Highlights

-

•

Choledocholithiasis may present as many as 33 years after a patient has undergone a cholecystectomy.

-

•

Potential etiologies of choledocholithiasis after cholecystectomy include surgical clip migration, remnant cystic duct lithiasis, and primary choledocholithiasis.

-

•

Choledocholithiasis is rare after a patient has undergone a cholecystectomy, but must be ruled out nevertheless.

Keywords: Case report, Choledocolithiasis, Cholecystectomy, Surgical clip migration

Abstract

Introduction

Choledocholithiasis after cholecystectomy is rare and often attributed to surgical clip migration and subsequent nidus formation.

Presentation of case

This case demonstrates choledocholithiasis following cholecystectomy with a latency period of 33 years.

Discussion

The patient presented with pain of the right upper quadrant (RUQ). Subsequent abdominal-pelvic CT imaging revealed dilation of the common bile duct. Further Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography was indicative of choledocholithiasis. Additional findings included a long cystic duct remnant and surgical clips in the RUQ.

Conclusion

The patient underwent biliary sphincterotomy and sludge and stone fragments were swept from the biliary tree. To our knowledge, a latency of 33 years between cholecystectomy and choledocholithiasis has never been reported before, at least not in a patient without coexisting duodenal diverticulum, a condition associated with lithiasis of the common bile duct. Our case raises discussion of potential etiologies for such long latency, including surgical clip migration, remnant cystic duct lithiasis, and primary choledocholithiasis; and further details the incidence of such long latency periods following cholecystectomy

1. Introduction

Cholecystectomy is one of the most commonly performed surgeries in the United States.

Post-cholecystectomy choledocolithiasis is a rare occurrence and presentation has been reported over a wide range of time following surgery, from one year to as many as twenty years [2], [5], [7], [8]. In the following case, the patient was found to have choledocholithiasis 33 years after her cholecystectomy. This is the longest reported latency in choledocholithiasis following cholecystectomy in a patient without coexisting peri-ampullary diverticulum [12]. This case was handled at an academic institution and the case report has been presented in accordance with the SCARE criteria [1].

Presentation of case

The patient is a 57-year-old African American female with past medical history of hypertension and remote surgical history of cholecystectomy 33 years prior, who presented to another medical center with non-radiating sharp RUQ pain. The patient rated the pain as a 7 out of 10 and experienced associated nausea and vomiting and one episode of fever (102°F) with reduced appetite for two days prior to admittance. Initial laboratory tests were notable for WBC 13.500, AST 514 U/L, ALT 379 U/L, total bilirubin (TB) 2.7 mg/dl, lipase 497 U/L.

Abdominal-pelvic computed tomography (CT) imaging revealed a dilated common bile duct (CBD) of 2.2 centimeters with intrahepatic dilation and a prominent head of the pancreas. Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography confirmed the dilation of the CBD with distal tapering and showed a small volume of fluid around the liver and the CBD suggestive of cholangitis. The patient was started on IV broad spectrum antibiotics. Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was performed and a protruding, swollen, enlarged ampulla with polypoid changes in the 2nd part of duodenum and localized attenuation of the bile duct were identified. A sphincterotomy was performed with copious biliary drainage. However, stent placement was unsuccessful.

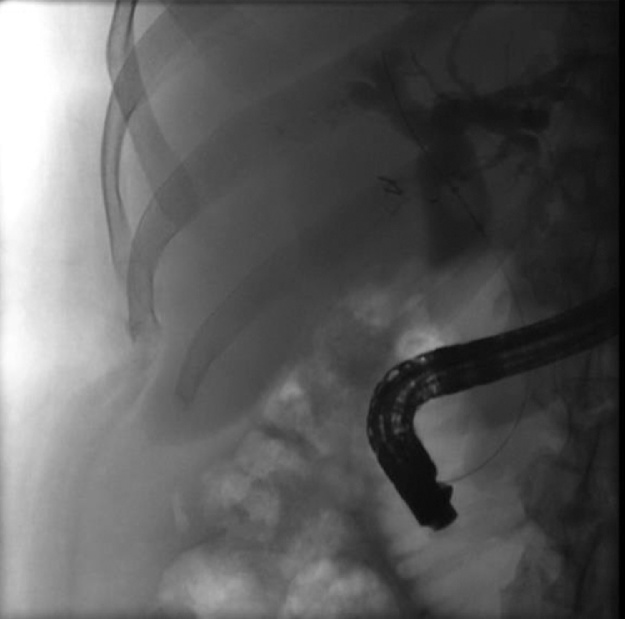

The patient was then transferred to our medical center afebrile and hemodynamically stable. Repeat laboratory tests were notable for WBC 13,300, TB 1.8 mg/dl, ALK 228 U/L, AST 46 U/L, ALT 128 U/L, lipase 36 U/L. The prior biliary endoscopic sphincterotomy appeared open at repeat ERCP done by our GI endoscopist (BG). The cholangiogram showed that the left main hepatic duct, right main hepatic duct, common bile duct and common hepatic duct were moderately dilated. A filling defect consistent with a stone was seen on the cholangiogram. There was also a low lying cystic duct and long cystic duct remnant (Fig. 1). The biliary tree was swept and a trans-papillary dilation was performed. Sludge and stone fragments were removed. It was unclear if the stone fragments were completely removed, therefore a 10Fr × 7 cm plastic stent was placed into the common bile duct.

Fig. 1.

ERCP image indicating dilation of left and right main hepatic ducts and common bile duct, consistent with choledocholithiasis.

Subsequent double helical and pelvis contrast CT returned no findings of pancreatic head mass. Tumor markers (CEA, CA 125 and CA 19.9) were all found to be within normal limits.

The patient was discharged home on hospital day 4, after tolerating full enteral intake and after normalization of WBC, bilirubin, and lipase levels.

The biliary stent was endoscopically (ERCP) removed two months later without complications in an outpatient setting (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

ERCP image taken during stent removal indicating resolution of biliary obstruction.

Discussion

Surgical clip migration has been widely reported as a cause for similar late post-cholecystectomy choledocolithiasis [2], [3], [5], [7], [10], [11]. This kind of late post-operative complication was first reported in 1979 [3], [10] and attributed to a surgical clip migration and its subsequent role as a nidus for stone formation. In addition to surgical clip migration, remnant cystic duct lithiasis (RCDL) has been cited as a cause of recurring symptoms following surgery [6]. Cystic duct lithiasis often goes unidentified by pre-operative imaging via both ultrasound and CT [9]. The long cystic duct remnant noted during imaging further contributes to the possibility of RCDL, given that this would increase the area over which a remnant lithiasis may have been missed during the original operation.

The ideal length of the cystic duct remnant that could virtually eliminate the risk of primary cystic duct lithiasis is still to be debated. However, the non-secreatory nature of the cystic duct makes the likelihood of primary cystic duct lithiasis quite unlikely and hence the cause of cystic duct lithiasis secondary to clip migration the more likely explanation for the findings presented with our case.

The mean interval between surgery and discovery of RCDL in a study of twelve patients was 34.2 months [6], while clip migration time has been reported to vary between 11 and 20 years [8]. The most common ductal stones in the United States are secondary stones, those that migrate into the CBD via the cystic duct [4]. However, primary stones of the CBD have also been reported and cannot be ruled out in this case. These may originate intra-hepatically or within the CBD. They are thought to occur due to bacterial infections of the bile ducts and are attributed to biliary stasis and abnormalities of the sphincter of Oddi [4].

Prior sphincterotomy and periampullary diverticulum are also known conditions that have been associated with choledocholithiasis after cholecystectomy [13], [14]. Food and debris can make their way into the bile duct leading to biliary obstruction and/or lead to nidus formation in this kind of setting. Neither one of these conditions seem to have played a role in our case.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the second case reported in the literature [12] with a latency of over 30 years between cholecystectomy and presentation of CBD lithiasis. This extreme latency in presentation importantly highlights possibilities of post-cholecystectomy bile duct stones and the need to acknowledge the potential for such late presentations even in patients who have undergone cholecystectomies, thus reducing the propensity for secondary stones within the bile ducts. This case serves as an addition to the existing literature regarding post-cholecystectomy choledocholithiasis and further exemplifies the possible extent of latency in their presentation. Though we do not report the longest latency within the literature, we aim to provide another case of extreme latency to further enumerate the incidence of these cases in the hopes that a greater understanding and documentation of their etiology will follow. Given the uncertain cause of this presentation, and similar post-operative complications reported in the literature, it is important to identify potential contributors to these late presentations and proactively address them.

Conflicts of interest

The Authors declare no conflicts of interest pertinent to this case report.

Funding

No source of funding to be declared.

Ethical approval

No Institutional Review Board is required for publication of a case report at our institution.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contribution

Study Concept and Design: A. Gangemi

Data Collection: A Gangemi, B. Gannavarapu

Writing of Paper: X. Peters, A. Gangemi, B. Gannavarapu

References

- 1.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saetta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P., SCARE Group The SCARE Statement: Consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pernas Canadell J.C. Choledochal lithiasis and stenosis secondary to the migration of a surgical clip. Radiologia. 2014;56(6):e46–e49. doi: 10.1016/j.rx.2012.03.006. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cookson N.E., Mirnezami R., Ziprin P. Acute cholangitis following intraductal migration of surgical clips 10 years after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Case Reports in Gastrointestinal Medicine. 2015;2015:5. doi: 10.1155/2015/504295. 50429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Copelan A., Baljendra K.S. Choledocholithiasis: diagnosis and management. Tech. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2015;18(4):244–255. doi: 10.1053/j.tvir.2015.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gonzalez F.J., Dominguez E., Lede A., Portela J., Miguel P. Migration of vessel clip into the common bile duct and late formation of choledocholithiasis after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Am. J. Surg. 2011;202(4):e41–e43. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Phillips M.R., Joseph M., Dellon E.S., Grimm I., Farrel T.M., Rupp C.C. Surgical and endoscopic management of remnant cystic duct lithiasis after cholecystectomy—a case series. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18(7):1278–1283. doi: 10.1007/s11605-014-2530-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rajendra A., Cohen S.A., Kasmin F.E., Siegel J.H. Surgical clip migration and stone formation in gallbladder remnant after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2009;70(4):780–781. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rawal K.K. Migration of surgical clips into the common bile duct after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Case Reports in Gastroenterology. 2017;10(3):787–792. doi: 10.1159/000453658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sezeur A., Akel K. Cystic duct remnant calculi after cholecystectomy. Journal of Visceral Surgery. 2011;148(4):e287–e290. doi: 10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh M.K., Kinder K.Z., Braverman S.E. Transhepatic management of a migrated intraductal surgical clip after cholecystectomy and gastrectomy. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2015;26(12):1866. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2015.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walker W.E., Avant G.R., Reynolds V.H. Cholangitis with a silver lining. Arch. Surg. 1979;114(2):214–215. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1979.01370260104019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marinella M. Choledocholithiasis causing obstructive jaundice 52 years after cholecystectomy. JAGS. 1995;43(11):1318–1319. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb07416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ando T., Tsuyuguchi T., Okugawa T. Risk factors for recurrent bile duct stones after endoscopic papillotomy. Gut. 2003;52(1):116–121. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.1.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pereira-Lima J.C., Jakobs R., Winter U.H. Long-term results (7–10 years) of endoscopic papillotomy for choledocholithiasis. Multivariate analysis of prognostic factors for the recurrence of biliary symptoms. Gastrointest. Endosc. 1998;48:457–464. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(98)70085-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]