Abstract

Background & objectives:

Differential diagnosis of Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever (CCHF) from other acute febrile illnesses with haemorrhagic manifestation is challenging in India. Nosocomial infection is a significant mode of transmission due to exposure of healthcare workers to blood and body fluids of infected patients. Being a risk group 4 virus, laboratory confirmation of infection is not widely available. In such a situation, early identification of potential CCHF patients would be useful in limiting the spread of the disease. The objective of this study was to retrospectively analyse clinical and laboratory findings of CCHF patients that might be useful in early detection of a CCHF case in limited resource settings.

Methods:

Retrospective analysis of clinical and laboratory data of patients suspected to have CCHF referred for diagnosis from Gujarat and Rajasthan States of India (2014-2015) was done. Samples were tested using CCHF-specific real time reverse transcription (RT)-PCR and IgM ELISA.

Results:

Among the 69 patients referred, 21 were laboratory confirmed CCHF cases of whom nine had a history of occupational exposure. No clustering of cases was noted. Platelet count cut-off for detection of positive cases by receiver operating characteristic curve was 21.5×10[9]/l with sensitivity 82.4 per cent and specificity 82.1 per cent. Melaena was a significant clinical presentation in confirmed positive CCHF patients.

Interpretation & conclusions:

The study findings suggest that in endemic areas thrombocytopenia and melaena may be early indicators of CCHF. Further studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Key words: Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever, diagnosis, Gujarat, haemorrhage, India, melaena, platelet, suspected case

Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever (CCHF) is a life-threatening viral haemorrhagic fever1, endemic in several countries across Africa, Asia, Eastern Europe and the Middle East2. The existence of CCHF in India was first documented during a nosocomial outbreak in Gujarat in 20113. However, a cross-sectional serosurvey of CCHF among livestock in 22 States in India during 2013-2014 has suggested countrywide existence of antibody against this pathogen among animals4. Clinical presentation of CCHF is variable, ranging from mild non-specific febrile illness to multi-organ failure, shock and haemorrhage. In India, this disease needs to be differentiated from other infections such as dengue, leptospirosis, rickettsiosis, brucellosis, Q fever and other haemorrhagic fevers5,6,7. Secondary infection commonly occurs due to human-to-human transmission through percutaneous/mucosal exposure to blood and body fluids containing the virus. This transmission takes place most often among healthcare workers in hospital settings, thus posing a significant nosocomial hazard2. Early identification and isolation of suspected CCHF patients is, therefore, important, so that preventive measures and precautions could be taken to limit the spread of disease.

Since CCHF virus is a biosafety level 4 pathogen testing is usually performed at referral laboratories and this process takes time to transport the specimen and getting the result. This increases the time of contact with other people and thus the risk of causing secondary infection, if suspected cases are not isolated immediately. Criteria previously established for CCHF are predictors of severity in identified cases and include an array of laboratory findings which may not be readily available in a resource-limited endemic setting. In this study an attempt has been made to identify predictors of CCHF, from clinical and commonly available laboratory tests, in endemic areas. This will help in early identification of suspected cases and timely adoption of prevention and control strategies to limit the spread of infection.

Material & Methods

Retrospective analysis of clinical and laboratory data of patients suspected to have CCHF referred from different locations of Gujarat and Rajasthan States of India was carried out. Data were recorded on a standard proforma provided by National Institute of Virology (NIV), Pune. Information on patients suspected to have CCHF whose samples were negative for Dengue NS1 and IgM ELISA were referred between January 2014 and September 2015, was analyzed. A suspected patient is defined as an individual with abrupt onset of high fever >38.5°C with one of the following symptoms: severe headache, myalgia, nausea, vomiting and/or diarrhoea with a history of tick bite within 14 days before the onset of symptoms; or history of contact with tissues, blood or other biological fluids from a possibly infected animal within 14 days prior the onset of symptoms; or healthcare workers in healthcare facilities, with a history of exposure to a suspect, probable or laboratory-confirmed CCHF patient, within 14 days before the onset of symptoms. Probable CCHF patient is defined as a suspected CCHF patient fulfilling, in addition, the following criteria: thrombocytopenia <50,000/μl and two of the following haemorrhagic manifestations: haematoma at an injection site, petechiae, purpuric rash, rhinorrhagia, haematemesis, haemoptysis, gastrointestinal (GI) haemorrhage, gingival haemorrhage or any other haemorrhagic manifestation in the absence of any known precipitating factor for haemorrhagic manifestation. A confirmed CCHF patient is one who is laboratory-confirmed8. Samples were tested at the Maximum Containment laboratory at NIV, Pune, using CCHF virus-specific real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and IgM ELISA. In addition, anti-CCHF IgM antibodies were also screened for all the samples9. Approval for the study was obtained from Institutional Human Ethics Committee, NIV, Pune.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis was performed for the studied variables. Proportion comparisons for categorical variables were performed using Chi-square tests. Mean comparisons for continuous variables were performed using independent group t test and Mann–Whitney test. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used for determination of cut-off values. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was carried out on significant univariate predictors using forwards stepwise procedure.

Results

During the study period, samples from 69 clinically suspected cases of CCHF were referred for diagnosis to NIV, Pune. Twenty one (30.4%) were confirmed by laboratory testing. Nine of these 21 patients had a history of occupational exposure (shepherd, farmer and staff nurse). Demographics of confirmed patients showed that they were referred to tertiary care centres in several locations across Gujarat State. Only sporadic cases were observed. Average time to diagnosis of confirmed cases was 6±2.8 days including transport time. The majority of laboratory-confirmed CCHF patients were recorded among adult males (16/21). Mean age of CCHF confirmed patients was 38±10 yr, which was significantly higher than those who tested negative for CCHF (P<0.01). Case fatality rate of 33 per cent (7/21) was noted. Three nursing staffs who came in contact with a fatal case of CCHF developed the disease, of whom one died.

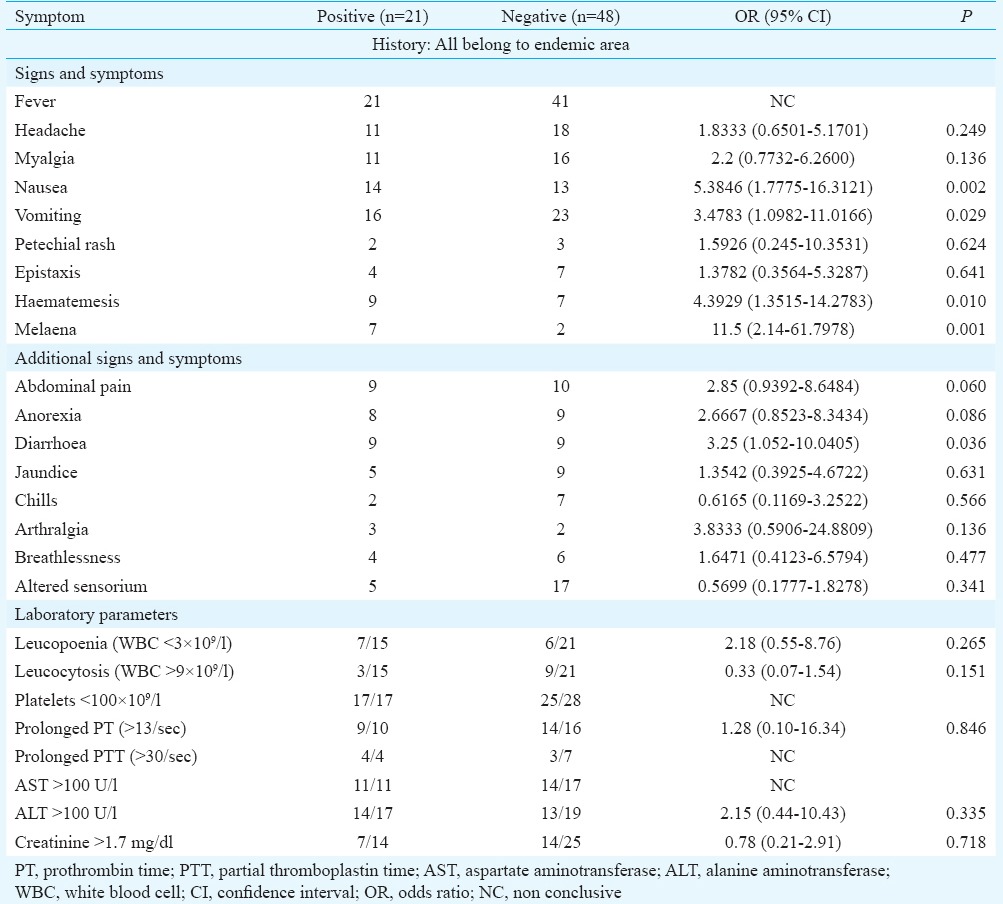

All suspected patients presented with fever. Headache and myalgia were observed in more than half of the patients. GI symptoms including nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea were significantly associated with CCHF positivity (Table I). Haemorrhage was observed from different sites including GI, mucosal and cutaneous. Site of first bleeding was variable. Haemorrhage was also noted in all fatal cases. The occurrence of haematemesis (P=0.01) and melaena (P<0.001) was significant, whereas cutaneous haemorrhage was not significant (Table I). Multivariable logistic regression was carried out on platelet counts (logarithmic transformation was used), melaena, haematemesis, nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea. Among these six predictors, three were significant. Adjusted odds ratio for platelet count was 0.05 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.006-0.412], melaena was 14.6 (95% CI 1.3-163.5) and for nausea 9.1 (95% CI 1.3-64.2), indicating an independent association of these predictors with CCHF positive cases. The fitted model Nagelkerke R2 was 54.7 per cent. Respiratory symptoms were uncommon. Neurological complications (5/21) were noted only among fatal cases.

Table I.

Clinical history and laboratory findings in Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever positive and negative patients

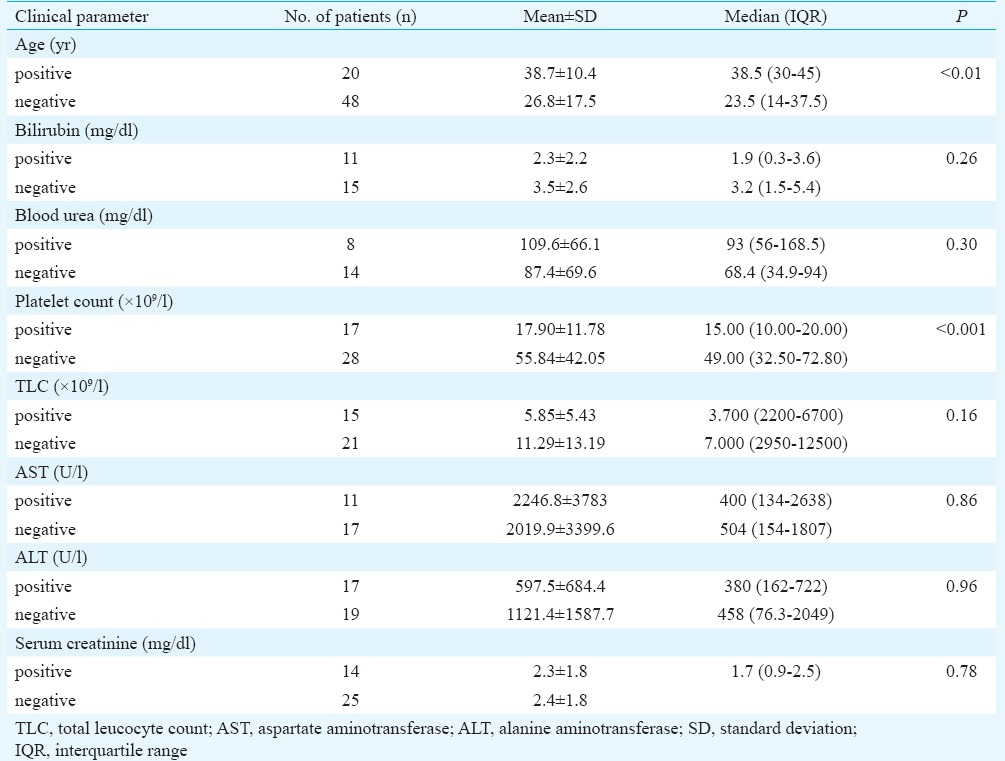

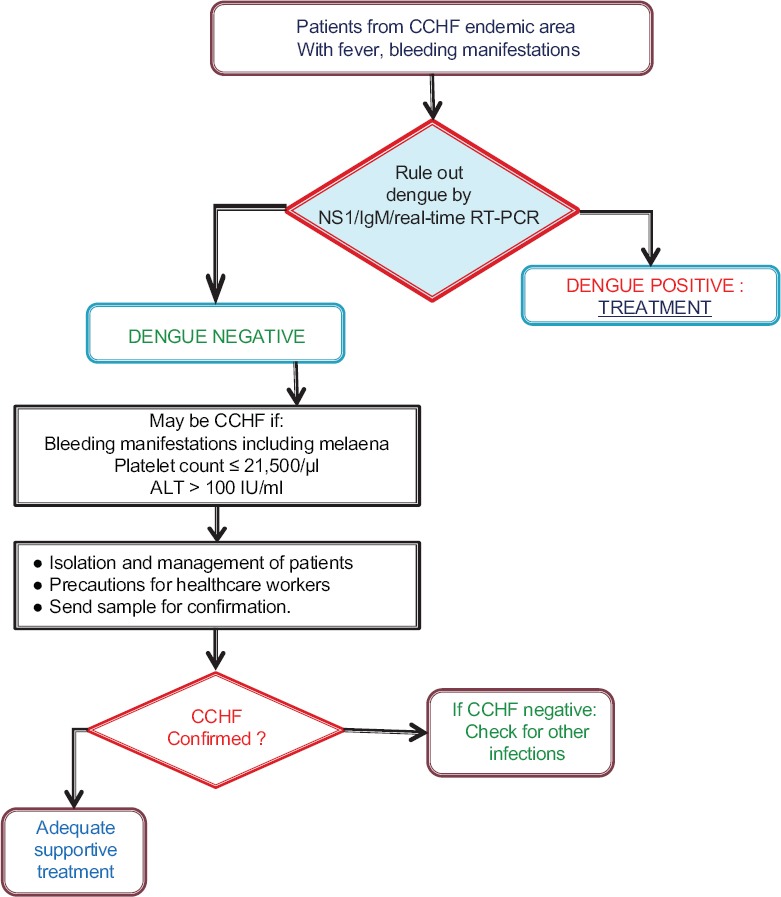

Among the laboratory findings of CCHF confirmed cases, the most significant finding was thrombocytopenia, with platelet count <100,000/μl noted in all cases. The mean platelet count (17.9×109/l) of CCHF confirmed patients was also significantly reduced (P<0.001). ROC curve gave area under curve 0.83 (95% CI 0.70-0.95) (Table I). The cut-off value (ROC curve) for platelet count of 21.5×109/l had sensitivity of 82.4 per cent and specificity of 82.1 per cent. Using a cut-off of 100 U/l, higher alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels were noted (14/17). Mean leucocyte count of positive cases was below normal (5.9×109/l) as compared to CCHF negative patients (11.3×109/l) (Table II). Although blood urea and creatinine levels were raised, these were not significant and only one case of renal failure occurred. Based on our results, decision tree for identification of suspected CCHF was drawn (Figure).

Table II.

Laboratory investigations of Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever positive and negative patients

Figure.

Decision tree for diagnosis of Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever (CCHF). ALT, alanine aminotransferase.

Discussion

The wide geographical distribution of the vector, Hyalomma spp. tick has made CCHF virus the second most widespread of all medically important arboviruses, after dengue virus10,11. The variable clinical spectrum of disease makes it difficult to identify CCHF in countries where tropical febrile illnesses commonly occur. Previously, awareness in India about this disease was minimal. However, after a nosocomial outbreak in Gujarat in 20113, it was recognized that CCHF could also be a cause of febrile infection and viral hemorrhagic fever.

In the present study, an attempt was made to understand whether history, clinical features and routine haematology and biochemical findings could provide a clue to identify suspected cases of CCHF in endemic areas. Although CCHF patients commonly present with fever, headache, myalgia and fatigue11, nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea are also noted12,13. These GI manifestations were found to be of significant in our study. Although nausea was independently associated with cases, it is a non-specific finding and may occur in many infections. Even though CI for melaena was wide, it emerged as an important factor for identification of patients.

Several criteria12,14,15,16,17 have been devised for CCHF. However, most of these are designed as predictors of severity in identified cases and include an array of laboratory findings. All these tests may not be readily available in a resource-limited endemic setting. It is essential to evolve a simple method to identify suspected cases of CCHF in such settings. We, therefore, concentrated on a few haematological and biochemical tests, as these investigations are usually available even at peripheral centres and could, therefore, provide a quick clue to the diagnosis of CCHF. The minimum investigations to be performed would be complete haemogram and liver function tests. Platelet counts less than 21.5×109/l, ALT >100 U/l and leucopenia or low normal leucocyte count could be suggestive of CCHF. Such patients would need to be referred for confirmatory testing.

Our laboratory data showed persistence of viral RNA in urine even on day 12 of illness18. Such patients can spread the disease rapidly to fellow patients or attending healthcare workers. This underlines the need for early identification of potential cases of CCHF.

It is important to differentiate CCHF from other tropical febrile illnesses such as dengue, leptospirosis and malaria. Available literature suggests that although leptospirosis is associated with thrombocytopenia, leucocyte counts are normal or raised and neutrophilia is documented19. Clinical picture is also different with pulmonary and renal involvement.

Severe haemorrhage is seen in five per cent of severe malaria patients20. A study from Pakistan21 showed that up to 12 per cent of malaria patients might have platelet counts between 25 and 50×109/l. However, count below 20×109/l as observed in our study was not usually found.

Dengue fever is an important differential diagnosis of CCHF as it is also associated with leucopenia, thrombocytopenia and raised ALT22,23,24. Early clinical presentation of dengue fever and CCHF may be similar, characterized by headache, myalgia and nausea and vomiting22. Although thrombocytopenia is documented, mean platelet count is not usually below 50×109/l. Leucopenia and raised ALT are observed, but ALT >100 U/l is uncommon.

In severe dengue [dengue haemorrhagic fever (DHF)], low platelet counts, even below 20×109/l are documented along with ALT >100 U/l25. Such cases may be difficult to distinguish from CCHF. Cutaneous haemorrhage was found to be more common in DHF22,23, in contrast to our study where it was not a significant finding. Further, testing for dengue is usually available at most centres and the disease can be quickly ruled out or confirmed by NS1 antigen or IgM detection.

The key to management of CCHF is prompt and adequate supportive treatment. Although ribavirin is increasingly being used, yet there are no definitive data on the efficacy of antiviral therapy for CCHF9,26,27.

Our study had some limitations. Viral load, which can be an independent predictor of mortality, was not studied. The small sample size was another limitation. The complete data for all the patients could not be traced. History of exposure or tick bite was also difficult to document.

In conclusion, our findings show that haemorrhagic manifestations including melaena, low platelet count and raised ALT may provide a clue to early suspicion of CCHF in areas known to have this infection, before the availability of confirmatory diagnosis. Further studies are necessary to substantiate these findings.

Acknowledgment

Authors acknowledge the contribution of staff of Maximum Containment Laboratory, NIV, Pune, for conducting the laboratory tests and providing results and Shri A. M. Walimbe for supporting advanced statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- 1.Bente DA, Forrester NL, Watts DM, McAuley AJ, Whitehouse CA, Bray M. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever: History, epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical syndrome and genetic diversity. Antiviral Res. 2013;100:159–89. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Appannanavar SB, Mishra B. An update on Crimean Congo hemorrhagic Fever. J Glob Infect Dis. 2011;3:285–92. doi: 10.4103/0974-777X.83537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mishra AC, Mehta M, Mourya DT, Gandhi S. Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever in India. Lancet. 2011;378:372. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60680-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mourya DT, Yadav PD, Shete AM, Sathe PS, Sarkale PC, Pattnaik B, et al. Cross-sectional serosurvey of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus IgG in livestock, India, 2013-2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:1837–9. doi: 10.3201/eid2110.141961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marczinke BI, Nichol ST. Nairobi sheep disease virus, an important tick-borne pathogen of sheep and goats in Africa, is also present in Asia. Virology. 2002;303:146–51. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whitehouse CA. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever. Antiviral Res. 2004;64:145–60. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mourya DT, Yadav PD, Mehla R, Barde PV, Yergolkar PN, Kumar SR, et al. Diagnosis of kyasanur forest disease by nested RT-PCR, real-time RT-PCR and IgM capture ELISA. J Virol Methods. 2012;186:49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2012.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maltezou HC, Papa A, Tsiodras S, Dalla V, Maltezos E, Antoniadis A. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in Greece: A public health perspective. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13:713–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2008.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mourya DT, Yadav PD, Shete AM, Gurav YK, Raut CG, Jadi RS, et al. Detection, isolation and confirmation of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus in human, ticks and animals in Ahmadabad, India, 2010-2011. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1653. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watts DM, Ksiazeck TG, Linthicum KJ, Hoogstraal H. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever. In: Monath TP, editor. The arboviruses: Epidemiology and ecology. Florida: CRC Press; 1988. pp. 177–222. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ergönül O. Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:203–14. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70435-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ozturk B, Tutuncu E, Kuscu F, Gurbuz Y, Sencan I, Tuzun H. Evaluation of factors predictive of the prognosis in Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever: New suggestions. Int J Infect Dis. 2012;16:e89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mardani M, Keshtkar-Jahromi M. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever. Arch Iran Med. 2007;10:204–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swanepoel R, Shepherd AJ, Leman PA, Shepherd SP, McGillivray GM, Erasmus MJ, et al. Epidemiologic and clinical features of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in southern Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1987;36:120–32. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1987.36.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bakir M, Ugurlu M, Dokuzoguz B, Bodur H, Tasyaran MA, Vahaboglu H. Turkish CCHF Study Group. Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever outbreak in middle Anatolia: A multicentre study of clinical features and outcome measures. J Med Microbiol. 2005;54(Pt 4):385–9. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.45865-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ergonul O, Celikbas A, Baykam N, Eren S, Dokuzoguz B. Analysis of risk-factors among patients with Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever virus infection: Severity criteria revisited. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006;12:551–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leblebicioglu H, Ozaras R, Irmak H, Sencan I. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in Turkey: Current status and future challenges. Antiviral Res. 2016;126:21–34. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Makwana D, Yadav PD, Kelaiya A, Mourya DT. First confirmed case of Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever from Sirohi district in Rajasthan State, India. Indian J Med Res. 2015;142:489–91. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.169221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Silva NL, Niloofa M, Fernando N, Karunanayake L, Rodrigo C, De Silva HJ, et al. Changes in full blood count parameters in leptospirosis: A prospective study. Int Arch Med. 2014;7:31. doi: 10.1186/1755-7682-7-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patel DP, Pradeep P, Surti MM, Agarwal SB. Clinical manifestations of complicated malaria – An overview. J Indian Acad Clin Med. 2003;4:323–31. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khan SJ, Abbass Y, Marwat MA. Thrombocytopenia as an indicator of malaria in adult population. Malaria Res Treat. 2012;2012:405981. doi: 10.1155/2012/405981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ho TS, Wang SM, Lin YS, Liu CC. Clinical and laboratory predictive markers for acute dengue infection. J Biomed Sci. 2013;20:75. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-20-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malavige GN, Velathanthiri VGNS, Wijewickrama ES, Fernando S, Jayaratne SD, Aaskov J, et al. Patterns of disease among adults hospitalized with dengue infections. QJM. 2006;99:299–305. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcl039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guilarde AO, Turchi MD, Siqueira JB, Jr, Feres VC, Rocha B, Levi JE, et al. Dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever among adults: Clinical outcomes related to viremia, serotypes, and antibody response. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:817–24. doi: 10.1086/528805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bhaskar E, Sowmya G, Moorthy S, Sundar V. Prevalence, patterns, and factors associated with bleeding tendencies in dengue. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2015;9:105–10. doi: 10.3855/jidc.5031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ascioglu S, Leblebicioglu H, Vahaboglu H, Chan KA. Ribavirin for patients with Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:1215–22. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soares-Weiser K, Thomas S, Thomson G, Garner P. Ribavirin for Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:207. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]