1.68 ± 0.31cd | 85.58 | 14.56 ± 0.46de |

| FWB | 11.53 ± 0.10bcd | 17.77 ± 0.12ª | 3.75 ± 0.10ª | 5.54 ± 0.02b | 72.94 | 44.56 ± 0.18b |

| CWB | 11.88 ± 0.11b | 16.71 ± 0.17b | 3.72 ± 0.14ab | 5.94 ± 0.14ª | 73.63 | 54.17 ± 0.25a |

| WF (C) | 11.82 ± 0.43b | 11.07 ± 0.12ef | 1.20 ± 0.10d | 0.57 ± 0.03j | 87.16 | 3.43 ± 0.29i |

Mean ± standard deviation; * Values on a dry basis; † Fraction included in carbohydrates; Different lower case letters in the same column indicate significant differences between the samples (p ≤ 0.05); FWB fine wheat bran, CWB coarse wheat bran, WF refined wheat flour (control)

With respect to the whole wheat flours, samples 4 and 10 showed high fiber (17.84 and 15.50%, respectively) and ash (1.82 and 1.83%, respectively) contents, evidencing that the greater the proportion of bran (and fibers), the higher the ash content, since these minerals are present in higher concentrations in the outer parts of the grain, that is, in the bran. The replacement of 30% WF by fine and coarse bran resulted in samples with 15.77 and 18.65% total dietary fiber, respectively (calculated according to the fiber content of the refined flour and wheat bran), which are similar to the values found in samples 4 and 10. These whole wheat flours acquired in commercial establishments must contain similar percentages (close to 30%) of wheat bran in their composition.

Concerning the particle size (Table 2) of the whole wheat flours and bran, they can be classified as coarse (samples 4, 10, and CWB) and fine (samples 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11 and FWB), according to the classification described by Zhang and Moore (1997), who studied whole flours with different particle sizes. These authors found that the flours with 40% or more particles greater than 0.500 mm (32 mesh) were classified as coarse, while flours containing 60% or more particles smaller than or equal to 0.500 mm (32 mesh) were classified as fine. The particle size influences the water absorption and retention parameters, as well as the dough rheological properties (Al-Saqer et al. 2000). In a study by Wang et al. (2017), fine particles resulted in a shorter dough development time, but greater stability was achieved with smaller particles, which reflected in a stronger gluten network in the dough.

Table 2.

Particle size of whole wheat flour, refined wheat bran, and wheat flour (control) (% retained on the sieves)

| Sample | 12 mesh (1.400 mm) | 20 mesh (0.840 mm) | 32 mesh (0.500 mm) | 60 mesh (0.250 mm) | 80 mesh (0.177 mm) | 100 mesh (0.149 mm) | >100 mesh (>0.149 mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.21 ± 0.10d | 5.74 ± 0.23e | 4.94 ± 0.13j | 22.61 ± 4.80fg | 33.65 ± 1.80a | 13.94 ± 3.15b | 16.99 ± 2.44c |

| 2 | 0.10 ± 0.04h | 0.47 ± 0.07j | 8.29 ± 0.53h | 68.78 ± 0.90a | 18.95 ± 0.40de | 1.48 ± 0.10g | 1.97 ± 0.96g |

| 3 | 0.01 ± 0.01h | 1.83 ± 0.06g | 14.90 ± 0.20f | 53.56 ± 4.30bc | 15.28 ± 0.20f | 6.62 ± 0.50d | 8.07 ± 3.89def |

| 4 | 26.12 ± 0.61a | 17.38 ± 0.70c | 18.59 ± 0.20e | 22.43 ± 0.30f | 5.42 ± 1.32g | 3.91 ± 0.70e | 6.19 ± 1.09ef |

| 5 | 0.77 ± 0.06ef | 2.79 ± 0.14f | 6.34 ± 0.82i | 43.52 ± 9.70cd | 31.34 ± 6.49abc | 6.00 ± 1.60d | 9.30 ± 2.48de |

| 6 | 0.07 ± 0.02h | 1.43 ± 0.10h | 13.47 ± 0.70f | 55.10 ± 1.20b | 22.68 ± 1.70d | 3.25 ± 0.10e | 4.08 ± 0.98f |

| 7 | 1.89 ± 1.04de | 6.82 ± 0.16e | 8.20 ± 0.33h | 39.30 ± 6.00d | 29.05 ± 3.29abc | 6.24 ± 1.10d | 8.55 ± 1.35de |

| 8 | 0.08 ± 0.06h | 0.82 ± 0.09i | 6.58 ± 0.15i | 32.96 ± 1.60de | 16.46 ± 3.45ef | 10.11 ± 1.17c | 33.27 ± 5.79b |

| 9 | 0.54 ± 0.10f | 6.24 ± 0.26e | 9.86 ± 0.31g | 54.40 ± 1.30bc | 25.81 ± 0.41bc | 1.67 ± 0.70fg | 1.57 ± 0.49g |

| 10 | 15.73 ± 0.40b | 24.33 ± 1.00b | 22.47 ± 0.40d | 23.10 ± 0.90f | 5.27 ± 0.64g | 2.53 ± 0.50ef | 6.64 ± 1.38ef |

| 11 | 0.06 ± 0.02h | 2.85 ± 0.10f | 27.89 ± 1.10c | 41.44 ± 2.00d | 14.76 ± 0.26f | 3.20 ± 0.40e | 9.83 ± 0.84d |

| FWB | 0.13 ± 0.03h | 12.60 ± 0.80d | 53.52 ± 0.25a | 31.22 ± 0.50e | 1.07 ± 0.02h | 0.50 ± 0.07h | 0.66 ± 0.03h |

| CWB | 11.30 ± 0.82c | 28.86 ± 0.64a | 36.92 ± 1.06b | 21.19 ± 0.40g | 0.76 ± 0.03i | 0.31 ± 0.07h | 0.38 ± 0.20i |

| WF (C) | 0.26 ± 0.07g | 0.12 ± 0.03k | 0.29 ± 0.15k | 12.54 ± 2.96h | 15.15 ± 3.07ef | 18.56 ± 1.92a | 52.79 ± 7.78a |

Mean ± standard deviation; Different lower case letters in the same column indicate significant differences between the samples (p ≤ 0.05); FWB fine wheat bran, CWB coarse wheat bran, WF refined wheat flour (control)

Rheological analysis of whole grain flour (commercial and pre-mixes) and specific volume of pan breads

Table 3 shows the results of farinograph and extensograph analyses, specific volume of the pan breads made with commercial whole wheat flours, pre-mixes, and refined flour, as well as the Sehn–Steel dimensionless numbers calculated for classification of these samples.

In the farinograph analysis, with respect to the water absorption (WA), the control sample showed a lower value (58.20%), when compared to the whole flour samples (60.07–68.90% for samples 9 and 15, respectively). The high WA value of the whole wheat flours is explained by a greater number of hydroxyl groups in the fiber structure, which allows more associations with water molecules through hydrogen bonding, increase competition for water with other polymers such as proteins and starch, and influence water distribution in the dough (Rosell et al. 2010; Bock et al. 2013).

The highest dough development time (DDT) was found for refined wheat flour (15.33 min). Amongst whole grain flours, samples 10 and 17 had the highest DDT (13.40 and 13.37 min, respectively). For stability (S), refined flour also presented the highest value (23.07 min), followed by whole flours 12, 16 and 19 (18.40, 20.27 and 19.03 min, respectively). The mixing tolerance index (MTI) ranged from 13.00 BU (sample 19) to 91.33 BU (sample 1). However, for this parameter, the low MTI values of some whole wheat flours did not represent better flour quality, but a great interference of the fibers in the consistency of the dough.

According to Kaur et al. (2016), dough strength may be related both to the content and the characteristics of the proteins of wheat flour, in particular of gliadins and glutenins. Among the commercial whole flours analyzed in this work, samples 8 and 10 showed high protein levels (13.42 and 12.99%, respectively), however sample 8 did not present high DDT (8.57 min), and sample 10 did not present high S (7.43 min), indicating that the higher protein content did not reflect in higher dough strength (using these measurements) for whole wheat flours. Earlier, Singh et al. (2016), reported positive correlations were found between the DDT and S parameters and the extractable and unextractable polymeric proteins (which represent the glutenins and were responsible for the elasticity of the dough); and negative correlations were found with the extractable and unextractable monomeric proteins (which represent the gliadins and are responsible for the extensibility of the dough); therefore, glutenin, when present in greater proportions, reflects in greater dough strength. However, in this work, the high S values of some whole flours cannot be attributed only to a higher proportion of glutenin, but to the presence of fibers, which alter the consistency of the dough, causing a false positive result instead of a more stable gluten network.

Regarding the resistance to extension at 45 and 135 min, the highest values were observed for sample 9 (590.33 and 1097.00 BU, respectively), which were higher than sample 20 (refined wheat flour) with values of 524.67 and 997.67 BU at 45 and 135 min, respectively. The lowest values were found for sample 4 (249.67 BU) at 45 min, and sample 1 (302.33 BU) at 135 min. A large variation was also found for the extensibility parameter. The whole samples ranged from 68.00 to 131.67 mm at 45 min and 52.67–107.33 mm at 135 min for samples 19 and 12, respectively. Sample 20 (refined wheat flour) had intermediate values (125 and 93.33 mm) in both periods.

A wide variation between the results was observed for all rheological analyses, evidencing that the components of the whole grain flours, especially the fiber fraction, have a significant effect on these analyses.

The results showed that the vast majority of the whole grain flours analyzed, if current classification parameters were used, would have suitable characteristics for the production of pan breads, as reported by Mailhot and Patton (1988), with medium to high water absorption (60–65%), dough development time from 6 to 8 min, and dough stability of at least 7.5 min. However, when evaluating the specific volumes of the breads made with these flours (Table 3), it was observed that, unlike what happens with the refined wheat flour, these rheological parameters are not able to predict the technological characteristics of pan breads made with the whole wheat flour.

Among the commercial samples, sample 9 showed the highest specific volume (3.80 mL/g), lower fiber content (7.99%), and also high values for DDT and S in the farinograph analysis (12.23 and 12.34 min); and R in the extensograph analysis (590.33 and 1097.00 BU, at 45 and 135 min, respectively), which possibly indicates that the flour in which the wheat bran was reincorporated was strong, suitable for bread making. The same can be observed with samples 12, 13, 16 and 17 (specific volumes of 4.43, 3.89, 4.18, and 3.96 mL/g, respectively), among the samples prepared with substitution of part of the refined wheat flour by wheat bran. The refined wheat flour used in the present study was strong (sample 20), which proves to be an important factor in the production of whole breads with good appearance (high specific volume). In addition, substitutions of up to 10% wheat bran did not cause drastic changes in the specific volume of pan bread, which is the threshold value to obtain pan bread with good specific volume without the use of additives and processing aids.

Samples 4, 10, 15, and 19 had lower specific volumes (2.16, 2.16, 2.11, and 2.16 mL/g, respectively) and higher fiber contents, since samples 15 and 19 were the samples with greater substitutions by wheat bran (30%), confirming that the bran may weaken the gluten network by interactions between proteins and fiber, and dilution of the gluten network, thereby reducing the volume of bread (Gan et al. 1992; Noort et al. 2010). According to Noort et al. (2010), the addition of wheat bran to the dough has a negative effect on the specific volume of breads. These authors have shown that the fiber interacted physically and chemically with gluten-forming proteins, hampering protein aggregation, resulting in reduced stability of the gas cells. Furthermore, according to them, the dilution effect of the gluten network caused by fiber incorporation may be a secondary effect responsible for the decrease in bread volume.

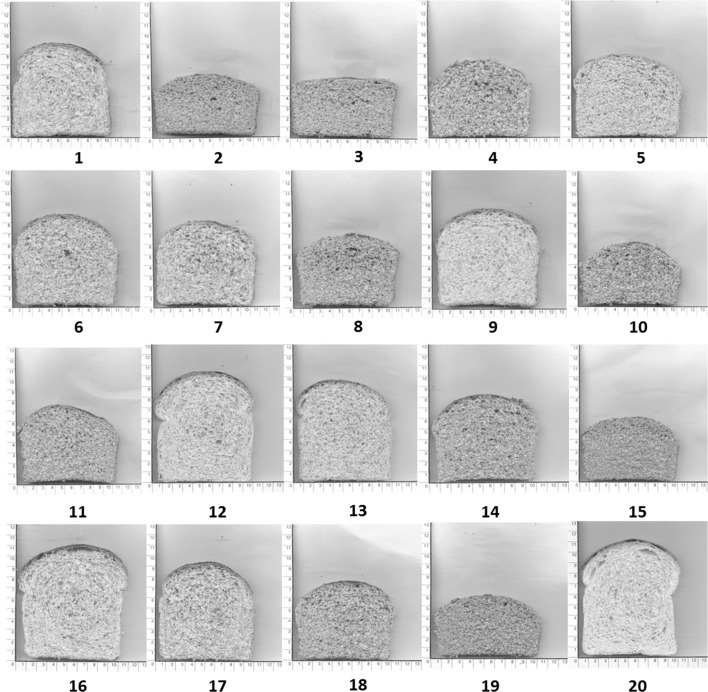

As reported by Zhang and Moore (1997), the particle size of wheat bran has a significant effect on the specific volume and sensory quality of bread, where finer particles tend to result in lower specific volumes, while coarser particles lead to a lower acceptance of the bread. In contrast, Wang et al. (2017) suggest, in their study, that smaller particles can improve the quality of whole wheat breads by strengthening the gluten network in the dough, resulting in bread with higher specific volume and better crumb grain structure. In this study, flours of both particle sizes, fine and coarse, had low specific volumes when associated with high fiber contents; however, the effect was greater when coarse particles were used. Figure 1 shows images of the central slices of the whole pan breads.

Fig. 1.

Central slices of breads made with commercial whole wheat flours (1–11), with replacement of 5, 10, 20 and 30% refined wheat flour by fine bran (12 and 15, respectively) and coarse bran (16–19, respectively), and refined wheat flour (20)

Ishida and Steel (2014) studied different commercial whole pan breads and found the lowest specific volume was 3.88 mL/g. This value was used as the specific volume reference for the selection of suitable or unsuitable whole wheat flours for bread making. Suitable whole wheat flours for bread making can produce breads with a specific volume equal to or greater than 3.8 mL/g using the formulation described in the Materials and methods section, without the use of additives and processing aids. On the other hand, unsuitable whole wheat flours produce whole breads with a lower specific volume (<3.8 mL/g). For the unsuitable whole flours, a more detailed study using different additives and processing aids (enzymes) is required for application in the production of whole pan breads.

Sehn–Steel dimensionless number

The variables of the farinograph analysis used for determining the Sehn–Steel dimensionless number were water absorption, dough development time, dough stability, and mixing tolerance index, while the extensograph variables were resistance to extension and extensibility at 45 and 135 min. The intermediate time of 90 min was not used, since the difference between the maximum and minimum values of the dimensionless number calculated using the times of 135 and 45 min was greater than the difference using the maximum and minimum values at 90 and 45 min.

The development of the Sehn–Steel dimensionless number involved calculations to select the rheological results of the whole grain flour by smoothing parameters, concurrently with the application of the maximum likelihood approach to determine the exponents, as described in Eq. 1.

| 1 |

where WA, water absorption of the flour (g/100 g); 14, medium water content in wheat flour (14 g/100 g); S, dough stability (minutes); DDT, dough development time (minutes); 500, resistance of the dough to extension, expressed in arbitrary units (BU); MTI, mixing tolerance index (BU); E45, dough extensibility at 45 min (mm); E135, dough extensibility at 135 min (mm); R45, resistance to extension or elasticity of the dough at 45 min (BU); R135, resistance to extension or elasticity of the dough at 135 min (BU).

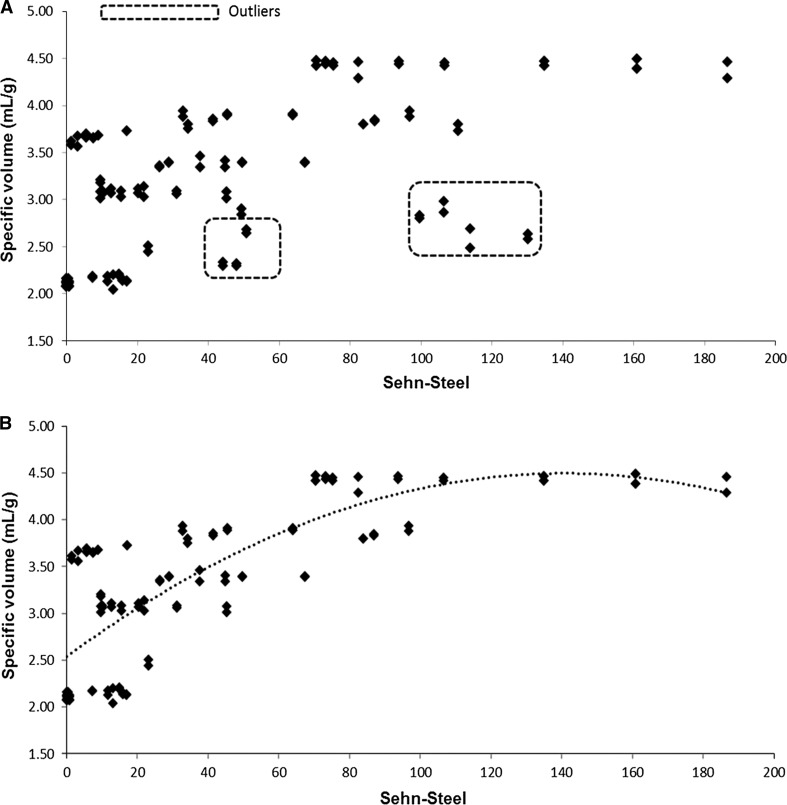

Table 3 shows the Sehn–Steel dimensionless numbers for all samples of this study, calculated according to Eq. 1. Figure 2 shows the results of the specific volume as a function of the Sehn–Steel dimensionless number. Some results were considered outliers in the statistical data. These results were excluded from this set of points, and the set of remaining points showed the geometric formation of a parabola with the maximum Sehn–Steel dimensionless number of 140–160 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Specific volumes of pan breads made with commercial whole wheat flour and pre-mixes of refined wheat flour and wheat bran as a function of the Sehn–Steel dimensionless number (a) and excluding the outliers (b)

After the removal of the outliers, the sample with replacement of 10% bran (F17) had results outside the classification, probably as the classification is artificial and uses a stochastic model. The removal of these outliers did not cause impairment to the classification.

The classification of whole grain flours using the Sehn–Steel dimensionless number is proposed according to Eq. 1. Two classes were established using the specific volume as technological quality parameter (Table 4). Thus, the flours that yield pan breads with specific volumes below 3.8 mL/g, and have Sehn–Steel dimensionless numbers between 0 and 62 were considered “unsuitable” flours, while flours that yield pan breads with specific volumes of 3.8 mL/g or higher, and have Sehn–Steel dimensionless numbers between 62 and 200 were considered “suitable” for bread making.

Table 4.

Classification of whole grain flour for the production of pan bread

| Sehn–Steel | Whole wheat flour | SV (mL/g) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 ≤ Sehn < 62 | Unsuitable | Less than 3.8 |

| 62 ≤ Sehn ≤ 200 | Suitable | Approximately or more than 3.8 |

SV specific volume, Sehn–Steel: dimensionless number (calculated according to Eq. 1)

Analysis of variance of the quadratic adjustment and statistical model of the specific volume as a function of the Sehn–Steel dimensionless number

For the analysis of variance of the relationship between the specific volume and the Sehn–Steel dimensionless number, the probability of significance found was of 0.00000 (p ≤ 0.05), confirming that the linear regression model was statistically significant. The proportion of explained variance (R2) found was of 0.64.

A statistical model was created to predict the specific volume of pan breads made with whole wheat flour (Eq. 2), using the Sehn–Steel dimensionless number.

| 2 |

where SV, specific volume; Sehn–Steel, dimensionless number calculated according to Eq. 1; e, experimental error.

This equation uses the Sehn–Steel dimensionless number (as an independent variable to describe the behavior of the specific volume of pan breads with whole wheat flours) and can be applied to different particle sizes, without the need for a distinction or previous particle size analysis. The Sehn–Steel dimensionless number is calculated using the results of rheological analysis (farinograph and extensograph), thus it is possible to determine it and predict the specific volume of pan breads made with whole wheat flour.

Conclusion

This study developed the Sehn–Steel dimensionless number, which allows establishing a classification of whole wheat flours indicating its suitability for the production of pan breads, using as a criterion the specific volume. Thus, whole flours with a Sehn–Steel dimensionless number lower than 62 may be considered “unsuitable”, while whole flours with number between 62 and 200 may be considered “suitable” for bread making. Also, an equation that predicts the specific volume of breads made with whole wheat flour using the Sehn–Steel dimensionless number was developed. This classification can be used to predict the technological quality of whole wheat flour thus helping mills and bakery industries to select the most suitable flours for pan bread making.

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) and São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) (Project 2013/08538-0) for financial support, and the Milling Industries Santa Catarina, Anaconda, Paulista, LCA Alimentos, Antoniazzi and Correcta for the donation of the raw materials.

Contributor Information

Georgia Ane Raquel Sehn, Email: georgia.sehn@gmail.com.

Caroline Joy Steel, Phone: +55 19 3521 3999, Email: steel@unicamp.br.

References

- AACCI American Association of Cereal Chemists International . Approved methods. 11. St. Paul: American Association of Cereal Chemistry International; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Saqer J, Sidhu J, Al-Hooti S. Instrumental texture and baking quality of high-fiber toast bread as affected by added wheat mill fractions. J Food Process Preserv. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- AOAC Association of Official Analytical Chemists . Official methods of analysis of Association of Official Analytical Chemists. 17. Gaithersburg: Association of Official Analytical Chemists; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bock JE, Connelly RK, Damodaran S. Impact of bran addition on water properties and gluten secondary structure in wheat flour doughs studied by attenuated total reflectance fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Cereal Chem. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Brasil Ministério da Agricultura, Pecuária e Abastecimento (2005) Instrução Normativa nº8 Regulamento Técnico de Identidade e Qualidade da Farinha de trigo. http://sistemasweb.agricultura.gov.br/sislegis/action/detalhaAto.do?method=visualizarAtoPortalMapa&chave=803790937. Accessed 18 July 2016

- Brasil Ministério da Agricultura, Pecuária e Abastecimento Instrução Normativa nº38, de 30 de novembro de 2010 Regulamento Técnico do trigo. http://sistemasweb.agricultura.gov.br/sislegis/action/detalhaAto.do?method=visualizarAtoPortalMapa&chave=358389789. Accessed 18 July 2016

- Dobraszczyk BJ. The rheological basis of dough stickiness. J Texture Stud. 1997 [Google Scholar]

- FDA Food and Drugs Administration (1996) 21 CFR 102.5-General Principles. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CFR-1996-title21-vol2/pdf/CFR-1996-title21-vol2-sec137-200.pdf. Accessed 18 June 2017

- FDR Food and Drug Regulations (2017) C.R.C., c. 870. Division 13—Grain and bakery Products. http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/PDF/C.R.C.,_c._870.pdf. Accessed 18 June 2017

- Gan Z, Galliard T, Ellis PR, Angold RE, Vaughan JG. Effect of the outer bran layers on the loaf volume of wheat bread. J Cereal Sci. 1992 [Google Scholar]

- Hung PV, Maeda T, Morita N. Dough and bread qualities of flours with whole waxy wheat flour substitution. Food Res Int. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- Ishida PMG, Steel CJ. Physicochemical and sensory characteristics of pan bread samples available in the Brazilian market. Food Sci Technol. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- Kaur A, Shevkani K, Katyal M, Singh N, Ahlawat AK, Singh AM. Physicochemical and rheological properties of starch and flour from different durum wheat varieties and their relationships with noodle quality. J Food Sci Technol. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s13197-016-2202-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalid KH, Ohm JB, Simsek S. Whole wheat bread: effect of bran fractions on dough and endproduct quality. J Cereal Sci. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- Mailhot WC, Patton JC. Criteria of flour quality. In: Pomeranz Y, editor. Wheat: Chemistry and Technology. St. Paul: American Association of Cereal Chemists; 1988. pp. 69–90. [Google Scholar]

- Noort MWJ, van Haaster D, Hemery Y, Schols HA, Hamer RJ. The effect of particle size of wheat bran fractions on bread quality—evidence for fiber–protein interactions. J Cereal Sci. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Preston KR, Hoseney RC. Applications of the extensograph. In: Rasper F, Preston KR, editors. The extensograph handbook. St. Paul: American Association of Cereal Chemistry; 1991. pp. 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Rosell CM, Santos E, Collar C. Physical characterization of fiber-enriched bread doughs by dual mixing and temperature constraint using the Mixolab®. Eur Food Res Technol. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Schmiele M, Jaekel LZ, Patricio SMC, Steel CJ, Chang YK. Rheological properties of wheat flour and quality characteristics of pan bread as modified by partial additions of wheat bran or whole grain wheat flour. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Seyer MÈ, Gélinas P. Bran characteristics and wheat performance in whole wheat bread. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Singh N, Kaur A, Katyal M, Bhinder S, Ahlawat AK, Singh AM. Diversity in quality traits amongst Indian wheat varieties II: paste, dough and muffin making properties. Food Chem. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuolo JH. Fundamentos da teoria de erros. 2. São Paulo: Edgard Blücher Ltda; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Wang N, Hou GG, Dubat A. Effects of flour particle size on the quality attributes of reconstituted whole-wheat flour and Chinese southern-type steamed bread. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2017;82:147–153. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2017.04.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Moore WR. Effect of wheat bran particle size on dough rheological properties. J Sci Food Agric. 1997 [Google Scholar]