Abstract

Objective

The analysis of the relation between weight loss goals and attrition in the treatment of obesity has produced conflicting results. The aim of the present study was to investigate the role of weight loss goals on attrition in a cohort of obese women seeking treatment at 8 Italian medical centres.

Methods

634 women with obesity, consecutively enrolled in weight loss programmes, were included in the study. Weight loss goals were evaluated with the Goals and Relative Weights Questionnaire (GRWQ), reporting a sequence of unrealistic (‘dream’ and ‘happy’) and more realistic (‘acceptable’ and ‘disappointing’) weight loss goals. Attrition was assessed at 12 months on the basis of patients' medical records.

Results

At 12 months, 205/634 patients (32.3%) had interrupted their programme and were lost to follow-up. After adjustment for age, baseline weight, education and employment status, attrition was significantly associated with higher percent acceptable and disappointing weight loss targets, not with dream and happy weight loss.

Conclusion

In ‘real world’ clinical settings, only realistic expectations might favour attrition whenever too challenging, whereas unrealistic weight loss goals have no effect. Future studies should assess the effect of interventions aimed at coping with too challenging weight goals on attrition.

Key Words: Obesity, Attrition, Weight loss, Cognitive factors, Treatment

Introduction

Attrition is one of the major causes of treatment failure in obesity. Attrition rates range from 10 to 80% in obesity trials [1,2,3,4], and vary from study to study according to type of treatment (drugs, behaviour, bariatric surgery) and experimental design (randomised vs. observational studies). Adherence to weight loss treatments is a key factor of long-term success [5,6]; therefore, effective strategies are needed to reduce the drop-out rates. However, these strategies can only rely on precise identification of factors leading to premature programme termination [7].

In the last 10 years, several studies investigated the relationship between baseline weight loss expectations and attrition in the treatment of obesity, but the results were conflicting. Some studies observed that higher weight loss expectations are associated to attrition [1,5,8,9] while others did not find this relation [10,11,12,13]. The controversy associated to this issue was underlined by a recent review that included the importance of setting realistic goals for weight loss as one of the seven myths about obesity treatment. They concluded that empirical data do not support a positive association between ambitious goals and drop-out [14].

The inconsistency of results on the role of weight loss expectation in attrition seems largely related to the setting where the study is done [15]. In general, clinical trials found that higher weight loss expectations do not increase the risk of attrition [10,11,12,13]. In these settings, however, patients do not pay for treatment, and there is an intensive recall system that may limit the effect of weight loss expectations on attrition. On the contrary, in the ‘real world’ setting, where patients pay for their treatment, higher weight loss expectations have been associated with attrition [1,5,9]. In this setting, not meeting the expectations confronts the patient with the direct and indirect costs of the programme and is very likely to reduce compliance.

The different measures used to assess expectations might be another source of conflicting data across studies. For example, most clinical trials used Part II of the of the Goals and Relative Weights Questionnaire (GRWQ) [13], which assesses the individual's ‘dream’, ‘happy’, ‘acceptable’ and ‘disappointing’ weights, while the QUOVADIS study (QUality of life in Obesity: eVAluation and DIsease Surveillance), a purely observational study on weight loss treatment seeking in ‘real world’, only evaluated a single, less identified expected target, the ‘expected 1-year weight loss with treatment’ [1,5].

The aim of the study was to assess the role of weight loss goals, assessed with GRWQ, Part II [13], in a ‘real world’ clinical setting, not biased by the facilities offered by randomised studies.

Material and Methods

QUOVADIS II Study Planning and Protocol

The QUOVADIS II is a purely observational study on personality, psychological well-being, body image and eating behaviour in obese patients seeking treatment at 8 Italian medical centres (Verona, Milan, Bologna, Ferrara, Florence, Rome) accredited by the Italian Health Service for the treatment of obesity. After enrolment, patients were treated along the lines of the specific programmes of the centres, including dieting, cognitive behavioural therapy and drugs. The results of personality tests, binge eating and night eating have already been reported [16].

634 women with obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2), consecutively seeking treatment at 8 Italian medical centres for the treatment of obesity, were included in the study. All cases were eligible provided they were not on active treatment at the time of enrolment and were in the age range between 25 and 65 years. Patients were excluded if they were pregnant or lactating, took medications affecting body weight, had medical co-morbidities associated with weight loss or had severe psychiatric disorders (e.g., acute psychotic states, bipolar disorder, bulimia nervosa).

The medical record number of the patients was monitored across sites to ensure that patients were truly consecutive.

Data collection included a case report form and a set of questionnaires assessing personality, psychological distress and eating attitudes and behaviours. The protocol was approved by the ethical committees of the individual centres, after initial approval by the ethical committee of the coordinating centre (Azienda Ospedaliera di Bologna, Policlinico S. Orsola - Malpighi). All participants gave written informed consent to participation. The investigation was carried out in accordance with the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Measures

Case Report Form

A medical doctor of every centre filled in the Case Report Form at the time of enrolment by directly interviewing patients.

Weight and Height

Patients' weight and height were measured on a medical balance equipped with a stadiometer. Patients were dressed with underwear without shoes. Weight changes were examined from baseline to 12 months. No data on body weight were collected at 12 months for patients who interrupted treatment. BMI was determined according to the standard formula of body weight (in kg) divided by height (in m2).

Attrition

Attrition was assessed at 12 months by analysing the medical records where the date of the last medical examination and the date when patients were last seen were registered.

Weight Loss Expectations

The part II of the GRWQ [13] was used to assess weight loss goals at the time of enrolment. The questionnaire is a four-item measure assessing the expectations and evaluations of specifically defined weight loss outcomes. Participants write a numerical weight in kg for the following four items: dream weight (a weight you would choose if you could weigh whatever you wish); happy weight (this weight is not as ideal as the first one; it is a weight, however, that you would be happy to achieve); acceptable weight (a weight that you would not be particularly happy with, but one that you could accept, since it is less than your current weight), and disappointing weight (a weight that is less than your current weight, but one that you could not view as successful in any way; you would be disappointed if this were your final weight after the programme).

Statistical Analyses

A first descriptive analysis was used to obtain a qualitative evaluation of clinical data, the response to the GRWQ, part II, and patients' outcomes. The principal outcome variable was attrition (nominal) at 12 months (continuous). ANOVA was used to test the significance of difference between continuers and drop-outs, in relation to the four weight loss goals of GRWQ, part II, at baseline. Correlation analyses were carried out between anthropometric parameters and weight loss goals. Finally, logistic regression analysis was used to identify the role of weight loss needed to achieve the GRWQ goals as determinants of attrition at 12 months, after correction for confounders. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Variables, Attrition and Weight Loss Targets

The large majority of obese women were in the obesity class II and III (table 1), and their clinical characteristics were in keeping with those repeatedly reported in obese women seeking treatment of medical centres in Italy. Their weight loss targets were extremely demanding and significantly correlated with body weight. However, the higher body weight, the larger is the percent amount of weight loss needed to reach the targets of dream (r = 0.650), happy (r = 0.663), acceptable (r = 0.629) and also disappointing weight (r = 0.559) (all p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Demographic and anthropometric characteristics and weight loss targets in women entering a weight loss programme, according to 1-year drop-out a

| Parameter | All cases | Continuers | Drop-out | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 634) | (n = 429) | (n = 205) | ||

| Age, years | 48.0 ± 10.6 | 49.5 ± 10.6 | 44.6 ± 9.9 | <0.001 |

| Weight, kg | 98.1 ± 18.1 | 97.0 ± 17.4 | 100.5 ± 19.4 | 0.022 |

| Height, cm | 161 ± 7 | 161 ± 7 | 161 ± 6 | 0.029 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 37.8 ± 6.6 | 37.5 ± 6.3 | 38.3 ± 7.1 | 0.170 |

| Obesity class (I/II/III), % | 4/35/61 | 5/34/61 | 1/38/61 | 0.067 |

| Weight goals, kg | ||||

| Dream weight | 64.7 ± 8.7 | 64.8 ± 9.0 | 64.4 ± 8.1 | 0.539 |

| Happy weight | 71.6 ± 9.6 | 71.8 ± 9.8 | 71.2 ± 9.4 | 0.441 |

| Acceptable weight | 77.3 ± 11.0 | 77.8 ± 11.3 | 76.3 ± 10.4 | 0.102 |

| Disappointing weight | 85.0 ± 13.5 | 85.7 ± 13.5 | 83.8 ± 13.3 | 0.115 |

| Education, % (95% CI) | 0.559 | |||

| Primary | 12 (9–14) | 13 (9–16) | 11 (7–15) | |

| Secondary | 31 (27–34) | 32 (27–36) | 30 (24–37) | |

| Commercial or vocational | 46 (42–50) | 45 (40–50) | 49 (42–56) | |

| Degree | 12 (10–15) | 13 (10–17) | 10 (6–15) | |

| Employment status, % (95% CI) | <0.001 | |||

| Student | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–3) | |

| Self-employed | 6 (5–8) | 6 (4–9) | 7 (4–11) | |

| Employee | 38 (34–42) | 35 (31–40) | 44 (37–50) | |

| Housewife | 19 (16–22) | 17 (13–20) | 22 (17–28) | |

| Unemployed | 4 (3–6) | 3 (2–5) | 6 (3–10) | |

| Retired | 16 (13–19) | 20 (17–24) | 6 (3–10) | |

| Other | 16 (14–19) | 17 (14–21) | 15 (10–20) |

Data are reported as mean ± SD or as percentage (95% CI)

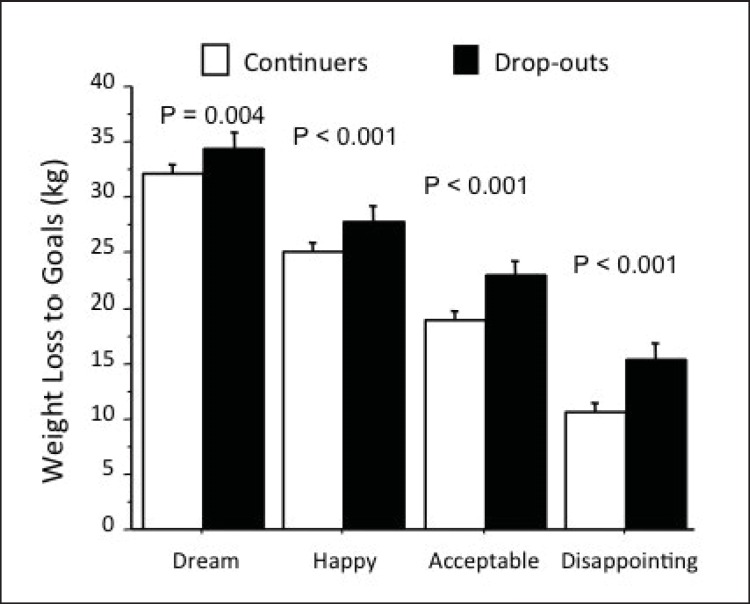

After 12 months, 205 cases (32.3%) were no longer on continuous treatment. Time to drop-out was on average 139 ± 108 days, with 35.8% of all treatment stops occurring within 2 months and 58.8% within 6 months. No differences in age, obesity class and education were observed in relation to attrition. However, baseline BMI was higher in subjects who stopped their weight loss programmes, whereas no systematic differences in weight loss targets were observed. As a result, all weight goals identified by GRWQ implied a larger desired weight loss in drop-outs compared to continuers. In particular (fig. 1), the weight loss to reach dream, happy, acceptable or disappointing goals implied a percent weight loss of 34%, 28%, 23% or 16% in drop-outs, whereas it was 32%, 25%, 19% or 11% in continuers.

Fig. 1.

Weight loss necessary to attain the desired goals in continuers (open bars) and in drop-outs (closed bars). The P values refer to differences between groups.

Body weight at 12 months was 90 ± 16 kg in continuers, corresponding to a percent weight loss of 6.9 ± 6.8%. Weight loss was >10% in 27% of cases, >5% in another 33%. The disappointing weight goal was reached in 36% of cases, the acceptable goal in 12% and the happy goal in 4%, but no cases reached the dream weight goal. In drop-outs, the last observed percent weight loss, available only in 58 cases, averaged 1.6%; it exceed 10% of initial body weight in 7% and was between 5 and 10% in another 14% of cases, with only 7% of cases reaching the disappointing goal threshold.

Weight Loss Targets and Prediction of Attrition

At logistic regression analysis, attrition was associated with higher baseline weight (odds ratio (OR) = 1.11 for 10 kg; 95% confidence interval (95% CI) = 1.01-1.21; p = 0.023) and with younger age (OR = 0.96; 95% CI = 0.94-0.97; p < 0.001). After adjustment for age, baseline weight and employment status, attrition was significantly associated with higher percent weight targets, with the notable exception of dream and happy weight (dream weight: OR = 1.00; 95% CI = 0.98-1.03 for any 1% increase in weight loss to achieve the target of dream weight; p = 0.897; happy weight: OR = 1.02; 95% CI = 0.99-1.04; p = 0.303; acceptable weight: OR = 1.05; 95% CI = 1.02-1.08; p < 0.001; disappointing weight: OR = 1.07; 95% CI = 1.04-1.10; p < 0.001).

Discussion

The study provides robust data on the association between weight loss goals and attrition in a large cohort of obese women seeking weight loss treatment in 8 Italian medical centres. Attrition was associated with more challenging acceptable and disappointing weight targets, but not with dream and happy weights goals. These data confirm previous association between higher weight loss expectations and attrition observed in ‘real world’ settings [1,5,9], and add the original observation that attrition seems mainly influenced by the more realistic but challenging weight goals (i.e., acceptable and disappointing weight) rather than largely unrealistic expectations (i.e., dream and happy weight).

Notably, the association between attrition and weight goals was confirmed in the community when assessed with the same tool (i.e., GRWQ, part II) [13] used in the clinical trials where no association between weight goals and attrition was observed [10,11,12,13]. Therefore, this discrepancy can only be explained by the setting of treatment, but not by the tool used to assess the expected weight goals. As underlined in the Introduction, in clinical trials the impact of weight loss goals on attrition might be concealed by the intensive recall system and by possibility to obtain treatment for free, although less effective than desired. On the contrary, in community settings, where patients pay for any additional contact with therapists, attrition becomes much more likely whenever patients perceive they will never reach their weight goals, but nonetheless they are asked to pay for treatment [1,5,9].

The study provides two more important findings. First, it confirms a previous report showing that obese Italian patients seeking treatment have unrealistic weight loss expectations [17]. They consider barely ‘acceptable’ a weight loss (on average, above 20%) that is more than twice the mean weight usually achieved by lifestyle modification programmes [18], and classify as ‘disappointing’ a weight loss of 10%. A weight loss above 20% is rarely achieved in the community, and also with the most intensive, partly in-hospital programmes and during the firmly controlled conditions of randomised studies this weight loss goal is reached in less than one quarter of cases [19]. Notably, ‘acceptable’ weight goals are frequently much more challenging than the weight loss most of these patients have probably reached in their previous dieting experience [20].

Second, it found an association between attrition and higher baseline weight and younger age. The findings on the relation between age and attrition are conflicting [4]. Weight loss programmes carried out in research settings did not show an association between younger age and treatment discontinuation [2,8,21], while both the QUOVADIS study [1] and another large observational study [22] found that younger age was one the most important predictors of drop-out. We have previously reported that young women are at very high risk of attrition in relation to body image dissatisfaction. This issue was not specifically addressed in the present study. However, a post-hoc analysis showed that weight loss goals were 2-5% lower in women below 45, compared with women above 45, throughout the entire goal spectrum (on average, 35%, 28%, 21%, or 12% in the younger women for dream, happy, acceptable or disappointing goals vs. 31%, 24%, 18%, or 10% in older women; p < 0.05 for all). This strongly supports an important role of body image dissatisfaction in drop-out, as also reported in other studies [8,23].

Conflicting results have been also observed between baseline BMI and attrition. In a 2010 review of the literature, Elfhag et al. [23] found 27 studies where the predicting role of BMI on attrition had been investigated. 18 out of 27 studies failed to demonstrate an association, 5 studies found a positive association between BMI and attrition rate, and 4 reported a lower BMI in subjects who did not complete their weight-reducing programmes [23]. In a previous epidemiological analysis, we reported that subjects entering a weight loss programme have similar expected body weight at 1 year, irrespective of actual body weight, which on average mimics their body weight at the age of 20, i.e., in most cases before the development of frank obesity [24]. This confirms that weight loss goals are much more challenging in subjects with severe obesity, as also observed in the present study, and as such are much more likely to result in drop-out.

The present study had certain strengths. First, it has a good external validity because it assessed the weight loss goals in a large cohort of patients treated in 8 obesity medical centres scattered throughout Italy with heterogeneous modalities of care. Second, it used a gold standard measure of weight goals (i.e., the GRWQ, part II) [13] that allows a comparison with patients' samples treated in different settings and countries. Third, it included a relatively long follow-up time to capture attrition rates in a continuous care model of treatment.

Given its specific aims, the study had some limitations. Firstly, these findings cannot be extended to male patients seeking treatment, and to individuals who seek help in non-medical settings. Second, BMI at time of treatment discontinuation was not systematically recorded. The limited number of data available and the different treatment programmes operated by the centres do not allow to know whether weight goals influence the attrition during the initial weight loss phase or later during the maintenance period after initial intensive treatment. The distribution of days to drop-out in the limited cohort where this value was available indicates that over 50% of treatment stops occurs in the intensive phase. Third, the number of visits of the enrolled subjects was not systematically recorded. This does not permit to assess if the effect of weight loss expectations on attrition was influenced by treatment intensity. Fourth, we did not assess body fat distribution. The result of previous studies produced conflicting results, with one study observing a higher waist-to-hip ratio in non-completers [8] and a second study showing a higher waist circumference in completers [25]. Future studies should assess if body fat distribution - a correlate of body shape that might also reflect body image dissatisfaction -, might play a role in the relationship between weight loss expectations and attrition. Fifth, no information is available about possible changes in weight goals in the course of the treatment programme and how they could influence attrition. Finally, the study did not investigate the role of mediators between expectations and attrition.

The data of the present study have some clinical implications. Clinicians should pay attention to patients' weight loss expectations, in particular to those of the younger patients with higher BMI, and to the acceptable and disappointing weight goals, because they seem to be associated with attrition. Encouraging participants to seek only modest weight loss at the beginning of treatment was not reported as a useful strategy, because it has been associated with lower weight loss than the standard behavioural approach [26]. The negative effect of small early weight loss on treatment outcome has also been reported in two recent studies. In the European multisite DiOGenes study, a smaller weight loss at week 8 was associated with a higher attrition during the subsequent 6-month dietary intervention period [27]; similarly, a higher likelihood of attrition was predicted by small early (week 1) and half-way (week 5) weight losses during a 10-week dietary intervention in the NUGENOB project [28]. Also in the US Look AHEAD trial, the participants who did not lose ≥2% of their initial body weight during the first month of treatment were 5.6 times more likely to fail to reach the 10% weight loss target at 1 year, compared with those who lost ≥2% initially [29]. An effective strategy might be to focus initially on weekly rather than on long-term goals, in order to comply with the need of large early weight losses. This would allow detect and promptly address any warning signs of dissatisfaction, thus minimizing the risk of attrition [17].

Unrealistic weight loss goals may be more easily addressed when patients have successfully reached intermediate weight loss goals, and the rate of weight loss stalls. A few specific strategies and procedures designed to address weight goals have been described in the cognitive behavioural treatment of obesity [30]. According to our clinical experience with subjects with obesity, a trusting and collaborative relationship between physician and patient remains the pivotal issue for treatment success and for promoting a change of unrealistic weight goals. The strategies and procedures to address unrealistic weight loss expectations should be associated with interventions specifically designed to tackle other psychological (e.g., depression, stress) [8,28,31,32] and behavioural variables (e.g., smoking; low level of physical activity; high-fat diet; low total energy, carbohydrate and fibre intake at baseline) that have been associated with higher attrition rates in previous studies [8,28,31].

In conclusion, our study confirms that higher weight loss goals are associated with attrition in obese women seeking treatment in a ‘real world’ setting. Future research should investigate the factors mediating weight loss expectation and attrition, the effect of interventions aimed at addressing unrealistic weight goals on attrition and if spontaneous longitudinal changes in weight goals could influence attrition.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interests in relation to the material presented in this manuscript.

References

- 1.Dalle Grave R, Calugi S, Molinari E, Petroni ML, Bondi M, Compare A, et al. Weight loss expectations in obese patients and treatment attrition: an observational multicenter study. Obes Res. 2005;13:1961–1969. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inelmen EM, Toffanello ED, Enzi G, Gasparini G, Miotto F, Sergi G, et al. Predictors of drop-out in overweight and obese outpatients. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005;29:122–128. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennett GA, Jones SE. Dropping out of treatment for obesity. J Psychosom Res. 1986;30:567–573. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(86)90029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moroshko I, Brennan L, O'Brien P. Predictors of dropout in weight loss interventions: a systematic review of the literature. Obes Rev. 2011;12:912–934. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dalle Grave R, Melchionda N, Calugi S, Centis E, Tufano A, Fatati G, et al. Continuous care in the treatment of obesity: an observational multicentre study. J Intern Med. 2005;258:265–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2005.01524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perri MG, Sears SF, Jr, Clark JE. Strategies for improving maintenance of weight loss. Toward a continuous care model of obesity management. Diabetes Care. 1993;16:200–209. doi: 10.2337/diacare.16.1.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grossi E, Dalle Grave R, Mannucci E, Molinari E, Compare A, Cuzzolaro M, et al. Complexity of attrition in the treatment of obesity: clues from a structured telephone interview. Int J Obes. 2006;30:1132–1137. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teixeira PJ, Going SB, Houtkooper LB, Cussler EC, Metcalfe LL, Blew RM, et al. Pretreatment predictors of attrition and successful weight management in women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28:1124–1133. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ames GE, Thomas CS, Patel RH, McMullen JS, Lutes LD. Should providers encourage realistic weight expectations and satisfaction with lost weight in commercial weight loss programs? A preliminary study. Springerplus. 2014;3:477. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-3-477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fabricatore AN, Wadden TA, Womble LG, Sarwer DB, Berkowitz RI, Foster GD, et al. The role of patients' expectations and goals in the behavioral and pharmacological treatment of obesity. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31:1739–1745. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Linde JA, Jeffery RW, Finch EA, Ng DM, Rothman AJ. Are unrealistic weight loss goals associated with outcomes for overweight women? Obes Res. 2004;12:569–576. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Linde JA, Jeffery RW, Levy RL, Pronk NP, Boyle RG. Weight loss goals and treatment outcomes among overweight men and women enrolled in a weight loss trial. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005;29:1002–1005. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foster GD, Wadden TA, Vogt RA, Brewer G. What is a reasonable weight loss? Patients' expectations and evaluations of obesity treatment outcomes. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65:79–85. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Casazza K, Fontaine KR, Astrup A, Birch LL, Brown AW, Bohan Brown MM, et al. Myths, presumptions, and facts about obesity. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:446–454. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1208051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dalle Grave R, Calugi S, Marchesini G. The influence of cognitive factors in the treatment of obesity: lessons from the QUOVADIS study. Behav Res Ther. 2014;63C:157–161. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dalle Grave R, Calugi S, Marchesini G, Beck-Peccoz P, Bosello O, Compare A, et al. Personality features of obese women in relation to binge eating and night eating. Psychiatry Res. 2013;207:86–91. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dalle Grave R, Calugi S, Magri F, Cuzzolaro M, Dall'Aglio E, Lucchin L, et al. Weight loss expectations in obese patients seeking treatment at medical centers. Obes Res. 2004;12:2005–2012. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wadden TA, Foster GD. Behavioral treatment of obesity. Med Clin North Am. 2000;84:441–461. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(05)70230-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dalle Grave R, Calugi S, Gavasso I, El Ghoch M, Marchesini G. A randomized trial of energy-restricted high-protein versus high-carbohydrate, low-fat diet in morbid obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013;21:1774–1781. doi: 10.1002/oby.20320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marchesini G, Cuzzolaro M, Mannucci E, Dalle Grave R, Gennaro M, Tomasi F, et al. Weight cycling in treatment-seeking obese persons: data from the QUOVADIS study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28:1456–1462. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perri MG, McAdoo WG, Spevak PA, Newlin DB. Effect of a multicomponent maintenance program on long-term weight loss. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1984;52:480–481. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.52.3.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Honas JJ, Early JL, Frederickson DD, O'Brien MS. Predictors of attrition in a large clinic-based weight-loss program. Obes Res. 2003;11:888–894. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elfhag K, Rossner S. Initial weight loss is the best predictor for success in obesity treatment and sociodemographic liabilities increase risk for drop-out. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;79:361–366. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Melchionda N, Marchesini G, Apolone G, Cuzzolaro M, Mannucci E, Grossi E, et al. The QUOVADIS study. Features of obese Italian patients seeking treatment at specialist centers. Diabetes Nutr Metab. 2003;16:115–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Inelmen EM, Toffanello ED, Enzi G, Gasparini G, Miotto F, Sergi G, et al. Predictors of drop-out in overweight and obese outpatients. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2005;29:122–128. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Foster GD, Phelan S, Wadden TA, Gill D, Ermold J, Didie E. Promoting more modest weight losses: a pilot study. Obes Res. 2004;12:1271–1277. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Handjieva-Darlenska T, Handjiev S, Larsen TM, van Baak MA, Lindroos A, Papadaki A, et al. Predictors of weight loss maintenance and attrition during a 6-month dietary intervention period: results from the DiOGenes study. Clin Obes. 2011;1:62–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-8111.2011.00010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Handjieva-Darlenska T, Holst C, Grau K, Blaak E, Martinez JA, Oppert JM, et al. Clinical correlates of weight loss and attrition during a 10-week dietary intervention study: results from the NUGENOB project. Obes Facts. 2012;5:928–936. doi: 10.1159/000345951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Unick JL, Hogan PE, Neiberg RH, Cheskin LJ, Dutton GR, Evans-Hudnall G, et al. Evaluation of early weight loss thresholds for identifying nonresponders to an intensive lifestyle intervention. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2014;22:1608–1616. doi: 10.1002/oby.20777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cooper Z, Fairburn CG, Hawker DM. A Clinician's Guide. New York: Guilford Press; 2003. Cognitive Behavioral Treatment of Obesity. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clark MM, Niaura R, King TK, Pera V. Depression, smoking, activity level, and health status: pretreatment predictors of attrition in obesity treatment. Addict Behav. 1996;21:509–513. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(95)00081-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wadden TA, Foster GD, Letizia KA. Response of obese binge eaters to treatment by behavior therapy combined with very low calorie diet. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1992;60:808–811. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.5.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]