Abstract

Objective

To estimate the prevalence of obesity and overweight and associated factors in indigenous people of the Jaguapiru village in Central Brazil.

Methods

We conducted a population-based cross-sectional study between January 2009 and July 2011 in the adult native population of the Jaguapiru village, Central Brazil. Sociodemographic and lifestyle data were obtained; anthropometric measures, arterial blood pressure, and blood glucose were measured. The independent variables were tested by Poisson regression, and the interactions between them were analyzed.

Results

1,608 indigenous people (982 females, mean age 37.7 ± 15.1 years) were included. The prevalence of obesity was 23.2% (95% CI 20.9-25.1%). Obesity was more prevalent among 40- to 49-year-old and overweight among 50- to 59-year-old persons. Obesity was positively associated with female sex, higher income, and hypertension. Among indigenous people, interactions were found with hypertension and sedentary lifestyle - hypertension in males and sedentary lifestyle in females.

Conclusions

The prevalence of obesity and overweight in indigenous people of the Jaguapiru village is high. Males as well as hypertensive and higher family income individuals have higher rates. Sedentary lifestyle and hypertension leverage the rates of obesity. Prevention and adequate public health policies can be critical for the control of excess weight and its comorbidities among Brazilian indigenous people.

Key Words: Obesity, Overweight, Prevalence, South American Indians, Brazil

Introduction

Obesity and overweight among some previously investigated indigenous populations have been reported to be high [1,2,3,4]. Although genetic factors can predispose to the development of obesity, its high prevalence among indigenous populations is attributed to environmental and behavioral factors, such as lack of physical activity and diet rich in carbohydrates and poor in fibers [5]. In Brazil, however, the data related to excess weight in indigenous communities are segmented, scarce, and feature varied prevalence values in different communities [6,7,8]. Moreover investigation is aggravated by the fact that some indigenous communities remain isolated, whereas others have integrated into the surrounding population [9]. Nearly 1 million indigenous people are distributed in 688 communities that occupy 12% of the Brazilian territory.

Obesity is an independent risk factor for the development of non-infectious chronic diseases such as systemic arterial hypertension, heart disease, dyslipidemia, immunological disorders, certain types of cancer, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes mellitus [10,11,12,13,14]. The concentration of fat in the abdominal region is believed to increase the risk of cardiovascular events [15], and many consider waist circumference the best indicator of visceral obesity [16,17]. The stratification of cardiovascular risk can also be evaluated using BMI [18]. A previous study performed in 2009 in Jaguapiru village including 606 indigenous people aged 18-69 years found that 36% of the individuals had metabolic syndrome, 40% were overweight and 23% were obese, which indicate that this population could be at high risk for cardiometabolic diseases [19].

The goal of present study was to assess the prevalence of obesity and overweight among the whole population of adult indigenous people from the Jaguapiru village. We aimed to also investigate existing associations among the outcomes and socioeconomic and cardiometabolic variables. Our findings could contribute to the introduction of public health policies oriented towards the peculiarities of the Brazilian indigenous communities.

Material and Methods

This is a population-based cross-sectional study on the prevalence of obesity and overweight in the Jaguapiru village, and was conducted between January 2009 and July 2011. The village is located 5 km from the city of Dourados, in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil, and its residents belong to three ethnic groups: Kaiowá, Guarani, and Terena. The territory is densely populated: 6,830 indigenous people occupy an area of 1,500 hectares [9]. The original ecosystem has been degraded, with disappearance of native forests and wild life, which compromises their traditional subsistence activities. Their sociocultural organization is deteriorating, with the abandonment of traditional beliefs and customs [5].

Participants

The eligible population of the Jaguapiru village consisted of 982 females and 979 males aged 18 years or more during the study period [9]. Due to the small number of inhabitants in the village, we planned to include all eligible subjects in this age group. Self-reported mixed-race individuals and pregnant women were not included.

Data Sources

At the initial visit to the houses of the natives we explained the objectives of the study and collected information on demographic factors, socioeconomic status, physical activity, dietary habits, alcohol and tobacco consumption, health condition as well as personal and family history of hypertension and diabetes. The National Indian Foundation (Fundação Nacional do Índio; FUNAI) registry was used to assign ages to the indigenous individuals. A second visit was set, and the participants were instructed to prepare for fast overnight and blood glucose measurements.

During data collection, researchers received assistance from medical students of the University Diabetes League, from the Federal University of Grande Dourados. Researchers underwent extensive training for standardization of blood pressure measurements, anthropometric measures, blood glucose test, and filling out all the forms. Anthropometric, blood pressure, and blood glucose measurements were performed by the researchers (GFO, ATI, TRRO).

Anthropometric Measurements

Body weight (in kg) was measured with the individual wearing their habitual clothing, barefoot on a digital scale for adults. The scale had a 180 kg weight limit, a tubular structure, and a non-slip rubber base, and was calibrated monthly. Height was measured in centimeters with the individual standing, barefoot, on a portable aluminum stadiometer, capable of measuring a minimum of 0.80 m and a maximum of 2.20 m. The BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. Individuals were considered obese with a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 and overweight when BMI was between 25 and 29.9 kg/m2, in accordance to the World Health Organization criteria [18].

Waist circumference was recorded in centimeters and measured with the subject standing, using a non-stretching measuring tape positioned in the middle point between the lower edge of the last rib and the upper portion of the iliac crest. Waist circumference values of up to 90 cm in males and 80 cm in females were considered normal [20].

Arterial Blood Pressure and Blood Glucose Measurements

Trained medicine students measured the blood pressure using a quarterly calibrated aneroid sphygmomanometer with an adult cuff that was placed on the right arm of the participant while seating and after resting for 10 min. The final value of blood pressure was based on the arithmetic average of two consecutive measurements performed at an interval of 5 min. When the systolic and diastolic blood pressure showed differences greater than 4 mm Hg, a third measurement was taken, and the most discrepant measurement was disregarded. The diagnosis of hypertension was based on criteria from the guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension and of the European Society of Cardiology [21].

Blood glucose was measured after 12 h of fasting using a glucometer with a fast-reading test strip (glucose oxidase) that was calibrated weekly. Blood glucose from 70 to 99 mg/dl was considered normal and values from 100 to 125 mg/dl as abnormal. Individuals with fasting blood glucose between 100 and 125 mg/dl were given the oral glucose tolerance test. Participants with fasting blood glucose between 126 and 199 mg/dl were retested on another occasion. Diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance were diagnosed based on the criteria of the American Diabetes Association [22].

Statistical Analysis

The qualitative variables are expressed as absolute (n) and relative (%) frequencies; quantitative variables are expressed as mean and standard deviation. The prevalence of obesity was considered dependent variables of the study.

Univariate Poisson regression analyses with robust variance were conducted for sociodemographic and clinical independent variables (age, sex, hypertension, diabetes, physical activity, smoking, alcohol consumption, family history of diabetes and hypertension, educational level, and family income). Those with a p value < 0.25 were selected for inclusion as covariates in the multivariate analysis, and those with p < 0.05 remained in the multivariate analysis [23]. The modified Akaike's information criterion (quasi-likelihood based information criterion; QICu) was used to select multivariate models, and the model with the lowest QICu was selected [24]. A multiple Poisson regression with robust variance was fitted to the data. The existence of multicollinearity among the independent variables was assessed using the variance inflation factor. Prevalence ratios for each point and interval were obtained for the selected model. A level of significance less than 5% (p < 0.05) was used when determining the association between the variables.

All variables that were significantly associated to obesity in the multivariate model were tested for interactions between them.

Ethical Aspects

This research was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University Centre of Grande Dourados (Centro Universitário da Grande Dourados), under number 197/07 and by the Brazilian Research Ethics Committee (Comissão Nacional de Ética em Pesquisa) under number 14,453. All subjects agreed to participate in the study freely and signed an informed consent form.

Results

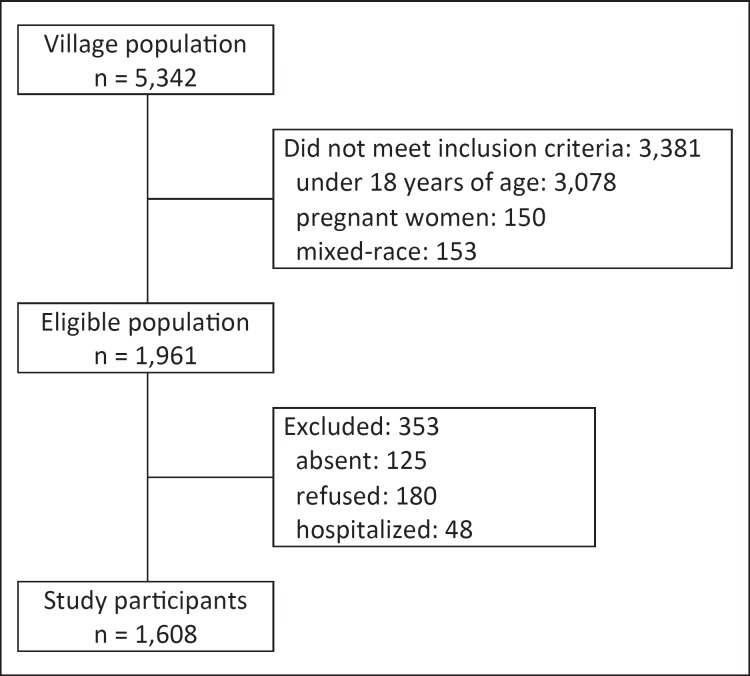

The village population was very young: 54% were under the age of 18 years and were not eligible for our study. A total of 1,608 indigenous individuals were included (fig. 1). The main characteristics of the study participants stratified by sex were previously described [25]. Diabetes was present in 5.8% of the population, and it was more frequent in individuals with obesity (10.5%; 95% CI 7.35-13.56%) than in those with overweight (5.9%; 95% CI 4.0-7.7%) and in normal-weight subjects (3.1%; 95% CI 1.7-4.4%).

Fig. 1.

The process of inclusion of participants in the study.

Alcohol consumption and tobacco usage were more frequent among males than among females. The overall prevalence of excess weight was 61% (66% for females and 56% for males). Most of the families had a monthly income of >1 to 2 minimum wages at the time of research. Household chores (81%) were the predominant activity among females, while working in the sugarcane plantations (35%) was the main activity for males (data not shown). Obese individuals were older than those with overweight and normal weight (table 1). The highest prevalence of overweight occurred in the age group of 50-59 years and among women. The mean waist circumference was 89.9 ± 11.3 cm. The prevalence of women with waist circumference above 80 cm was 76.7% (95% CI 73.9-79.5%) which was higher than the frequency of men with waist circumference above 90 cm (40.3%; 95% CI 36.8-43.9%).

Table 1.

Participants’ characteristics by subgroups of weight

| Variables | Normal weight | Overweight a | Obesity b | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 622) | (n = 613) | (n = 373) | (n = 1,608) | |

| Mean age (± SD), years | 34.1 ± 15.2 | 39.5 ± 14.8 | 41.0 ± 14.2 | 37.7 ± 15.1 |

| 18–29, n (%) | 328 (52.7) | 184 (30.0) | 90 (24.1) | 602 (37.4) |

| 30–49, n (%) | 187 (30.1) | 274 (44.7) | 182 (48.8) | 643 (40.0) |

| ≥50, n (%) | 107 (17.2) | 155 (25.3) | 101 (27.1) | 363 (22.6) |

| Females, n (%) | 304 (48.9) | 311 (50.7) | 264 (70.8) | 879 (54.7) |

| Educational level, n (%) | ||||

| No schooling | 427 (68.7) | 461 (75.2) | 281 (75.3) | 1,169 (72.7) |

| Elementary education | 112 (19.6) | 90 (14.7) | 54 (14.5) | 266 (16.5) |

| Secondary education | 60 (9.6) | 50 (8.2) | 29 (7.8) | 139 (8.6) |

| Higher education | 13 (2.1) | 12 (1.9) | 9 (2.4) | 34 (2.2) |

| Family income in minimum wages c , n (%) | ||||

| <1 | 251 (40.5) | 253 (41.3) | 155 (41.7) | 659 (41.1) |

| 1 to <2 | 221 (35.7) | 195 (31.9) | 125 (33.6) | 541 (33.7) |

| 2 to <3 | 115 (18.5) | 119 (19.4) | 57 (15.3) | 291 (18.1) |

| ≥3 | 33 (5.3) | 45 (7.4) | 35 (9.4) | 113 (7.1) |

| Smokers, n (%) | 143 (23.0) | 109 (17.8) | 54 (14.5) | 306 (19.0) |

| Alcohol consumption, n (%) | 143 (23.0) | 110 (17.9) | 52 (13.9) | 305 (8.1) |

| Physical activity, n (%) | 244 (39.2) | 230 (37.5) | 97 (26.0) | 571 (35.5) |

| Mean waist circumference cm | 80.6 ± 6.6 | 91.4 ± 6.4 | 103.2 ± 9.4 | 89.9 ± 11.3 |

| Mean weight (± SD), kg | 58.6 ± 7.8 | 69.6 ± 8.3 | 82.6 ± 12.2 | 68.3 ± 13.0 |

| Mean height (± SD), cm | 160.0 ± 8.8 | 159.6 ± 8.7 | 156.7 ± 7.9 | 159.1 ± 8.7 |

| Mean BMI (± SD), kg/m2) | 22.7 ± 1.6 | 27.2 ± 1.4 | 33.7 ± 3.5 | 27.0 ± 4.7 |

BMI 25–29.9 kg/m2.

BMI ≥30 kg/m2.

Minimum wage at study time: USD 315.00.

In individuals who were overweight, the diabetes mellitus rate was 9% in females and 5% in males (p < 0.01). Overweight was observed in 41% of male and 35% of female natives and was not significantly associated with hypertension or diabetes mellitus.

The prevalence of obesity was 23.2% (95% CI 20.9-25.1%) and was more common in females (30%) than in males (15%; p < 0.01). Arterial hypertension was prevalent among obese males (51%) and among females (43%), amounting to an average of 45% (data not shown).

The results of the association of obesity with the independent characteristics are given in table 2. The following variables were not significant to remain in the adjusted model, and were removed from the analysis: diabetes, smoking, alcohol consumption, family history of diabetes and hypertension, and educational level. The highest frequency of obesity was found in the age group 40-49 years; however, its prevalence was not significantly different from that detected in indigenous people aged above 60 years and in the reference group (indigenous individuals aged 18 and 29 years; prevalence ratio (PR) = 1.36; 95% CI 0.98-1.88; p = 0.07). In the age group of 30-39 years, obesity was positively associated with the higher stratum of family income.

Table 2.

Crude and adjusted prevalence ratio (PR) of obesity by characteristics of the study participants, based on Poisson multiple regression analysis

| Variables | Crude PR | 95% CI | p value | Adjusted PR | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||||||

| 18–29 | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| 30–39 | 1.88 | 1.47–2.40 | <0.001 | 1.70 | 1.33–2.18 | <0.001 |

| 40–49 | 1.95 | 1.47–2.59 | <0.001 | 1.48 | 1.11–1.97 | 0.01 |

| 50–59 | 1.91 | 1.41–2.60 | <0.001 | 1.43 | 1.03–1.97 | 0.03 |

| ≥60 | 1.85 | 1.37–2.49 | <0.001 | 1.36 | 0.98–1.88 | 0.07 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 1.00 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Female | 2.00 | 1.64–2.45 | <0.001 | 1.90 | 1.55–2.32 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | ||||||

| No | 1 | – | – | 1 | – | |

| Yes | 1.94 | 1.63–2.31 | <0.001 | 1.75 | 1.44–2.12 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | NS | NS | NS | |||

| No | 1 | – | ||||

| Yes | 1.88 | 1.45–2.43 | <0.001 | |||

| Physical activity | ||||||

| No | 1.58 | 1.28–1.95 | <0.001 | 1.25 | 1.01–1.54 | 0.04 |

| Yes | 1 | – | 1 | – | ||

| Smoking | NS | NS | NS | |||

| No | 1.39 | 1.07–1.80 | 0.014 | |||

| Yes | 1 | – | – | |||

| Alcohol consumption | NS | NS | NS | |||

| No | 1.44 | 1.11–1.88 | 0.065 | |||

| Yes | 1 | – | – | |||

| Family history of diabetes | NS | NS | NS | |||

| No | 1 | – | – | |||

| Yes | 1.51 | 1.26–1.82 | <0.001 | |||

| Family history of hypertension | NS | NS | NS | |||

| No | 1 | – | ||||

| Yes | 1.33 | 1.12–1.60 | 0.001 | |||

| Educational level | NS | NS | NS | |||

| No schooling | 1 | – | – | |||

| Elementary education | 0.84 | 0.65–1.09 | 0.19 | |||

| Secondary education | 0.87 | 0.62–1.23 | 0.44 | |||

| Higher education | 1.10 | 0.62–1.95 | 0.74 | |||

| Income (minimum wage)* | ||||||

| <1 | 1 | – | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| 1 to <2 | 0.98 | 0.80–1.21 | 0.87 | 1.14 | 0.93–1.40 | 0.19 |

| 2 to <3 | 0.83 | 0.63–1.09 | 0.18 | 0.93 | 0.72–1.20 | 0.58 |

| ≥3 | 1.32 | 0.97–1.79 | 0.08 | 1.46 | 1.08–1.96 | 0.01 |

NS = the variable was non-significant to be included in the adjusted model.

Minimum wage at study time: USD 315.00.

The following variables were significant in the multivariate model and were tested for interaction: age, sex, hypertension, physical activity, and family income. The interactions between sex and hypertension, sex and physical activity and hypertension and physical activity were significant (p < 0.001).

Hypertension in males (PR = 2.34; 95% CI 1.65-3.33) and sedentary lifestyle in females (PR = 2.36; 95% CI 1.77-3.16) were positively associated with obesity. We also observed that the combination of hypertension and sedentary lifestyle increased the prevalence of obesity 2.39-fold compared to individuals who were normotensive and physically active (95% CI 1.76-3.24). Comparing different gender tests for interaction, obesity was found 2.36 times more frequently in sedentary women than in physically active men (95% CI 1.77-3.16).

Discussion

Two-thirds of the women of the village and more than half of the males were overweight or obese, which is a higher percentage than that found in the Brazilian non-indigenous adult population, in which 50% of males and 48% of females are overweight [26]. These rates were also higher than those observed in several Brazilian indigenous populations, which ranged from 20 to 42% [6,8]. Among our male indigenous individuals, the prevalence of overweight was higher than that of the Brazilian non-indigenous population, of the Guarani people on the coast of Rio de Janeiro, and of the Aruák in Upper Xingu [6,7]. However, the rates of hypertension in the present study were similar to those of the non-indigenous population of Brazil [25].

The prevalence of obesity among females (30%) in the present study was higher than that found among Brazilian non-indigenous females (17%) [26] and within indigenous communities and rural communities in Minas Gerais, Brazil [6,27,28]. However, it should be noted that the previous Brazilian population study was conducted in urban and rural areas, which have different obesity rates. Still, in the females of the present study, obesity was more prevalent in those 50-59 years of age, which is similar to data reported by other authors [8,29]. In males, the obesity rate of was similar to that of the general population [26] and higher than the frequencies of 1.4-11.6% found in several indigenous and rural communities in Brazil [8,10,30]. However, the prevalence of obesity in the males found of our study was lower than that found in Chilean [28] and North-American Indians [31], Australian Aborigines [32]. This marked variation in the prevalence of obesity and overweight in the different populations studied may be due to genetic and environmental factors characteristic of each community. For example, indigenous people of the same ethnicity (Pima Indians), living in a remote mountainous area in northeastern Mexico, showed a lower prevalence of obesity (24.9%) compared to those who had migrated to Arizona, USA (33.4%) [32]. However, with respect to the fact that the males of the Jaguapiru village predominantly are laborers with well-developed muscle mass, the prevalence of overweight in this group should be evaluated with caution [33].

On the other hand, the prevalence of obesity observed among the Jaguapiru natives was below that described for indigenous individuals in Rio Grande do Sul (47%) [34]. A possible explanation for this difference is the scope of the population in terms of age: in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, the participants were over 39 years of age while in the present study individuals were above 18 years.

Unlike other studies, there was no evidence of association between education and obesity [35,36]. There was a positive association between obesity and higher family income, contrary to a previous report [6]. Only 18.1% of the families earned more than USD 630.00 per year. Most likely, these findings are due to low levels of education and family income of the natives, both of which might have been lower than in other studies. Our findings are consistent with several epidemiological studies that associate obesity and overweight with hypertension and diabetes mellitus [6,37]. The prevalence of obesity is 1.7- and 2-fold higher in cases with arterial hypertension and diabetes mellitus, respectively.

This study has some limitations. First, indigenous people from three ethnic groups were included: Guarani, Kaiowá and Terena, which have different epidemiological and genetic profiles. The prevalence of obesity varies widely in different populations [8,27], but a stratified analysis by ethnicity was not possible in present study. There was a slight predominance of females among the participants, possibly as a result of the temporary work performed by the males in sugar mills in the vicinity of the village. Lastly, excess weight was stratified according to BMI which may be incorrect as most males were laborers with well-developed muscle mass in whom higher BMI values may not represent an increase in fat tissue but rather in lean mass.

In conclusion, the prevalences of obesity and overweight in the population above 18 years of age in the Jaguapiru village are higher than those of the Brazilian population and comparable to some Brazilian indigenous communities. Females are at a greater risk for obesity than males. The data described herein suggest the need for changes in dietary habits and physical activity incentives among natives in the Jaguapiru village as a way to prevent overweight and obesity and its consequences. Such lifestyle modifications should be promoted by public health policies that take into consideration the socioeconomic and cultural conditions of the indigenous population.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Authorship Statement

GFO, TRRO, and ATI gave substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work and acquisition of data for the work. TFG, MTS, and MGP contributed in the analysis and interpretation of data for the work. All authors drafted the work and revised it critically for important intellectual content, gave the final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Federal University of Grande Dourados for sponsoring the costs of transportation and rapid test strips (glucose oxidase).

References

- 1.Misra KB, Endemann SW, Ayer M. Measures of obesity and metabolic syndrome in Indian Americans in northern California. Ethn Dis. 2006;16:331–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pavkov ME, Knowler WC, Bennett PH, Looker HC, Krakoff J, Nelson RG. Increasing incidence of proteinuria and declining incidence of end-stage renal disease in diabetic Pima Indians. Kidney Int. 2006;70:1840–1846. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare The health and welfare of Australia's Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples 2005. www.aihw.gov.au/publications/ (last accessed September 24, 2015).

- 4.Coimbra CE, Jr, Santos RV, Welch JR, Cardoso AM, de Souza MC, Garnelo L, Rassi E, Foller ML, Horta BL. The First National Survey of Indigenous People's Health and Nutrition in Brazil: rationale, methodology, and overview of results. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coimbra C, Jr, Santos R, Escobar A. Epidemiologia e saúde dos povos indígenas no Brasil. Vol. 2013. Rio de Janeiro: Editora FIOCRUZ/ ABRASCO; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cardoso AM, Mattos IE, Koifman RJ. Prevalence of risk factors for cardiovascular disease in the Guaraní-Mbyá population of the State of Rio de Janeiro (in Portugese) Cad Saude Publica. 2001;17:345–354. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2001000200009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agostinho Gimeno SG, Rodrigues D, Pagliaro H, Cano EN, de Souza Lima EE, Baruzzi RG. Metabolic and anthropometric profile of Aruák Indians: Mehináku, Waurá and Yawalapití in the Upper Xingu, Central Brazil, 2000-2002 (in Portugese) Cad Saude Publica. 2007;23:1946–1954. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2007000800021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Capelli JD, Koifman S. Evaluation of the nutritional status of the Parkatêjê indigenous community in Bom Jesus do Tocantins, Pará, Brazil (in Portugese) Cad Saude Publica. 2001;17:433–437. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2001000200018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística . Os indígenas no Censo Demográfico 2010: primeiras considerações com base no quesito cor ou raça. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE; 2012. www.ibge.gov.br/indigenas/indigena_censo2010.pdf (last accessed September 30, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 10. World Obesity Federation World Obesity: About Obesity. www.worldobesity.org/aboutobesity/ (last accessed September 24, 2015).

- 11.Colditz GA, Willett WC, Rotnitzky A, Manson JE. Weight gain as a risk factor for clinical diabetes mellitus in women. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:481–486. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-7-199504010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Magkos F, Mohammed BS, Mittendorfer B. Effect of obesity on the plasma lipoprotein subclass profile in normoglycemic and normolipidemic men and women. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32:1655–1664. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soteriades ES, Hauser R, Kawachi I, Liarokapis D, Christiani DC, Kales SN. Obesity and cardiovascular disease risk factors in firefighters: a prospective cohort study. Obes Res. 2005;13:1756–1763. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calle EE, Kaaks R. Overweight, obesity and cancer: epidemiological evidence and proposed mechanisms. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:579–591. doi: 10.1038/nrc1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nicklas BJ, Penninx BW, Cesari M, Kritchevsky SB, Newman AB, Kanaya AM, Pahor M, Jingzhong D, Harris TB, Health Aging and Body Composition Study Association of visceral adipose tissue with incident myocardial infarction in older men and women. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160:741–749. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Molarius A, Seidell JC. Selection of anthropometric indicators for classification of abdominal fatness - a critical review. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1998;22:719–727. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kragelund C, Omland T. A farewell to body-mass index? Lancet. 2005;366:1589–1591. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67642-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization . Report of a World Health Organization Consultation (WHO Technical Report Series 894) Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. www.who.int/nutrition/publications/obesity/WHO_TRS_894/en/ (last accessed September 24, 2015). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Oliveira GF, de Oliveira TR, Rodrigues FF, Corrêa LF, de Arruda TB, Casulari LA. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in the indigenous population, aged 19 to 69 years, from Jaguapiru Village, Dourados (MS), Brazil. Ethn Dis. 2011;21:301–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. International Diabetes Federation The IDF Consensus Worldwide Definition of the Metabolic Syndrome. www.idf.org/metabolic-syndrome (last accessed September 24, 2015).

- 21.Mancia G, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, Cifkova R, Fagard R, Germano G, Grassi G, Heagerty AM, Kjeldsen SE, Laurent S, et al. Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2007;28:1462–1536. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Diabetes Association Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2012;35((suppl 1)):S64–71. doi: 10.2337/dc12-s064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hosmer D, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. 2 ed. New York: Wiley & Sons; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mahbub Latif AHM, Zakir Hossain M, Islam MA. Model selection using modified akaike's information criterion: an application to maternal morbidity data. Aust J Statist. 2008;37:175–184. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oliveira GF, Oliveira TR, Ikejiri AT, Andraus MP, Galvao TF, Silva MT, Pereira MG. Prevalence of hypertension and associated factors in an indigenous community of central Brazil: a population-based study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e86278. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. IBGE. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística www.ibge.gov.br/home/presidencia/noticias/noticia_visualiza.php?id_noticia=1648&id_pagina=1 (last accessed September 24, 2015).

- 27.Silva DA, Felisbino-Mendes MS, Pimenta AM, Gazzinelli A, Kac G, Velásquez-Meléndez G. Metabolic disorders and adiposity in a rural population (in Portugese) Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2008;52:489–498. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27302008000300009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pérez F, Carrasco E, Santos JL, Calvillán M, Albala C. Prevalence of obesity, hypertension and dyslipidemia in rural aboriginal groups in Chile (in Spanish) Rev Med Chil. 1999;127:1169–1175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gugelmin SA, Santos RV. Human ecology and nutritional anthropometry of adult Xavánte Indians in Mato Grosso, Brazil (in Portugese) Cad Saude Publica. 2001;17:313–322. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2001000200006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saad M. Terena health and nutrition: overweight and obesity (Master dissertation) Campo Grande: Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schulz LO, Bennett PH, Ravussin E, Kidd JR, Kidd KK, Esparza J, Valencia ME. Effects of traditional and western environments on prevalence of type 2 diabetes in Pima Indians in Mexico and the U.S. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1866–1871. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chittleborough CR, Grant JF, Phillips PJ, Taylor AW. The increasing prevalence of diabetes in South Australia: the relationship with population ageing and obesity. Pub Health. 2007;121:92–99. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2006.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deurenberg P, Deurenberg Yap M, Wang J, Lin FP, Schmidt G. The impact of body build on the relationship between body mass index and percent body fat. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999;23:537–542. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.da Rocha AK, Bós AJ, Huttner E, Machado DC. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in indigenous people over 40 years of age in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil (in Portugese) Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2011;29:41–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vedana EH, Peres MA, Neves J, Rocha GC, Longo GZ. Prevalence of obesity and potential causal factors among adults in southern Brazil (in Portugese) Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2008;52:1156–1162. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27302008000700012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dinsa GD, Goryakin Y, Fumagalli E, Suhrcke M. Obesity and socioeconomic status in developing countries: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2012;13:1067–1079. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2012.01017.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oguma Y, Sesso HD, Paffenbarger RS, Lee IM. Weight change and risk of developing type 2 diabetes. Obes Res. 2005;13:945–951. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]