Abstract

The theoretical and philosophical underpinnings of a eudaimonic model of well-being are examined and its empirical translation into distinct dimensions of well-being is described. Empirical findings have documented aging declines in eudaimonic well-being, but there is considerable variability within age groups. Among older adults who remain purposefully engaged, health benefits (reduced morbidity, extended longevity) have been documented. Eudaimonic well-being also appears to offer a protective buffer against increased health risk among the educationally disadvantaged. Neural and genetic mechanisms that may underlie eudaimonic influences on health are briefly noted, and interventions designed to promote eudaimonic well-being are sketched. Needed future research directions include addressing problems of unjust societies wherein greed among privileged elites may be a force compromising the eudaimonic well-being of those less privileged. Alternatively, and more positive in focus, is the need to better understand the role of the arts, broadly defined, in promoting eudaimonic well-being across all segments of society.

Keywords: eudaimonic well-being, aging, inequality, neural and genetic mechanisms, interventions, unjust societies, the arts

1 Introduction

This article puts forth a eudaimonic model of well-being focused on realization of human potential. The theoretical and philosophical foundations of the approach are summarized, and its empirical translation is briefly described. Extensive research has grown up around this model of well-being. Broad themes within that literature are highlighted, including recent advances from MIDUS (Midlife in the U.S.), a national longitudinal sample of adults. The health protective influences of eudaimonic well-being are illustrated with two lines of inquiry. The first pertains to the challenges of growing old wherein evidence documents decline in certain aspects of well-being as people age from middle to later adulthood. However, among older individuals who maintain high levels of purposeful life engagement, health benefits have been documented. These include extended length of life, reduced risk of multiple disease outcomes, reduced dysregulation of physiological systems, and greater likelihood of practicing preventive health behaviors. The second domain of health protective effects pertains to research on social inequality. Although low socioeconomic status is known to predict increased risk for poor health outcomes, evidence is mounting that well-being provides a buffer. To illuminate possible mechanisms involved in these salubrious findings, work linking eudaimonia to neuroscience and gene expression involved in inflammatory processes is noted. In addition, interventions designed to promote eudaimonia are briefly summarized. Two directions for future research are considered. One addresses problems of unjust societies, wherein the self-serving behaviors (greed) of privileged elites may compromise the eudaimonic well-being of disadvantaged segments of society. The second direction, more positive in tone, calls for consideration of the role of the arts, broadly defined, in nurturing meaningful, fulfilling, and socially responsible lives – i.e., the essence of eudaimonia.

2 A eudaimonic model of well-being

Looking to the past, literatures from developmental and clinical psychology as well as existential and humanistic psychology (Allport 1961; Bühler 1935; Erikson 1959; Frankl 1959; Jahoda 1958; Jung 1933; Maslow 1968; Neugarten 1973; Rogers 1961) sought to articulate the upside of the human experience. For many years, these perspectives had limited scientific impact due to an absence of credible assessment tools to measure the diverse aspects of flourishing they described. This observation led to work (Ryff 1989) that sought to: (1) identify points of convergence in the above perspectives and (2) use these common themes as a foundation for development of quantitative measurement scales. The scale construction process followed the construct-oriented approach to personality assessment (Jackson 1967; Jackson 1976; Wiggins 1973), which begins with conceptually-based definitions of the dimensions to be operationalized. Self-descriptive items are then generated based on the guiding definitions. In an era of proliferating tools to assess well-being, many emerging from positive psychology, it is worth noting that few have clearly formulated theoretical foundations. In addition, few new tools have been subjected to rigorous empirical scrutiny required to test their reliability, validity, and dimensional structure. The above model of eudaimonic well-being came with a strong conceptual foundation, and its empirical translation was accompanied by extensive psychometric evaluation. These features likely explain why the model has withstood extensive scrutiny over time and has been extensively employed across diverse domains of inquiry (Ryff 2014).

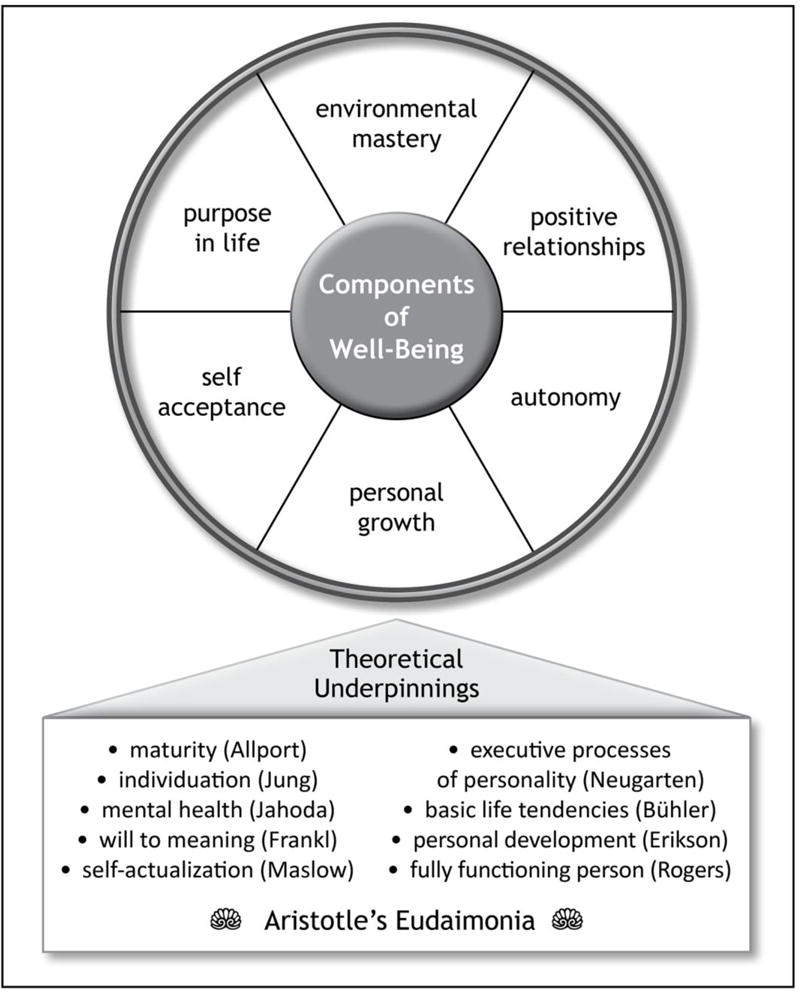

Figure 1 identifies the six key components of the Ryff (1989) model and below them, summarizes theoretical underpinnings. How each dimension of well-being drew on multiple underlying theoretical conceptions in distilling components of optimal human functioning is described below.

Figure 1. CORE DIMENSIONS OF PSYCHOLOGICAL WELL-BEING AND THEIR THEORETICAL FOUNDATIONS.

Reprinted with permission from:

Ryff CD (2016) Eudaimonic well-being and education: Probing the connections. In: Harward DW (ed) Well-being and higher education: A strategy for change and the realization of education’s greater purposes. Bringing Theory to Practice, Washington, DC, pp 37–48

Autonomy

Many efforts to depict key features of positive human functioning emphasize independent, self-determining, and self-regulating qualities of the person. Self-actualizers were described as showing autonomous functioning and resistance to enculturation (Maslow). The fully functioning person was depicted as having an internal locus of evaluation (Rogers), such that one does not look to others for approval, but evaluates oneself by personal standards. Individuation was also described as involving a deliverance from convention (Jung). Life-span theories emphasized the importance of turning inward in later life (Erikson) and gaining a sense of freedom from the norms governing everyday life (Neugarten).

Environmental Mastery

Possessing the ability to choose or create environments suitable to one’s psychic needs was a key characteristic of mental health (Jahoda), which reflected a kind of fit between one’s outer and inner worlds. Life-span theories described the importance of being able to manipulate and control complex environments, particularly in midlife, as well as the capacity to act on and change the surrounding world through mental and physical activities (Erikson, Neugarten). Maturity was defined as being able to extend the self into spheres of endeavor that go beyond the self (Allport). Together, these perspective conveyed that active participation in and efforts to gain mastery of one’s surrounding environment are important elements in positive psychological functioning.

Personal Growth

This aspect of well-being is concerned with self-realization and achieving personal potential. It thus underscores the dynamic aspects of positive functioning that are continually evolving through time. Self-actualization was centrally concerned with personal becoming (Maslow), as was positive mental health (Jahoda). Descriptions of the fully functioning person (Rogers 1961) and what it means to be fully individuated (Jung) also emphasized ideas of realizing one’s true self. Life-span theories, in addition, gave explicit emphasis to confronting new challenges and tasks at different periods of life (Erikson, Bühler, Neugarten).

Positive Relations with Others

The ability to love was deemed a central feature of mental health (Jahoda). Self-actualizers were described as having strong feelings of empathy and affection for all human beings and the capacity for great love, deep friendship, and close identification with others (Maslow). Warm relating to others was seen as a central criterion of maturity (Allport). Adult developmental stage theories (Erikson) emphasized the achievement of close unions with others (intimacy) as well as having a concern for guiding and directing others (generativity). It is worth noting that philosophical accounts of the criterial goods of a well-lived life (Becker 1992) also underscored the primacy of love, empathy, and affection.

Purpose in Life

Having beliefs that give one a sense of purpose and meaning in life was part of positive mental health (Jahoda). The definition of maturity also included having a clear comprehension of one’s purpose, which was important in contributing a sense of directedness and intentionality to life (Allport). Life-span theories depicted changing purposes or goals with different life stages, such as being creative or productive in midlife, and turning to emotional integration in later life (Erikson, Neugarten, Jung). Existential formulations, especially the search for meaning in the face of significant adversity (Frankl), were directly concerned with the challenge of finding/creating meaning amidst suffering.

Self-Acceptance

Having positive self-regard is a central feature of self-actualizers (Maslow), maturity (Allport), optimal functioning (Rogers), and mental health (Jahoda). Lifespan theories also emphasized the importance of acceptance of self, including of one’s past life (Erikson, Neugarten). The process of individuation (Jung) added important refinements to this aspect of well-being – namely, the need to come to terms with the dark side of one’s self (the shadow). This form of self-acceptance is notably richer than standard views of self-esteem because it involves awareness and acceptance of personal strengths as well as weaknesses.

Before moving to scientific findings that have grown up around these dimensions of well-being, it is important to explicate connections to “eudaimonia,” written about by Aristotle in his Nichomachean Ethics (350 B.C., translated by Ross, 1925). His objective was not to formulate the nature of human well-being, but rather to pose an answer to the fundamental question of human existence: namely, how should we live? In reaching for the “highest of all human goods achievable by human action,” Aristotle spoke of happiness, but underscored that it was not some obvious and plain thing like pleasure, wealth, or honor. For him, the highest of all human goods was activity of the soul in accord with virtue. It was in elaborating the highest of all virtues that Aristotle got to the heart of eudaimonia, which he saw a realization of one’s true potential – achieving the best within one’s self. In the present era, Norton’s (1976), Personal Destinies: A Philosophy of Ethical Individualism framed eudiamonism as an ethical doctrine in which each person is obliged to know and live in truth with his daimon, a kind of spirit given to all persons at birth. It is a journey of progressively actualizing an excellence (from the Greek arête) consistent with innate potentialities. Eudaimonia thus embodies the great Greek imperatives of self-truth (know thyself) and self-responsibility (become what you are) (Ryff and Singer 2008).

Reflecting on ideas covered above, one sees parallels in developmental, humanistic, existential, and clinical formulations with Aristotle’s characterization of eudaimonia – the highest good – as self-realization, played out individually, each according to personal dispositions and talents. Interestingly, none of the psychological perspectives on personal development, self-actualization, maturity, individuation, fully functioning, or good mental health, generated 2000+ years after Aristotle, mentioned his work. Nonetheless, the foundational thinking in his Ethics was there implicitly. That is, 20th century enactments of optimal human functioning brought forth new directions in science and practice that were undeniably in the spirit of Aristotle’s eudiamonism.

3 Empirical highlights: Eudaimonia, life challenges and health

Measures of well-being from the above dimensions (Ryff 1989) have been translated to more than 30 languages and have led to 500+ publications. Diverse topics are in this literature (see Ryff 2014), only two of which are of interest here – namely, studies that have explicated the relevance of eudaimonic well-being for human health as well as translational efforts to promote eudaimonia. In the health arena, studies of well-being stands in marked contrast to a longstanding bias toward studying health in terms of disease, disability, dysfunction, and death. The fundamental shift is toward construing health as health (Ryff and Singer 1998), such as the distant WHO (World Health Organization 1948) declaration, which defined health as a “state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” (p.1), or Antonovsky’s (1979;s (1987) formulation of salutogenesis as good health. Relatedly, research on human resilience is also concerned with human capacities to maintain well-being and health in confrontations with significant life challenges (Ryff et al., 2012). Existential and humanistic psychology had, in fact, framed encounters with adversity as catalysts that could fuel deepened experiences of personal growth, self-acceptance, and self-realization. Two prominent life challenges are considered below; the first addresses the losses that accompany human aging and the second examines difficulties that accompany socioeconomic disadvantage.

3.1 Challenges of aging

Early cross-sectional work revealed that older adults had lower levels on personal growth and purpose in life compared to young and midlife adults (Ryff 1989). Subsequent longitudinal evidence from multiple studies, including two national samples, verified that decline in purpose and growth as individuals aged (Springer et al. 2011). However, because high variability was evident among older adults, unique opportunities emerged for investigating links between well-being and health. That is, although the overall age profile showed decrementing levels of purpose and growth, some older adults were decidedly above the average for their age group. This capacity to maintain high levels of well-being was then, in a series of investigations, linked with multiple benefits for health and longevity.

For example, a community-based epidemiological study known as MAP (Rush Memory and Aging Project) showed, after controlling for numerous covariates, that older adults with higher levels of purpose in life at baseline had reduced risk of death six years later (Boyle et al. 2009) as well as reduced risk of Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment (Boyle et al. 2010). More remarkably, post-mortem analyses of brain pathology (e.g., plaques and tangles) from participants who died showed that purpose in life moderated links between brain-based pathology and levels of cognitive function while respondents were still alive. That is, among those showing high levels of brain pathology, better cognitive function was evident among those who reported higher levels of purpose in life compared to those with comparable brain pathology but with lower levels of purpose in life (Boyle et al. 2012).

Another major national longitudinal study known as HRS (Health and Retirement Study) provided prospective evidence that older adults with higher levels of purpose in life had reduced risk of stroke (Kim et al. 2013a) as well as reduced risk of myocardial infarction among those with coronary heart disease (Kim et al. 2013b). This same study also found that older adults with higher levels of purposeful engagement were more likely to engage in preventive health behaviors, such as cholesterol tests and cancer screenings (Kim et al. 2014) relative to age peers with lower levels of purposeful in life. Findings from another major national longitudinal study known as MIDUS (Midlife in the U.S.) corroborated the evidence that purpose in life reduces risk of mortality across adult life (Hill and Turiano 2014).

Other studies have probed eudaimonic well-being as a moderating influence that affords a protective resource vis-à-vis targeted challenge. For example, Friedman and Ryff (2012) showed that two aspects of well-being (purpose in life and positive relations) buffered against adverse physiological consequents of later-life comorbidity (multiple chronic conditions). Incrementing chronic conditions (e.g. hypertension, arthritis) are common with aging; many of which fuel inflammatory processes that add further risk for subsequent adverse health outcomes. Indeed, higher levels of chronic conditions were found to predicte elevated levels of interleukin-6 (IL-6) and C-reactive protein (CRP). However, those with high comorbidity, older adults reporting high purposeful engagement and high positive relations showed lower levels of these inflammatory markers compared to those with high comorbidity who reported low purpose and low social connections. A related study focused on sleep problems, which are known to increase with aging. Again, among older women who reported higher levels of eudaimonic well-being (all dimensions except autonomy), lower levels of disrupted sleep were evident (Phelan et al. 2010). Both studies underscore the protective role of eudaimonic well-being vis-à-vis challenges of aging.

Viewed collectively, these aging studies first offer longitudinal evidence that certain aspects of eudaimonic well-being (purpose in life, personal growth) show later life vulnerabilities – that is, losses are evident. These declines may reflect the “structural lag” problem (Riley et al. 1994), which asserts that the added years of life many now experience are not accompanied by opportunities for meaningful roles and activities. Effectively, the surrounding social structures (in work, family, and community life) lag behind the added years of life that many now experience. Second, evidence of later life decline in purposeful engagement co-exists with notable variability among older adults. For those who maintain high levels of purpose in life, an array of health benefits (reduced risk for multiple disease outcomes) as well as increased longevity are evident. Eudaimonic well-being also offers a protective buffer against the physiological consequences of comorbidity and age-related risk for increased sleep disturbance. None of these scientific advances could have been documented without the availability of a eudaimonic model of well-being (Ryff 1989) in the empirical arena, thereby opening the way to investigate its correlates and consequents.

3.2 Challenges of inequality

Protective benefits of eudaimonic well-being have also been examined in contexts of social inequality. The background literature, well known in economic and health circles, shows that those with lower socioeconomic standing (educational attainment, occupational status, income) are at increased risk for diverse health problem (Adler et al. 1999; Marmot 2005). Reports of well-being also reveal a gradient, whereby those with higher levels of educational attainment report higher levels of diverse aspects of eudaimonia (Ryff 2016; Ryff et al. 2015a). The directional nature of this relationship is not known (does educational advancement enhance well-being, or does well-being motivate educational pursuits?), although it is reasonable to construe opportunities for higher education as providing knowledge, skills, and economic resources whereby individuals can better manage their lives, pursue their goals, and make the most of their talents and capacities. But again, variability within educational strata is notably evident – i.e., some individuals who lack college or university degrees report high levels of eudaimonic well-being, thereby paralleling the aging scenario described in the preceding section. In addition, health benefits are evident among the educationally disadvantaged who report higher eudaimonic well-being.

Using MIDUS data, Morozink et al. (2010) documented that those with lower educational status had higher levels of the inflammatory marker interleukin-6, which is implicated in multiple disease outcomes (cardiovascular disease, cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, osteoporosis). However, a moderating/buffering effect was evident among less educated adults who reported high eudaimonic well-being. That is, those with limited education who had higher levels of multiple aspects of well-being showed lower levels of IL-6 compared to their same education counterparts reporting lower well-being. A further study (Tsenkova et al. 2007) showed links between income and cross-time changes in glycosylated hemoglobin (HbAlc), a marker of glycemic control connected to Type 2 diabetes. Lower incomes predicted worse (higher) cross-time profiles of HbAlc, but measures of well-being (purpose in life, personal growth, positive affect) moderated this relationship, again underscoring the importance of psychological factors as protective resources vis-à-vis inequality. More recently longitudinal profiles of eudaimonic well-being (Ryff et al. 2015b) reveal notable stability over a 9–10 year period – some are persistently high in their levels of eudaimonic well-being across time while others are persistently low. These differing profiles illustrate cumulative processes that predict cross-time health change: those with persistently high well-being showed gains in subjective health, along with better profiles in chronic conditions, health symptoms, and functional health over time compared to those with persistently low well-being. Returning to the theme of buffering influences, persistently high well-being also moderated the link between educational status and unfolding health changes. Thus, less educated adults with persistently high well-being were protected against certain adverse health changes observed for their low education counterparts with persistently low well-being.

Low socioeconomic standing is frequently evident among racial/ethnic minorities. However, eudaimonic well-being between majority and minority groups in MIDUS reveals interesting and counter-intuitive findings. Given the joint challenges of racism and inequality, compromised eudaimonic well-being might be expected among U.S. blacks compared to whites. What the science reveals is that ethnic monitory status is a positive predictor of eudaimonic well-being compared to white majority status (Ryff et al. 2003), after controlling for other factors. This finding suggests that the challenges of minority life may actually hone (strengthen) qualities such as purpose in life and personal growth. Additional work from MIDUS has documented that U.S. blacks have higher rates of “flourishing” (defined as having high levels of well-being and low levels of mental distress) compared to U.S. whites (Keyes 2009); the differences would be even more marked were it not for perceptions of discrimination. Bringing biomarkers into the tale, MIDUS investigators have shown that perceived discrimination predicts healthier profiles of diurnal cortisol (steeper diurnal decline) among African American compared to white respondents (Fuller-Rowell et al. 2012). Such findings suggest that the awareness of racism in daily life may have protective benefits for health. Together, these race-related findings underscore themes of resilience, despite the challenges of inequality and racism, though further research is needed to explicate such results and to examine their replicative consistency.

3.3 Probing neural and genetic mechanisms

The neural correlates of eudaimonic well-being are receiving scientific attention. An initial study using electrophysiological indicators showed that adults reporting higher levels of eudaimonic well-being showed greater left than right superior frontal activation in response to emotion stimuli (Urry et al. 2004), after adjusting for reported levels of hedonic well-being. A recent MIDUS study showed that those with higher levels of purpose in life had more rapid brain-based emotional recovery (measured in terms of eyeblink response) from negative stimuli (Schaefer et al. 2013). Other studies have used functional magnetic resonance imaging. VanReekum et al. (2007) examine amygdala activation in response to negative (compared to neutral) stimuli, finding that those who were faster to evaluate negative information showed increased left and right amygdala activation. These patterns varied, however, depending on composite profiles of eudaimonic well-being. Those with higher eudaimonia were slower to evaluate such information, and they showed reduced amygdala activation as well as increased ventral anterior cingulate cortex activity, possibly recruited in response to aversive stimuli.

In recent MIDUS findings, neural responses to positive stimuli were examined (Heller et al. 2013). Links were evident between sustained activity in reward circuitry (ventral striatum and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex) and higher eudaimonic well-being (composite) – effectively those with sustained activation of reward circuitry in response to positive stimuli had higher eudaimonia. Further the nexus between sustained reward circuitry and eudaimonia was linked with lower diurnal cortisol output (measured 4 times a day across 4 days). Together, these outcomes underscore the interplay between brain mechanisms, subjective experiences of well-being, and stress hormones. Finally, eudaimonic well-being (personal growth, positive relations, purpose in life) has been linked with insular cortex volume (Lewis et al. 2014). Those with higher well-being have greater volume of right insular cortex grey matter, which is involved in a variety of higher-order functions. Overall, these brain-based inquiries (see Ryff et al. 2016 for more detail) are explicating underlying neural mechanisms involved in experiences of eudaimonia.

Recent research has also linked well-being (hedonic and eudaimonic) to gene expression, focused on the conserved transcriptional response to adversity (CTRA), which is characterized by up-regulated expression of pro-inflammatory genes and down-regulated expression of antibody synthesis genes. A first study (Fredrickson et al. 2013) showed divergent transcriptome profiles for hedonic versus eudaimonic well-being. Specifically, high hedonic well-being was associated with CTRA up regulation (increased expression of pro-inflammatory genes and decreased expression of antibody synthesis genes). In contrast, those high in eudaimonic well-being showed CTRA down regulation (i.e., decreased expression of pro-inflammatory genes and increased expression of antibody synthesis genes). These patterns were independent of demographic, health, and behavioral risk factors. Eudaimonia thus appeared to convey health-related benefits related to gene expression not evident for hedonia. A subsequent study, using more detailed measures of eudaimonic well-being (Fredrickson et al. 2015), showed reduced CTRA expression for all but one of the six dimensions of well-being, again after adjusting for demographic characteristics, health-related confounders, and RNA indicators of leukocyte subset distribution. Another recent investigation (Cole et al. 2015) found CTRA expression to be up-regulated in association with loneliness, but again, down-regulated in association with eudaimonic well-being. Such findings point to the potential utility of targeting health risks associated with social isolation by promoting meaning and purpose in life.

In sum, extensive findings document eudaimonic well-being has become a tractable topic in basic science research. Thanks to the availability of conceptually-grounded, quantitative assessment tools, meaningful linkages between well-being and diverse challenges (aging, inequality) have been identified and connected to diverse health outcomes (morbidity, mortality, biological risk factors). Further inquiries are illuminating linkages between eudaimonia and brain-based processes as well as gene expression. These emerging lines of inquiry and others (see Ryff, 2014) have import for public policy, particularly the allocation of resources to improve the human condition. Arguably, the promotion of well-being as an avenue to improve health and length of life may be no less promising than the development of pharmaceutical interventions to advance the nation’s health. The next section below summarizes active intervention efforts to promote eudaimonic well-being.

4 The promotion of eudaimonia to improve lives

Growing evidence suggests that eudaimonic well-being is modifiable (Ruini and Ryff 2016; Ryff 2014). Before considering relevant examples, it should be emphasized that the lack of well-being increases subsequent risk for mental illness (Keyes 2002), and further that cross-time gains in well-being predict cross-time declines in mental illness (Keyes et al. 2010). Thus, awareness is growing that promoting positive mental health has important public health significance. In treating mental health problems, it has also become clear that full recovery involves more than the reduction of symptoms or absence of psychological distress; it must also include the promotion of experiences of well-being (Fava et al. 2007; Ruini and Fava 2012).

One prominent example is “well-being therapy” (Fava 1999; Fava et al. 1998), which makes explicit use of eudaimonic well-being. Conceived as an addition to cognitive behavioral therapy in treating major depression, the overarching goal is to promote positive psychological experiences for patients’ as a way of preventing relapse. The intervention requires keeping daily diaries of positive happenings, which then become the focus of therapy wherein patients learn how to enrich awareness of such experiences by linking them to related dimensions in the Ryff model of well-being, and importantly, to prevent premature curtailment of these experiences. Initial finds documented improved remission profiles among those who received well-being therapy, and longitudinal follow-up further showed that relapse was prevented over a six year period (Fava et al. 2004). Well-being therapy was also found to be effective in treating anxiety disorders (Fava et al. 2005; Ruini et al. 2015; Ruini and Fava 2009), again with long-lasting effects.

Outside the clinical context, eudaimonia may play an important role in prevention mental illness and psychological distress in the broader population. A promising context for such work in adolescence is the school. Ruini et al. (2006) adapted well-being therapy for school settings with the goal of preventing the development of depression, especially among adolescent girls. Comparison of students receiving the intervention with an attention-placebo group revealed significant improvements in personal growth, along with reductions in distress (Ruini et al. 2009). Another controlled investigation in schools showed that well-being therapy produced significant improvements in autonomy and friendliness, whereas an anxiety management intervention ameliorated anxious and depressive symptoms (Tomba et al. 2010)). Further school interventions are summarized in Ruini and Ryff (2016).

At the other end of the life course, the promotion of eudaimonia among older adults in the community has been of interest in a program known as Lighten Up! (Friedman et al. 2015). Later life comes with many challenges (loss of roles, loss of significant others, health events) that may increase vulnerability to depression. This program, conducted over a period of eight weeks, involves discussion of the importance of well-being in later life, the sharing of positive memories, and engagement in exercises designed to promote eudaimonia as well as to deal with difficult life challenges. Pre-post comparisons for the initial pilot study showed gains in most aspects of eudaimonic well-being as well as life satisfaction as well as reductions in depressive and physical symptoms and sleep complaints. These improvements were particularly evident among individuals with lower levels of eudaimonic well-being prior to the intervention. This work has been expanded to include further groups of older adults in multiple community contexts.

More interventions, in clinical and community contexts, are detailed in Ryff (2014). Collectively, such work shows that eudaimonic well-being can be promoted, thus pointing to important new directions in research translation and public health education. It is worth noting that none of the conceptual formulations drawn on to create the model of eudaimonic well-being described herein (Ryff 1989) were explicitly concerned with how to promote positive functioning; rather they sought to articulate the defining features of optimal human functioning. Similarly, Aristotle’s writings were not a treatise in how to promote virtuous living; rather his objective was to articulate varieties of virtue. Thanks to contemporary science and practice, however, the possibility of promoting ever wider experiences of eudaimonia for ever larger segments of society is becoming a viable objective.

5 Two future directions

The above reported findings need further work to examine their replicative consistency as well as extensions in multiple directions (longitudinal inquiries, incorporation of additional moderating and mediating influences). To broaden future science and deepen its relevance for human betterment, two less obvious avenues for new work are suggested. The first is negative in tone and addresses the contemporary problem of greed among privileged elites and what it means for the well-being of those who are socioeconomically disadvantaged. The second is positive in tone and addresses the potential role of the arts and humanities to enhance eudiamonic well-being, including among those suffering from inequality or dealing with significant life adversity.

Understanding the Sources and Broader Consequences of Greed at the Top

Research on health inequalities provides ample evidence, as described above, that those lacking educational attainment, economic advantage, and occupational opportunities experience higher stress exposures and have poorer health. Indeed, most science on health inequalities has focused on the costs borne by those at lower positions in status hierarchies. Far less is known about the characteristics (motivations, behavior) of those at the top, some of whom, by their actions may undermine the eudaimonic well-being of others below them. That is, greed may be a fundamental force that is fueling the growing problem of inequality, now evident on a global scale (Piketty 2014; Wang & Murnighan 2011). Over 200 years ago, Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations (1981/1776) distilled the case for self-interest and capitalism, but even he recognized the problem of greed, which he depicted as the limitless appetites of the vain and insatiable (see Wight, 2005). For Smith, prudent and virtuous self-interest was fundamentally distinct from greed and selfishness. In the late middle ages, Dante’s poetic masterpiece, The Divine Comedy, included the sins of greed and gluttony, along with fraud and dishonesty, in his nine circles of hell (Dante/Longfellow/Amari-Parker 2006). Going back still further, the ancient Greeks were explicitly concerned about problems of greed and injustice (Balot 2001), which they saw as violating virtues of fairness and equality and in so doing, contributing to civic strife. Both the ancient Greeks and Romans called for public criticism and censuring of greed.

What is the import of these distant views on greed for contemporary science? As a core human failing, they underscore that greed demands a wide-ranging approach. Extreme cases of it, such as fraudulent misconduct (e.g., Bernie Madoff’s Ponzi scheme, the fall of Enron), invoke the legal system to identify and punish rapacious greed. Far more common, however, are forms of greed that do not break laws, such as wildly disproportionate bonuses of top executives relative to the salaries of workers below them. These discrepancies likely have pernicious impacts, but they are insufficiently studied. Multiple scientific disciplines are needed to investigate behavioral enactments of greed and their sequelae for individuals, communities, and societies.

Psychologists of many varieties are making valuable contributions. From a psychoanalytic perspective, Nikelly (2006) probed the etiology of selfish gratification for amassing wealth and the worship of money through fraudulent and deceptive tactics. Approaches to the treatment were also considered. In the empirical arena, motivational psychologists have examined “the dark side of the American Dream” (Kasser & Ryan 1993) to show that those motivated primarily by extrinsic factors (financial success) had lower well-being and adjustment compared to those motivated by less materialistic values. Social psychologists have used experimental procedures to show that those with higher social class standing show increased entitlement and narcissism (Piff 2014). Experimental and naturalistic studies have also shown that upper-class respondents behave more unethically than lower-class individuals (Piff et al. 2012). The sense of power has been found to mediate the relationship between high social class standing and selfishness (Dubois et al. 2015).

Bridging psychology, moral philosophy, economics, and sociology, Côté et al. (2013) showed that upper-class respondents are more likely than lower-class respondents to choose utilitarian options (maximizing the greatest good for the greatest number) in resolving moral dilemmas, and relatedly, to show less empathy. Alternatively, Rand et al. (2012) used economic games to make argue that cooperation is intuitive (automatic) because it is typically advantageous in daily life, whereas greed requires greater calculation. As a counterpoint, economists have focused on work contexts in the form of “values-based organizations” wherein core objectives (motivations) are intrinsically tied to ideals greater than profit and material incentives (Bruni & Smerilli, 2009). These factors are then studied as a window on why organizations flourish, or deteriorate, based on who stays or exists from the organization over time. In the public policy arena, contemporary scholars have re-examined the meaning of civil society and its import for praxis in health and social care (Scambler et al. 2014). Focused on England and Wales, they concluded that a new “class/command dynamic’ has emerged in our era of financial capitalism, which has led to oligarchic rule and resistance to the traditional health and social care commitments of civil society. Similarly, Tomatis (2005) examined the forces working against the primary prevention of cancer, particularly related to carcinogenic exposures and chemical pollutants. Included are a perverse combination of factors: extreme poverty in certain countries, the irreducible selfishness of rich countries, and the greed of multinational corporations. What Tomatis calls for is the rediscovery of ethical principles.

Returning to the focus of this article, namely, how eudiamonia matters for health, a key direction for future research is to investigate the scope of greed among privileged elites, revealed by behavioral priorities and choices, and its role in undermining the health and well-being (self-realization, personal growth) of those below them in status hierarchies. Such inquiry can draw on the above research to examine facets of greed (extrinsic motivation, sense of entitlement, narcissism, need for power, selfishness) and unethical behavior, but to bring these issues into real-world contexts. Importantly, such work needs to encompass manifestations of greed mean for others – that is, researchers need to shine a spotlight on the consequences of self-serving vs. beneficent senior leaders for others, not just in the corporate world but also in science, local and national governments, and public policy arenas. Salary differentials across occupational hierarchies are already studied by economists, these kinds of data need to be linked to the health and well-being of employees at all levels. Do self-interested and greedy leadership styles and priorities translate to more stressed and unhealthy employees? Such queries take research on health inequalities in new directions, signaling a shift away from repeated documentation that socioeconomic disadvantage predicts higher morbidity and earlier mortality and toward assessment of the scope of greed at the top and its impact on the lives of those in lower echelons. Research of this nature would be a scientific enactment of convictions held by the ancient Greeks and Romans who called for public censuring of greed.

Bringing the Arts and Humanities into Research on Health and Well-Being

In juxtaposition to studying greed as a malevolent force that likely undermines the good lives of many, a positive future direction calls for bringing the arts and humanities into research on health and well-being. Several areas of inquiry support the bridging of these domains, which may be particularly urgent now when the arts and humanities are in decline (Hanson & Health 1998; Nussbaum 1997). Within universities, fewer students major in literature, philosophy, art, and music. Outside of the academy, fewer citizens partake of art exhibits or the performing arts (Cohen 2013). Within local communities, financially constrained schools eliminate music and art as dispensable aspects of the curriculum. This diminishment of the arts and humanities cuts people off from important sources of moral and ethical identity (Hadot 1995; Taylor 1989) with likely consequences for well-being and civil society.

Despite such trends, multiple opportunities for fruitful connections between the arts and humanities with those studying health and well-being are at hand. First, increasing emphasis is now given to the arts in medical training and in therapy, healthcare, and community life. This direction is exemplified by the new field of “health humanities” (Crawford et al. 2015), along with a recent report from the Royal Society for Public Health in the United Kingdom, entitled “The Arts, Health, and Well-Being” (2013). Detailed within the document are benefits of the humanities (philosophy, theology, literature, music, poetry, film) for human health and public policy. Similarly, the field of public health in the U.S. has seen advocacy for deepened understanding of art-based interventions (Stuckey & Nobel 2010). Biomedical researchers, in turn, are investigating diverse related topics, such as the effects of choir singing or listening on stress-related biomarkers and emotion (Kruetz, Bongard, Rohrmann et al. 2004).

Second, from within the arts and humanities, there is growing interest in demonstrating the value of these fields for nurturing well-lived lives and good societies via their influences on promoting key human ideals and the meaning-making practices of culture (Small 2013; Edmondson 2004, 2015). From within the world of museums, there is growing interest among directors and curators in how to make their holdings of greater relevance to the general public (Mid Magasin 2015), including among those who are economically and educationally disadvantaged, or even incarcerated. Such efforts bring principles of social justice in the museum world. Related activities include thinking in new ways about how encounters with the arts, broadly defined, can provoke and impact those who partake of them (see also de Botton 1997, 2013).

Third, within the field of education, there is heightened interest in how music, literature, the visual arts, and drama contribute to diverse aspects of well-being (Lomas 2016), including experiences of self-realization and life-long experiences of continued personal growth (Ryff 2016). These initiatives signal a return to insights from John Dewey (1899) about how to educate children as well as about how we experience art and how it matters in our lives (Dewey 1934). The history of democracy attests to the central role of the arts in teaching critical thinking, including the ability to criticize authority as well as acquire capacities for human empathy (Nussbaum 2010). When education is construed primarily for economic growth, parents are reluctant to see their children become artists, dancers, musicians and poets; instead, they want doctors, lawyers, scientists, and technology experts. Human lives are thus increasingly seen as instruments for gain. Left behind is the teaching of poetry and literature as vehicles for understanding the self and others in a heterogeneous world. A recent claim among educators is that the promotion of well-being is or should be the primary goal of higher education (Harward 2016).

Taken together, these diverse happenings suggest that the time has come for the social and behavioral sciences as well as biomedical and health sciences to broaden the purview of their endeavors to include research on the role of the arts and humanities in promoting human health and well-being, perhaps particularly in contexts of adversity and economic disadvantage. Indeed, a case can be made that what lies behind the poorer health of those with limited incomes and educational opportunities is not just greater exposures to life stress and inadequate resources for dealing with them, but also fewer encounters with the arts that might serve as protective buffers and sources of inspiration or relief against abject realities. The central questions awaiting future scientific scrutiny are whether the arts and humanities nurture experiences of eudaimonia and thereby, contribute to better health and longer lives across all segments of society.

6 Summary

This article put forth a model of human well-being that emerged from perspectives in clinical, developmental, existential, and humanistic psychology concerned with distilling the contours of optimal human functioning. These formulations were also linked to Aristotle’s conception of eudaimonia as the highest of all human goods. Empirical studies documenting the health benefits of eudaimonia were then reviewed. A first set of findings showcased the protective health benefits of purposeful and engaged living vis-à-vis the challenges of growing old. A second set of findings showed the buffering effects of eudaimonic well-being in the face of social inequalities. Understanding the mechanisms behind these findings focused on recent findings linking eudaimonia to neuroscience and gene expression. Given the health benefits of eudaimonic well-being, intervention strategies in clinical and educational contexts designed to promote such experiences were briefly reviewed. The final section advocated for two new directions in future research – one is designed to probe the problem of greed among privileged elites as a force that likely undermines to well-being of those in lower status positions, and another intended to bring greater scientific attention to the role of the arts and humanities in nurturing experiences of purposeful engagement, meaning living, and self-realization.

Acknowledgments

The MIDUS 1 study (Midlife in the U.S.) was supported by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Successful Midlife Development. The MIDUS 2 research was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (P01-AG020166) to conduct a longitudinal follow-up of the MIDUS 1 investigation. The biological research was further supported by the following grants M01-RR023942 (Georgetown), M01-RR00865 (UCLA) from the General Clinical Research Centers Program and UL1TR000427 (UW) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

JEL Classification Code: I10 (Health, General)

Conflict of Interest: The author declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Reference List

- Adler NE, Marmot MG, McEwen BS, Stewart J. Annals of the New York academy of sciences. Vol. 896. New York Academy of Sciences; New York: 1999. Socioeconomic status and health in industrialized nations: Social, psychological, and biological pathways. [Google Scholar]

- Allport GW. Pattern and growth in personality. Holt, Rinehart, & Winston; New York: 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Antonovsky A. Health, stress, and coping. 1st. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 1979. (The jossey-bass social and behavioral science series). [Google Scholar]

- Antonovsky A. Unraveling the mystery of health. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Aristotle . The Nicomachean Ethics. Oxford University Press; New York: 1925. [Google Scholar]

- Balot RK. Greed and injustice in classical Athens. Princeton University Press; Princeton, NJ: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Becker LC. Good lives: Prolegomena. Social Philosophy & Policy. 1992;9:15–37. doi: 10.1017/S0265052500001382. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle PA, Barnes LL, Buchman AS, Bennett DA. Purpose in life is associated with mortality among community-dwelling older persons. Psychosom Med. 2009;71:574–579. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181a5a7c0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle PA, Buchman AS, Barnes LL, Bennett DA. Effect of a purpose in life on risk of incident Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment in community-dwelling older persons. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:304–310. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle PA, Buchman AS, Wilson RS, Yu L, Schneider JA, Bennett DA. Effect of purpose in life on the relation between Alzheimer disease pathologic changes on cognitive function in advanced age. JAMA Psychiatry. 2012;69:499–506. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruni L, Smerilli A. The value of vocation: The crucial role of intrinsically motivated people in values-based organizations. Review of Social Economy. 2009;67:271–288. [Google Scholar]

- Bühler C. The curve of life as studied in biographies. J Appl Psychol. 1935;43:653–673. doi: 10.1037/h0054778. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P. The New York Times. 2013. Sep, A new survey finds drop in art attendance; p. 26. [Google Scholar]

- Cole SW, Levine ME, Arevalo JMG, Ma J, Weir DR, Crimmins EM. Loneliness, eudaimonia, and the human conserved transcriptional response to adversity. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;62:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Côté S, Piff PK, Willer R. For whom do the ends justify the means? Social class and utilitarian moral judgment. J of Personality and Social Psych. 2013;104:490–503. doi: 10.1037/a0030931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford P, Brown B, Baker C, Tischler V, Abrams B. Health humanities. Palgrave Macmillan: NY: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dante . In: The divine comedy. Longfellow HW, translator; Amari-Parker A, editor. Chartwell Books, Inc.; NY, NY: 2006/13/08. [Google Scholar]

- de Botton A. How Proust can change your life: Not a novel. Vintage; Visalia, CA: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- de Botton A, Armstrong A. Art as therapy. Phaidon Press; London UK: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey J. The school and society. Southern Illinois University Press; Carbondale, IL: 1899. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey J. Art as experience. Penguin; NY, NY: 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Dubois D, Rucker DD, Galinsky AD. Social class, power, and selfishness: When and why upper and lower class individuals behave unethically. J of Personality and Social Psych. 2015;108:436–449. doi: 10.1037/pspi0000008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmundson M. Self and soul: A defense of ideals. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson M. Why read? Bloomsbury; NY, NY: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Identity and the life cycle: Selected papers. Psychol Issues. 1959;1:1–171. [Google Scholar]

- Fava GA. Well-being therapy: Conceptual and technical issues. Psychother Psychosom. 1999;68:171–179. doi: 10.1159/000012329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava GA, Rafanelli C, Cazzaro M, Conti S, Grandi S. Well-being therapy: A novel psychotherapeutic approach for residual symptoms of affective disorders. Psychol Med. 1998;28:475–480. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797006363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava GA, Ruini C, Belaise C. The concept of recovery in major depression. Psychol Med. 2007;37:307–317. doi: 10.1017/s0033291706008981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava GA, Ruini C, Rafanelli C, Finos L, Conti S, Grandi S. Six-year outcome of cognitive behavior therapy for prevention of recurrent depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1872–1876. doi: 10.1176/ajp.161.10.1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava GA, Ruini C, Rafanelli C, Finos L, Salmaso L, Mangelli L, Sirigatti S. Well-being therapy of generalized anxiety disorder. Psychother Psychosom. 2005;74:26–30. doi: 10.1159/000082023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankl VE. Man’s search for meaning: An introduction to logotherapy. Beacon Press; Boston, MA: 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, Grewen KM, Algoe SB, Firestine AM, Arevalo JMG, Ma J, Cole SW. Psychological well-being and the human conserved transcriptional response to adversity. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, et al. A functional genomic perspective on human well-being. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:13684–13689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305419110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman EM, Ruini C, Foy R, Jaros L, Sampson H, Ryff CD. Lighten up! A community-based group intervention to promote psychological well-being in older adults. Aging Ment Health. 2015 doi: 10.1080/13607863.2015.1093605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman EM, Ryff CD. Living well with medical comorbidities: A biopsychosocial perspective. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2012;67:535–544. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller-Rowell TE, Doan SN, Eccles JS. Differential effects of perceived discrimination on the diurnal cortisol rhythm of African Americans and Whites. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37:107–118. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadot P. Philosophy as a way of life. Blackwell; Oxford, England: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson VD, Health J. Who killed Homer? The demise of classical education and the recovery of Greek wisdom. Encounter Books; NY, NY: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Harward DW. Bringing Theory to Practice. Washington DC: 2016. Well-being and higher education: A strategy for change and the realization of education’s greater purposes. [Google Scholar]

- Heller AS, van Reekum CM, Schaefer SM, Lapate RC, Radler BT, Ryff CD, Davidson RJ. Sustained ventral striatal activity predicts eudaimonic well-being and cortisol output. Psychol Sci. 2013;24:2191–2200. doi: 10.1177/0956797613490744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill PL, Turiano NA. Purpose in life as a predictor of mortality across adulthood. Psychol Sci. 2014;25:1482–1486. doi: 10.1177/0956797614531799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson DN. Personality research form manual. Research Psychologists Press; Goshen, NY: 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson DN. Jackson personality inventory manual. Research Psychologists Press; Goshen, NY: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Jahoda M. Current concepts of positive mental health. Basic Books; New York: 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Jung CG. Modern man in search of a soul. Harcourt, Brace & World; New York: 1933. [Google Scholar]

- Kasser T, Ryan RM. A dark side of the American dream: correlates of financial success as a central life aspiration. J of Pers Soc Psychol. 1993;65:410–422. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.65.2.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes CLM. The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43:207–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes CLM. The Black - White paradox in health: Flourishing in the face of social inequality and discrimination. J Pers. 2009;77:1677–1706. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes CLM, Dhingra SS, Simoes EJ. Change in level of positive mental health as a predictor of future risk of mental illness. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:2366. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.192245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim ES, Strecher VJ, Ryff CD. Purpose in life and use of preventive health care services. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:16331–16336. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1414826111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim ES, Sun JK, Park N, Kubzansky LD, Peterson C. Purpose in life and reduced risk of myocardial infarction among older U.S. Adults with coronary heart disease: A two-year follow-up. J Behav Med. 2013b;36:124–133. doi: 10.1007/s10865-012-9406-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim ES, Sun JK, Park N, Peterson C. Purpose in life and reduced stroke in older adults: The health and retirement study. J Psychosom Res. 2013a;74:427–432. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreutz G, Bongard S, Rohrmann S, Hdapp V, Brebe D. Effects of choir singing and listening on secretory immunoglobulin A, cortisol, and emotion state. J of Beh Med. 2004;27:623–635. doi: 10.1007/s10865-004-0006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis GJ, Kanai R, Rees G, Bates TC. Neural correlates of the “good life”: Eudaimonic well-being is associated with insular cortex volume. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2014;9:615–618. doi: 10.1093/scan/nst032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomas T. Positive art: Artistic expression and appreciation as an exemplary vehicle for flourishing. Review of General Psychology. 2016;20:171–182. [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M. Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet. 2005;365:1099–1104. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)71146-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslow AH. Toward a psychology of being. 2nd. Van Nostrand; New York: 1968. [Google Scholar]

- MiD Magasin. Why museums? 32, Marts. Museumformidlere i Danmark; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Morozink JA, Friedman EM, Coe CL, Ryff CD. Socioeconomic and psychosocial predictors of interleukin-6 in the MIDUS national sample. Health Psychol. 2010;29:626–635. doi: 10.1037/a0021360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neugarten BL. Personality change in late life: A developmental perspective. In: Eisodorfer C, Lawton MP, editors. The psychology of adult development and aging. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 1973. pp. 311–335. [Google Scholar]

- Nikelly A. The pathogenesis of greed: Causes and consequences. Int J of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies. 2006;3:65–78. doi: 10.1002/aps.50. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Norton DL. Personal destinies: A philosophy of ethical individualism. Princeton University Press; Princeton, NJ: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum MC. Not for profit: Why democracy needs the humanities. Princeton University Press; Princeton NJ: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Phelan CH, Love GD, Ryff CD, Brown RL, Heidrich SM. Psychosocial predictors of changing sleep patterns in aging women: A multiple pathway approach. Psychol Aging. 2010;25:858–866. doi: 10.1037/a0019622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piff PK. Wealth and the inflated self: class, entitlement, and narcissism. Personality and Soc Psych Bulletin. 2014;40:34–43. doi: 10.11770/0146167213501699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piff PK, Stancato DM, Côté S, Mendoza-Denton R, Keltner D. Higher social class predicted increased unethical behavior. Proceedings of the National Academies of Science (PNAS) 2012;109:4086–4091. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118373109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piketty T. In: Capital in the twenty-first century. Goldhammer A, translator. Belknap Press; Cambridge, MA: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rand DG, Greene JD, Nowak MA. Spontaneous giving and calculated greed. Nature. 2012;498:427–430. doi: 10.1038/nature11467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley MW, Kahn RL, Foner A. Age and structural lag. Wiley; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers CR. On becoming a person. Houghton Mifflin; Boston, MA: 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Royal Society and Public Health Working Group. Arts, health, and well-being beyond the millennium: How far have we come and where do we want to go? Royal Society for Public Health; London UK: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ruini C, Albieri E, Vescovelli F. Well-Being Therapy: State of the art and clinical exemplifications. J Contemp Psychother. 2015;45:129–136. doi: 10.1007/s10879-014-9290-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruini C, Belaise C, Brombin C, Caffo E, Fava GA. Well-being therapy in school settings: A pilot study. Psychother Psychosom. 2006;75:331–336. doi: 10.1159/000095438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruini C, Fava GA. Well-being therapy for generalized anxiety disorder. J Clin Psychol. 2009;65:510–519. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruini C, Fava GA. Role of well-being therapy in achieving a balanced and individualized path to optimal functioning. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2012;19:291–304. doi: 10.1002/cpp.1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruini C, et al. School intervention for promoting psychological well-being in adolescence. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2009;40:522–532. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruini C, Ryff CD. Using eudaimonic well-being to improve lives. In: Wood AM, Johnson J, editors. The Wiley handbook of positive clinical psychology: An integrative approach to studying and improving well-being. Wiley-Blackwell; Hoboken, NJ: 2016. pp. 153–166. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;57:1069–1081. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD. Psychological well-being revisited: Advances in the science and practice of eudaimonia. Psychother Psychosom. 2014;83:10–28. doi: 10.1159/000353263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD. Eudaimonic well-being and education: Probing the connections. In: Harward D, editor. Well-being and higher education: A strategy for change and the realization of education’s greater purposes. Rowman & Littlefield; Lanham, MD: 2016. pp. 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, Friedman E, Fuller-Rowell T, Love G, Morozink J, Radler B, Tsenkova V, Miyamoto Y. Varieites of resilience in MIDUS. Social and Personality Psych. 2012;6:792–806. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2012.00462.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, Heller AS, Schaefer SM, Van Reekum C, Davidson RJ. Purposeful engagement, healthy aging, and the brain. Current Behavioral Neuroscience Reports. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s40473-016-0096-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, Keyes CLM, Hughes DL. Status inequalities, perceived discrimination, and eudaimonic well-being: Do the challenges of minority life hone purpose and growth? J Health Soc Behav. 2003;44:275–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, et al. Culture, inequality, and health: Evidence from the MIDUS and MIDJA comparison. Cult Brain. 2015a;3:1–20. doi: 10.1007/s40167-015-0025-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, Radler BT, Friedman EM. Persistent psychological well-being predicts improved self-rated health over 9–10 years: Longitudinal evidence from MIDUS. Health Psychol Open. 2015b;2 doi: 10.1177/2055102915601582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, Singer BH. The contours of positive human health. Psychol Inq. 1998;9:1–28. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli0901_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, Singer BH. Know thyself and become what you are: A eudaimonic approach to psychological well-being. J Happiness Stud. 2008;9:13–39. doi: 10.1007/s10902-006-9019-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scambler G, Scambler S, Speed E. Civil society and the Health and Social Care Act in England and Wales: Theory and praxis for the twenty-first century. Social Science and Medicine. 2014;123:210–216. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer SM, Boylan JM, van Reekum CM, Lapate RC, Norris CJ, Ryff CD, Davidson RJ. Purpose in life predicts better emotional recovery from negative stimuli. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e80329. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small H. The value of the humanities. Oxford University Press; Oxford UK: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. An inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations. In: Campell RH, Skinner AS, editors. Two volumes. Indianapolis, IN: Liberty Press; 1981/1776. reprinted by. [Google Scholar]

- Springer KW, Pudrovska T, Hauser RM. Does psychological well-being change with age? Longitudinal tests of age variations and further exploration of the multidimensionality of Ryff’s model of psychological well-being. Soc Sci Res. 2011;40:392–398. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuckey HL, Nobel J. The connection between art, healing, and public health: A review of current literature. Amer J of Public Health. 2010;100:254–263. doi: 10.2105/ALPH.2008.156497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor C. Sources of the self: The making of modern identity. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, England: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Tomatis L. Primary prevention of cancer in relation to science, sociocultural trends and economic pressures. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2005;31:227–232. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomba E, et al. Differential effects of well-being promoting and anxiety-management strategies in a non-clinical school setting. J Anxiety Disord. 2010;24:326–333. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsenkova VK, Love GD, Singer BH, Ryff CD. Socioeconomic status and psychological well-being predict cross-time change in glycosylated hemoglobin in older women without diabetes. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:777–784. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318157466f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urry HL, et al. Making a life worth living: Neural correlates of well-being. 2004;15:367–372. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Reekum CM, et al. Individual differences in amygdala and ventromedial prefrontal cortex activity are associated with evaluation speed and psychological well-being. J Cogn Neurosci. 2007;19:237–248. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2007.19.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Murnighan JK. On greed. The Academy of Management Annals. 2011;5:279–316. doi: 10.1080/19416520.2011.588822. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins LM. Panel analysis: Latent probability models for attitude and behavior processes. Jossey-Bass; Oxford, England: 1973. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Constitution of the World Health Organization: Basic documents. Geneva, Switzerland: 1948. Author Retrieved March 11, 2016 from http://www.who.int/about/mission/en/ [Google Scholar]

- Wright JB. Adam Smith and greed. J of Private Enterprise. 2005;21:46–58. [Google Scholar]