Abstract

Growing evidence exists on the potential for adapting evidence-based interventions for low- and-middle-income countries (LMIC). One opportunity that has received limited attention is the adaptation of psychotherapies developed in high-income countries (HIC) based on principles from LMIC cultural groups. Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) is one such treatment with significant potential for acceptability in South Asian settings with high suicide rates. We describe a tri-phasic approach to adapt DBT in Nepal that consists of qualitative interviews with major Nepali mental health stakeholders (Study 1), an adaptation workshop with 15 Nepali counselors (Study 2), and a small-scale treatment pilot with eligible clients in one rural district (Study 3). Due to low literacy levels, distinct conceptualizations of mind and body, and program adherence barriers, numerous adaptations were required. DBT concepts attributable to Asian belief systems were least comprehensible to clients. However, the 82% program completion rate suggests utility of a structured, skills-based treatment. This adaptation process informs future research regarding the effectiveness of culturally adapted DBT in South Asia.

Keywords: Dialectical behavior therapy, suicide, cultural adaptation, Nepal, global mental health

Suicide and suicidal behavior are serious global public health concerns (World Health Organization [WHO], 2014). Suicide is among the 10 leading causes of death in many countries, and for every incident of completed suicide, there are an estimated 20 attempts. In 2012 alone, over 800,000 people died of suicide internationally, representing a global mortality rate of 11.4 people per 100,000, or approximately one death every 40 seconds. Of these deaths, the majority occur in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC), resulting in significant economic, social, and psychological strain at individual, community, and national levels.

In Nepal, suicide accounts for 16% of all deaths among Nepali women of childbearing age, making it the number-one cause of mortality in this demographic (Suvedi et al., 2009). Despite the noted significance of this finding, it has received scant attention in the form of targeted intervention. In Nepal, suicide is primarily managed via law enforcement, whose main role is documentation, and emergency health services that address attempts such as ingesting pesticides (Hagaman, Maharjan & Kohrt, 2016). For those who emergency care, few are referred to psychological or psychiatric services.

Current activities to prevent suicide have increased since the 2015 earthquakes, with programs including establishment of a suicide prevention hotline. Programmatic efforts by local nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and international collaborators to integrate mental health care into primary care settings are also currently underway (Jordans, Luitel, Pokharel, & Patel, 2016), and raising suicide awareness among health workers is often a component of these programs. However, the impacts of these efforts on suicide have not been specifically evaluated.

Although comprehensive, evidence-based interventions (EBIs) for suicide and self-harm exist, they are not frequently deployed in LMIC settings like Nepal (WHO, 2014). When implemented, they have primarily targeted reduction in diagnostic symptoms of mood disorders and posttraumatic stress, rather than self-destructive behaviors. Further, the majority of these interventions have failed to consistently account for a client’s unique cultural values and norms (Bernal, Jiménez-Chafey & Domenech Rodríguez, 2009). In response to increased recognition of cultural influences within the treatment process, psychotherapy adaptations that attend closely to the role of culture are rapidly expanding (Castro, Barrera, & Steiker, 2010). This is particularly significant for suicide, because interventions must address a complex web of social, personal, and historical factors. At the time of study initiation, however, there were no systematic attempts at adapting EBIs for suicide in Nepal.

Historical and Emerging Guidelines for Cultural Adaptation

Processes for cultural adaptation, which vary widely with regard to the original treatments being adapted and the target populations, can be loosely categorized into three domains. The first of these approaches includes adaptations that are manifold, nonempirical in nature, and largely based on subjective clinical encounters and experiences (Hwang, 2006). Adaptations in this domain are often rooted in moral decrees, namely that unique cultural values and competencies are significant and demand respect, regardless of their context. This adaptation modality is decreasingly invoked because of concern regarding the deleterious impacts that haphazard or inappropriate adaptations can have on the fidelity and effectiveness of interventions.

Recent approaches to cultural adaptation, in contrast, are increasingly systematic, with clear, conceptual frameworks that propose content suggestions for determining when and how interventions should be modified (e.g., Hwang, 2006; Lau, 2006). A third domain—stage models— have also been proposed for cultural adaptation of interventions. A crucial aspect of these stage models is the inclusion of deliberate and specific steps to guide data collection to determine the need for cultural adaptation, intervention components that require modification, and preliminary effectiveness of modifications. Of these guidelines, a majority are iterative and process-driven, incorporating multiple manual revisions and various stages of feedback from clients and clinicians (e.g., Kumpfer, Pinyuchon, de Melo, & Whiteside, 2008; Wingood & DiClemente, 2008). In other frameworks, top-down approaches to adaptation are complemented by community engagement and participation, resulting in a process model for adaptation that incorporates frequent user, provider, and community-level feedback (e.g., Domenech Rodriguez & Wieling, 2004).

Form and Structure of Cultural Adaptations

The theoretical underpinnings supporting cultural adaptations of EBIs are rich and varied. One pragmatic orientation conceives of successful adaptations as existing between two oppositional extremes (Benish, Quintana, & Wampold, 2011). On one end of the spectrum lie exclusively Western models of psychotherapy, which are evidence-based, abundant, and recognized as universally pliable. The opposing end contains the grounded theory model, which roots itself in the belief that a maximally efficacious adaptation is (a) constructivist by nature; (b) designed with one specific ethnocultural population in mind; and (c) nongeneralizable outside of its specific development context. An effective adaptation may exist between these two poles. A number of studies (e.g., Hinton et al., 2005; Van Loon, van Schaik, Dekker, & Beekman, 2013) have followed this middle-ground approach, which ensures fidelity to an evidence-based therapy while still allowing for inclusion of culturally salient elements.

For cultural adaptations in LMIC international settings, efforts must also address the paucity of trained mental health professionals in these settings (Patel, 2009). A growing body of literature in global mental health advocates for the role of task-sharing, or the involvement of nonspecialists with limited-to-no prior background in mental health service delivery in care provision. Therefore, in addition to modifying treatment design and content, international adaptations have also emphasized novel training and supervision requirements to encourage delivery by nonspecialists or lay providers. In one program for perinatally depressed Pakistani mothers and their infants (Rahman et al., 2008), basic CBT principles were simplified in order to encourage skillful delivery by local female health workers. Studies utilizing task-sharing are flourishing in LMIC, with trials in Uganda (e.g., Bolton et al., 2003; Singla, Kumbakumba & Aboud, 2015) and India (e.g., Chowdhary et al., 2015; Patel et al., 2010), among many others.

Objective

In this study, we sought to culturally adapt and pilot a Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT: Linehan, 1993a) program for reducing suicidal behaviors in a rural, resource-poor Nepali setting. DBT was selected for several reasons, the first being that it is an empirically supported therapy targeting self-destructive behaviors. Given the high suicide prevalence in Nepal, DBT had the potential to fill an essential public health need. Second, DBT emphasizes a flexible, contextual, and principle-driven view of behaviors (Hayes, Villatte, Levin, & Hildebrandt, 2011). Delivery of DBT requires tailoring of techniques or strategies to the client’s unique circumstances; because of this inherent flexibility, it was considered ideal for cultural modification with ethnic Nepalis. Third, DBT’s emphasis on teaching practical, real-world skills via group setting allowed for development of a manualized protocol for use by lay Nepali counselors with no prior education or training in the treatment. Fourth, DBT explicitly integrates Zen Buddhist principles, mindfulness, and acceptance into treatment. Its conceptualization of clients and events using these Buddhist perspectives had the theoretical potential to align with Nepali ethnopsychological1 divisions of the mind, body, and self (Kohrt & Harper, 2008). Lastly, DBT’s behavioral emphasis on treating underlying processes of emotion dysregulation provided an advantage in allowing us to circumvent the need to treat according to DSM-defined diagnostic categories, which are demonstrated to have high levels of comorbidity and limited distinctions in LMIC studies (e.g., Bolton, Surkan, Gray, & Desmousseaux, 2012).

This study describes the first cultural adaptation of an empirically supported intervention for suicidal behaviors in a low-resource, international setting. The primary goal was to identify and incorporate culturally salient adaptations to an existing intervention to reduce emotion regulation–related distress in suicidal and self-harming Nepali women. Consistent with common adaptation approaches for minority groups (e.g., Baumann, Domenech Rodríguez, Amador, Forgatch, & Parra-Cardona, 2014; Domenech Rodriguez & Wieling, 2004), our adaptation involved an iterative and collaborative process based on in-depth interviews with mental health stakeholders, an adaptation workshop with Nepali mental health professionals, and a pilot of the intervention in rural Nepal with women exhibiting suicidal behaviors. This study is innovative in its objective to back-adapt a Western, evidence-based psychological treatment with roots in Asian cultural tenets to a LMIC context.

Methods

The overall study was conducted as a combined series of three smaller studies, each informing design and development of the next. Research culminated in development of a 5-day training curriculum and manualized protocol for training and dissemination of DBT for Nepali populations (DBT-N). The study received approval by Duke University’s Institutional Review Board (Pro00052917) and the Nepal Health Research Council. The research was conducted in collaboration with Transcultural Psychosocial Organization (TPO) Nepal, a research-oriented organization based in Kathmandu.

Study 1: Stakeholder Interviews

In-depth interviews with professional and paraprofessional mental health-care providers were conducted to explore attitudes towards treatment of suicidal and self-harming clients, risk factors underlying the onset and severity of emotion dysregulation symptoms, salient domains for treatment adaptation, and barriers to delivery of DBT in Nepal.

Study Participants

Twelve participants with current or prior exposure to suicidal or self-harming clientele were selected from four groups: respected religious (Buddhist and Hindu) leaders, psychosocial counselors, psychiatrists, and traditional healers. These groups were selected to maximize variability in clinical expertise and utilized treatment modalities.

Qualitative Instrument Development

Interview guides were developed for each four participant groups identified above. Interviews explored basic processes of recruitment, engagement, and retention in care for suicidal and self-harming clients; participants’ experiences treating such clients; external and internal prompting events; attempted treatment strategies and their potential utility; community perceptions towards suicide; and salient metaphors describing difficulties in emotion regulation. Each semistructured guide was piloted with two researchers at TPO-Nepal, with minor revisions made for clarity and flow.

Data Collection and Analysis

Interviews were digitally recorded and underwent Nepali–English translation and written transcription. They were then analyzed using a constant comparative method of data analysis. This method consisted of (a) reading each transcript multiple times for content, then (b) open-coding an interview transcript for data on key themes surrounding suicide and self-harm in Nepal. This iterative process was applied to remaining transcripts until a final set of themes emerged. Interview results guided the DBT adaptation process for both curriculum and manual development in Studies 2 and 3, respectively.

Study 2: Adaptation Workshop With Nepali Mental Health Professionals

In Study 2, a 5-day DBT adaptation workshop was conducted with a cohort of TPO-employed counselors in Kathmandu. The workshop was facilitated by three members of the study team, including (a) a clinical psychologist trained in the U.S. with over 5 years of clinical experience in DBT, also a Nepali citizen bilingual in Nepali and English; (b) an American cultural psychiatrist and medical anthropologist with two decades of experience working with ethnic Nepalis in both Nepal and the U.S., and (c) a South Asian–American master’s-level researcher with foundational training in DBT. Data from Studies 1 and 2 were then used to inform development of a preliminary DBT-N manual for use in Study 3.

Participant Recruitment

A total of 15 psychosocial providers from Kathmandu and surrounding districts participated in this portion of the study. All counselors had at least six months of psychosocial training, and had been delivering psychotherapy for a minimum of 5 years. Fourteen of the participants were counselors with over 1 year of prior training, and one was a social worker at a collaborating NGO. All participants were actively engaged in clinical work, including one-on-one contact with suicidal and self-harming clients, and were versed in basic principles of cognitive behavioral treatment.

Workshop Curriculum Development and Piloting

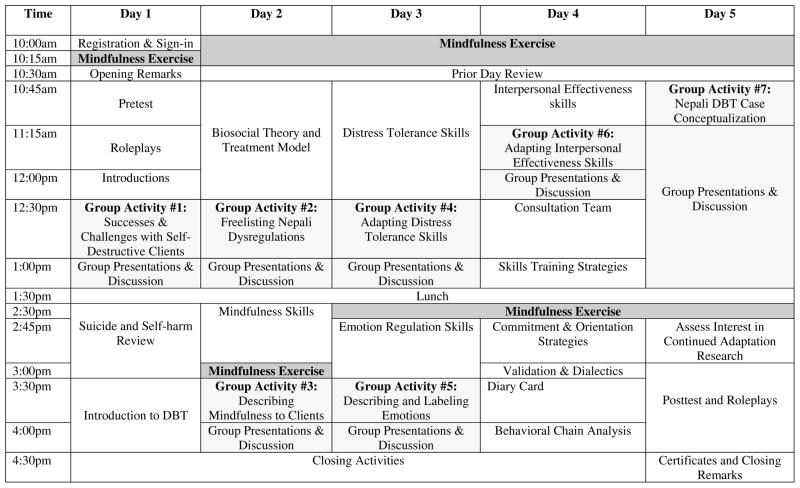

Workshop materials were developed using (a) the initial version of the Dialectical Behavior Therapy Skills Training Manual (Linehan, 1993b); (b) a modified, time-limited (12-week) DBT group structured for survivors of domestic violence (Iverson, Shenk, & Fruzzetti, 2009); and (c) qualitative data from Study 1. The workshop mirrored a traditional skills training group, with added didactics on the biosocial theory of emotion dysregulation, treatment hierarchies and prioritization, screening methods for suicide and nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI), and behavioral chain analysis. It also incorporated small group activities (see Figure 1), in which one facilitator and four to five participants collaborated to adapt one or more components of the standard DBT regimen and was followed by individual group presentations and group discussion. This discussion was used to make further adaptations to skills training content and related exercises.

Figure 1.

5-day DBT-N Adaptation Workshop Schedule

Data Collection and Analysis

Following Nepali–English transcription and translation, workshop transcripts were analyzed using qualitative methodology identical to that outlined in Study 1. Results from workshop analyses were used to guide further development and modification of the DBT-N manual.

Study 3: Process Analysis of DBT-N Pilot

Manual Development

An initial DBT-N treatment manual was developed using a combination of (a) qualitative research from Studies 1 and 2; (b) literature-based adaptation frameworks (e.g., Barrera & Castro, 2006; Baumann et al., 2014); (c) prior research on Nepali ethnopsychology (e.g., Kohrt & Harper, 2008); and (d) DBT skills training manuals (Fruzzetti & Erikson, 2011; Linehan, 1993b). The manualized program incorporated all four DBT modules, with the addition of a validation module to target nonacceptance, self-blame and criticism, and stigma encountered by suicidal clients from family members, peers, and local communities. Throughout the intervention, the manual was dynamically adjusted to account for novel outcomes in skills uptake and comprehension.

To simplify manual content, each session had a corresponding 5- to 11-page facilitation section to aid therapists, a one-page list of session objectives, and a schedule. This objectives list included both a list of required skills review and materials. In order to provide additional guidance for newly trained counselors, content also included sample role-plays, skills training scripts, and handout explanations. Handouts were laminated, and clients were encouraged to place them on home walls to promote skills generalization. Sessions concluded with homework assignment and diary card dissemination. Manual materials were designed to be flexibly tailored using counselor and client feedback after each session.

Participant Recruitment

Purposive sampling was used to recruit 10 women of reproductive age (18–45). Clients were eligible for DBT-N if they (a) received a score of 1 or greater on Item 9 of the culturally and clinically validated Nepali version of the Beck Depression Inventory (Kohrt, Kunz, Koirala, Sharma & Nepal, 2002); and (b) had attempted suicide or engaged in intentional self-injury at least once within the past two years. Women with evidence of developmental disabilities, substance abuse, and/or psychosis were excluded. The intervention was provided at no financial cost to participants.

Intervention Procedures

DBT-N consisted of 10 sessions of weekly group therapy, each lasting approximately three hours. There were two group leaders: one study team member (MKR) and a local counselor who participated in the Study 2 workshop. An expert DBT trainer with extensive training and supervisory experience (CJR) and a US-trained clinical psychologist of Nepali origin with an active DBT clinical practice (DF) provided weekly and ad-hoc remote supervision as needed. All sessions, with the exception of the initial meeting, began with a group mindfulness exercise, followed by a behavioral chain analysis. Skill-specific didactics and experiential activities for one of the five DBT-N modules (Mindfulness, Distress Tolerance, Self-Validation, Emotion Regulation, and Interpersonal Effectiveness) followed. Each session concluded with homework assignment and skills generalization strategies.

Results

Study 1: Findings and Adaptations to Study 2 and DBT-N Manual

In-depth interviews resulted in five areas of adaptation (see Table 1):

Table 1.

List of Adaptation Considerations From Study 1 and Applications to Training and Dissemination

| Suicide and Self-Harm Related Factors | Application to Workshop Curriculum | Application to DBT-N Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Relationship between interpersonal conflict and impulse control deficits |

|

|

| Lack of validated diagnostic criteria for Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) in Nepal |

|

|

| Low linkage and adherence to care |

|

|

| Internalized and community stigma |

|

|

| Chronic deficits in emotion regulation skills |

|

|

High Prevalence of Interpersonal Conflict

All respondents indicated that self-destructive behaviors were often triggered by interpersonal conflicts, ranging from chronic disputes with husbands and in-laws to brief and stigmatized, inter-caste relations that resulted in intense, internalized shame for women. Maltreatment by mothers-in-law and inter-case marriage have also been identified as risk factors for mental health distress in Nepal (Adhikari et al., 2014; Kohrt & Worthman, 2009). Elements of physical, emotional, and psychological violence were also found, suggesting utility of a manual designed specifically for female victims of domestic violence. Further, all respondents linked issues with interpersonal conflict with poor impulse control behaviors.

Accordingly, culturally consonant role-plays highlighting relationship discord were included in the DBT-N manual. Safety plans were incorporated into the curriculum to account for Nepali attitudes toward marital separation and familial integration.

Cultural Concerns Regarding Acceptability of Borderline Personality Disorder Diagnoses

Instead of focusing on borderline personality disorder, for which multiple (n = 5) interviewees cited a lack of research on prevalence, etiology, or presentation on in Nepal, we emphasized DBT’s transdiagnostic potential by highlighting its effectiveness in treating a wide range of emotional disorders and maladaptive behaviors. Many of the Nepali counselors in Study 2 had prior clinical exposure to and had successfully managed this range of problems.

Lack of Access and Limited Adherence to Mental Health Care

All participants cited difficulties in treating self-destructive clients, largely due to barriers in adequate client engagement and retention. Increasing migration rates were also contributors to infrequent or short-lived client-provider interactions.

In response, we included myths related to retention and successful treatment of suicidal and self-harming clients in our training curriculum and expanded our model of case conceptualization to include aspects such as entry and engagement into care. Counselors brainstormed strategies to address these structural barriers in the Study 2 workshop.

Internalized and Community Stigma

All participants indicated that, in Nepal, suicide is considered a crime and is cloaked in irreversible stigma for both victims and their families. Individuals with prior attempts were viewed as having reduced potential for marriage, and, along with relatives, were likely to face discrimination in social and economic sectors. Local ethnopsychological models consider suicide to result from an imbalance or dysfunction of the dimaag (brain-mind), the rational apparatus that governs cognitions as well as proper social functioning (Kohrt, Maharjan, Timsina, & Griffith, 2012). Since dimaag-related problems are considered severe and permanent, they are often associated with profound stigma (Kohrt & Harper, 2008). One participant, a member of the indigenous Buddhist group, explained his religious community’s belief in the phenomenon of suicide contagion, whereby exposure to a suicide-related death influences others (who may or may not already be at risk) to similarly take their lives.

To avoid reinforcement of stigmatizing stereotypes and behaviors among providers and community members, we incorporated a section on dispelling common suicide and self-harm myths into the workshop curriculum. For the DBT-N, we described DBT skills to clients and family members as relevant and applicable to anyone, regardless of mental health status, in order to avoid negative treatment perceptions.

Chronic Coping Skills Deficits

Seven providers specifically identified skills deficits as major contributors to self-destructive behaviors. Through case studies elicited in interviews, we conceptualized skills-related barriers as inabilities to reduce or modulate intense emotional reactions, which align with emotion-regulated problems targeted by DBT. Prior research on counseling in Nepal has also strongly emphasized the cultural appeal of skills training in psychological treatments (Tol, Jordans, Regmi, & Sharma, 2005). We therefore prioritized didactics on group skills training in the workshop, and included multiple small group activities to culturally adapt module-specific skills. In the DBT-N manual, we standardized weekly skills training across manual variations.

Study 2: Workshop Findings and Adaptations to DBT-N Manual

Fifteen participants completed the workshop, for a 100% retention rate over the 5-day period. The average age for participants was 33.3 years (SD = 6.57). Two-thirds were women. All participants had a minimum of a bachelor’s-level education and were currently active as mental health or psychosocial providers in one or more of four Nepali districts represented. Higher caste Bahun and Chhetri groups predominated (66.7%), with no representation from the lower Dalit/Nepali caste.

Findings from the 5-day workshop informed further development and modification of the DBT-N program. Six domains of adaptation were identified (see Table 2):

Table 2.

List of Second Wave of Adaptations Following Study 2 Workshop

| Adaptation Domain | Description | Key Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Language | Identification of culturally syntonic Nepali counterparts to standard DBT terminology |

|

| Sociodemographics | Population characterization using key sociodemographic indicators (religion, education, economic status, literacy level) |

|

| Culturally consonant metaphors and imagery | Incorporation of Nepali-specific representations of DBT skills, theories, and concepts |

|

| Skills training content | Culturally appropriate organization, presentation, and delivery of skills and associated exercises |

|

| Vulnerability factors | Identification of individual and community-level stressors in rural Nepal |

|

| Ethnopsychology | Incorporation of Nepali conceptualizations of affect, cognitions, social connections, and the self |

|

| Linkage and retention | Identification of feasible treatment delivery formats |

|

Language

Workshop activities were a rich source of language equivalents. During adaptation of Interpersonal Effectiveness skills (Group Activity 6; see Figure 1), participants expressed difficulties comprehending the term “self-respect.” Directing the sentiment to oneself was considered foreign and inappropriate, whereas respect for others (aruharulaai adhaar garne) was common and salient.

In response, we sought Nepali corollaries for DBT-specific terminology with adequate comprehensibility, acceptability, and semantic equivalence. For instance, accurate, nonstigmatizing translations for mindfulness (sachetansilata) and wise mind (buddhi mani soch) were incorporated into the DBT-N manual. Specific discussion of self-respect was also omitted in the manual, which instead emphasized action in accordance with personal and interpersonal values.

Sociodemographic Variables

In the final day, group members were asked to construct a case conceptualization using a former or current client (Figure 1: Group Activity 7). Considerations included (a) linkage and commitment to care; (b) self-destructive triggers and related urges; (c) process of therapy (group vs. individual, hierarchical targeting, specific exercises); (d) strategies for skills generalization for illiterate clientele; and (e) therapy-interfering behaviors and countering strategies. All participants identified the need to modify text-based DBT diary cards and homework assignments with meaningful equivalents for illiterate or low-literacy clientele. Two groups chose to highlight the value of interpersonal and universal connectedness with clients, primarily through use of Buddhist cosmology.

Adaptations in this domain consisted of a variety of sociodemographic indicators, including but not limited to religion, education, and literacy level. For the DBT-N diary card, we used a series of images depicting emotional states, along a modified Likert scale using a glass with varying levels of water to indicate level of emotional intensity; a similar version of this pictorial scale had previously been validated in Nepal to assess emotional distress among children (Kohrt et al., 2011). To account for clients’ religious backgrounds, we used religious cosmology to highlight interpersonal advantages and disadvantages of positive and negative emotions. For example, we described the unproductive and unrestrained communication of negative emotions to others as a means of harming the karma of both oneself and another.

Metaphors, Imagery, and Symbolism

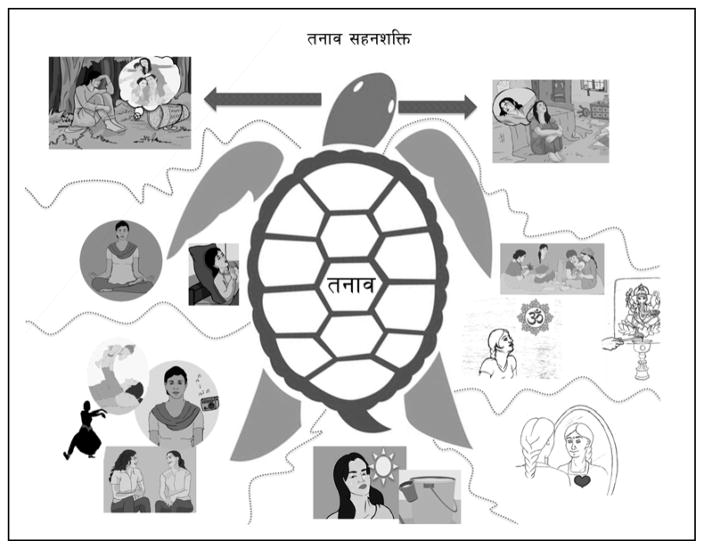

When modifying specific distress tolerance skills during Group Activity 4, we asked workshop members to develop alternatives to text-based acronyms for illiterate or low-literacy patients. One group used the tortoise (kachuwa) and hare metaphor to illustrate the need and utility of tolerating distress. In this allegory, a tortoise bearing the weight (“stress”; Nepali tanaab) of a heavy shell outpaces his opponent by “not acting hastily” and skillfully managing his load. This story described the utility of distress tolerance skills by illustrating the short- and long-term consequences of impulsive action (Figure 2). Others also brainstormed culturally consonant equivalents for remaining skills (e.g., lighting incense, drinking lassi (sweet yogurt drinks often blended with fruit), or adding aromatic masala (mixed spices) to a dish as a self-soothing mechanism). These adaptations were incorporated into the DBT-N manual, with accompanying pictorial aids.

Figure 2.

Nepali version of crisis survival skills: ‘the power to endure stress’ (tanaab sahanshakti). Clockwise, beginning from top right: comparisons, contributing, self- encouragement, sensations, activities, relaxation, and pleasant memories. See Linehan (1993b) for a complete description of distress tolerance skills in DBT.

Skills Training Content

In the case conceptualization exercise, participants unanimously prioritized use of mindfulness skills with clients, partly on account of their belief that focused awareness or “meditation” (both formal and informal) are embedded in common Nepali religious practices and traditions (e.g., Nepali dyan garne, or “giving attention”). Participants also prioritized distress tolerance skills, due to perceptions that they would be readily understood and implemented by low-literacy women. All workshop members were reluctant to incorporate directed assertiveness training into sessions, due to their potential to create long-term physical and emotional harm for rural women raised in a conservative, patriarchal milieu. There was a concern that many of the assertiveness activities would endanger women because of violent responses from their husbands or in-laws. Female assertiveness has also been shown to violate Nepali concepts of laaj (shyness, shame, or self-effacement) for women and is considered disrespectful (Kohrt & Harper, 2008; Shweder, 1999).

In response to these findings, we incorporated lengthier periods of mindfulness and distress tolerance training into the original manual. We also emphasized aspects of self-care and attention to personal and interpersonal needs in a manner that did not risk physical safety. We also tailored skills to known available resources in rural Nepal. For example, a mindful eating exercise using apples was added, since the Jumla district where the pilot trial was conducted is the country’s major exporter of the fruit.

Salient Life Stressors

Throughout the workshop, we asked participants to identify worry thoughts and daily stressors common among self-destructive women. These included financial strain, substance abuse by family members, and restricted opportunities for social networking and engagement in pleasurable social interactions for women in the community. Two groups also raised concerns about reducing treatment-interfering behaviors (e.g., financial or familial constraints to remaining in therapy) in the absence of broader sociocultural change.

In the manual, we therefore included role-plays demonstrating aspects of DBT skills that were tailored to the lay concerns identified above. A group brainstorming of potential microfinance initiatives and linkages to support groups was also included in Session 9.

Nepali Ethnopsychology

During the “Successes & Challenges” group exercise, participants identified ongoing difficulties using traditional cognitive behavioral methods (e.g., identifying links between cognitions and emotions or use of cognitive restructuring and similar change-oriented strategies) with low-literacy clients. (See Tol and colleagues’ 2005 review for further discussion of barriers to traditional psychotherapy methods in Nepal.)

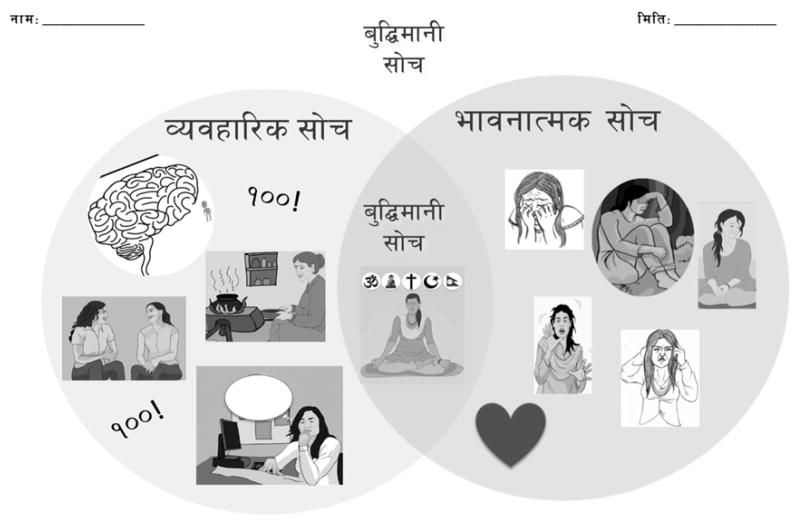

In response, we designed skills embedded in Nepali ethnopsychological models so as to appeal to lay clientele. Wise mind was conceptualized as a synthesis of dimaag (brain-mind) and man2 (heart-mind; see Figure 3). Because of lay concerns that intense, prolonged man problems can lead to dimaag dysfunction and eventual loss of social status, we defined radical acceptance as a means of coping with intense man distress to prevent ultimate loss of valuable social currency.

Figure 3.

DBT-N Wise Mind Handout. The left portion of the handout refers to behavioral thoughts (byabahaarik soch), the domain of the brain-mind (dimaag), with associated images. The right side represents emotional thoughts (bhabanaatmak soch), the domain of the heart-mind (man). The overlapping portion represents wise mind (buddhi mani soch).

Engagement in Therapy

In one small group exercise, we had participants outline notable successes and challenges encountered during past or present interactions with self-destructive clients. All groups considered group components infeasible due to urban-related migration, and preferred one-on-one (1:1) treatment. This perspective was echoed again during the case conceptualization exercise, where 1:1 skills training was prioritized.

In the manual, we consequently developed a rough prototype for individual skills delivery, while preserving the group delivery option if it proved feasible during the treatment pilot.

Study 3: Treatment Pilot Findings and Adaptations to DBT-N Manual

The average age of the 10 participants was 30.8 years (SD = 8.33). Eighty percent of women were fully illiterate. Two (20%) had obtained their School Leaving Certificate (SLC), a secondary school examination in Nepal. The group was equally divided among higher (20% and 30% Bahun and Chhetri, respectively) and lower (50% Dalit/Nepali) castes. Each woman attended an average of 7.9 sessions, with a range of 3 to 10 sessions. One woman dropped out of treatment due to family concerns regarding stigma.

Table 3 provides an overview of treatment structure and flow over the 11-week period. We incorporated ad hoc changes to the DBT-N protocol on a weekly or biweekly basis, depending on issues, sensitivities, or requests that arose in preceding sessions (see Table 4 for a list of Study 3 adaptations).

Table 3.

Outline for DBT-N Treatment Schedule Piloted in Rural Northwest Nepal

| Time | Topics Covered |

|---|---|

| Orientation & Pretreatment | Diary card |

| Contact Information | |

| Treatment Schedule | |

| Group Guidelines | |

| Session Two | Mindfulness* |

| “What” skills: Observe, describe, participate | |

| Chain Analysis | |

| Establish Treatment Targets | |

| Session Three | Mindfulness* |

| Wise mind | |

| “How” skills: One-at-a-time, Nonjudgmentally, Effectively | |

| Chain Analysis | |

| Session Four | Distress Tolerance* |

| DISTRACTS Skills | |

| Self-Soothe Skills | |

| Chain Analysis | |

| Session Five | Distress Tolerance* |

| Radical Acceptance | |

| Chain Analysis | |

| Session Six | Radical Acceptance |

| Self-validation | |

| Step 1: Awareness of Emotion | |

| Step 2: Normalizing of Emotion | |

| Chain Analysis | |

| Session Seven | Self-validation |

| Step 3: Self-forgiveness | |

| Step 4: Self-encouragement | |

| Emotion Regulation | |

| Model for Describing Emotions | |

| Chain Analysis | |

| Session Eight | Emotion Regulation* |

| Mindfulness of Positive Emotion | |

| Reducing Vulnerabilities | |

| Nepali Pleasant Activities | |

| Opposite Action | |

| Chain Analysis | |

| Session Nine | Interpersonal Effectiveness* |

| Relationship Effectiveness | |

| Group Adaptation of Objectives Effectiveness Skills | |

| Safety Plan Development | |

| Chain Analysis | |

| Session Ten | Interpersonal Effectiveness* |

| Objectives Effectiveness Skills | |

| Program Recap & Review | |

| Closing |

Table 4.

Additional DBT-N Manual Modifications During Study 3 Pilot Stage in Rural Nepal

| Suicide and Self-Harm Related Factors | Application to DBT-N Protocol |

|---|---|

| Sociodemographics |

|

| Culturally consonant metaphors, imagery, and symbolism |

|

| Skills training content |

|

| Therapy engagement |

|

| Vulnerability factors |

|

Sociodemographics

Additional, unanticipated barriers arose throughout the program. These included difficulties associating pictorial aids with skills or treatment targets, inabilities to grasp simplified yet abstract psychological concepts, and problems in diary card completion.

Thus, we continued to condense and simplify module-specific skills. For example, Objectives Effectiveness was reduced to a six-step process using culturally relevant pictorial aids. Pictures for each step were included in the accompanying handout. When possible, literate family members were also included in the diary card orientation and instruction process, in order to encourage its completion.

Metaphors, Imagery, and Symbolism

All women were commercial agriculturalists, and identified with skills presented from an agrarian perspective. All women also subscribed to Hinduism, and had limited familiarity with Buddhist concepts. This was in direct contrast to Study 2 participants, who engaged in both Buddhist and Hindu religious worship.

We therefore embedded skills in applicable metaphors, allegories, and symbols to encourage uptake and relevance. For example, self-validation skills were taught using a step-wise process aligned with a common Hindu allegory.3 We also incorporated culturally consonant imagery. For example, compassion meditation was presented using Hindu imagery, which involved cool, yellow light emanating from Shiva’s heart. Farming-specific metaphors (e.g., planting seeds for adaptive and maladaptive emotions, crop harvesting as a metaphor for long-term consequences) were also included.

Skills Training Content

As expected given workshop findings, clients struggled to identify cognitive-affective connections in behavioral chain analysis, and instead emphasized somatic concerns. Women reported difficulties practicing self-validation, due to recurrent feelings of shame and guilt resulting from prolonged domestic conflict.

In response, we incorporated abdominal discomfort, redness of face, and other common, distress-related somatic complaints into weekly chain analyses. Due to continued difficulties with shame and guilt, we added skills for self-forgiveness into the self-validation module. These skills were grounded in local explanatory models, and included heart-mind mapping4 to encourage uptake. Ongoing tailoring of skills to daily resources and realities also occurred (e.g., using a mindful weeding exercise during harvest season, and replacing ice with a cold morning bath to reduce high emotional arousal in the absence of water-freezing technology).

Therapy Engagement

We sought to promote intrinsic motivation to participate in DBT-N through use of nonfinancial incentives. For instance, we distributed low-cost, metal-plated bangles to women after each session. This incentive served as a visual cue of progress in the program.

In line with standard DBT, we also chose to eliminate any direct discussion of suicide and self-harm within group. Rather, we limited group skills training to discussion of suicidal proxy terms only (e.g., feeling “overwhelmed” or “out-of-control”), in order to minimize negative reinforcement and emotional arousal that may result from within-group discussion of suicide-related problems.

Daily mobile phone network interruptions also precluded any possibility of regular phone coaching, which led to omission of this treatment component in the manual.

Vulnerability Factors

Women made frequent references to challenging and unresolved conflicts with family members. As expected given Study 2 findings, traditional assertiveness strategies were also deemed untenable because of safety concerns. In response, we extended interpersonal effectiveness skills review. Protracted discussion and practice of modified assertion strategies (e.g., inclusion of a family mediator or close friend into the request-making process, pronounced validation of others prior to saying no) was included.

Case Study

The following case study provides an illustration of how DBT-N was implemented for an illiterate, rural Nepali woman. The case represents an amalgamation of different patients and narratives in order to preserve anonymity.

Pretreatment and Orientation

Sangeeta is an illiterate, 19-year-old housewife from a low-caste Hindu group known as Dalit. In Nepal, Dalit groups are historically referred to as “untouchables,” and experience significantly greater levels of depression and anxiety compared to higher caste groups (e.g., Kohrt et al., 2012. Sangeeta was referred to our program by her parents, who were concerned about her alternating cycling between angry outbursts and extreme self-isolation behaviors. At 14, she quit school after she was married to a small business owner, who soon after fell in love with an employee and began an extramarital affair. Sangeeta reported regular emotional, psychological, and physical abuse by her partner, and claims her in-laws, with whom she lives, condones his behavior on account of her insubordination at home. At the ages of 16 and 17, she attempted suicide by ingesting a common brand of rat poison, and was taken to the emergency room where she received one round of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), which she reported produced no significant clinical change. Sangeeta revealed problems of sadness, shame, and anger in her man (heart-mind), and reported that dimaag (brain-mind) problems were preventing her from controlling her anger and concentrating on important tasks at home. For the past 14 months, she had not derived any pleasure from activities she had once enjoyed. She had frequent thoughts of killing herself, which were often accompanied by intermittent plans. At the time of referral, she met Nepali criteria for emotion dysregulation, depression, anxiety and posttraumatic stress disorder.

When Sangeeta entered our program, she still lived with her husband and in-laws. They were concerned her participation in a treatment addressing suicidality would publicize her past attempts and bring needless shame to her family. We oriented Sangeeta and her family to DBT-N by explaining that the program provided universal skills for managing emotional problems that could benefit both healthy and mentally ill clients. Sangeeta then identified two treatment targets she wanted to work on while in the program: managing the intense and confusing emotions in her man and developing a healthier relationship with her husband. Both she and her family provided consent for her participation.

Sessions 1–3: Mindfulness and Chain Analysis

In the first three sessions of DBT-N, Sangeeta learned to practice nonjudgmental awareness of her present emotional, somatic, and cognitive state through mindfulness (sachetansilata) “what” (describing, observing, and participating) and “how” (one-mindfully, nonjudgmentally, and effectively) skills. Because of the central role Hindu prayer and traditions played in her and other group members’ daily lives, in-session mindfulness practice included rehearsing “what” and “how” skills by making malas (religious garlands made with flowers, needles, and thread) and practicing observing and describing through a guided visualization of Lord Vishnu, the Hindu god of balance. Since Sangeeta believed many of her problems were due to her prayers not reaching God, we discussed focusing on praying “one-mindfully” to address this concern. Mindfulness was described as a means of reaching wise mind (buddhi mani soch; see Figure 3), which would help her balance her emotions in her man with social duties and responsibilities in her dimaag.

At the end of Session 3, we introduced behavioral chain analysis to help Sangeeta identify, in detail, how a sequence of events (emotions, somatic sensations, and cognitions) could lead up to and follow a public behavior she regarded as problematic and ineffective. She described beating her son earlier in the week, and feeling dizzy, nauseous, and anxious (“words played for hours in my heart-mind”) for hours afterwards. In this instance, practicing wise-mind meant observing and describing her frustration with her son or “taking a five minute break” before acting if she noticed a strong urge to beat him.

At the end of every session, we gave Sangeeta and other group members a diary card in order to track their emotions (joy, sadness, shame, anger, worry, and fear), urges (suicidal and self-harming) and behaviors (self-harming incidents) between sessions. To address her illiteracy, photos of Nepali women in the corresponding emotional states were included in the handouts. Sangeeta recorded her emotions and urges through a pictorial scale ranging from 0–4, where “0” was illustrated by an empty cup of water (lack of emotion or urge) and “4” with an overflowing cup (an intense emotion or urge). After the first session, Sangeeta had difficulties remembering which photograph corresponded to each emotion. We oriented her literate cousin to the diary card following the session, who helped her complete them for the remainder of the program.

Sessions 4–5: Distress Tolerance

Strategies for reducing intense emotions in Sangeeta’s man were framed using distress tolerance skills. We used the tortoise and hare handout (Figure 2) described earlier to help justify her need to tolerate her overwhelming emotions, and provided in-session opportunities for practicing select skills (prayer, making comparisons, and experiencing alternate, intense sensations). Sangeeta said that taking frigid morning baths was useful in diverting intense feelings of anxiety she often felt upon waking up. We also taught self-soothe skills, when being gentle and kind to herself was an available option. She expressed initial resistance to practicing self-soothing skills, which we later discovered was due to feelings of embarrassment because she could not afford the “luxurious” soothing mechanisms her wealthier, higher-caste group members invested in. We brainstormed pleasing yet low-cost alternatives for her that included lighting scented incense or flavoring routine lunch recipes with new spices in her pantry.

Of all the skills in this module, Sangeeta had the most difficulty distinguishing radical acceptance (described as leaving things up to God by letting go of fighting reality from deep within us) from a karmic belief that she was destined to suffer because of her past suicide attempts. Other group members experienced similar difficulties. Thus, in Week 5, we spent the majority of the second-half of the session demonstrating how accepting fate could also mean actively searching for ways to change or challenge her current situation. We also emphasized that radical acceptance includes accepting valid emotions in one’s man, which, by reducing high emotional arousal, could help prevent loss of ijjat (social status) by encouraging healthy dimaag functioning.

Sessions 6–7: Self-Validation

Due, in part, to an abusive domestic environment and cultural expectations of prioritizing others’ needs over her own, Sangeeta had difficulties practicing distress tolerance skills due to feelings of blameworthiness, worthlessness, and shame. In Sessions 6 and 7, she learned self-validation skills using the Hindu Clay Pot metaphor to boost her confidence and encourage her to take herself and emotions seriously. We broke these skills into steps to support her learning. First, she learned to be mindful of her current emotion and normalize valid components of it. We then taught her how to forgive herself for past mistakes or self-judgments using a man mapping exercise where she identified and let go of negative man feelings associated with an event she regretted or had self-judgments about. We also reminded her that self-forgiveness is a noble trait in Hinduism, and is described in religious texts as a means to wisdom and liberation in following lives. Lastly, she was taught self-encouragement skills to help take herself seriously and identify positive aspects of difficult situations.

In Session 7, Sangeeta’s diary card indicated a suicidal urge of “4” and a self-harm incidence during the prior week. In line with standard DBT, however, group guidelines prevented us from directly targeting these behaviors in-session. Group co-leaders presented the option of individual sessions, but she declined because she found her 3-hour weekly commute to sessions burdensome and preferred us not conduct sessions at her home due to privacy concerns. She agreed, however, to meet for an additional hour following our session in order to conduct an individualized chain and solution analysis.

Sessions 7–8: Emotion Regulation

Within these two sessions on emotion regulation, Sangeeta learned the following skills: (a) identifying and labeling emotions, (b) mindfulness of one’s current emotion, (c) reducing emotional vulnerability through self-care, (d) building positive experiences, and (e) acting opposite to ineffective behavioral urges. We used a “Tree of Life” analogy to build the standard model for experiencing and describing emotions: prompting events were equivalent to soil, interpretations to roots, the emotional experience to a tree trunk, emotional expressions to flowers, and consequences to fruits. Because Sangeeta valued an understanding of her identity in the context of others, we taught her that ineffective and unregulated emotions in her were like pesticides that seeped deep into soil and damaged both her and others’ seeds. By practicing emotion regulation skills, she could prevent this process from occurring. Sangeeta reported the greatest benefit from use of opposite action skills, which included being polite towards her husband when angry with him, in order to maintain (and ultimately improve) the relationship.

Sessions 9–10: Interpersonal Effectiveness

As mentioned earlier, one of Sangeeta’s primary treatment targets was improving her relationship with an abusive husband. In these last sessions, we taught her to balance her desire to improve her relationship with a desire to fulfill important relationship objectives like paying their son’s tuition on time. Sangeeta said she already practiced relationship effectiveness skills (acting interesting, being gentle, and validating), though role-play exercises indicated that she had difficulty validating the valid. Due to fear of further domestic abuse, she and other group members initially resisted use of step-wise objectives effectiveness skills: (a) waiting for the right time, (b) looking confident, (c) validating the other person, (d) describing the situation and your feelings, (e) asking for what you want, and (f) negotiating. This resistance persisted after conducting a pros and cons of relationship assertiveness vs. passivity. In Session 9, we brainstormed safe alternatives to these assertiveness skills as a group. For Sangeeta, this meant using an intermediary (her father-in-law, with whom she had a moderately stable relationship) to get her marital objectives met. She practiced the five skills with her father-in-law, who was successful in obtaining her son’s tuition deposit from her husband.

Discussion

This paper describes the manualized, cross-cultural adaptation of traditional DBT to a resource-strained rural Nepali setting, using a phasic, iterative, and collaborative process approach. In Study 1, interviews with key stakeholders in the Nepali mental health community were identified to explore risk factors and perceptions of suicide and nonsuicidal self-injury, as well as identify salient domains for cross-cultural adaptation. In Study 2, an initial adaptation workshop was conducted with Nepali mental health providers to further inform the development of a DBT-N manual. In Study 3, a process analysis of an exploratory DBT-N pilot with 10 suicidal and self-harming women of reproductive age was conduced, in order to continue the process of manual refinement. DBT-N was delivered to 10 women in the Jumla district of Nepal, most of whom were illiterate. One lay counselor trained in Study 2 co-facilitated the program. Participants attended an average of 7.8 group sessions, which were characterized by a series of preliminary successes and challenges.

Specific modifications to encourage comprehensibility were well-received by illiterate women in the group. These examples include diary card simplification, stepwise presentation of skills, and use of pictorial aids. Mindfulness skills were also met with a high level of enthusiasm by clients. Despite this enthusiasm, however, clients struggled to grasp the concept of wise mind (buddhi mani soch). This struggle persisted in light of ethnopsychological modification and extended experiential training. This finding was surprising to members of the study team, as there is a rich body of religious and secular history supporting the idea of balance and equanimity in South Asia (e.g., Mukherjee & Wahile, 2006). Our failure to sufficiently modify “wise mind” to a local, lay conceptualization of balance and interdependence may contribute to this issue. Research examining the utility of mindfulness-based interventions with Asian-American populations have also identified this potential barrier (Hall, Hong, Zane, & Meyer, 2011). Another salient threat to retention is community and internalized stigma, whereby mentally ill clients are perceived as irreparably weak or incurable (Kohrt & Harper, 2008). Interventions are thus appropriate for “failed” clients, leading to stigma against the client, and possibly the treatment itself. This mirrors aspects of Nepali ethnopsychology, whereby brain-mind problems (such as suicide) lead to socially dysregulated behavior and loss of social status (ijjat) (Kohrt et al., 2012). However, stigma surrounding DBT-N did not appear to significantly impact treatment adherence. It is possible that engagement-targeting adaptations were a sufficient counter to this barrier. Alternatively, because all clients were either self-referred or referred by immediate family members, it is possible that the pilot group was self-selecting and thus inherently more motivated to attend sessions.

An unanswered question is the level of adaptation that is required for optimal outcomes. According to one meta-analysis by Gonzales and colleagues (2014), culturally adapted interventions demonstrate moderate effect sizes, with an average effect size of d = 0.45 compared to nonadapted control groups. However, a small but growing body of evidence suggests that cultural tailoring may have neutral or even potentially iatrogenic effects (e.g., Huey, 2013; Kliewer et al., 2011). Even in light of this evidence, however, a standardized definition of cultural adaptation does not exist. Studies comparing adapted vs. nonadapted variants often fail to explicitly define and justify domains for adaptation, and may sometimes conflate “adaptation” with superficial logistical modifications (e.g., treatment location or session duration) that would also be natural and obvious targets in nonadapted variations. Further, these comparison studies are few in number and heterogeneous in their clinical targets.

In this study, we explicitly define “adaptation” as a host of factors that move beyond logistical modifications in order to delineate a more meaningful level of intertreatment difference for future comparison studies in Nepal. Similarly, Resnicow and colleagues (2000) have identified a distinction between surface structure and deep structure adaptations. Surface structure adaptations, like the ones outlined above, incorporate changes to original interventions that address easily observable (“superficial”) elements of a particular group’s culture such as language, music, and specific ethnocultural traditions. Deep structure adaptations, however, may include modifications of the core components of the original treatment. Evidence of the effectiveness of these deeper, structural-level changes are mixed. For standard DBT, specifically, the boundaries of deep and superficial structure are murky. Few mediation studies have been conducted to identify core, active ingredients or change processes worthy of conservation (Neacsiu et al., 2014). There is also considerable debate regarding the potential for briefer and more parsimonious alternatives to the comprehensive DBT model. At present, there are a limited number of published component analyses of DBT, with one recent trial (Linehan et al., 2015) supporting the stand-alone efficacy of skills training combined with structured case management. In the absence of further evidence, we chose to prioritize comprehensibility and accessibility in designing the intervention, collaborating with therapists and clients to eliminate or modify impractical or infeasible elements.

Limitations and Implications for Future Research

This study had a number of limitations. It was conducted with one specific subcultural group in rural Nepal, defined by geographic location, religious orientation, gender, and occupation. The generalizability of DBT-N across a number of distinct subpopulations (e.g., school children or adolescents with high rates of self-harm, men and women in peri-urban or urban areas, proponents of Buddhism or a syncretic blend of Buddhist and Hindu traditions, among others) is thus limited. Further, the current results are limited to formative, qualitative work. Structured and randomized trials examining the effectiveness of DBT-N against a variety of control groups are necessary.

Despite these limitations, the current study sheds new light on four future directions in this line of adaptation work. First, models for how emotion dysregulation is generated in suicidal and self-harming individuals should be constructed, along with a detailed and systematic description of co-occurring symptoms and comorbidities. For the local Jumla population, for example, the mechanism through which specific psychological or physiological complaints are generated for self-destructive women should be identified. Understanding the mechanisms that maintain disorder symptoms are crucial for development of simple, targeted, and responsible treatments (Barlow, Allen, & Choate, 2004). In Nepal, a working ethnopsychological framework that broadly explains the development of common and more severe mental illness has been proposed (Kohrt & Harper, 2008). However, this model does not specifically address more proximal and local causes of emotion dysregulation. This can be accomplished through further exploratory research with Nepali participants.

Second, though DBT-N was developed in order to target reduction in suicidal and self-injurious behaviors, future studies should explore its transdiagnostic potential, for example its effectiveness across common mental disorders (cf., Murray et al., 2014), including BPD. To this end, use of dismantling study designs is also warranted, in order to identify salient mediators and moderators.

Efforts should also be taken to improve sustainable training and supervision. Because effective delivery of DBT requires multilevel mastery of key treatment principles, training in the modified Nepali version should be conducted on a regular or semiregular basis for lay counselors to gain sufficient mastery over key techniques. Trainings should also include direct assistance in development of a DBT-specific consultation team to promote therapist treatment adherence and efficacy. One option would be to conduct an initial, protracted training (e.g., 10 to 12 days, similar in length to other psychological treatment trainings conducted in Nepal), followed by repeated “booster sessions” to target specialized learning components and issues encountered by therapists who have begun utilizing the skills with clients. Given the complexity and diversity of skills needed, DBT-N would be especially amenable to “apprenticeship models,” which have been advocated for in global mental health (Murray et al., 2011). Ideally, future studies would incorporate a combination of these elements.

Further, this study suggests that psychological interventions are likely to be insufficient unless broader sociocultural concerns are simultaneously addressed (e.g., poverty and domestic violence). DBT-N should continue to incorporate novel interpersonal treatment elements and referrals for issues including domestic violence, alcoholism, and women’s access to reliable financial and educational opportunities. In other settings, programs combining social work case management with group therapy (e.g., Miranda, Azocar, Organista, Dwyer, & Areane, 2014) result in better outcomes on psychological indicators, lending support to this suggestion. In addition, public health programs limiting or restricting access to suicidal means have also demonstrated success in South Asia (WHO, 2014).

In the context of a largely collectivist culture like Nepal, family-level interventions for self-harming clients and their family members may be especially useful in promoting and sustaining further mental health improvements. In other settings, DBT-informed interventions at the family level are supported by promising empirical support (e.g., Hoffman et al., 2005).

Conclusion

With increasing global diversity and interest in ensuring the cultural congruence of evidence-based interventions, there is a need to use systematic, data-driven approaches to culturally adapt therapies developed in high-income settings for low- and middle-income contexts. DBT, an empirically supported treatment that addresses suicidal behaviors, is an integrative and pliable third-wave cognitive behavioral therapy with roots in Eastern philosophical traditions. Given the high rate of self-destructive behaviors among women and the theorized cultural acceptability of central DBT tenets in Nepal, we chose to adapt DBT for ethnic Nepalis in a naturalized setting, using a dynamic adaptation process. We identified salient challenges in client uptake of DBT-N skills and proposed four suggestions for similar interventions deployed in other LMIC contexts. Future work exploring DBT-N’s effectiveness, transdiagnostic potential, underlying ethnopsychological mechanisms of disorder, and relation to essential public health services is needed to expand its role in Nepal.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from Duke Global Health Institute and Duke University Center for International Studies (to MKR). The senior author (BAK) receives salary support from the National Institute of Mental Health (K01MH104310).

The authors are grateful to the research and clinical staff at TPO-Nepal for their ongoing support of this project. We thank Nagendra Luitel, Prakash Acharya, and Sauharda Rai for their valuable feedback throughout the pilot. We are especially grateful to Nanda Raj Acharya for his clinical support delivering DBT-N. Thanks to Bonnie Kaiser, Josh Rivenbark, and Cori Tergesen for reviewing the manuscript. Special thanks to Alex Morgan for designing a majority of the artwork accompanying the manual.

Footnotes

Ethnopsychology is defined as the study of cultural or “folk” models of psychological subjectivity (Kohrt & Harper, 2008), and is considered a powerful means of uncovering a culture’s own understanding and experience of the self, emotions, physical body, and connections to the social world.

In Nepal, the man is locus of memory and emotions, and is the source of one’s irreducible originality (Kohrt & Harper, 2008). It includes the domains of individual psychological affect, concentration, motivation, intentionality, and subjective opinion. Common, normative levels of emotions are localized to the heart-mind. This conceptualization of man is similar to those found in other South Asian cultures (e.g., India and Bangladesh; Fenton & Sadiq-Sangster, 1996).

In this story, a Nepali water-bearer carries two pots, one of which contains a large crack. This allowed it to only deliver of fraction of the other pot's water to its master. One day, the broken pot spoke to the water-bearer, expressing shame and self-blame as a result of inability to mend the fissure. Her master had her notice a row of marigolds flourishing directly beneath the leaking point, and proclaimed: "For two years, I have been able to pick these beautiful flowers to decorate my table. Without you being just the way you are, he would not have this beauty to grace his house.” We used this allegory to demonstrate the utility of self-forgiveness, self-awareness, and self-encouragement in the context of validation.

Heart-mind mapping is a technique previously developed for use with children to promote identification and engagement in personally tailored coping strategies (Karki, Kohrt, & Jordans, 2009).

References

- Adhikari RP, Kohrt BA, Luitel NP, Upadhaya N, Gurung D, Jordans MJ. Protective and risk factors of psychosocial wellbeing related to the reintegration of former child soldiers in Nepal. Intervention. 2014;12(3):367–378. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Allen LB, Choate ML. Toward a unified treatment for emotional disorders. Behavior Therapy. 2004;35(2):205–230. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M, Castro FG. A heuristic framework for the cultural adaptation of interventions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2006;13(4):311–316. [Google Scholar]

- Baumann AA, Domenech Rodríguez MM, Amador NG, Forgatch MS, Parra-Cardona JR. Parent Management Training–Oregon Model (PMTO™) in Mexico City: Integrating cultural adaptation activities in an implementation model. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2014;21(1):32–47. doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benish SG, Quintana S, Wampold BE. Culturally adapted psychotherapy and the legitimacy of myth: A direct-comparison meta-analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2011;58(3):279. doi: 10.1037/a0023626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal G, Jiménez-Chafey MI, Domenech Rodríguez MM. Cultural adaptation of treatments: A resource for considering culture in evidence-based practice. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2009;40(4):361. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton P, Bass J, Neugebauer R, Verdeli H, Clougherty KF, Wickramaratne P, … Weissman M. Group interpersonal psychotherapy for depression in rural Uganda: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289(23):3117–3124. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton P, Surkan PJ, Gray AE, Desmousseaux M. The mental health and psychosocial effects of organized violence: A qualitative study in northern Haiti. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2012;49(3–4):590–612. doi: 10.1177/1363461511433945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro FG, Barrera M, Jr, Steiker LKH. Issues and challenges in the design of culturally adapted evidence-based interventions. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2010;6:213–239. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-033109-132032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhary N, Anand A, Dimidjian S, Shinde S, Weobong B, Balaji M, … Araya R. The Healthy Activity Program lay counsellor delivered treatment for severe depression in India: systematic development and randomised evaluation. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2015;208:381–388. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.161075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domenech Rodriguez M, Wieling E. Developing culturally appropriate, evidence-based treatments for interventions with ethnic minority populations. In: Rastogin M, Weiling E, editors. Voices of color: First person accounts of ethnic minority therapists. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2004. pp. 313–333. [Google Scholar]

- Fenton S, Sadiq-Sangster A. Culture, relativism and the expression of mental distress: South Asian women in Britain. Sociology of Health & Illness. 1996;18(1):66–85. [Google Scholar]

- Fruzzetti AE, Erikson KM. DBT treatment manual for women victims of domestic violence. Reno: University of Nevada; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Lau A, Murry VM, Pina A, Barrera M., Jr . Developmental Psychopathology. 3. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2014. Culturally adapted preventive interventions for children and youth. [Google Scholar]

- Hagaman AK, Maharjan U, Kohrt BA. Suicide surveillance and health systems in Nepal: a qualitative and social network analysis. International Journal of Mental Health Systems. 2016;10(1):1–19. doi: 10.1186/s13033-016-0073-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall GC, Hong JJ, Zane NW, Meyer OL. Culturally competent treatments for Asian Americans: The relevance of mindfulness and acceptance-based psychotherapies. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2011;18(3):215–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2011.01253.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Villatte M, Levin M, Hildebrandt M. Open, aware, and active: Contextual approaches as an emerging trend in the behavioral and cognitive therapies. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2011;7:141–168. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032210-104449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton DE, Chhean D, Pich V, Safren SA, Hofmann SG, Pollack MH. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavior therapy for Cambodian refugees with treatment-resistant PTSD and panic attacks: A crossover design. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2005;18(6):617–629. doi: 10.1002/jts.20070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman PD, Fruzzetti AE, Buteau E, Neiditch ER, Penney D, Bruce ML, … Struening E. Family connections: A program for relatives of persons with borderline personality disorder. Family Process. 2005;44(2):217–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2005.00055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huey SJ. A meta-analysis of culturally tailored versus generic psychotherapies. Presented at at the 121st annual meeting of the American Psychological Association; Honolulu, HI. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang WC. The psychotherapy adaptation and modification framework: Application to Asian Americans. American Psychologist. 2006;61(7):702. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.7.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iverson KM, Shenk C, Fruzzetti AE. Dialectical behavior therapy for women victims of domestic abuse: a pilot study. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2009;40(3):242. [Google Scholar]

- Jordans MJD, Luitel NP, Pokhrel P, Patel V. Development and pilot testing of a mental healthcare plan in Nepal. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2016;208(s56):s21–s28. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.153718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karki R, Kohrt BA, Jordans MJ. Child led indicators: Pilot testing a child participation tool for psychosocial support programmes for former child soldiers in Nepal. Intervention. 2009;7(2):92–109. [Google Scholar]

- Kliewer W, Lepore SJ, Farrell AD, Allison KW, Meyer AL, Sullivan TN, Greene AY. A school-based expressive writing intervention for at-risk urban adolescents’ aggressive behavior and emotional lability. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2011;40(5):693–705. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.597092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohrt BA, Harper I. Navigating diagnoses: Understanding mind–body relations, mental health, and stigma in Nepal. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry. 2008;32(4):462–491. doi: 10.1007/s11013-008-9110-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohrt BA, Hruschka DJ, Worthman CM, Kunz RD, Baldwin JL, Upadhaya N, … Jordans MJ. Political violence and mental health in Nepal: prospective study. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;201(4):268–275. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.096222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohrt BA, Jordans MJ, Tol WA, Luitel NP, Maharjan SM, Upadhaya N. Validation of cross-cultural child mental health and psychosocial research instruments: adapting the Depression Self-Rating Scale and Child PTSD Symptom Scale in Nepal. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11(1):127. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-11-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohrt BA, Kunz RD, Koirala NR, Sharma VD, Nepal MK. Validation of a Nepali version of the Beck Depression Inventory. Nepalese Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;2(4):123–130. [Google Scholar]

- Kohrt BA, Maharjan SM, Timsina D, Griffith JL. Applying Nepali ethnopsychology to psychotherapy for the treatment of mental illness and prevention of suicide among Bhutanese refugees. Annals of Anthropological Practice. 2012;36(1):88–112. [Google Scholar]

- Kohrt BA, Worthman CM. Gender and anxiety in Nepal: The role of social support, stressful life events, and structural violence. CNS Neuroscience and Therapeutics. 2009;15(3):237–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2009.00096.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumpfer KL, Pinyuchon M, de Melo AT, Whiteside HO. Cultural adaptation process for international dissemination of the Strengthening Families Program. Evaluation & the Health Professions. 2008;31(2):226–239. doi: 10.1177/0163278708315926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau AS. Making the case for selective and directed cultural adaptations of evidence-based treatments: Examples from parent training. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2006;13(4):295–310. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan M. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press; 1993a. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan M. Skills training manual for treating borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press; 1993b. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Korslund KE, Harned MS, Gallop RJ, Lungu A, Neacsiu AD, … Murray-Gregory AM. Dialectical behavior therapy for high suicide risk in individuals with borderline personality disorder: A randomized clinical trial and component analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(5):475–482. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.3039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda J, Azocar F, Organista KC, Dwyer E, Areane P. Treatment of depression among impoverished primary care patients from ethnic minority groups. Psychiatric Services. 2014;54(2):219–225. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee PK, Wahile A. Integrated approaches towards drug development from Ayurveda and other Indian system of medicines. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2006;103(1):25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray LK, Dorsey S, Bolton P, Jordans MJ, Rahman A, Bass J, Verdeli H. Building capacity in mental health interventions in low resource countries: An apprenticeship model for training local providers. International Journal of Mental Health Systems. 2011;5(1):30. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-5-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray LK, Dorsey S, Haroz E, Lee C, Alsiary MM, Haydary A, … Bolton P. A common elements treatment approach for adult mental health problems in low-and middle-income countries. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2014;21(2):111–123. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neacsiu AD, Eberle JW, Kramer R, Wiesmann T, Linehan MM. Dialectical behavior therapy skills for transdiagnostic emotion dysregulation: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Behavior Research and Therapy. 2014;59:40–51. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V. The future of psychiatry in low- and middle-income countries. Psychological Medicine. 2009;39(11):1759–1762. doi: 10.1017/s0033291709005224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Weiss HA, Chowdhary N, Naik S, Pednekar S, Chatterjee S, … Kirkwood BR. Effectiveness of an intervention led by lay health counsellors for depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care in Goa, India (MANAS): A cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376:2086–2095. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61508-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman A, Malik A, Sikander S, Roberts C, Creed F. Cognitive behaviour therapy-based intervention by community health workers for mothers with depression and their infants in rural Pakistan: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9642):902–909. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61400-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnicow K, Soler R, Braithwaite RL, Ahluwalia JS, Butler J. Cultural sensitivity in substance use prevention. Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28(3):271–290. [Google Scholar]

- Shweder RA. Why cultural psychology? Ethos. 1999;27(1):62–73. [Google Scholar]

- Singla DR, Kumbakumba E, Aboud FE. Effects of a parenting intervention to address maternal psychological wellbeing and child development and growth in rural Uganda: a community-based, cluster-randomised trial. The Lancet Global Health. 2015;3(8):e458–e469. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00099-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suvedi BK, Pradhan A, Barnett S, Puri M, Chitrakar SR, Poudel P, … Hulton L. Nepal maternal mortality and morbidity study 2008/2009: Summary of preliminary findings. Kathmandu, Nepal: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tol WA, Jordans MJ, Regmi S, Sharma B. Cultural challenges to psychosocial counselling in Nepal. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2005;42(2):317–333. doi: 10.1177/1363461505052670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Loon A, van Schaik A, Dekker J, Beekman A. Bridging the gap for ethnic minority adult outpatients with depression and anxiety disorders by culturally adapted treatments. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2013;147(3):9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]