Abstract

Over the past several decades, Puerto Ricans have faced increased health threats from chronic diseases, particularly diabetes and hypertension. The patient-provider relationship is the main platform for individual disease management, whereas the community, as an agent of change for the community’s health status, has been limited in its support of individual health. Likewise, traditional research approaches within communities have placed academic researchers at the center of the process, considering their knowledge was of greater value than that of the community. In this paradigm, the academic researcher frequently owns and controls the research process. The primary aim is contributing to the scientific knowledge, but not necessarily to improve the community’s health status or empower communities for social change. In contrast, the community-based participatory research (CBPR) model brings community members and leaders together with researchers in a process that supports mutual learning and empowers the community to take a leadership role in its own health and well-being. This article describes the development of the community-campus partnership between the University of Puerto Rico School of Medicine and Piñones, a semi-rural community, and the resulting CBPR project: “Salud para Piñones”. This project represents a collaborative effort to understand and address the community’s health needs and health disparities based on the community’s participation as keystone of the process. This participatory approach represents a valuable ally in the development of long-term community-academy partnerships, thus providing opportunities to establish relevant and effective ways to translate evidence-based interventions into concrete actions that impact the individual and community’s wellbeing.

Keywords: Community-based participatory research, Community-campus partnership, Health disparities, Puerto Rico

The National Institutes of Health, in 1999, defined health disparities as the “differences in the incidence, prevalence, mortality, and burden of diseases and other adverse health conditions that exist among specific population groups in the United States” (1). These differences in health outcomes and their determinants between segments of the population are defined by social, demographic, environmental, and geographic characteristics (2). In other words, the context of individuals and communities determines health status; and represents an interplay between variables that can be controlled by the individual and those which cannot. Attempting to close health disparity gaps requires a depth of understanding of the context, processes, and drivers that support how these variables interact with each other (3, 4).

The challenge of how to change these adverse trends in health outcomes, and how to reduce the threats to health status and well-being, has been the subject of research and debate for over three decades (5). Many interventions, aimed to reduce the burden of these disparities at the individual and the community level, have been developed using traditional rigorous methodologies (6). Although these approaches have been successful in improving many clinical problems, the persistence of health disparities suggests that “traditional” research methodologies grounded in clinical research might not be appropriate or effective in some instances. More traditional designs usually fail to consider the multi-dimensional aspects of behavior, community dynamics and organization, and the impact of policy on health status. As a consequence, traditional researchers often do not clearly understand many of the social and economic complexities that motivate individuals’ and families’ behaviors. Conversely, community members, often weary of being “guinea pigs” in the research arena, increasingly demand that researchers address locally identified needs. After years of feeling ‘used and abandoned’ by researchers, community members often perceive that no direct benefit to the community comes from participating in the research process (7–9). As a result, community members might be reluctant to participate in research studies, leading to traditional researchers complaints about the challenges of recruiting “research subjects”.

Community-based participatory research

An approach to addressing this situation, and the associated health disparities, is to make the affected community or population a partner in the decision-making and research processes. This approach allows active participation of community members in the needs assessment, evaluation, design and implementation of selected interventions and programs. Proactively increasing community participation at the beginning of research activities results in a better understanding of the assets and strengths of the community as well as defining the social and environmental conditions that support health disparities.

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) is a recognized strategy to translate scientific knowledge into practical benefits to the community and is grounded in the philosophy of fully engaging communities as partners in the research process. In CBPR, researchers and community members work side by side to identify a problem, develop an appropriate research plan to address the issue and implement the research methodology. Once completed, research outcomes are presented to the community at large and, in partnership with researchers, the community devises a plan of action to address the problem. There are several definitions of CBPR but these eight key principles, developed by Israel and colleagues (10), summarize the fundamental concepts of this approach:

Recognizes community as a unit of identity.

Builds on strengths and resources within the community.

Facilitates collaborative partnerships in all phases of the research.

Integrates knowledge and action for mutual benefit of all partners.

Promotes a co-learning and empowering process that attends to social inequalities.

Involves a cyclical and iterative process.

Addresses health from both positive and ecological perspectives.

Disseminates findings and knowledge gained to all partners.

The purpose of CBPR is not simply to find answers to complex social questions but to use those results to provide information that can be used by the community to develop solutions to their problems. If the research design and methods actively engage community members in an equitable manner, trust and respect are likely to develop and be maintained (9–11).

Engaging in research activities with local communities, to understand and address complex health problems, requires the development of collaborative solutions. One approach includes the participation of communities, and academic research institutions, working together as equal partners, building on the assets, strengths, and capacities of one another. These alliances are often called community-academy partnerships, which have been effective in addressing issues critical to the community and producing significant outcomes for academia and the community. These partnerships have served to: 1) encouraging health professions education, (i.e., through service-learning); 2) enhance access to health care and improving health care delivery, (i.e., through health services provided); and 3) increase community willingness to participate in research, (i.e., through community-based participatory research). Finally, community-academic partnerships have been seen as an effective way to engage in long-term relationships aimed to develop and implement promising interventions to reduce health disparities in high- or at-risk communities (12–14).

In this paper, we present our experience in the development of a community-academic partnership between the University of Puerto Rico School of Medicine and the community of Torrecilla Alta, better known as Piñones. This low-income community, whose residents experience a high prevalence of chronic disease, limited access to health care services, and racial and social discrimination, opened its doors to this partnership. The goal was to promote the active participation of community members in the identification of the best solutions to their health care issues. We discuss the development of this community-academic partnership and the challenges and opportunities encountered in the process.

The partner community

Piñones is a high-risk community located in the Loíza municipality on the northeastern coast of Puerto Rico. This municipality is demographically unique in that its residents are predominantly black Hispanic descendants of the slave trade from Africa. Residents of this municipality have faced important challenges related to their health, security, and well-being. The criminal activity in the area has severe consequences for the population including the stigma, discrimination, and segregation associated with “violent neighborhoods”.

Piñones, is a sector of Loíza, detached from the rest of the municipality by three natural barriers: 1) a river that separates Piñones from the remainder of the municipality’s population (Río Grande de Loíza); 2) the largest mangrove forest that remains in Puerto Rico (15) surrounding its southern border; and 3) the Atlantic Ocean to the north. Because of its geographic location, Piñones remains relatively isolated with only one two-lane road that runs through the community along the coastline of the Atlantic Ocean. Public transportation is very limited.

In 2010, US Census data reported that 2,322 persons lived in Piñones. The community is mostly Hispanic (99%), young (median age, 27.5 years; 35.8% of the population are < 18 years of age), with low educational attainment (43.9% of residents > 25 years of age have a high school diploma or equivalent graduate degree), high poverty (69.8% living below the federal poverty level), and with high unemployment (30% of the population) (16).

The geographic separation of Piñones from Loíza has contributed to inadequate access to health care services. The nearest health care center is about 9 miles away from the community and is not easily accessible because of distance and the lack of adequate sidewalks or transportation. Besides their residents, Piñones has a large “transient” population consisting of tourists and local visitors, who primarily during the weekends, go to the beach and enjoy the traditional kiosks. These are local markets that sell frituras, traditional Caribbean fried turnovers and fritters filled with meat, crabmeat, or vegetables; beverages, and play music from the Caribbean. The kiosks constitute one of the major landmarks of this community. However, most of kiosks are owned by non-residents. As a result, the community receives little direct financial benefit from these businesses but directly receives the impact of traffic congestion and the social and environmental consequences of constant movement of people into and out of the area. On the other hand, the community history of solidarity in the defense of their rights and the familiarity among its residents, who usually have been living in this community for many years, are the foundation of the community’s resilency.

Community-academy partnership: “Salud para Piñones project”

Beginning of the research partnership

In late 2009, the community-based organization “Corporación Piñones se Integra” (COPI, for its acronym in Spanish) contacted the School of Medicine (SoM) at the University of Puerto Rico Medical Sciences Campus (UPR-MSC) to discuss community concerns about the weakening health status of the Piñones residents. This initial contact led to a series of meetings between community members and faculty members of the SoM’s Endowed Health Services Research Center (EHSRC) to discuss and outline strategies that could assist the community in improving the well-being of its residents. After several meetings with SoM-EHSRC faculty, a formal Steering Committee, called “Salud para Piñones” was established. Its initial objectives were to: 1) complete a community health needs assessment for a comprehensive socio-demographic and health description of the community, its prevalent diseases, and to identify formal and informal health care systems used by Piñones residents, and issues related to access to health care services; 2) further build and strengthen an effective and sustainable partnership between the SoM, and the community through the participatory action research model; and 3) define community priorities and establish a plan of action to address issues and challenges to Piñones health and well-being.

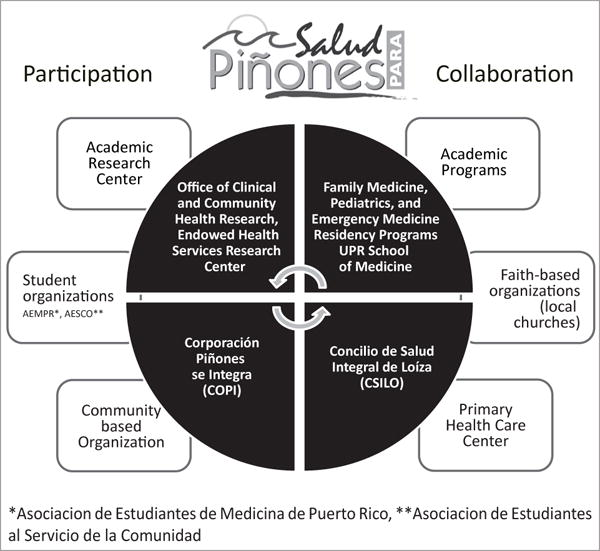

Given the community’s desires and community leadership in looking for solutions to their healthcare issues, participatory research (approved by UPR-MSC Institutional Review Board) was considered a suitable approach and a sound base on which to develop this initial community-campus partnership. Included in this team were a community-based organization (COPI), several community faith-based organizations, an academic research center (the Office of Clinical and Community Health Research of the EHSRC), organizations of medicine students, a community-based primary health care center (“Concilio de Salud Integral de Loíza”), and SoM academic training programs (Pediatrics and Family Medicine Residency Programs). The participants of this partnership are represented in Figure 1. We began with monthly meetings on Saturdays with more frequent encounters as needed.

Figure 1.

“Salud para Piñones” partnership participants and collaborators

As this partnership evolved, it was critical to consider the roles, expectations, and commitment of each member. The first partner to come to the relationship was COPI, one of a very limited number of community-based organizations within Piñones. In fact, it was COPI’s executive director who had made the initial contact with the SoM, voicing her concern for the health and well-being of the community. COPI’s mission, in its service to Piñones, is to: 1) improve the quality of life for community residents and visitors alike; 2) strengthen the community through various sustainable development initiatives while honoring the unique characteristics and needs of the community; and 3) promote community participation, empowerment, and mobilization through social improvement and micro-enterprise development (17). As a known and trusted member of the community, COPI served as intermediary to introduce researchers from the SoM-EHSRC to the community, offered their facilities for meetings, and participated directly with SoM-EHSRC researchers in community outreach efforts. A primary reason for this partnership beginning and why it has been successful rests in the fact that COPI is a ‘trusted broker’ within the community, serving to validate the interests and commitment of the SoM in the community’s long-term health and well-being.

The Office of Clinical and Community Health Research (OCCHR), of the SoM-EHSRC, is the primary academic research member of the partnership. Its mission supports the EHSRC’s activities to eliminate health disparities and improve the health and quality of life of individuals, families, and communities in Puerto Rico through the establishment of community partnerships, using participatory research strategies.

Unique but critical members of this community-academic partnership were the UPR-SoM medical students’ organizations and their participation. While evidence supports the effectiveness of CBPR in affecting social action for positive changes in community health status, CBPR research models and opportunities for participation are often woefully lacking in both the undergraduate and graduate medical education curricula. In 2008, the Association of American Medical Colleges established learning objectives in medical student education programs requiring that educational content meet evolving social needs of communities, practice patterns, and scientific developments in disease (18). However, the percentage of graduating medical students reporting participating in a community-based research project as part of an elective or volunteer activity during their undergraduate career remains relatively low.

Also, other essential partners in this initiative were the UPR-SoM Pediatrics and Family Medicine Residency Programs. Once physicians enter their residency training, experience with CBPR and community becomes more difficult even in programs that should be supportive of experiences with community engagement, such as Pediatrics or Family Practice. For CBPR to be successful, these theories and opportunities for application must be fully integrated into the medical academic culture, including faculty training to develop the skills and experience necessary to effectively conduct CBPR-grounded research. The inclusion of these residency programs was a unique opportunity for the active inclusion of CBPR in graduate medical education at the UPR-MSC.

The Concilio de Salud Integral de Loíza (CSILO) is the fourth member of this CBPR partnership. As a Federal Qualified Health Center which serves Piñones and the larger Loíza municipality, the clinic is both the community’s comprehensive primary health care provider but is also the training site for physicians in the Family Medicine residency program. Engagement of healthcare professionals from the CSILO, such as the nutritionist and the medical educator as members of the partnership, led to their active participation in community assessments as well as the joint development of community of interventions targeted to addressing specific concerns held by Piñones residents.

Last, but critical for the success of this partnership, were faith-based organizations. The active integration of leaders and members of local churches to this partnership allowed access to other community members and resources that became fundamental to the support of community activities.

The participation of partners with different points of view about the community’s health-related issues and their solutions, provided a unique opportunity to build liaisons between community groups that, even though living in the same community, had never worked together. The project “Salud para Piñones”, following a participatory approach, offered a space for open discussion and collaboration based on community strengths and resources.

Phase I: Building relationships and realizing the fruits of partnership

From the first contact from COPI to the UPR-MSC School of Medicine, approximately six months were invested in monthly visits from SoM and OCCHR to the community. In these visits, academic partners engaged with residents to listen to their concerns and learn about Piñones’ history, assets, and challenges. During this process, the group started working with community residents and leadership to determine the most appropriate first steps in determining the needs of the community and how to continue to strengthen the relationship between the community and the academy.

In spring 2010, following several meetings in and with the community, the partnership decided to undertake a comprehensive community assessment. Based on community input and led by investigators and community members from the Steering Committee, a two-phase mixed methods explanatory sequential design (19) was used for data collection and analysis. We performed a community-wide survey based on a representative sample of the population (127 participants, 69 in pediatric survey), in-depth interviews (five community leaders) and focus groups (28 participants). This first collaborative project allowed us to: 1) start planning a research project together; 2) obtain comprehensive information about the community health status; 3) explore in-depth the opinion of the residents, community leaders, and health providers regarding the health needs of the community; and 4) strengthen the partnership and build trust among partnership members.

Phase II: Engaging the larger community in the discussion and decision-making process

A core principle of CBPR is that results from community evaluation, such as the community needs assessment, be brought back to the community-at-large, not exclusively shared with select individuals (10). As data were available, a series of community meetings were held with the community members. Two meetings were held to present and discuss health assessment results on two Saturdays to assure that residents who wanted to attend a meeting would have the opportunity to do so. One meeting was held in COPI facilities (15 participants) and another at the Hospital UPR in Carolina (25 participants). Community members were invited by community leaders in churches and other locations throughout the community. Also, ministers and preachers at local churches were asked to participate in the meetings. Each meeting was structured in three parts: 1) a brief introduction of the project and the background of its development and purpose, 2) a PowerPoint presentation of the outcomes of the community needs assessment, and 3) a dedicated time for open discussion with residents. During this time, attendees were asked for their general thoughts on the outcomes of the needs assessment and if they felt or believed that the outcomes were like or unlike what they had thought about the health and wellness of Piñones. Attendees were also asked, based on the outcomes presented, what would they consider to be the top health-related problems facing Piñones today (present time) and what types of activities, programs, or interventions they thought would be effective in the community to improve Piñones’ health and wellness.

These community ‘talkback’ sessions have proven to be invaluable as ‘Salud para Piñones’ became more established in the fabric of the community, strengthening the threads of trust that had begun to develop. Residents began to see that they were respected by the academic researchers and that there were not only opportunities for them to engage in the community development/research process, they were actively invited to participate in the decision making process. For the academic members of the group, these discussion sessions deepened their understanding of the thoughts and concerns of the community beyond ‘what the data say’.

Once all meetings were completed, the core leadership of ‘Salud para Piñones’ met to review community feedback and reflect on the needs assessment outcomes. From these discussions, it was determined that four social and health needs were currently priority issues for the community: lack of emergency services within the community, lack of preventive services and health education, high prevalence of hypertension and diabetes in the adults, and high prevalence of asthma in children. Once these priority issues were identified, the group participated in a brain-storming session, generating a list of possible short and long-term interventions for each of these primary issues. There were several outcomes of this process: 1) the need for a comprehensive need assessment in the pediatric population, 2) the need for parallel research and service agendas to understand and supply community needs, 3) the need to identify and build resources at the local level such as community volunteers that could be trained to assist in the development of health-related interventions in the community, and 4) the commitment to support this initiative.

As result, the group identified community activities that could be implemented in a relatively short period of time, typically activities that would help continue to raise awareness within the community about ‘Salud para Piñones’, strengthen the trust and communication between the academy and the community, and provide the community with information and more immediate access to services. An example of these activities was the Piñones community-wide health clinic, attended by over 230 community members. This activity was organized primarily with the support of the medical students organization. It provided an opportunity for medical students to work with community members in the planning of an activity that not only allowed community members to receive free screenings, vaccinations and information on chronic diseases management and healthy lifestyles, but also was meaningful and relevant to the community’s ways of doing things. Another example was the school health clinics in which over 90 children received general preventive care interventions, coordinated with the UPR-SoM Pediatric Residency Program. Also, sponsored by the Susan G. Komen Foundation of Puerto Rico, breast cancer screenings were organized which brought a mobile mammography clinic to the community on two separate occasions, providing free mammograms to more than 80 women in Piñones and Loíza. A summary of the community engagement activities held as part of the services agenda of ‘Salud para Piñones’ partnership is found in Table 1. The organization of these activities also allowed the identification of new collaborators to support further initiatives of the partnership.

Table 1.

Summary of community engagement activities, “Salud para Piñones”

| Activity | Sponsors and Collaborators | Target population | Objectives | Participants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Piñones Community Health Clinic | UPR School of Medicine Faculty, AMSPR & AESCO and Community Churches | General population | To provide orientation and screening services to community members with emphasis activities for health promotion and disease prevention | 234 people |

| School-based Health Clinic | UPR SoM Pediatric Residency Program, AMSPR & AESCO | Students (K to 6) | To provide screening for BMI, dental evaluation, and visual acuity | 96 children |

| CPR and first aid certification to community volunteers from the Red Cross | UPR School of Medicine, Medical Sciences Campus | Community volunteers | To increase community capacity to respond to health related emergencies | 17 adults |

| Clinics of audiology and vision “Niños Consentidos” | Organized and sponsored by Ronald Mc Donald Foundation | Children (0 to 18 years) | To provide hearing and visual acuity evaluation to Piñones community children 0 to 18 years | 35 children |

| Breast Cancer Screening Clinics | Sponsored by Susan G. Komen Foundation | Women in the Piñones/Loíza community | To provide screening services for breast cancer to the Piñones Community | 86 women |

| Workshop “Cuidando a tu pareja” | Sponsored by Susan G. Komen Foundation | General population | To provide education to the community and caregivers about social support needs in breast cancer | 17 adults |

| School-based garden and healthy life-style activities | Multiple sponsors | School community | To develop a school garden and provide education about healthier lifestyles | 50 children |

| Community-based workshops: “Tomando control de su salud” and “Manejo personal de la diabetes” | Puerto Rico Department of Health & Puerto Rico Clinical & Translational Research Consortium | Persons with chronic diseases | To provide evidence based interventions for chronic disease self-management in the community | 41 adults |

| Community Health Workers Closing Community Forum | Multiple sponsors | General population | To educate the community about the community health workers role in the community and to provide screening and education about hypertension control | 32 adults |

| CPR and First Aid Workshop: “Family & Friends CPR Anytime” from the American Heart Association | Emergency Medicine Residency Program, Mr. José Maldonado, PAZOS FBO Services, Mr. Elvin Hernández Crespo, Mrs. Alicebelle Román Echevarría and JM Consulting Enterprises Inc. | Community Leaders | To increase community capacity to respond to health related emergencies | 11 adults |

| Health related emergencies in pediatric population | Pediatrics Residency Program, School of Medicine | School community | To increase capacity to respond to health related emergencies in pediatric population | 13 adults |

Phase III: Building on success, deepening trust

Our first year’s efforts in this participatory venture have not only enabled our community-academic partnership to complete essential needs assessments, but also provided a platform to explore the mutual value systems, clarify the assets and resources of the community and determine needed resources, including expanding the number of partners in our work.

As we strengthened our partnership with the community of Piñones, we completed our analysis of the initial community needs assessment and the child and family health needs assessments and established appropriate tracking processes for the various community activities and short-term interventions held in the community, allowing us to evaluate their impact on the community. Most importantly, the community-academy leadership group developed a participatory action plan for the research agenda targeting community priorities and needs. This action plan resulted in the following research activities, among others (Table 2):

During 2011–2012, a participatory research project was coordinated by “Salud para Piñones” to integrate the children in the 4th to 6th grades of the community’s elementary school in an intervention designed to increase knowledge, attitudes and practices in the consumption of fruits and vegetables. This initiative was supported by the UPR Pediatric Residency Program and several organizations which facilitated the development of a school garden as part of the intervention.

During 2012–2014, “Salud para Piñones” engaged in the development of an intervention using novel strategies, such as intervention mapping (20) and mixed methods analysis to evaluate the impact of integrating the community health worker model to adapted evidenced-based interventions aimed to improve chronic disease self-management in the community. This project received funding from the pilot project program of the Puerto Rico Clinical and Translational Research Consortium of the UPR-MSC and was developed in collaboration with the UPR Family Medicine Residency Program. The development of this pilot project provided an excellent opportunity to build local resources, through the training of community health workers who gained knowledge and skills to support other initiatives beyond this partnership. The results of these studies will be available in future publications.

Table 2.

Summary of community-based research activities, “Salud para Piñones”

| Research projects* | Study objectives |

|---|---|

| Building community campus partnerships for healthy communities: The Salud para Piñones Project | To develop and sustain a community-campus partnership development between the UPR-SoM and Piñones Community |

| Evaluation of community health needs through participatory research: Building bridges to address health disparities in Puerto Rico | To conduct a community health need assessment based on mixed methods to evaluate socio-demographic factors, prevalent diseases, risk factors, and health care utilization in the community |

| Assessment of pediatric health needs through participatory approach | To conduct a pediatric health need assessment using a participatory approach to evaluate health related needs in the pediatric community |

| Pilot Study: “Aprendiendo y cultivando”: an enhanced school-garden intervention to increase fruits and vegetables intake in a low income Hispanic community in Puerto Rico | To evaluate the role of school gardens in student knowledge and practices towards healthy foods and lifestyles using as model the “Gardens for Learning” initiative of the California Garden School Initiative. |

| Pilot Study: A multilevel intervention for chronic disease self-management in the community | To develop a culturally-tailored, multi-level intervention using Community Based Participatory Research principles to facilitate the integration of community health workers in the support chronic disease self-management in the community |

These studies were approved by the UPR School of Medicine Institutional Review Board

The implementation of these projects required the participation of partnership members in different roles. A continuous process of communication through monthly meetings allowed the sharing of the process and results from each component. The integration of community members in each step of the research process was fundamental to the completion of the projects. As the project advanced, the group explored different strategies to improve the dissemination of the results of to the community-at-large. One product of this exploration is the “Salud para Piñones Informa” newsletter (Figure 2) that is produced quarterly with updated information and distributed to the community.

Figure 2.

“Salud para Piñones Informa” newsletter

Challenges and opportunities

Increasing community participation is an exciting but challenging experience. The first encounters between community members and academic researchers are critical for the successful development of effective partnerships (21). Prior experiences of the community might facilitate or impede this process. In Puerto Rico, communities experiencing significant social and health disparities are common targets for the development of “research projects”. Often, these activities respond to course requirements or researcher-driven priorities with very limited integration of community members on the proposed topics or the process of the research. In many instances the community does not receive any information about the results or any direct benefit for their participation. Unfortunately, this situation was a common complaint found in the Piñones community. Working with these unfavorable experiences, or the perception of being used by academia, is a challenge frequently encounter in communities experiencing important health disparities (21, 22). To overcome this, since the beginning of the partnership, the Steering Committee established a commitment that all the information resulting from any research activity of the partnership will be shared with and available to community members. Community members valued this openness. The information sharing has occurred through local presentations, group discussions, and newsletters. Also, data collected is available for other community-driven initiatives. The Steering Committee revises the language if written information is to be shared, to make sure that the language is appropriate to the community. Also, community researchers are fully integrated into the dissemination of results, including as co-authors in abstracts, posters or manuscripts resulting from this collaboration. They also are active participants in the presentations of the study results. For example, they were invited to present, with the academic researchers, the results of a pilot study at the UPR-MSC 34th Annual Research and Education Forum which included oral and poster presentations.

Another important challenge for the group was how to strike a balance between research initiatives and the service needs of the community. The academy imposes a structure on researchers based on a set of expected outcomes, including publications and funding, that does not necessarily translate into community needs. However, to effectively receive support from the community and develop a long-term commitment, we needed to acknowledge and accommodate the different timelines and be flexible in negotiating the priorities of the initiatives. In this experience, developing parallel agendas for research and service through community outreach activities was a strategy that helped us, as academic researchers, increase community support and trust in the partnership. We were not just ‘doing research’ but building resources with the community to address health needs identified by the community. The development of outreach activities allowed us to learn and accompany the community in their ways of doing things and at the same time increased the exposure of the project to a broader group of community members. In the development of community-academy partnerships, academic researchers need to be flexible to validate community knowledge and support their preferences. Community researchers also need to be open to new ways of doing things. This is a challenge and a learning process that is continuous and evolves as the partnership matures. On the other hand, this approach also increases time and resource burdens, demanding extra efforts for the planning of the outreach activities and identification of additional resources. Within the context of limited time and resources, this might result in a dilution of the time committed to other parts of the research process, such as data analysis and manuscript preparation. Achieving that balance is still part of our learning process.

As the partnership matures, we are challenged with how to sustain it as a long-term initiative, in our case, appropriated by the UPR-SoM and by the Piñones community. The development of community-campus partnerships requires time and commitment of both academia and the community. The partnership needs to move as the community moves. We have experienced changes in leadership, changes in the organizations that were supporting the project, and changes in the academic partners. However, the constant presence of “Salud para Piñones” in the community has facilitated the process of engaging in new relationships with other stakeholders and resources to further community-based research activities.

Maintaining the enthusiasm of the community is also challenging. The competition with “new projects” or ideas from governmental agencies or community organizations might distract the partners from the long-term objectives of the collaboration. At the same time, new academic requirements or appointments reduce the time required from the academic partners to support the continuation of a long-term collaboration.

Funding is a big limitation. Unfortunately, the lack of understanding of the value of these initiatives by many funding organizations limits access and competitiveness of these partnerships while contending with more traditional research initiatives. However, there is an urgent need to facilitate the translation of scientific knowledge to the end-users. There is a growing recognition of the significance and health policy implications of these community-academy partnerships (12). We need to be creative and challenge traditional paradigms as more opportunities become available through federal agencies and foundations for community-engaged research. In our experience, funding is still a challenge, but we have found valuable resources in the community (i.e., volunteers and religious leaders) and academia (i.e., medical students, residents and committed faculty). There are increasing opportunities for the development of scientifically rigorous research and in-service learning experiences while providing services needed in the community. Some activities might be carried out with donations and community support, but institutional or external funding is required while the process transfers to the community and auto-sustainability occurs.

In our case, the “Salud para Piñones” collaborative project gave us the opportunity to better understand the needs and experiences with health services confronted by our communities. In addition, especially for graduate students and new investigators, this project represented a unique opportunity to reflect on the reality of our communities, translate the theory into practice, appreciate more the importance of community-based research, and being witnesses and key participants of the gradual transformation of the community and its residents.

Final thoughts

In Puerto Rico, there are many at-risk communities such as Piñones. Traditionally, academic researchers have worked ‘in’ communities to identify needs and implement programs to solicit change. Nevertheless, seldom do researchers work ‘with’ communities in true partnerships, as defined by community-based participatory research approach. Evidence indicates that CBPR has the potential to effect long-term change within communities. However, its implementation requires that academic researchers understand its principles and choose to invest the needed time and effort in building trust, communication, and commitment to communities experiencing health disparities. In the training of our future health care providers, it is important to promote experiences to work collaboratively with communities in need as they often serve as local agents of change in population health and well-being. The community-academy partnership between the community of Piñones and the UPR School of Medicine has resulted in the integration of research, outreach and service activities developed for mutual benefit for the community and the UPR-SoM. With this framework in place, the ‘Salud para Piñones’ community-academic partnership is positioned to expand its work in the community, engage in new research endeavors, and provide challenging opportunities to our faculty, residents, and medical students with interest in community-based research.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported partially by the Puerto Rico Clinical and Translational Research Consortium, Grant 8U545MD007587-03, the UPR School of Medicine Endowed Health Services Research Center, Grants 5S21MD000242 and 5S21MD000138 from the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NCMHD), National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Community Access to Child Health Program (CATCH) of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and the Piñones community and leaders. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the AAP, NCMHD or NIH.

Footnotes

The author/s has/have no conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.National Institutes of Health (NIH) [Internet] NIH health disparities strategic plan and budget, fiscal years 2009–2013. [cited date 2016 January 25] Available from: Url: http://www.nimhd.nih.gov.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Rationale for regular reporting on health disparities and inequalities. MMWR. 2011;60:3–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kilbourne A, Switzer G, Hyman K, Crowley-Matoka M, Fine M. Advancing health disparities research within the health care system: A conceptual framework. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:2113–2121. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.077628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brondolo E. Racial and ethnic disparities in health. Psychosom Med. 2015;77:2–5. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vanderbilt A, Dail M, Jaberi P. Reducing health disparities in underserved communities via interprofessional collaboration across health care professions. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2015;8:205–208. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S74129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whitehead T. Traditional approaches to the evaluation of community-based interventions: Strengths and limitations [Online series] University of Maryland; 2012. [cited 2016 January 25]. Available from: Url: http://www.cusag.umd.edu. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hartwig K, Calleson D, Williams M. The examining community-institutional partnerships for prevention research group. Developing and sustaining community-based participatory research partnerships: A skill-building curriculum. Washington: 2006. Community-based participatory research: Getting grounded [Online course] [cited 2016 January 25]. Available from: Url: www.cbprcurriculum.info. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Connors K, Seifer S, editors. Partnership perspectives. 1st. San Francisco, CA: Community-Campus Partnerships for Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Minkler M. Community-based research partnerships: Challenges and opportunities. J Urban Health. 2005;82(Suppl 2):ii3–ii12. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Israel B, Schulz A, Parker E, Becker A. Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Israel B, Eng E, Schulz A, Parker E. Methods in community-based participatory research for health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Israel B, Krieger J, Vlahov D, et al. Challenges and facilitating factors in sustaining community-based participatory research partnerships: Lessons learned from the Detroit, New York City and Seattle urban research centers. J Urban Health. 2006;83:1022–1040. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9110-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carney J, Maltby H, Mackin K, Maksym M. Community-academic partnerships: How can communities benefit? Am J Prev Med. 2011;41:S206–S213. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolff M, Maurana C. Building effective community-academic partnerships to improve health. Acad Med. 2001;76:166–172. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200102000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parés D. Restoration of mangrove tidal channels in the Piñones State Forest & Natural Preserve, 2008 [Internet] [cited 2010 March 3]. Available from: Url: http://www.gulfmex.org/crp/3002C.html.

- 16.U.S Census Bureau [Internet] Summary File 1. 2010 [cited 2016 January 26]. Available from: http://www.census.gov.

- 17.Corporación Piñones se Integra [Internet] [cited 2015 May 15]. Available from: Url: http://www.copipr.com/index.html.

- 18.Association of American Medical Colleges. Learn, serve and lead. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Creswell J, Plano V. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bartholomew L, Parcel G, Kok G, Gottlieb N, Fernández M. Planning health promotion programs: An intervention mapping approach. 3rd. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fallon L, Frederick L, Tyson A. Successful models of community-based participatory research. 1st. Washington DC: National Institute of Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davis R, Cook D, Cohen L. A community resilience approach to reducing ethnic and racial disparities in health. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:2168–2173. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.050146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]