Abstract

Primary Angiitis of the central nervous system is a rare and poorly understood variant of vasculitis. We narrate a case of a 46-year-old male who presented with new onset refractory status epilepticus mimicking autoimmune encephalitis. In this case we are reporting clues that could be useful for diagnosis and extensive literature review on the topic.

Keywords: Primary angiitis, CNS angiitis, CNS vasculitis, NORSE, Status epilepticus

1. Introduction

New onset refractory status epilepticus (NORSE) is a complex disorder, characterized by status epilepticus that is refractory to treatment with no identifiable infectious, inflammatory or brain structural abnormalities [1]. NORSE poses considerable distress to physicians due to its heterogeneous etiology and devastating outcome [2]. An identifiable cause in patients with NORSE is discovered in the majority of cases, however in some the cause remains unknown despite extensive investigations [3]. Primary Angiitis of the central nervous system (PACNS) presenting with seizures was reported in the range of 7–29% [4], [5].

PACNS is described as an entity under the “umbrella” of central nervous system (CNS) vasculitis that is confined to the central nervous system [6]. It is an extremely rare disease with an annual incidence of 2.4 cases per 1,000,000 [7]. PACNS has been reported with the greatest frequency in North America [5], [8], Europe [9], [10], [11] and Australia [12]. Literature is lacking publications about PACNS in Saudi Arabia. The only case in the literature is of a patient with CNS vasculitis complicating a primary immunodeficiency disorder [13].

PACNS is a disease of substantial diagnostic and therapeutic challenges to clinicians [14]. Despite the efforts made to assist clinicians in the diagnosis, the decision of biopsy in a patient suspected to have PACNS remains a challenge. Here we describe the diagnostic approach, clinical characteristics, brain imaging, pathological findings and therapeutic challenges of a patient with PACNS presenting with NORSE in King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center (KFSH&RC) in Riyadh. We suggest clues that could be useful for clinicians to suspect PACNS and proceed with biopsy for definitive diagnosis.

2. Case report

A 46-year-old Saudi male right-handed teacher was in his usual state of health until four months prior to his presentation. This was when he started to have a wide-based gait, unsteadiness as well as several attacks of staring and unresponsiveness. It was associated with lip smacking lasting a few seconds as noticed by his colleagues and students at school. The patient would occasionally complain of a holocranial headache lasting hours to days, incapacitating him from doing his duties of teaching and home commitments.

One week prior to his presentation to our institute, he started complaining of severe headache while in class. His colleagues directed him to a local hospital. On his way he developed abnormal movements with loss of consciousness in the car. The semiology of the abnormal movements reflected left-sided tonic-clonic seizures with uprolling of the eyes, urinary incontinence, frothing of saliva that lasted few minutes and was aborted spontaneously. This was followed by a state of confusion for hours.

During the admission at the local hospital, his brother witnessed some tonic posturing of the left arm for an estimated duration of 2 minutes during which the patient was unresponsive to verbal stimuli. The patient was discharged from the local hospital without anti-seizure therapy.

The patient was referred from the local hospital to our center for seizure evaluation. He presented to the Epilepsy clinic at KFSH&RC with altered consciousness and found to have aphasia. He was non-fluent, and following commands by gesture only. He was rushed to the neurophysiology clinic for an urgent electroencephalogram (EEG).

A 30-minute EEG recording revealed non-convulsive status epilepticus (NCSE). It showed a severely abnormal EEG consisting of a slow background of 6–7 Hertz (Hz) with 1–3 Hz focal slowing in the left anterior and mid temporal region. Several seizures during the recording were associated with evolution of sharp waves and spikes recurring at 3–5 Hz over the left mid and posterior temporal region. During this time the patient was unresponsive with eye blinking. This expedited his admission for investigation and management of his seizures.

He was admitted with a diagnosis of NCSE, started on intravenous (IV) phenytoin and long-term EEG monitoring. He continued to have frequent attacks of non-convulsive seizures, despite being on multiple anti-seizure drugs including lamotrigine, carbamezapine, valporic acid and pyridoxine. Long term EEG monitoring captured 13 attacks of seizures during the first 48 h. Electrographic seizure onset occurred with the onset of rhythmic sharply-contoured theta evolving to delta activity maximal in the left temporal region during unresponsiveness for 5-7 minutes.

Computed tomography (CT) brain was unremarkable for any abnormality. Lumbar puncture was performed and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis showed an elevated protein of 747 mg/dl, and white blood cells (WBC) of 51 with 94% lymphocytes. Because the CSF analysis revealed lymphocytic pleocytosis in the presence of NCSE, the patient was started on antiviral and antibiotics for possible meningo-encephalitis. CSF viral and bacterial etiologies as well as, mycobacterium tuberculosis, syphilis, brucella and sarcoidosis were ruled out.

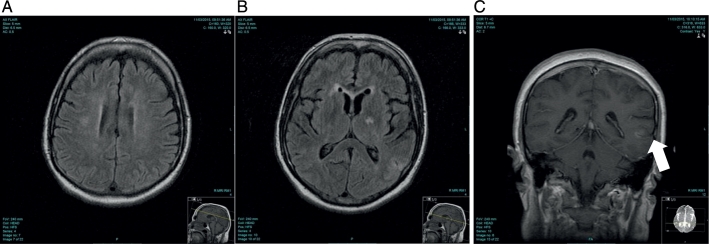

Brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), Magnetic Resonance Angiography and Magnetic Resonance Venography was performed. Brain MRI revealed the presence of multi-territorial, scattered small deep white matter lesions on the fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequence involving the right corona radiate, right inferior cerebellar and cortical areas of the left parietal lobe with corresponding slight enhancement following gadolinium administration. There was no major arterial vascular occlusion, and preserved flow related enhancement of the major dural venous sinuses. The images were thought to be radiologically suggestive of inflammatory vasculitic lesions or ictal hypoxemia. (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

MRI images at presentation

A: Brain MRI FLAIR axial image showing a focal area of hyper intensity in the right peri ventricular white matter and corona radiata

B: Brain MRI FLAIR axial image showing cortical and subcortical hyper intensity in the left parietal lobe

C: Brain MRI T1 post contrast coronal image showing corresponding cortical enhancement of the left parietal lesion.

The seizures became drug-resistant despite extensive investigations and maximum therapy for 48 h with antibiotics, antiviral and the multiple anti-seizure medications. At that point, the diagnosis of NORSE was entertained.

Autoimmune encephalitis was suspected. Serum and CSF autoimmune and paraneoplastic markers were obtained and the patient was started empirically on intravenous steroids for three days. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was mildly elevated. Surprisingly, the patient's autoimmune workup including C-reactive protein, antinuclear antibodies, rheumatoid factor (RF), cytoplasmic anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody titers and cryoglobulins were negative (Table 1, Table 2). A CT scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis was done and revealed no abnormalities. Cerebral angiogram was done as part of the workup for CNS vasculitis and showed no evidence of small vessel disease. (Fig. 2) Despite extensive investigation no identifiable cause could be delineated.

Table 1.

Serum Antibody evaluation.

| A: Paraneoplastic autoantibody evaluation | |

| Anti-neuronal nuclear Ab, type 1 | |

| ANNA-1, S | Negative |

| Reflex added | None |

| Anti-neuronal nuclear Ab, type 2 | |

| ANNA-2, S | Negative |

| Anti-neuronal nuclear Ab, type 3 | |

| ANNA-3, S | Negative |

| Anti-glial nuclear Ab, type 1 | |

| AGNA-1, S | Negative |

| Purkinje cell cytoplasmic Ab type 1 | |

| PCA-1, S | Negative |

| Purkinje Cell Cytoplasmic Ab Type 2 | |

| PCA-2, S | Negative |

| Purkinje cell cytoplasmic Ab type Tr | |

| PCA-Tr, S | Negative |

| Amphiphysin Ab, S | Negative |

| CRMP-5-IgG, S | Negative |

| Striational (striated muscle) Ab, S | Negative |

| P/Q-type calcium channel Ab, S | 0.00 nmol/l |

| N-type calcium channel Ab, S | 0.00 nmol/l |

| ACh receptor (muscle) binding Ab | 0.00 nmol/l |

| AchR ganglionic neuronal Ab, S | 0.00 nmol/l |

| Neuronal (V-G) K + channel Ab, S | 0.01 nmol/l |

| B: Epilepsy-autoimmune antibody evaluation | |

| NMDA-R AB, CBA,CSF | Negative |

| Neuronal (V-G) K + channel Ab, S | 0.01 nmol/l |

| GAD65 Ab assay, S | 0.00 nmol/l |

| GABA-B-R Ab CBA, S | Negative |

| AMPA-R Ab CBA, S | Negative |

| Anti-neuronal nuclear Ab, type 1 | |

| ANNA-1, S | Negative |

| Reflex added | None |

| Anti-neuronal nuclear Ab, type 2 | |

| ANNA-2, S | Negative |

| Anti-neuronal nuclear Ab, type 3 | |

| ANNA-3, S | Negative |

| Anti-glial nuclear Ab, type 1 | |

| AGNA-1, S | Negative |

| Purkinje cell cytoplasmic Ab type 2 | |

| PCA-2, S | Negative |

| Purkinje cell cytoplasmic Ab type Tr | |

| PCA-Tr, S | Negative |

| Amphiphysin Ab, S | Negative |

| N-type calcium channel, Ab | 0.00 nmol/l |

| P/Q-type calcium channel Ab | 0.00 nmol/l |

| Ach receptor (muscle) binding Ab | 0.00 nmol/l |

| AChR ganglionic neuronal Ab, S | 0.00 nmol/l |

| CRMP-5-IgG, S | Negative |

Table 2.

CSF antibody evaluation.

| A: Paraneoplastic autoantibody evaluation | |

| Paraneoplastic autoantibody eval, CSF | |

| Anti-neuronal nuclear Ab, type 1 | |

| ANNA-1, CSF | Negative |

| Reflex added | None |

| Anti-neuronal nuclear Ab, type 2 | |

| ANNA-2, CSF | Negative |

| Anti-neuronal nuclear Ab, type 3 | |

| ANNA-3, CSF | Negative |

| ANTI-Glial Nuclear Ab, Type 1 | |

| AGNA-1, CSF | Negative |

| Purkinje cell cytoplasmic Ab type 1 | |

| PCA-1, CSF | Negative |

| Purkinje cell cytoplasmic Ab type 2 | |

| PCA-2, CSF | Negative |

| Purkinje cell cytoplasmic Ab type Tr | |

| PCA-Tr, CSF | Negative |

| Amphiphysin Ab, CSF | Negative |

| CRMP-5-IgG, CSF | Negative |

| B: Epilepsy-autoimmune antibody evaluation | |

| NMDA-R AB, CBA,CSF | Negative |

| VGKC-complex Ab IPA, CSF | 0.00 nmol/l |

| GAD65 Ab assay, CSF | 0.00 nmol/l |

| GABA-B-R Ab CBA, CSF | Negative |

| AMPA-R Ab CBA, CSF | Negative |

| Anti-neuronal nuclear Ab, type 1 | |

| ANNA-1, CSF | Negative |

| Reflex added | None |

| Anti-neuronal nuclear Ab, type 2 | |

| ANNA-2, CSF | Negative |

| Anti-neuronal nuclear Ab, type 3 | |

| ANNA-3, CSF | Negative |

| Anti-glial nuclear Ab, type 1 | |

| AGNA-1, CSF | Negative |

| Purkinje cell cytoplasmic Ab type 2 | |

| PCA-2, CSF | Negative |

| Purkinje cell cytoplasmic Ab type Tr | |

| PCA-Tr, CSF | Negative |

| Amphiphysin Ab, CSF | Negative |

| CRMP-5-IgG, CSF | Negative |

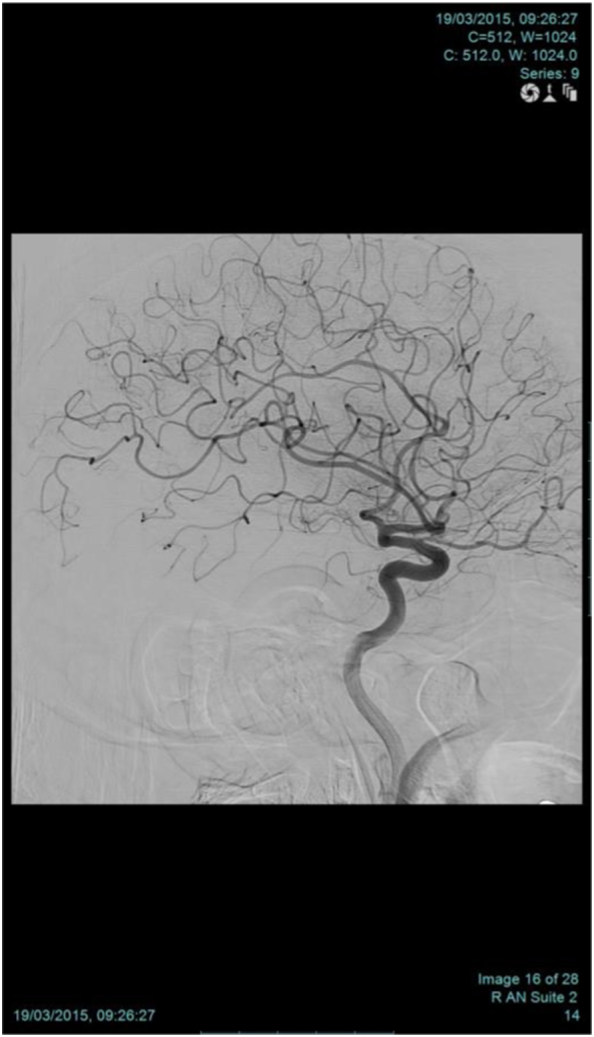

Fig. 2.

Cerebral angiography

Sagittal view of conventional angiography showing no focal area of stenosis or beading appearance to raise a suspicion of vasculitis.

Interestingly, his speech, gait and orientation improved dramatically returning to near normal after the intravenous pulse steroid therapy. He was discharged on oral prednisolone tapering dose, and scheduled for follow up Brain MRI 3 months from the discharge date.

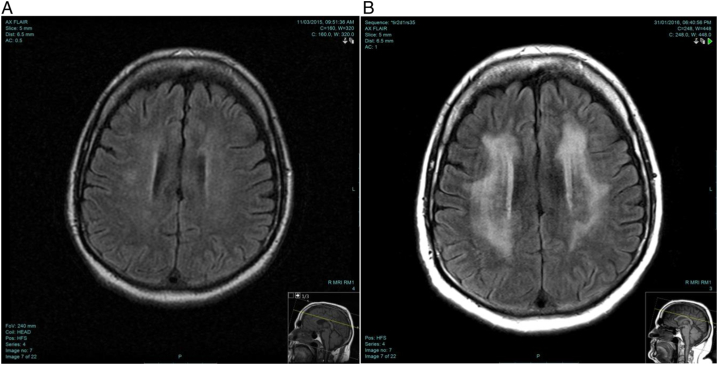

On follow up, he was doing well clinically with great satisfaction in performing the daily activities independently, but still unable to return to work. His repeated brain MRI showed dramatic worsening which was attributed most probably to the tapering of corticosteroid (Fig. 3). He was readmitted for further investigation for investigation of the worsening Brain MRI. LP was repeated and showed elevated protein of 454 mg/dl and WBC of 2 cells.

Fig. 3.

MRI images at presentation and 3 months follow-up

A: Brain MRI at presentation

B: Brain MRI at 3-months follow-up. Axial FLAIR image showing confluent peri-ventricular white matter hyper-intensity sparing the subcortical U fibers.

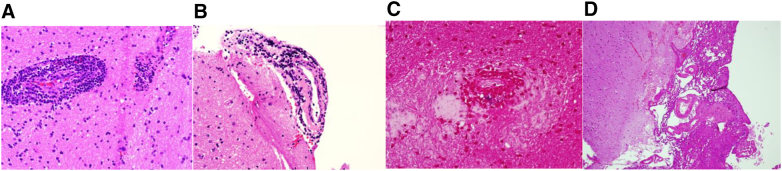

Inclined to reach a diagnosis, brain biopsy was performed and the histopathology picture was suggestive of small vessel vasculitis. The biopsy was composed of many cortical and white matter fragments showing many focal angiocentric mononuclear inflammatory cell infiltrates composed almost exclusively of lymphocytes, predominantly T cells (Fig. 4). Patient was started on cyclophosphamide and showed a dramatic response to the treatment.

Fig. 4.

Pathology slides

A: H & E stain Vessel wall showing inflammation of all the layers of the vessel wall

B: Vessel wall with lymphocytic infiltration. Lymphocytes are small and mature

C: Iron indicating damage of the vessel wall

D: Normal meninges.

3. Discussion

PACNS is a rare and poorly understood variant of vasculitis that is restricted to the CNS [15]. The disease was first described by Cavioto as a distinct entity in 1959 [16], with an increase in the rate of modern detection of cases since the introduction of Calabrese and Mallek diagnostic criteria in 1988 [8]. A cohort study of 163 patients was published in 2015 describing the characteristics of patients with PACNS, which represents the largest study of PACNS reported in adults [5]. Despite the criteria of diagnosis proposed, clinicians still find it difficult to recognize such cases. Decisiveness regarding brain biopsy remains challenging. Early recognition of such cases is crucial in terms of management and outcome.

PACNS clinical presentation seems to show some distinct features in terms of gender and age. The patient in our case report was a 46-year-old male, and as demonstrated in a previous study analyzing 101 patients with PACNS treated at the Mayo Clinic, the median age at diagnosis was 47 years old [7]. It is a disease that shows slight preponderance in men, with a male to female ratio of 4 to 3 [17]. The demographics of the patient in our case report is consistent with that described in the literature, with PACNS affecting middle-aged men.

Clinicians struggle with cases of PACNS due to its heterogeneous presentation with a variable range of signs and symptoms [18]. Most patients in the literature had a diverse presentation, but headache [5], [7], [8] and cognitive decline were the most common reported symptoms at presentation [5], [7]. Although less common, seizures were reported in the range of 7–29% [4], [5]. As reported in our patient, he presented with holocranial headache, cognitive decline and NORSE. Patient seizures were drug-resistant to multiple anti-seizure medications. Thus pointing a suspicion towards a rare etiology such as PACNS, which is not a commonly recognized cause of NORSE.

Cerebrospinal fluid findings play a crucial role in the diagnosis of PACNS. It is abnormal in 80–90% in whom PACNS was pathologically confirmed [6]. In our case the patient's CSF analysis was abnormal, and showed lymphocytic pleocytosis with an elevated protein. CSF examination is extremely useful also in the exclusion of possible causations of the patient's status epilepticus. The CSF examination in our case was negative for any infectious, autoimmune and paraneoplastic antibodies suggesting an underlying alternative rare pathology.

The radiological changes seen in PACNS were demonstrated in a 2003 publication by Singh of four cases at Christian Medical College Hospital in India [19]. As demonstrated in our case, the brain MRI showed features of multi-focal supratentorial lesions representing infarcts involving the cortical, subcortical and deep white matter [19]. The multi-focality of the disease provides a possible rational explanation to the discordance noted in our patient between the seizure semiology of left tonic stiffening and the EEG recording of left temporal NCSE. Our patient also showed significant radiological progression of the disease on his 3 months follow-up brain MRI, which was probably attributed to the tapering of steroid. This was also reported in the 2003 publication by Singh stating that on follow-up MRI studies, new lesions might appear [19].

Conventional angiographic findings demonstrating small vessel disease in patients with PACNS include segmental arterial narrowing and dilatation, vascular occlusion, collateral formation, and prolonged circulation time [20]. It has a sensitivity of 0% and a specificity of 60% in a study comparing conventional angiography and brain biopsy in the diagnosis of PACNS [21]. Typical angiographic finding of PACNS can also be seen in nonvasculitis disorders [5], which mandates performing a brain biopsy to confirm the diagnosis [21]. In our case report, the conventional angiogram showed no major vascular occlusion, which necessitated doing a brain biopsy to establish the diagnosis.

Brain biopsy is a fundamental aspect in the diagnosis of PACNS because of the low sensitivity and specificity of other indicators in the detection of the disease [22]. Diagnostic yield and safety of brain biopsy for suspected PACNS was studied in Langone Medical Center [23]. Pathologically proven vasculitis was established in 11% of those who underwent brain biopsy for suspected PACNS [23]. An alternative diagnosis was established in 30% [23], which highlights the importance of biopsy. Given the fact that brain biopsy is a cardinal tool in the diagnosis of PACNS [22], important in excluding other diseases and has rare meaningful complications [23], clinicians should persevere and proceed with biopsy in order to reach a definitive diagnosis as proven in our case.

4. Conclusion

We present a case of NORSE due to PACNS, which is a very rare and challenging presentation of the disease. In patients with a high clinical suspicion of PACNS, physicians should persevere during evaluation and proceed with biopsy in order to reach an accurate diagnosis and exclude mimickers of PACNS. The early diagnosis of PACNS can lead to a disease-specific treatment with immunotherapy, which can improve the outcome of such patients.

Footnotes

Disclosure: All authors have nothing to disclose

References

- 1.Wilder-Smith E.P., Lim E.C., Teoh H.L., Sharma V.K., Tan J.J., Chan B.P. The NORSE (new-onset refractory status epilepticus) syndrome: defining a disease entity. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2005 Aug;34(7):417–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gall C.R., Jumma O., Mohanraj R. Five cases of new onset refractory status epilepticus (NORSE) syndrome: outcomes with early immunotherapy. Seizure. 2013 Apr;22(3):217–220. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2012.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Costello D.J., Kilbride R.D., Cole A.J. Cryptogenic new onset refractory status epilepticus (NORSE) in adults-infectious or not? J Neurol Sci. 2009 Feb 15;277(1–2):26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Néel A., Pagnoux C. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009 Jan-Feb;27(1 Suppl 52):S95–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salvarani C., Brown R.D., Jr., Christianson T., Miller D.V., Giannini C., Huston J., 3rd An update of the Mayo clinic cohort of patients with adult primary central nervous system vasculitis: description of 163 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015 May;94(21) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hajj-Ali R.A1., Calabrese L.H. Central nervous system vasculitis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2009 Jan;21(1):10–18. doi: 10.1097/bor.0b013e32831cf5e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salvarani C., Brown R.D., Jr., Calamia K.T., Christianson T.J., Weigand S.D., Miller D.V. Primary central nervous system vasculitis: analysis of 101 patients. Ann Neurol. 2007 Nov;62(5):442–451. doi: 10.1002/ana.21226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calabrese L.H., Mallek J.A. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system. Report of 8 new cases, review of the literature, and proposal for diagnostic criteria. Medicine (Baltimore) 1988 Jan;67(1):20–39. doi: 10.1097/00005792-198801000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scolding N.J., Wilson H., Hohlfeld R., Polman C., Leite I., Gilhus N. EFNS cerebral vasculitis task force. The recognition, diagnosis and management of cerebral vasculitis: a European survey. Eur J Neurol. 2002 Jul;9(4):343–347. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2002.00422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Boysson H., Zuber M., Naggara O., Neau J.P., Gray F., Bousser M.G. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system: description of the first fifty-two adults enrolled in the French cohort of patients with primary vasculitis of the central nervous system. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014 May;66(5):1315–1326. doi: 10.1002/art.38340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Küker W., Gaertner S., Nagele T., Dopfer C., Schoning M., Fiehler J. Vessel wall contrast enhancement: a diagnostic sign of cerebral vasculitis. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2008;26(1):23–29. doi: 10.1159/000135649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oon S., Roberts C., Gorelik A., Wicks I., Brand C. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system: experience of a Victorian tertiary-referral hospital. Intern Med J. 2013 Jun;43(6):685–692. doi: 10.1111/imj.12038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.AlKhater S.A. CNS vasculitis and stroke as a complication of DOCK8 deficiency: a case report. BMC Neurol. 2016 Apr 26;16(1):54. doi: 10.1186/s12883-016-0578-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.John S., Hajj-Ali R.A. CNS vasculitis. Semin Neurol. 2014 Sep;34(4):405–412. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1390389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salvarani C., Brown R.D., Jr., Hunder G.G. Adult primary central nervous system vasculitis: an update. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2012 Jan;24(1):46–52. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32834d6d76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.CRAVIOTO H., FEIGIN I. Noninfectious granulomatous angiitis with a predilection for the nervous system. Neurology. 1959 Sep;9:599–609. doi: 10.1212/wnl.9.9.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lie J.T. Primary (granulomatous) angiitis of the central nervous system: a clinicopathologic analysis of 15 new cases and a review of the literature. Hum Pathol. 1992 Feb;23(2):164–171. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(92)90238-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scolding N.J1., Jayne D.R., Zajicek J.P., Meyer P.A., Wraight E.P., Lockwood C.M. Cerebral vasculitis—recognition, diagnosis and management. QJM. 1997 Jan;90(1):61–73. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/90.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh S., John S., Joseph T.P., Soloman T. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system: MRI features and clinical presentation. Australas Radiol. 2003 Jun;47(2):127–134. doi: 10.1046/j.0004-8461.2003.01140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alhalabi M1., Moore P.M. Serial angiography in isolated angiitis of the central nervous system. Neurology. 1994 Jul;44(7):1221–1226. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.7.1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kadkhodayan Y., Alreshaid A., Moran C.J., Cross D.T., 3rd, Powers W.J., Derdeyn C.P. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system at conventional angiography. Radiology. 2004 Dec;233(3):878–882. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2333031621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alrawi Athear, Trobe Jonathan D., Blaivas Mila, Musch David C. Brain biopsy in primary angiitis of the central nervous system. Neurology. 1999;53:858–860. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.4.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Torres J., Loomis C., Cucchiara B., Smith M., Messé S. Diagnostic yield and safety of brain biopsy for suspected primary central nervous system angiitis. Stroke. 2016 Aug;47(8):2127–2129. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.013874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]