Synopsis

Cancer treatments usually have side effects of bone marrow depression, mucositis, hair loss, and gastrointestinal issues. Rarely do we think of skin side effects until patients have been treated successfully with EGFRi as they commonly experienced skin reactions. Those skin reactions include papulopustular rash, hair changes, radiation dermatitis enhancement, pruritus, mucositis, xerosis, fissures, and paronychia. This paper discusses the common skin reactions seen when using EGFRi. This paper presents an overview of skin as the largest and important organ of the body including an overview of skin assessment, pathophysiology of the skin reactions, nursing care involved and introduction to the emerging cancer nursing specialty of oncodermatology.

Keywords: Skin Reactions, EGFRi (epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors), Oncodermatology

Introduction

Over the past decade, it has become important to incorporate dermatology into cancer care since skin reactions are one of the major reactions to newer anti-cancer therapies like epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors (EGFRi). Over expression of EGFR is strongly associated with the development of and progression in a number of cancers (Lacouture, et al 2011; Wilkes & Barton-Burke, 2016). Agents that inhibit the EGFR pathway are: 1) monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) such as cetuximab and panitumumab, and 2) small molecule inhibitors: erlotinib, gefitinib, afatinib, lapatinib (Eilers et al, 2009). Patients treated with EGFRi commonly experience dermatologic side effects including papulopustular rash, hair changes, radiation dermatitis enhancement, pruritus, mucositis, xerosis, fissures, and paronychia (Lacouture, et al, 2011). These are important side effects related to new cancer treatments. This paper presents the common skin reactions seen with EGFRi, and presents an overview of skin assessment, pathophysiology, and nursing care. These side effects should be recognized early, diagnosed promptly, and treated before they affect a patient’s quality of life and mortality. This paper also provides an introduction to the emerging cancer nursing specialty of oncodermatology.

Patient Assessment

Nurses play a key role in assessing, preventing and managing patients with cancer treatment-related skin conditions. Understanding factors that comprise wound healing should be incorporated into nursing assessment and can be found in Table 1. Table 2 outlines criteria for a basic skin assessment and common terminology to describe skin changes. When performing a skin assessment nurses must inspect and palpate the skin noting color, moisture texture, morphology, and distribution. Utilizing a grading system like the CTCAEv.4 found in Table 3 provides a consistent and standard way to assess and document skin and subcutaneous disorders.

Table 1.

Patient/Treatment-Related Factors That Compromise Wound Healing

| Patient- Related Factors | Treatment -Related Factors |

|---|---|

| Age | Medication |

| Compromised nutritional status | Medical treatments |

| Body type (extremes: obese vs. extremely thin) | |

| Low performance status | |

| Location/Site of injury | |

| Previous sun/radiation exposure | |

| Smoking | |

| Comorbidities (cardiovascular, pulmonary, renal, & liver disease, lymphedema, autoimmune disorders, diabetes) | |

| Psychological distress |

Data from Principles of skin care and the oncology patient (2010). In Haas M. L. &. M.,G.J. (Ed.), . Pittsburgh,Pa: Oncology Nursing Society.

Table 2.

Dermatologic Assessment/History

Skin assessment/history

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Review medications including over the counter and complementary/alternative therapies |

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Past medical and surgical history including co morbidities, treatment and nutritional status |

|

||||||||||||||||||

Data from Bickley, L.S. & Szilagyi, P.G. (2013) and “Skin Assessment,” by L. Johannsen, 2005, Dermatology Nursing, 17(2), p.166. Copyright 2005 by Jannetti Publications, Inc. Reprinted with permission. Need permission

Table 3.

CTCAE V.4 Grading Scale – source: NIH; no permission necessary

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade | |||||

| Adverse Event | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Alopecia | Hair loss of <50% of normal for that individual that is not obvious from a distance but only on close inspection; a different hair style may be required to cover the hair loss but it does not require a wig or hair piece to camouflage | Hair loss of >=50% normal for that individual that is readily apparent to others; a wig or hair piece is necessary if the patient desires to completely camouflage the hair loss; associated with psychosocial impact | - | - | - |

| Definition: A disorder characterized by a decrease in density of hair compared to normal for a given individual at a given age and body location. | |||||

| Body odor | Mild odor; physician intervention not indicated; self care interventions | Pronounced odor; psychosocial impact; patient seeks medical intervention | - | - | - |

| Definition: A disorder characterized by an abnormal body smell resulting from the growth of bacteria on the body. | |||||

| Bullous dermatitis | Asymptomatic; blisters covering <10% BSA | Blisters covering 10–30% BSA; painful blisters; limiting instrumental ADL | Blisters covering >30% BSA; limiting self care ADL | Blisters covering >30% BSA; associated with fluid or electrolyte abnormalities; ICU care or burn unit indicated | Death |

| Definition: A disorder characterized by inflammation of the skin characterized by the presence of bullae which are filled with fluid. | |||||

| Dry skin | Covering <10% BSA and no associated erythema or pruritus | Covering 10–30% BSA and associated with erythema or pruritus; limiting instrumental ADL | Covering >30% BSA and associated with pruritus; limiting self care ADL | - | - |

| Definition: A disorder characterized by flaky and dull skin; the pores are generally fine, the texture is a papery thin texture. | |||||

| Erythema multiforme | Target lesions covering < 10% BSA and not associated with skin tenderness | Target lesions covering 10–30% BSA and associated with skin tenderness | Target lesions covering >30% BSA and associated with oral or genital erosions | Target lesions covering >30% BSA; associated with fluid or electrolyte abnormalities; ICU care or burn until indicated | Death |

| Definition: A disorder characterized by target lesions (a pink-red ring around a pale center). | |||||

| Erythroderma | - | Erythema covering >90% BSA without associated symptoms; limiting instrumental ADL | Erythema covering >90% BSA with associated symptoms (e.g., pruritus or tenderness); limiting self care ADL | Erythema covering >90% BSA with associated fluid or electrolyte abnormalities; ICU care or burn until indicated | Death |

| Definition: A disorder characterized by generalized inflammatory erythema and exfoliation. The inflammatory process involves >90% of the body surface area. | |||||

| Fat atrophy | Covering <10% BSA and asymptomatic | Covering 10–30% and associated with erythema or tenderness; limiting instrumental ADL | Covering >30% BSA; associated with erythema or tenderness; limiting self-care ADL | - | - |

| Definition: A disorder characterized by shrinking of adipose tissue. | |||||

| Pain of skin | Mild pain | Moderate pain; limiting instrumental ADL | Severe pain; limiting self care ADL | - | - |

| Definition: A disorder characterized by marked discomfort sensation in the skin. | |||||

| Periorbital edema | Soft or non-pitting | Indurated or pitting edema; topical intervention indicated | Edema associated with visual disturbance; increased intraocular pressure; glaucoma or retinal hemorrhage; optic neuritis; diuretics indicated; operative intervention indicated | - | - |

| Definition: A disorder characterized by swelling due to an excessive accumulation of fluid around the orbits of the face. | |||||

| Photosensitivity | Painless erythema and erythema covering <10% BSA | Tender erythema covering 10–30% BSA | Erythema covering >30% BSA and erythema with blistering; photosensitivity; oral corticosteroid therapy indicated; pain control indicated (e.g., narcotics or NSAIDs) | Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated | Death |

| Definition: A disorder characterized by an increase in sensitivity of the skin to light. | |||||

| Pruritus | Mild or localized; topical intervention indicated | Intense or widespread; intermittent; skin changes from scratching (e.g., edema, papulation, excoriations, lichenification, oozing/crusts); oral intervention indicated; limiting instrumental ADL | Intense or widespread; constant; limiting self care ADL or sleep; oral corticosteroid or immunosuppressive therapy indicated | - | - |

| Definition: A disorder characterized by an intense itching sensation. | |||||

| Purpura | Combined area of lesions covering <10% BSA | Combined area of lesions covering 10–30% BSA; bleeding with trauma | Combined area of lesions covering >30% BSA; spontaneous bleeding | - | - |

| Definition: A disorder characterized by hemorrhagic areas of the skin and mucous membrane. Newer lesions appear reddish in color. Older lesions are usually a darker purple color and eventually become a brownish-yellow color. | |||||

| Rash acneiform | Papules and/or pustules covering <10% BSA, which may or may not be associated with symptoms of pruritus or tenderness | Papules and/or pustules covering 10–30% BSA, which may or may not be associated with symptoms of pruritus or tenderness; associated with psychosocial impact; limiting instrumental ADL | Papules and/or pustules covering >30% BSA, which may or may not be associated with symptoms of pruritus or tenderness; limiting self care ADL; associated with local superinfection with oral antibiotics indicated | Papules and/or pustules covering any % BSA, which may or may not be associated with symptoms of pruritus or tenderness and are associated with extensive superinfection with IV antibiotics indicated; life-threatening consequences | Death |

| Definition: A disorder characterized by an eruption of papules and pustules, typically appearing in face, scalp, upper chest and back. | |||||

| Rash maculo-papular | Macules/papules covering <10% BSA with or without symptoms (e.g., pruritus, burning, tightness) | Macules/papules covering 10–30% BSA with or without symptoms (e.g., pruritus, burning, tightness); limiting instrumental ADL | Macules/papules covering >30% with or without associated symptoms; limiting self care ADL | - | - |

| Definition: A disorder characterized by the presence of macules (flat) and papules (elevated). Also known as morbilliform rash, it is one of the most common cutaneous adverse events, frequently affecting the upper trunk, spreading centripetally and associated with pruritus. | |||||

| Scalp pain | Mild pain | Moderate pain; limiting instrumental ADL | Severe pain; limiting self care ADL | - | - |

| Definition: A disorder characterized by marked discomfort sensation in the skin covering the top and the back of the head. | |||||

| Skin atrophy | Covering <110% BSA; associated with telangiectasias or changes in skin color | Covering 10–30% BSA; associated with striae or adnexal structure loss | Covering >30% BSA; associated with ulceration | - | - |

| Definition: A disorder characterized by the degeneration and thinning of the epidermis and dermis. | |||||

| Skin hyperpigmentation | Hyperpigmentation covering <10% BSA; no psychosocial impact | Hyperpigmentation covering >10% BSA; associated psychosocial impact | - | - | - |

| Definition: A disorder characterized by darkening of the skin due to excessive melanin deposition. | |||||

| Skin hypopigmentation | Hypopigmentation or depigmentation covering <10% BSA; no psychosocial impact | Hyperpigmentation or depigmentation covering >10% BSA; associated psychosocial impact | - | - | - |

| Definition: A disorder characterized by loss of skin pigment. | |||||

| Skin induration | Mild induration, able to move skin parallel to plane (sliding) and perpendicular to skin (pinching up) | Moderate induration, able to slide skin, unable to pinch skin; limiting instrumental ADL | Severe induration, unable to slide or pinch skin; limiting joint movement or orifice (e.g., mouth, anus); limiting self care ADL | Generalized; associated with signs or symptoms of impaired breathing or feeding | Death |

| A disorder characterized by an area of hardness in the skin. | |||||

| Skin ulceration | Combined area of ulcers <1 cm; nonblanchable erythema of intact skin with associated warmth or edema | Combined area of ulcers 1–2 cm; partial thickness skin loss involving skin or subcutaneous fat | Combined area of ulcers >2 cm; full-thickness skin loss involving damage to or necrosis of subcutaneous tissue that may extend down to fascia | Any size ulcer with extensive destruction, tissue necrosis, or damage to muscle, bone, or supporting structures with or without full thickness skin loss | Death |

| Definition: A disorder characterized by circumscribed, inflammatory and necrotic erosive lesion on the skin. | |||||

| Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) | - | - | Skin sloughing covering <10% BSA with associated signs (e.g., erythema, purpura, epidermal detachment and mucous membrane detachment) | Skin sloughing covering 10–30% BSA with associated signs (e.g., erythema, purpura, epidermal detachment and mucous membrane detachment) | Death |

| Definition: A disorder characterized by less than 10% total body skin area separation of dermis. The syndrome is thought to be a hypersensitivity complex affecting the skin and the mucous membranes. | |||||

| Telangiectasia | Telangiectasias covering <10% BSA | Telangiectasias covering >10% BSA; associated with psychosocial impact | - | - | - |

| Definition: A disorder characterized by local dilatation of small vessels resulting in red discoloration of the skin or mucous membranes. | |||||

| Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) | - | - | - | Skin sloughing covering ≥30% BSA with associated symptoms (e.g., erythema, purpura, or epidermal detachment) | Death |

| Definition: A disorder characterized by greater than 30% total body skin area separation of dermis. The syndrome is thought to be a hypersensitivity complex affecting the skin and the mucous membranes. | |||||

| Urticaria | Urticarial lesions covering <10% BSA; topical intervention indicated | Urticarial lesions covering 10–30% BSA; oral intervention indicated | Urticarial lesions covering >30% BSA; IV intervention indicated | - | - |

| Definition: A disorder characterized by an itchy skin eruption characterized by wheals with pale interiors and well-defined red margins. | |||||

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders – Other, specify | Asymptomatic or mild symptoms; clinical or diagnostic observations only; intervention not indicated | Moderate; minimal, local or noninvasive intervention indicated; limiting age-appropriate instrumental ADL | Severe or medically significant but not immediately life-threatening; hospitalization or prolongation of existing hospitalization indicated; disabling; limiting self care ADL | Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated | Death |

Performing a comprehensive skin assessment and history includes assessment for patient and treatment-related factors (see Table 1). A detailed history from either the patient or caregiver includes questions about the onset of rash (date), initial presentation, and progression of eruptions, alleviating and persisting factors, treatment history and outcomes with along with a review of systems (The Skin Physical Examination accessed 2016).

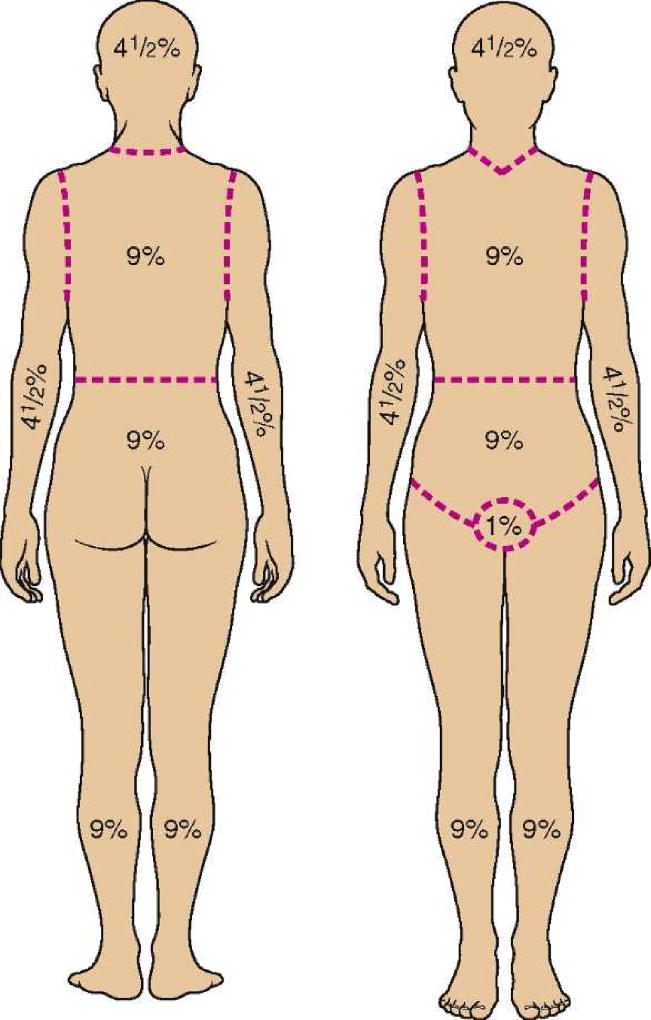

The nurse needs to specify the affected area and can consider calculating body surface area (BSA) using the Rule of Nines in Figure 1. Obtaining a past medical, surgical and social history is important paying attention to past dermatologic conditions (ie., Herpes simplex virus, contact dermatitis) or allergies to medications. Reviewing a medication list including prescriptions (topical, oral, subcutaneous) and over-the-counter medications including complementary or alternative therapies is essential. The assessment should include dates of changes in prescription drugs and dosage, if indicated.

Figure 1. Rule of Nines.

From Buck, C. (2011). Next Step: Advanced Medical Coding 2012 Edition Textbook and Workbook Package. Philadelphia, PA: W. B. Saunders. pp 223–276.

Pathophysiology and Clinical Presentation

Epidermal growth factor receptors are primarily expressed in basal keratinocytes, the outer layers of hair follicles, eccrine sweat and pilosebaceous glands and periungual tissues. Inhibiting EGF pathways in the skin results in arresting cell growth and migration, apoptosis, chemokine expression, and abnormal maturation and differentiation. The cellular cascade results in an inflammatory response with dermatologic manifestations such as acneiform rashes, xerosis, pruritus, periungual inflammation, and hair and nail plate disturbance.

Acneiform rashes occurs in up to 90% of patients on EGFRi. Rashes typically appear on the scalp, face, and upper body in sun exposed areas within the first 2 weeks of starting therapy, peaking at 4 weeks (Boone et al, 2007). The rash steadily declines at six to eight weeks (Lacouture et al, 2011). The rash first appears as erythema with a burning sensation as a result of an inflammatory cell release, vascular dilation, and increased permeability progressing to papules and pustules. The crusting of lesions occurs due to neutrophilic and keratinocyte debris, fibrin, and serum indicating a non-infectious etiology (Lacouture, 2006). A prevalence of dermatologic infections has been reported in patients on EGFRi who are leukopenic (Eilers et al, 2009). It is important to note that acneiform rashes are confused with acne vulgaris but both are pathologically different from one another.

Severe rashes are frequent with mAbs, such as cetuximab and panitumumab than TKIs (Wilkes & Barton-Burke, 2016). Yet EGFRi-induced rash has been reported to be an indication of treatment efficacy in some patients (Wacher et al, 2007).However, patients who underwent radiation therapy prior to starting EGFRi did not develop a rash during erlotinib therapy. But patients receiving EGFRi concomitantly with radiation are reported to have a higher incidence of high-grade radiation dermatitis (Lacouture et al, 2011).

Xerosis is reported in up to 46.5% of patients receiving EGFRi within the first month of therapy and can be attributed to transepidermal water loss due to abnormal keratinocyte differentiation (Valentine et al, 2014). Pruritus often occurs concomitantly with xerosis following EGFRi administration with the highest incidence rate seen in cetuximab followed by erlotinib (Fischer et al, 2013). Paronychia occurs after 2 to 3 months of therapy. It is typically a sterile process but can become superinfected. Nail matrix inflammation occurs as a secondary process. Non-scarring alopecia can occur after 2 to 3 months of therapy initially presenting as patchy hair loss progressing into diffuse hair loss. This type of alopecia generally resolves after discontinuation of therapy (Lacouture et al, 2011). The phases of skin changes and the pathophysiology are described in Table 4

Table 4.

Pathophysiology

| Phase | Cellular Level Changes | Body Response | Goal of Treatment | Patient Information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase I: weeks 0–1, erythema and edema like a sunburn. The patient feels a sunburn-like reaction (erythema, tenderness, slight swelling) on the face and areas that have previously been exposed to the sun. | EGFR inhibition in skin stops underlying keratinocytes from differentiating and migrating to skin surface to replace them, and they are arrested. | The body senses that these arrested replacement cells should not be there and thus causes them to undergo apoptosis or programmed cell death. The dead keratinocytes cause the release of chemokines, which recruit neutrophils to the area as part of the sterile, inflammatory response. | The goal is to preserve skin integrity, minimize discomfort, and prevent infection. | Key patient teaching includes (1) use skin cream with emollients to keep the skin from drying out; (2) avoid sun exposure, using a sunblock of SPF 30 or higher and protect skin with hat and clothes when out in the sun; (3) use a mild soap with active ingredients that reduce skin drying, such as pyrithione zinc (Head & Shoulders); (4) apply prescribed prophylactic skin creams; (5) report distressing tenderness, as pramoxine (lidocaine topical anesthetic) may help; (6) keep fingernails clean and trimmed. |

| Phase II: weeks 1–3, papulopustules appear The rash begins within 7–10 days of starting therapy and peaks in intensity in 2–3 weeks and then gradually gets better. | This sterile inflammatory process results in death of the keratinocytes (apoptosis) and the formation of debris, which causes a popular rash on the skin. | At the same time, the skin is no longer fortified by healthy keratinocytes, and thus, it thins and is unable to preserve water in the body, leading to skin dryness (xerosis) and itching. | The goal is to prevent infection, promote healing, and maximize comfort and coping during this time. See drug package inserts for specific information on holding or discontinuing drug for severe dermatologic adverse effects. | |

| Phase III: weeks 3–5, lesions crust | The skin becomes drier (xerosis) with pruritus and the formation of telangiectasias (dilated capillaries in the skin). | The skin flakes and itches. | For flaking skin, keratolytics such as lactic acid, salicylic acid, or urea-containing topicals such as 12% Lac-Hydrin or other exfoliating lotions can be helpful | |

| Phase IV: weeks 5–8, persistent dry skin, erythema, other skin/hair changes. | EGFR blockade of the hair follicles and nail beds results in hair changes (hair thinning or alopecia on scalp but increased hair growth on the eyelids (trichomegaly) or face (hypertrichosis). | The hair texture can change (changes in texture and strength). Paronychia (periungual inflammation) can develop with crusted lesions on nail folds and tenderness. Painful skin fissures on the fingers can develop. | It is important to assess eyelashes, and if they are long, they can fold back and irritate the conjunctiva; refer to an ophthalmologist for redirection as needed (Borkar et al., 2013). |

Source: Lacouture, et al

Clinical Practice Guidelines

Despite the fact that most patients receiving EGFRi experience skin toxicities, there is a dearth of controlled studies, lacking strong Level I evidence. In 2010, Lacouture and colleagues studied whether pre-emptive therapy could decrease the severity of panitumumab-related rash. They found that grade 2 or higher rash and other skin changes were significantly reduced in patients who received daily moisturizer, sunscreen, topical hydrocortisone, and oral doxycycline for 6 weeks compared to a control group. Also, patients in the pre-emptive group reported less quality of life impairment than the control group. However, in 2016, Melosky et al. conducted a prospective randomized study using prophylactic skin treatment for the prevention of erlotinib-induced skin rash. Patients receiving minocycline either prophylactically or reactively (after rash developed based on grade) were compared to those receiving no treatment unless there was severe, Grade 3, rash (Melosky et al. (2016). This study revealed a rash incidence of 84% but found no statistical difference between study arms. These two studies underscore the need for further research in this patient population.

Given the lack of evidence in the literature and the need for large-scale studies to define the best supportive care, there are a few clinical practice guidelines available for use with this patient population. The Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC, 2011) and the Alberta Health Services (2012) developed clinical practice guidelines for patients being treated with EGFRi. Both guidelines recommend that patients should receive individualized skin care management thus permitting the patient to receive maximum recommended EGFRi dose. The MASCC Skin Toxicity Guidelines can be found in Table 5. The guideline recommends prophylactic treatment in weeks 1 through 6 and week 8 when a patient begins EGFRi therapy (Lacouture et al., 2011).

Table 5.

MASCC Grading Tool for Skin Toxicities

| Adverse Event | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Papulopustular eruption (Grading individually for face, scalp, chest or back) | 1A. Papules or pustules <5; OR 1 area of erythema or edema <1 cm in size | 2A. Papules or pustules 6–20; OR 2–5 areas of erythema or edema <1 cm in size | 3A. Papules or pustules >20; OR more than 5 areas of erythema or edema <1cm in size | - |

| 1B. Papules or pustules <5; OR 1 area of erythema or edema <1cm in size AND pain or pruritus | 2B. Papules or pustules 6–20; OR 2–5 areas of erythema or edema <1cm in size AND pain, pruritus, or effect on emotions or functioning | 3B. Papules or pustules >20; OR more than 5 areas of erythema or edema <1cm in size; AND pain, pruritus, or effect on emotions or functioning | - | |

| Nail changes -Nail Plate | Onycholysis or ridging without pain | Onycholysis with mild/moderate pain; any nail plate lesion interfering with instrumental ADL | Nail plate changes interfering with self-care ADL | - |

| Nail changes -Nail fold | Disruption or absence of cuticle; OR erythema | Erythematous/tender/painful; OR pyogenic granuloma; OR crusted lesions; OR any fold lesion interfering with instrumental AD | Periungual abscess: OR fold changes interfering with self-care ADL | - |

| Nail changes -Digit tip | Xerosis AND/OR erythema without pain | Xerosis AND/OR erythema with mild/moderate pain or stinging; OR fingertip fissures; OR any digit tip lesion interfering with instrumental ADL | Digit tip lesions interfering with self-care ADL | - |

| Erythema | Painless erythema, blanching; erythema covering <10% BSA | Painful erythema, blanching; erythema covering 10–30% BSA | Painful erythema, nonblanching; erythema covering >30% BSA | - |

| Pruritus | Mild OR localized, intermittent, not requiring therapy | 2A. Moderate localized OR widespread intermittent AND requiring intervention | Severe, widespread constant AND interfering with sleep | - |

| 2B. Moderate localized OR widespread constant AND requiring intervention | ||||

| Xerosis | Scaling/flaking covering <10% BSA NO erythema/pruritus/effect on emotions or functioning | 2A. Scaling/flaking covering 10–30% BSA + pruritus OR effect on emotions/functioning | 3A. Scaling/flaking covering >30% BSA AND pruritus AND erythema AND effect on emotions/functioning AND + fissuring/cracking | - |

| 2B. Scaling/flaking + pruritus covering 10–30% BSA AND effect on emotions/functioning + erythema | 3B. Scaling/flaking covering >30% BSA And pruritus AND erythema AND effect on emotions/functioning AND fissuring/cracking + signs of super infection | - | ||

| Hair changes: scalp hair loss or alopecia | Terminal hair loss <50% of normal for that individual that may or may not be noticeable to others but is associated with increased shedding and overall feeling of less volume. May require different hair style to cover but does not require hairpiece to camouflage | 2A. Hair loss associated with marked increase shedding and 50–74% loss compared to normal for that individual. Hair loss is apparent to others, may be difficult to camouflage with change in hair style and may require hairpiece | - | - |

| 2B. Marked loss of at least 75% hair compared to normal for that individual with inability to camouflage except with a full wig OR new cicatricial hair loss documented by biopsy that covers at least 5% scalp surface area. May impact on functioning in social, personal or professional situations | ||||

| Hair changes: disruption of normal hair growth (specify) – Facial hair (diffuse, not just in male beard/mustache areas), Eyelashes, Eyebrows, Body hair, Beard and mustache hair (hirsutism) | Some distortion of hair growth but does not cause symptoms or require intervention | 2A. Distortion of hair growth in many hairs in a given area that cause discomfort or symptoms that may require individual hairs to be removed | - | - |

| 2B. Distortion of hair growth of most hairs in a given area with symptoms or resultant problems requiring removal of multiple hairs | ||||

| Hair changes: increased hair growth (specify) – Facial hair (diffuse, not just in male beard/mustache areas), Eyelashes, Eyebrows, Body hair, Beard and moustache hair (hirsutism) | Increase in length thickness and/or density of hair that the patient is able to camouflage by periodic shaving, bleaching or removal of individual hairs | 2A. Increase in length, thickness and/or density of hairs that is very noticeable and requires regular shaving or removal of hairs in order to camouflage. May cause mild symptoms related to hair overgrowth | - | - |

| 2B. Marked increase in hair density thickness and/or length of hair that requires either frequent shaving or destruction of the hair to camouflage. May cause symptoms related to hair overgrowth. Without hair removal, inability to function normally in social, personal or professional situations | ||||

| Flushing | 1A. Face OR chest, asymptomatic, transient | 2A. Symptomatic on face, or chest, transient | 3A. Face and chest, transient, symptomatic | - |

| 1B. Any location, asymptomatic, permanent | 2B. Symptomatic on face, or chest permanent | 3B. Face and chest, permanent, symptomatic | ||

| Telangiectasia | One area (<1cm diameter) NOT affecting emotions or functioning | 2A. 2–5 (1cm diameter) areas NOT affecting emotions or functioning | More than 6 (1cm diameter) OR confluent areas affecting emotions or functioning | - |

| 2B. 2–5 (1cm diameter) areas affecting emotions or functioning | ||||

| Hyperpigmentati on | One area (<1cm diameter) NOT affecting emotions or functioning | 2A. 2–5 (1cm diameter) areas NOT affecting emotions or functioning | More than 6 (1cm diameter) OR confluent areas affecting emotions or functioning | - |

| 2B. 2–5 (1cm diameter) areas affecting emotions or functioning | ||||

| Mucositis -Oral -Anal | Mild erythema or edema, and asymptomatic | Symptomatic (mild pain, opioid not required); erythema or limited ulceration, can eat solid foods and take oral medication (oral mucositis only) | Pain requiring opioid analgesic; erythema and ulceration, cannot eat solids, can swallow liquids (Oral mucositis only) | Erythema and ulceration, cannot tolerate PO intake; require tube feeding or hospitalization (Oral mucositis only) |

| Radiation dermatitis | Faint erythema or dry desquamation | Moderate to brisk erythema; patchy moist desquamation, mostly confined to skin folds and creases; moderate edema | Moist desquamation other than skin folds and creases; bleeding induced by minor trauma or abrasion | Skin necrosis or ulceration of full thickness dermis; spontaneous bleeding from involved site |

| Hyposalivation | Can eat but requires liquids, no effect on speech | Moderate/thickened saliva; cannot eat dry foods, mild speech impairment (sticky tongue, lips, affecting speech) | No saliva, unable to speak without water, no oral intake without water | - |

| Taste | Altered or reduced taste; no impact on oral intake | Altered or reduced taste affecting interest and ability to eat; no intervention required | Taste abnormalities, requires intervention | - |

From Multinational Association of Supportive Cancer Care (2016). Supportive care in cancer. Available at: http://www.mascc.org

Recommendations are based on Level II evidence for prevention. Level II evidence consists of randomized trials that have low statistical power. Once treatment begins, MASCC skin toxicity recommends Level IV evidence. Level IV evidence is considered weak evidence from descriptive and case studies. This Level IV evidence includes topical hydrocortisone 1% cream, with moisturizer and sunscreen twice daily, and systemic doxycycline 100 mg PO bid twice daily or minocycline 100 mg daily if the patient is in tropical areas as minocycline is not photosensitizing.

Implications to Nursing Practice

Nursing care of patients receiving EGFR inhibitor therapy focuses on minimizing symptoms and helping patients maximize their quality of life. Table 6 provides the Nursing Care and Management including the Patient and Caregiver education that is necessary for this patient population. Patient educational materials (Table 7) are available, such as Skin Reactions to Targeted Therapies and Immunotherapy (2016) by the American Society of Clinical Oncology, available at http://www.cancer.net/navigating-cancer-care/side-effects/skin-reactions-targeted-therapies or may be institution-specific like the one found at https://www.mskcc.org/cancer-care/patient-education/skin-care-during-treatment-targeted-therapies.

Table 6.

Nursing Management for Skin Conditions

| Patient Problem | Nursing Management | Patient Education |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Anxiety r/t Diagnoses Treatment Prognosis |

|

|

|

| ||

| Fatigue |

|

|

|

| ||

| High risk for infection r/t alteration in skin |

|

|

| Obtain culture and sensitivity as ordered - If the patient’s wound exhibits signs of infection or the wound are not healing a culture should be taken after obtaining an order. This would allow the team to identify the organism and the appropriate antibiotic to treat the infection. It is important to obtain a wound culture | ||

| Using the swab technique. The culture should be collected after the wound tissue is cleansed with a nonantiseptic sterile solution (i.e. Normal Saline).Lippincott: Introduced: April 15, 2016 | ||

|

| ||

| Alteration in skin integrity Skin care/Pruritus |

|

|

|

| ||

| Alteration in comfort | ||

|

| ||

|

|

|

|

| ||

|

|

|

|

| ||

|

|

|

|

| ||

|

|

|

|

| ||

|

|

|

|

| ||

|

|

|

Table 7.

Patient Education Materials

| Interventions to prevent hair loss and damage | Shampoo gently with a mild shampoo every two to four days |

| Use hair conditioner to make combing easier | |

| Use SPF shampoos to prevent further damage | |

| Sleep on satin or silk pillowcases | |

| Products to avoid | Hair spray, hair dye, bleach, or permanents (perm) |

| Clips, barrettes, bobby pins, ponytail holders, or scrunchies | |

| Hair dryers, curlers, curling irons, or hair straightener | |

| Rubber bathing or swimming caps | |

| Braids, corn rows, ponytails | |

| Symptoms requiring medical assistance | White patches in the mouth |

| Bleeding of the gums | |

| Pain when swallowing that is not relieved with analgesics | |

| Fever | |

| Sun protection | Wear sun protective clothing and use sunbrellas/wide-brim hats |

| Avoid the sun as much as possible | |

| Purchase sunscreens that are titanium dioxide-based, no chemicals, broad-spectrum (UVA and UVB), at least 30 SPF | |

| Apply sunscreen daily to any areas that may be exposed to the sun as part of daily routine |

The followingis a more detailed description of the care for dermatologic problems that occur with new cancer treatments.

Rash

Treatment for EGFRi-induced rash (Lacouture et al. 2014) include topical steroids, clindamycin 1% cream, and for systemic treatment, doxycycline 100 mg PO bid or minocycline 100 mg qd. Treatment based on rash severity includes 1) Grade 1: low to mid potency topical steroids such as hydrocortisone or alclometasone cream 0.05% twice daily and topical antibiotic such as clindamycin gel 1% daily until rash resolution. 2) Grade 2: low to mid potency topical steroid as above, and institute oral antibiotic (doxycycline 100mg twice daily or minocycline 100mg twice daily) for a minimum of 4 weeks, and continuing until rash resolves; 3) Grade 3 or intolerable Grade 2: consider EGFRi dose reduction per package insert or protocol, as well as low to mid potent topical steroid and topical antibiotic as above, and oral doxycycline 100 mg bid for a minimum of 4 weeks, continuing until rash resolves. A medrol dose pack, high potency topical steroid for the body, and low dose isotretinoin may be considered

Pruritus

Pruritus management can be challenging and must be managed to prevent the patient from scratching, resulting in secondary infections. The maintstay therapy for pruritus is topical corticosteroids using a mid-potency agent, such as triamcinolone cream to the body and aclometasone to the face. If pruritus progresses, the patient can switch to high-potency topical steroids, such as clobetasol. If a patient’s pruritus is refractory to topical corticosteroids, the patient may be placed on an alternative treatment such as an immunomodulatory agent like tacrolimus or topical antidepressants such as doxepin cream. Menthol-based moisturizers are used for anti-pruritic, nonpharmacolgic therapy. Oral therapy for pruritus can include antihistamines such as diphenhydramine, hydroxyzine, and cetirizine (Lacouture et al, 2011). For refractory pruritus, GABA agonists oral antidepressants (Fischer et al, 2013) and aprepitant have been used in clinic practice.

Xerosis

Patients should be encouraged to use emollients twice daily and should be applied within 15 minutes of showering or bathing for better absorption. Lotions and creams are the easiest to apply, however, ointments provide the most water retention in the skin. Ointments such as over-the-counter petrolatum jelly are effective for treating cracked hands and feet. This works best when patients apply the ointment at night with cotton glove and sock occlusion Xerosis may be prevented by (1) bathing with bath oils or mild moisturizing soap, tepid water and following with regular moisturizing creams; (2) avoidance of extreme temperatures and direct sunlight. Management of mild/moderate xerosis employs (1) emollient creams that are packaged in a jar/tub without irritants; (2) occlusive emollients containing urea, colloidal oatmeal, and petroleum-based creams; (3) exfoliants for scaly or hyperkeratotic areas such as ammonium lactate 12% or lactic acid cream 12%; (4) urea cream (10–40%); (5) salicylic acid 6%; (6) zinc oxide (13–40%); and for severe, (7) medium- to high-potency steroid creams (Valentine et al., 2015).

Also, patients should be encouraged to avoid alcohol, fragrance or dyed shower products; 3) use alcohol-free emollient creams and hypoallergenic make-up; 4) avoid over-the-counter acne medications such as benzoyl peroxide, and scented laundry detergents; 5) avoid sun exposure by using a broad-spectrum sunscreen SPF 30 or higher, when exposed to the sun, and 6) stay hydrated at all times as this will help prevent xerosis and pruritus.

Preventing Infection

Educating patients on how to prevent skin infections is another important responsibility of nurses caring for this patient population. Patients are educated on routine handwashing, general hygiene, and common sense practical interventions. Patients are instructed to wash their hands before and after eating, using the restroom, and applying topical medications. The routine of handwashing should last 30 seconds with increased attention to underneath the fingernails. Excoriations secondary to severe pruritus and scratching while sleeping and awake provide an entry of portal for bacteria that normally lives on the skin. Aside from prescribed medications to reduce pruritus, nurses can educate patients on ways to reduce excoriating such as wearing Band-Aids on the fingertips or cotton gloves at night.

Nail Changes

Lacouture et al. (2011) recommend prevention of paronychia by using diluted bleach soaks and avoiding irritants. Paronychia management involves topical corticosteroids or calcineurin inhibitors (Level II evidence), and systemic tetracyclines, reserving antimicrobials when culture and sensitivity testing is known.

Patients are encouraged to practice proper nail care such as regular nail filing and conservative nail clipping. Patients should avoid frequent use of nail polish remover as they contain harsh chemicals that may weaken the nail. Additionally, nail polishes containing formaldehyde or other harsh chemicals should also be avoided. Patients may use over-the-counter nail polishes or take a daily supplement such as Biotin or Biosil to aid in strengthening the nails. To avoid onycholysis, patients are encouraged to wear comfortable footwear, avoid shoes that are too small, and limit the wear of high heeled shoes.

Prevention involves using protective footwear, avoiding friction with fingertips, toes, and heels; treatment if fissures develop involves (1) application of thick moisturizers or zinc oxide (13–40%) cream, (2) painting the fissure with liquid glue or cyanoacrylate to seal cracks, (3) steroids or steroid tape, hydrocolloid dressings, topical antibiotics; (4) bleach soaks to prevent infection (Level III evidence).

Alopecia

Alopecia is one of the most difficult to manage to anticancer therapies. Nurses must address the physical and emotional aspects of this untoward event. Patients should ask their institution for further resources such as support groups or stores that offer discounts on wigs and hairpieces. It’s important for patients to understand that hair thinning may also be the cause of nutrient insufficiency, genetics, stress, hormonal changes, hair treatments, or other medications. For this reason, nursing assessment is particularly important to determine the etiology of alopecia.

Nurses may assess onset, associated symptoms (ie., pruritus, dysesthesia, flaking), past treatments, contributing factors, such as vitamin D and iron deficiency, hypothyroidism, autoimmune conditions, stress (telogen effluvium), and family history. As with nail changes, patients may take over the counter supplements to improve and speed up hair growth such as Biotin and Biosil. Biosil stimulates collagen production, an important protein for hair, skin and nails, joints and bones. They may also choose to use topical medications such as Minoxidil (ROGAINE). Nurses are relied upon to set reasonable expectations for patients on treatment to increase hair growth. Increased hair growth may take up to 8–12 weeks for noticeable results. Compliance in taking daily vitamins and applying topicals is also crucial for their effectiveness (Duvic et al., 1996).

Patient Education

Patient and caregiver education is fundamental to keeping patients on treatment. They should be educated on signs and symptoms to report, i.e. rash, implications of stopping the drug, and when to notify their health care provider. Patients and their caregivers should be educated to contact health care providers for early evaluation. Early recognition of dAE and prompt intervention is important. Patient and caregiver education includes explaining about the treatment, side- effects, symptom management and care strategies. Patients should receive written information about how to manage their skin reactions. Patients should be able to care for themselves including skin care and other symptom-related issues. Table 7 includes information on patient education.

Oncodermatology: A Subspecialty of Oncology Nursing

Oncology nurses require a knowledge base in terms of early recognition, accurate diagnosis, and management strategies for this unique patient population (Balgula, Rosen, & Lacouture, 2011; Ciccolini & Skripnik Lucas, 2016). The study of dermatologic and mucocutaneous symptom management in oncology is on the rise attempting to understand the pathophysiologic mechanism along with appropriate preventive and management strategies for EGFR-related skin toxicities (Balgula, Rosen, & LaCouture, 2011). Nurses are beginning to specialize in “oncodermatology”, a specialty incorporating principles of both dermatology and oncology. This specialty treats patients with skin cancers, cutaneous lymphoma, dermatologic surgery, and supportive oncodermatology (Ciccolini & Skripnik Lucas 2015; Skripnik Lucas & Ciccolini, 2016).

Supportive care is defined as the prevention and management of cancer or treatment-related effects for patients, families, and caregivers throughout the cancer continuum (MASCC, 2016). Supportive care improves health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and decreases treatment interruptions related to adverse events (AE) (Ristevski, Breen & Regan, 2011; Scotté, 2011). Yet there are barriers to supportive care such as personal knowledge of supportive care, perceived value of supportive care, and practice and organizational issues of time, role-definition, and resources (Ristevski, Breen & Regan, 2011). These barriers result in unmet needs for cancer patients (Husain et al, 2013) in varying ways such as physical, financial, educational, personal control, emotional, societal, and spiritual (Burg et al, 2015).

Oncodermatology supportive care is associated symptom management and underscores the need to improve patient outcomes (Fitch & Steele, 2010; Palmer et al, 2016). Gandhi et al. (2009) reported unanticipated concerns of cancer survivors such as irritated and dry skin, a burning sensation, and hair loss. Patients reported other skin effects as either being physically damaging or being a negative result of cancer treatment, i.e., nail problems including discoloration, a stinging sensation and cracking of the nails, rash, and a loss of skin elasticity. These studies highlight the importance of dermatologic pre-cancer treatment counseling with effective dermatologic interventions throughout cancer therapy (Gandhi, Oishi, Zubal, & Lacouture, 2009).

The role of the oncodermatology nurse is evolving at comprehensive cancer centers such as Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Much work needs to be done to confirm this role as a specialty. Ongoing work includes a scope and standards statement, specific competencies must be developed along with a role delineation study to determine certification or certificate requirements. Additionally, research is necessary testing the efficiency of the currently used empiric treatments. Such research will build the body of knowledge in this growing specialty area. Further prospective research is required to elucidate the role and patient and healthcare team outcomes (Ciccolini, 2015; Ciccolini, 2016).

As another example, in 2014, Ruiz et al. conducted a 24 item online survey with 119 United States oncologists treating patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC) eliciting practice settings, adverse event (AE) management practice patterns and beliefs (including dermatologic-related AE), treatment barriers, and patient education. Within this study, the authors noted that 43% of clinicians followed a comprehensive supportive care plan with only 46% evaluating the outcome of AE management. Interestingly, 70% of clinicians referred patients to non-oncology specialists for unique AEs. However, the most common barriers found for consulting with other specialists were finding interested physicians (43%) and time constraints (40%), which the latter may have hindered treatment optimization for this patient population. Lastly, lack of clinician education in management of AEs were also cited as a barrier in treatment optimization. This study demonstrates the need to increase the concerted effort amongst oncologists and specialists in the approach to managing these untoward events, ensuring patient compliance, improving QoL and unmet needs, and maximization of patient outcomes.

Conclusion

Caring for oncodermatology patients provides many opportunities for nursing education and interventions. With new targeted cancer therapies like EGFRi, management of the dermatologic component is as important as all other body systems. Side effects vary depending on the type of anticancer therapy and dose. Due to the mechanism of action of many anticancer therapies, hair, skin and nails are particularly affected. Often times patients are hesitant to discuss dermatologic issues and it’s important that nurses assess each patient’s largest organ: their skin. Patients need to consider this treatment as chronic therapy, the challenge to nurses is to help patients minimize and manage symptoms and to maximize quality of life.

Key Points.

Cancer treatments are changing

Treatments are targeting newer cellular mechanisms

Side effects to newer treatments differ from previous side effects

Skin reactions are some of the most problematic side effects to cancer treatments

There are now skin reactions to newer cancer therapies

Acknowledgments

Funding for this work comes from the MSK Cancer Center Support Grant/Core Grant (P30 CA008748)

A special thank you to Catherine Hydzik, MS, RN, AOCN, Clinical Nurse Specialist, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center for her intellectual ideas and stimulating thought on this topic.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Margaret Barton-Burke, Immediate Past President, Oncology Nursing Society 2014-2016, Director, Nursing Research, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, 205 East 64th Street, Rm 251 Concourse Level, New York, NY 10065, bartonbm@mskcc.org.

Kathryn Ciccolini, Department of Dermatology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York, CiccoliK@mskcc.org.

Maria Mekas, Department of Dermatology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York, mekasm@mskcc.org

Sean Burke, Research Assistant, Nursing Research, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York, burkes@mskcc.org.

References

- http://www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/info/hp/cancer/if-hp-cancer-guide-supp003-egfri-rash.pdf

- American Society of Clinical Oncology. Skin reactions to targeted therapy and immotherapy. 2016 May; Retrieved from http://www.cancer.net/navigating-cancer-care/side-effects/skin-reactions-targeted-therapy-and-immunotherapy.

- Balgula Y, Rosen ST, Lacouture ME. The emergence of supportive oncodermatology: The study of dermatologic adverse events to cancer therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(3):624–635. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickley LS, Szilagyi PG. Bates’ guide to physical examination and history taking. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Boone SL, Rademaker A, Liu D, Pfeiffer C, Mauro DJ, Lacouture ME. Impact and management of skin toxicity associated with anti-epidermal growth factor receptor therapy: survey results. Oncology. 2007;72(3–4):152–159. doi: 10.1159/000112795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burg MA, Adorno G, Lopez EDS, Loerzel V, Stein K, Wallace C, Sharma DKB. Current unmet needs of cancer survivors: analysis of open-ended responses to the american cancer society study of cancer survivors II. Cancer. 2015;121(4):623–630. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burtness B, et al. NCCN Task force report: Management of dermatologic and other toxicities associated with EGFR inhibition in patients with cancer. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2009;7(1):1–21. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2009.0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccolini K. CREAM Principles: The Advanced Nursing Role in the Management of Dermatologic Adverse Events to Anticancer Therapy. [Abstract] Journal of Advanced Practitioner in Oncology. 2015;7(1) [Google Scholar]

- Ciccolini K. CREAM: Nursing Principles for an Oncodermatology Clinic Dedicated to Managing Dermatologic Adverse Events to Anticancer Therapy. [Abstract] Supportive Care in Cancer. 2016;24(1):S2–S249. [Google Scholar]

- Ciccolini KT, Skripnik Lucas A. Spotlight on Dermatology Nursing. 2015 Retrieved from: https://www.mskcc.org/blog/spotlight-dermatology-nursing.

- Ciccolini KT, Skripnik Lucas A. Exploring the Role of Oncodermatology Nursing; Poster session presented at the meeting of Dermatology Nursing Association Annual Convention; Indianapolis, IN. Mar, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Duvic M, Lemak NA, Valero V, Hymes SR, Farmer KL, Hortobagyi GN, Compton LD. A randomized trial of minoxidil in chemotherapy-induced alopecia. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1996;35(1):74–8. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(96)90500-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eilers RE, Gandhi M, Patel JD, Mulcahy MF, Agulnik M, Hensing T, Lacouture ME. Dermatologic infections in cancer patients treated with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor therapy. J. Natl Cancer. 2009;102(1):47–53. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer A, Rosen AC, Ensslin CJ, Wu S, Lacouture ME. Pruritus to anticancer agents targeting the EGFR, BRAF, and CTLA-4. Dermatologic Therapy. 2013;26(2):135–48. doi: 10.1111/dth.12027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitch MI, Steele R. Supportive care needs of individuals with lung cancer. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal. 2010;20(1):15–22. doi: 10.5737/1181912x2011522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi M, Oishi K, Zubal B, Lacouture ME. Unanticipated toxicities from anticancer therapies: Survivors’ perspectives. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2009;18(11):1461–8. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0769-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas M. Principles of skin care and the oncology patient. Oncology Nursing Society. Pittsburgh, Pa: Oncology Nursing Society; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Husain A, Barbera L, Howell D, Moineddin R, Bezjak A, Sussman J. Advanced lung cancer patients’ experience with continuity of care and supportive care needs. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2013;21(5):1351–8. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1673-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannsen L. Dermatology nursing, skin assessment. 2. Vol. 17. Copyright 2005 by Jannetti Publications, Inc.; 2005. p. 166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacouture ME. Mechanisms of cutaneous toxicities to EGFR inhibitors. Nature Reviews. 2006;6:803–812. doi: 10.1038/nrc1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacouture ME, Anadkat MJ, Bensadoun R-J, Bryce J, Chan A, Epstein JB, Eaby-Sandy B. Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and treatment of EGFR inhibitor-associated dermatologic toxicities. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:1079–1095. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1197-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch TJ, Kim ES, Eaby B, Garey J, West DP, Lacouture ME. Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor-associated cutaneous toxicities: An evolving paradigm in clinical management. The Oncologist. 2007;12(5):610–21. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-5-610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melosky B, Anderson H, Burkes RL, Chu Q, Hao D, Ho V, Laskin JJ. Pan Canadian Rash Trial: A randomized phase III trial evaluating the imipact of prophylactic skin treatment regimen on epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitor-induced skin toxicities in patients with metastatic lung cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2015;34(8):810–15. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.3918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Multinational Association of Supportive Cancer Care. Supportive care in Cancer. 2016 Retrieved from: http://www.mascc.org. [PubMed]

- Palmer SC, DeMichele A, Schapira M, Glanz K, Blauch AN, Pucci DA, Jacobs LA. Symptoms, unmet need, and quality of life among recent breast cancer survivors. The Journal of Community and Supportive Oncology. 2016;14(7):299–306. [Google Scholar]

- Ristevski E, Breen S, Regan M. Incorporating Supportive Care Into Routine Cancer Care: The Benefits and Challenges to Clinicians’ Practice. 2011;38(3):E204–E211. doi: 10.1188/11.ONF.E204-E211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz JN, Belum VR, Creel P, Cohn A, Ewer M, Lacouture ME. Current practices in the management of adverse events associated with targeted therapies for advanced renal cell carcinoma: a national survey of oncologists. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2014;12(5):341–347. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scotté F. The importance of supportive care in optimizing treatment outcomes of patients with advanced prostate cancer. Oncologist. 2011;17(Suppl 1):23–30. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-S1-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skripnik Lucas A, Ciccolini KT. Oncodermatology and the Nursing Specialist. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2017.08.001. Retrieved from: http://nursing.onclive.com/contributor/kathryn-ciccolini-and-anna-skripnik-lucas/2016/02/oncodermatology-and-the-nursing-specialist. [DOI] [PubMed]

- The Skin Physical Examination. [Accessed August 22, 2016]; from http://www.siumed.edu/medicine/dermatology/student_information/skinphysicalexam.pdf.

- Valentine J, Belum VR, Duran J, Ciccolini K, Schindler K, Wu S, Lacouture ME. Incidence and risk of xerosis with targeted anticancer therapies. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2015;72(4):656–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wacher B, Nagrani T, Weinberg J, Witt K, Clark G, Cagnoni PJ. Correlation between development of rash and efficacy in patients treated with epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor erlotinib in two large phase iii studies. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:3913–3921. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkes GM, Barton-Burke M. Oncology Nursing Drug Handbook. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishing; 2016. [Google Scholar]