Abstract

Osteosarcomas are the most abundant form of bone malignancies in multiple species. Canine osteosarcomas are considered a valuable model for human osteosarcomas because of their similar features. Feline osteosarcomas, on the other hand, are rarely studied but have interesting characteristics, such as a better survival prognosis than dogs or humans, and less likelihood of metastasis. To enable experimental approaches to study these differences we have established five new canine osteosarcoma cell lines out of three tumors, COS_1186h, COS_1186w, COS_1189, and COS_1220, one osteosarcoma-derived lung metastasis, COS_1033, and two new feline osteosarcoma cell lines, FOS_1077 and FOS_1140. Their osteogenic and neoplastic origin, as well as their potential to produce calcified structures, was determined by the markers osteocalcin, osteonectin, tissue unspecific alkaline phosphatase, p53, cytokeratin, vimentin, and alizarin red. The newly developed cell lines retained most of their markers in vitro but only spontaneously formed spheroids produced by COS_1189 showed calcification in vitro.

Keywords: osteosarcoma, cell culture, dog, cat

1. Introduction

Tumors are one of the major diseases in both human and companion animals with an annual incidence rate of about 182/100,000 in humans [1] 381/100,000 in dogs and 156/100,000 of cats [2]. When comparing numerical data between human and veterinary patients it has to be considered that a number of unrecorded cases are present in animal patients, in particular in the feline species. It is, therefore, of major clinical importance to investigate issues such as tumor progression and metastasis behavior, the main reason for tumor related death, and to test tumor cells for drug response. For ethical reasons, in vitro methods are preferable whenever possible over experiments on living animals. A suitable method for experimental approaches, especially drug tests in cancer research, is the use of cell cultures. Due to of the natural immortality of tumor cells, they retain their in vivo features better than normal cells which have to be artificially immortalized to be used for longer periods of time [3,4,5].

Osteosarcoma is the most common neoplasm of the bone in human patients, cats, and dogs, and it is generally assumed that it derives from osteoblastic cells, but now pluripotent stem cells have also been under discussion as a source of neoplastic cells [6,7,8]. Due to the many similarities between human and canine osteosarcomas, the latter is considered a valuable model organism for this disease [9,10]. These similarities include the sites most often affected, a predominance of male sex, and the high likelihood of metastasis development, preferably to the lung [10]. Due to the generally late diagnosis of the disease, micrometastases are often already present at the time of diagnosis [11]. However, there are also noteworthy differences between osteosarcomas of the two species, like the age of onset; generally, adolescence in humans—although there is a notable second peak in patients >60 years [12]—and middle-aged to older dogs are affected [13]. It also seems that human osteosarcoma is caused by growth during adolescence [14,15], while the older age of onset in canines has been supposed to be induced by mechanical forces, such as (micro-) fractures [16].

A number of cell lines have successfully been cultivated and characterized from human [11,16,17,18,19] and canine [20,21] osteosarcomas. While a large number of human osteosarcoma cell lines are commercially available, like HOS [22], U2 OS [23], Saos-2 [24], or MG-63 [25], only the canine osteosarcoma cell line D-17 (CCL-183) [26] is accessible for scientists. Feline osteosarcomas, on the other hand, were rarely studied, and to our knowledge this work presents the first establishment and description of a feline osteosarcoma cell line. Despite this, we believe feline osteosarcoma to be a valuable model in understanding osteosarcoma tumor mechanisms. While feline osteosarcomas have a strong histological similarity to human and canine osteosarcomas [27], their behavior in tumor progression, especially the much lower rate of metastases [28], stands opposed to their human and canine counterparts.

The aim of the present study was the isolation and cultivation of primary cells from different types of canine and feline osteosarcomas. The cell cultures were tested for bone tumor markers as determined before, such as tissue unspecific alkaline phosphatase [29,30], osteocalcin [31], and osteonectin [19,20,32,33]. The deposition of calcified structures was assessed by alizarin red staining [34]. Cultivated osteosarcoma cells were further characterized immunohistochemically for vimentin [20,32,33] and cytokeratin intermediate filaments [32] and the tumor-suppressor p53 [33]. All of the above-mentioned factors were comparatively stained on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) sections of the corresponding tumor tissue. Furthermore, the origin of cells from the respective tumor was verified by DNA fingerprinting.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Animals

Osteosarcoma tumor samples from dogs (n = 4) and cats (n = 2) were collected after therapeutic limb amputation or euthanasia. The study was approved by the Ethical and Animal Welfare Committee of the University of Veterinary Medicine (15 December 2014) and conducted according to the guidelines of the local ethical committee. Animal data and tumor subtypes are reported in Table 1. Tumor tissues were transferred under sterile conditions to the VetBiobank of the VetCore Facility for Research of the University of Veterinary Medicine, Vienna. Tumors were dissected and aliquots of tumor tissue were formaldehyde-fixed and paraffin-embedded or shock frozen in liquid nitrogen with and without RNAlater (Life Technologies, Vienna, Austria) for RNA and DNA analysis. Before embedding in paraffin, strongly calcified samples were decalcified in 8% EDTA before the embedding process. Further parts of the tumors were used for cell culture experiments.

Table 1.

Animals used for the creation of the new cell lines.

| Sample | Resulting Cell Line | Species | Sex a | Age | Breed | OS Subtype | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1033 | COS_1033 | Dog | F | 7y 1m | Boxer | Teleangiectatic OS with giant cell participation | Lung metastasis |

| 1077 | FOS_1077 | Cat | F | 10y | Domestic shorthair | FibroblasticOS | Costa |

| 1140 | FOS_1140 | Cat | M ° | n/s | Domestic shorthair | Osteoblastic OS | Tibia |

| 1186 | COS_1186w COS_1186h | Dog | M ° | 11y 2m | Dachshund | Osteoblastic OS | Scapula |

| 1189 | COS_1189 | Dog | M ° | 7y 3m | Mixed breed | Poorly defined OS/ signs of osteo-or synovialsarkom | Humerus |

| 1220 | COS_1220 | Dog | F ° | 5y 3m | Boxer | Fibroblastic OS | Radius |

a F = female, M = male, ° = neutered; n/s = not specified.

2.2. Cell Culture

Pieces of fresh tumor tissue were cut into cubes of about 1 mm3. The pieces were washed three times in DPBS (Sigma Aldrich, Vienna, Austria) to remove erythrocytes and then transferred to individual wells of a four-well plate (Thermo Fischer Scientific Vienna, Austria) with either DMEM (Sigma Aldrich) or Q286 medium (GE-Healthcare, Munich, Germany), supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS, Sigma-Aldrich), 625 pg/100 mL Amphotericin B (Bio and Sell, Feucht, Germany), 2 nm L-glutamine (Biochrom, Berlin, Germany), and 1% Pen/Strep/Fungi Mix (10,000 U Penicilin; 10 mg Streptomycin; 25 µg Amphotericin B/mL, Bio and Sell), or the complete osteoblast growth medium (OGM BulletKit; Szabo Scandic, Vienna, Austria). Cells were incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2. The first medium change was done after 24 h; after that, medium was changed in two day intervals. When cells started to grow out from the tissue pieces and attached to the plastic surface of the cell culture dish, the tissue pieces were detached mechanically from the plastic surface with a pipette tip to generate new spawning points within the well. At near-confluency, cells were trypsinized (Trypsin/EDTA solution, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and transferred to six-well plates (Sarstedt, Nümbrecht, Germany). After reaching near-confluency in the six-well plate, cells were transferred to 25 cm2 cell culture flasks (Sarstedt) and expanded in 25 cm2 and 75 cm2 cell culture flasks (Sarstedt). Cells were frozen as soon as two 25-cm2 cell culture flasks reached 80% confluency each, by resuspending trypsinized cells in a 1.5 M DMSO supplemented medium and using a CoolCell (Biozym, Vienna, Austria) to bring samples to −80 °C at a controlled cooling rate before storing them in liquid nitrogen.

For histological purposes, cells were scraped off a 25 cm2 flask, at about 80% confluency and fixed in 4% buffered formaldehyde overnight. The cells were then pelleted by centrifugation (5000 g for 2 min) and the cell pellets pre-embedded in Histogel™ (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Vienna, Austria) and, subsequently, paraffin embedded.

2.3. Histology

FFPE samples from original tumor tissue and pellets of cell cultures were used for histological analysis. Sections measuring 3 µm were mounted on glutaraldehyde-activated 3-aminopropyl-triethoxysilane (APES)-coated glass slides.

2.4. Immunohistochemistry

A summary of the techniques and antibodies used in immunohistochemistry can be found in Table 2. For tissue unspecific alkaline phosphatase endogenous peroxidases were blocked using 0.6% H2O2 in 80% methanol. Epitope retrieval for tissue and cell pellets was done by steaming or microwaving as indicated in Table 2. 1.5% normal goat serum (Dako) was used for protein blocking. Sections/coverslip cultures were incubated with the respective primary antibody over night at 4 °C. For osteonectin, osteocalcin, vimentin, and cytokeratin, Alexa Fluor 488 goat-anti-mouse IgG (H + L) highly cross-adsorbed (Life Technologies; dilution 1:100 in PBS) was used as the secondary antibody. DAPI (Sigma Aldrich) was used for nuclear staining. The BrightVision Poly-HRP-anti-rabbit (ImmunoLogic, Duiven, Netherlands) was used as the secondary antibody for alkaline phosphatase and p53 staining, and slides were counterstained with haematoxylin. Sections prepared without primary antibody served as negative controls. For tissue unspecific alkaline phosphatase, osteocalcin canine phalanx and joint sections and feline femur sections were used as controls. Canine uterus was used as a control for vimentin and cytokeratin.

Table 2.

Details of procedures used for IHC staining.

| Primary Antibody | Clone | Dilution | Antigen Retrieval | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Osteopontin | polyclonal | 1:75 | Tissue | 30 min steamed in citric acid buffer pH 6.0 |

Biogenesis, Poole, UK |

| rabbit | Cell pellet | 2x 5 min microwaved in citric acid buffer pH 6.0 |

|||

| Osteocalcin | polyclonal | 1:400 | Tissue | 30 min steamed in citric acid buffer pH 6.0 |

Biogenesis |

| rabbit | Cell pellet | 2x 5 min microwaved in citric acid buffer pH 6.0 |

|||

| Cytokeratin | monoclonal | 1:250 | Tissue | 30 min steamed in Tris-EDTA buffer pH 9.0 |

Cell Marque, Rocklin, CA, USA |

| mouse | Cell pellet | 2x 5 min microwaved in Tris-EDTA buffer pH 9.0 |

|||

| Vimentin | monoclonal | 1:200 | Tissue | 20 min steamed in citric acid buffer pH 6.0 |

Dako, Glostrup, Denmark |

| mouse | Cell pellet | 2x 5 min microwaved in citric acid buffer pH 6.0 |

|||

| Alkaline Phosphatase | polyclonal | Dog: 1:100 | Tissue | 30 min steamed in citric acid buffer pH 6.0 |

Genetex, Irvine, CA, USA |

| rabbit | Cat: 1:250 | Cell pellet | 2x 5 min microwaved in citric acid buffer pH 6.0 |

||

| Osteonectin | polyclonal | 1:1500 | Tissue | none | Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA |

| rabbit | Cell pellet | none | |||

| p53 | monoclonal | 1:90 | Tissue | 3x 5 min microwaved in Tris-EDTA buffer pH 9.0 |

Enzo Life Sciences, Lausen, Switzerland |

| mouse | Cell pellet | 2x 5 min microwaved in Tris-EDTA buffer pH 9.0 |

|||

To determine a potential calcification of cultured osteosarcoma cells, slides of cell culture pellets and tumor were stained for 1 h in alizarin red (Morphisto, Frankfurt, Germany) pH 9.0 and 5 min alizarin red pH 7.0 (Morphisto).

2.5. PCR

To verify the presence of ostecalcin (BGLAP), osteonectin (SPARC), and tissue unspecific alkaline phosphatase (ALPL), an mRNA amplicon dissociation assay was used. RNA was isolated from cells and corresponding tumours using the miRNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and the RNeasy Fibrous Tissue Mini kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, respectively. The amount of 500 ng RNA was transcribed into cDNA using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The reaction volume of 20 µl contained 2 µL 10 × RT Buffer, 0.8 µL 25 × dNTP Mix (100 mM of each dNTP), 2 µL 10 × RT random primers, 50 U multiscribe reverse transcriptase and 14.2 µL of RNase-free H2O containing the 500 ng of RNA. The reaction was incubated for 10 min at 25 °C to initiate primer binding and was followed by 2 h at 37°C for transcription. The reaction was stopped by heating to 85 °C for 5 s.

For PCR 5 ng of cDNA was mixed with 1 µL buffer BD (Solis Biodyne, Tartu, Estonia) 3.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM of each dNTP (Solis Biodyne) 0.4 × EvaGreen (Biotium, Hayward, CA, USA), 200 nM of each primer (Sigma-Aldrich) 0.5 unit hot-start Taq DNA polymerase (HOT FIREPol® DNA polymerase; Solis Biodyne) in a 10 µL reaction volume. Cycling conditions consisted of a hot start at 95 °C for 15 min followed by 40 cycles of denaturation for 15 s at 95 °C, annealing for 20 s at 60 °C and elongation for 20 s at 72 °C. For analysis a melting curve analysis was performed after the PCR, were the reaction mixture was heated from 60 °C to 95 °C at a ramp rate of 0.03 °C/s acquiring 20 data points per °C (primer sequences are given in Table 3).

Table 3.

PCR-primer and assay details.

| Gene / Symbol | Species | NCBI Ref Nr (Dog/Cat) | Foward Primer | Reverse Primer | Length (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Osteocalcin / | Dog | XM_547536.4 | GCTGGTCCAGCAGATGCAA | CCCAGCCCAGAGTCCAGGTA | 125 |

| BGLAP | Cat | XM_003999711.3 | GCCCGGCAGATGCAAAG | CCCTCCTGCTTGGACACGA | 70 |

| Osteopontin/ | Dog | XM_003434023.2 | ACTGACATTCCAGCAACCCAA | CACAAGTGATGTGAAGTCCTCCTCT | 168 |

| SPP1 | Cat | XM_006930977.2 | CAATTTTTCACCCCAGCTGTC | CACAAGTGATGTGAAGTCCTCCTCT | 150 |

| Osteonectin / | Dog | XM_005619272.1 | CACCCTGGAAGGCACCAA | CGCAGAGGGAATTCAGTCAGC | 108 |

| SPARC | Cat | XM_003981374.3 | CCAAGAAGGGCCACAAACTC | GGAATTCGGTCAGCTCGGA | 87 |

| Alkaline phosphatase / | Dog | XM_005617214.1 | GGCCTGAACCTCATCGACAT | GCGGTTCCAGACGTAGTGAGA | 72 |

| ALPL | Cat | NM_001042563.1 | GGACGGCCTGAACCTCG | GAGTTCGGT GCGGTTCCA | 85 |

All reactions were performed as technical duplicates with the inclusion of combined RT-controls and negative controls also performed in duplicate on a Light Cycler 480 (Roche Diagnostics, Vienna, Austria).

2.6. DNA-Fingerprint Assay

DNA of original fresh frozen tumor aliquots and primary cell cultures (passages used were: COS_1033: P5, FOS_1077: P12, COS_1140: P15, COS_1186h: P4, COS_1186w: P7, COS_1189: P23, COS_1220: P6) were isolated using the Nucleo Spin Tissue Kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany). In brief, ~20 ng of tissue or a pellet of 105 to 106 cells was used as starting material. Tumor tissue samples were homogenized in T1 buffer (Macherey-Nagel) using zirconium beads (PEQLAB Biotechnologie, Erlangen, Germany) in the MagNA Lyser (Roche Diagnostics) for 2 times 20 s at 6500 rpm and were cooled on ice in between. Cultured tumour cells were homogenized by vortexing vigorously in T1 buffer (Macherey-Nagel). Homogenates were than lysed with proteinase K (Macherey-Nagel) for 15 min and DNA isolated as described in the manufacturers protocol.

DNA was sent to Laboklin (Bad Kissingen, Germany) for DNA fingerprinting determining 18/16 marker regions for dogs or cats, respectively [35].

3. Results

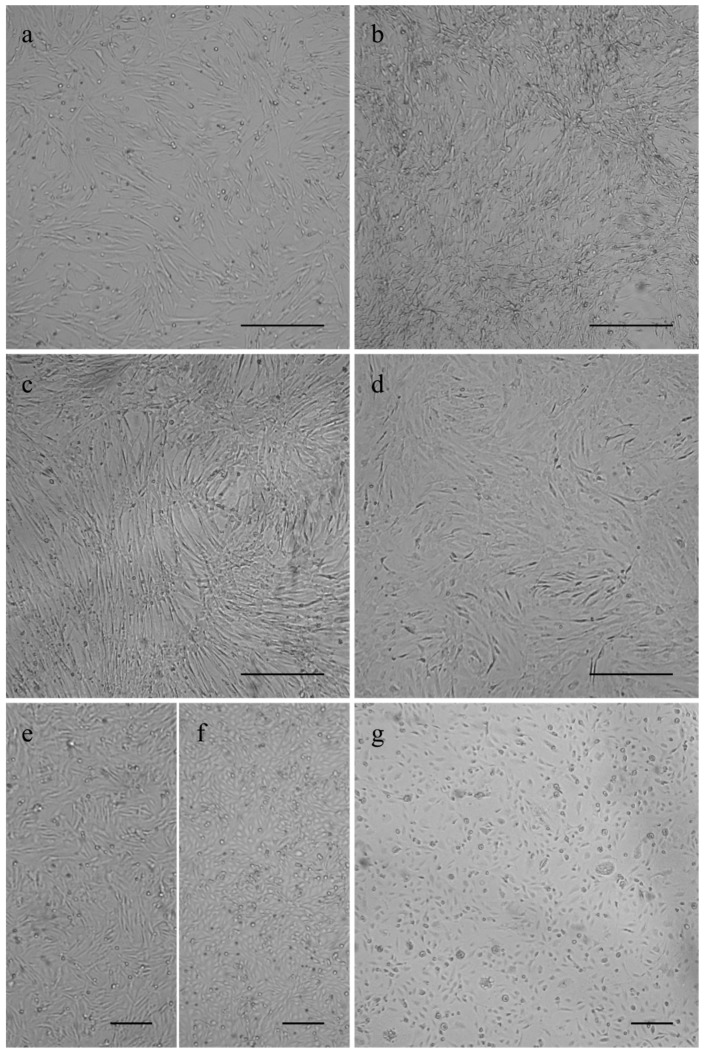

The canine osteosarcoma cells COS_1033, COS_1189 and COS_1220 were successfully grown to the passages 8, 25, and 6, respectively. The canine tumor 1186 macroscopically showed a distinct separation in a hard, bone- or cartilage-like area and a soft tissue-like area. Separate tissue cultures were established from both tumor parts and labelled as COS_1186h for the hard part and COS_1186w for the soft part, respectively. COS_1186h was grown to passage 4 and COS_1186w was grown to passage 7. The feline osteosarcoma cell lines were grown up to passage 21 for FOS_1077 and 19 for FOS_1140. Cells did not change their growth characteristics or proliferation within the stated number of passages. Most canine cell lines, namely COS_1033, COS_1186w, COS_1189, and COS_1220, showed a fibroblast-like morphology when grown as monolayers on plastic cell culture dishes or glass surfaces irrespective from the tumor subtype (Figure 1). In contrast, the “sister cell line” of COS_1186w (obtained from the same tumor), COS_1186h, showed a cobblestone epithelial-like morphology (Figure 1). Feline osteosarcoma cell lines (FOS_1077 and FOS_1140) had a mixed morphology of fibroblast-like cells and osteoblast like cells (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Phase contrast images showing growth morphology of (a) COS_1033 at P4; (b) COS_1189 at P7; (c) COS_1220 at P4; (d) FOS_1140 at P4; (e) COS_1186w at P3; (f) COS_1186h at P4; and (g) FOS_1077 at P4. Scale bars represent 100 µm for (a–d) and 200 µm for (e–g).

COS_1189 showed a weak attachment to plastic surfaces and once a continuous layer of cells was formed (~70%–80% confluency), even light agitation of the cell culture dish led to the detachment of sheets of cells which formed spheroids spontaneously.

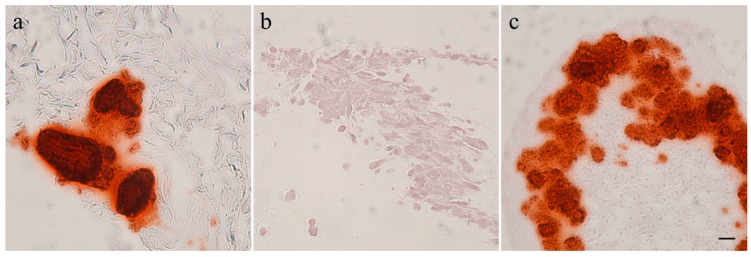

Calcification of the tumors and tumor cell cultures was determined by alizarin red staining. Feline tumor 1077 and canine tumor 1186 showed large areas of calcification; in the latter both in the macroscopically hard and soft areas. The three other canine osteosarcomas showed only few calcified spots and no signs of calcification were found in feline osteosarcoma 1140. It has to be noted that the amount of calcification was observed to be very heterogeneous within the tumors. All canine and feline cell cultures were alizarin red negative after two (COS_1033), three (COS_1186w and COS_1220), four (COS_1186h), five (FOS_1077), seven (FOS_1140), or 11 (COS_1189) days of culture. The spontaneously-developing spheroids, as observed in COS_1189 cultures, showed strong calcification after three days in culture, as demonstrated by alizarin red staining (Figure 2), but the center of the spheroids also showed signs of necrosis.

Figure 2.

Alizarin red staining of (a) a tumor section of 1189; (b) a monolayer cell culture sample of COS_1189; and (c) a spheroid of COS_1189. Scale bar represents 20 µm.

3.1. Immunohistochemistry

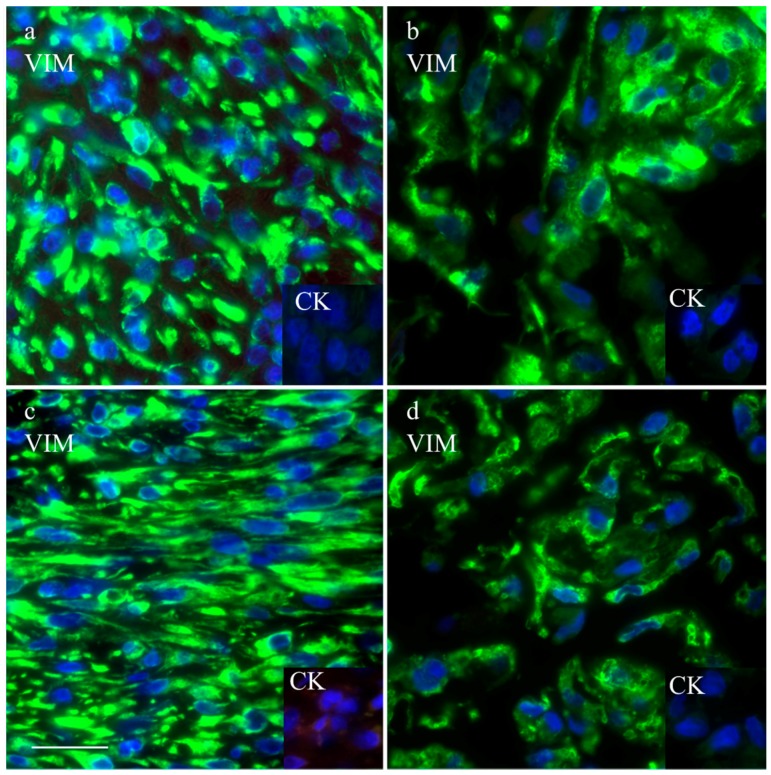

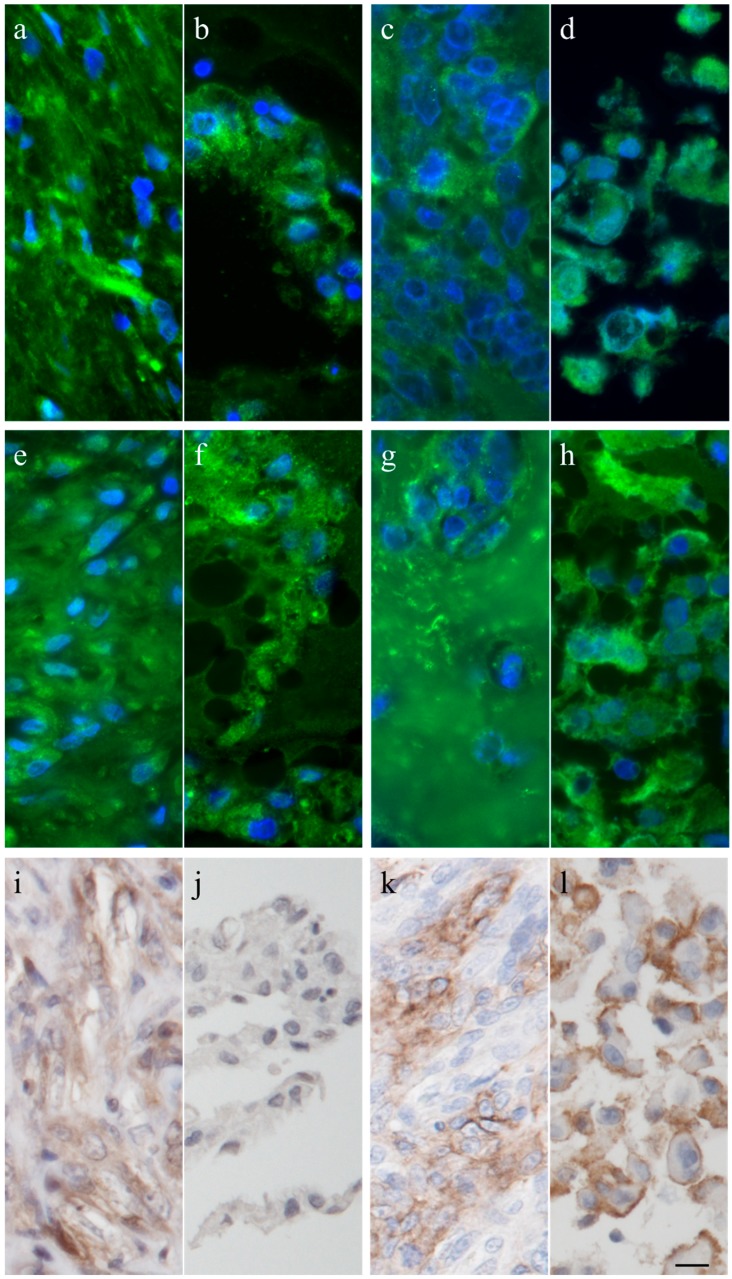

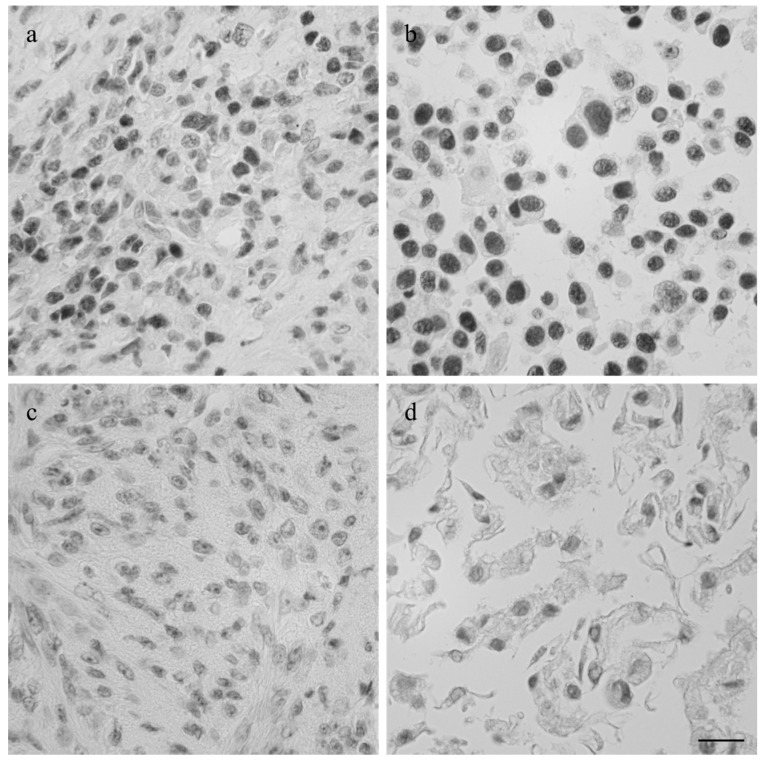

The intermediate filament cytoskeleton of the cultivated cells, irrespective of their morphology, was composed of vimentin as expected for mesenchymal cells and as also seen in the corresponding histological tumor sections (Figure 3). Cytokeratin positive tumor cells were never observed, neither in the original tumors nor in the cultivated tumor cells (Figure 3). Immunohistochemistry demonstrated osteonectin and osteocalcin in every examined tumor, albeit in different intensity levels (Figure 4). Osteonectin was less abundant in cat tumors compared to their canine counterparts. The expression of these proteins was also detectable in the respective corresponding cell cultures of feline and canine osteosarcomas (Figure 4). All feline and canine osteosarcomas were positive for tissue unspecific alkaline phosphatase. This marker remained unchanged in the corresponding primary cell cultures with the exception of one canine cell line (COS_1220) where the original tumor was positive, but no expression was observed in the cell culture. The distribution of the signal was cytoplasmic, membrane bound or nuclear (Figure 4). p53 showed no staining in cats, whether the tumor itself or the corresponding cell culture, but was present in nuclei of all canine cell lines (Figure 5). It has to be noted that the tumor 1189 showed only very few stained cells, while the resulting cell line COS_1189 was clearly positive.

Figure 3.

Immunofluorescence staining with anti-vimentin and anti-cytokeratin (inserts) of the canine tumor 1033 (a) and the resulting cell culture (b) as well as the feline tumor 1077 (c) and its resulting cell culture (d). Scale bar represents 25 µm.

Figure 4.

Immunhistochemistry and immunofluorescence of canine tumor 1220 (a,e,i) and its cell line (b,f,j), and the feline tumor 1077 (c,g,k) and its cell line (d,h,l) showing osteonectin (a–d), osteocalcin (e–h), and tissue unspecific alkaline phosphatase (i–l). Scale bar represents 10 µm.

Figure 5.

Imunhistological staining of p53 in the canine tumor 1189 (a) and feline osteosarcoma 1140 (c), and the cell lines COS_1189h (b) and FOS_1140 (d) derived from these tumors. Scale bar represents 20 µm.

3.2. PCR

By means of PCR, the presence of mRNA of tissue unspecific alkaline phosphatase (ALPL) and osteonectin (SPARC) was detected positively in all tested feline and canine tissue and cell culture samples, except for the cell culture samples of COS_1220 which lost ALPL expression, mirroring the results obtained by immunohistochemistry. However, we failed to amplify osteocalcin (BGLAP) mRNA in feline and canine samples (A list of the results is supplied in Supplementary Table S1).

3.3. DNA Fingerprint Assay

Microsatellite analysis of the established primary cell lines confirmed their origin from the corresponding tumor. In feline samples 16 markers were tested. All markers were identical between tumor tissue and cells in culture. In dogs, 18 markers were tested. COS_1033 and COS_1186h cells and tumor were completely identical in their marker setup, although one marker failed to amplify in the latter, both in tumor and in the cell line. COS_1220 showed one allele changed in a single marker, COS_1189 had alterations in two alleles. Three markers differed between COS_1186w and the tumor, although one marker failed to amplify in the tumor sample, but not in the cell line. A complete list of the obtained microsatellite data as first published in [35] is supplied in Supplementary Tables S2 and S3. These lists can be helpful in future experiments to exclude cross contaminations.

4. Discussion

Osteosarcomas are the most common bone neoplasms in humans [12], dogs [36], and cats [37]. Osteosarcomas in dogs are considered a valuable model for human osteosarcomas, because of the similar behavior of these two diseases concerning tumor progression and metastasis development in the lung [9,10,38]. In contrast, little research has been done on feline osteosarcomas, but current data points to a much less severe progress with less likelihood of metastasis in this species, although the histological properties of the primary tumor are very similar to its human and canine counterpart [27,26]. Osteosarcoma cell lines have been applied in many fields of research such as drug development [39,40], drug resistance development [41], and basic tumor research [42,43]. Mostly, these studies have been focused on human osteosarcoma cell lines [39,41,42,43,44], but also osteosarcomas of rat [45], mouse [46], and dog [40,43,46] were used for investigations. The use of canine and feline osteosarcoma cell cultures would be of particular interest allowing scientists to investigate the biological differences of these two species as reflected by the diverse metastatic behavior of these otherwise very similar tumors. Today, no feline osteosarcoma cell line is available or described in the literature to investigate their specificities and to use them in experimental applications.

We, therefore, developed five canine, and two feline, primary cell lines out of three canine osteosarcomas, one canine osteosarcoma-derived lung metastasis, and two feline osteosarcomas. Tumor cells attached to the plastic surface in a standard cell culture environment and were readily grown in provided media supplemented with fetal calf serum. Initially, two standard media (DMEM and Q286) and a medium specialized for the rearing of osteoblast cells (OGM), were chosen to initiate cell culture, however no preference to a single medium by a certain cell line was apparent. The applied method of establishment of the primary cell lines was robust and repeatable. There are two different main approaches for bringing osteosarcoma cells into culture, either by digesting the tumor matrix by collagenases [20,21] or by directly bringing minced pieces of osteosarcoma into cell culture [22,32]. While the digesting approach leads to a higher number of cells more quickly, and might be beneficial if cells need a high density for survival, it might damage the cells [47]. We have chosen the mincing approach because we are convinced that, preferably, tumor cells will grow out of the minced pieces, reducing contamination from non-tumor cells in the early passages.

Canine cell lines had a strong tendency to produce a fibroblast like morphology in cell cultures COS_1033, COS_1186w, COS_1189, and COS_1220, irrespective of the subtype. Only COS_1186h kept the osteoblastic morphology of the originally osteoblastic osteosarcoma in cell culture. Both feline cell lines showed a mixed phenotype of osteoblastic and fibroblastic cells. The differences in the morphology of the two sister cell lines COS_1186w and COS_1186h confirms the well-known inter-tumoral heterogeneity of the osteosarcoma [48,49]. Two tumor cell lines with basically the same genetic layout, but different morphological features, offers interesting prospects to further the understanding of tumor development, progression and drug response.

COS_1189 cells showed a strong tendency to adhere more strongly to each other than to the plastic surface of the dishes they were grown in. Depending on the confluency of cells and size of the dish, spheroids could be produced by simply shaking the dish. If done cautiously all cells tended to aggregate to one spheroid, but more likely two to four spheroids developed. Due to these large assembled spheroids, nutritional supply for cells in the middle was limited and these cells showed signs of degradation at the time of collection. In contrast to the cells grown as monolayers, cells within the spheroid deposited calcified osteoid-like areas, resembling the in vivo situation in osteosarcomas. We assume that a three-dimensional culture model would be preferable to better mimic the in vivo situation.

The established cell lines retained most of the characteristics of the tumors they derived from. We used the bone markers osteonectin [20,32,46], osteocalcin [31], and tissue unspecific alkaline phosphatase [29,30] at the protein and mRNA levels, confirming the origin of the cells that were obtained in cultures. These findings are in accordance with previously-established osteosarcoma cell lines that were positive for osteonectin, osteocalcin, and tissue unspecific alkaline phosphatase [30].

Alkaline phosphatase activities were found in other canine osteosarcoma cell lines [18,20,30] but also described as low [21]. Legare et al. [30] reported that most tested canine cell lines lost alkaline phosphatase immunoreactivity during culture time, however, only the very aggressive “Abrams” cell line consistently stained positive. In human osteosarcoma cells, tissue unspecific alkaline phosphatase activity was dependent on cell density [19], therefore, this condition has to be considered when comparing data about alkaline phosphatase. No data about alkaline phosphatase in feline osteosarcoma tumors or cell lines exist until now. Although higher serum levels of alkaline phosphatase have been correlated with shorter survival time [38], our results do not support tissue unspecific alkaline phosphatase as a distinguishing marker for the aggressive canine osteosarcoma from the low metastasizing feline osteosarcoma, as samples of both species were positive for tissue unspecific alkaline phosphatase, albeit the sampled tumor section of osteosarcoma 1189 showed only weak staining.

Osteocalcin, a small peptide hormone produced by osteoblasts, was used to verify the bony origin of our new cell lines. Immunhistochemistry was positive for osteocalcin in all tested samples, however, RT-PCR failed in all tested cases. Bioinformatically, osteocalcin is highly conserved and only one splice variant and one polycistronic mRNA containing BGLAP (PMF1-BGLAP) is known in the best-studied species, humans, and forms of these two transcripts are also predicted in cats and dogs. We are unsure why primers for this gene failed. Additionally, while all positive controls failed for this gene we do not consider it as evidence against the osteocalcin-antibody specificity.

Osteonectin is one of the most abundant proteins in the bone. It was present in all tested tumors and cell cultures, but its staining was notably weaker in feline tumors than it was canine osteosarcomas. Osteonectin is known to have tumor-progressing or -suppressing properties, depending on the surrounding cellular environment, and seems to be a negative prognostic marker in human osteosarcoma patients [50], indicating a valuable candidate gene that might influence the progression of osteosarcoma.

All established canine and feline cell cultures expressed vimentin irrespective of growth behavior but were negative for cytokeratin. This result is in contrast with the data from Nagamine et al. [51] who found canine osteosarcomas of various subtypes positive for cytokeratin and vimentin.

We tested calcification of tumor tissue and cell lines by alizarin red staining. All tumor samples showed calcified areas, except one feline tumor (1140), but no cell monolayer showed an alizarin positive staining. However, the spontaneous spheroids developed by COS_1189 showed alizarin red staining. While Mohseny et al. [33] showed that monolayers of HOS cells showed strong calcification, Martins-Neves et al. [34] showed only alizarin-positive spheroids, although both were grown in the media RPMI 1640. Prolonged sustaining the cells as a monolayer or differences in cell culture maintenances might influence calcification and explain these differences.

p53 is a transcription factor that is involved in cell cycle control [52] and it is known that disruption of p53 function strongly correlates with tumorigenesis [53]. In all our established canine cell lines p53 was present, as in their corresponding tumors. This is in accordance with the results of Bongiovanni et al. [54] who found p53 in canine appendicular osteosarcoma by means of immunohistochemistry. Moreover, p53 was correlated with the histological grade, as grade III tumors were 100% positive in canine osteosarcoma, and found to be a negative prognostic marker [54]. Interestingly, p53 was negative in both investigated feline tumors and the corresponding cell lines. It has been reported before that only about 50% of feline osteosarcomas express p53 [55] and that feline tumors tend to delete p53 [56]. Positivity might also be correlated to a certain subtype of osteosarcoma, however, tumor type was not stated in the report of Nasir et al. [55] and the number of cases investigated was low. Therefore, this hypothesis has to be verified on a statistically significant number of feline osteosarcomas. Further studies are needed to determine if p53 is involved in the characteristically lower tumor grades and enhanced survival of osteosarcoma affected cats.

The ability of tumor cell lines to produce tumors in immunodeficient laboratory animals is considered important for the characterization of neoplastic cell lines [18,20,21]. However, we consider the screened markers sufficient to confirm the origin of the newly produced cell lines as shown by other groups before [21,29,32]. However, comparative in vivo testing of the feline and canine osteosarcoma cell lines would, of course, add valuable data to their further experimental application. Therefore, their tumor formation capacity should be tested in future studies.

5. Conclusions

We have confirmed the osteosarcoma origin of the newly developed cell lines. They broaden the available species for in vitro osteosarcoma research to a species that is known to have a much better survival prognosis than humans or dogs. Species-specific differences, like the distinct expression of the oncogene p53, could be helpful to elucidate the biological reasons for the differences in feline and canine osteosarcoma progression. This research might also open interesting experimental tools to test potential therapeutic applications in vitro.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF), grant number P 23336-B11. We would like to express our gratitude to Anne Fleming, Claudia Höchsmann, Hans Homola and Brigitte Machac for their technical support.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at www.mdpi.com/2306-7381/3/2/9/s1, Table S1: Results of qualitative RT-PCR to determine the mRNA expression of ALPL, SPP1, SPARC and BGLAP; Table S2: Length of microsateites in dogs used to confirm the cell cultues origins; Table S3: Length of microsateites in cats used to confirm the cell cultues origins.

Author Contributions

Ingrid Walter conceived the study. Florian R.L. Meyer produced the cell lines. Florian R.L. Meyer and Ingrid Walter analyzed the samples, data, interpreted the results and wrote the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.World Cancer Research Fund International. [(accessed on 31 May 2016)]. Available online: https://www.wcrf.org/int/cancer-facts-figures/data-cancer-frequency-country.

- 2.Dorn C.R., Taylor D.O., Schneider R., Hibbard H.H., Klauber M.R. Survey of animal neoplasms in Alameda and Contra Costa Counties, California. II. Cancer morbidity in dogs and cats from Alameda County. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1968;40:307–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boerma M., Burton G.R., Wang J., Fink L.M., McGehee R.E., Hauer-Jensen M. Comparative expression profiling in primary and immortalized endothelial cells: Changes in gene expression in response to hydroxy methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase inhibition. Blood Coagul. Fibrinolysis. 2006;17:173–180. doi: 10.1097/01.mbc.0000220237.99843.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lidington E., Moyes D., McCormack A., Rose M. A comparison of primary endothelial cells and endothelial cell lines for studies of immune interactions. Transpl. Immunol. 1999;7:239–246. doi: 10.1016/S0966-3274(99)80008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rockwell S. In vivo-in vitro tumour cell lines: Characteristics and limitations as models for human cancer. Br. J. Cancer. Suppl. 1980;4:118–122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson H., Huelsmeyer M., Chun R., Young K.M., Friedrichs K., Argyle D.J. Isolation and characterisation of cancer stem cells from canine osteosarcoma. Vet. J. 2008;175:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2007.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levings P.P., McGarry S.V., Currie T.P., Nickerson D.M., McClellan S., Ghivizzani S.C., Steindler D.A., Gibbs C.P. Expression of an exogenous human Oct-4 promoter identifies tumor-initiating cells in osteosarcoma. Cancer Res. 2009;69:5648–5655. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Di Fiore R., Santulli A., Drago Ferrante R., Giuliano M., de Blasio A., Messina C., Pirozzi G., Tirino V., Tesoriere G., Vento R. Identification and expansion of human osteosarcoma-cancer-stem cells by long-term 3-aminobenzamide treatment. J. Cell. Physiol. 2009;219:301–313. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vail D.M., Macewen E.G. Spontaneously occurring tumors of companion animals as models for human cancer. Cancer Investig. 2000;18:781–792. doi: 10.3109/07357900009012210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Withrow S.J., Powers B.E., Straw R.C., Wilkins R.M. Comparative aspects of osteosarcoma. Dog versus man. Clin. Orthop. 1991:159–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruland O.S. Hematogenous micrometastases in osteosarcoma patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005;11:4666–4673. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mirabello L., Troisi R.J., Savage S.A. Osteosarcoma incidence and survival rates from 1973 to 2004: Data from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program. Cancer. 2009;115:1531–1543. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Misdorp W., Hart A.A. Some prognostic and epidemiologic factors in canine osteosarcoma. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1979;62:537–545. doi: 10.1093/jnci/62.3.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gelberg K.H., Fitzgerald E.F., Hwang S., Dubrow R. Growth and development and other risk factors for osteosarcoma in children and young adults. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1997;26:272–278. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.2.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Longhi A., Pasini A., Cicognani A., Baronio F., Pellacani A., Baldini N., Bacci G. Height as a risk factor for osteosarcoma. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2005;27:314–318. doi: 10.1097/01.mph.0000169251.57611.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelsey J.L., Moore A.S., Glickman L.T. Epidemiologic studies of risk factors for cancer in pet dogs. Epidemiol. Rev. 1998;20:204–217. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a017981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fodstad O., Brøgger A., Bruland O., Solheim O.P., Nesland J.M., Pihl A. Characteristics of a cell line established from a patient with multiple osteosarcoma, appearing 13 years after treatment for bilateral retinoblastoma. Int. J. Cancer. 1986;38:33–40. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910380107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kadosawa T., Nozaki K., Sasaki N., Takeuchi A. Establishment and characterization of a new cell line from a canine osteosarcoma. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 1994;56:1167–1169. doi: 10.1292/jvms.56.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pautke C., Schieker M., Tischer T., Kolk A., Neth P., Mutschler W., Milz S. Characterization of osteosarcoma cell lines MG-63, Saos-2 and U-2 OS in comparison to human osteoblasts. Anticancer Res. 2004;24:3743–3748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Séguin B., Zwerdling T., McCallan J.L., DeCock H.E.V., Dewe L.L., Naydan D.K., Young A.E., Bannasch D.L., Foreman O., Kent M.S. Development of a new canine osteosarcoma cell line. Vet. Comp. Oncol. 2006;4:232–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5829.2006.00112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hong S.H., Kadosawa T., Mochizuki M., Matsunaga S., Nishimura R., Sasaki N. Establishment and characterization of two cell lines derived from canine spontaneous osteosarcoma. J. Vet. Med. 1998;60:757–760. doi: 10.1292/jvms.60.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McAllister R.M., Gardner M.B., Greene A.E., Bradt C., Nichols W.W., Landing B.H. Cultivation in vitro of cells derived from a human osteosarcoma. Cancer. 1971;27:397–402. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197102)27:2<397::AID-CNCR2820270224>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ponten J., Saksela E. Two established in vitro cell lines from human mesenchymal tumours. Int. J. Cancer. 1967;2:434–447. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910020505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fogh J., Trempe G. New human tumor cell lines. In: Fogh J., editor. Human Tumor Cells in Vitro. Springer U.S.; New York, NY, USA: 1975. pp. 115–159. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Billiau A., Edy V.G., Heremans H., Van Damme J., Desmyter J., Georgiades J.A., de Somer P. Human interferon: Mass production in a newly established cell line, MG-63. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1977;12:11–15. doi: 10.1128/AAC.12.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riggs J.L., McAllister R.M., Lennette E.H. Immunofluorescent studies of RD-114 virus replication in cell culture. J. Gen. Virol. 1974;25:21–29. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-25-1-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dimopoulou M., Kirpensteijn J., Moens H., Kik M. Histologic prognosticators in feline osteosarcoma: A comparison with phenotypically similar canine osteosarcoma. Vet. Surg. 2008;37:466–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950X.2008.00409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heldmann E., Anderson M.A., Wagner-Mann C. Feline osteosarcoma: 145 Cases (1990–1995) J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 2000;36:518–521. doi: 10.5326/15473317-36-6-518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holmes K.E., Thompson V., Piskun C.M., Kohnken R.A., Huelsmeyer M.K., Fan T.M., Stein T.J. Canine osteosarcoma cell lines from patients with differing serum alkaline phosphatase concentrations display no behavioural differences in vitro: OSA cell lines differing in serum ALP. Vet. Comp. Oncol. 2015;13:166–175. doi: 10.1111/vco.12031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Legare M.E., Bush J., Ashley A.K., Kato T., Hanneman W.H. Cellular and phenotypic characterization of canine osteosarcoma cell lines. J. Cancer. 2011;2:262. doi: 10.7150/jca.2.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fanburgsmith J., Bratthauer G., Miettinen M. Osteocalcin and osteonectin immunoreactivity in extraskeletal osteosarcoma: A study of 28 cases. Hum. Pathol. 1999;30:32–38. doi: 10.1016/S0046-8177(99)90297-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Loukopoulos P., O’Brien T., Ghoddusi M., Mungall B., Robinson W. Characterisation of three novel canine osteosarcoma cell lines producing high levels of matrix metalloproteinases. Res. Vet. Sci. 2004;77:131–141. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mohseny A.B., Machado I., Cai Y., Schaefer K.-L., Serra M., Hogendoorn P.C.W., Llombart-Bosch A., Cleton-Jansen A.-M. Functional characterization of osteosarcoma cell lines provides representative models to study the human disease. Lab. Investig. 2011;91:1195–1205. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2011.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martins-Neves S.R., Lopes Á.O., do Carmo A., Paiva A.A., Simões P.C., Abrunhosa A.J., Gomes C.M. Therapeutic implications of an enriched cancer stem-like cell population in a human osteosarcoma cell line. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:139. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meyer F.R.L., Steinborn R., Grausgruber H., Wolfesberger B., Walter I. Expression of platelet-derived growth factor BB, erythropoietin and erythropoietin receptor in canine and feline osteosarcoma. Vet. J. 2015;206:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morello E., Martano M., Buracco P. Biology, diagnosis and treatment of canine appendicular osteosarcoma: Similarities and differences with human osteosarcoma. Vet. J. 2011;189:268–277. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2010.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pool R.R., Thompson K.G. Tumors of joints. In: Meuten D.J., editor. Tumors in Domestic Animals. Iowa State Press; Ames, IA, USA: 2002. pp. 199–243. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mueller F., Fuchs B., Kaser-Hotz B. Comparative biology of human and canine osteosarcoma. Anticancer Res. 2007;27:155–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chang Y.S., Graves B., Guerlavais V., Tovar C., Packman K., To K.-H., Olson K.A., Kesavan K., Gangurde P., Mukherjee A., Baker T., et al. Stapled α-helical peptide drug development: A potent dual inhibitor of MDM2 and MDMX for p53-dependent cancer therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:3445–3454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303002110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Couto J.I., Bear M.D., Lin J., Pennel M., Kulp S.K., Kisseberth W.C., London C.A. Biologic activity of the novel small molecule STAT3 inhibitor LLL12 against canine osteosarcoma cell lines. BMC Vet. Res. 2012;8:244. doi: 10.1186/1746-6148-8-244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lourda M., Trougakos I.P., Gonos E.S. Development of resistance to chemotherapeutic drugs in human osteosarcoma cell lines largely depends on up-regulation of Clusterin/Apolipoprotein J. Int. J. Cancer. 2007;120:611–622. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Montanini L., Lasagna L., Barili V., Jonstrup S.P., Murgia A., Pazzaglia L., Conti A., Novello C., Kjems J., Perris R., et al. MicroRNA cloning and sequencing in osteosarcoma cell lines: Differential role of miR-93. Cell. Oncol. Dordr. 2012;35:29–41. doi: 10.1007/s13402-011-0059-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sharili A.-S., Allen S., Smith K., Price J., McGonnell I.M. Snail2 promotes osteosarcoma cell motility through remodelling of the actin cytoskeleton and regulates tumor development. Cancer Lett. 2013;333:170–179. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rimann M., Laternser S., Gvozdenovic A., Muff R., Fuchs B., Kelm J.M., Graf-Hausner U. An in vitro osteosarcoma 3D microtissue model for drug development. J. Biotechnol. 2014;189:129–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Majeska R.J., Rodan S.B., Rodan G.A. Parathyroid hormone-responsive clonal cell lines from rat osteosarcoma. Endocrinology. 1980;107:1494–1503. doi: 10.1210/endo-107-5-1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mohseny A.B., Hogendoorn P.C.W., Cleton-Jansen A.-M. Osteosarcoma Models: From cell lines to Zebrafish. Sarcoma. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/417271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mather J.P., Roberts P.E. Introduction to Cell and Tissue Culture: Theory and Technique. Springer Science & Business Media; Berlin, Germany: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hiddemann W., Roessner A., Wörmann B., Mellin W., Klockenkemper B., Bösing T., Büchner T., Grundmann E. Tumor heterogeneity in osteosarcoma as identified by flow cytometry. Cancer. 1987;59:324–328. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19870115)59:2<324::AID-CNCR2820590226>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kunz P., Fellenberg J., Moskovszky L., Sápi Z., Krenacs T., Poeschl J., Lehner B., Szendrõi M., Ewerbeck V., Kinscherf R., et al. Osteosarcoma microenvironment: Whole-slide imaging and optimized antigen detection overcome major limitations in immunohistochemical quantification. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e90727. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dalla-Torre C.A., Yoshimoto M., Lee C.-H., Joshua A.M., de Toledo S.R., Petrilli A.S., Andrade J.A., Chilton-MacNeill S., Zielenska M., Squire J.A. Effects of THBS3, SPARC and SPP1 expression on biological behavior and survival in patients with osteosarcoma. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:237. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nagamine E., Hirayama K., Matsuda K., Okamoto M., Ohmachi T., Kadosawa T., Taniyama H. Diversity of histologic patterns and expression of cytoskeletal proteins in canine skeletal osteosarcoma. Vet. Pathol. 2015 doi: 10.1177/0300985815574006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kastan M.B., Canman C.E., Leonard C.J. P53, cell cycle control and apoptosis: Implications for cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1995;14:3–15. doi: 10.1007/BF00690207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Donehower L.A., Harvey M., Slagle B.L., McArthur M.J., Montgomery C.A., Butel J.S., Bradley A. Mice deficient for p53 are developmentally normal but susceptible to spontaneous tumours. Nature. 1992;356:215–221. doi: 10.1038/356215a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bongiovanni L., Mazzocchetti F., Malatesta D., Romanucci M., Ciccarelli A., Buracco P., de Maria R., Palmieri C., Martano M., Morello E., et al. Immunohistochemical investigation of cell cycle and apoptosis regulators (survivin, β-catenin, p53, caspase 3) in canine appendicular osteosarcoma. BMC Vet. Res. 2012;8:78. doi: 10.1186/1746-6148-8-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nasir L., Rutteman G.R., Reid S.W., Schulze C., Argyle D.J. Analysis of p53 mutational events and MDM2 amplification in canine soft-tissue sarcomas. Cancer Lett. 2001;174:83–89. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3835(01)00637-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mayr B., Reifinger M., Loupal G. Polymorphisms in feline tumour suppressor gene p53. Mutations in an osteosarcoma and a mammary carcinoma. Vet. J. 1998;155:103–106. doi: 10.1016/S1090-0233(98)80044-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.