Abstract

Background

Primary care-based models for Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) have been shown to reduce mortality for Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) and have equivalent efficacy to MAT in specialty substance treatment facilities.

Objective

The objective of this study is to systematically analyze current evidence-based, primary care OUD MAT interventions and identify program structures and processes associated with improved patient outcomes in order to guide future policy and implementation in primary care settings.

Data sources

PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, and PsychInfo.

Methods

We included randomized controlled or quasi experimental trials and observational studies evaluating OUD treatment in primary care settings treating adult patient populations and assessed structural domains using an established systems engineering framework.

Results

We included 35 interventions (10 RCTs and 25 quasi-experimental interventions) that all tested MAT, buprenorphine or methadone, in primary care settings across 8 countries. Most included interventions used joint multi-disciplinary (specialty addiction services combined with primary care) and coordinated care by physician and non-physician provider delivery models to provide MAT. Despite large variability in reported patient outcomes, processes, and tasks/tools used, similar key design factors arose among successful programs including integrated clinical teams with support staff who were often advanced practice clinicians (nurses and pharmacists) as clinical care managers, incorporating patient “agreements,” and using home inductions to make treatment more convenient for patients and providers.

Conclusions

The findings suggest that multidisciplinary and coordinated care delivery models are an effective strategy to implement OUD treatment and increase MAT access in primary care, but research directly comparing specific structures and processes of care models is still needed.

Introduction

Recent spikes in opioid-related overdoses have led experts to advocate for the creation of primary care-based treatment models to expand access to treatment for Opioid Use Disorders (OUD). [1, 2] OUD is categorized by individuals exhibiting signs and symptoms of compulsive behavior related to the self-administration of opioid substances [3]without a legitimate medical cause or in doses excess of what is clinically [2] necessary.[2] Internationally, of an estimated 48.9 million opioid/opiate users, 187,100 experience drug-related deaths annually.[4] In the US alone, about 2.5 million citizens have OUD, with an estimated 60,000 deaths due to drug overdoses [3] occurring annually.[5] A paucity of specialized substance treatment facilities and rising demand for OUD treatment presents primary care-based models the opportunity to increase access to treatment.

Over the past 15 years, health systems have developed and tested models to incorporate the use of medication-assisted treatment (MAT), also referred to as opioid-assisted treatment, into primary care settings. MAT uses pharmacological treatments such as buprenorphine and methadone coupled with psychosocial care to treat patients with OUD. [6] Primary care-based models for MAT appear to have roughly equivalent efficacy and outcomes to specialty substance treatment facilities in certain populations with the added advantage of managing, and potentially improving, comorbidity outcomes[7–12]. A recent scoping review has only looked at U.S. models, but no systematic, rigorous international comparisons with a focus on implementation structures and processes of OUD MAT in primary care settings exist to date [13]. No studies have attempted to synthesize the core implementation structures of these interventions, and as a result, little is known about the components included in effective models in primary care settings. This gap in the literature demonstrates the need to identify which components of primary care models for OUD treatment have shown success in implementation and acceptance by patients.

This systematic review aims to evaluate the literature on interventions for treating OUD in primary care settings using an established systems design framework: Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety (SEIPS) 2.0 [14]. We use this framework to answer the questions: what structural characteristics and implementation components are described in existing primary care models for treating OUD, and how can we improve upon them in the future? Specifically, we aim to: (1) identify thematic components of primary care OUD MAT models that are accepted by patients and physicians and associated with improved health outcomes (2) use those findings to guide future policy and provide recommendations on design features of delivery models found to be effective in the primary care setting.

Methods

Data sources and searches

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) recommendations in conducting this systematic review (PROSPERO 2016: CRD42016033762) [15]. With the assistance of a medical research librarian (MC), we performed serial literature searches for English language articles. MEDLINE via PubMed, CINAHL, EMBASE, and PsychInfo were searched for studies published prior to August 1, 2016 using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and keywords based on primary care settings and treatment of OUDs (S1 Table). All human studies published in full-text were eligible for inclusion, and no publication date or status restrictions were placed. Additional studies of interest were identified by hand searches of bibliographies. Authors were contacted by email if further clarification was needed.

Study selection

Two authors (KK and CB) independently screened titles and abstracts for eligibility. Given the complexity of designing and evaluating care models [16], we included both experimental (RCTs) and observational studies (cohort, case-control, cross-sectional) if they met inclusion criteria. Articles were included if the intervention: (1) evaluated a primary care-based health delivery model where primary care was defined as care delivered in a general practice setting (i.e. private practice, academic primary care clinic) by a general medical internist and/or family medicine physician only, (2) targeted adults (18 years or older) with OUD defined as patients engaged in care to treat their opioid addiction, (3) evaluated patient-level outcomes (e.g. patient retention, urine toxicology screens, satisfaction, effect on health screening for comorbidities, etc.), and (4) evaluated the care model using qualitative or quantitative methods. Studies that did not include a description of the care delivery model evaluated (i.e. only discussed physician perceptions of OUD or drug dosage efficacy studies), focused exclusively on comparing intervention settings (e.g. specialty care versus primary care settings) without a detailed description of the primary care intervention/program design, and concentrated on specialty-based primary care (e.g. HIV care) outside of a primary care physician (PCP) led primary care practice were excluded (S2 Table). In the event of a disagreement in exclusion or inclusion between the two reviewers, a third reviewer (PL) resolved the discrepancy.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two authors (KK and CB) used a standardized form adapted from the Cochrane Collaboration [17, 18] to extract data from the included studies, independently and in duplicate. The following data was extracted for all studies: location, study design, intervention design and duration, care model structures and processes, classification, delivery staff, sample size, patient population, and primary/secondary outcomes as stated by the authors of each study.

Two authors (KK and CB) independently assessed risk of bias via the validated Downs and Black tool which utilizes the following elements to assess risk of bias in both experimental and observational studies: quality of reporting, internal validity of the study and its power, and external validity and confounding [19]. The tool evaluates each of these elements using 27 questions, allowing each article to receive a sum score of up to 32 points. For the purposes of this study, the last question assessing statistical power was interpreted as a dichotomous outcome: 0 for insufficient/no power calculation and 1 for studies that provided evidence of power calculation or reference to statistical power. From this alteration, 28 was the highest score possible. As previously reported [20] [21] the following were the final score ranges: excellent (26–28); good (20–25); fair (15–19); and poor (⩽ 14). Any discrepancies or disagreements in data review, extraction, or assessment of risk of bias were resolved by a third author (PL).

Data synthesis and analysis

Given substantial clinical heterogeneity in patient outcomes reported (i.e. retention, relapse rates, comorbidity management, satisfaction, etc.) and variability in the drug treatments and dosages used in the models (e.g. methadone versus buprenorphine) within the included studies, formal meta-analyses were not performed.

Results

Identification of studies

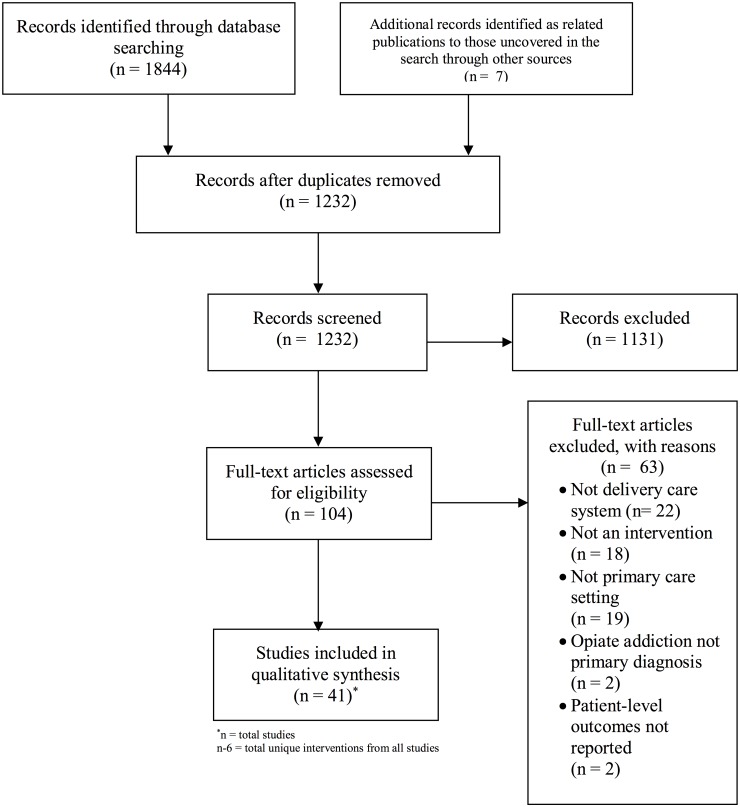

The database search retrieved a total of 1,844 articles and 7 articles identified as related publications to those uncovered in the search through other sources. Initial screening eliminated 1,131 articles at the title and abstract level for not fitting the inclusion criteria. Following full review of each of the remaining 104 articles, 63 articles were eliminated because they did not meet inclusion criteria, leading to 41 included publications (Fig 1). Reasons for exclusion of full-text studies included not a delivery care system, not an intervention, not a primary care setting, opiate addiction not primary care diagnosis, and unreported patient-level outcomes. The qualitative synthesis included 41 publications that described a total of 35 unique interventions. Two included models each had >1 publications that reported different outcomes from the same study (implementation outcomes and patient outcomes), which required inclusion of multiple publications for the same study to best evaluate the model’s efficacy. Of these unique interventions (n = 35), there were 10 randomized controlled trials and 25 quasi-experimental or observational studies.

Fig 1. PRISMA flow diagram.

Study findings

We present the general study characteristics including settings and outcomes within the appropriate SEIPS domains to concisely summarize the findings without duplication of reporting. In addition, we present case-by-case examples of barriers and facilitators for the interventions using the SEIPS organizational framework (Table 1).

Table 1. SEIPS and study characteristics.

| Author | Study Design | Environment | Organization | Person | Tasks | Process | Tech. & Tools | Patient Outcomesa | Provider Outcomes | Quality Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alford et al (2008) |

|

|

|

|

|

Staff:

|

|

|

|

18 Fair |

| Alford et al (2011) |

|

|

|

|

|

Staff:

|

|

|

|

18 Fair |

| Carrieri et al (2014) |

|

|

|

|

|

Staff:

|

|

|

|

23 Good |

| Colameco et al (2005) |

|

|

|

|

|

Staff:

|

|

|

|

17 Fair |

| Cunningham et al (2008) |

|

|

|

|

|

Staff:

|

|

|

|

17 Fair |

| Cunningham et al (2011) |

|

|

|

|

|

Staff:

|

|

|

|

20 Good |

| DiPaula& Menachery (2014) |

|

|

|

|

|

Staff:

|

|

|

|

18 Fair |

| Doolittle & Becker (2011) |

|

|

|

|

|

Staff:

|

|

|

|

15 Fair |

| Drainoni et al (2014) |

|

|

|

|

|

Staff:

|

|

|

|

15 Fair |

| Drucker et al (2007) |

|

|

|

|

|

Staff:

|

|

|

|

17 Fair |

| Ezard et al (1999) |

|

|

|

|

|

Staff:

|

|

|

|

16 Fair |

| Fiellin et al (2002) |

|

|

|

|

|

Staff:

|

|

|

|

23 Good |

| Fiellin et al (2004) Assessed from Fiellin et al (2001) |

|

|

|

|

|

Staff:

|

|

|

|

19 Fair |

| Fiellin et al (2006) |

|

|

|

|

|

Staff:

|

|

|

|

21 Good |

| Fiellin et al (2013) |

|

|

|

|

|

Staff:

|

|

|

|

22 Good |

| Gossop et al (1998) |

|

|

|

|

|

Staff:

|

|

|

|

19 Fair |

| Gossop et al (2003) |

|

|

|

|

|

Staff:

|

|

|

|

17 Fair |

| Gruer et al (1997) |

|

|

|

|

|

Staff:

|

|

|

|

13 Poor |

| Gunderson et al (2010) |

|

|

|

|

|

Staff:

|

|

|

|

21 Good |

| Haddad et al (2014) |

|

|

|

|

|

Staff:

|

|

|

|

18 Fair |

| Hersh et al (2011) |

|

|

|

|

|

Staff:

|

|

|

|

20 Good |

| Kahan et al (2009) |

|

|

|

|

|

Staff:

|

|

|

|

20 Good |

| Lintzeris et al (2004) |

|

|

|

|

|

Staff:

|

|

|

|

20 Good |

| Lucas et al (2010) |

|

|

|

|

|

Staff:

|

|

|

|

23 Good |

| Michelazzi et al (2008) |

|

|

|

|

|

Staff:

|

|

|

|

17 Fair |

| Moore et al (2012) |

|

|

|

|

|

Staff:

|

|

|

|

21 Good |

| Mullen et al (2012) |

|

|

|

|

|

Staff:

|

|

|

|

22 Good |

| O'Connor et al (1998) |

|

|

|

|

|

Staff:

Staff:

|

|

|

21 Good | |

| Ortner et al (2004) |

|

|

|

|

|

Staff:

|

|

|

|

19 Fair |

| Roll et al (2015) |

|

|

|

|

|

Staff:

|

|

|

|

13 Poor |

| Ross et al (2009) |

|

|

|

|

|

Staff:

|

|

|

|

16 Fair |

| Sohler et al (2009) |

|

|

|

|

|

Staff:

|

|

|

|

21 Good |

| Tuchman et al (2006) |

|

|

|

|

|

Staff:

|

|

|

|

20 Good |

| Walley et al (2015) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

20 Good |

| Weiss et al (2011) [22] Fiellin et al (2011)[23] Korthuis et al (2011) Korthuis, Tozzi, et al (2011) Egan et al (2011) Altice et al (2011) [23–26] |

Observational cohort study No Comparison Group Total n = 427 Included in analyses n = 303 Funded program n = 10 |

|

|

|

|

Staff:

|

|

Weiss et al (2011):

|

|

17 Fair |

aPatient outcomes ranged from retention rate, increase in comorbidity screening, etc.

*statistically significant (p < 0.05) outcomes

Definitions of SEIPS domains

The SEIPS 2.0 framework, previously used to evaluate system-level approaches to work systems, was used to evaluate the implementation of included study interventions. [14] The SEIPS model is a widely used healthcare human factors framework adopted by patient safety leaders and applied to multiple health settings including primary care clinics. The three human factor principles this model embraces are 1) evaluating performance from a systems orientation, 2) supporting person centeredness through designing work systems that best fit peoples’ capabilities, limitations and performance needs, and 3) focusing on design-driven improvements to develop structures and processes that enhance patient, provider and organizational outcomes. [14] This framework includes domains regarding the person, organization, technologies and tools, tasks, environment, process, patient outcomes, and employee and organizational outcomes of interventions [14] (Table 2). This framework allowed us to categorize the components across the included studies in a systematic way for better comparisons among interventions considering the heterogeneity of study outcomes and processes. Furthermore, SEIPS guided our assessment of the various components that were included in each model to identify what specific processes were impacted and who was involved.

Table 2. SEIPS model, current state, and areas for improvement.

| SEIPS DOMAINS | DEFINITIONS | CURRENT STATE | AREAS FOR IMPROVEMENT |

|---|---|---|---|

| ENVIRONMENT |

|

|

|

| ORGANIZATION |

|

|

|

| PERSON/TASKS |

|

|

|

| PROCESS |

|

|

|

| TECHNOLOGY & TOOLS |

|

|

|

| PATIENT/ PROVIDER OUTCOMES |

|

|

|

Environment

Studies were conducted in the following countries: U.S. (24), U.K. (3), Australia (2), Canada (2), Austria (1), France (1), Ireland (1), and Italy (1). All studies occurred in primary care centers; however, ten studies compared specialty versus primary care settings [27–36]. Some of the studies (n = 14) were conducted in academic primary care centers [8, 10–12, 37–47] while others (n = 14) occurred in private practice settings [28, 29, 32, 35, 47–55]. Five studies were in community health centers with limited resources [12, 56–59].

Organization

All of the studies meeting inclusion criteria studied buprenorphine (n = 25) and/or methadone (n = 12) treatment in primary care settings. Due to large variability in terminology and reporting, the interventions were grouped into at least one of five care models (e.g. collaborative care vs. integrated care). The most common type was a coordinated care model which had at least two different types of healthcare professionals actively communicating and working together to share care responsibilities (e.g. nurse case manager or pharmacist plus physician). Of the 32 “coordinated care” models, twelve relied upon a nurse case manager or other skilled nursing staff to lead and provide logistical support to the PCP [8, 10, 32, 35, 38, 51, 58, 60–64]. Often the nurse received training to provide some behavioral counseling [38, 58, 60, 65]. Pharmacists also provided assistance to PCPs by supervising medication dosages [49, 51, 53, 66, 67]. Multi-disciplinary models consisted of two physician disciplines working closely together within the same clinic (e.g. addiction psychiatry and internal medicine). For example, one study specifically evaluated the benefit of adding in-clinic behavioral counseling to standard medical management provided by a general internist for patients receiving methadone for heroin use [61]. Shared care models had specialty services lead the medication induction process (the first week of MAT where the physician determines the dosing, timing and treatment goals of the medication) and then later “handed-off” patients to general internal PCPs [33, 45, 56, 58]. In Cunningham et al (2008), patient induction was initiated by the pharmacist before transfer to the physician’s care [56]. The chronic care model, utilized healthcare resources to increase patients’ self-efficacy in managing their chronic disease [57]. Only two studies met this criterion [10, 34]. For example, one study used this framework to design a home induction protocol to empower patients to self-administer medications [34]. Last, the physician-centric model had a single physician or group of physicians working together to provide patient-centered MAT without major structural support from other provider types or disciplines. In Doolittle & Becker (2011), the physician independently counseled and treated the patient [68].

Studies were assigned to models via the criteria outlined above and could be categorized more than once to best capture treatment delivery. Most included studies (n = 32) had coordinated care models with 32 studies falling into two or more care models (e.g. coordinated care and multi-disciplinary care) [8, 10–12, 28–30, 32, 33, 38, 43, 45, 48–51, 56–58, 60, 61, 63, 64, 66, 67, 69–75]. Only three physician-centric studies existed, predominantly in community health centers, where physicians independently provided MAT [34, 68, 76].

Person/Tasks

Thirty-one studies included non-physician providers (e.g. nurses, pharmacists, counselors) to carry out tasks. [8, 10, 11, 27–30, 32, 33, 38, 45, 49–51, 56–60, 62–67, 69–73, 75, 77] The level of training and specific tasks managed by each non-physician provider varied across interventions. First, multiple studies used nurses as liaisons in coordinating care between PCPs and behavioral specialists. [8, 10, 32, 51, 58, 63] This configuration improved performance processes and collaborative work[14]. Both licensed practicing nurses (LPN) and advanced practicing nurses (NPs) were used as program coordinators to lead the intervention while supporting both patients and staff [10, 38, 60]. For example, Lucas et al (2010) had LPNs oversee patient-physician scheduling and assist with induction. Other studies used nursing staff to not only provide care collaboration, but to lead patient visits [8, 10, 32, 38, 51, 60, 62, 64–66]. However, only physicians could prescribe medications. Second, pharmacist roles and tasks varied across interventions. Multiple studies had pharmacists supervise dispensing of buprenorphine or methadone [27–30, 33, 49, 51, 56, 57, 63, 67, 71, 75, 77, 78]. The majority of these were conducted in the Europe [27–30, 51]. One U.S. study used a clinical pharmacist to provide physician guidance regarding appropriate dosing/tapering strategies [75] and to lead most patient follow-up appointments. Third, heterogeneity in formal training among clinicians for providing addiction counseling emerged. Behavioral counseling providers ranged from PhD-trained psychologists [65, 70] to certified addiction counselors [8, 10, 11, 32, 51, 58, 73, 74] to nurses with brief training in addiction counseling [38, 50, 66].

Process

Process focused on the flow of patient care within organizational models. Seven studies had a non-physician (e.g. nurse case manager) perform an initial detailed intake that often consisted of a physical and mental health history, allowing PCPs to focus their time on medication management [10, 38, 45, 49, 60, 74, 75]. Following the intake visit, studies varied on how they handled medication induction. Twenty-nine studies supervised patient induction with frequent appointments and supervised medication dosing [8, 10, 11, 27–30, 32–34, 38, 49–51, 56–58, 60, 62, 63, 65, 67, 69–72, 75–77]. In contrast, four studies evaluated “home” inductions, which increased patient autonomy via a specific plan for how to first begin self-treatment with the chosen medication [55, 57, 68, 71]. Following induction, frequency of appointments with staff ranged from daily to quarter-annually depending upon patient needs and intervention design. Behavioral counseling appointments were often coordinated with medical management appointments [11, 62, 65, 69, 70, 72]. In cases requiring more intense addiction counseling/treatment, nineteen studies had a plan for referral to specialty services [8, 11, 12, 27, 30, 32, 37, 38, 50, 51, 56, 62, 63, 70, 72–75, 79].

Only four studies formally tested if counseling modality or duration affected treatment outcomes [9, 43, 80, 81]. Of these four studies, only two demonstrated that their form of counseling was more efficacious (e.g. patients undergoing CBT had higher rates of negative urine toxicology screens or >80% Quality Health Indicator score) than medical management alone possibly because of their adaptive, stepped-care treatments or highly integrated care teams with numerous support staff [9, 81].

Technology/Tools

Technology/Tools focused on electronic and non-electronic tools that helped manage data and monitor patient outcomes like patient agreements, drug screenings, and electronic information technology systems. Ten studies had formal treatment agreements (“contract”) between patients and providers to outline consequences for continued drug misuse. [8, 11, 37, 38, 51, 68, 69, 75, 77] Most interventions (n = 29) noted that they used urine drug screening as a tool to monitor adherence to medication and drug misuse; although, there was no standardization in what drugs were screened or how often.

Regarding technologies, three studies noted that they had a panel management structure to monitor patient level data (i.e. urine toxicology screens, drug tests, etc.). [10, 75, 81] Four studies noted using electronic medical records to facilitate treatment team member communication and to document patient updates [58, 63, 72, 75]. No studies utilized home-based or web-based counseling modalities [73].

Patient outcomes

Reported patient outcomes varied. However, most studies (n = 25) reported patient-level retention within treatment. At 3 months, nineteen interventions achieved at least 60% retention. Some studies evaluated if patients had self-reported abstinence (n = 15) while others incorporated quantitative measures of abstinence (i.e. urine toxicology screens; n = 22).

Few studies asked about patient perceptions of the care delivery models. One study evaluating a coordinated care model for patients receiving MAT obtained patient feedback regarding care with 90% of patients reporting overall satisfaction with the care model.[52] Additionally, less than half of the interventions (n = 11) assessed management of other common primary-care comorbidities and age-appropriate screenings [10, 12, 38, 45, 49, 50, 57, 58, 60, 64, 68]. One of these studies evaluated what percentage of patients were meeting nine quality health indicators (QHI) of an age appropriate health screening per CDC criteria via retrospective chart review [58]. Greater than 3 months of treatment on buprenorphine was positively associated with achieving a recommended QHI screening score [(AOR) = 2.19; 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.18–4.04)]. Similarly, Roll et al (2015) surveyed 28 patients receiving shared medical appointments for buprenorphine management therapy. They found that 60% of patients reported learning more about comorbidities like Hepatitis C and 43% reported receiving appropriate immunizations since starting the intervention. [54] The BHIVES collaborative was a ten site intervention evaluating the use of buprenorphine/naloxone for patients with both HIV and OUD. The evaluation used mixed-methods and reported patient outcomes on OUD treatment, HIV treatment, HIV related quality of life, patient perspectives on the intervention, and overall quality of life. [12, 22, 23, 25–27, 82].

Provider outcomes

Provider level outcomes were only reported in ten of the included studies [28, 30, 32, 49, 63, 69, 72, 74, 77, 83]. Of these, six studies asked providers qualitatively about barriers and facilitators of the intervention’s success [12, 32, 49, 50, 69, 74].

Themes that emerged from provider outcome data included provider education, cost-related barriers, and benefits of a coordinated-care approach. Three studies noted that providers felt under-trained or that some training in providing the chosen medication (i.e. buprenorphine or methadone) or substance abuse treatment was important. O’Connor et al (1998) found that the intervention itself increased provider confidence in treating patients with OUD. [32, 50, 69, 77]. However, Fiellin et al (2004) reported that physicians felt “adequately prepared for much of the care they provided,” but requested that further training be offered with respect to medication tapering, billing, and additional training for support staff [52]. Nine studies reported that providers felt that there were benefits of coordinated care [8, 38, 49, 51, 58, 60, 75, 77, 81]. In Drainoni et al (2014), providers noted that the RN/Counselor taking ownership of the program was pivotal to program success[8]. Likewise, in Weiss et al (2011), providers noted that coordinated care is crucial in a busy academic setting where physicians had limited availability during clinic hours [12].

Presence of SEIPS domains in good quality studies with high patient retention

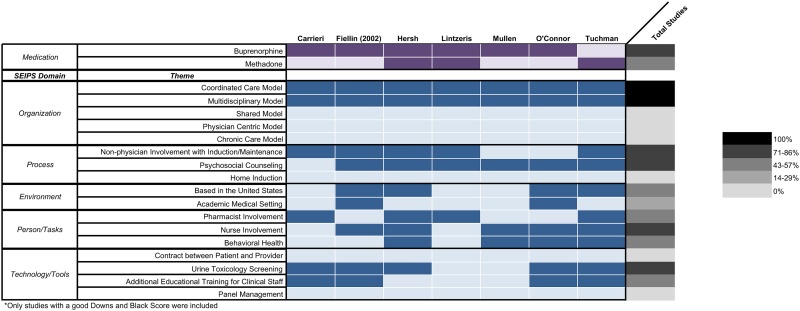

There was heterogeneity in study caliber, medications and dosages, reported patient outcomes, and duration of study making it difficult to perform any meta-analysis with the 35 included studies. However, in order to describe which SEIPS domains may be associated with successful treatment and establish a level of standardization, we defined successful studies as interventions that achieved 60% retention rates at 3 months and received a good score with our validated risk assessment tool. Seven studies met this metric for success (Fig 2) [27, 31, 32, 42, 52, 84, 85].

Fig 2. Presence of SEIPS domains in good quality studies with high patient retention*.

All seven successful studies used coordinated care models with multidisciplinary teams. Six of the studies used buprenorphine as the medication, had a modality for delivering behavioral counseling (although not necessarily through trained behavioral health specialists), used nurses as part of the care team, and monitored treatment outcomes with urine toxicology screens. With respect to technology/tools none of the included studies used patient and provider contracts or panel management structures. In addition, only 4/7 included studies provided additional educational training for the clinical staff.

Risk of bias

No study scored an excellent quality/risk of bias score: sixteen interventions scored good, seventeen scored fair, and two were poor for their reporting of patient outcomes significance (i.e. power within the study to detect differences in outcomes) and their lack of both external and internal validity[51, 54].

Discussion

Few comparisons of primary care models for OUD exist. Our study addresses this gap in knowledge by using the SEIPS domains to categorize features of MAT interventions to better understand specific structural, process and outcome elements of primary care models. The range of studies spanned small physician-led interventions within single clinics to large RCTs with multi-disciplinary teams in academic settings. Based on our synthesis of peer-reviewed literature, we report the current structures and processes of primary care-based OUD MAT models and present a proposed research agenda for future studies within each SEIPS domain.

Coordinated care models (with non-physician team members such as RNs helping manage patient appointments and lab results) are by far the most common delivery structures studied. There was some indication that physicians felt this program model allowed for improved team communication and higher quality of care delivery [8, 12, 47, 51, 52, 66, 86]. Similarly, multidisciplinary teams can promote comprehensive behavioral health counseling in addition to standard PCP-led counseling during routine primary care appointments. However, future studies will need to further delineate the cost and feasibility of these resources in settings where multidisciplinary care is inaccessible or not viable. Ideally, studies would evaluate a physician-centered model against models with varying degrees of care coordination with randomized controlled trials but such studies are costly. With the need to rapidly disseminate primary care based models to provide MAT, this study highlights that policy makers and health care professionals should strive to provide and pragmatically evaluate at the very least, the provision of some coordinated care. These models may include smaller teams or clinical partnerships (i.e. physician-RN teams, physician-pharmacist teams) that are more common across resource settings.

The effective use of clinicians’ skillsets can improve overall care delivery. For example, clinical pharmacists can provide medication dosing and management rather than only supervised medication-taking. In terms of behavioral counseling, more research is needed to identify the optimal level of training necessary for OUD care delivery. Studies have suggested that additional counseling beyond the scope of the physician is ineffectual for certain outcomes [43, 87]. However, future research will need to understand whether certain patient populations benefit more or less from additional counseling to help allocate limited behavioral health resources to those patients that would derive the most benefit.

Home inductions proved successful (≥ 60% retention) for select patients, but future research is still needed to recommend the routine use of home inductions [55, 57, 71] and to identify the patient characteristics that are associated with successful and non-successful home inductions. Furthermore, the use of RNs or other support staff to conduct patient intakes (i.e. physicals, mental health screenings) helped disencumber physician responsibilities. [8, 10, 11, 32, 38, 50, 51, 58, 60, 62–64, 78] Providing patients with “after hours” support was another component of care noted in numerous studies. [39, 45, 55–57, 60, 71, 74] More research is needed to assess the effects of augmenting such support with the use of mobile technology (i.e. telehealth, text messages, emails) to improve the process of providing 24-hour support. Only three studies examined the influence of addiction specialists transferring stabilized patients to primary care [30, 33, 63]. This approach may appeal to primary care workforces wanting to expand access to MAT through a stepped-care approach (i.e. providing stabilized patients maintenance dosing and managing comorbidities), but who are less comfortable providing initial MAT induction.

Wide variation in the use of toxicology screens, patient contracts, and data management structures existed and were largely underdeveloped. Our conclusions correlated with findings from a systematic review examining the use of urine drug screens and treatment agreements in patients with chronic pain, and found that more research is needed to standardize these tools to not only monitor patient level outcomes, but provide population-level feedback to care teams [88]. Additionally, much of the technological aids discussed were relatively nascent with Mullen et al (2012) noting that a more sophisticated data management structure would be helpful [31]. There was substantial heterogeneity with respect to patient and provider outcomes measured. Patient retention was the most common outcome reported, yet there was no uniform definition given dissimilar program lengths between studies (i.e. 1 month to 2 years). Additionally, there was a lack of consideration given to the remitting nature of OUD. Many of the study samples excluded co-dependence on other illicit substances like benzodiazepines, leading to possible confounders that could affect the analyses.

Few studies evaluated provider outcomes such as quality of medical care, physician perceptions, and factors related to care delivery in relation to a primary care-based MAT intervention. While other studies in the literature measure provider barriers to delivering OUD treatment in primary care settings [89–91], these studies do not measure provider outcomes concurrently to testing patient level outcomes within specified care model structures. This gap indicates key areas for future research such as determining the appropriate level of provider training, testing provider training and mentoring support mechanisms such as the Providers' Clinical Support System for Medication Assisted Treatment [92] and Project ECHO (Extension for Community Health Outcomes) a video-based distance education program, and determining how to prevent physician burnout. [85]

Our study could not make any definitive statements regarding whether particular care models or treatment elements are strongly associated with favorable patient outcomes compared to alternatives. However, when we did look across studies with good quality and high patient retention there was a pattern suggesting that successful studies used coordinated, multidisciplinary models to support physicians in delivering MAT. The majority of the seven studies did not use tools such as patient/provider contracts nor did they provide additional clinical staff training suggesting that they may not be necessary to successfully carry out primary care based MAT.

Our study has limitations. First, because of both the heterogeneity in reporting of outcomes and variability in medications used and dosages, we were unable to perform a pooled meta-analysis to clearly link structural domains identified via SEIPS to health outcomes. Second, not all of the studies included had randomized designs. Potential for bias and confounding should be considered, though it was formally assessed within our methods. Third, we were unable to quantitatively evaluate which particular SEIPS domains contributed to intervention success or failure. Fourth, we only included studies that were published in peer-reviewed literature. Therefore, we did not capture interventions that may be in the pilot phase or have outcomes presented via other “grey” literature such as websites/forums.

Our study has several strengths. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review that describes both patient outcomes and structural organization of interventions to treat OUD in primary care settings both domestically and internationally. Second, by using the SEIPS framework, we described systems design elements within each intervention rather than focusing only on the broad organizational framework of the intervention. Not all primary care settings have access to the same resources with some unable to structurally accommodate a multi-person coordinated care team. However, we provide details on how to improve systems (e.g. person, tasks, and process) depending on the resources that are available in various settings.

There is variability in regulations for treatment programs, payment models, and provider training structures which may limit or enhance the ability of health systems to provide high quality multidisciplinary, coordinated care with the most cost-effective, efficacious OUD interventions. As the US allocates funding towards expanding MAT access, programs receiving such funding would benefit from considering the intervention models found to support MAT implementation in prior studies [93]. By evaluating not only patient efficacy, but also structural characteristics of primary care models for delivering MAT, this review provides key insights for PCPs and researchers about ways to build upon existing resources and personnel to more effectively deliver OUD treatment. Specifically, this study identified key components of primary care OUD delivery models. As we continue to grapple with the global rise of opioid-related morbidity and mortality, this review can help enhance the rapid dissemination of effective OUD treatment programs across diverse settings.

Supporting information

(TIFF)

(TIFF)

(TIFF)

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Marisa Conte for assistance with setting up our database searches.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.Burwell S. CDC Opiod Prescribing Guideline Call: HHS.gov; 2016 [cited 2016 May 6, 2016]. http://www.hhs.gov/about/leadership/secretary/speeches/2016/cdc-opioid-prescribing-guideline-call.html.

- 2.Association AP. Opioid Use Disorder—Diagnostic Criteria. In: Association AP, editor. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. Fifth ed. 1–92013. p. 1–9.

- 3.Katz J. Drug deaths in American are rising fasteer than ever New York City: The New York Times Company; 2017 [cited 2017 07/25/2017]. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/06/05/upshot/opioid-epidemic-drug-overdose-deaths-are-rising-faster-than-ever.html

- 4.Crime UNOoDa. World Drug Report 2015.

- 5.Rudd RA, Aleshire N, Zibbell JE, Gladden RM. Increases in Drug and Opioid Overdose Deaths—United States, 2000–2014. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2016;64(50–51):1378–82. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6450a3 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Policy OoNDC. Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opiod Addiction. Executive Office of the President; 2012.

- 7.Brown R, Gassman M, Hetzel S, Berger L. Community-based treatment for opioid dependent offenders: A pilot study. American Journal on Addictions. 2013;22(5):500–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2013.12049.x . Language: English. Entry Date: 20140509. Revision Date: 20150710. Publication Type: Journal Article. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drainoni M-L, Farrell C, Sorensen-Alawad A, Palmisano JN, Chaisson C, Walley AY. Patient Perspectives of an Integrated Program of Medical Care and Substance Use Treatment. AIDS Patient Care & STDs. 2014;28(2):71–81. doi: 10.1089/apc.2013.0179 Language: English. Entry Date: 20140214. Revision Date: 20150710. Publication Type: Journal Article. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haddad MS, Zelenev A, Altice FL. Buprenorphine maintenance treatment retention improves nationally recommended preventive primary care screenings when integrated into urban federally qualified health centers. Journal of urban health: bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2015;92(1):193–213. Epub 2015/01/01. doi: 10.1007/s11524-014-9924-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lucas GM, Chaudhry A, Hsu J, Woodson T, Lau B, Olsen Y, et al. Clinic-based treatment of opioid-dependent HIV-infected patients versus referral to an opioid treatment program: A randomized trial. Annals of internal medicine. 2010;152(11):704–11. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-11-201006010-00003 . Language: English. Entry Date: 20100924. Revision Date: 20150711. Publication Type: Journal Article. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walley AY, Palmisano J, Sorensen-Alawad A, Chaisson C, Raj A, Samet JH, et al. Engagement and Substance Dependence in a Primary Care-Based Addiction Treatment Program for People Infected with HIV and People at High-Risk for HIV Infection. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015;59:59–66. Epub 2015/08/25. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.07.007 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiss L, Egan JE, Botsko M, Netherland J, Fiellin DA, Finkelstein R. The BHIVES collaborative: Organization and evaluation of a multisite demonstration of integrated buprenorphine/naloxone and HIV treatment. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2011;56(Suppl 1):S7–S13. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182097426 2011-04994-002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Korthuis PT, McCarty D, Weimer M, Bougatsos C, Blazina I, Zakher B, et al. Primary Care-Based Models for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder: A Scoping Review. Annals of internal medicine. 2016. doi: 10.7326/M16-2149 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holden RJ, Carayon P, Gurses AP, Hoonakker P, Hundt AS, Ozok AA, et al. SEIPS 2.0: a human factors framework for studying and improving the work of healthcare professionals and patients. Ergonomics. 2013;56(11):1669–86. doi: 10.1080/00140139.2013.838643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. Open medicine: a peer-reviewed, independent, open-access journal. 2009;3(3):e123–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eccles M, Grimshaw J, Campbell M, Ramsay C. Research designs for studies evaluating the effectiveness of change and improvement strategies. Quality & safety in health care. 2003;12(1):47–52. doi: 10.1136/qhc.12.1.47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins J, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Versions 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Green S, McDonald S. Cochrane Collaboration: more than systematic reviews? Internal medicine journal. 2005;35(1):3–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2004.00747.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. Journal of epidemiology and community health. 1998;52(6):377–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hooper P, Jutai JW, Strong G, Russell-Minda E. Age-related macular degeneration and low-vision rehabilitation: a systematic review. Can J Ophthalmol. 2008;43(2):180–7. doi: 10.3129/i08-001 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silverman SR, Schertz LA, Yuen HK, Lowman JD, Bickel CS. Systematic review of the methodological quality and outcome measures utilized in exercise interventions for adults with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2012;50(10):718–27. doi: 10.1038/sc.2012.78 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Altice FL, Bruce RD, Lucas GM, Lum PJ, Korthuis PT, Flanigan TP, et al. HIV treatment outcomes among HIV-infected, opioid-dependent patients receiving buprenorphine/naloxone treatment within HIV clinical care settings: results from a multisite study. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 2011;56 Suppl 1:S22–32. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318209751e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Korthuis PT, Fiellin DA, Fu R, Lum PJ, Altice FL, Sohler N, et al. Improving adherence to HIV quality of care indicators in persons with opioid dependence: the role of buprenorphine. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 2011;56 Suppl 1:S83–90. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31820bc9a5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Egan JE, Casadonte P, Gartenmann T, Martin J, McCance-Katz EF, Netherland J, et al. The Physician Clinical Support System-Buprenorphine (PCSS-B): a novel project to expand/improve buprenorphine treatment. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(9):936–41. Epub 2010/05/12. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1377-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Egan JE, Netherland J, Gass J, Finkelstein R, Weiss L, Collaborative B. Patient perspectives on buprenorphine/naloxone treatment in the context of HIV care. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 2011;56 Suppl 1:S46–53. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182097561 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Korthuis PT, Tozzi MJ, Nandi V, Fiellin DA, Weiss L, Egan JE, et al. Improved quality of life for opioid-dependent patients receiving buprenorphine treatment in HIV clinics. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 2011;56 Suppl 1:S39–45. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318209754c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carrieri PM, Michel L, Lions C, Cohen J, Vray M, Mora M, et al. Methadone induction in primary care for opioid dependence: A pragmatic randomized trial (ANRS Methaville). PLoS ONE. 2014;9(11). 2015-30799-001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gossop M, Marsden J, Stewart D, Lehmann P, Strang J. Methadone treatment practices and outcome for opiate addicts treated in drug clinics and in general practice: results from the National Treatment Outcome Research Study. Br J Gen Pract. 1999;49(438):31–4. Epub 2000/01/06. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gossop M, Stewart D, Browne N, Marsden J. Methadone treatment for opiate dependent patients in general practice and specialist clinic settings: Outcomes at 2-year follow-up. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2003;24(4):313–21. Epub 2003/07/18. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lintzeris N, Ritter A, Panjari M, Clark N, Kutin J, Bammer G. Implementing Buprenorphine Treatment in Community Settings in Australia: Experiences from the Buprenorphine Implementation Trial. The American Journal on Addictions. 2004;13(Suppl 1):S29–S41. doi: 10.1080/10550490490440799 2004-95153-004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mullen L, Barry J, Long J, Keenan E, Mulholland D, Grogan L, et al. A national study of the retention of Irish opiate users in methadone substitution treatment. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2012;38(6):551–8. Epub 2012/07/04. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2012.694516 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O'Connor PG, Oliveto AH, Shi JM, Triffleman EG, Carroll KM, Kosten TR, et al. A randomized trial of buprenorphine maintenance for heroin dependence in a primary care clinic for substance users versus a methadone clinic. Am J Med. 1998;105(2):100–5. Epub 1998/09/04. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ortner R, Jagsch R, Schindler SD, Primorac A, Fischer G. Buprenorphine Maintenance: Office-Based Treatment with Addiction Clinic Support. European Addiction Research. 2004;10(3):105–11. doi: 10.1159/000077698 2005-03896-003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sohler NL, Li X, Kunins HV, Sacajiu G, Giovanniello A, Whitley S, et al. Home- versus office-based buprenorphine inductions for opioid-dependent patients. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2010;38(2):153–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.08.001 . Language: English. Entry Date: 20100423. Revision Date: 20150711. Publication Type: Journal Article. Journal Subset: Biomedical. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tuchman E. A model-guided process evaluation: Office-based prescribing and pharmacy dispensing of methadone. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2008;31(4):376–81. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2008.04.011 2008-15610-005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fiellin DA, Rosenheck RA, Kosten TR. Office-based treatment for opioid dependence: reaching new patient populations. The American journal of psychiatry. 2001;158(8):1200–4. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.8.1200 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alford DP, LaBelle CT, Richardson JM, O'Connell JJ, Hohl CA, Cheng DM, et al. Treating homeless opioid dependent patients with buprenorphine in an office-based setting. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22(2):171–6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0023-1 2010-08114-002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alford DP, Labelle CT, Kretsch N, Bergeron A, Winter M, Botticelli M, et al. Collaborative care of opioid-addicted patients in primary care using buprenorphine: five-year experience. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2011;171(5):425–31. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.541 . Language: English. Entry Date: 20110617. Revision Date: 20150711. Publication Type: Journal Article. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Colameco S, Armando J, Trotz C. Opiate dependence treatment with buprenorphine: one year's experience in a family practice residency setting. J Addict Dis. 2005;24(2):25–32. Epub 2005/03/24. doi: 10.1300/J069v24n02_03 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fiellin DA, Barthwell AG. Guideline Development for Office-Based Pharmacotherapies for Opioid Dependence. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 2003;22(4):109–20. doi: 10.1300/J069v22n04_09 2004-10538-007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fiellin DA, Kleber H, Trumble-Hejduk JG, McLellan AT, Kosten TR. Consensus statement on office-based treatment of opioid dependence using buprenorphine. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2004;27(2):153–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.06.005 2004-19824-006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fiellin DA, Moore BA, Sullivan LE, Becker WC, Pantalon MV, Chawarski MC, et al. Long-term treatment with buprenorphine/naloxone in primary care: results at 2–5 years. Am J Addict. 2008;17(2):116–20. Epub 2008/04/09. doi: 10.1080/10550490701860971 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fiellin DA, Pantalon MV, Chawarski MC, Moore BA, Sullivan LE, O'Connor PG, et al. Counseling plus buprenorphine-naloxone maintenance therapy for opioid dependence. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(4):365–74. Epub 2006/07/28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055255 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gunderson EW, Wang XQ, Fiellin DA, Bryan B, Levin FR. Unobserved versus observed office buprenorphine/naloxone induction: a pilot randomized clinical trial. Addict Behav. 2010;35(5):537–40. Epub 2010/01/29. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kahan M, Wilson L, Midmer D, Ordean A, Lim H. Short-term outcomes in patients attending a primary care-based addiction shared care program. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55(11):1108–9.e5. Epub 2009/11/17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moore BA, Barry DT, Sullivan LE, O’Connor PG, Cutter CJ, Schottenfeld RS, et al. Counseling and directly observed medication for primary care buprenorphine maintenance: A pilot study. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2012;6(3):205–11. 2013-07525-005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ortner R, Jagsch R, Schindler SD, Primorac A, Fischer G. Buprenorphine maintenance: office-based treatment with addiction clinic support. Eur Addict Res. 2004;10(3):105–11. Epub 2004/07/20. doi: 10.1159/000077698 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carrieri PM, Michel L, Lions C, Cohen J, Vray M, Mora M, et al. Methadone induction in primary care for opioid dependence: a pragmatic randomized trial (ANRS Methaville). PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e112328 Epub 2014/11/14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Drucker E, Rice S, Ganse G, Kegley JJ, Bonuck K, Tuchman E. The Lancaster office based opiate treatment program: a case study and prototype for community physicians and pharmacists providing methadone maintenance treatment in the United States. Addictive Disorders & Their Treatment. 2007;6(3):121–35. Language: English. Entry Date: 20080125. Revision Date: 20150711. Publication Type: Journal Article. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fiellin DA, O'Connor PG, Chawarski M, Schottenfeld RS. Processes of Care During a Randomized Trial of Office-based Treatment of Opioid Dependence in Primary Care. The American Journal on Addictions. 2004;13(Suppl 1):S67–S78. doi: 10.1080/10550490490440843 2004-95153-006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gruer L, Wilson P, Scott R, Elliott L, Macleod J, Harden K, et al. General practitioner centred scheme for treatment of opiate dependent drug injectors in Glasgow. Bmj. 1997;314(7096):1730–5. Epub 1997/06/14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hersh D, Little SL, Gleghorn A. Integrating buprenorphine treatment into a public healthcare system: the San Francisco Department of Public Health's office-based Buprenorphine Pilot Program. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2011;43(2):136–45. Epub 2011/08/24. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2011.587704 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lintzeris N, Ritter A, Panjari M, Clark N, Kutin J, Bammer G. Implementing buprenorphine treatment in community settings in Australia: experiences from the Buprenorphine Implementation Trial. Am J Addict. 2004;13 Suppl 1:S29–41. Epub 2004/06/19. doi: 10.1080/10550490490440799 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roll D, Spottswood M, Huang H. Using Shared Medical Appointments to Increase Access to Buprenorphine Treatment. J Am Board Fam Med. 2015;28(5):676–7. Epub 2015/09/12. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2015.05.150017 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sohler NL, Li X, Kunins HV, Sacajiu G, Giovanniello A, Whitley S, et al. Home- versus office-based buprenorphine inductions for opioid-dependent patients. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2010;38(2):153–9. Epub 2009/10/06. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cunningham C, Giovanniello A, Sacajiu G, Whitley S, Mund P, Beil R, et al. Buprenorphine treatment in an urban community health center: what to expect. Fam Med. 2008;40(7):500–6. Epub 2008/10/22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cunningham CO, Giovanniello A, Li X, Kunins HV, Roose RJ, Sohler NL. A comparison of buprenorphine induction strategies: Patient-centered home-based inductions versus standard-of-care office-based inductions. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2011;40(4):349–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.12.002 2011-08603-006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Haddad MS, Zelenev A, Altice FL. Buprenorphine maintenance treatment retention improves nationally recommended preventive primary care screenings when integrated into urban federally qualified health centers. Journal of Urban Health. 2015;92(1):193–213. doi: 10.1007/s11524-014-9924-1 . Language: English. Entry Date: 20150923. Revision Date: 20160204. Publication Type: journal article. Journal Subset: Public Health. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ross D, Lo F, McKim R, Allan GM. A primary care/multidisciplinary harm reduction clinic including opiate bridging. Subst Use Misuse. 2008;43(11):1628–39. Epub 2008/08/30. doi: 10.1080/10826080802241193 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Alford DP, LaBelle CT, Richardson JM, O'Connell JJ, Hohl CA, Cheng DM, et al. Treating homeless opioid dependent patients with buprenorphine in an office-based setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(2):171–6. Epub 2007/03/16. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0023-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fiellin DA, Pantalon MV, Pakes JP, O'Connor PG, Chawarski M, Schottenfeld RS. Treatment of heroin dependence with buprenorphine in primary care. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2002;28(2):231–41. Epub 2002/05/17. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fiellin DA, Pantalon MV, Chawarski MC, Moore BA, Sullivan LE, O'Connor PG, et al. Counseling plus Buprenorphine-Naloxone Maintenance Therapy for Opioid Dependence. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;355(4):365–74. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055255 2006-09991-001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hersh D, Little SL, Gleghorn A. Integrating buprenorphine treatment into a public healthcare system: The San Francisco Department of Public Health's office-based buprenorphine pilot program. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2011;43(2):136–45. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2011.587704 2011-15572-006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Roll D, Spottswood M, Huang H. Using Shared Medical Appointments to Increase Access to Buprenorphine Treatment. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2015;28(5):676–7. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2015.05.150017 . Language: English. Entry Date: 20150923. Revision Date: 20150923. Publication Type: Journal Article. Journal Subset: Biomedical. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fiellin DA, Pantalon MV, Pakes JP, O'Connor PG, Chawarski M, Schottenfeld RS. Treatment of heroin dependence with buprenorphine in primary care. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2002;28(2):231–41. doi: 10.1081/ADA-120002972 2002-01210-003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tuchman E, Gregory C, Simson M, Drucker E. Safety, Efficacy, and Feasibility of Office-based Prescribing and Community Pharmacy Dispensing of Methadone: Results of a Pilot Study in New Mexico. Addictive Disorders & Their Treatment. 2006;5(2):43–51. 2006-08963-001. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ezard N, Lintzeris N, Odgers P, Koutroulis G, Muhleisen P, Stowe A, et al. An evaluation of community methadone services in Victoria, Australia: Results of a client survey. Drug and alcohol review. 1999;18(4):417–23. doi: 10.1080/09595239996284 2000-13550-006. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Doolittle B, Becker W. A case series of buprenorphine/naloxone treatment in a primary care practice. Substance Abuse. 2011;32(4):262–5. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2011.599256 2011-24462-012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Colameco S, Armando J, Trotz C. Opiate Dependence Treatment with Buprenorphine: One Year's Experience in a Family Practice Residency Setting. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 2005;24(2):25–32. doi: 10.1300/J069v24n02_03 2005-04417-003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fiellin DA, Barry DT, Sullivan LE, Cutter CJ, Moore BA, O'Connor PG, et al. A randomized trial of cognitive behavioral therapy in primary care-based buprenorphine. American Journal of Medicine. 2013;126(1):74.e11–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.07.005 Language: English. Entry Date: 20130301. Revision Date: 20151226. Publication Type: journal article. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gunderson EW, Wang X-Q, Fiellin DA, Bryan B, Levin FR. Unobserved versus observed office buprenorphine/naloxone induction: A pilot randomized clinical trial. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35(5):537–40. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.01.001 2010-01902-001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Moore BA, Barry DT, Sullivan LE, O'Connor PG, Cutter CJ, Schottenfeld RS, et al. Counseling and Directly Observed Medication for Primary Care Buprenorphine Maintenance: A Pilot Study. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2012;6(3):205–11. . Language: English. Entry Date: 20120830. Revision Date: 20150712. Publication Type: Journal Article. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mullen L, Barry J, Long J, Keenan E, Mulholland D, Grogan L, et al. A national study of the retention of Irish opiate users in methadone substitution treatment. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2012;38(6):551–8. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2012.694516 2012-27770-007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ross D, Lo F, McKim R, Allan GM. A primary care/multidisciplinary harm reduction clinic including opiate bridging. Substance Use & Misuse. 2008;43(11):1628–39. doi: 10.1080/10826080802241193 2008-14547-009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.DiPaula BA, Menachery E. Physician-pharmacist collaborative care model for buprenorphine-maintained opioid-dependent patients. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association: JAPhA. 2015;55(2):187–92. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2015.14177 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Michelazzi A, Vecchiet F, Leprini R, Popovic D, Deltito J, Maremmani I. GPs' office based metadone maintenance treatment in Trieste, Italy. Therapeutic efficacy and predictors of clinical response. Heroin Addiction and Related Clinical Problems. 2008;10(2):27–38. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Weiss L, Netherland J, Egan JE, Flanigan TP, Fiellin DA, Finkelstein R, et al. Integration of buprenorphine/naloxone treatment into HIV clinical care: lessons from the BHIVES collaborative. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 2011;56 Suppl 1:S68–75. Epub 2011/03/01. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31820a8226 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tuchman E, Drucker E. Lessons learned in OBOT: 3 case studies of women who did not succeed in pharmacy-based methadone treatment. Addictive Disorders & Their Treatment. 2008;7(3):129–41. doi: 10.1097/ADT.0b013e31805dad80 2008-12797-002. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kahan M, Srivastava A, Ordean A, Cirone S. Buprenorphine: New treatment of opioid addiction in primary care. Canadian Family Physician. 2011;57:281–9. . Language: English. Entry Date: 20110812. Revision Date: 20150711. Publication Type: Journal Article. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fiellin DA, Barry DT, Sullivan LE, Cutter CJ, Moore BA, O'Connor PG, et al. A randomized trial of cognitive behavioral therapy in primary care-based buprenorphine. Am J Med. 2013;126(1):74.e11–7. Epub 2012/12/25. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Moore BA, Barry DT, Sullivan LE, O'Connor P G, Cutter CJ, Schottenfeld RS, et al. Counseling and directly observed medication for primary care buprenorphine maintenance: a pilot study. J Addict Med. 2012;6(3):205–11. Epub 2012/05/23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fiellin DA, Weiss L, Botsko M, Egan JE, Altice FL, Bazerman LB, et al. Drug treatment outcomes among HIV-infected opioid-dependent patients receiving buprenorphine/naloxone. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 2011;56 Suppl 1:S33–8. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182097537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fiellin DA, O'Connor PG, Chawarski M, Schottenfeld RS. Processes of care during a randomized trial of office-based treatment of opioid dependence in primary care. Am J Addict. 2004;13 Suppl 1:S67–78. Epub 2004/06/19. doi: 10.1080/10550490490440843 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bonuck K, Drucker E, Tuchman E, Hartel D. Initiating office based prescribing of methadone: experience of primary care providers in New York City. Journal of Maintenance in the Addictions. 2003;2(3):19–34. Language: English. Entry Date: 20040604. Revision Date: 20150711. Publication Type: Journal Article. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Komaromy M, Duhigg D, Metcalf A, Carlson C, Kalishman S, Hayes L, et al. Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes): A new model for educating primary care providers about treatment of substance use disorders. Subst Abus. 2016;37(1):20–4. Epub 2016/02/06. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2015.1129388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Alford DP, LaBelle CT, Kretsch N, Bergeron A, Winter M, Botticelli M, et al. Collaborative care of opioid-addicted patients in primary care using buprenorphine: five-year experience. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(5):425–31. Epub 2011/03/16. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fiellin DA, Schottenfeld RS, Cutter CJ, Moore BA, Barry DT, O'Connor PG. Primary care-based buprenorphine taper vs maintenance therapy for prescription opioid dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(12):1947–54. Epub 2014/10/21. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Starrels JL, Becker WC, Alford DP, Kapoor A, Williams AR, Turner BJ. Systematic review: treatment agreements and urine drug testing to reduce opioid misuse in patients with chronic pain. Annals of internal medicine. 2010;152(11):712–20. Epub 2010/06/02. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-11-201006010-00004 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Molfenter T, Sherbeck C, Zehner M, Quanbeck A, McCarty D, Kim J-S, et al. Implementing buprenorphine in addiction treatment: Payer and provider perspectives in Ohio. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy. 2015;10 doi: 10.1186/s13011-015-0009-2 2015-16878-001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Deering DEA, Sheridan J, Sellman JD, Adamson SJ, Pooley S, Robertson R, et al. Consumer and treatment provider perspectives on reducing barriers to opioid substitution treatment and improving treatment attractiveness. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36(6):636–42. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.01.004 2011-01821-001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Schulte B, Schmidt CS, Kuhnigk O, Schafer I, Fischer B, Wedemeyer H, et al. Structural barriers in the context of opiate substitution treatment in Germany—a survey among physicians in primary care. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2013;8:26 Epub 2013/07/24. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-8-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.PCSSMAT. PCSSMAT PCSS-MAT http://pcssmat.org/) PCSSO Training; [cited 2016].

- 93.Mannelli P, Wu LT. Primary care for opioid use disorder. Substance abuse and rehabilitation. 2016;7:107–9. doi: 10.2147/SAR.S69715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(TIFF)

(TIFF)

(TIFF)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.