Abstract

Purpose

The objective of this study was to compare the frequency of severe systemic, multi-organ involvement and toxic shock syndrome (TSS) in patients with Staphylococcus aureus (SA) and Group A β-haemolytic Streptococcus pyogenes (GABS) bone and joint infections.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed patients treated for septic arthritis or osteomyelitis at one children’s hospital between 2002 and 2009. The rates of intensive care unit (ICU) admission for methicillin-sensitive SA (MSSA), methicillin-resistant SA (MRSA) and GABS infections were compared, as were the lengths of stay, number of surgeries, operative procedures and cases of TSS.

Results

A total of 16 of 208 patients (7.7%) with culture-positive bone or joint infections were admitted to the ICU for critical illness: more commonly for patients with GABS infection (7/21 or 33%) than those with SA infection (6/132 or 5%) (odds ratio 10.55, 95% confidence interval 3.093 to 35.65, p = 0.0002). Patients with MRSA infections were significantly more likely to need ICU care than those with MSSA infection (p = 0.0009). Six of the ICU patients met the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention criteria for TSS. ICU patients with MRSA and GABS bone and joint infections had similar hospital courses: numerous surgeries (mean three per patient); procedures performed (mean 11 per patient); and prolonged hospital stays.

Conclusion

We found a greater likelihood of patients developing severe, multi-system involvement with bone and joint infections caused by GABS or MRSA when compared with MSSA. Early aggressive treatment of systemic shock and liberal decompressions of infected joints may limit the sequelae of these serious infections.

Keywords: Group A β-haemolytic Streptococcus, Staphyloccocus aureus, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, toxic shock syndrome

Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus (SA) and Group A β-haemolytic Streptococcus pyogenes (GABS) account for the majority of cases of paediatric bone and joint infections. SA causes 80% to 90% of paediatric bone infections and most joint infections while GABS accounts for approximately 10%.1-6 The mortality rate 100 years ago for septic arthritis associated with osteomyelitis in the Unites States exceeded 50%.7 With routine antibiotic treatment, the mortality rate in industrialised nations for septic arthritis dropped to nearly 0.2,8 However, GABS remains a virulent strain causing high morbidity and mortality. In 1989, Stevens et al9 reported a 30% mortality rate and in 1996, Davies et al10 reported an 81% mortality rate in adults with GABS toxic shock syndromes (TSS), despite aggressive antibiotic and supportive therapies. Mehta el al11 reported a 40% mortality rate in adults and teenage patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) with invasive GABS infections and others have reported an increased incidence of soft-tissue and bone infections and toxic shock caused by GABS.4,12-14 Few published reports of GABS bone and joint infections in children exist.4,15-18

TSS, first described in association with SA infection in 1978,19 was noted to occur most commonly in young women who were using highly absorbent tampons and was due to a staphylococcal exotoxin TSST-1. Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (STSS), associated with GABS infection, was first described in 1987.20 Both SA and GABS produce an extracellular protein, exotoxin, that acts as a super antigen, activating T-cells and potentially causing massive release of cytokines leading to clinical TSS. GABS also produces other toxins such as the M proteins; however, debate persists as to whether M proteins act as true super antigens.21 Clinical manifestations of TSS in children include hypotension and multi-organ involvement, with two or more of the following: renal impairment; coagulopathy; abnormal liver function tests; acute respiratory distress syndrome; generalised erythematous macular rash; or soft-tissue necrosis.22 The objective of this study was to determine the frequency of severe systemic and multi-organ involvement in patients who had bone and joint infections, comparing those with GABS infection with those with SA infection. We hypothesised that the rate of severe systemic involvement would not differ between the two aetiologic agents.

Patients and methods

The records of all patients admitted and treated at one children’s hospital for septic arthritis and osteomyelitis between 01 January 2002 and 31 December 2008 were retrospectively reviewed. Those included were diagnosed with septic arthritis or osteomyelitis of the spine or extremities via culture positive synovial fluid or bone aspirates, and/or a purulent appearance of synovial fluid with positive blood cultures, with pain, swelling and irritability related to the aspiration sites. Patients were excluded for the following reasons: age < 30 days or who had remained hospitalised from birth before the onset of their infection; had a likely diagnosis of juvenile arthritis, toxic synovitis, craniofacial osteomyelitis, myositis without joint or bone involvement, cellulitis; or were treated on an outpatient basis. No patient was excluded because of an immune-compromised state due to chemotherapy.

Operative reports, progress notes, interim summaries, discharge summaries and laboratory data were reviewed to determine causative organism. ICU admission, the total length of stay, the number of procedures during the index hospitalisation, the number of re-admissions and the total number of surgeries were recorded.

Statistical analysis

Variables were summarised using frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, and mean and standard deviation for continuous variables. Fisher’s exact test was used to determine significant difference between categorical variables, and Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to analyse differences between groups.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention criteria23,24 of STSS and TSS (Tables 1 and 2) were used to determine whether the patients admitted to the ICU with streptococcal and staphylococcal infections had STSS and TSS, respectively.

Table 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention case definition of streptococcal toxic shock syndrome24.

| Clinical signs |

|

| Laboratory signs |

|

Table 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention definition of staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome23.

| Clinical signs |

|

| Laboratory signs |

Negative results on the following tests, if obtained:

|

Patients with five of six required clinical findings were classified as probable TSS, as described by Lappin and Ferguson.21

Results

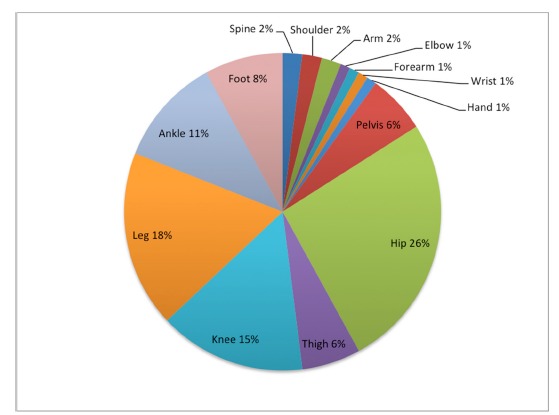

In total, 208 patients were identified with culture-positive septic arthritis and/or osteomyelitis in this seven-year period (Fig. 1). Of those, SA was identified as the causative organism in 131 patients (64%) and GABS in 21 (10%). Other organisms were identified in 52 patients (25%). Of the 126 non-ICU patients with SA, 106 had MSSA bone and joint infections and 20 had MRSA (Table 3).

Fig. 1. Sites of involvement.

Table 3. Characteristics of patients stratified by causative organisms and level of care.

| Culture negative | SA (n = 132) | GABS (n = 21) | Other (n = 55) | Total (n = 208) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSSA (n = 107) | MRSA (n = 25) | SA total (n = 132) | |||||

| Non-ICU care | 223 | 106 | 20 | 126 | 14 | 52 | 415 |

| ICU care | 0 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 3* | 16 |

| TSS/STSS | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 | n/a | 6 | |

three patients treated in the ICU for meningitis due to Neisseria meningitidis underwent surgery for secondary bone and joint infections after initial treatment of their meningitis

ICU, intensive care unit; TSS, toxic shock syndrome; STSS, streptococcal TSS; SA, Staphylococcus aureus; MSSA, methicillin-sensitive SA; MRSA, methicillin-resistant SA; GABS, Group A β-haemolytic Streptococcus pyogenes

Overall, 16 of 208 patients (8%) with culture-positive bone and joint infections were treated in the ICU for critical illness, 6/131 (5%) with SA and 7/21 (33%) with GABS. Of these 13 patients, there were seven female and six male patients with a mean age of nine years. A significantly higher proportion of those with MRSA (5/25 patients or 20%) were admitted to the ICU for critical illness than those with MSSA (1/106 or < 1%) (p = 0.0009). Overall, GABS patients had a statistically greater likelihood of admission to the ICU than those patients with SA bone and joint infections (odds ratio 10.55, 95% confidence interval 3.093 to 35.65, p = 0.0002), though patients with MRSA infections were just as likely to need ICU care (6/26) as patients with GABS infections (7/21) (p = 0.8). Length of hospital and ICU stays, number of surgeries and re-admission rates were similar for the MRSA and GABS ICU patients (Table 4). None of the ICU patients had an underlying syndrome or immune-compromised state predisposing them to severe infection.

Table 4. Characteristics of intensive care unit (ICU) patients with Staphylococcus aureus (SA) and Group A β-haemolytic Streptococcus pyogenes (GABS).

| ICU data, mean (sd) | SA | GABS (n = 7) | p-value* | Overall (n = 13) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSSA (n = 1) | MRSA (n = 5) | Total (n = 6) | ||||

| Surgeries (n) | 0 | 5 (4) | 4 (4) | 3 (2) | 0.3 | 3 (3) |

| Procedures (n) | 0 | 14 (12) | 12 (12) | 10 (7) | 0.4 | 10 (9) |

| Length of ICU stay (days) | 3 | 17 (11) | 14 (11) | 11 (7) | 0.4 | 12 (9) |

| Length of stay (days) | 4 | 31 (12) | 27 (15) | 32 (23) | 0.8 | 29 (19) |

| Re-admissions (n) | 0 | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 0.3 (0.5) | 0.4 | 0.6 (1) |

comparing SA patients with GABS ICU patients

Sd, standard deviation; MSSA, methicillin-sensitive SA; MRSA, methicillin-resistant SA

Five of the seven patients in the streptococcal group met criteria for STSS, whereas only one of the patients in the staphylococcal group met criteria for TSS (p = 0.10). The two patients in the GABS group who did not meet requirements for a diagnosis of STSS also had episodes of severe hypotension requiring inotropic/vasopressor support. No patient with TSS died. As our institution is a tertiary referral centre, many patients with bone and joint infections (1/14 non-ICU patients with GABS and 17/120 non-ICU patients with SA), and most of those also with critical illness (7/8 with GABS and 5/6 with SA), were transferred after initial workup at outside hospitals. Patients ultimately requiring ICU care typically presented with sudden worsening of myalgias and arthralgias, nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain, one or more joints with particular irritability, hypotension and respiratory distress, a markedly elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) (> 15 mg/dL in all cases) and rapidly positive blood culture, though 5/13 had no obvious symptoms of bone or joint involvement when admitted to the ICU for critical illness.

Discussion

Although SA more commonly causes osteomyelitis and septic arthritis in children, we found a higher proportion of patients affected with GABS meeting criteria for TSS and requiring ICU hospitalisation for this potentially life-threatening condition. Breaking down SA into MRSA and MSSA, those with MRSA bone and joint infections were significantly more likely to require ICU care than those with MSSA, although the rates of ICU admission for MRSA and GABS were equivalent. Of those admitted to the ICU, there were no significant differences in days hospitalised, number of trips to the operating room or number of re-hospitalisations when comparing MRSA patients with GABS patients.

There are few published reports on GABS and bone and joint infections in children. Ibia et al17 described 29 paediatric patients with GABS but did not describe critical illness in any of these patients. Givner et al16 reported on 17 children with GABS infections and sepsis, four of whom had soft-tissue, bone or joint involvement.16 Christie et al15 reported on 60 children with GABS bacteraemia, 17 of whom were diagnosed with osteomyelitis and septic arthritis. The mortality rate in that series was 7% overall. In addition, despite prior reports of mortality as high as 80% in patients with STSS,25 there were no deaths in the six patients with TSS in our study. It is unclear whether this low incidence was due to prompt recognition, early treatment and aggressive care or the small study group.

While other authors have commented upon the epidemiology of invasive GABS infections noting increased recognition and reporting of these critically ill patients,26 the small number of cases in this series limits our ability to comment on an increase or change in incidence of the disease. Nonetheless, GABS infections typically led to prolonged ICU stays, intubation, hypotension and coagulopathy, with multiple operating room trips and long-term antibiotic treatment. Unlike previous reports from this institution and others,4,10,27,28 these infections were not preceded by recent varicella infections.

Though only one of six ICU patients with SA met the criteria for TSS, they were all critically ill, suffering septic shock with multi-organ involvement. Sepsis associated with MRSA infection has been described by others29,30 and the frequency of serious bone and joint infection from MRSA infection has been reported to be on the rise.31 Our more recent experience would support that conclusion, as the percentage of patients with SA musculoskeletal infection (septic arthritis and osteomyelitis) due to MRSA has risen, from 15% (20/131) in this study between 2002 and 2008 to 22% (8/37) for patients with septic arthritis between 2006 and 2013 reported by Telleria et al.32

This series leads us to recommend prompt evaluation and aggressive treatment of systemic symptoms in paediatric patients with GABS or MRSA septic arthritis or osteomyelitis. For those patients with systemic sepsis and symptoms of toxic shock, the signs of bone and joint infection may be masked by their critical illness. Though identification of the infectious organism often occurs after initiation of the resuscitation of a critically ill patient, a rapidly positive blood culture and a gram stain positive for gram-positive cocci in chains as well as a presenting CRP > 15 mg/dL should herald an increased likelihood for severe systemic illness. In this setting in particular, suspecting the possibility of bone and joint involvement may enable early diagnosis, increasing the effectiveness of aggressive surgical and medical treatments, potentially decreasing ICU stays and reducing the long-term musculoskeletal sequelae of infection.

This study is limited by its retrospective nature and by the small numbers of patients. Almost all of our ICU patients were transferred from outside hospitals and as such we cannot estimate the incidence of such infections.

Patients with GABS bone and joint infections are more likely to develop critical illness requiring ICU admission than those with SA, though patients with MRSA infection are just as likely as those with GABS to require ICU care. GABS septic arthritis and/or osteomyelitis increase the likelihood of TSS when compared with bone and joint infections with SA. Patients with rapidly positive blood cultures, particularly those with gram-positive cocci in chains, and a presenting CRP > 15 mg/dL are at an increased risk of developing septic shock and should be carefully monitored.

Future studies involving larger populations may provide further insight into factors that contribute to the severity of disease in patients with GABS and MRSA bone and joint infections. We urge early and aggressive resuscitation and surgical decompression of bone and joint infections in the critically ill patient to optimise the effectiveness of treatment.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Dr Viviana Bompadre for her assistance with data analysis, essential to this research.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Funding Statement

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

Ethical Statement

Ethical Approval: This study was approved by the hospital’s Institutional Review Board: IRB #11871.

Informed Consent: Not required.

References

- 1.Faden H, Grossi M. Acute osteomyelitis in children. Reassessment of etiologic agents and their clinical characteristics. Am J Dis Child 1991;145:65-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fink CW, Nelson JD. Septic arthritis and osteomyelitis in children. Clin Rheum Dis 1986;12:423-435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gillespie R. Septic arthritis in childhood. Clin Orthop 1973;96:152-159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doctor A, Harper MB, Fleisher GR. Group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal bacteremia: historical overview, changing incidence, and recent association with varicella. Pediatrics 1995;96:428-433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Green NE, Edwards K. Bone and joint infections in children. Orthop Clin North Am 1987;18:555-576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karwowska A, Davies HD, Jadavi T. Epidemiology and outcome of osteomyelitis in the era of sequential intravenous-oral therapy. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1998;17:1021-1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith T. On the acute arthritis of infants. St. Bartholomew’s Hospital Reports 1874;10:189-204. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bennett OM, Namnyak SS. Acute septic arthritis of the hip joint in infancy and childhood. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1992;281:123-132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stevens DL, Tanner MH, Winship J, et al. Severe group A streptococcal infections associated with a toxic shock-like syndrome and scarlet fever toxin A. N Eng J Med 1989;321:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davies HD, McGeer A, Schwartz B, et al. Invasive group A streptococcal infections in Ontario, Canada. N Eng J Med 1996;335:547-554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mehta S, McGreer A, Low DE, et al. Morbidity and mortality of patients with invasive group A Streptococcal infections admitted to the ICU. Chest 2006;130:1679-1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cunningham MW. Pathogenesis of group A streptoccocal infections. Clin Micro Rev 2000;13:470-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deighton C. Beta haemolytic streptococci and musculoskeletal sepsis in adults. Ann Rhem Dis 1993;52:483-487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mascini EM, Janze M, Schellekens JF, et al. Invasive group A streptococcal disease in the Netherlands: Evidence for a protective role of anti-exotoxin A antibodies. J Inf Dis 2000;181:631-638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Christie CD, Havens PL, Shapiro ED. Bacteremia with group A streptococci in childhood. Am J Dis Child 1988;142:559-561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Givner LB, Abramson JS, Wasilauskas B. Apparent increase in the incidence of invasive group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal disease in children. J Pediatr 1991;118:341-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ibia EO, Imoisili M, Pikis A. Group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal osteomyelitis in children. Pediatrics 2003;112:e22-e26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alwattar BJ, Stongwater A, Sala DA. Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome presenting as septic knee arthritis in a 5-year-old child. J Pediatr Orthop 2008;28:124-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Todd J, Fishaut M, Kapral F, Welch T. Toxic-shock syndrome associated with phage-group-I Staphylococci. Lancet 1978;2:1116-1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cone LA, Woodard DR, Schlievert PM, Tomory GS. Clinical and bacteriologic observations of a toxic shock-like syndrome due to Streptococcus pyogenes. N Engl J Med 1987;317:146-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lappin E, Ferguson AJ. Gram-positive toxic shock syndromes. Lancet Infect Dis 2009;9:281-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Breiman RF, Davis JP, Facklam RR, et al. Defining the group A streptococcal toxic shock syndrome. JAMA 1993;269:390-391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.No authors listed. CDC. Streptococcal Toxic-Shock Syndrome (STSS) Streptococcus pyogenes) 2010 Case Definition. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nndss/conditions/streptococcal-toxic-shock-syndrome/case-definition/2010/ (date last accessed 25August2017).

- 24.No authors listed. CDC. Toxic Shock Syndrome (Other than Streptococcal) (TSS) 2011 Case Definition. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nndss/conditions/toxic-shock-syndrome-other-than-streptococcal/case-definition/2011/ (date last accessed 25August2017).

- 25.Davies HD, McGeer A, Schwartz B, et al. Invasive group A streptococcal infections in Ontario, Canada. N Engl J Med 1996;335:547-554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stevens DL. The flesh-eating bacterium: what’s next? J Infect Dis 1999;179:S366-S374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mills WJ, Mosca VS, Nizet V. Orthopaedic manifestations of invasive group A streptococcal infections complicating primary varicella. J Pediatr Orthop 1996;16:522-528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tyrrell GJ, Lovgren M, Kress B, Grimsrud K. Varicella-associated invasive group A streptococcal disease in Alberta, Canada--2000-2002. Clin Infect Dis 2005;40:1055-1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee CY, Lee YS, Tsao PC, Jeng MJ, Soong WJ. Musculoskeletal sepsis associated with deep vein thrombosis in a child. Pediatr Neonatol 2016;57:244-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shime N, Kawasaki T, Saito O, et al. Incidence and risk factors for mortality in paediatric severe sepsis: results from the national paediatric intensive care registry in Japan. Intensive Care Med 2012;38:1191-1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sarkissian EJ, Gans I, Gunderson MA, et al. Community-acquired Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus Musculoskeletal Infections: Emerging Trends Over the Past Decade. J Pediatr Orthop 2016;36:323-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Telleria JJ, Cotter RA, Bompadre V, Steinman SE. Laboratory predictors for risk of revision surgery in pediatric septic arthritis. J Child Orthop 2016;10:247-254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]