Abstract

Rice vermicelli is a main food consumed in China and Southeast Asia. Quality of rice vermicelli varies with rice cultivars. Parameters including amylose content, amylopectin distribution, thermal and pasting characteristics, gel texture and starch granules of three rice cultivars “Zhongjiazao 17”, “Xiangzaoxian 24” and “Thai Jasmine Rice”, were studied for their impacts on vermicelli quality. Results showed significant differences for the measurements of the quality traits and indicated that a favorable quality of vermicelli was not determined by any single factor instead of a combination of multi-parameters. A vermicelli with a favorable quality could be produced from a rice variety with a high apparent amylose content (>25%), a protein content of 11%, an intermediate gelatinization temperature and gel consistency, and a gel hardness (~3 N for a Rapid Viscosity Analyzer pasting) and moderate retrogradation capacity (a setback viscosity of 30–100 RVU).

Keywords: Amylose content, Amylopectin distribution, Gel texture, Thermal properties, Sensory evaluation

Introduction

Rice is a staple food in Asia. Rice is grown in China as for three cropping seasons, i.e. early, middle and late seasons. About 16% of the 200 Mt annual rice production in China is grown as early season indica type, which has a comparatively poor cooking and eating quality than the grains harvested from other two seasons. One usage of early season indica rice is to produce vermicelli which is a highly prized food in southern and southeastern parts of China and across Southeast Asia (Hormdok and Noomhorm 2007). Rice vermicelli is made by extruding wet-milled and gelatinized rice dough. Quality of rice vermicelli is highly dependent on a cultivar’s quality. In general, rice vermicelli is manufactured by using a long grain rice containing >22% of amylose (Kohlwey et al. 1995). Li and Luh (1980) reported that rice vermicelli requires a rice flour with a high apparent amylose content (AAC), a low gelatinization temperature (GT) and a hard gel consistency (GC) (Li and Luh 1980). Gel hardness is also used to predict vermicelli quality from flour (Yoenyongbuddhagal and Noomhorm 2002). Ding et al. (2004) show that rice flour for vermicelli should have characteristics of AAC between 23 and 28%, GC between 30 and 45 mm and swelling power (SP) between 8.0 and 9.0. Hormdok and Noomhorm (2007) suggested that the Rapid Viscosity Analyzer (RVA), which measures paste properties, can provide a predictive value for suitability of rice flour being used for quality vermicelli, while Han et al. (2011) maintain that paste properties, % damaged starch and a high AAC can be used for this purpose (NY/T 2639-2014). A rice variety, “Zhongjiazao17” (Z17), has been popularly growing in south China as early season crop with high yielding, tolerant to stress and diseases. From 2009 being approved for commercial production up to 2015, the variety has been cumulatively planted for over 682,000 ha, making it as one of just two indica cultivars over the past 30 years with a planting area greater than 667,000 ha. The cultivar has also been well received by vermicelli manufacturers in China for producing rice vermicelli. The flour of Z17 has an intermediate peak viscosity and an AAC of 25.9%. Another cultivar, “Xiangzaoxian24” (X24) shares a similar AAC and protein content (PC) with Z17, but produces inferior quality of vermicelli. A Thai Jasmine Rice (TJR), brand name as “Golden Chiangrai”, has a low AAC (15.0%) and a similar peak viscosity as that of X24. TJR is a rice variety with a premium quality for cooked rice, but the vermicelli quality made from it is even worse than that of X24. The objective of the study was to explore physicochemical properties of AAC, PC, GT and GC and other quality traits for providing a predictive value of producing a high quality of rice vermicelli.

Materials and methods

Rice samples

Z17 and X24 grain were obtained from the China National Rice Research Institute, while TJR grain was purchased from a rice market and branded as imported from Thailand. Each grain sample of paddy rice was weighted for 140 g and air-dried to a moisture content of ~12%. The samples were de-hulled using a testing husker (Model THU-35A, Satake Engineering Co. Ltd., Hiroshima, Japan) and milled using a McGill Miller No. 2 (Seedburo Equipment Co., Chicago, IL, USA). Each sample was milled (Cyclotec 1093, Foss Tecator AB, Höganäs, Sweden) for flour which was fine enough to pass through a 0.42 mm screen.

Analysis of physico-chemical properties of the flour

The AAC of the flours was determined using the Chinese Ministry of Agriculture’s NY/T 2639-2014 method. PC was obtained by the Kjeldahl method using a Kjell-Foss 16200 Auto-analyzer (AOAC 1999). Assessment of GC and GT followed the NY/T 147-1988 method issued by the Chinese Ministry of Agriculture. SP and solubility analyses followed Hormdok and Noomhorm (2007). Thermal properties of milled rice flour were analyzed using a DSC 1 differential scanning calorimeter (Mettler Toledo, Greifensee, Switzerland). A sample of 5 mg rice flour was placed in an aluminum pan with 10 μL distilled water, then the pan was sealed and heated at 10 °C/min from 30 to 95 °C. A sealed empty pan was used as for a reference. The values of onset (To), peak (TP), conclusion (Tc) and gelatinization enthalpy (ΔH) were calculated automatically by the onboard STARe software. For the evaluation of retrogradation, the pans were held 4 °C for 10 days and then subjected to the same heating profile.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

Morphologic characteristics of granules were examined by a scanning electron microscopy (SEM S-4300; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). Dehydrated samples were attached to a copper stub using double-sided adhesive tape, and were then coated with gold using a vacuum evaporator. A magnification of 5000× was applied for observing starch granules.

Pasting properties and gel texture

The pasting properties of rice flours were analyzed in triplicate using a Rapid Viscosity Analyzer (RVA model 4, Newport Scientific Pty. Ltd., Warriewood, NSW, Australia) following Xie et al. (2015). A formula (2, 7, 1, 10) was expressed as the pasting temperature (PT) at a 10 RVU viscosity change rate between t1 (2 min) and t2 (7 min) of curves (Xie et al. 2015). To characterize gelatinization, the same material in the pan was held for 20 h at 4 °C following the RVA analysis with paddle removed and dough flattened. The container was then sealed with parafilm to prevent moisture loss. Gel texture was determined using a TMS-Pro texture analyzer (Food Technology Corporation, Sterling, VA, USA). The gel was compressed by a flat-faced cylinder probe until it reached a deformation of 40% at a speed of 30.0 mm/s. There was no hold time between the first and the second cycles, which were run using a 25 N cell load. The fracture, first hardness (hardness 1), adhesiveness force, adhesiveness and the second hardness (hardness 2) were obtained from the force–time curve.

Determination of amylose content using gel permeation chromatography/size-exclusion chromatography (GPC/SEC)

A 50 mg sample of rice flour was dispersed into 2 mL 0.25 M NaOH and held at 40 °C for 3 h. An 800 µL of gelatinized solution was transferred into a fresh 2 mL microfuge tube with 0.2 mol/L 200 µL Na acetate buffer (pH 4.0) added, along with 20 µL 1000 U/mL Pseudomonas isoamylase (Megazyme, Wicklow, Ireland). The reaction was held at 50 °C for 2 h, then centrifuged (5600×g, 10.0 min), and boiled for 5 min to denature the isoamylase. The digest was subsequently subjected to GPC/SEC using a PL-GPC 120 device (Polymer Laboratories Ltd., Church Stretton, and UK). A 7.8 mm × 300 mm Ultrahydrogel™ 250 column (Waters, Milford, MA, USA), a guard column (Phenomenex Inc., Lane Cove, NSW, Australia) and the detector were all maintained at 37 °C. The injection temperature was 40 °C. Ammonium acetate (0.05 M, pH 4.75) was used as the eluent at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min.

Amylopectin chain length distribution

The distribution of amylopectin chain length was obtained following O’Shea et al. (1998) based on the use of a Beckman Coulter P/ACE 5510 capillary electrophoresis system (www.beckmancoulter.com) with an argon laser-induced fluorescence (LIF) detector.

Preparation of wet vermicelli

Milled flour passing through a 0.42 mm screen was mixed with seven parts of water. Dough was thoroughly mixed, flattened and then steamed for 20 min to complete the process of gelatinization, subsequently extruded using a cylindrical hand extruder equipped with a 1.6 mm diameter aperture. The resulting vermicelli were cooked in boiling water for 10 s, and cooled by addition of excess cold water (4 °C), and then stored at −10 °C for 10 h.

Quality evaluation of wet vermicelli

The water content of the vermicelli was measured by weight loss after drying at 105 °C for 4 h. The absorbance of the iodine–starch complex at 620 nm (iodine blue value, BV) and broken ratio value (BR) were determined following Luo et al. (2011).

Sensory evaluation

A 200 g sample of freshly made vermicelli was boiled for 3 min in 0.5 L water. The cooked samples were evaluated by a panel of three trained males (ages as twenties, thirties and forties) and four females (ages as twenties, thirties, forties and fifties). Samples were scored for color, odor, appearance, flavor and texture (Table 1). Each entry was received a cooking and eating quality score based on the mean assessment of the seven panelists.

Table 1.

Sensory evaluation of wet vermicelli produced from the flour of three rice cultivars

| Parameter | Description | Scores |

|---|---|---|

| Color | Uniformity color, white/original color; transparent | 8–10 |

| Whiteness/original color with few color variegation, transparent | 5–7 | |

| No-uniformity color, non-transparent | 0–4 | |

| Odor | Aromatic or obviously pure smell | 8–10 |

| Pure smell or with few unpleasant smell | 5–7 | |

| Non-pure with unpleasant smell | 0–4 | |

| Appearance | Glossy, intact without piece | 8–10 |

| Glossy, intact with few piece | 5–7 | |

| Non-glossy, non-intact with more pieces | 0–4 | |

| Flavor and texture | Good springiness and chewiness, appropriate hardness and cohesiveness | 8–10 |

| Moderate springiness and chewiness, medium harness and cohesiveness | 5–7 | |

| Low springiness and chewiness, high hardness and cohesiveness | 0–4 |

Springiness Degree grains return to original shape after partial compression

Cohesiveness Degree to which the grains deform rather than crumble, crack, or break when biting with molars

Chewiness Amount of work to chew the sample

Hardness Force required to bite through the sample with the molars

Statistical analysis

Analyses of variance analysis was performed using the Duncan multiple-range test as in a SAS v8.0 software package (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results and discussion

Quality and sensory evaluation

The vermicelli produced from TJR had a significantly higher water content (75.23%) than those of Z17 (72.45%) and X24 (72.30%). With respect to the iodine BVs, Z17 vermicelli (0.156) scored significantly higher than X24 (0.028) and TJR (0.034). The BR values of vermicelli varied significantly (p < 0.01), with Z17 vermicelli scoring the lowest (8.2%) as compared with X24 (10.6%) and TJR (32.5%). Sensory evaluation showed that the three varieties had a similar performance of color odor, but the appearance of TJR was scored lower than the other two varieties. Out of a maximum score of 40 in sensory evaluation, the Z17 vermicelli was scored as for 35.5, against 31.3 of X24 and 29.1 of TJR respectively. Flavor and Texture of Z17 vermicelli were the main advantage traits for a high sensory evaluation compared to other two variety vermicelli.

AAC, PC, GT and GC values

As shown in Table 2, the AAC of the three flour were 25.9, 25.3 and 14.9% for Z17, X24 and TJR respectively. Protein content of the three varieties varied from 7.7% for TJR, 11% for X24 and 12.1% for Z17 respectively; Z17 and X24 showed a similar GT (5.3 for Z17 and 5.5 for X24), but their GC performed different significantly as Z17 was showed as intermediate (52 mm) and X24 showed as low (38 mm). Scores of GT and GC of TJR was the highest among the three samples. Considering the trait variations of AAC, PC, GT and GC of the three varieties, it was difficult to draw a conclusion that any single flour trait could be used for determining vermicelli quality.

Table 2.

The physiochemical properties of the three cultivars’ flour and the vermicelli produced from them

| Parameters | Variety | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Z17 | X24 | TJR | |

| AAC% | 25.9 ± 0.3aA | 25.3 ± 0.4aA | 14.9 ± 0.3bB |

| PC% | 12.1 ± 0.2aA | 11.0 ± 0.1bA | 7.7 ± 0.1cB |

| GT (grade) | 5.3 ± 0.10bB | 5.5 ± 0.2bB | 7.0 ± 0.0aA |

| GC (mm) | 52.0 ± 2.0bB | 38.0 ± 3.0cC | 87.0 ± 1.5aA |

| SP | 12.63 ± 0.19bA | 11.28 ± 0.11cB | 13.55 ± 0.14aA |

| Solubility | 11.35 ± 0.15bBA | 10.23 ± 0.16cC | 13.28 ± 0.16aA |

| AC% | 19.8 ± 0.5bB | 21.1 ± 0.6aA | 8.8 ± 0.2cC |

| Long amylopectin chain% | 18.4 ± 0.3aA | 18.5 ± 0.3aA | 18.4 ± 0.2aA |

| Short amylopectin chain% | 61.8 ± 0.3bB | 60.4 ± 0.5cC | 72.7 ± 0.6aA |

| Amylopectin distribution% | |||

| DP 2–5 | ND | ND | 0.6 ± 0.02aA |

| DP 6–10 | 22.5 ± 0.5bB | 19.2 ± 0.3cC | 24.2 ± 0.5aA |

| DP 11–20 | 67.9 ± 0.6bB | 69.9 ± 0.4aA | 66.2 ± 0.2cC |

| DP > 21 | 9.9 ± 0.3bB | 10.9 ± 0.2aA | 9.0 ± 0.2cC |

| DSC | |||

| To | 72.31 ± 0.23bB | 75.73 ± 0.17aA | 62.93 ± 0.13cC |

| Tp | 76.68 ± 0.24bB | 79.62 ± 0.10aA | 68.20 ± 0.005cC |

| Tc | 81.44 ± 0.26bB | 84.79 ± 0.15aA | 74.12 ± 0.26cC |

| ΔHg (J/g) | 5.95 ± 0.21aA | 5.05 ± 0.26bB | 4.43 ± 0.006cC |

| (Cooled) To | 63.92 ± 0.42aA | 64.47 ± 0.35aAB | 61.46 ± 0.16bB |

| Tp | 69.30 ± 0.42aAB | 70.60 ± 0.14aA | 67.70 ± 0.31bB |

| Tc | 78.82 ± 0.24aA | 79.96 ± 0.08aA | 74.94 ± 0.46bB |

| ΔHr (J/g) | 1.45 ± 0.02Bb | 2.54 ± 0.35Aa | 0.87 ± 0.03Bc |

| RVA (RVU) | |||

| Peak viscosity (PV) | 200.3 ± 1.6bB | 249.8 ± 1.5aA | 249.4 ± 1.3aA |

| Trough viscosity (TV) | 132.0 ± 1.1cC | 198.3 ± 1.4aA | 157.7 ± 1.5bB |

| Breakdown viscosity (BDV) | 68.3 ± 2.7bB | 51.1 ± 0.1aA | 92.1 ± 2.1cC |

| Final viscosity (FV) | 251.8 ± 2.1cC | 359.5 ± 2.4aA | 280.2 ± 2.5bB |

| Setback viscosity (STV) | 51.5 ± 0.4bB | 110.1 ± 0.9aA | 30.4 ± 0.5cC |

| Pasting temperature (°C) | 72.1 ± 0.5bB | 73.7 ± 0.5aA | 68.2 ± 0.3cC |

| Gel texture | |||

| Fracture (N) | ND | 6.01 ± 0.05aA | ND |

| Hardness1 (N) | 3.16 ± 0.005bB | 6.09 ± 0.08aA | 1.01 ± 0.001cC |

| Adhesiveness (mJ) | 2.65 ± 0.07aA | 2.558 ± 0.08abA | 2.34 ± 0.06bA |

| Hradness2 (N) | 2.55 ± 0.05bB | 4.91 ± 0.06aA | 0.88 ± 0.003cC |

| Vermicelli properties | |||

| Water% | 72.45 ± 0.26bB | 72.30 ± 0.42bB | 75.23 ± 0.21aA |

| Iodine value | 0.156 ± 0.021aA | 0.028 ± 0.004bB | 0.034 ± 0.005bB |

| Broken rate% | 8.2 ± 2.14cC | 10.6 ± 3.25bB | 32.5 ± 3.68aA |

| Sensory evaluation | |||

| Color | 8.5 ± 0.2aA | 8.2 ± 0.1aA | 8.5 ± 0.2aA |

| Odor | 8.3 ± 0.3abA | 8.1 ± 0.2bA | 8.7 ± 0.1aA |

| Appearance | 8.6 ± 0.28aA | 8.5 ± 0.14aA | 6.1 ± 0.3bB |

| Flavor and texture | 10.1 ± 0.3aA | 6.5 ± 0.2bB | 5.8 ± 0.3cC |

| Total score | 35.5 ± 1.0aA | 31.3 ± 1.0bB | 29.1 ± 0.8C |

Data represent mean ± SD; a-c/A-C scripts in the same row with different letters are significantly different by Duncan’s multiple range tests at p < 0.05/p < 0.01, respectively

ND no found; Z17 Zhongjiazao17 variety; X24 Xiangzaoxian 24; TJR A Thai Jasmine rice

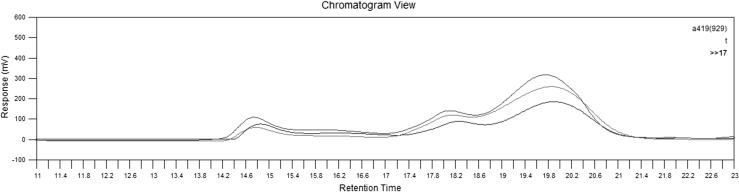

Amylose and amylopectin content

The first and the second peaks represent amylose and long chain amylopectin, and the third peak shows an intermediate to short chain amylopectin in a GPC/SEC chromatogram (Fig. 1). The proportion of amylose in the starch prepared from Z17, X24 and TJR flour was, 19.8, 21.1 and 8.8% respectively. All three flours shared a similar proportion (18–19%) of long amylopectin chains, while the low amylose content of TJR starch was compensated for by a high content of short chain amylopectin (Table 2). Amylopectin chain length and branch distribution are both expected to influence thermal, pasting and rheological properties (Jane et al. 1999). The distribution among the three classes of polymerization for Z17 starch showed 22.5% in DP6-10, 67.9% in DP11-20 and 9.9% in DP > 21, while the corresponding proportions for X24 were 19.2, 69.9 and 10.9%, and for TJR, they were 24.2, 66.2 and 9.0% respectively. The latter’s starch also contained 0.6% of class DP2-10. Thus Z17 starch included 3.3% more DP 6-10 amylopectin than X24 starch, and 3.0% less of the DP 11–25 chain molecules. The extra short chain amylopectins present in TJR starch could explain its particularly low AAC, since short chains are less effective in binding iodine. It indicated that distribution of amylose and amylopectin in a flour was an important determinant for vermicelli quality, but it did not to be correlated directly with low amylose content for vermicelli quality.

Fig. 1.

The gel permeation chromatography/size-exclusion chromatography output, illustrating differences in the amylose and amylopectin content of the starch prepared from three rice cultivars

SP, solubility and SEC

The SP performance of Z17, X24 and TJR flour was, respectively, 12.63, 11.28 and 13.55 g/g (Table 2). The correlation between SP and amylopectin content was high (0.86, data not shown), in line with the conclusion drawn by Singh et al. (2006) that amylopectin determines the swelling of cereal starch, with amylose acting to inhibit swelling. The solubility of the three flours was, respectively, 11.35, 10.23 and 13.28%. The amylose plays a role in the maintenance of the structure of rice starch granules (Seguchi et al. 2003). Therefore, the higher amylose content, the more compact starch granules and the starch is more difficult to overflow outside the granules with a low solubility value.

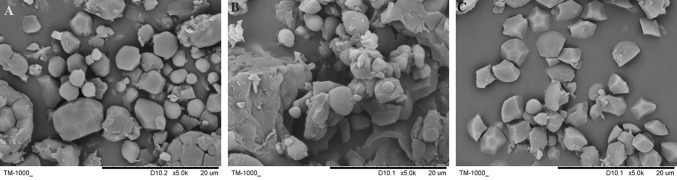

Typical SEM-derived micrographs of the three starches are shown in Fig. 2. TJR starch was dominated by polygonal granules (Fig. 2a), and X24 starch was denser and more agglomerated containing both polygonal and spherical granules (Fig. 2b), while Z17 starch lacked both granular structure and contained an abundance of protein bodies (Fig. 2c). Z17 had a high PC (12.1%), significantly higher than those of X24 (11.0%) and of TJR (7.7%), which implies that a high PC is required to ensure favorable vermicelli quality.

Fig. 2.

The flour of the three rice cultivars a TJR, b X24, and Z17 (c)

Thermal and pasting properties

Gelatinization follows thermal disruption of starch granules and thermal properties of starches are characterized in a form of DSC parameters as To, Tp, Tc and ΔH. To, Tp, Tc and ΔH from different rice cultivars differed significantly. X24 starch showed the highest To, Tp and Tc of 75.73, 79.62, and 84.79 °C, respectively, whereas TJR starch had the lowest To, Tp and Tc of 62.93, 68.20 and 74.12 °C, respectively. The profiles of Z17 starch were relatively similar to X24, although the latter swelled and gelatinized less easily than the former. Z17 starch’s To, Tp, Tc and ΔHg values were, respectively, 72.31 °C, 76.68 °C, 81.44 °C and 5.95 J/g. Z17 starch exhibited the maximum ΔH (5.95 J/g), whereas TJR had the lowest of 4.43 J/g (Table 2). ΔH is a measure of the overall crystalline of the amylopectin, i.e. the quality and quantity of starch crystal (Tester and Morrison 1990). The variation in ΔH from different varieties might be due to difference in proportion of amylose, and short side-chains amylopectin (Singh et al.2007). TJR harbored a high proportion (24.8%) of short amylopectin chains than that of Z17 (22.5%) and X24 (19.2%). Noda et al. (1998) also suggested that starches containing a high proportion of long amylopectin chains require a long gelatinization time, while those with a high proportion of short chains (DP 6–9) are rapidly gelatinized. Z17 flour had a significant high value of ΔH than those of X24 and TJR, indicating that Z17 may have a high stability of amylopection crystal. The results of DSC suggested that an optimal To, Tp, Tc should range in the context of, 72–76 °C, 76–80 °C and 81–85 °C, respectively for a good quality of vermicelli.

Gelatinized starch molecules can reform an ordered structure after stored at 4 °C for 10 days, a process referred to as retrogradation. The corresponding retrogradation transition temperatures (To, Tp, Tc) and enthalpy (ΔHr) are all significantly decreased compared to those of flour. The enthalpy (ΔHr) of Z17 starch was lower than that of X24, but higher than that of TJR, indicating vermicelli quality requires on an intermediate retrogradation capability.

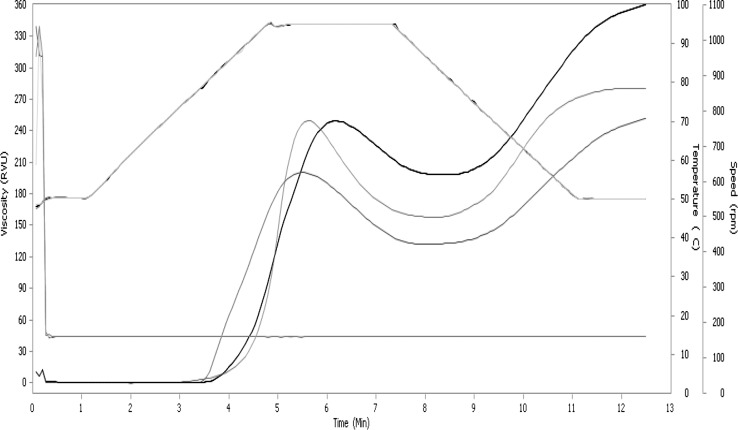

The RVA output reflects starch changes during the pasting process. RVA characteristics of trough, breakdown, final, setback viscosity and pasting temperature, except peak viscosity from different rice cultivars differed significantly (Table 2). Among the three cultivars, Z17 paste displayed the lowest peak, trough and final viscosity of 200.3 RVU, 132.0 RVU, and 251.8 RVU, respectively. The breakdown viscosity (68.3 RVU) of Z17 paste was significantly higher than that of X24 (51.1 RVU), while its setback viscosity (51.5 RVU) was lower (110.1 RVU). Although the pastes of the two varieties showed a very similar behavior in the late stage but Z17 showed a more rapid gelatinization (Fig. 3). A value of low setback is commonly interpreted as being due to the viscosity increasing as the paste cools (Fisher and Thompson 1997). The less aggregated the starch granules are, the lower the setback value becomes. A low breakdown viscosity is associated with starch of greater shearing strength and more stable physicochemical properties. The result showed that Z17 starch granules swelled rapidly during the gelatinization process, after which they were more readily disrupted by a high shear stress and tended to a slower rate of retrogradation. The TJR paste had a particularly low setback viscosity (30.4 RVU) and a high breakdown viscosity (92.1 RVU). The pasting of starch is greatly affected by the distribution of amylopectin branch chain lengths (Wani et al. 2012). The pasting temperatures of the three starches were 72.1 °C (Z17), 73.7 °C (X24) and 68.2 °C (TJR) respectively. The relatively low pasting temperature of TJR is likely due to its high content of very short (DP2-10) amylopectin chains (Hanashiro et al. 1996). It could be conclude that an intermediate setback viscosity of ~50 RVU, a breakdown viscosity of ~60 RVU and a pasting temperature of ~70 °C were required for producing a better quality of rice vermicelli.

Fig. 3.

The output of the rapid viscosity analyzer, illustrating differences in the pasting properties

Gel texture

The textural properties of the gels produced from the three flours varied (Table 2). The first hardness scores were 3.16 N (Z17), 6.09 N (X24) and 1.01 N (TJR), while the scores of the second cycle were 2.55 N, 4.91 N and 0.88 N respectively. The gel from X24 flour had a fracture value of 6.01 N, whereas neither of the other two gels fractured. The gels weren’t varied as greatly with respect to adhesiveness (2.34–2.65 mJ). Gel hardness is a consequence of retrogradation (Russell 1987). The More rigid gels formed by X24 were probably a consequence of its high content of long length (DP > 21) chains, since short chains inhibit retrogradation (Shi and Seib 1992). The result showed that an intermediate hardness is optimal for a high quality of vermicelli.

Conclusion

Wet vermicelli produced from Z17 flour was of higher quality than that produced from X24, and superior greatly to the product of TJR flour. Results indicated that flour with a low AAC is inappropriate for production of wet vermicelli. Although Z17 and X24 scored similarly for AAC, PC and GT, the two cultivars differed markedly with respect to a number of physiochemical properties, in particular with their AC and amylopection distribution, DSC parameters To, Tp and Tc, RVA pasting properties and gel texture. None of the parameters AAC, PC or GT, in single or combination, is sufficiently associated well with vermicelli quality, instead, other variables, such as AC, amylopectin distribution, thermal and pasting properties, gel texture and granule morphology must be considered as they contribute to the quality performance of vermicelli. Optimal vermicelli quality requires a high AAC and PC, an intermediate GT, GC, AC and pasting viscosity, a gel hardness equivalent to an RVA value of ~3 N, and a moderate retrogradation capacity (setback viscosity between 30 and 100 RVU). It suggest that some or all of the parameters of AC, amylopectin distribution, thermal and pasting property, gel texture and starch granule morphology should be used as selection traits for breeding rice cultivars suitable for production of vermicelli.

Footnotes

L. H. Xie and S. Q. Tang have contributed equally to this work.

References

- Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC) Official methods of analysis. 6. MD: AOAC; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ding WP, Wang YH, Xia WS. Determination on choosing standard of raw material in manufacturing rice noodle. Food Technol. 2004;10:24–26. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher DK, Thompson DB. Retrogradation of maize starch after thermal treatment within and above the gelatinization temperature range. Cereal Chem. 1997;74:344–351. doi: 10.1094/CCHEM.1997.74.3.344. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han HM, Cho JH, Koh BK. Processing properties of Korean rice varieties in relation to rice noodle quality. Food Sci Biotechnol. 2011;20(5):1277–1282. doi: 10.1007/s10068-011-0176-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hanashiro I, Abe J, Hizukuri S. A periodic distribution of the chain length of amylopectin as revealed by high-performance anion exchange chromatography. Carbohyd Res. 1996;283:151–159. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(95)00408-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hormdok R, Noomhorm A. Hydrothermal treatments of rice starch for improvement of rice noodle quality. Food Sci Technol. 2007;40(10):1723–1731. [Google Scholar]

- Jane J, Chen YY, Lee LF, McPherson AE, Wong KS, Radosavlijevic M, Kasemsuwan T. Effects of amylopectin branch chain length and amylose content on the gelatinization and pasting properties of starch. Cereal Chem. 1999;76:629–637. doi: 10.1094/CCHEM.1999.76.5.629. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kohlwey DE, Kendall JH, Mohindra RB. Using the physical properties of rice as a guide to formulation. Cereal Food World. 1995;40:728–732. [Google Scholar]

- Li CF, Luh BS. Rice snack foods. In: Luh BS, editor. Rice: production and utilization. Westport: Avi; 1980. pp. 690–711. [Google Scholar]

- Luo WB, Lin QL, Huang L, Wu Y, Xiao HX, Wang J. Study on physiochemical and sensory properties of fresh rice noodles produced by different varieties of indica rice. Food Mach. 2011;27(3):7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Agriculture People’s Republic of China. The Standard for the Method of the Rice Quality Determination. NY/T 147-1988

- Ministry of Agriculture People’s Republic of China. Determination of amylose content in rice-spectrophotometer method. NY/T 2639-2014

- Noda T, Takahata Y, Sato T, Suda I, Morishita T, Ishiguro K, Yamakawa O. Relationships between chain length distribution of amylopectin and gelatinization properties within the same botanical origin for sweet potato and buckwheat. Carbohyd Polym. 1998;37:153–158. doi: 10.1016/S0144-8617(98)00047-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea MG, Samuel MS, Konik CM, Morell MK. Fluorophore-assisted carbohydrate electrophoresis(FACE) of oligosaccharides: efficiency of labeling and high-resolution separation. Carbohyd Res. 1998;307:1–12. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6215(97)10085-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Russell PL. The ageing of gels from starches of different amylose/amylopectin content studied by differential scanning calorimetry. J Cereal Sci. 1987;6:147–158. doi: 10.1016/S0733-5210(87)80051-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seguchi M, Hayashi M, Sano Y, Hirano HY. Role of amylose in the maintenance of the configuration of rice starch granules. Starch/Stärke. 2003;55:524–528. doi: 10.1002/star.200300172. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shi YC, Seib PA. The structure of four waxy starches related to gelatinization and retrogradation. Carbohyd Res. 1992;227:131–145. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(92)85066-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh N, Kaur L, Sandhu KS, Kaur J, Nishinari K. Relationships between physicochemical, morphological, thermal, rheological properties of rice starches. Food Hydrocoll. 2006;20:532–542. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2005.05.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh N, Nakaura Y, Inouchi N, Nishinari Y. Fine structure, thermal and viscoelastic properties of starches separated from Indica rice cultivars. Starch-Starke. 2007;2007(59):10–20. doi: 10.1002/star.200600527. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tester RF, Morrison WR. Swelling and gelatinization of cereal starches, II. Waxy rice starches. Cereal Chem. 1990;67:558–563. [Google Scholar]

- Wani AA, Singh P, Shah MA, Schweiggert-Weisz U, Gul K, Wani IA. Rice starch diversity: effects on structural, morphological, thermal, and physicochemical properties-A review. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Safe. 2012;11(5):417–436. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-4337.2012.00193.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xie LH, He XY, Duan BW, Tang SQ, Luo J, Jiao GA, Shao GN, Wei XJ, Sheng ZH, Hu PS. Optimization of near-infrared reflectance model in measuring gelatinization characteristics of rice flour with a rapid viscosity analyzer-and differential scanning calorimeter(DSC) Cereal Chem. 2015;92(5):522–528. doi: 10.1094/CCHEM-08-14-0171-R. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoenyongbuddhagal S, Noomhorm A. Effect of physicochemical properties of high-amylose Thai rice flours on vermicelli quality. Cereal Chem. 2002;13:181–189. [Google Scholar]