Synopsis

Quality improvement in healthcare is an ongoing challenge. Consideration of the context of the health care system is of tantamount importance. Staff resilience and teamwork climate are key aspects of context that drive quality. Teamwork climate is dynamic, with well-established tools such as TeamSTEPPS available to improve teamwork for specific tasks or global applications. Similarly, burnout and resilience can be modified with interventions such as cultivating gratitude, positivity, and awe. A growing body of literature has shown teamwork and burnout to relate to quality of care, with improved teamwork and decreased burnout expected to produce improved patient quality and safety.

Keywords: safety climate, teamwork, quality, burnout, resilience

Introduction

Improving the quality of health care is a substantial and widespread effort throughout the United States and the world, but patients continue to suffer preventable harm on a daily basis.1 Despite the variability in estimates of preventable deaths (ranging from 25,000 to 250,000 per year in the United States alone), it is clear that mortality from medical error remains a serious problem.2–4 Furthermore, non-fatal medical errors have been found to occur millions of times yearly.1 Adults and children receive recommended care only about half the time,5,6 with premature infants cared for in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) experiencing similar variations in utilization, quality of healthcare, and in clinical outcomes.7–10 For example, health care-associated infection rates,11,12 growth velocity,13 and treatment of persistent pulmonary hypertension14 vary considerably. Up to threefold differences in mortality rates9 and up to 44-fold variation in antibiotic use have been observed among NICUs.15

This observed variation in care is not merely a function of discrete differences in patient risk factors and care process guidelines, but an expression of differences in care contexts, which includes the contribution of each individual as well as the team. High quality health care delivery is inherently reliant on providers maintaining individual excellence and working together effectively as a team. Poor teamwork and communication have been implicated in up to 72% of perinatal deaths and injuries and up to 30% of voluntary error reports.16

Context-sensitive Quality of Care

The current challenges inherent in health care need not serve as discouragement for achieving marked improvement in quality and safety, but emphasize the importance of thinking broadly about creating a context, or environment, that supports quality and safety at the sociopolitical, organizational, mesosystem, microsystem, and team levels as opposed to tackling one problem at a time.1,17,18 Numerous models and frameworks have been proposed to help policy makers, organizational leaders and frontline staff create a context that supports quality and safety.

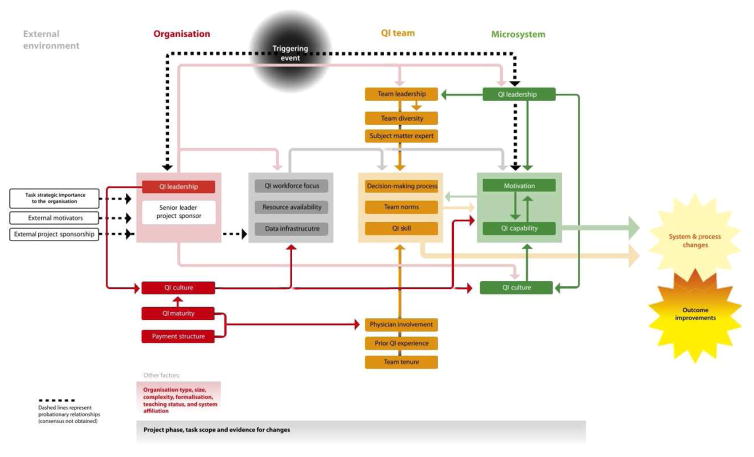

One framework designed to address the role of context in quality and safety is the Model for Understanding Success in Quality (MUSIQ), which describes 25 contextual factors across all levels of the health care system that are likely to influence the success of quality improvement endeavors, shown in Figure 1.19 Although they are interconnected, most of the factors described fall primarily into the realm of microsystem (team members), macrosystem (organizational), or environment (community and society). MUSIQ suggests that the ability to achieve improvements in quality and safety is a result of the supporting context including such factors as organizational and microsystem leadership, data infrastructure, quality improvement culture, resource availability, workforce development, staff capability for QI, and team composition and effectiveness (both the QI team and microsystem “team”).

Figure 1.

Model for Understanding Success in Quality (MUSIQ), showing the contributions of organizational (red), macrosystem (orange), and microsystem (green) factors.

From Kaplan HC, Provost LP, Froehle CM, Margolis PA. The Model for Understanding Success in Quality (MUSIQ): building a theory of context in healthcare quality improvement. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(1):13–20; with permission.

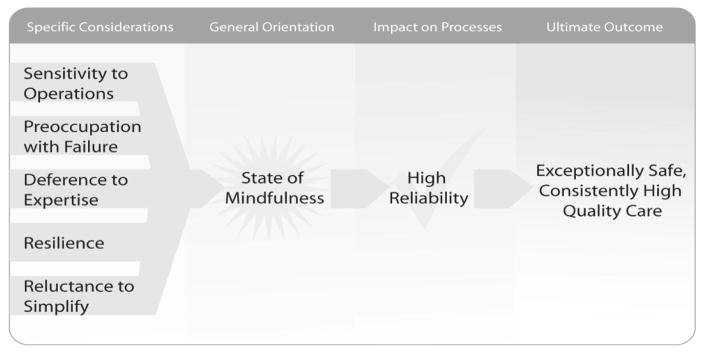

Another framework that highlights the important role of context in safety is the idea of the High Reliability organization (HRO) developed by Weick and Sutcliffe. The HRO concept was originally applied to highly complex and high risk industries including aviation and nuclear power, but the principles are insensitive to the specific field in which they are applied, including in health care. HROs share five core characteristics: Sensitivity to operations, Reluctance to simplify, Preoccupation with failure, Deference to expertise, and Resilience, as illustrated in Figure 2.20 Key contextual factors must be in place for an organization to develop as an HRO, including strong organizational leadership, a culture of safety and teamwork, and resilience, among others.

Figure 2.

The five specific concepts that help create the state of mindfulness needed for a high reliability organization.

From AHRQ Publication No. 08-0022. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. April 2008. Available at: https://archive.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/quality-resources/tools/hroadvice/hroadvice.pdf

Both of these models identify engagement of team members as a key aspect of context supporting quality and safety and the engagement of team members has been described as one of the significant factors predicting success in quality improvement endeavors.21 Common to both models is an emphasis on seemingly intangible feastures of organizational life – the relentless pursuit of better care undergirded by a culture that prizes patient safety. The shared perceptions of leadership and the organizational attitudes toward patient safety and quality improvement reflect the prevailing culture. The culture of safety construct is primarily measured based on health worker perceptions via surveys. The measured domains are called climates, i.e. teamwork climate or safety climate. Climate reflects that perceptions are shared among health workers, meaning that they cluster more strongly within a work unit (e.g. the NICU) than between work units either in the same institution (NICU versus PICU), or work units in other institutions (NICU in hospital A versus NICU in hospital B).22 Two key subfactors of safety culture that affect health worker and patient well-being are teamwork and resilience, which we review in detail.

Teamwork in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit

Across health care, improving teamwork has been recognized as an ongoing challenge. Moving from a “team of experts” to “expert teams” requires skills and training not often provided through traditional education. Paul Schyve, MD, Senior Vice President of the Joint Commission stated, “Our challenge … is not whether we will deliver care in teams but rather how well we will deliver care in teams.”23 Although continually under development and refinement, teamwork measurement and intervention tools have been growing in concert with an increased emphasis on teamwork’s role in health care delivery.

Salas et al have identified seven principal components relevant to teamwork: (1) Cooperation, which is dependent upon mutual trust and team-oriented mindset. (2) Coordination, which requires shared performance monitoring, adaptability, and support. (3) Communication, which must be clear, precise, and timely. (4) Cognition, which refers to a shared understanding of roles and abilities of teammates. (5) Coaching, which refers to team leadership, recognizing the importance of clear expectations. (6) Conflict, the resolution of which is highly dependent on interpersonal skills and a climate of “psychological safety.” (7) Conditions, which refers to the requisite supportive context for teams, as teamwork must be perceived as important to the leadership, and with positive reinforcement for good performance.24,25

Within a health care delivery unit, these factors interplay to create a composite climate of teamwork, which can vary widely across settings. Several tools exist to estimate the teamwork climate of a unit, including the Safety Attitudes Questionnaire (SAQ), Team Emergency Assessment Measure, Fundamental Interpersonal Relations Orientation-Behavior, Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture (HSOPSC), and Team Climate Inventory.26,27 Common to each of these measurement tools is an emphasis on the interpersonal interactions and adaptability of the team members. For example, the teamwork climate scale of the SAQ represents a composite measure of the extent to which caregivers report that they feel supported, can speak up comfortably, can ask questions, feel input is heeded, that conflicts are resolved, and that team members collaborate.28

Profit et al and Sexton et al have reported the SAQ to be valid and useful for assessing individual team work in addition to the overall teamwork climate in the NICU setting.29,30 Similar to other critical care settings,31 physicians in the NICU have been found to have higher perceptions of teamwork than nurses, nurse practitioners, and respiratory care providers.32 Physicians may be in leadership roles more frequently, resulting in the potential to elevate the physician’s own perspective of adequate teamwork, when, in fact, teamwork climate is weak in a given setting. It is unclear whether this difference is secondary to personal characteristics, professional responsibilities, or other unmeasured factors, but it has implications for the overall functioning of the NICU. Personal attributes, reputation, expertise, and seniority have been found to affect the ability of critical care providers to work together effectively.31

Neither individual teamwork perception nor teamwork climate are static, however. Interventions focused on improving the teamwork of a health care unit include generalized training courses such as crew resource management,33,34 task-specific training,35,36 or the implementation of process checklists.37 A meta-analysis of ninety-three team training interventions demonstrated consistent moderate improvements in teamwork measures, with more pronounced benefits seen following training programs combining generalized and task-specific approaches.38 Within pediatric residency training, Thomas et al have reported that randomization to a teamwork-based neonatal resuscitation curriculum results in up to threefold higher utilization of teamwork behaviors among interns when compared to standard training,35 and that benefits can persist for at least 6 months.36

Across NICUs, teamwork climate has been found to vary widely.32 Providing excellent care consistently throughout the clinical spectrum, from routine rounds to high intensity resuscitations, rely on the adaptability of team members. NICUs with low teamwork climate may struggle to anticipate or adapt to changing clinical needs. Yet, teamwork is a malleable construct and interventions to improve teamwork are available. While many of the teamwork interventions with measurable benefits reported in the published literature have focused on task-specific training for particular situations such as surgical procedures or neonatal resuscitation, the same teamwork principles have relevance for all forms of neonatal health care delivery. Although the benefits are more challenging to quantify, system-wide generalized training may support teamwork within NICUs to a greater extent than task-specific training.33

To target system-wide benefit, The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality has developed a teamwork tool kit in conjunction with the United States Department of Defense. Named “Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety” (TeamSTEPPS), the intervention includes assessment, training, and sustainment phases focused on four core competencies: (1) Team leadership, (2) Situation monitoring, (3) Mutual support, and (4) Communication.39 This approach has been used in multiple health care settings,40,41 including one reported intervention which included NICU providers and demonstrated an improvement in perceptions of teamwork.42 Despite the heterogeneity of personal contributions, individual teamwork perception and teamwork climate are inextricably linked. The growing body of evidence regarding the ability to improve teamwork climate lends support for improved teamwork as a critical target of quality improvement initiatives.

Burnout and Resilience in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit

Another key contextual factor that may influence quality of care is provider burnout. Burnout describes a condition of fatigue, detachment, and cynicism resulting from prolonged high levels of stress.43 In the critical care setting, burnout rates are likely driven predominantly by high workload, frequent changes in technology and guidelines, endeavors for high-quality care, and emotional challenges of dealing with critically ill patients and their families.44–47 Burnout affects 27–86% of health care workers,48–51 with over half of physicians reporting moderate burnout52 and around one-third of nurses and physicians meeting criteria for severe burnout.48,53 The most commonly used instrument to measure burnout is the Maslach Burnout Inventory,54 portions of which have been validated in multiple settings, including labor and delivery units and the NICU.30,55 The emotional exhaustion subset has been used in isolation to provide a rapid assessment of an individual’s burnout, consisting of 4 prompts: (1) I feel fatigued when I get up in the morning and have to face another day on the job, (2) I feel burned out from my work, (3) I feel frustrated by my job, and (4) I feel I am working too hard on my job.51 Responses to these questions which cluster in the neutral or affirmative range have been used as a marker for burnout.43

In contrast to burnout, resilience has been defined as a combination of characteristics that interact dynamically to allow an individual to bounce back, cope successfully and function above the norm in spite of significant stress or adversity.43,56 Resilience has primarily been measured in the context of burnout avoidance. However, several key characteristics have been identified as directly contributing to resilience in qualitative research. These characteristics include optimism, adaptability, initiative, tolerance, organizational skills, being a team worker, keeping within professional boundaries, assertiveness, humor, and a sense of self-worth.56

Although often expressed as separate entities, the interpersonal aspects of resilience and teamwork are closely linked. Many of the characteristics identified as contributory to personal resilience are conceptually linked to those promoting a positive teamwork climate. Profit et al have reported a negative association between burnout and teamwork climate among a large cohort of NICU providers, with the strongest association seen among providers reporting high levels of job frustration.43 In the same study, the proportion of NICU providers reporting low or very low burnout symptoms, calculated as the resilient proportion, was found to be significantly associated with several domains relevant to quality. Strong correlation coefficients with teamwork climate (0.60), job satisfaction (0.65), safety climate (0.51), perceptions of management (0.61), and working conditions (0.53) were all highly significant.43 A similar association has been observed in the pediatric intensive care unit, with Lee et al describing a 7% increase in teamwork climate perception among providers with moderately high or high resilience scores.57

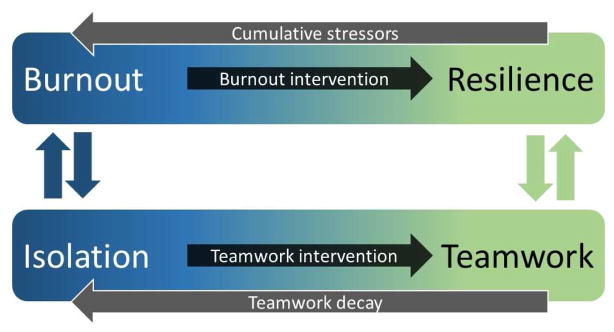

The specific individual characteristics expected to drive these associations include adaptability, organizational skills, and a team-focused mindset, as these each carry profound implications for team functioning. Each individual’s daily experience is an amalgamation of interactions which can each have positive or negative effects, creating a cumulative tide which may become substantial when taken in sum. Compared to smooth and coordinated interactions, effortful and inefficient interactions have been found to reduce self-regulation and performance on subsequent tasks.58 As illustrated in Figure 3, burned out individuals may be more prone to isolation, as they may experience negative experiences with teamwork secondary to challenging interpersonal interactions. These negative interactions then drive further isolation and result in a positive feedback loop, resulting in escalating levels of burnout. Downward spirals in teamwork can have serious consequences; for example, nurses who reported a serious lack of good teamwork had a five-fold risk for intending to leave the profession.59

Figure 3.

Relationship of the burnout-resiliency continuum to the isolation-teamwork continuum. Burnout requires active intervention to achieve resilience, but can regress as the result of cumulative stressors. Similarly, isolation can be transformed to teamwork with interventions, but is prone to decay over time. Burned out individuals demonstrate reciprocity with isolated climates, but a positive teamwork climate can positively feedback with resilience through affirmative interactions

However, the converse also follows, with individuals exhibiting higher resilience more prone to positive teamwork interactions, which in turn feed back to further improved resilience.60 A qualitative study found that newly graduated nurses highlighted the importance of having nourishing interactions and good teamwork as integral to building workplace belongingness and staff empowerment.61 The effects of better teamwork for resilience is just part of a large, overarching body of evidence that social connectedness significantly predicts better mental and physical well-being, and even lower rates of mortality.62

Burnout is a reversible condition, and resilience can be coached. Several strategies have been developed to combat burnout and promote resilience relevant to the health care setting. However, these strategies, such as mindfulness practice, are often time-consuming and pragmatically challenging to administer.63–66 Brief, widely distributable burnout interventions based on mindfulness strategies are currently being prospectively evaluated in multiple settings, including the NICU, with good benefit seen in pilot studies. The interventions focus on expressing thankfulness (Gratitude), dwelling on positive events (Three Good Things), structured cultivation of awe and wonder (Awe), random acts of kindness, identifying personal gifts (Signature Strengths), and relationship resilience. Profit and Sexton have combined these interventions into a “bite-sized” resilience program called Web-based Implementation of the Science for Enhancing Resilience (WISER), which is funded by the National Institute of Health for testing.

Teamwork- and Resilience-Driven Quality Improvement

Conceptually, it follows that improvements in teamwork climate and individual resilience can be expected to significantly contribute to improved quality of care. A single-center study by Rahn et al reported a negative association between nursing teamwork and unassisted patient falls on a medical/surgical unit.67 Within the NICU setting, teamwork has been negatively associated with health care-associated infections among a diverse cohort of California NICUs, such that the odds of an infant contracting an infection decreased by 18% with each 10% rise in NICU survey respondents reporting good teamwork.68

Conversely, improvements in teamwork have been associated with reduced medication errors, decreased health care-associated infections,69,70 and higher quality newborn resuscitation.35 Neily et al reported an 18% reduction in surgical mortality following implementation of team-based surgical checklists at Veteran’s Affairs hospitals.71 In Michigan intensive care units, Pronovost et al reported an 80% reduction in catheter-related bloodstream infections with the simultaneous introduction of a teamwork/unit safety intervention and an infection prevention intervention.69,70

The association between provider resilience and quality of care has been largely unreported, but there is an increasing body of literature regarding burnout in relation to quality measures. A meta-analysis by Salyers et al evaluated eighty-two studies and reported a small to moderate negative association between provider burnout and quality of care measures, with 7% of quality measure variance and 5% of safety measure variance attributed to provider burnout.72 Notably, Aiken et al have reported an observed 7% increase in patient mortality and 23% increase in the odds of nurse burnout for each additional patient added to a nurse’s workload.73 Expounding on this work in multivariable analyses, Cimiotti et al. reported that burnout carries a stronger association with health care-associated infections than does nurse staffing, with each 10% increase in burnout prevalence corresponding to 0.8 urinary tract infections and 1.6 surgical site infections per 1000 patients.74 Specific to neonatology, Tawfik et al reported a moderate correlation (r=0.34) between health care worker burnout and increased rates of health care-associated infections among very low birthweight infants in high-volume NICUs in California, which was most pronounced among providers reporting feeling fatigued or overworked.51

It remains to be proven that longitudinal increases in resilience can result in observable improvements in quality of care. However, the strength of associations repeatedly observed between high burnout and adverse events suggest that this domain of the quality microclimate is an appropriate target for quality improvement endeavors.

Conclusions

With the continued increasing recognition of the need for quality improvement in health care, consideration of the context of the health care delivery system is of tantamount importance. Aspects of context including teamwork climate and personal resilience are important factors in achieving optimal quality and safety outcomes and efforts to modify these aspects of context (e.g., improve teamwork climate, build staff resilience) are a key quality improvement strategy. There are well-established tools such as TeamSTEPPS which are available to improve teamwork for specific tasks or global applications. Similarly, burnout and by extension, resilience, can be modified with specific interventions such as cultivating gratitude, positivity, and awe. A growing body of literature has shown teamwork and burnout to relate to quality of care, with improved teamwork and decreased burnout expected to produce improved patient quality and safety metrics.

Key Points.

Wide variation in NICU quality of care exists, with differences in part attributable to variation in care context.

Teamwork is an important driver of health care quality, and can be improved with tools such as TeamSTEPPS.

Individual resilience is a key contextual factor that may affect health care quality directly and indirectly via teamwork, and it can be coached.

Improvements in teamwork and resilience are expected to enhance health care quality improvement initiatives.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development [R01 HD084679-01, Co-PI: Sexton and Profit] and the Jackson Vaughan Critical Care Research Fund.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Chassin MR, Loeb JM. High-reliability health care: getting there from here. Milbank Q. 2013;91(3):459–490. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Makary MA, Daniel M. Medical error-the third leading cause of death in the US. BMJ. 2016;353:i2139. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shojania KG, Dixon-Woods M. Estimating deaths due to medical error: the ongoing controversy and why it matters. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016 doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2016-006144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mangione-Smith R, DeCristofaro AH, Setodji CM, et al. The quality of care received by children and adolescents in the United States. Pediatric Academic Societies’ Annual Meeting. 2006;59:4550–4551. [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;348(26):2635–2645. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa022615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horbar JD, Badger GJ, Lewit EM, Rogowski J, Shiono PH. Hospital and patient characteristics associated with variation in 28-day mortality rates for very low birth weight infants. Vermont Oxford Network. Pediatrics. 1997;99(2):149–156. doi: 10.1542/peds.99.2.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sankaran K, Chien L-Y, Walker R, Seshia M, Ohlsson A, Lee SK. Variations in mortality rates among Canadian neonatal intensive care units. Cmaj. 2002;166(2):173–178. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rogowski JA, Staiger DO, Horbar JD. Variations in the quality of care for very-low-birthweight infants: implications for policy. Health Aff. 2004;23(5):88–97. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.5.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phibbs CS, Baker LC, Caughey AB, Danielsen B, Schmitt SK, Phibbs RH. Level and volume of neonatal intensive care and mortality in very-low-birth-weight infants. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(21):2165–2175. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa065029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brodie SB, Sands KE, Gray JE, et al. Occurrence of nosocomial bloodstream infections in six neonatal intensive care units. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19(1):56–65. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200001000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stoll BJ, Hansen N, Fanaroff AA, et al. Late-onset sepsis in very low birth weight neonates: the experience of the NICHD neonatal research network. Pediatrics. 2002;110(2):285–291. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.2.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olsen IE, Richardson DK, Schmid CH, Ausman LM, Dwyer JT. Intersite differences in weight growth velocity of extremely premature infants. Pediatrics. 2002;110:1125–1132. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.6.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walsh-Sukys MC, Tyson JE, Wright LL, et al. Persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn in the era before nitric oxide: practice variation and outcomes. Pediatrics. 2000;105(1):14–20. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schulman J, Dimand RJ, Lee HC, Duenas GV, Bennett MV, Gould JB. Neonatal intensive care unit antibiotic use. Pediatrics. 2015;135(5):826–833. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suresh G, Horbar JD, Plsek P, et al. Voluntary anonymous reporting of medical errors for neonatal intensive care. Pediatrics. 2004;113(6):1609–1618. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.6.1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Spall H, Kassam A, Tollefson TT. Near-misses are an opportunity to improve patient safety: adapting strategies of high reliability organizations to healthcare. Current opinion in otolaryngology & head and neck surgery. 2015;23(4):292–296. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0000000000000177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sutcliffe KM, Paine L, Pronovost PJ. Re-examining high reliability: actively organising for safety. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016 doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaplan HC, Provost LP, Froehle CM, Margolis PA. The Model for Understanding Success in Quality (MUSIQ): building a theory of context in healthcare quality improvement. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(1):13–20. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chassin MR, Loeb JM. The ongoing quality improvement journey: next stop, high reliability. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30(4):559–568. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaplan HC, Froehle CM, Cassedy A, Provost LP, Margolis PA. An exploratory analysis of the model for understanding success in quality. Health care management review. 2013;38(4):325–338. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0b013e3182689772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vogus TJ. Safety climate strength: a promising construct for safety research and practice. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(9):649–652. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schyve PM. Teamwork--the changing nature of professional competence. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2005;31(4):183–184. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(05)31024-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salas E, Rosen MA. Building high reliability teams: progress and some reflections on teamwork training. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(5):369–373. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salas E, Almeida SA, Salisbury M, et al. What are the critical success factors for team training in health care? Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2009;35(8):398–405. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(09)35056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cooper S. Teamwork: What should we measure and how should we measure it? International emergency nursing. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.ienj.2016.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones KJ, Skinner A, Xu L, Sun J, Mueller K. The AHRQ Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture: A Tool to Plan and Evaluate Patient Safety Programs. In: Henriksen K, Battles JB, Keyes MA, Grady ML, editors. Advances in Patient Safety: New Directions and Alternative Approaches (Vol. 2: Culture and Redesign) Rockville (MD): 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sexton JB, Helmreich RL, Neilands TB, et al. The Safety Attitudes Questionnaire: psychometric properties, benchmarking data, and emerging research. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:44. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-6-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Profit J, Etchegaray J, Petersen LA, et al. The Safety Attitudes Questionnaire as a tool for benchmarking safety culture in the NICU. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2012;97(2):F127–132. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2011-300612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sexton JB, Sharek PJ, Thomas EJ, et al. Exposure to Leadership WalkRounds in neonatal intensive care units is associated with a better patient safety culture and less caregiver burnout. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(10):814–822. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomas EJ, Sexton JB, Helmreich RL. Discrepant attitudes about teamwork among critical care nurses and physicians. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(3):956–959. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000056183.89175.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Profit J, Etchegaray J, Petersen LA, et al. Neonatal intensive care unit safety culture varies widely. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2012;97(2):F120–126. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2011-300635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomas EJ. Improving teamwork in healthcare: current approaches and the path forward. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20(8):647–650. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lerner S, Magrane D, Friedman E. Teaching teamwork in medical education. Mt Sinai J Med. 2009;76(4):318–329. doi: 10.1002/msj.20129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomas EJ, Taggart B, Crandell S, et al. Teaching teamwork during the Neonatal Resuscitation Program: a randomized trial. JPerinatol. 2007;27(7):409–414. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thomas EJ, Williams AL, Reichman EF, Lasky RE, Crandell S, Taggart WR. Team training in the neonatal resuscitation program for interns: teamwork and quality of resuscitations. Pediatrics. 2010;125(3):539–546. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thomas EJ, Sexton JB, Helmreich RL. Translating teamwork behaviours from aviation to healthcare: development of behavioural markers for neonatal resuscitation. Quality & safety in health care. 2004;13(Suppl 1):i57–64. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2004.009811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salas E, DiazGranados D, Klein C, et al. Does team training improve team performance? A meta-analysis. Hum Factors. 2008;50(6):903–933. doi: 10.1518/001872008X375009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Clancy CM, Tornberg DN. TeamSTEPPS: assuring optimal teamwork in clinical settings. Am J Med Qual. 2007;22(3):214–217. doi: 10.1177/1062860607300616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mayer CM, Cluff L, Lin WT, et al. Evaluating efforts to optimize TeamSTEPPS implementation in surgical and pediatric intensive care units. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2011;37(8):365–374. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(11)37047-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sawyer T, Laubach VA, Hudak J, Yamamura K, Pocrnich A. Improvements in teamwork during neonatal resuscitation after interprofessional TeamSTEPPS training. Neonatal Netw. 2013;32(1):26–33. doi: 10.1891/0730-0832.32.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beitlich P. TeamSTEPPS implementation in the LD/NICU settings. Nurs Manage. 2015;46(6):15–18. doi: 10.1097/01.NUMA.0000465404.30709.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Profit J, Sharek PJ, Amspoker AB, et al. Burnout in the NICU setting and its relation to safety culture. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(10):806–813. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2014-002831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Braithwaite M. Nurse burnout and stress in the NICU. Adv Neonatal Care. 2008;8(6):343–347. doi: 10.1097/01.ANC.0000342767.17606.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rochefort CM, Clarke SP. Nurses’ work environments, care rationing, job outcomes, and quality of care on neonatal units. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66(10):2213–2224. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Mol MM, Kompanje EJ, Benoit DD, Bakker J, Nijkamp MD. The Prevalence of Compassion Fatigue and Burnout among Healthcare Professionals in Intensive Care Units: A Systematic Review. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0136955. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Portoghese I, Galletta M, Coppola RC, Finco G, Campagna M. Burnout and workload among health care workers: the moderating role of job control. Saf Health Work. 2014;5(3):152–157. doi: 10.1016/j.shaw.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shanafelt TD, West CP, Sloan JA, et al. Career fit and burnout among academic faculty. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(10):990–995. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mealer M, Burnham EL, Goode CJ, Rothbaum B, Moss M. The prevalence and impact of post traumatic stress disorder and burnout syndrome in nurses. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26(12):1118–1126. doi: 10.1002/da.20631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thomas EJ, Sherwood GD, Mulhollem JL, Sexton JB, Helmreich RL. Working together in the neonatal intensive care unit: provider perspectives. J Perinatol. 2004;24(9):552–559. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tawfik DS, Sexton JB, Kan P, et al. Burnout in the neonatal intensive care unit and its relation to healthcare-associated infections. J Perinatol. 2016 doi: 10.1038/jp.2016.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in Burnout and Satisfaction With Work-Life Balance in Physicians and the General US Working Population Between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600–1613. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bellieni CV, Righetti P, Ciampa R, Iacoponi F, Coviello C, Buonocore G. Assessing burnout among neonatologists. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25(10):2130–2134. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2012.666590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Maslach C, Jackson SE. Maslach Burnout Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press, Inc; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Block M, Ehrenworth JF, Cuce VM, et al. Measuring handoff quality in labor and delivery: development, validation, and application of the Coordination of Handoff Effectiveness Questionnaire (CHEQ) Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2013;39(5):213–220. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(13)39028-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Matheson C, Robertson HD, Elliott AM, Iversen L, Murchie P. Resilience of primary healthcare professionals working in challenging environments: a focus group study. The British journal of general practice: the journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners. 2016;66(648):e507–515. doi: 10.3399/bjgp16X685285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee KJ, Forbes ML, Lukasiewicz GJ, et al. Promoting Staff Resilience in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit. American journal of critical care: an official publication, American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. 2015;24(5):422–430. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2015720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Finkel EJ, Campbell WK, Brunell AB, Dalton AN, Scarbeck SJ, Chartrand TL. High-maintenance interaction: inefficient social coordination impairs self-regulation. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2006;91(3):456–475. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.3.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Estryn-Behar M, Van der Heijden BI, Oginska H, et al. The impact of social work environment, teamwork characteristics, burnout, and personal factors upon intent to leave among European nurses. Med Care. 2007;45(10):939–950. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31806728d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wahlin I, Ek AC, Idvall E. Staff empowerment in intensive care: nurses’ and physicians’ lived experiences. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2010;26(5):262–269. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cleary M, Horsfall J, Mannix J, O’Hara-Aarons M, Jackson D. Valuing teamwork: Insights from newly-registered nurses working in specialist mental health services. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2011;20(6):454–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2011.00752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Umberson D, Montez JK. Social relationships and health: a flashpoint for health policy. J Health Soc Behav. 2010;51(Suppl):S54–66. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Rabatin JT, et al. Intervention to promote physician well-being, job satisfaction, and professionalism: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):527–533. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.14387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rowe MM. Teaching health-care providers coping: results of a two-year study. J Behav Med. 1999;22(5):511–527. doi: 10.1023/a:1018661508593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, Shanafelt TD. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31279-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Westermann C, Kozak A, Harling M, Nienhaus A. Burnout intervention studies for inpatient elderly care nursing staff: systematic literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2014;51(1):63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rahn DJ. Transformational Teamwork: Exploring the Impact of Nursing Teamwork on Nurse-Sensitive Quality Indicators. J Nurs Care Qual. 2016;31(3):262–268. doi: 10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Profit J, Sharek PJ, Bennett M, et al. Teamwork in the NICU Setting and Its Association with Healthcare-associated Infections in Very Low Birth Weight Infants. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1601563. Under Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pronovost P, Needham D, Berenholtz S, et al. An intervention to decrease catheter-related bloodstream infections in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(26):2725–2732. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pronovost PJ, Berenholtz SM, Goeschel C, et al. Improving patient safety in intensive care units in Michigan. J Crit Care. 2008;23(2):207–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Neily J, Mills PD, Young-Xu Y, et al. Association between implementation of a medical team training program and surgical mortality. JAMA. 2010;304(15):1693–1700. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Salyers MP, Bonfils KA, Luther L, et al. The Relationship Between Professional Burnout and Quality and Safety in Healthcare: A Meta-Analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3886-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Sochalski J, Silber JH. Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction. JAMA. 2002;288(16):1987–1993. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.16.1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cimiotti JP, Aiken LH, Sloane DM, Wu ES. Nurse staffing, burnout, and health care-associated infection. Am J Infect Control. 2012;40(6):486–490. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2012.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]