Abstract

With the advent of newer imaging modalities retained surgical items are now easily diagnosed by their characteristic imaging appearances. A combination of complementary imaging modalities helps to arrive at the diagnosis of this relatively rare complication. Factors contributing to their imaging features include the timing of diagnosis and imaging, presence of secondary infection, communication of the retained item with hollow viscus or external skin wound, and type of imaging modality used. A high index of suspicion is necessary for diagnosis before labeling it as a retained surgical item. In parallel with recent advances in surgery, it is essential that there is increasing awareness among radiologists regarding the newer types of retained surgical items.

Keywords: Calcified, computed tomography, differential diagnosis, gossypiboma, imaging, magnetic resonance imaging, PET CT, retained surgical items, USG

Introduction

The term gossypiboma is derived from the Latin word “gossypium” meaning cotton wool, the suffix -oma meaning mass. Some authors also suggest that the latter part comes from the Swahili word “boma” which means concealment;[1] the reference to the source is not clarified. Other terms used are “textiloma,” “gauzoma,” “muslinoma.” A suitable example of a gossypiboma would be a mass-like reaction to surgical sponges that are accidentally left inside the patient during surgery. With the introduction of a newer and broader term “retained surgical items” (RSI), additional materials such as needles, broken instruments, irrigation sets, and rubber materials have been included in the conventional list.[2]

ICD-10 (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems) classifies retained foreign bodies/objects and related complications in blocks from T81.5 to T81.6.[3]

The incidence of RSI is difficult to estimate as patients may be asymptomatic as well as due to under-reporting of cases. The reported incidence varies between 1 per 1000 and 1 per 3000 procedures.[4] The wide variation in the incidence depends on the type of procedure, experience of the surgeon and operation theatre personnel, hospital policies, frequency of reporting of adverse incidences, among other factors. Even though it is impossible to eliminate the factor of human error completely, the incidence of this rare but serious complication can be significantly reduced by following the recommended perioperative guidelines and checklists.[5] There are very few reported publications on gossypiboma/RSI due to medicolegal implications. Awareness among surgeons and radiologists can lead to early diagnosis and intervention, thus preventing further complications. In this article, different imaging appearances of gossypiboma/RSI are presented including examples of newer RSI.

Pathophysiology

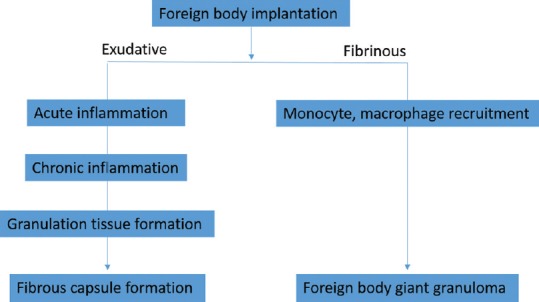

Any foreign body elicits a reaction in the human body. If the foreign body harbors microorganisms, it can introduce infection. The foreign body can also get secondarily infected. The type of reaction elicited depends on antigenicity (depending on the content of the retained item) and the presence of secondary infection. Two reactions classically described with RSI are exudative and fibrinous. The schematic flow chart of natural history of gossypibomas is showing in Figure 1.[6,7] The exudative inflammatory reaction presents early, with or without secondary infection. Once the exudative reaction is initiated, it progresses with cytokine and white blood cell interactions, acute and chronic inflammation, and end-stage fibrous capsule development.[7] The second reaction is fibrotic/fibrinous, which is characterized by a foreign body granuloma, adhesions, and encapsulation. Between the two reactions, the exudative reaction presents early with symptoms, facilitating early detection and surgical removal.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of natural history of gossypibomas

Natural history of RSI, depends on either of the above reactions, with some cases presenting in the early postoperative period. Some patients may be asymptomatic for a long time. In a few cases, retained sponges may erode the walls of viscera and migrate into the intestinal lumen due to pressure necrosis and granuloma formation and may be further propelled by peristalsis.[8] Several reported cases of spontaneous transmural migration of gossypibomas and expulsion by defecations have been published.[9]

Clinical Presentations

Surgical items can be accidentally left after any type of surgical procedure, with the most common site being abdomen and pelvis.[10,11,12,13] Other sites include skull, neck, thorax, breast, axilla, vagina, and paraspinal region. Clinical presentation depends on the site of gossypiboma/RSI and the time of presentation. Clinical presentation of abdominal gossypiboma/RSI varies from asymptomatic to emergency presentation usually in the form of abdominal pain. In acute manifestations, the patient usually presents with nonspecific abdominal pain, fever, vague abdominal lump, nausea, vomiting, abdominal wound discharge, or sepsis.[10]

Patients can also present with complications arising from gossypiboma such as intestinal obstruction, perforation, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, peritonitis, or septic shock.[8]

Subacute to chronic presentation includes vague chronic pain, anorexia, weight loss, or an abdominal mass, which can be misdiagnosed as a malignant tumor. Gossypibomas of other sites such as intrathoracic cavity, paraspinal area, cranium, breast, and neck present as symptoms related to location – chronic cough, back pain, mass effect, and discharging sinus. Sometimes gossypiboma/RSI may be unnoticed for years and are detected incidentally on imaging studies.

Risk Factors

Failure to adhere to AORN (Association of perioperative registered nurses) guidelines in counting the swabs and surgical items in open surgeries is one of the risk factors, not exclusive for RSI.[14]

Studies have indicated that females are more prone to the adverse event of retained surgical items.[15] RSI is more frequent with emergency surgeries due to sudden deviations in the plan of surgery or improper swab count. Higher body mass index is also believed to be a contributing factor due to increased technical difficulty, increased stress to the surgeon, and increased surgically exposed area.[16] A recent meta-analysis published in 2014 challenged the contribution of the abovementioned factors to increased incidence by showing no significant statistical difference in incidence with changes in nursing staff, emergency surgery, body mass index, and operation “after hours.”[17]

Imaging Features

Imaging features depend on the time since surgery, the presence of secondary infection, communication of the gossypiboma with hollow viscus or external skin wound, and the modality of the radiological investigation. A high index of suspicion is needed for diagnosing RSI. Image-guided biopsy or surgical or endoscopic retrieval are confirmatory for retained surgical gauze.[18]

Radiography

Radiographs are the most commonly used modality to detect gossypibomas.[19,20] Abdominal radiographs are commonly done postoperatively in patients with pain and abdominal symptoms. Common appearance of retained surgical gauge includes fine linear radio-opacity and associated mottled air or mass effect or density over adjacent soft tissues [Figures 2–4].[21] The radiopaque marker thread may not always be present as it may slip off or get distorted, twisted, or disintegrated over time.[22] The diagnosis is, however, difficult using only plain radiographs.[23,24,25] Radiographs can also detect complications such as concurrent intestinal obstruction or perforation.[21] In the presence of a fistula, a contrast study may reveal the location and extent.[26] Other metallic surgical items can be easily identified by their density and shape.

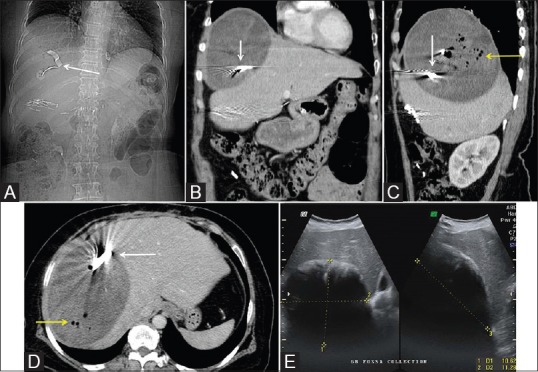

Figure 2 (A-E).

Gossypiboma of the abdomen. (A) CT topogram showing a linear hyperdense structure in right hypochondrium. (B-D) coronal, sagittal and axial images of contrast-enhanced CT showing large subphrenic fluid collection with mottled air (yellow arrow head) and a hyperdense structure giving streak artifacts (white arrows). (E) On Ultrasonography, the fluid collection showing echogenic anterior strip with posterior acoustic shadowing

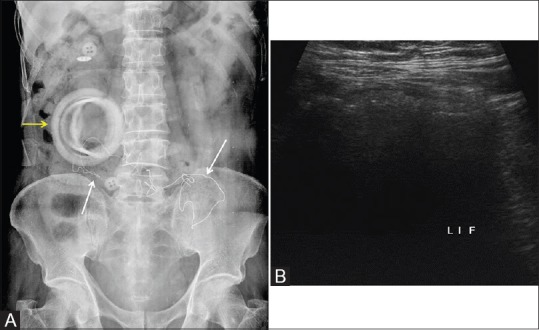

Figure 4 (A and B).

(A) Post colectomy abdomen radiograph showing few linear structures in the lower abdomen (white arrows). Ring shadow of the ileostomy bag is shown by the yellow arrow. (B) Targeted Ultrasonography showing an ill-defined mass with non-dependant air foci (arrowheads). Continued in figure 5

Computed tomography

Computed tomography (CT) is a sensitive method for detecting gossypibomas/RSI and is the next imaging modality of choice if radiographs are negative.[27] The typical imaging appearance in CT is a spongiform pattern with a radiodense linear structure [Figures 2, 3, 5 and 6]]. Peripheral rind of calcification around a reticular mass, as a characteristic feature of gossypiboma, was described in a report by Lu et al.[28] They found that the “calcified reticulate rind” sign was helpful in identifying the retained gauze piece in chronic cases where the gas bubbles within are gradually absorbed. Another characteristic appearance described is of an inhomogeneous, low-density mass with a thin high-density capsule showing marked enhancement in postcontrast studies.

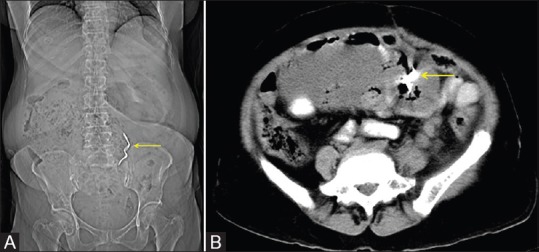

Figure 3 (A and B).

A case of carcinoma ovary, post-operative abdominal radiograph showing a linear hyperdense structure in the lower abdomen (A). The axial sections of the CT showing poorly defined fluid collection between bowel loops and a hyperdense structure within (B)

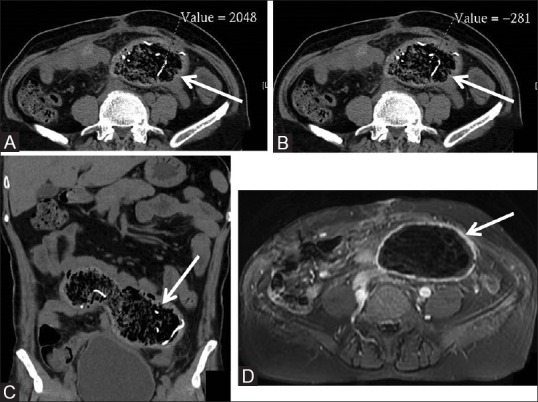

Figure 5 (A-D).

(Continued from Figure 5). (A-C) The axial and coronal CT scan images showing areas of mottled air surrounded by thick walls. The HU values of internal contents are ranging from -281 to 2048 suggestive of a combination of gauze material, fluid, and air. (D) Contrast-enhanced MRI showing central region of hypointensity with smooth enhancing walls

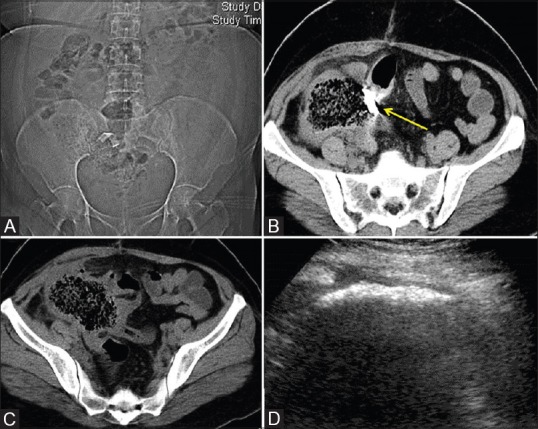

Figure 6 (A-D).

Pelvic gossypiboma. CT topogram showing a linear radiodense structure. The axial CT scan images showing the classical appearance of spongiform pattern with thick walls (C). The hyperdense structure causing minimal streak artifacts is seen within the 'wall' of the gossypiboma (B- yellow arrow). The corresponding ultrasonography image is showing an ill-defined cystic structure with an echogenic anterior strip and post acoustic shadowing (D)

Intrathoracic retained surgical swabs demonstrate well-defined smoothly contoured mass showing peripheral enhancement. As with intra-abdominal gossypiboma, central areas can be heterogeneous due to gas, calcification, and radiopaque markers.[29] Resorption of gas over time is usually seen with gossypibomas in the pleural cavity. Eventually, these appear as pleural-based masses showing atypical calcifications, with the thick, irregular inflammatory walls mimicking chronic infections, granulomatous processes, or neoplasms.[29,30]

Small metallic or metal containing RSI can be readily identified and are demonstrated better with maximum intensity projections (MIP) [Figures 7 and 8].

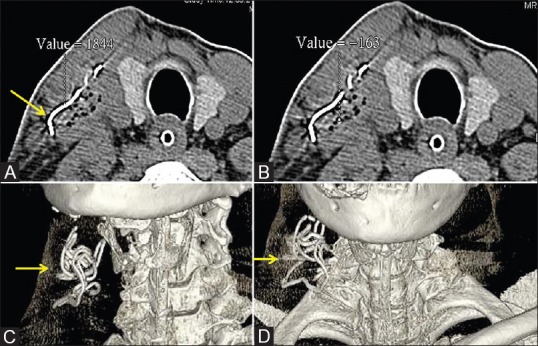

Figure 7 (A-D).

A case of retained surgical swab in the neck. (A and B) axial CT scan images showing heterogeneous area with air densities and a linear high density representing the radiodense marker of gauze. (Figure A) The HU value of the radiodense material is 1844 and (Figure B) the HU value of the mottled dark area is -163; higher than expected HU value of air (-1000) due to partial volume effect. (C and D) Shaded surface display showing whorled coil of the radiodense marker

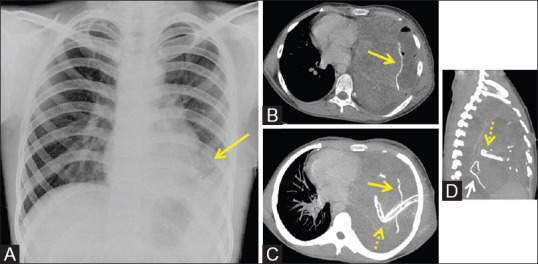

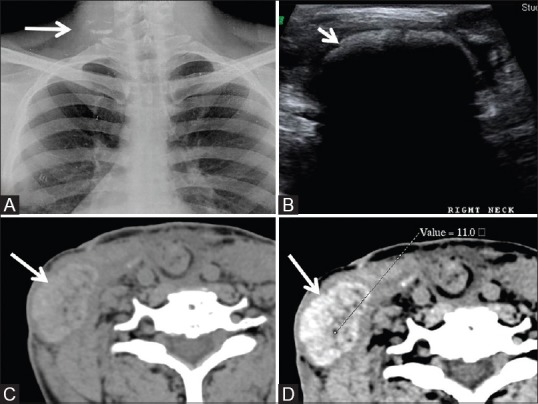

Figure 8 (A-D).

Intrathoracic retained surgical gauze. (A) Frontal chest radiograph showing an ill-defined opacity in left lower zone. After several days, the patient underwent chest CT scan for increased symptoms. (B) Axial images of CT scan showing a linear radiodensity within the area of consolidation. (C and D) MIP images in axial and sagittal reformation. (yellow arrows are showing the hyperdense material of the surgical gauze and the dotted yellow arrows are showing the intercostal drainage tube)

Ultrasonography

The sonographic imaging appearances of retained sponge/gauge are classified as three types [Figures 2, 4, 6, 9A–C and 10].[31]

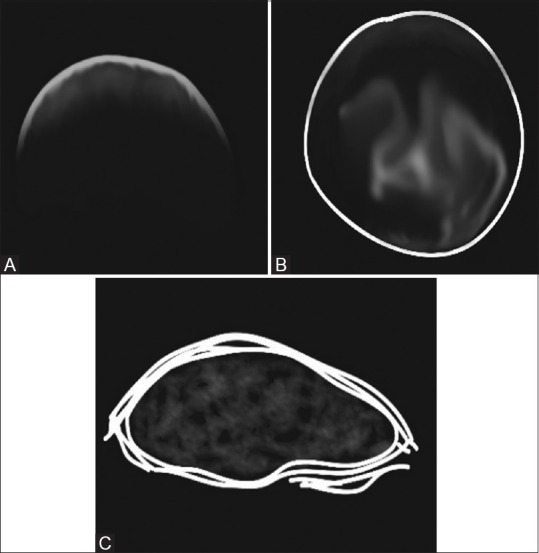

Figure 9 (A-C).

Illustrative diagrams showing the different appearances of gossypiboma on sonography. (A) Poorly defined echogenic area/echogenic anterior strip with intense posterior acoustic shadowing, (B) A well-circumscribed cystic mass containing internal mottled contents. (C) Non-specific pattern stimulating a complex mass. The posterior acoustic pattern is a consistent finding due to a combination of gauze material, air foci, and calcified regions

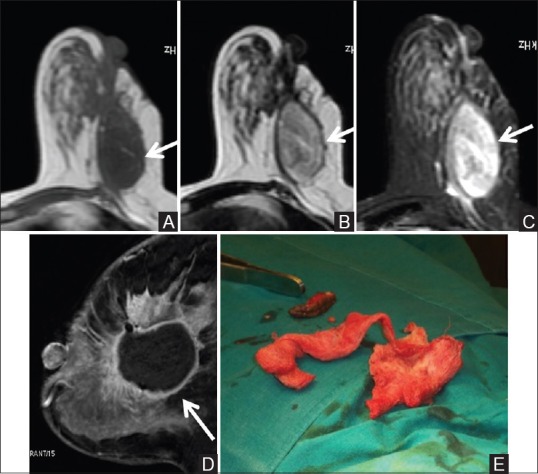

Figure 10 (A-D).

Another case of retained surgical swab in the lower neck, post neck dissection. (A) Radiograph showing irregular linear and specks of densities (white arrow). (B) Sonography image showing cavity showing highly reflective contents with posterior acoustic shadowing. (C and D) Plain and contrast-enhanced axial CT scan images show hyperdense well-defined mass showing intense but heterogeneous contrast enhancement. The central area shows negative HU due to the presence of gas. Note non-visualization of the radiodense marker

Poorly defined echogenic area/echogenic anterior strip with intense posterior acoustic shadowing,

A well-circumscribed cystic mass containing internal mottled contents,

Nonspecific pattern stimulating a complex mass. The posterior acoustic pattern is a consistent finding due to a combination of gauze material, air foci, and calcified regions.

Magnetic resonance imaging

On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), a combination of cotton, water, edema due to the inflammatory and fibrous reaction, results in a retained sponge/gauze appearing as a soft-tissue mass with a thick well-defined capsule, having a whorled internal configuration on T2-weighted images. The peripheral calcifications are seen on T1 and T2-weighted images. A complex mass with mixed signal intensity is less commonly seen. Depending on the amount of water content, the signal intensity on T2-weighted images varies from low to high signal intensities. Postcontrast imaging shows peripheral enhancement [Figures 5 and 11].[32]

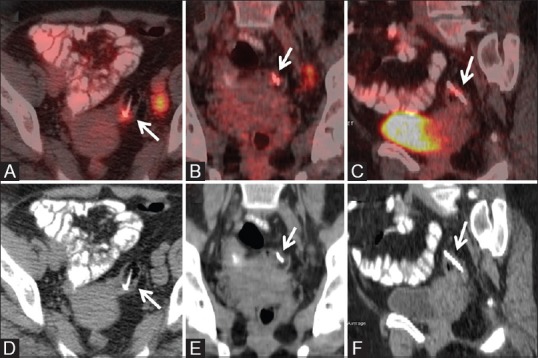

Figure 11 (A-D).

Migrated Copper T in pelvis seen on PET-CT. The axial, coronal and sagittal reformatted images of fused PETCT (A-C) and CT images (D-F) showing an FDG uptake around the foreign body which corresponds to inflammatory changes

Nuclear medicine

With increasing clinical use of PET/CT, few case of imaging appearance has been reported.[33,34] In reported gossypibomas, low central radiotracer uptake with high peripheral uptake corresponding to active inflammatory reaction near fibrotic capsule has been demonstrated. Low-grade tracer uptake is attributed to inflammatory reaction around the foreign body [Figure 11].

A bone scan with technetium-99m-methylene diphosphonate may show extraosseous accumulation of tracer in sites corresponding to the inflammatory granuloma of RSI.[35]

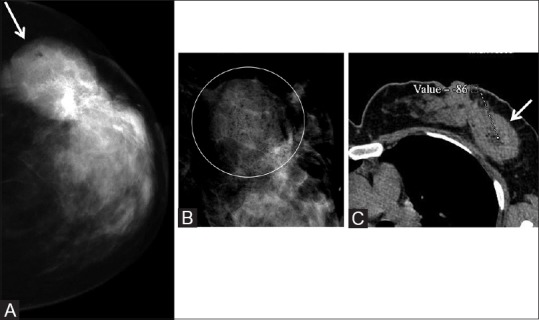

Mammography

A retained sponge on mammography appears as high-density mass with varying appearance. The characteristic twisted radiodense marker clinches the diagnosis.[36] Skin thickening and retraction of skin and nipple may be seen as sequelae to non healing wound and chronic fibrosis [Figures 12 and 13].

Figure 12 (A-C).

A case of retained surgical gauze in breast post surgery. The mammography image showing a high density mass (A). The magnified view shows a few lucent specks (B within the white circle). follow up CT scan showing a mass with low central low HU area in the left breast (C). Continued in Figure 13

Figure 13 (A-E).

(continued from previous Figure 12). MR images of the breast mass are showing isointensity on T1W images, hyperintensity on T2W and T2 fat sat images (A-C respectively). Post contrast fast T1 image showing smooth peripheral enhancement which is merging with the adjacent post-operative changes (D). Subsequent re-exploration revealed retained gauze (E)

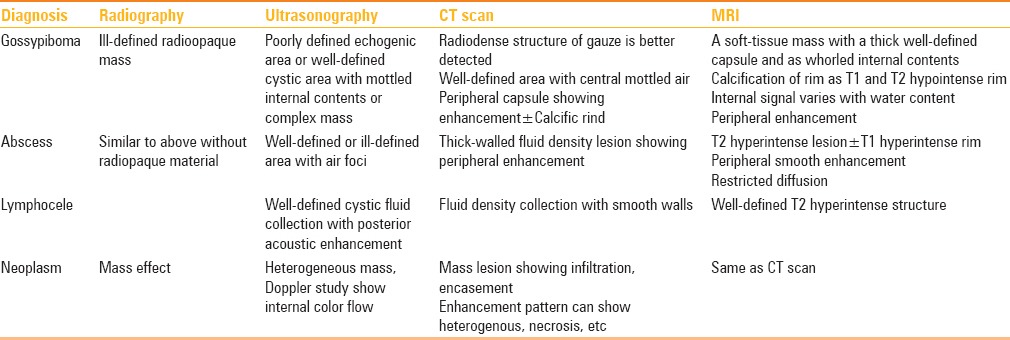

Differential Diagnosis

Presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Differential diagnosis

Newer retained surgical items

Recent advances in biomedical engineering and robotics have considerably improved the techniques of surgery such as minimally invasive procedures, laparoscopic, endoscopic surgeries, and current robotic surgeries. With these, the incidence of retained small and complex surgical instruments such as broken plastic parts, guidewires, clips, trochar, and other miscellaneous items has increased. Contributing factors for these errors amount to a narrow window of surgical access, improper size of instrument used, and difficulty in handling small and complex instruments.

Most of the newer RSI are not limited to only sponges and towels but also radiolucent items plastic and silicone which pose a challenge in identifying on conventional imaging. CT and USG may help in these situations if there is a strong suspicion.

Innovations for Reducing the Incidences

New technologies such as “Electronic Computer Assisted Sponge Counting System” and Radio-Frequency identification sponges (RFID) aim to reduce the incidence with the reasoning that technological error is smaller than human error. A randomized control trial by Greenberg et al. in 2008 concluded that the use of automated counting using barcoded surgical sponges improved the detection of miscounted and misplaced sponges.[37] The effectiveness of radiofrequency detection systems has also been demonstrated in some studies.[38,39]

The barcode-assisted system includes individual surgical sponges bearing two-dimensional barcodes which are read by a scanner before and after surgery. The count is tracked by a computer and displayed on a screen.

The RFID works on the same principle, however, here the scanning of the sponge does not require optical scanning. Instead, the radiofrequency scanner can detect the RFID bearing sponges, even if it is in the patient's body. The RFID machine consists of a front panel scanner, digital display, out-sponge bucket with a radiofrequency sensor, and a wand to scan the patient's body. Before surgery, all the sponges are counted on a front panel of the machine, and after that, the final count is made by counting the unused sponges and sponges thrown into the radiofrequency sensor bucket. Any sponge left inside the patient body is finally scanned with the wand.

An analysis by Regenbogen et al. in 2008 comparing the six strategies of prevention of RSI including traditional intraoperative radiography and novel technologies showed that the newer technologies, especially the barcode system, was more cost effective than intraoperative radiography in making retained sponges as a “Never-Event.”[40]

Use of intraoperative imaging such as intraoperative radiography, fluoroscopy, and ultrasonography also helps in identifying missing instruments. Intraoperative ultrasound is cost effective in localizing and helps in retrieving lost surgical items.[5] However, not many studies have elaborated the effectiveness of ultrasound as compared to other modalities.

Conclusion

Due to the varied appearances of RSI, it is difficult to diagnose them on radiographs. Clinical information, coupled with a high index of suspicion, is mandatory for diagnosis. In dubious cases, confirmation with a second imaging modality can be helpful. Radiologists play a key role in diagnosing retained surgical materials. A reasonable knowledge of this entity with its common presentations should be possessed by all radiologists. In fact, RSI should be considered in the differential diagnoses of a mass or nonspecific imaging findings in a postoperative patient.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Dr. Sneha Zanje for help and support in drafting this article.

References

- 1.Patil KK, Patil SK, Gorad KP, Panchal AS, Arora SS, Gautam RP. Intraluminal migration of surgical sponge: Gossypiboma. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:221–2. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.65195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gibbs VC. Retained surgical items and minimally invasive surgery. World J Surg. 2011;35:1532–9. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-1060-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. The ICD.10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: Diagnostic criteria for research. ICD-10 Classif Ment Behav Disord Diagnostic criteria Res. 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hyslop JW, Maull KI. Natural history of the retained surgical sponge. South Med J. 1982;75:657–60. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198206000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldberg JL, Feldman DL. Implementing AORN recommended practices for prevention of retained Surgical Items. AORN J. 2012;95:205–19. doi: 10.1016/j.aorn.2011.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lata I, Sahu S, Kapoor D. Gossypiboma, a rare cause of acute abdomen: A case report and review of literature. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2011;1:157–60. doi: 10.4103/2229-5151.84805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson JM, Rodriguez A, Chang DT. Foreign body reaction to biomaterials. Semin Immunol. 2008;20:86–100. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ranjan R, Nityasha N, Anubhav P, Arya K, Mishra N. Transvisceral migration of gossypiboma presenting as gastric outlet obstruction managed endoscopically. Int Surg J. 2016;3:1663–5. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zantvoord Y, van der Weiden RMF, van Hooff MHA. Transmural migration of retained surgical sponges: A systematic review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2008;63:465–71. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0b013e318173538e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chopra S, Suri V, Sikka P, Aggarwal N. A Case Series on Gossypiboma-Varied Clinical Presentations and Their Management. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9:QR01–3. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/15927.6978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dakubo J, Clegg-Lamptey JN, Hodasi WM, Obaka HE, Toboh H, Asempa W. An intra-abdominal gossypiboma. Ghana Med J. 2009;43:43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sozutek A, Colak T, Reyhan E, Turkmenoglu O, Akpinar E. Intra-abdominal Gossypiboma Revisited: Various Clinical Presentations and Treatments of this Potential Complication. Indian J Surg. 2015;77:1295–300. doi: 10.1007/s12262-015-1280-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zbara P, Agrawal A, Saeed IT, Utidjian MR. Gossypiboma revisited: A case report and review of the literature. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1998;43:417–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaiser CW, Friedman S, Spurling KP, Slowick T, Kaiser HA. The retained surgical sponge. Ann Surg. 1996;224:79–84. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199607000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Botet del Castillo FX, López S, Reyes G, Salvador R, Llaurado JM, Penalva F, et al. Diagnosis of retained abdominal gauze swabs. Br J Surg. 1995;82:227–8. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800820232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gawande AA, Studdert DM, Orav EJ, Brennan TA, Zinner MJ. Risk factors for retained instruments and sponges after surgery. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:229–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa021721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moffatt-Bruce SD, Cook CH, Steinberg SM, Stawicki SP. Risk factors for retained surgical items: A meta-analysis and proposed risk stratification system. J Surg Res. 2014;190:429–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2014.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wan YL, Ko SF, Ng KK, Cheung YC, Lui KW, Wong HF. Role of CT-guided core needle biopsy in the diagnosis of a gossypiboma: Case report. Abdom Imaging. 2004;29:713–5. doi: 10.1007/s00261-004-0172-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manzella A, Borba Filho P, Albuquerque E, Farias F, Kaercher J. Imaging of gossypibomas: Pictorial review. Am J Roentgenol. 2009:193. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.7132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chagas Neto FA das, Agnollitto PM, Mauad FM, Barreto AR, Muglia VF, Junior JE. Avaliação por imagem dos gossipibomas abdominais. Radiol Bras. 2012;45:53–8. [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Connor AR, Coakley FV, Meng MV, Eberhardt SC. Imaging of Retained Surgical Sponges in the Abdomen and Pelvis. Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180:481–9. doi: 10.2214/ajr.180.2.1800481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abdul-Karim FW, Benevenia J, Pathria MN, Makley JT. Case report 736: Retained surgical sponge (gossypiboma) with a foreign body reaction and remote and organizing hematoma. Skeletal Radiol. 1992;21:466–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00190994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Topal U, Gebitekin C, Tuncel E. Intrathoracic gossypiboma. Am J Roentgenol. 2001;177:1485–6. doi: 10.2214/ajr.177.6.1771485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kokubo T, Itai Y, Ohtomo K, Yoshikawa K, Lio M, Atomi Y. Retained surgical sponges: CT and US appearance. Radiology. 1987;165:415–8. doi: 10.1148/radiology.165.2.3310095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim KS. Changes in computed tomography findings according to the chronicity of maxillary sinus gossypiboma. J Craniofac Surg. 2014;25:e330–3. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000000594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sistla Chandra S, Ramesh A, Karthikeyan SV, Ram D, Ali SM, Subramaniam RV, et al. Gossypiboma presenting as coloduodenal fistula-report of a rare case with review of literature. Int Surg. 2014;99:126–31. doi: 10.9738/INTSURG-D-13-00057.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wan W, Le T, Riskin L, Macario A. Improving safety in the operating room: A systematic literature review of retained surgical sponges. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2009;22:207–14. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e328324f82d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu YY, Cheung YC, Ko SF, Ng SH. Calcified reticulate rind sign: A characteristic feature of gossypiboma on computed tomography. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:4927–9. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i31.4927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Machado DM, Zanetti G, Araujo Neto CA, Nobre LF, Meirelles GS, Silva JL, et al. Thoracic textilomas: CT findings. J Bras Pneumol. 2014;40:535–42. doi: 10.1590/S1806-37132014000500010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sheehan RE, Sheppard MN, Hansell DM. Retained intrathoracic surgical swab: CT appearances. J Thorac Imaging. 2000;15:61–4. doi: 10.1097/00005382-200001000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sugano S, Suzuki T, Iinuma M, Mizugami H, Kagesawa M, Ozawa K, et al. Gossypiboma: Diagnosis with ultrasonography. J Clin Ultrasound. 1993;21:289–92. doi: 10.1002/jcu.1870210415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim CK, Park BK, Ha H. Gossypiboma in abdomen and pelvis: MRI findings in four patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189:814–7. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yuh-Feng T, Chin-Chu W, Cheng-Tau S, Min-Tsung T. FDG PET CT features of an intraabdominal gossypiboma. Clin Nucl Med. 2005;30:561–3. doi: 10.1097/01.rlu.0000170227.56173.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu JQ, Milestone BN, Parsons RB, Doss M, Hass N. Findings of intramediastinal gossypiboma with F-18 FDG PET in a melanoma patient. Clin Nucl Med. 2008;33:344–5. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e31816a78b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomas BG, Silverman ED. Focal Uptake of Tc-99m MDP in a Gossypiboma. Clin Nucl Med. 2008;33:290–1. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e3181662b41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yeniceri O, Balci P, Cullu N, Deveer M. Gossipyboma in the Breast: A Rare Case Report. J Med Cases. 2014;5:140–2. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Greenberg CC, Diaz-Flores R, Lipsitz SR, Regenbogen SC, Mulholland L, Mearn F, et al. Bar-coding surgical sponges to improve safety: A randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2008;247:612–6. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181656cd5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rupp CC, Kagarise MJ, Nelson SM, Deal AM, Phillips S, Chadwick J, et al. Effectiveness of a radiofrequency detection system as an adjunct to manual counting protocols for tracking surgical sponges: A prospective trial of 2,285 patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215:524–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Williams TL, Tung DK, Steelman VM, Chang PK, Szekendi MK. Retained surgical sponges: Findings from incident reports and a cost-benefit analysis of radiofrequency technology. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;219:354–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Regenbogen SE, Greenberg CC, Resch SC, Kollengode A, Cima RR, Zinner MJ, et al. Prevention of retained surgical sponges: A decision-analytic model predicting relative cost-effectiveness. Surgery. 2009;145:527–35. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]