Highlights

-

•

Inpatient diabetes control in non-ICU patients can improve clinical outcomes.

-

•

Insulin administration is a mainstay of hyperglycemia management in the wards.

-

•

Avoidance of hypoglycemia is important during glycemia management.

-

•

Several diabetes patient groups will require different treatment approach.

-

•

Future glycemia treatment algorithms should allow individualization of therapy.

Keywords: Inpatient hyperglycemia, Management, Steroid-induced hyperglycemia, Hypoglycemia

Abbreviations: BBI, basal-bolus insulin; BI, basal insulin; BG, blood glucose

Abstract

Inpatient diabetes is a common medical problem encountered in up to 25–30% of hospitalized patients. Several prospective trials showed benefits of structured insulin therapy in managing inpatient hyperglycemia albeit in the expense of high hypoglycemia risk. These approaches, however, remain underutilized in hospital practice. In this review, we discuss clinical applications and limitations of current therapeutic strategies. Considerations for glycemic strategies in special clinical populations are also discussed. We suggest that given the complexity of inpatient glycemic control factors, the “one size fits all” approach should be modified to safe and less complex patient-centered evidence-based treatment strategies without compromising the treatment efficacy.

Introduction

About 25–30% of hospitalized patients have a known diagnosis of diabetes while additional 5–10% of patients will have the diagnosis discovered during admission for the first time [1], [2], [3], [4]. Over the last decade, the inpatient diabetes prevalence remains steady as was reported by the same group of authors in 2002 and 2016 [3], [5]. The Endocrine Society clinical practice guidelines suggest that, based on retrospective and observational evidence, inpatient random blood glucose (BG) levels below 180 mg/dL and fasting BG below 140 mg/dL are more likely to be associated with better clinical outcomes such as reduced risk of infections, less disability after hospital discharge, and improved perioperative complications in non-critically ill medical and surgical patients [1]. However, in prospective trials, the positive impact of BG goal-driven glycemic control in non-intensive care unit (non-ICU) setting was less evident [6] raising a question if intensive management of hyperglycemia in non-ICU setting is of targetable clinical benefit. Only one randomized controlled trial conducted in surgical patients on the floor showed that scheduled insulin therapy targeting recommended inpatient glycemic goals reduces incidence of infections and combined post-operative complication rate [7]. Interventional studies in medical patients with diabetes could not reproduce similar benefits [6]. It is important to recognize that to date there are no prospective trials that tested clinical efficacy and outcomes of targeting different inpatient BG goals in non-critically ill patients.

Insulin therapy is suggested as cornerstone treatment strategy in the management of inpatient diabetes [1], [8]. Over the last 20 years of intensive clinical research, we witnessed a remarkable move away from the old approach of using insulin per “sliding scale” due to its poor glycemic efficacy and potential harms in the management of inpatient diabetes [9], [10]. However, with the evolution of evidence supporting anti-hyperglycemic efficacy of basal-bolus insulin (BBI), high rates of hypoglycemia were reported suggesting that even in the hands of experienced endocrinologists conducting these trials, new insulin strategies may not be as harmless as originally thought [7], [11], [12], [13], [14]. While the clinical benefits from achieving proposed glycemic goals in non-critically ill patients with diabetes are yet to be determined at least in medical patients, insulin-induced hypoglycemia appears to be more of a concern during inpatient diabetes management [15]. Therefore, newer strategies utilizing non-insulin approaches in the management of inpatient hyperglycemia were proposed and recently studied in hospitalized patients with diabetes [16], [17].

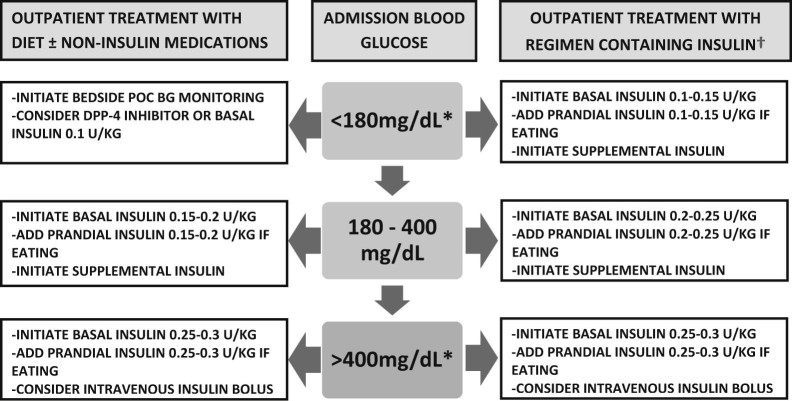

In addition to the risk of hypoglycemia due to intensive inpatient insulin regimens, some other factors may lessen current enthusiasm in the field and, most importantly, uptake of current anti-hyperglycemic strategies by non-endocrinologists. System-based issues, provider-related factors, and patient-specific presentation all cause unavoidable confusion among the hospital administrators and non-endocrinology providers in regard to how hyperglycemia should be managed in the non-ICU setting. In Fig. 1, we combined potential contributors to the low adherence to current glycemic management recommendations. Of note, it is very difficult to enforce hospital administration to implement hyperglycemia treatment strategies in non-critically ill patients unless the BG metric becomes one of the inpatient care goals or part of patient care bundles. A group of experts further delineated current problems in managing inpatient diabetes and drew a road map to overcome the problems [18].

Figure 1.

Barriers to achieving glycemic control in non-critically ill patients with diabetes.

Each patient with diabetes admitted to the medical or surgical ward is unique in his/her presentation. Underlying co-morbidities, admission BG level and hemoglobin A1c, presenting complaints, outpatient insulin use, diabetes duration, co-administration of steroids, and nutritional status are among those variables that should influence the decision-making process during evaluation for anti-hyperglycemic therapy. All this information is objectively difficult to ascertain during the admission by internal medicine providers. Therefore, it may still be tempting for non-endocrinologists to use a reactive approach in the management of hyperglycemia by initiating “sliding scale” insulin regimen in spite of the evidence that this strategy can not only be harmful but also does not address pathophysiology of glucose dysregulation in hospitalized diabetes patients.

In this review, we summarized the results of recent evidence from the interventional trials on diabetes control in non-critically ill patients. We will discuss unique aspects of diabetes care in special patient groups. Furthermore, we suggest potential pathways to address both efficacy and safety of diabetes treatment approaches in the hospital.

Glycemic management of hospitalized patient with diabetes

Patients admitted to the hospital should be evaluated for a history of diabetes, and if the diagnosis is confirmed, bedside glucose monitoring and a therapeutic plan to manage hyperglycemia should be initiated. Hemoglobin A1c measurement on admission will identify patients in whom optimization of outpatient diabetes treatment is indicated. It was recently shown that, in medical and surgical non-critically ill patients, an admission A1c >9.0% is associated with decreased likelihood of achieving optimal inpatient glucose control and higher insulin requirements [19]. Furthermore, an A1c >9.0% will help identify the individuals who may benefit from addition of insulin therapy on discharge [20]. Hospitalized patients without known history of diabetes should be strongly considered for diabetes screening. Measurement of A1c or random BG may offer benefits in identifying new diabetes diagnosis [4] though more prospective studies needed to fully understand cost-effectiveness of universal inpatient diabetes screening.

Patients with type 1 diabetes should be clearly identified and promptly treated using scheduled insulin therapy. In the absence of prospective trials in insulin-dependent diabetes patients, the starting total dose of basal and bolus insulin therapy should range between 0.3 and 0.5 units/kg/day. The 2014 inpatient diabetes national survey in the UK revealed that out of all registered diabetic ketoacidosis cases, 7.8% developed de novo in already hospitalized patients [21] suggesting the need for more vigilance in the care of insulin-dependent diabetes in the hospital. In type 2 diabetes patients, we have limited options for the management of hyperglycemia in the medical or surgical wards [22]. Insulin therapy is a treatment of choice that addresses pathophysiology of glucoregulation. The provision of basal insulin (BI) will target fasting hyperglycemia and help to alleviate stress hyperglycemia due to insulin resistance regardless of the patient's nutritional state. Administration of short-acting prandial insulin in eating patients will address abnormalities in post-prandial glucose control. For eating patients, this strategy is called a BBI regimen [13]. However, proof of concept studies showed that for some type 2 diabetes subjects BI plus correction insulin regimen could be another alternative in the management of inpatient hyperglycemia [11].

The important questions in hospital practice are to identify patients who will benefit from insulin prescription and how to start and tailor the insulin regimen. Prospective trials that compared efficacy of BBI therapy versus either sliding scale insulin or premixed insulin enrolled type 2 diabetes subjects with admission BG of 140–400 mg/dL and who had no clinical and biochemical evidence of organ failure, received no corticosteroid therapy, and had no indication for ICU transfer; patients had different baseline characteristics [7], [12], [13], [14], [23]. Further analyses demonstrate that while there were similarities in the average admission A1c of 8–9% and BG of 200–230 mg/dL among the studies, the end of study insulin requirements were discordant. Average final total daily insulin dose was 30–40 units/day or 0.3–0.4 units/kg/day for those patients who had diabetes duration <10 years and were mostly treated with diet and/or non-insulin agents before admission [7], [11], [13]. In contrast, in the trials that enrolled patients who had type 2 diabetes for >10 years and preadmission insulin usage was recorded in >50% of the subjects, the mean effective daily insulin dose ranged between 0.5 and 0.6 units/kg/day [12], [14], [23], [24]. The evidence guiding initial management of diabetes in patients who are euglycemic on presentation, admitted with severe non-ketotic hyperglycemia, may require glucocorticosteroids and/or exhibit signs and symptoms of organ failure is limited.

Following the initiation of therapy, insulin titration strategies are less well defined as they were not formally tested in prospective trials. One should keep in mind that the risks and benefits of aggressive BG lowering are unknown while the risk of hypoglycemia in hospitalized non-critically ill patients is considerable and associated with adverse clinical outcomes [25], [26]. With known inter- and intra-individual variations of pharmacokinetics and unique mechanism of appearance in the systemic circulation of basal insulin analogs glargine and detemir [27], [28], large and frequent changes in insulin prescription should be avoided to reduce the risk of hypoglycemia. As was emphasized by the Endocrine Society clinical practice recommendations [1], insulin therapy can be increased by 10–20% if BG level is above the target; similarly, 10–20% reduction in insulin prescription should be considered if BG is below 100 mg/dL during the hospitalization.

Correction insulin, a.k.a. “sliding scale insulin”, should be used only as an adjunct therapeutic modality in hospitalized patients. By itself, this strategy does not improve patient outcomes and can significantly increase risk of hypoglycemia or severe hyperglycemia in non-critically ill setting [29], [30], [31]. When it is used as a supplemental insulin together with BBI or BI regimen, it can help to manage episodes of unexpected hyperglycemia [1]. There is no single universal formula to predict precisely the amount of correction insulin needed [1]. Considering that patient's total daily insulin dose and, hence, insulin sensitivity can change during the hospitalization, a 1700 rule may allow dynamic optimization of the correction factor to guide insulin supplementation [32].

Hypoglycemia mitigation strategies

While insulin is the most potent and proven agent to manage diabetes in non-critically ill hospitalized patients, this therapeutic strategy may carry significant risk of hypoglycemia [16]. Inpatient hypoglycemia defined as BG < 70 mg/dL is associated with adverse outcomes in diabetes patients [25], [26]. There is a debate whether hypoglycemia is a marker or cause of poor patient outcomes [15]. Until this question is resolved, we should clearly avoid and prevent hypoglycemia in hospitalized patients. The frequency of hypoglycemia in inpatient diabetes in the ward can vary anywhere from 3.5% to 35% depending on the setup of the study with prospective trials that evaluated the BBI therapy recording higher incidence likely due to the nature of the design requiring more frequent glucose monitoring [7], [12], [13], [14], [23], [26], [33]. One approach to reduce inpatient hypoglycemia would be to initiate BBI regimen in insulin-naïve patient at a dose not exceeding 0.3 units/kg/day. Alternative therapeutic strategies have been recently tested in randomized controlled studies. In patients with less pronounced admission hyperglycemia, therapeutic strategies containing supplemental insulin and either basal insulin dosed at 0.25 units/kg/day, combination of basal insulin and a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor sitagliptin, or sitagliptin resulted in lower incidence of hypoglycemia at 13%, 7%, and 4%, respectively [11], [34]; the hypoglycemia rates were not different between sitagliptin-based groups [34]. In one retrospective case-control study, the authors suggested an increasing risk of hypoglycemia when patients are treated with weight-based insulin regimens above 0.4 units/kg/day [33].

In addition to the intensive glucose management, other clinical factors should be strongly considered in evaluating risk of hypoglycemia in diabetes patients. Kidney and liver failure, variable caloric intake, recovery from underlying illness, mismatch between short-acting insulin administration and meal availability, participation in physical rehabilitation program, de-escalation of corticosteroid therapy, and/or unrecognized adrenal insufficiency can all predispose to hypoglycemia. Use of intermediate action insulin NPH as a basal insulin or inpatient prescription of premixed insulin is more likely to be associated with risk of hypoglycemia compared with administration of insulin glargine-based treatments [33]. In post-hoc analysis of prospective studies conducted in non-critically ill diabetes patients, the investigators found that hypoglycemia highly correlated with patient's age and renal insufficiency [35]. Table 1 summarizes important clinical factors that could affect glycemic control in non-ICU diabetic patients. In an attempt to address modifiable factors predisposing to hypoglycemia, providers should always carefully assess and monitor the patient's condition on a daily basis, appropriately recognize changes in nutritional patterns and prescription of concomitant medications, use less intense insulin regimens or insulin preparations with the lowest risk of hypoglycemia, and appropriately de-intensify therapy when BG levels show downward trends or decrease below 100 mg/dL.

Table 1.

Clinical factors affecting glycemic management in non-critically ill diabetes patients

| 1. Factors that predispose to hyperglycemia: |

| • Glucocorticosteroid use |

| • Infection |

| • Stress of underlying illness |

| • Increase in carbohydrate intake |

| • Parenteral nutrition |

| • Inadequate glycemic therapy |

| 2. Factors that predispose to improved glucose control and/or hypoglycemia: |

| • Renal dysfunction |

| • Advanced age |

| • Discontinuation or reduction in glucocorticosteroids |

| • Decreased carbohydrate intake (NPO status, interruption of tube feeding) |

| • Organ failure (heart, liver, kidney) |

| • Adrenal insufficiency |

| • Malnutrition/frailty |

| • Resolution of underlying illness |

| • Increased physical activity/mobilization |

| • Polypharmacy |

| • Resolution of hyperglycemia (via alleviation of glucosetoxicity) |

Managing hyperglycemia in special clinical populations

Previous prospective interventional trials evaluated insulin delivery strategies in patients with limited number of associated co-morbid conditions, which expectedly limits the applicability of the findings to other hospitalized patient populations. The issue with diabetes management in special patient groups is one of the prioritized topics of future inpatient diabetes research [18].

Severe non-ketotic hyperglycemia

As discussed above, inpatient hyperglycemia studies excluded patients with admission BG >400 mg/dL. Patients with acute severe hyperglycemia will have transient decreases in insulin production and insulin sensitivity, a phenomenon called “glucosetoxicity” [36]. To lower glycemia in a short term, intravenous delivery of insulin and intensive rehydration should be strongly considered. In the non-ICU setting, continuous insulin infusion could be a safe and efficacious strategy [37], but logistically very difficult to implement in routine inpatient practice. In the author's experience, intravenous boluses of regular insulin at the dose 0.10–0.15 units/kg every 60–120 mins accompanied by bedside glucose monitoring could be safely and promptly done in the wards until BG is reduced below 250–300 mg/dL. Use of “sliding scale” insulin to treat severe hyperglycemia is not recommended due to potential insulin absorption issues in dehydrated patients with severe hyperglycemia and insulin “stacking” phenomenon. Following the rehydration and resolution of hyperglycemia, providers should evaluate for factors that led to the development of severe hyperglycemia.

Steroid-induced hyperglycemia

BBI therapy is a first choice of inpatient diabetes management in many hospitalized patients; however, less is known about the optimal insulin regimens to manage steroid-induced hyperglycemia [1], [18], [38]. Steroids reduce insulin sensitivity [39], which compellingly calls for more intensive management of the post-prandial glucose metabolism. Recently, few studies have evaluated the efficacy of different insulin regimens in the management of steroid-induced hyperglycemia in diabetes patients in the wards [40], [41], [42], [43], [44]. These studies were different in design, patient population, and prescription of glucocorticoid studied. Evidence suggests that diabetes patients receiving the more potent steroid dexamethasone may require insulin regimens up to 1.0–1.2 units/kg/day [40], [43] while insulin needs for the patients treated with hydrocortisone and prednisone could be lower at 0.6–0.7 units/kg/day [41], [42]. In the only prospective trial that addressed steroid-induced hyperglycemia management, Grommesh et al. demonstrated that patients required a mean total daily insulin dose of 0.4 units/kg; of note, both diabetic and non-diabetic patients were studied in the trial [44]. Addition of a single neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH) dose during initiation of prednisone has been suggested [45] and recently studied [44]; however, this approach appears to be complex. In our experience, and based on the studies that addressed the management of dexamethasone-induced hyperglycemia, BBI regimen split as 70% of prandial insulin and 30% of basal insulin administered as once daily insulin glargine or twice daily insulin detemir or NPH can provide more flexibility in intensification and then de-escalation of insulin therapy without causing fasting hypoglycemia. More research is needed to identify simple and effective insulin regimens managing steroid-induced hyperglycemia.

Hyperglycemia in patients with renal insufficiency

Patients with diabetes and declining kidney function are at high risk for hypoglycemia [46]. Decreased insulin clearance, impaired renal gluconeogenesis, malnutrition, and hypoglycemic agents are among the main factors predisposing to hypoglycemia in diabetic ESRD [47], [48], [49], [50], [51]. Inpatient diabetes treatment studies excluded patient with moderate to severe chronic renal insufficiency or acute kidney injury. Only a few studies addressed the safety and efficacy of diabetes management in this patient population. In hospitalized patients with renal insufficiency, administration of BBI in the dose of 0.25 units/kg/day was less likely to cause hypoglycemia and as effective in the management of diabetes compared with the regimen of 0.5 units/kg/day [52]. Therefore, based on the physiology of glucose metabolism in patients with renal impairment and limited research in the field, initiation of BI at the dose of 0.10–0.15 units/kg/day, if used as a monotherapy, or BBI in the dose not exceeding 0.25–0.30 units/kg/day should be considered in non-critically ill subjects with renal failure including end-stage renal disease.

Hyperglycemia during enteral and parenteral nutrition

Only one prospective trial evaluated the effectiveness of different insulin regimens in managing hyperglycemia in hospitalized patients receiving enteral nutrition support [53]. In this study, patients with and without diabetes and BG levels >140 mg/dL were randomized to receive either a standard therapy consisting of sliding scale insulin or insulin glargine along with correctional insulin administered once daily. Of note, 48% of patients in the sliding scale group required rescue therapy with long-acting insulin due to persistent hyperglycemia. Patients with diabetes required a total daily dose of 0.61 ± 0.28 units/kg/day. The results of this investigation suggest that starting a long-acting insulin along with correctional short-acting insulin is an effective strategy to manage hyperglycemia during enteral nutrition.

Several retrospective studies demonstrated that administration of insulin glargine at an average dose of 34 units/day [54], insulin NPH every 6 hours [55] or 70/30-biphasic insulin thrice daily [56] could be used as well for inpatient hyperglycemia management. The use of NPH may be preferable because of the shorter half-life that facilitates its titration or discontinuation in the event tube feedings are stopped and lower cost. Not infrequently, tube feeds could be interrupted, which can increase the risk of hypoglycemia in these patients receiving long-acting insulin therapy. Prompt initiation of intravenous fluids containing 10% dextrose at the rate of enteral nutrition therapy could reduce hypoglycemia risk until enteral nutrition is re-established [57].

Insulin is the treatment of choice to control hyperglycemia during total parenteral nutrition (TPN). Both subcutaneous and intravenous insulin have been shown to be effective in managing hyperglycemia in these patients [58], [59], [60]. In general, adding insulin to the TPN mixture is clinically safe and effective in controlling hyperglycemia. The evidence suggests that TPN insulin supplementation at the ratio of 1 unit per 10–11 grams of carbohydrates will control hyperglycemia in diabetes patients without significant risk of hypoglycemia [59], [61]. Providers should consider using weight-based dose of basal insulin administered subcutaneously to prevent fasting hyperglycemia if delivery of TPN mixed with insulin is interrupted.

Conclusions

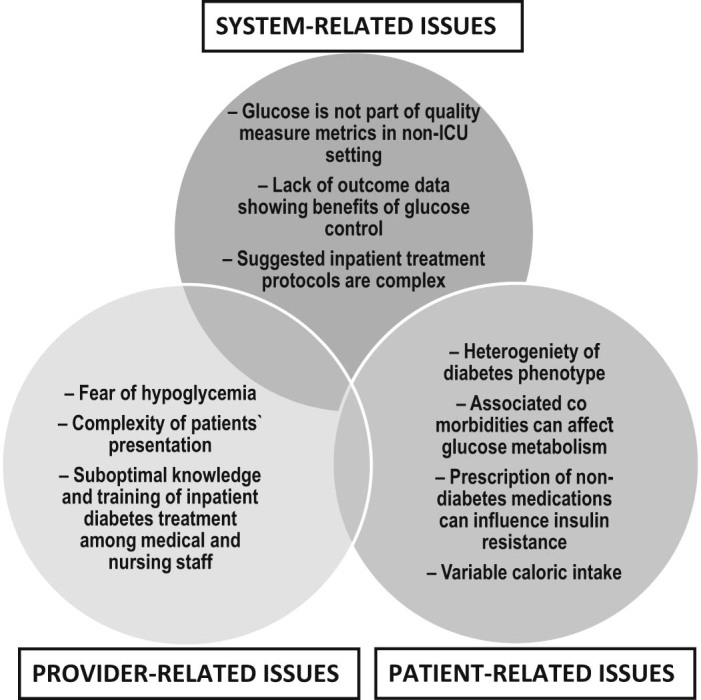

In non-critically ill patients, therapeutic strategies aiming to control hyperglycemia should consider use of regimens with low risk of hypoglycemia. Suggested hospital glycemic protocols [62], [63] are a welcome development to reduce hyperglycemia in the hospitalized patients, but these insulin regimens may not take into account heterogeneity of the diabetes phenotypes in the hospital wards, which can pose a risk of hypoglycemia if these protocols are universally used. In fact, efficacy and safety of different initial insulin-containing regimens have not been tested in head to head trials so providers are left alone in selecting the best insulin regimen to treat hyperglycemia and, often, they choose the path of least resistance and initiate “sliding scale” insulin as therapy of choice. As it occurred with the outpatient diabetes management strategies, we should shift from “one size fits all” approach to more patient-centered treatment strategies that take into account the patient's co-morbidities, risk of hypoglycemia, duration of diabetes, and use of medications that affect insulin-resistance. Fig. 2 presents an approach that combines existing clinical evidence and patient-centered considerations in selecting safe and effective regimens to control diabetes in non-critically ill patients.

Figure 2.

Proposed approach to initial management of hyperglycemia in non-critically ill patient with diabetes based on admission glucose level and outpatient diabetes treatment.

POC – point of care; BG – blood glucose; DPP-4 – dipeptidyl peptidase-4.

* – non-critically ill diabetic patients admitted with these BG ranges are typically excluded from interventional studies.

† – consider continuation of home insulin regimen if compliance is confirmed and there are no clinical factors that may predispose to hypoglycemia.

Conflict of interests

A.R.G. declares no competing interests. A.R.G. is an employee of the US Department of Veterans Affairs and his opinions expressed in this manuscript are the author's personal opinions and do not necessarily represent the opinion of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

References

- 1.Umpierrez G.E., Hellman R., Korytkowski M.T., Kosiborod M., Maynard G.A., Montori V.M. Management of hyperglycemia in hospitalized patients in non-critical care setting: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(1):16–38. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-2098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bach L.A., Ekinci E.I., Engler D., Gilfillan C., Hamblin P.S., MacIsaac R.J. The high burden of inpatient diabetes mellitus: the Melbourne public hospitals diabetes inpatient audit. Med J Aust. 2014;201(6):334–338. doi: 10.5694/mja13.00104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fayfman M., Vellanki P., Alexopoulos A.S., Buehler L., Zhao L., Smiley D. Report on racial disparities in hospitalized patients with hyperglycemia and diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(3):1144–1150. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-3220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sentell T.L., Cheng Y., Saito E., Seto T.B., Miyamura J., Mau M. The burden of diagnosed and undiagnosed diabetes in Native Hawaiian and Asian American hospitalized patients. J Clin Transl Endocrinol. 2015;2(4):115–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jcte.2015.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Umpierrez G.E., Isaacs S.D., Bazargan N., You X., Thaler L.M., Kitabchi A.E. Hyperglycemia: an independent marker of in-hospital mortality in patients with undiagnosed diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(3):978–982. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.3.8341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murad M.H., Coburn J.A., Coto-Yglesias F., Dzyubak S., Hazem A., Lane M.A. Glycemic control in non-critically ill hospitalized patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(1):49–58. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Umpierrez G.E., Smiley D., Jacobs S., Peng L., Temponi A., Mulligan P. Randomized study of basal-bolus insulin therapy in the inpatient management of patients with type 2 diabetes undergoing general surgery (RABBIT 2 surgery) Diabetes Care. 2011;34(2):256–261. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Umpierrez G.E., Korytkowski M. Is incretin-based therapy ready for the care of hospitalized patients with type 2 diabetes?: insulin therapy has proven itself and is considered the mainstay of treatment. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(7):2112–2117. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Umpierrez G.E., Palacio A., Smiley D. Sliding scale insulin use: myth or insanity? Am J Med. 2007;120(7):563–567. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.05.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirsch I.B. Sliding scale insulin–time to stop sliding. JAMA. 2009;301(2):213–214. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Umpierrez G.E., Smiley D., Hermayer K., Khan A., Olson D.E., Newton C. Randomized study comparing a basal-bolus with a basal plus correction insulin regimen for the hospital management of medical and surgical patients with type 2 diabetes: basal plus trial. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(8):2169–2174. doi: 10.2337/dc12-1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Umpierrez G.E., Hor T., Smiley D., Temponi A., Umpierrez D., Ceron M. Comparison of inpatient insulin regimens with detemir plus aspart versus neutral protamine Hagedorn plus regular in medical patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(2):564–569. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Umpierrez G.E., Smiley D., Zisman A., Prieto L.M., Palacio A., Ceron M. Randomized study of basal-bolus insulin therapy in the inpatient management of patients with type 2 diabetes (RABBIT 2 trial) Diabetes Care. 2007;30(9):2181–2186. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meyer C., Boron A., Plummer E., Voltchenok M., Vedda R. Glulisine versus human regular insulin in combination with glargine in noncritically ill hospitalized patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized double-blind study. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(12):2496–2501. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brutsaert E., Carey M., Zonszein J. The clinical impact of inpatient hypoglycemia. J Diabetes Complications. 2014;28(4):565–572. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwartz S., DeFronzo R.A. The use of non-insulin anti-diabetic agents to improve glycemia without hypoglycemia in the hospital setting: focus on incretins. Curr Diab Rep. 2014;14(3):466. doi: 10.1007/s11892-013-0466-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Umpierrez G.E., Schwartz S. Use of incretin-based therapy in hospitalized patients with hyperglycemia. Endocr Pract. 2014;20(9):933–944. doi: 10.4158/EP13471.RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Draznin B., Gilden J., Golden S.H., Inzucchi S.E., Investigators P., Baldwin D. Pathways to quality inpatient management of hyperglycemia and diabetes: a call to action. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(7):1807–1814. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pasquel F.J., Gomez-Huelgas R., Anzola I., Oyedokun F., Haw J.S., Vellanki P. Predictive value of admission hemoglobin A1c on inpatient glycemic control and response to insulin therapy in medicine and surgery patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(12) doi: 10.2337/dc15-1835. e202–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Umpierrez G.E., Reyes D., Smiley D., Hermayer K., Khan A., Olson D.E. Hospital discharge algorithm based on admission HbA1c for the management of patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(11):2934–2939. doi: 10.2337/dc14-0479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dhatariya K.K., Nunney I., Higgins K., Sampson M.J., Iceton G. National survey of the management of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) in the UK in 2014. Diabet Med. 2016;33(2):252–260. doi: 10.1111/dme.12875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mendez C.E., Umpierrez G.E. Pharmacotherapy for hyperglycemia in noncritically ill hospitalized patients. Diabetes Spectr. 2014;27(3):180–188. doi: 10.2337/diaspect.27.3.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bellido V., Suarez L., Rodriguez M.G., Sanchez C., Dieguez M., Riestra M. Comparison of basal-bolus and premixed insulin regimens in hospitalized patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(12):2211–2216. doi: 10.2337/dc15-0160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vellanki P., Bean R., Oyedokun F.A., Pasquel F.J., Smiley D., Farrokhi F. Randomized controlled trial of insulin supplementation for correction of bedtime hyperglycemia in hospitalized patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(4):568–574. doi: 10.2337/dc14-1796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garg R., Hurwitz S., Turchin A., Trivedi A. Hypoglycemia, with or without insulin therapy, is associated with increased mortality among hospitalized patients. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(5):1107–1110. doi: 10.2337/dc12-1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Turchin A., Matheny M.E., Shubina M., Scanlon J.V., Greenwood B., Pendergrass M.L. Hypoglycemia and clinical outcomes in patients with diabetes hospitalized in the general ward. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(7):1153–1157. doi: 10.2337/dc08-2127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heise T., Meneghini L.F. Insulin stacking versus therapeutic accumulation: understanding the differences. Endocr Pract. 2014;20(1):75–83. doi: 10.4158/EP13090.RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heise T., Pieber T.R. Towards peakless, reproducible and long-acting insulins. An assessment of the basal analogues based on isoglycaemic clamp studies. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2007;9(5):648–659. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2007.00756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dickerson L.M., Ye X., Sack J.L., Hueston W.J. Glycemic control in medical inpatients with type 2 diabetes mellitus receiving sliding scale insulin regimens versus routine diabetes medications: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2003;1(1):29–35. doi: 10.1370/afm.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Golightly L.K., Jones M.A., Hamamura D.H., Stolpman N.M., McDermott M.T. Management of diabetes mellitus in hospitalized patients: efficiency and effectiveness of sliding-scale insulin therapy. Pharmacotherapy. 2006;26(10):1421–1432. doi: 10.1592/phco.26.10.1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Queale W.S., Seidler A.J., Brancati F.L. Glycemic control and sliding scale insulin use in medical inpatients with diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(5):545–552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davidson P.C., Hebblewhite H.R., Steed R.D., Bode B.W. Analysis of guidelines for basal-bolus insulin dosing: basal insulin, correction factor, and carbohydrate-to-insulin ratio. Endocr Pract. 2008;14(9):1095–1101. doi: 10.4158/EP.14.9.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rubin D.J., Rybin D., Doros G., McDonnell M.E. Weight-based, insulin dose-related hypoglycemia in hospitalized patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(8):1723–1728. doi: 10.2337/dc10-2434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Umpierrez G.E., Gianchandani R., Smiley D., Jacobs S., Wesorick D.H., Newton C. Safety and efficacy of sitagliptin therapy for the inpatient management of general medicine and surgery patients with type 2 diabetes: a pilot, randomized, controlled study. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(11):3430–3435. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Farrokhi F., Klindukhova O., Chandra P., Peng L., Smiley D., Newton C. Risk factors for inpatient hypoglycemia during subcutaneous insulin therapy in non-critically ill patients with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2012;6(5):1022–1029. doi: 10.1177/193229681200600505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Poitout V., Robertson R.P. Glucolipotoxicity: fuel excess and beta-cell dysfunction. Endocr Rev. 2008;29(3):351–366. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smiley D., Rhee M., Peng L., Roediger L., Mulligan P., Satterwhite L. Safety and efficacy of continuous insulin infusion in noncritical care settings. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(4):212–217. doi: 10.1002/jhm.646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Low Wang C.C., Draznin B. Use of NPH insulin for glucocorticoid-induced hyperglycemia. Endocr Pract. 2016;22(2):271–273. doi: 10.4158/EP151101.CO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rizza R.A., Mandarino L.J., Gerich J.E. Cortisol-induced insulin resistance in man: impaired suppression of glucose production and stimulation of glucose utilization due to a postreceptor detect of insulin action. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1982;54(1):131–138. doi: 10.1210/jcem-54-1-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brady V., Thosani S., Zhou S., Bassett R., Busaidy N.L., Lavis V. Safe and effective dosing of basal-bolus insulin in patients receiving high-dose steroids for hyper-cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and dexamethasone chemotherapy. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2014;16(12):874–879. doi: 10.1089/dia.2014.0115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burt M.G., Drake S.M., Aguilar-Loza N.R., Esterman A., Stranks S.N., Roberts G.W. Efficacy of a basal bolus insulin protocol to treat prednisolone-induced hyperglycaemia in hospitalised patients. Intern Med J. 2015;45(3):261–266. doi: 10.1111/imj.12680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dhital S.M., Shenker Y., Meredith M., Davis D.B. A retrospective study comparing neutral protamine Hagedorn insulin with glargine as basal therapy in prednisone-associated diabetes mellitus in hospitalized patients. Endocr Pract. 2012;18(5):712–719. doi: 10.4158/EP11371.OR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gosmanov A.R., Goorha S., Stelts S., Peng L., Umpierrez G.E. Management of hyperglycemia in diabetic patients with hematological malignancies during dexamethasone therapy. Endocr Pract. 2013:1–14. doi: 10.4158/EP12256.OR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grommesh B., Lausch M.J., Vannelli A.J., Mullen D.M., Bergenstal R.M., Richter S.A. Hospital insulin protocol aims for glucose control in glucocorticoid-induced hyperglycemia. Endocr Pract. 2016;22(2):180–189. doi: 10.4158/EP15818.OR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clore J.N., Thurby-Hay L. Glucocorticoid-induced hyperglycemia. Endocr Pract. 2009;15(5):469–474. doi: 10.4158/EP08331.RAR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gosmanov A.R., Gosmanova E.O., Kovesdy C.P. Evaluation and management of diabetic and non-diabetic hypoglycemia in end-stage renal disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016;31(1):8–15. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfv258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kovesdy C.P., Sharma K., Kalantar-Zadeh K. Glycemic control in diabetic CKD patients: where do we stand? Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52(4):766–777. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Williams M.E., Garg R. Glycemic management in ESRD and earlier stages of CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;63(2 Suppl. 2):S22–38. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gerich J.E., Meyer C., Woerle H.J., Stumvoll M. Renal gluconeogenesis: its importance in human glucose homeostasis. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(2):382–391. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.2.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Park J., Lertdumrongluk P., Molnar M.Z., Kovesdy C.P., Kalantar-Zadeh K. Glycemic control in diabetic dialysis patients and the burnt-out diabetes phenomenon. Curr Diab Rep. 2012;12(4):432–439. doi: 10.1007/s11892-012-0286-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.National Kidney F. KDOQI clinical practice guideline for diabetes and CKD: 2012 update. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60(5):850–886. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Baldwin D., Zander J., Munoz C., Raghu P., DeLange-Hudec S., Lee H. A randomized trial of two weight-based doses of insulin glargine and glulisine in hospitalized subjects with type 2 diabetes and renal insufficiency. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(10):1970–1974. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Korytkowski M.T., Salata R.J., Koerbel G.L., Selzer F., Karslioglu E., Idriss A.M. Insulin therapy and glycemic control in hospitalized patients with diabetes during enteral nutrition therapy: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(4):594–596. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fatati G., Mirri E., Del Tosto S., Palazzi M., Vendetti A.L., Mattei R. Use of insulin glargine in patients with hyperglycaemia receiving artificial nutrition. Acta Diabetol. 2005;42(4):182–186. doi: 10.1007/s00592-005-0200-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cook A., Burkitt D., McDonald L., Sublett L. Evaluation of glycemic control using NPH insulin sliding scale versus insulin aspart sliding scale in continuously tube-fed patients. Nutr Clin Pract. 2009;24(6):718–722. doi: 10.1177/0884533609351531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hsia E., Seggelke S.A., Gibbs J., Rasouli N., Draznin B. Comparison of 70/30 biphasic insulin with glargine/lispro regimen in non-critically ill diabetic patients on continuous enteral nutrition therapy. Nutr Clin Pract. 2011;26(6):714–717. doi: 10.1177/0884533611420727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Umpierrez G.E. Basal versus sliding-scale regular insulin in hospitalized patients with hyperglycemia during enteral nutrition therapy. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(4):751–753. doi: 10.2337/dc08-2257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gosmanov A.R., Umpierrez G.E. Management of hyperglycemia during enteral and parenteral nutrition therapy. Curr Diab Rep. 2013;13(1):155–162. doi: 10.1007/s11892-012-0335-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McMahon M.M. Management of parenteral nutrition in acutely ill patients with hyperglycemia. Nutr Clin Pract. 2004;19(2):120–128. doi: 10.1177/0115426504019002120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McCowen K.C., Bistrian B.R. Hyperglycemia and nutrition support: theory and practice. Nutr Clin Pract. 2004;19(3):235–244. doi: 10.1177/0115426504019003235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hongsermeier T., Bistrian B.R. Evaluation of a practical technique for determining insulin requirements in diabetic patients receiving total parenteral nutrition. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1993;17(1):16–19. doi: 10.1177/014860719301700116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kennihan M., Zohra T., Devi R., Srinivasan C., Diaz J., Howard B.S. Individualization through standardization: electronic orders for subcutaneous insulin in the hospital. Endocr Pract. 2012;18(6):976–987. doi: 10.4158/EP12107.RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pichardo-Lowden A.R., Fan C.Y., Gabbay R.A. Management of hyperglycemia in the non-intensive care patient: featuring subcutaneous insulin protocols. Endocr Pract. 2011;17(2):249–260. doi: 10.4158/EP10220.RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]