Abstract

The shoulder is the most unstable joint in the human body. Traumatic anterior instability of the shoulder is a common condition, which, especially in young patients, is associated with high recurrence rates. The effectiveness of non-surgical treatments when compared to surgical ones is still controversial. The purpose of this study was to review the literature for current concepts and updates regarding the treatment of this condition.

Keywords: Joint instability, Orthopedic procedures, Recurrence, Shoulder dislocation, Shoulder joint

Resumo

A articulação do ombro é a mais instável do corpo humano. Sua instabilidade anterior de causa traumática é uma condição comum e com alta taxa de recidiva em pacientes jovens. A eficácia do tratamento conservador comparado com o tratamento cirúrgico, em suas diversas abordagens, ainda é debatida. O propósito deste estudo foi revisar a literatura, rever conceitos e últimas atualizações sobre o tratamento dessa afecção.

Palavras-chave: Instabilidade articular, Procedimentos ortopédicos, Recidiva, Luxação do ombro, Articulação do ombro

Introduction

The first episode of shoulder dislocation (primary dislocation) has an incidence of 1.7% in the general population. Among the different types of this joint instability, the anterior dislocation due to trauma is the most common type, corresponding to more than 90% of the cases.1, 2, 3 On this topic, Hovelius et al. developed three studies of great relevance. In the first, 257 patients were followed for a prospective 10 years after primary shoulder dislocation, and found a 49% recurrence rate. The second study, which followed the first (but this time with a 25-year follow-up), had two important results: (1) 72% of the patients with less than 22 years at the time of the primary dislocation progressed with recurrence, whereas this rate was only 27% in those older than 30 years; (2) almost half of the cases of primary dislocation occurred between 15 and 29 years.

In the third study, from 2008, Hovelius et al. were awarded a prize for research on the development of arthrosis in the same population of the second study. Of the group that progressed with instability, 29% developed mild arthrosis, 9% had moderate arthrosis, and 17% had severe arthrosis. In contrast, 18% of the patients, who had only one episode of dislocation, developed moderate to severe arthrosis. Detailed evaluation of the subgroups allowed the identification of three risk factors for the development of arthrosis: under 25 years of age at the time of the primary dislocation, alcoholism and high-energy sports. It is important to note that even patients who had only one episode of dislocation also present risks of developing arthrosis.4, 5, 6 Due to the anatomical peculiarities and the controversies about the treatment of primary dislocation, besides the high recurrence rate in young patients, we will address the most important aspects that will help us understand and treat this condition.

Primary dislocation non-surgical treatment

In the case of acute anterior primary dislocation, the most preferably used treatment is the reduction of the joint and its immobilization, followed by a variable period of rehabilitation to restore the range of motion and muscle strength around the shoulder.7

The most frequent complication, a reason for subsequent instability, is the avulsion of the anteroinferior portion of the glenoid labrum, and the lower margin of the glenoid fossa, known as Bankart lesion.8, 9 If it heals, which can occur in up to 50–80% of the time, the recurrence becomes, in theory, less frequent.10 It is therefore debated whether the duration and position of the shoulder immobilization are factors capable of influencing labrum healing.

A meta-analysis by Paterson et al., which included nine studies with levels I and II evidence, showed no benefit in immobilization for more than one week. However, it showed a lower tendency of recurrence with immobilization in lateral and major rotation if the patient's age was over 30 years.11 In 1999, Itoi et al. proposed that this initial lateral rotation immobilization would promote, by ligamentotaxis, a better reduction of the Bankart lesion and, therefore, higher healing rates.12

In 2003, Itoi et al.13 published a comparative clinical study between two groups of 20 patients each. The results showed a significant reduction in the rate of recurrence in those immobilized in lateral rotation for three weeks, when compared with those in medial rotation, especially in patients under 30 years. In 2007, the same authors conducted a similar research, but this time in a larger population (159 patients) and the results corroborated the findings of the first survey.14 More recently, in 2010, Taskoparan et al. also found favorable results for lateral immobilization (in this study, it was maintained at ten degrees for three weeks, and was removed only for personal hygiene).15

In contrast, in 2009 Finestone et al. did not find differences in recurrence rates when immobilizing 51 patients during four weeks (27 of them in lateral rotation of 15 to 20 degrees and 24 in medial rotation). Liavaag et al. published a study with 188 patients in 2011 – 95 patients immobilized in medial rotation and 93 in 15-degree lateral rotation for three weeks – and did not find differences between the two groups.16, 17, 18 The systematic review (which also included these latter two studies) developed by Patrick et al.10 did not show a decrease in recurrence with lateral rotation immobilization. However, in a new study in 2015, Itoi et al.19 show that the best position for injury reduction would be in 30-degree abduction with 60-degree lateral rotation, and that above 30-degree lateral rotation we already find reduction of the anterior lesion, but not of the inferior one. It may be finally argued that the 10–20 degrees of rotation used in the other studies were insufficient for injury reduction. Another hypothesis is that the joint hematoma would prevent the coaptation of the labrum lesion to its bed, and that the joint drainage could facilitate its coaptation.10, 19, 20

Finally, we can see that the existing publications to date do not support, with sufficient scientific evidence, the best period and the best position for immobilization; new studies are necessary to determine the best way for non-surgical management of this condition.

Primary dislocation surgical treatment

The indication of surgical treatment in traumatic primary dislocation is controversial.

Several authors have demonstrated favorable results for surgical stabilization after previous traumatic primary dislocation in young and active patients, in order to avoid or decrease recurrence rates.21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27 Between August 2000 and October 2008, 14 shoulders were treated, of 14 patients, by the Shoulder and Elbow Group of Santa Casa de São Paulo. Satisfactory results (with 100% excellent results) were obtained in all cases, according to the Rowe evaluation criterion.28 However, this strategy unnecessarily exposes some patients to surgical risk, because not all of them would progress with recurrences. On the other hand, we must remember that a recurrence can lead to an increase in osteocartilaginous lesions and lesions of the shoulder stabilizing ligaments.6, 23, 29

Thus, it is difficult to decide which is the best therapeutic indication. It should, therefore, be individualized, based on several individual characteristics, through discussion of results with the patient. Nowadays patients are increasingly better informed and want to base their decisions on solid evidence. We should always consider the patient's age, dominance, sport modality, and type of work activity. Climbers and surfers, for example, are at risk of death (falling or drowning) if they dislocate a shoulder during their activities. Professional athletes may also have their surgical procedure advanced or postponed based on their competition schedules.29, 30

Habermeyer31 introduced the Severity Shoulder Instability Score (SSIS). It uses some risk factors as criteria for recurrence. Its goal is to facilitate the decision between non-surgical and surgical treatment. Among the criteria, there are: patient's age, sports modality practiced, type of lesion found in the glenoid cavity (Bankart lesion associated or not with glenoid fracture and/or SLAP injury), mechanism of trauma, presence of other associated lesions (rotator cuff and Hill Sachs lesions), presence of generalized ligament hyperlaxity, type of dislocation reduction (whether spontaneous or assisted), and the degree of patient reliability to comply with a rehabilitation protocol. When applying this score in a group of 80 patients, Habermeyer31 obtained 2.9% of recurrence in patients treated surgically and 10.9% in those treated non-surgically.31

Open versus arthroscopic repair of a labrum lesion

Recurrent dislocations occur between 25% and 100% of all cases submitted to conservative treatment.5, 9, 21, 22, 32, 33 However, surgical treatment reduces the risk of recurrence by 6–22%.21, 22, 33, 34, 35 Although the aim of surgical treatment is to repair the injured structures to restore the physiological stability of the glenohumeral joint, there is still doubt as to the best method of repair.36

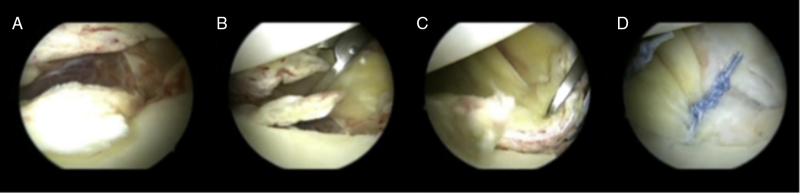

There is much discussion of the methods of approach (open or arthroscopic) for the fixation of the Bankart lesion.37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43 The arguments in favor of open repair are that it allows the surgeon to perform a more anatomical labrum repair, and the positioning of anchors in a safer direction. Those in favor of arthroscopy (Fig. 1), in their turn, argue that there is a reduction of complications when compared to open surgery, such as a higher infection rate, greater bleeding, subscapular dehiscence and arthrofibrosis, with equivalent and faster repair.38, 40, 41, 42 Chalmers et al.,36 in 2015, published a systematic review of eight meta-analyzes comparing the results of these two therapeutic methods. In it, the meta-analyzes were scored (from 0 to 18 points) according to a tool called Quorom (Quality of Reporting of Meta-Analyzes) (the higher the score, the better the level of evidence). Two meta-analyses published before 2007, with a Quorom score of 15 and 13, showed fewer recurrences after repair. The three meta-analyses conducted in 2007, with scores of 14, 16 and 16, were discordant. The last three, published after 2008 (scores of 12, 16 and 17), did not find differences in recurrence rates when comparing the two methods. Note that among these there is the meta-analysis with the best level of evidence (17 points)36 (Table 1).34, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46 Mohtadi et al.40 performed a prospective and randomized clinical trial (level I evidence) comparing the results of open repair with those of the arthroscopic repair. In this trial, 196 patients were followed for two years after surgery. They concluded that there was no difference between the two groups regarding quality of life, but that open repair results in a significant reduction in the risk of recurrence. Subgroup analysis showed that this decrease in risk is even more important in the group of patients younger than 25 years and who have Hill-Sachs lesion visible on radiography.

Fig. 1.

Left shoulder, joint view through the posterior portal. (A) Bankart lesion; (B and C) preparation for lesion repair; (D) Bankart lesion arthroscopic repair.

Table 1.

Systematic review comparing open repair and arthroscopic repair of Bankart lesions regarding the number of recurrences.

| Authors | Publication date | Quorom | Lower number of recurrences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Freedman et al.44 | July 2004 | 15 | Open repair |

| Mohtadi et al.40 | June 2005 | 13 | Open repair |

| Hobby et al.34 | September 2007 | 14 | Discordant |

| Lenters et al.45 | February 2007 | 16 | Discordant |

| Ng et al.41 | June 2007 | 16 | Discordant |

| Pulavarti et al.46 | October 2009 | 16 | No differences |

| Petrera et al.42 | March 2010 | 17 | No differences |

In a level I evidence paper published in 2006, Bottoni et al.37 did not find differences in recurrence rates between the two techniques but obtained shorter surgical time and better range of motion with the arthroscopic approach. In the group submitted to open repair, two of the 29 patients experienced recurrences. In the other group (32 arthroscopies), there was only one recurrence.37

Bankart lesion open repair versus open bone block procedure

Helfet47 was the one who described the procedure popularized by Bristow, which consists of transferring the tip of the coracoid process to the anterior border of the glenoid through the fibers of the subscapularis muscle; in this muscle, the transfer is fixed to the joint capsule without the use of screws. Latarjet48 and Patte et al.49 modified the technique in two ways: (1) the positioning of the coracoid graft, which put in to a “lying” position (with its largest axis in a vertical position; parallel to the articular surface of the glenoid) and (2) its fixation through two compression screws.48, 49, 50 Nowadays, this is the most commonly used technique.49

Although this procedure has been criticized,51, 52 good results have been found in several studies. Stability is believed to be achieved by a triple mechanism of humeral head restraint: that of the “brace”, in which the coracobrachialis and short head of the biceps tendons and the lower portion of the subscapularis restrain the anteroinferior joint capsule; that of the bone block procedure, in which the transferred choroidal process functions as an extension of the glenoid cavity; and that of ligament reinforcement, since the stump of the coracoacromial ligament is sutured to the joint capsule.49

Hovelius et al.,53 in 2012, described the results of 97 consecutive cases of patients undergoing Latarjet procedure compared to 88 cases of open repair of the Bankart lesion; the latter was performed with anchors or through transglenoidal orifices. With a 17-year postoperative follow-up, recurrence occurred in 14% of the patients (13 of 97 cases) undergoing Latarjet procedure, with a satisfaction index above 95%. On the other hand, of the 88 cases undergoing Bankart lesion repair, 25 progressed with recurrence (28%), with 80% satisfaction. Among the findings of this study, the best scores were Dash (Disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand), Wosi (Western Ontario Shoulder Instability Index) and SSV (subjective shoulder value) scores. Finally, they came to two conclusions: (1) the Latarjet procedure leads to better subjective results and provides greater stability to the shoulder; (2) the lip repair through transglenoidal orifices was superior to that performed with anchors.53

Arthroscopic repair of Bankart lesion versus open bone block procedure

Although being rather variable, the rate of recurrence of the arthroscopic repair of the Bankart lesion is still considered an effective procedure with good reproducibility, especially when the patient is well selected.

Thus, Balg and Boileau54 developed the Instability Severity Index Score (ISIS) in 2006 as a means for determining which patients should benefit from an arthroscopic anchorage Bankart repair, or Latarjet procedure. In a prospective study the researchers identified six risk factors that when combined in a scoring system result in unacceptable high rates of Bankart arthroscopic repair failure. Patients with a score above six had 70% of recurrence, whereas in patients with a score equal to or lower than six fell to 10%.54 According to the ISIS, patients with a score above six should undergo the Latarjet procedure and with six or less the Bankart's arthroscopic repair.

In 2013, Rouleau et al.,55 in a multicenter study with 114 consecutive cases, validated ISIS. The results showed that ISIS is highly reproducible, that is, easy to apply; quality of life questionnaires did not correlate with ISIS, also showing that patients with ISIS greater than six had a higher number of recurrences before surgery; and that in the medical centers where it was applied, it was an indicator of which patients would require more complex surgeries, such as Hill-Sachs lesion filling (remplissage) or a Latarjet procedure.55

It was observed that ISIS was used by authors, but it has been adapted. Some authors, such as Boileau, have described that some patients with ISIS greater than three, and glenoid cavity bone defects were candidates for Bankart-Britow-Latarjet arthroscopic surgery.56 Thomazeau et al. used a score of less than or equal to four to indicate arthroscopic surgery.57

Like Boileau et al.,56 there is a current trend toward the indication of bone blocks (Latarjet, Eden-Hybinette or Bristow surgeries) when there is glenoid erosion.58, 59 Defects greater than 20% of the anteroposterior joint diameter are considered the limit for several authors.58, 59, 60 However, both this value and the erosion measurement technique are still topics of debate.61 For some,58, 59, 60 the practice of competitive sports is an independent risk factor for recurrence and, therefore, is also an independent indicator for bone blocks.

Despite providing fewer recurrences, “bone blocks” are not free of complications. Paladini et al.62 showed a loss of the isometric contraction force of the subscapularis after their L-shaped tenotomy and, therefore, they recommend that the glenoid approach (which is necessarily performed through the subscapular) be made longitudinally (by separation of their fibers). Subscapular muscle deficiency explains the loss of active medial rotation after surgery.

Other possible complications are loss of lateral rotation that leads to glenohumeral arthrosis and those related to graft positioning, which should be done as close as possible to the glenoid joint surface (less than 10 mm of medialization and below the “equator line”). If its fixation is too medial or too high, for example, there may be therapeutic failure (with maintenance of instability). A case series by Hovelius et al. showed poor positioning in 42% of times (32% of times above the “equator line” and 6% too medial).53 Overhanging grafts, in their turn, can cause arthrosis regardless of other factors.63

Bipolar defects

It is accepted that in defects impairing the glenoidal cavity in 25% or more of the inferior diameter, surgical treatment for instability with the use of bone graft, coracoid or iliac graft, or allograft should be performed.64 However, the approach to bipolar defects is not clear when the defect is in the glenoid cavity and humeral head simultaneously (Hill-Sachs lesion).65

Greis et al.65 demonstrated that the greater the bone loss of the glenoid cavity, the greater the contact pressure of the humeral head against the glenoid cavity. For example, the labral lesion reduces the contact area by 7% and 15% and increases the contact pressure by 8% and 20%. A loss of 30% of the glenoid cavity increases the pressure in the anteroinferior region by 300% and 400%, and considerably increases the risk of recurrence.

Burkhart and DeBeer66 identified the risk of arthroscopy failure when, during the procedure, it is observed that the appearance of the glenoid cavity has the shape of an “inverted pear”. On the humeral side, Hill-Sachs lesions, in which engaging at 90 degrees of abduction and lateral rotation takes place, are considered as risky lesions only for the performance of Bankart lesion repair.

Yamamoto et al.,67 in 2007 demonstrated the contact area of the humeral head and the glenoid cavity from the point of glenohumeral dislocation, and defined this zone of contact as glenoid track. This intact region ensures bone stability.

The intraoperative test for engaging performed prior to the arthroscopic repair of the Bankart lesion is overestimated because ligament insufficiency allows for a greater translocation of the humeral head.68 The test after Bankart lesion repair, defined by Kurokawa as true “engaging”, leads to the risk of damage to the repair performed. Kurokawa et al.69 evaluated 100 shoulders, in 94 cases there were Hill-Sachs lesions, only seven cases (7.4%) were defined as true engaging. Parke et al.70 evaluated 983 shoulders, found 70 cases of true “engaging” (7.1%) of the cases. Before Bankart lesion repair, an incidence of engaging between 34% and 46% of the cases is described.

For this evaluation, without the risk of causing overload to Bankart's injury repair, we use the glenoid track. Through a tomographic study we evaluated if the medial margin of the Hill-Sachs lesion is in contact with the glenoid track; then, the lesion is called on track; however, if the Hill-Sachs lesion is more medial than the glenoid track, it is called off track, in which the risk of engaging is greater.68

This evaluation leads to four categories: the first includes patients with glenoidal cavity defects <25%, and with Hill-Sachs on track lesion; the second, patients with glenoid cavity defects <25% and Hill-Sachs off-track lesion, the third of patients with defects ≥25% and with Hill-Sachs on track lesion, and the fourth, patients with defects ≥25% and Hill-Sachs off-track lesions.68

Therefore, based on the report above, the suggestion is to treat patients of the first category with arthroscopic repair of the Bankart lesion; the second, with complementation of the treatment with the remplissage technique; the third, with Latarjet procedure, and the fourth with Latarjet procedure associated or not with the Hill-Sachs lesion filling (remplissage) or bone graft of the humeral head68 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Categories of anterior instability and recommended treatment.

| Groups | Glenoid fossa defect | Hill-Sachs lesion | Recommended treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | <25% | On track | Arthroscopic repair of Bankart lesion |

| 2 | <25% | Off track | Arthroscopic repair of Bankart lesion + remplissage |

| 3 | ≥25% | On track | Latarjet procedure |

| 4 | ≥25% | Off track | Latarjet procedure with or without humeral head procedure (remplissage or graft) |

Hill-Sachs lesion treatment

In 1940, Hill and Sachs were the first to describe the posterolateral fracture of the humeral head by impaction against the glenoid, which occurs secondary to the anterior dislocation of the shoulder.71 Its incidence in the primary dislocation is 47–80% and, in the relapsing dislocation, of up to 93%. Several treatments have been used72; currently, the technique of lesion filling with the infraspinatus tendon (remplissage) has become the most popular treatment.73 In 2014, Buza et al.74 described a systematic review with the inclusion of 167 patients undergoing the remplissage technique, with a mean follow-up of 26.8 months, in which there was a small lateral rotation deficit (57.2° to 54.6°), and 5.4% of recurrences.

A retrospective evaluation by Boileau et al. showed that he used remplissage in 47 of 459 patients (10.2%) in his series. The mean lateral rotation deficit was 8 degrees. Of the 41 patients who practiced sports, 37 returned to practice (90%), with 28 at the same sports level (including pitchers). The recurrence rate was only 2%.75

Gracitelli et al. published a retrospective analysis of ten shoulders simultaneously undergoing remplissage and Bankart lesion repair (both by arthroscopy). The indication was for lesions with less than 25% impaction of the humeral head, and with engaging during the arthroscopic evaluation. The results were improved Rowe scores from 22.5 to 80.5, and UCLA from 18.0 to 31.1 with two cases of recurrence, one dislocation and one subluxation.76

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Paper developed at the Faculdade de Ciências Médicas da Santa Casa de São Paulo (FCM-SCSP), Departamento de Ortopedia e Traumatologia, São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

References

- 1.Romeo A.A., Cohen B.S., Carreira D.S. Traumatic anterior shoulder instability. Orthop Clin North Am. 2001;32(3):399–409. doi: 10.1016/s0030-5898(05)70209-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maffulli N., Longo U.G., Gougoulias N., Loppini M., Denaro V. Long-term health outcomes of youth sports injuries. Br J Sports Med. 2010;44(1):21–25. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2009.069526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goss T.P. Anterior glenohumeral instability. Orthopedics. 1988;11(1):87–95. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19880101-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hovelius L., Augustini B.G., Fredin H., Johansson O., Norlin R., Thorling J. Primary anterior dislocation of the shoulder in young patients. A ten-year prospective study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78(11):1677–1684. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199611000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hovelius L., Olofsson A., Sandström B., Augustini B.G., Krantz L., Fredin H. Nonoperative treatment of primary anterior shoulder dislocation in patients forty years of age and younger. a prospective twenty-five-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(5):945–952. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hovelius L., Saeboe M. Neer Award 2008: arthropathy after primary anterior shoulder dislocation – 223 shoulders prospectively followed up for twenty-five years. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(3):339–347. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jakobsen B.W., Johannsen H.V., Suder P., Søjbjerg J.O. Primary repair versus conservative treatment of first-time traumatic anterior dislocation of the shoulder: a randomized study with 10-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2007;23(2):118–123. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rowe C.R., Patel D., Southmayd W.W. The Bankart procedure: a long-term end-result study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1978;60(1):1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taylor D.C., Arciero R.A. Pathologic changes associated with shoulder dislocations. Arthroscopic and physical examination findings in first-time, traumatic anterior dislocations. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25(3):306–311. doi: 10.1177/036354659702500306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vavken P., Sadoghi P., Quidde J., Lucas R., Delaney R., Mueller A.M. Immobilization in internal or external rotation does not change recurrence rates after traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(1):13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2013.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paterson W.H., Throckmorton T.W., Koester M., Azar F.M., Kuhn J.E. Position and duration of immobilization after primary anterior shoulder dislocation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(18):2924–2933. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.00631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Itoi E., Hatakeyama Y., Urayama M., Pradhan R.L., Kido T., Sato K. Position of immobilization after dislocation of the shoulder. A cadaveric study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81(3):385–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Itoi E., Hatakeyama Y., Kido T., Sato T., Minagawa H., Wakabayashi I. A new method of immobilization after traumatic anterior dislocation of the shoulder: a preliminary study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12(5):413–415. doi: 10.1016/s1058-2746(03)00171-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Itoi E., Hatakeyama Y., Sato T., Kido T., Itoi E., Hatakeyama Y. Immobilization in external rotation after shoulder dislocation reduces the risk of recurrence. A randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(10):2124–2131. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taşkoparan H., Kılınçoğlu V., Tunay S., Bilgiç S., Yurttaş Y., Kömürcü M. Immobilization of the shoulder in external rotation for prevention of recurrence in acute anterior dislocation. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2010;44(4):278–284. doi: 10.3944/AOTT.2010.2274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finestone A., Milgrom C., Radeva-Petrova D.R., Rath E., Barchilon V., Beyth S. Bracing in external rotation for traumatic anterior dislocation of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91(7):918–921. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B7.22263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liavaag S., Brox J.I., Pripp A.H., Enger M., Soldal L.A., Svenningsen S. Immobilization in external rotation after primary shoulder dislocation did not reduce the risk of recurrence: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(10):897–904. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.00416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jadad A.R., Moore R.A., Carroll D., Jenkinson C., Reynolds D.J., Gavaghan D.J. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Itoi E., Kitamura T., Hitachi S., Hatta T., Yamamoto N., Sano H. Arm abduction provides a better reduction of the Bankart lesion during immobilization in external rotation after an initial shoulder dislocation. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(7):1731–1736. doi: 10.1177/0363546515577782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seybold D., Schliemann B., Heyer C.M., Muhr G., Gekle C. Which labral lesion can be best reduced with external rotation of the shoulder after a first-time traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation? Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2009;129(3):299–304. doi: 10.1007/s00402-008-0618-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arciero R.A., Wheeler J.H., Ryan J.B., McBride J.T. Arthroscopic Bankart repair versus nonoperative treatment for acute, initial anterior shoulder dislocations. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22(5):589–594. doi: 10.1177/036354659402200504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bottoni C.R., Wilckens J.H., DeBerardino T.M., D’Alleyrand J.C., Rooney R.C., Harpstrite J.K. A prospective, randomized evaluation of arthroscopic stabilization versus nonoperative treatment in patients with acute, traumatic, first-time shoulder dislocations. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30(4):576–580. doi: 10.1177/03635465020300041801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeBerardino T.M., Arciero R.A., Taylor D.C., Uhorchak J.M. Prospective evaluation of arthroscopic stabilization of acute, initial anterior shoulder dislocations in young athletes. Two- to five-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(5):586–592. doi: 10.1177/03635465010290051101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kirkley A., Werstine R., Ratjek A., Griffin S. Prospective randomized clinical trial comparing the effectiveness of immediate arthroscopic stabilization versus immobilization and rehabilitation in first traumatic anterior dislocations of the shoulder: long-term evaluation. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(1):55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2004.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Law B.K., Yung P.S., Ho E.P., Chang J.J., Chan K.M. The surgical outcome of immediate arthroscopic Bankart repair for first time anterior shoulder dislocation in young active patients. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2008;16(2):188–193. doi: 10.1007/s00167-007-0453-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Owens B.D., DeBerardino T.M., Nelson B.J., Thurman J., Cameron K.L., Taylor D.C. Long-term follow-up of acute arthroscopic Bankart repair for initial anterior shoulder dislocations in young athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(4):669–673. doi: 10.1177/0363546508328416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robinson C.M., Jenkins P.J., White T.O., Ker A., Will E. Primary arthroscopic stabilization for a first-time anterior dislocation of the shoulder. A randomized, double-blind trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(4):708–721. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miyazaki A.N., Fregoneze M., Santos P.D., da Silva L.A., do Val Sella G., Botelho V. Assessment of the results from arthroscopic surgical treatment for traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation: first episode. Rev Bras Ortop. 2015;47(2):222–227. doi: 10.1016/S2255-4971(15)30090-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bishop J.A., Crall T.S., Kocher M.S. Operative versus nonoperative treatment after primary traumatic anterior glenohumeral dislocation: expected-value decision analysis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(7):1087–1094. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brophy R.H., Marx R.G. The treatment of traumatic anterior instability of the shoulder: nonoperative and surgical treatment. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(3):298–304. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Habermeyer P. 11° Congresso Mundial ICSES; Edinburgh: 2010. The severity shoulder instability score (SSIS): a guide for therapy option for first traumatic shoulder dislocation. Dissertação. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marans H.J., Angel K.R., Schemitsch E.H., Wedge J.H. The fate of traumatic anterior dislocation of the shoulder in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74(8):1242–1244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Robinson C.M., Howes J., Murdoch H., Will E., Graham C. Functional outcome and risk of recurrent instability after primary traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation in young patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(11):2326–2336. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.01327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hobby J., Griffin D., Dunbar M., Boileau P. Is arthroscopic surgery for stabilisation of chronic shoulder instability as effective as open surgery? A systematic review and meta-analysis of 62 studies including 3044 arthroscopic operations. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89(9):1188–1196. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B9.18467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Magnusson L., Ejerhed L., Rostgård-Christensen L., Sernert N., Eriksson R., Karlsson J. A prospective, randomized, clinical and radiographic study after arthroscopic Bankart reconstruction using 2 different types of absorbable tacks. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(2):143–151. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2005.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chalmers P.N., Mascarenhas R., Leroux T., Sayegh E.T., Verma N.N., Cole B.J. Do arthroscopic and open stabilization techniques restore equivalent stability to the shoulder in the setting of anterior glenohumeral instability? A systematic review of overlapping meta-analyses. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(2):355–363. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2014.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bottoni C.R., Smith E.L., Berkowitz M.J., Towle R.B., Moore J.H. Arthroscopic versus open shoulder stabilization for recurrent anterior instability: a prospective randomized clinical trial. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(11):1730–1737. doi: 10.1177/0363546506288239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harris J.D., Gupta A.K., Mall N.A., Abrams G.D., McCormick F.M., Cole B.J. Long-term outcomes after Bankart shoulder stabilization. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(5):920–933. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2012.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim S.H., Ha K.I., Kim S.H. Bankart repair in traumatic anterior shoulder instability: open versus arthroscopic technique. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(7):755–763. doi: 10.1053/jars.2002.31701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mohtadi N.G., Bitar I.J., Sasyniuk T.M., Hollinshead R.M., Harper W.P. Arthroscopic versus open repair for traumatic anterior shoulder instability: a meta-analysis. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(6):652–658. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2005.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ng C., Bialocerkowski A., Hinman R. Effectiveness of arthroscopic versus open surgical stabilisation for the management of traumatic anterior glenohumeral instability. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2007;5(2):182–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-6988.2007.00064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Petrera M., Patella V., Patella S., Theodoropoulos J. A meta-analysis of open versus arthroscopic Bankart repair using suture anchors. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18(12):1742–1747. doi: 10.1007/s00167-010-1093-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang C., Ghalambor N., Zarins B., Warner J.J. Arthroscopic versus open Bankart repair: analysis of patient subjective outcome and cost. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(10):1219–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Freedman K.B., Smith A.P., Romeo A.A., Cole B.J., Bach B.R. Open Bankart repair versus arthroscopic repair with transglenoid sutures or bioabsorbable tacks for recurrent anterior instability of the shoulder: a meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(6):1520–1527. doi: 10.1177/0363546504265188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lenters T.R., Franta A.K., Wolf F.M., Leopold S.S., Matsen F.A., III Arthroscopic compared with open repairs for recurrent anterior shoulder instability. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(2):244–254. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.01139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pulavarti R.S., Symes T.H., Rangan A. Surgical interventions for anterior shoulder instability in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;7(4) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005077.pub2. CD005077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Helfet A.J. Coracoid transplantation for recurring dislocation of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1958;40-B(2):198–202. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.40B2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Latarjet M. Treatment of recurrent dislocation of the shoulder. Lyon Chir. 1954;49(8):994–997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Patte D., Bernageau J., Rodineau J., Gardes J.C. Unstable painful shoulders (author's transl) Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 1980;66(3):157–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Walch G. Chronic anterior glenohumeral instability. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1996;78(4):670–677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Young D.C., Rockwood C.A., Jr. Complications of a failed Bristow procedure and their management. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73(7):969–981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boileau P., Mercier N., Old J. Arthroscopic Bankart-Bristow-Latarjet. (2B3) Procedure: how to do it and tricks to make it easier and safe. Orthop Clin North Am. 2010;41(3):381–392. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hovelius L., Sandström B., Olofsson A., Svensson O., Rahme H. The effect of capsular repair, bone block healing, and position on the results of the Bristow-Latarjet procedure (study III): long-term follow-up in 319 shoulders. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(5):647–660. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Balg F., Boileau P. The instability severity index score. A simple pre-operative score to select patients for arthroscopic or open shoulder stabilisation. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89(11):1470–1477. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B11.18962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rouleau D.M., Hébert-Davies J., Djahangiri A., Godbout V., Pelet S., Balg F. Validation of the instability shoulder index score in a multicenter reliability study in 114 consecutive cases. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(2):278–282. doi: 10.1177/0363546512470815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Boileau P., Mercier N., Roussanne Y., Thélu C.É., Old J. Arthroscopic Bankart-Bristow-Latarjet procedure: the development and early results of a safe and reproducible technique. Arthroscopy. 2010;26(11):1434–1450. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thomazeau H., Courage O., Barth J., Pélégri C., Charousset C., Lespagnol F. French Arthroscopy Society. Can we improve the indication for Bankart arthroscopic repair? A preliminary clinical study using the ISIS score. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2010;96(8 Suppl):S77–S83. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yamamoto N., Itoi E., Abe H., Kikuchi K., Seki N., Minagawa H. Effect of an anterior glenoid defect on anterior shoulder stability: a cadaveric study. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(5):949–954. doi: 10.1177/0363546508330139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Southgate D.F., Bokor D.J., Longo U.G., Wallace A.L., Bull A.M. The effect of humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligaments and humeral repair site on joint laxity: a biomechanical study. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(6):990–997. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2013.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bessiere C., Trojani C., Pélégri C., Carles M., Boileau P. Coracoid bone block versus arthroscopic Bankart repair: a comparative paired study with 5-year follow-up. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2013;99(2):123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2012.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Longo U.G., Loppini M., Rizzello G., Ciuffreda M., Maffulli N., Denaro V. Latarjet, Bristow and Eden-Hybinette procedures for anterior shoulder dislocation: systematic review and quantitative synthesis of the literature. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(9):1184–1211. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Paladini P., Merolla G., De Santis E., Campi F., Porcellini G. Long-term subscapularis strength assessment after Bristow-Latarjet procedure: isometric study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(1):42–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Torg J.S., Balduini F.C., Bonci C., Lehman R.C., Gregg J.R., Esterhai J.L. A modified Bristow-Helfet-May procedure for recurrent dislocation and subluxation of the shoulder. Report of two hundred and twelve cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987;69(6):904–913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gerber C., Nyffeler R.W. Classification of glenohumeral joint instability. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;(400):65–76. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200207000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Greis P.E., Scuderi M.G., Mohr A., Bachus K.N., Burks R.T. Glenohumeral articular contact areas and pressures following labral and osseous injury to the anteroinferior quadrant of the glenoid. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11(5):442–451. doi: 10.1067/mse.2002.124526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Burkhart S.S., De Beer J.F. Traumatic glenohumeral bone defects and their relationship to failure of arthroscopic Bankart repairs: significance of the inverted-pear glenoid and the humeral engaging Hill-Sachs lesion. Arthroscopy. 2000;16(7):677–694. doi: 10.1053/jars.2000.17715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yamamoto N., Itoi E., Abe H., Minagawa H., Seki N., Shimada Y. Contact between the glenoid and the humeral head in abduction, external rotation, and horizontal extension: a new concept of glenoid track. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16(5):649–656. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2006.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Di Giacomo G., Itoi E., Burkhart S.S. Evolving concept of bipolar bone loss and the Hill-Sachs lesion: from engaging/non-engaging lesion to on-track/off-track lesion. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(1):90–98. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kurokawa D., Yamamoto N., Nagamoto H., Omori Y., Tanaka M., Sano H. The prevalence of a large Hill-Sachs lesion that needs to be treated. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(9):1285–1289. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2012.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Parke C.S., Yoo J.H., Cho N.S., Rhee Y.G. 39th annual meeting of Japan Shoulder Society, Tokyo, October 5–6. 2012. Arthroscopic remplissage for humeral defect in anterior shoulder instability: is it needed? [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hill H.A., Sachs M.D. The grooved defect of the humeral head. Radiology. 1940;35:690–700. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Provencher M.T., Frank R.M., Leclere L.E., Metzger P.D., Ryu J.J., Bernhardson A. The Hill-Sachs lesion: diagnosis, classification, and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20(4):242–252. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-20-04-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bigliani L.U., Flatow E.L., Pollock R.G. Fractures of the proximal humerus. In: Rockwood C.A., Green D.P., Bucholz R.W., editors. Fractures in adults. 4th ed. Lippincott-Raven; Philadelphia: 1996. pp. 1055–1107. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Buza J.A., 3rd, Iyengar J.J., Anakwenze O.A., Ahmad C.S., Levine W.N. Arthroscopic Hill-Sachs remplissage: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(7):549–555. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Boileau P., Villalba M., Héry J.Y., Balg F., Ahrens P., Neyton L. Risk factors for recurrence of shoulder instability after arthroscopic Bankart repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(8):1755–1763. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gracitelli M.E., Helito C.P., Malavolta E.A., Neto A.A., Benegas E., Prada F.S. Results from filling remplissage arthroscopic technique for recurrent anterior shoulder dislocation. Rev Bras Ortop. 2015;46(6):684–690. doi: 10.1016/S2255-4971(15)30325-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]