Abstract

Objective

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a rare, autoimmune disease characterised by endothelial dysfunction, which is associated with peripheral vasculopathy, such as digital ulcers (DU). We sought to determine if acute oral administration of tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4), an essential cofactor for endothelial nitric oxide synthase, would augment endothelial function in patients with SSc.

Methods

Twelve SSc patients, of whom a majority had a history of DU, were studied 5 hours after oral BH4 administration (10 mg/kg body weight) or placebo on separate days using controlled, counterbalanced, double-blind, crossover experimental design.

Results

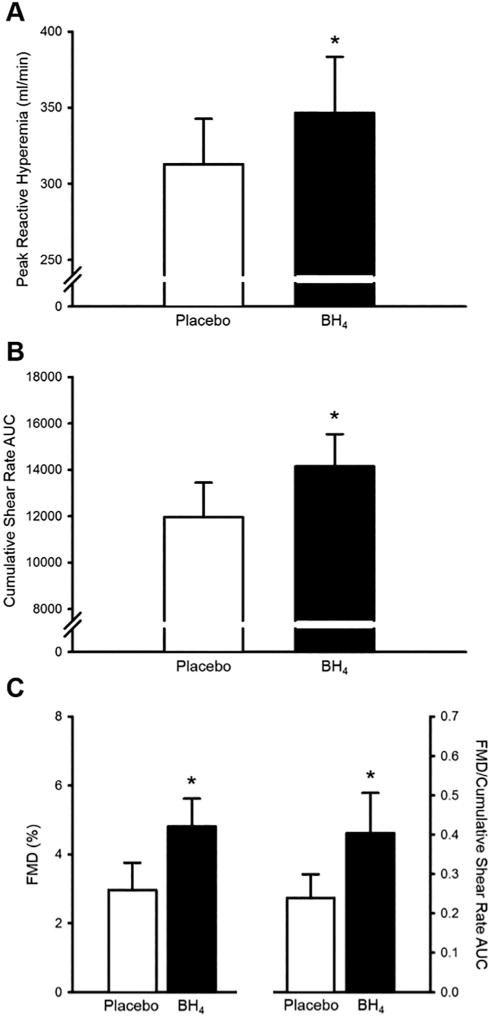

There were no differences in blood markers of oxidative stress and brachial artery blood pressure, diameter, blood velocity, shear rate, or blood flow at rest between placebo and BH4 (p>0.05). Whereas, after a 5 minute suprasystolic forearm cuff occlusion, brachial artery peak reactive hyperemia (placebo: 313±30 vs. BH4: 347±37 ml/min, p<0.05) and flow-mediated dilation (FMD) (placebo: 3.0±0.8 vs. BH4: 4.8±0.8%, p<0.05) were significantly higher after acute BH4 administration, indicating an improvement in endothelial function. To determine if the vasodilatory effects of BH4 were specific to the vascular endothelium, brachial artery blood flow and vasodilation in response to sublingual nitroglycerin were assessed, and were found to be unaffected by BH4 (p>0.05).

Conclusion

These findings indicate that acute BH4 administration ameliorates endothelial dysfunction in patients with SSc. Given that endothelial dysfunction is known to be associated with DU in SSc patients, this study provides a proof-of-concept for the potential therapeutic benefits of BH4 in the prevention or treatment of DU in this population.

Keywords: systemic sclerosis, vascular, endothelium

Introduction

Systemic sclerosis (SSc, scleroderma) is a rare multi-organ, autoimmune disease that results in progressive fibrosis and vasculopathy (1). Despite considerable heterogeneity in organ involvement, it is well accepted that vascular abnormalities are present in nearly all patients and that eventual vascular injury may lead to fibro-proliferative vasculopathy and tissue fibrosis in SSc (2). A recent meta-analysis has reported impaired vascular endothelial function in patients with SSc using the endothelium-dependent, flow-mediated dilation (FMD) technique, which is the gold standard, noninvasive method for quantifying nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability (3). Silva et al. recently reported that FMD and other biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction are predictive of digital ulcers (DU) (4, 5). Our work supports that endothelial dysfunction in SSc, measured by FMD, is associated with peripheral vasculopathy (i.e., DU) (6). Taken together, these studies imply that the link between a dysfunctional endothelium and peripheral vasculopathy in SSc can be effectively measured.

An insufficient endothelial bioavailability of tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) may be partly responsible for endothelial dysfunction in SSc. BH4 is an essential cofactor for endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) that is critical for maintaining NO bioavailability in the vascular endothelium (7, 8). When the endothelial concentration of BH4 is insufficient, eNOS becomes “uncoupled” and pro-2ces superoxide, rather than NO, resulting in elevated oxidative stress and lower NO bioavailability (9). We have recently reported that elevated oxidative stress in SSc patients is accompanied by endothelial dysfunction (10). Therefore, if the primary event in SSc vascular abnormalities is endothelial dysfunction due to lower NO bioavailability as a result of insufficient BH4, with the subsequent development of fibro-proliferative vasculopathy and tissue fibrosis, then improving NO bioavailability may have a preventative role (2). Therefore, we sought to examine vascular endothelial function after acute oral BH4 administration in SSc patients. We hypothesised that, compared to placebo, acute BH4 administration would augment vascular endothelial function in patients with SSc.

Materials and methods

Study participants

Twelve patients with SSc were recruited from the University of Utah SSc Clinic to participate in this study. Patients were previously diagnosed with SSc, by 2013 classification criteria (11), and given that we previously have reported a link between endothelial function and DU, there was an effort to recruit patients with a history of DU. All procedures were approved by the institutional review board of the University of Utah and Salt Lake City VAMC, which serves as the ethics committee. Written informed consent was obtained prior to participation after an explanation of the nature, benefits, and risks of the study.

Participant characteristics

Body mass index (BMI) was calculated from height and body mass. Clinical features of patients with SSc were recorded for modified Rodnan skin score (mRSS), cardiovascular-acting medications, SSc and Raynaud’s phenomenon (RP) duration, history of SSc-related vasculopathy including pulmonary arterial hypertension, scleroderma renal crisis, and/or DU, antinuclear antibody, and SSc-specific antibody status. None of the participants had diabetes mellitus or met criteria for another overlapping inflammatory rheumatic disease.

Experimental design

A controlled, counter-balanced, double-blind, crossover experimental design with two conditions, BH4 and placebo, was employed. There was a washout period of at least 5 days before crossing over into the alternate condition. On the experimental days, patients reported to the laboratory after having consumed a standardized breakfast and oral BH4 (10mg/kg) or placebo five hours prior to their arrival. All measurements were taken at the same time of day to eliminate any diurnal effects. All participants abstained from alcohol, caffeine, and exercise for ≥12 hours prior to the study. Additionally, vasodilatory medications were discontinued 12 hours prior to study visit. In premenopausal women, measurements were performed during the early follicular phase of the menstrual cycle. All measurements were made under quiet, comfortable, ambient (~22°C) laboratory conditions.

Blood pressure

Brachial arterial blood pressure measurements were made with a semi-automated BP device (Tango+, SunTech, Morrisville, NC) in triplicate after 5 min in the upright seated position (12) and after 10 min in the supine position (10).

Flow-mediated dilation

Endothelium-dependent dilation was assessed noninvasively with the FMD technique using a 5-min suprasystolic occlusion period, as described previously (13) and in accordance with recently published guidelines (14). Briefly, a blood pressure cuff was placed on the right arm, distal to the ultrasound Doppler probe on the brachial artery. The same investigator was used for all FMD measurements Simultaneous measurements of brachial artery vessel diameter and blood velocity were performed using a linear array transducer operating in duplex mode, with imaging frequency of 14 MHz and Doppler frequency of 5 MHz (Logic 7, GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI). All measurements were obtained with the probe appropriately positioned to maintain an insonation angle of ≤60°. The sample volume was maximized according to vessel size and was centered within the vessel on the basis of real-time ultrasound visualization. The brachial artery was insonated approximately midway between the antecubital and axillary regions, and measurements of diameter and blood velocity were obtained continuously at rest and for 2 minutes after cuff deflation. Enddiastolic, ECG R-wave-gated images were collected via video output from the Logic 7 for off-line analysis of brachial artery vasodilation using automated edge-detection software (Medical Imaging Application, Coralville, IA). Heart rate was monitored from a standard 3-lead ECG. FMD was quantified as the maximal change in brachial artery diameter after cuff release. FMD is expressed as a percent increase in diameter from rest. Shear rate was calculated according to the equation: shear rate (s−1) = blood velocity · 8/vessel diameter. Forearm blood flow was calculated as per the equation: forearm blood flow (ml/min) = (blood velocity · π · [vessel diameter/2]2 · 60). Cumulative shear rate (area under the curve, AUC) at the time of peak brachial artery vasodilation was determined using the trapezoidal rule, as described previously (15). The same investigator (DRM) performed and analyzed FMD measurements in all patients.

Endothelium-independent dilation

When not contraindicated due to medication usage, endothelium-independent dilation (EID) was assessed non-invasively by sublingual nitroglycerin (0.8 mg) in a subset of patients (n=5). EID was determined ≥60 min after FMD measurement with the brachial artery insonated in the same position as during FMD measurement. Measurements of diameter and blood velocity were obtained continuously at rest and for 5 min after administration of sublingual nitroglycerin. EID was quantified as the maximal change in brachial artery diameter, expressed as a percent increase in diameter from rest. The same investigator (DRM) performed and analyzed EID measurements in all patients.

Oxidative stress, antioxidant capacity, and inflammation assays

Blood samples were obtained from the antecubital patients with SSc. Serum and plasma samples were stored at −80°C until analysis. Oxidative stress was assessed by quantifying plasma malondialdehyde (MDA) (Oxis Research/Percipio Bioscience, Foster City, CA) and protein carbonyl levels (Northwest Life Science Specialties, LLC Vancouver, WA). Endogenous antioxidant capacity, assessed by superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT) activity, were assayed in the plasma (16) (Cayman Chemical Company, Ann Arbor, MI). Additionally, total antioxidant capacity was assessed by measuring the ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP), using the method described by Benzie and Strain (17). Systemic inflammation was assessed by determining IL-6, TNF-α (18) and C-reactive protein (CRP) in serum (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

Statistical analysis

Power calculations were performed using G*Power computer software version 3 (19). The α-level used for power analysis was set at 0.05. Sample-size calculations were based on the number of patients needed to detect significant differences in FMD between placebo and BH4 (20, 21). With 12 patients/group we had >95% power to detect differences in FMD between placebo and BH4. Statistics were performed using SPSS software (IBM, Chicago, IL). Paired t-tests were used to identify significant changes in measured variables between placebo and BH4. To determine if an effect of visit order was present, the difference in BH4 vs. placebo was calculated and patients were separated into groups based on order of conditions. Unpaired t-tests were used to identify significant changes in measured variables between ordered groups. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05 for all analyses. Data are presented as mean±SEM.

Results

Clinical characteristics

The clinical characteristics of the SSc patients are presented in Table I. Among patients with SSc the duration of SSc for first non-RP symptom ranged from 1–36 years. A majority of the SSc patients (58%) had a history of DU. There was no effect of BH4 administration on brachial artery systolic (placebo: 115±4 vs. BH4: 115±4 mmHg, p>0.05) and diastolic (placebo: 72±3 vs. BH4: 73±2 mmHg, P>0.05) blood pressure measured in the casual seated position. Plasma markers of oxidative stress, antioxidant capacity, and inflammation were unchanged between placebo and BH4 conditions (p>0.05; Table II).

Table I.

Subject characteristics.

| Variables | Value |

|---|---|

| Women:men, n | 9:3 |

| Age, years | 62 ± 3 |

| Height, cm | 169 ± 3 |

| Weight, kg | 68.2 ± 2.7 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.8 ± 0.7 |

| mRSS | 3.8 ± 0.7 |

| Medications, % | |

| Calcium channel blockers | 11 (92) |

| Angiotensin II receptor antagonists | 0 (0) |

| ACE inhibitors | 0 (0) |

| Endothelin receptor antagonists | 0 (0) |

| Phosphodiesterase inhibitors | 1 (8) |

| SSc duration, years | 8.4 ± 2.9 |

| RP duration, years | 9.8 ± 3.0 |

| Vasculopathy history, n (%) | |

| Pulmonary arterial hypertension | 1 (8) |

| SSc renal crisis | 1 (8) |

| Digital ulcers | 7 (58) |

| Antibody presence, n (%) | |

| Centromere | 7 (58) |

| RNA polymerase III | 1 (8) |

| SCL70 | 2 (17) |

| Fibrillin | 2 (17) |

| RNP | 1 (8) |

Values are presented as mean ± SEM.

BMI: body mass index, mRSS: modified Rodnan skin score, RP: Raynaud’s phenomenon, SSc: systemic sclerosis.

Table II.

Blood oxidative stress, antioxidant status, and inflammatory markers.

| Variables | Placebo | BH4 |

|---|---|---|

| MDA, μM | 2.8 ± 0.1 | 2.9 ± 0.2 |

| Protein carbonyl, nM/mg | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 0.16 ± 0.01 |

| CAT, nM/min/mL | 86 ± 7 | 78 ± 11 |

| FRAP, nM/L | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.2 |

| SOD, U/mL | 10.7 ± 0.6 | 11.1 ± 1.3 |

| IL-6, pg/mL | 1.3 ± 0.5 | 1.4 ± 0.5 |

| TNF-α, pg/mL | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.2 |

| CRP, mg/L | 3.2 ± 0.7 | 3.1 ± 0.6 |

Values are mean±SEM.

There were no significant differences between placebo and BH4 administration.

MDA: malondialdehyde; CAT: catalase; FRAP: ferric reducing ability of plasma; SOD: superoxide dismutase; IL: interleukin; CRP: C-reactive protein.

Effects of BH4 on brachial artery vascular function

In the supine resting position prior to cuff occlusion, heart rate and brachial artery blood pressure, diameter, blood velocity, shear rate, and blood flow were unchanged between placebo and BH4 conditions (p>0.05; Table III). After a 5 minute suprasystolic cuff occlusion, peak reactive hyperemia and cumulative shear rate AUC at peak dilation were significantly higher after acute BH4 administration (p<0.05; Fig. 1A and 1B). Brachial artery FMD and FMD normalized to cumulative shear rate AUC at peak dilation were significantly higher after acute BH4 administration (p<0.05; Fig. 1C). In response to sublingual nitroglycerin administration, there were no differences in peak brachial artery blood flow (placebo: 31±3 vs. BH4: 30±2%, p>0.05) or EID (placebo: 26±2 vs. BH4: 26±2 ml/min, p>0.05) between placebo and BH4 conditions. There was no effect of visit order on any measurement (p>0.05).

Table III.

Cardiovascular variables at rest.

| Variables | Placebo | BH4 |

|---|---|---|

| Heart rate, bpm | 68 ± 3 | 68 ± 3 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 114 ± 3 | 111 ± 5 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg, | 71 ± 2 | 69 ± 2 |

| Diameter, mm | 3.79 ± 0.20 | 3.78 ± 0.21 |

| Blood velocity, cm/sec | 4.4 ± 0.6 | 4.5 ± 0.4 |

| Shear rate, s−1 | 95 ± 12 | 100 ± 13 |

| Blood flow, ml/min | 32 ± 7 | 30 ± 3 |

Values are mean±SEM.

There were no significant differences between placebo and BH4 administration.

Fig. 1.

Brachial artery peak reactive hyperemia (A) cumulative shear rate area under the curve (AUC) at peak dilation (B), and flow-mediated dilation (FMD) (C, left) were significantly higher after acute tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) administration in patients with systemic sclerosis (SSc). Because the magnitude of FMD is dependent on accumulation of shear stress until to peak dilation, FMD was normalised to cumulative shear rate AUC at peak dilation, and was found to be significantly higher after acute BH4 administration (C, right). *p<0.05 vs. placebo. Values are mean±SEM.

Discussion

Our results indicate that acute oral BH4 administration improves endothelial function in patients with SSc. The main findings are that, compared to placebo, BH4 administration in patients with SSc augments brachial arterial post-ischemic peak reactive hyperemia, cumulative shear rate AUC at peak dilation, and FMD. Because the magnitude of FMD is dependent on its shear stimulus, we normalized FMD to the cumulative shear rate AUC at peak dilation. We found that FMD normalized its shear stimulus was also augmented after acute BH4 administration, which provides more evidence that the BH4-related increase in FMD was due to an improvement vascular endothelial function. In support of this, we observed no change in EID, demonstrating that the effects of BH4 administration were likely to be specific to the vascular endothelium. Lastly, we observed no changes in blood markers of oxidative stress, antioxidant status, or inflammation after BH4 administration, providing evidence that BH4-related improvements in FMD were due to elevated BH4 bioavailability and not a change in redox status. Taken together, these findings indicate that acute BH4 administration ameliorates endothelial dysfunction in patients with SSc. Importantly, given that the majority of patients in this study had a history of DU, and that endothelial dysfunction is associated with and predictive of DU (4–6), these findings provide a proof-of-concept for the therapeutic potential of BH4 in prevention and treatment of DU.

The effects of BH4 on vascular function in SSc

In addition to conduit arterial endothelial dysfunction (i.e., impaired FMD), patients with SSc also have resistance arterial vasodilatory dysfunction, demonstrated by an impairment in brachial artery reactive hyperemia (6) and exercise-induced hyperemia (22). Interestingly, we observed improvements in post-ischemic peak reactive hyperemia and cumulative shear rate AUC at peak dilation after BH4 administration in the present study. However, the BH4-mediated improvement in peak reactive hyperemia was considerably lower than the magnitude of difference from healthy controls that we reported previously (6). Although there is considerable debate as to the degree to which myogenic, neural, or local factors play a role in the reactive hyperemic response to ischemia, NO does appear to marginally impact reactive hyperemia (23–25). Therefore, it is possible that the slight, but significant increase in peak reactive hyperemia after BH4 administration is due to a BH4–mediated improvement in NO bioavailability. Moreover, we observed no difference in blood flow between conditions during EID measurement. Given that resistance arterial vasodilation governs the increase in blood flow through the brachial artery, these results suggest that augmented peripheral hemodynamics after acute BH4 administration were not likely due to improvements in resistance arterial EID.

In the present study, we found that acute oral BH4 administration augments endothelial function in patients with SSc. This finding was demonstrated by an improvement in FMD after BH4, and is in agreement with others that have reported improved FMD after acute oral BH4 administration in the elderly (20), smokers (21), and patients with rheumatoid arthritis (22). Because we observed a BH4-mediated improvement in cumulative shear rate AUC at peak dilation, which is the stimulus for FMD (26), we normalized FMD to the cumulative shear rate AUC at peak dilation. We found that FMD normalized to its shear stimulus was also augmented after acute BH4 administration, indicating a greater sensitivity of the endothelium to changes in shear rate. Of note, the improvement in normalized FMD after BH4 administration in the present study surpassed the magnitude of impairment in normalized FMD between patients with SSc and age- and sex-matched healthy controls from our previous study (6), suggesting that acute oral BH4 administration may restore endothelial function in patients with SSc.

Clinical implications of BH4 in SSc

In SSc patients, endothelial dysfunction is associated with and predictive of DU (4, 6). Thus, in the present study, there was a concerted effort to recruit SSc patients with a history of DU, as we hypothesized they would be more likely to have endothelial dysfunction and possess a greater BH4-mediated improvement in FMD. Although the entire study population did not have a history of DU, the majority did, and the improvements in endothelial function after acute BH4 administration imply a beneficial effect of BH4 in SSc patients with a history of DU. Whether endothelial dysfunction is predictive of DU is largely unexplored, however, given that a history of DU is a risk factor for future DU (27), improvements in endothelial function in patients with DU history may indicate the therapeutic potential of BH4 in prevention of DU in these patients.

Our findings show that acute BH4 administration improves endothelial function in patients with SSc. Of course, whether improvements in endothelial function can be maintained with chronic BH4 administration in this population is unknown. Vaudo et al. reported that one week of oral BH4 supplementation maintained the improvement in FMD in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (28), while others have shown improvements in endothelial function after 4–8 weeks of BH4 supplementation in hypercholesterolemic and hypertensive individuals (29, 30). Of note, no adverse effects of BH4 were found in these studies. Although chronic BH4 supplementation studies in patients with SSc are yet to be completed, future study is warranted.

There were no effects of acute BH4 administration on blood pressure in patients with SSc. Although it should be noted that acute BH4 administration lowers blood pressure in hypertensive individuals (30), hypotensive effects have not been reported in other populations (20–22, 30, 31). Thus, the improvements in endothelial function after BH4 administration appear to be independent of blood pressure in normotensive individuals. This is important because the standard of care for treatment of SSc- and RP-related resistance arterial vasodilatory dysfunction are smooth muscle vasodilatory drugs, which augment blood flow, but also have hypotensive effects (32). With any hypotensive drug there is increased risk of orthostatic intolerance, which underscores the importance for any adjunct therapy to smooth muscle vasodilators to not affect blood pressure. Therefore, the lack of a hypotensive effect with BH4 increases its potential for use as adjunct therapy to smooth muscle vasodilatory drugs in SSc.

Mechanistic insights into improvements in endothelial function with BH4

We have recently shown that vascular endothelial dysfunction in SSc is accompanied by elevated oxidative stress and attenuated antioxidant capacity (10). In the present study, we observed improvements in conduit artery endothelial function and resistance artery vasodilatory function after acute BH4 administration, yet blood markers of oxidative stress and antioxidant status were unaffected by BH4 administration. An insufficient endothelial concentration of BH4 results in “uncoupled” eNOS that no longer produces NO, but rather produces superoxide (9). Thus, these vascular improvements are likely due to BH4-mediated recoupling of eNOS in endothelial cells, rather than a change in vascular redox status. There is no evidence that acute BH4 administration lowers oxidative stress, however, chronic BH4 administration has been reported to attenuate oxidative damage in hypercholesterolemia (29). Therefore, while it is possible that chronic BH4 consumption may reduce oxidative stress, thereby reducing the accumulation of oxidative damage, however, this scenario is unlikely to be present after acute BH4 administration.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our results indicate that acute oral BH4 administration ameliorates endothelial dysfunction in patients with SSc. The improvement in endothelial function after BH4 administration was likely due to an increase in endothelial BH4 bioavailability, as we observed no changes in EID or blood markers of oxidative stress or inflammation to account for the observed improvements. Considering the relatively small sample size of 12 SSc patients in the present study, these findings provide a proof-of-concept for the therapeutic use of BH4 in SSc patients. Moreover, improvements in endothelial function after BH4 administration occurred in a cohort SSc patients of whom the majority had a history of DU, which provides a promising therapeutic potential of BH4 in prevention and treatment of DU.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by awards from the National Institutes of Health (R01 AG040297, R01 HL118313, P01 HL091830, R21 AG043952, K23AR067889, and K02 AG045339) and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (I01 RX001697 and I01 CX001183). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Competing interests: none declared.

References

- 1.FRECH TM, REVELO MP, DRAKOS SG, et al. Vascular leak is a central feature in the pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 2012;39:1385–91. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.111380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.ASANO Y, SATO S. Vasculopathy in scleroderma. Semin Immunopathol. 2015;37:489–500. doi: 10.1007/s00281-015-0505-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MEISZTERICS Z, TIMAR O, GASZNER B, et al. Early morphologic and functional changes of atherosclerosis in systemic sclerosis-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology. 2016;55:2119–30. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kew236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DA SILVA IF, TEIXEIRA A, OLIVEIRA J, ALMEIDA R, VASCONCELOS C. Endothelial dysfunction, microvascular damage and ischemic peripheral vasculopathy in systemic sclerosis. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2017 Jan 17; doi: 10.3233/CH-150044. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.SILVA I, TEIXEIRA A, OLIVEIRA J, ALMEIDA I, ALMEIDA R, VASCONCELOS C. Predictive value of vascular disease biomarkers for digital ulcers in systemic sclerosis patients. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2015;33:S127–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.FRECH T, WALKER AE, BARRETT-O’KEEFE Z, et al. Systemic sclerosis induces pronounced peripheral vascular dysfunction characterized by blunted peripheral vasoreactivity and endothelial dysfunction. Clin Rheumatol. 2015;34:905–13. doi: 10.1007/s10067-014-2834-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.COSENTINO F, LUSCHER TF. Tetrahydrobiopterin and endothelial function. Eur Heart J. 1998;19(Suppl G):G3–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MONCADA S, PALMER RM, HIGGS EA. Nitric oxide: physiology, pathophysiology, and pharmacology. Pharmacol Rev. 1991;43:109–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.WEVER RM, VAN DAMT, VAN RIJNHJ, DE GROOT F, RABELINK TJ. Tetrahydrobiopterin regulates superoxide and nitric oxide generation by recombinant endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;237:340–4. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MACHIN DR, CLIFTON HL, GARTEN RS, et al. Exercise-induced brachial artery blood flow and vascular function is impaired in systemic sclerosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2016;311:H1375–H81. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00547.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.VAN DEN HOOGEN F, KHANNA D, FRANSEN J, et al. 2013 classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: an American College of Rheumatology/European League against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:2737–47. doi: 10.1002/art.38098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MACHIN DR, PARK W, ALKATAN M, MOUTON M, TANAKA H. Hypotensive effects of solitary addition of conventional nonfat dairy products to the routine diet: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100:80–7. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.085761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.HARRIS RA, NISHIYAMA SK, WRAY DW, TEDJASAPUTRA V, BAILEY DM, RICHARDSON RS. The effect of oral antioxidants on brachial artery flow-mediated dilation following 5 and 10 min of ischemia. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2009;107:445–53. doi: 10.1007/s00421-009-1147-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.HARRIS RA, NISHIYAMA SK, WRAY DW, RICHARDSON RS. Ultrasound assessment of flow-mediated dilation. Hypertension. 2010;55:1075–85. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.150821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.NISHIYAMA SK, WALTER WRAYD, BERKSTRESSER K, RAMASWAMY M, RICHARDSON RS. Limb-specific differences in flow-mediated dilation: the role of shear rate. J Appl Physiol. 2007;103:843–51. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00273.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.WHEELER CR, SALZMAN JA, ELSAYED NM, OMAYE ST, KORTE DW., JR Automated assays for superoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione peroxidase, and glutathione reductase activity. Anal Biochem. 1990;184:193–9. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(90)90668-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.BENZIE IF, STRAIN JJ. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of “antioxidant power”: the FRAP assay. Anal Biochem. 1996;239:70–6. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.CHEN X, XUN K, CHEN L, WANG Y. TNF-alpha, a potent lipid metabolism regulator. Cell Biochem Funct. 2009;27:407–16. doi: 10.1002/cbf.1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.FAUL F, ERDFELDER E, LANG AG, BUCHNER A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39:175–91. doi: 10.3758/bf03193146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.ESKURZA I, MYERBURGH LA, KAHN ZD, SEALS DR. Tetrahydrobiopterin augments endothelium-dependent dilatation in sedentary but not in habitually exercising older adults. J Physiol. 2005;568:1057–65. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.092734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.UEDA S, MATSUOKA H, MIYAZAKI H, USUI M, OKUDA S, IMAIZUMI T. Tetrahydrobiopterin restores endothelial function in long-term smokers. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:71–5. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00523-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MAKI-PETAJA KM, DAY L, CHERIYAN J, et al. Tetrahydrobiopterin Supplementation Improves Endothelial Function But Does Not Alter Aortic Stiffness in Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DAKAK N, HUSAIN S, MULCAHY D, et al. Contribution of nitric oxide to reactive hyperemia: impact of endothelial dysfunction. Hypertension. 1998;32:9–15. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.32.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.CRECELIUS AR, RICHARDS JC, LUCKASEN GJ, LARSON DG, DINENNO FA. Reactive hyperemia occurs via activation of inwardly rectifying potassium channels and Na+/K+-ATPase in humans. Circ Res. 2013;113:1023–32. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.301675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.ENGELKE KA, HALLIWILL JR, PROCTOR DN, DIETZ NM, JOYNER MJ. Contribution of nitric oxide and prostaglandins to reactive hyperemia in human forearm. J Appl Physiol. 1996;81:1807–14. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.4.1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.PYKE KE, TSCHAKOVSKY ME. Peak vs total reactive hyperemia: which determines the magnitude of flow-mediated dilation? J Appl Physiol. 2007;102:1510–9. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01024.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.CUTOLO M, HERRICK AL, DISTLER O, et al. Nailfold Videocapillaroscopic Features and Other Clinical Risk Factors for Digital Ulcers in Systemic Sclerosis: A Multicenter, Prospective Cohort Study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:2527–39. doi: 10.1002/art.39718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.VAUDO G, MARCHESI S, GERLI R, et al. Endothelial dysfunction in young patients with rheumatoid arthritis and low disease activity. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:31–5. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.007740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.COSENTINO F, HURLIMANN D, DELLI GATTI C, et al. Chronic treatment with tetrahydrobiopterin reverses endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress in hypercholesterolaemia. Heart. 2008;94:487–92. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.122184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.PORKERT M, SHER S, REDDY U, et al. Tetrahydrobiopterin: a novel antihypertensive therapy. J Hum Hypertens. 2008;22:401–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1002329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.HIGASHI Y, SASAKI S, NAKAGAWA K, et al. Tetrahydrobiopterin improves aging-related impairment of endothelium-dependent vasodilation through increase in nitric oxide production. Atherosclerosis. 2006;186:390–5. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.LEROY EC, MEDSGER TA., JR Criteria for the classification of early systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:1573–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]