Abstract

The advancement of implementation science is dependent on identifying assessment strategies that can address implementation and clinical outcome variables in ways that are valid, relevant to stakeholders, and scalable. This paper presents a measurement agenda for implementation science that integrates the previously disparate assessment traditions of idiographic and nomothetic approaches. Although idiographic and nomothetic approaches are both used in implementation science, a review of the literature on this topic suggests that their selection can be indiscriminate, driven by convenience, and not explicitly tied to research study design. As a result, they are not typically combined deliberately or effectively. Thoughtful integration may simultaneously enhance both the rigor and relevance of assessments across multiple levels within health service systems. Background on nomothetic and idiographic assessment is provided as well as their potential to support research in implementation science. Drawing from an existing framework, seven structures (of various sequencing and weighting options) and five functions (Convergence, Complementarity, Expansion, Development, Sampling) for integrating conceptually distinct research methods are articulated as they apply to the deliberate, design-driven integration of nomothetic and idiographic assessment approaches. Specific examples and practical guidance are provided to inform research consistent with this framework. Selection and integration of idiographic and nomothetic assessments for implementation science research designs can be improved. The current paper argues for the deliberate application of a clear framework to improve the rigor and relevance of contemporary assessment strategies.

Keywords: Implementation science, Assessment, Measurement, Nomothetic, Idiographic, Research design

Intentional research design in implementation science: implications for the use of nomothetic and idiographic assessment

Research design and measurement in implementation science

Implementation science is focused on improving health services through the evaluation of methods that promote the use of research findings (e.g., evidence-based practices) in routine service delivery settings [1]. Studies in this area are situated at the end of the National Institutes of Health translational research pipeline (i.e., at T3 or T4); which describes how innovations move from basic scientific discovery, to intervention, and to large scale, sustained delivery in routine community practice [2]. Implementation research is also inherently multilevel, focusing on individuals, groups, organizations, and systems to change professional behavior and enact service quality improvements [3]. Frequently, the objectives of implementation science include the identification of multilevel variables that impact the uptake of evidence-based practices as well as specific strategies for improving adoption, implementation, and sustainment [4, 5].

As research studying the implementation of effective programs and practices in health care has advanced, diverse research designs have emerged to support nuanced evaluation [6, 7]. All implementation studies involve design decisions, such as determinations about whether the identified research questions call for comparisons within-site, between-sites, or both; whether and how to incorporate randomization; as well as how to balance internal and external validity [6, 8]. In implementation science, there is also growing emphasis on practical research designs that remain rigorous while incorporating the local context and stakeholder perspectives with the goal of accelerating and broadening the impact on policy and practice [9, 10]. Design decisions often have clear implications for the selection of assessment approaches (e.g., identification of instruments, determinations about how resulting data will be compiled and analyzed), which are one of the most concrete manifestations of study design. Nevertheless, implementation research designs – and, by extension, assessment paradigms – remain underdeveloped relative to those for more traditional efficacy or effectiveness studies [6]. The current paper offers strategic guidance to achieve practical research design solutions for complex implementation research by intentionally blending two disparate, but complementary measurement traditions: idiographic and nomothetic.

Different terms are relevant to the use of idiographic and nomothetic assessment. As described in more detail below, idiographic assessment goes by multiple names, each of which underscores its individualized focus. These terms include “intra-unit,” “person/unit-centered,” and “single-case;” in which “unit” refers to individual clinicians, service teams, or organizations, among others. In contrast to idiographic assessment, nomothetic assessment is also known by terms, such as “inter-unit,” “variable centered,” or “group” that communicate its focus on data collected from multiple individuals or organizations to evaluate an underlying construct and classify or predict outcomes. Although we discuss the implications of the other terms and conceptualizations below and sometimes apply them descriptively (e.g., the implications of single-case experimental research for the idiographic approach; nomothetic assessment being variable-centered and producing inter-unit information), we use the terms idiographic and nomothetic to refer directly to these two assessment approaches in this paper.

Intentional measurement decisions

“What gets measured gets done,” has long been a rallying cry for health care professionals interested in performance measurement and quality improvement [11]. Simultaneously, cautions that “If everything gets measured, nothing gets done” [12] underscore the need for deliberate and parsimonious measurement. Examples of literature emphasizing effective assessment and outcome surveillance can be found in such diverse fields and sectors as public health [13], medicine [14, 15], education [16, 17], mental/behavioral health [18], athletic training [19], business management [20], agriculture [21], and government [22]. As detailed by Proctor and colleagues [23], “improvements in consumer well-being provide the most important criteria for evaluating both treatment and implementation strategies” (p. 30). Because implementation science may focus on intervention outcomes (e.g., service system improvements, individual functioning) or implementation outcomes (e.g., fidelity, acceptability, cost), research designs rely on utilizing assessment strategies that can effectively identify and address both types of outcomes in ways that are practical, valid, and relevant to a wide range of stakeholders.

Regarding intervention outcomes, problem identification and outcome measurement strategies are receiving international attention [24–26], and are central to studies evaluating the effectiveness of programs, demonstrating the efficiency of such programs to funders, and determining where to target quality improvement efforts [27]. Outcomes of interest may include reductions in symptoms or disease states, improved service recipient functioning, adjustments in services received, or changes to the environmental contexts in which service recipients interact, among others [28].

Implementation science also frequently focuses on the rigorous measurement of implementation outcomes (e.g., feasibility, fidelity, sustainment, cost; [4, 29, 30]) across multiple levels. Indeed, many models of implementation science and practice rely on targeted measurement of key variables, such as the organizational context, intervention acceptability, the quality of practitioner training and post-training supports, or the delivery of key intervention content [18, 31, 32]. Additionally, due to its multilevel nature, the assessment of implementation outcomes carries particular challenges [13]. For example, implementation measurement instruments oftentimes lack established psychometric properties or are impractical for use in community contexts [18, 29, 33].

Despite advances, strategic guidance is necessary to improve intentional research design and associated measurement of intervention and implementation outcomes in a manner that supports rigorous and relevant implementation science. Such a comprehensive design approach necessitates attention to target outcome specification, instrument selection and application, and grounding in the breadth of relevant measurement traditions. Further, there is growing recognition that complex assessment batteries developed for traditional efficacy studies focused on individuals and organizations are unlikely to be appropriate or feasible for use in implementation research [23]. Multiple assessment perspectives, beyond those typically used in efficacy trials, are necessary to effectively address implementation research questions.

Two assessment traditions – nomothetic and idiographic – are relevant to the comprehensive, intentional design of implementation research studies. Nomothetic assessment focuses on inter-unit information that allows for comparison of a specific unit of analysis (e.g., individuals, teams, organizations) to data aggregated from similar assessments across multiple units on an identified construct of interest (e.g., depression symptoms, organizational readiness), typically for the purposes of classification and prediction. In contrast, idiographic assessment focuses on intra-unit variability and is primarily concerned with information that allows for the comparison of a specific unit of analysis to itself across contexts or time on a target variable. Both methods are relevant across a wide variety of system levels (e.g., individual, team, organization) and target assessment domains. As indicated below, the distinction between these two assessment traditions lies more in design-driven assumptions about how to interpret the resulting data than on the data collection process or tool itself. Although both nomothetic and idiographic assessment approaches are used in the contemporary literature, it is rare that these approaches are explicitly defined, differentiated, or justified in the context of the research design, question, or assumptions and implications of findings. Most of the extant literature appears to reflect the nomothetic tradition, with a preponderance of research focused on the development and use of instruments intended to yield nomothetic data [29, 34]. Virtually no guidance exists to support the intentional use of these two assessment approaches in implementation research, which provides opportunities for the strategic integration of nomothetic and idiographic data. This is particularly unfortunate given that deliberate integration of these two methods has the potential to balance and maximize the measurement rigor and practical qualities of existing assessment approaches.

To advance health care implementation research, the current paper reviews information about nomothetic and idiographic approaches to inform their practical selection – and, when appropriate, integration – to match a range of implementation research questions and study designs. As indicated above, effective assessment in implementation science requires attention to both implementation and intervention outcome constructs, identification of feasible yet rigorous methods, and integration of multiple types of data. Below, we review nomothetic and idiographic assessment traditions and detail their theoretical foundations, characteristics, study designs to which they are best suited, and example applications. Finally, strategic guidance is provided to support the intentional integration of nomothetic and idiographic assessments to answer contemporary implementation research questions.

Nomothetic and idiographic approaches

Nomothetic and idiographic assessment approaches may be differentiated by the ways in which the data resulting from measurement instruments are intended to be used and interpreted in the context of a research design. As a result, data measured with any given instrument may be used in either an idiographic or nomothetic manner, depending on the specific research questions of interest. For this reason, the evidence for a particular instrument’s idiographic or nomothetic use should be evaluated based on the score (rather than instrument) reliability and validity across the circumstances most relevant to the intended use of the instrument in a particular study.

Nomothetic assessment

Nomothetic assessment is primarily concerned with classification and prediction, and closely associated with the framework of classical test theory [35]. This assessment approach emphasizes collecting information that allows for comparison of a specific unit of analysis (e.g., individuals, teams, organizations) to other units or to broader normative data. Consistent with this goal, these assessment strategies are based on nomothetic principles focused on discovering general laws that apply to large numbers of individuals, teams, or organizations [36]. The nomothetic approach usually deals with particular constructs or variables (e.g., intelligence, depression, organizational culture), as opposed to idiographic approach, which is focused on individual people or organizations. As such, assessment instruments intended to produce nomothetic data are typically developed, tested and interpreted through classical test theory, in which large amounts of assessment data are assumed to provide an estimate of a relatively stable underlying construct that cannot be directly assessed for an entire population. Nomothetic assessment focuses on learning more about the construct (as opposed to the person or individual unit) via correlations with instruments designed to assess other constructs. Within classical test theory, variation in an individual’s scores is typically seen as measurement error.

Instruments intended to yield nomothetic data are typically standardized, meaning they have rules for consistent administration and scoring. In their development process, they are ideally subjected to large-scale administration across numerous units. These data can then be used to evaluate an instrument’s nomothetic score reliability (defined as whether the instrument will yield consistent scores across administrations) and score validity (correlational approaches to establish whether it is measuring what it purports to assess). The means and standard deviations of the scores from these large-scale administrations are used to generate norms for the instrument, which can be used to classify individual scores in terms of where they fall relative to the larger population. For example, the distribution of scores on an instrument within a specific sample could be used to create a “clinical cutoff” that identifies individuals who score two standard deviations above the population mean.

In some research designs, instruments may be selected for the nomothetic purposes of classification, prediction, or inter-unit comparisons. Relevant work in implementation science focused on classification might seek to place units into meaningful groups. As an implementation example, Glisson and colleagues [37] have created a profile system, the Organizational Social Climate (OSC) instrument, to characterize the organizational climate of mental health service organizations. Such classification activities can also facilitate probability-based prediction studies. For instance, Glisson and colleagues [37] found that agencies with more positive OSC profiles sustain new practices for longer than agencies with less favorable organizational climates. Research designs intended to evaluate inter-unit differences may use instruments with established norms to make nomothetic comparisons between providers or agencies exposed to different implementation approaches [38, 39] or to collect and compare benchmarking data from one implementation site against randomized controlled trial data [40].

Idiographic assessment

Idiographic assessment, is concerned with the individual performance, functioning, or change of a specific unit of analysis (e.g., individual, team, organization) across contexts and/or time. It is therefore appropriate for research designs intended to document intra-unit differences – either naturally occurring or in response to a manipulation or intervention. Unlike the nomothetic approach, in which meaning is derived relative to normative or correlational data, the point of comparison in idiographic assessment is the same identified unit. Indeed, the strength of idiographic assessment is the ability to identify relationships among independent and dependent variables that are unique to a particular unit. For this reason, examples of instruments designed to yield idiographic data may also allow for item content to be tailored to the individual unit (e.g., ratings of service recipients’ “top problems” [41]). Idiographic assessment is particularly useful for progress monitoring (e.g., across implementation phases or over the course of an intervention) or to compare a single unit’s performance in different scenarios (e.g., an individual’s or organization’s success using different evidence-based interventions, serially or in parallel) to inform the tailoring of specific supports to promote that unit’s success. However, as the point of comparison in idiographic assessment is always a single person, group, or organization, it is less useful for comparisons across units than nomothetic assessment.

The idiographic assessment tradition is closely associated with single-case experimental designs. A requirement of single-case experimental design is it must be possible to assess the process under study in a reliable way over repeated occasions [42]. The psychometric properties of idiographic assessment thus emphasize situational specificity (processes will vary across contexts) and temporal instability (processes will vary over time). A major strength of idiographic assessment is its ability to detect meaningful intra-unit differences in performance across contexts and time along with the factors that might account for those differences.

The use of idiographic assessment aligns with generalizability theory [43], which is a statistical framework for developing and evaluating the properties of instruments that yield intra-unit data. In contrast, classical test theory typically emphasizes psychometric properties (e.g., internal consistency, high test-retest reliability) that work against the core tenets of idiographic assessment (e.g., repeated assessment across time and context). As opposed to classical test theory that considers only one source of error, generalizability theory evaluates the performance of an instrument across facets relevant to different applications of the instrument. Five facets are usually considered: forms, items, observers, time, and situation [43, 44]. The application of generalizability theory to idiographic assessment allows researchers to pinpoint potential sources of variation (facets) that systematically influence scores. If, for example, the context in which an instrument is used (e.g., inpatient versus outpatient service setting within a single organization) accounts for significant variation in scores, then scores would not be considered to be consistent across situation. This variation may be problematic if the instrument is intended to measure a construct hypothesized to remain constant across situation (e.g., practitioner professionalism), but not for constructs where variability is anticipated (e.g., amount of time practitioners devote to each patient). In fact, variation can provide very useful information if understanding differences across contexts or time is relevant to the study (e.g., effectiveness of an intervention for patients in clinic versus home or community settings).

It is important to note that many of the psychometric concepts relevant to nomothetic assessment (e.g., test-retest reliability) do not directly apply to idiographic assessment [45]. In fact, there have been debates about which psychometric categories are relevant when instruments are applied idiographically [44, 45]. Perhaps for this reason, recent efforts to identify important psychometric dimensions have focused primarily upon nomothetic assessment [46] and do not identify important properties of idiographic assessment (although there are exceptions in which idiographic assessment approaches are described in the context of mental health service delivery [47]).

Implementation research has started to investigate the use of single-case experimental designs. These designs differ from observational case studies in that conditions are typically varied within subject over time. Idiographic assessment is best suited to support single-case series research in which information about the performance of a particular unit is studied across contexts and/or time. From a practical standpoint, single-case experimental designs offer cost advantages relative to group designs, especially when research is focused on changes at the unit level (e.g., agency or community level [42]). From an empirical standpoint, some have suggested that single-case experimental designs (i.e., in which a unit is randomized to different conditions sequentially, and assessments compared to a baseline period) are the ideal way to understand the relation between independent and dependent variables and the contextual variables that impact them at the individual, organization, or community level [42, 48]. Single-case experimental designs are thus ideal for theory building [36] related to implementation science that could subsequently be tested in group-based designs [49]. Group-based designs (e.g., randomized control trials; RCTs) are good vehicles for evaluating whether principles identified at the idiographic level generalize to groups. However, to achieve these aims, the measurement approaches need to be matched to the design, something that does not consistently occur.

Opportunities for integrating nomothetic and idiographic assessment methods

The inter-unit vs. intra-unit approaches of nomothetic and idiographic assessment, respectively, may suggest differences in their application as well as a certain level of mutual exclusivity. Though differences between these approaches are apparent, nomothetic and idiographic approaches are complementary. As indicated above, the primary distinctions lie in the manner in which information or scores from instruments are used and interpreted. Consequently, data collected from many instruments may be flexibly used in an idiographic or nomothetic manner given the appropriate research design considerations. Scores from the same instrument may be employed to track a single unit’s change over time (idiographically) or by aggregating across units and determining meaningful cutoffs (nomothetically). In addition, some study designs may call for collection of separate idiographic and nomothetic data, but for complementary purposes. Integrated research designs that blend nomothetic and idiographic are a good match for certain implementation studies. For instance, nomothetic data may allow a research team to evaluate how a group of community clinics compare on treatment adherence, attendance, or outcomes. This information can help to generate hypotheses that may be subsequently tested at the unit level. In contrast, idiographic data can help to identify what factors are impacting adherence, attendance, or outcomes in a clinic and/or test causal relations at the unit level. Additional detail – and examples – about the ways research designs may relate to nomothetic and idiographic data are provided in a preliminary taxonomy below.

A growing body of research exemplifies potential ways in which the overlap between nomothetic and idiographic assessment approaches can be leveraged surrounding implementation and intervention outcomes. For instance, studies have shown the benefit of employing instruments initially developed from a nomothetic assessment tradition in idiographic ways, such as conducting single-case studies of one unit over time [50]. Examples also exist of studies that have used instruments developed from an idiographic perspective to collect data that were ultimately evaluated nomothetically. For instance, as part of a large, community-based mental health treatment effectiveness trial for children and adolescents [51], interviews were used to determine individualized (i.e., idiographic) “top problems,” which could serve as intervention targets for participants [41]. Participants were asked to describe their symptoms in their own words, and then to rank order these problems. The resulting list of each participant’s top three problems was then routinely assessed (i.e., the Youth Top Problems assessment) throughout treatment as an indicator of treatment progress (idiographic approach). In addition, the authors applied nomothetic criteria to the Youth Top Problems, evaluating the psychometric properties of the resulting ratings (including score validity via correlations with gold standard nomothetic instruments) and, ultimately, using aggregate Youth Top Problems ratings to evaluate group outcomes in a clinical trial [51].

The discussion above is intended to highlight some of the potential benefits of combining nomothetic and idiographic approaches. Nevertheless, each carries its own set of disadvantages as well. Notably, leading nomothetic strategies often demonstrate low feasibility and practicality [52]. Instruments developed from a nomothetic tradition may be subject to proprietary rights and copyright restrictions. As a result, highly specialized or overly complicated assessment instruments may lack access or relevance within certain community settings [29]. In addition, less research has focused on the score validity of idiographic methods as compared to nomothetic, and very little research has investigated the combined use of both approaches. Thus, to maximize the potential of both nomothetic and idiographic assessment approaches in advancing implementation research, a more complete understanding of the optimal scenarios, research questions, and study designs that are conducive to each approach – or the combination of approaches – is essential.

Guidelines for integrating nomothetic and idiographic methods

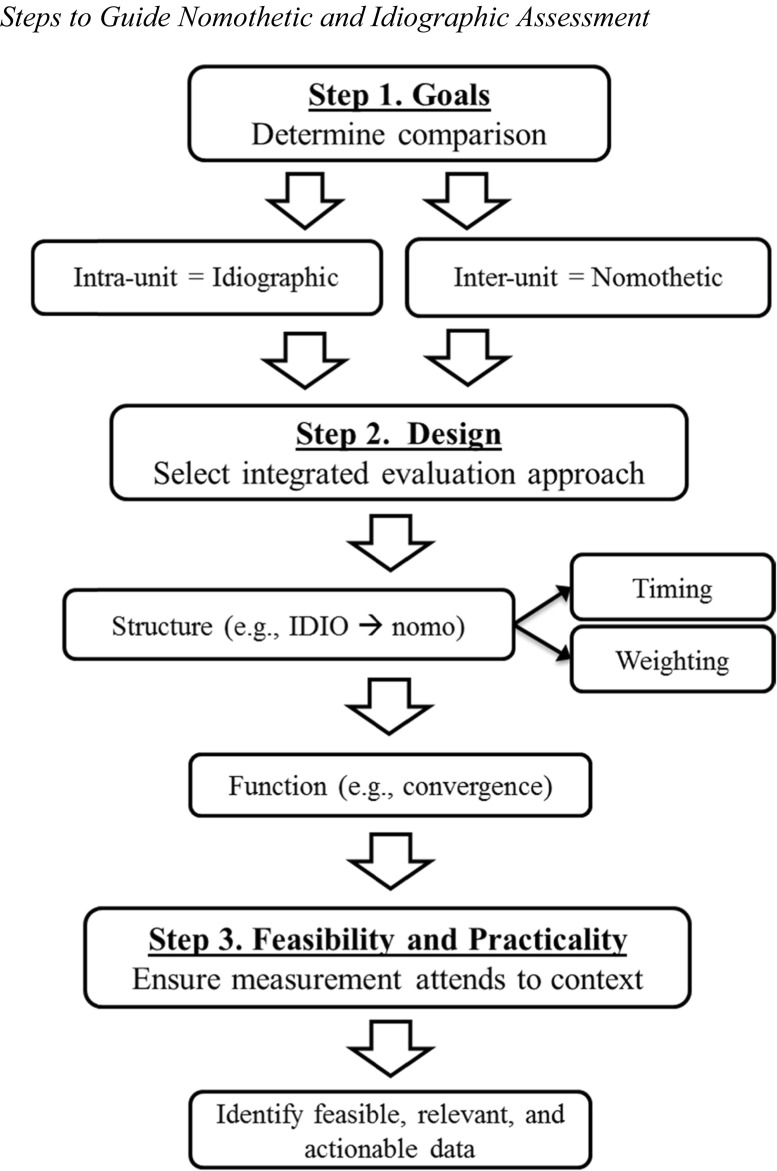

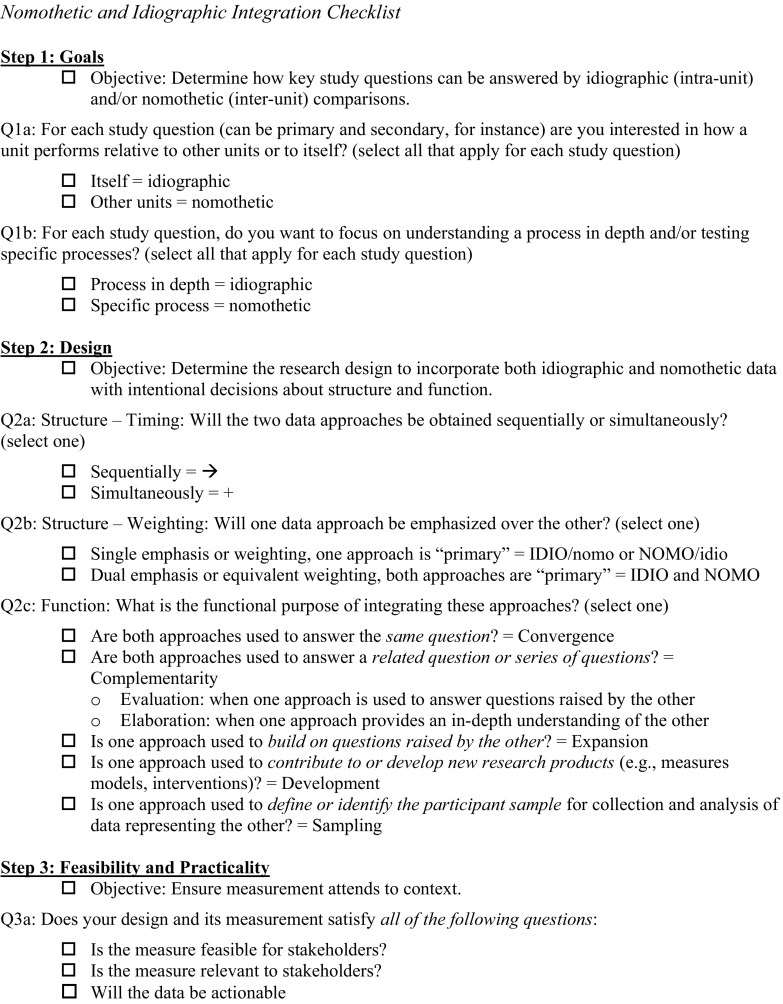

Guidelines for integrating nomothetic and idiographic measurement approaches are warranted to support their combined use in implementation research studies. We suggest a series of critical steps or decision points to guide the selection and application of nomothetic and idiographic assessment (see Figures 1 and 2). These steps include: (1) Clearly articulate study goals, (2) Select an optimal study design, and (3) Ensure the measurement approach attends to contextual constraints.

Fig. 1.

Steps to Guide Nomothetic and Idiographic Assessment

Fig. 2.

Nomothetic and Idiographic Integration Checklist Step 1: Goals Objective: Determine how key study questions can be answered by idiographic (intra-unit) and/or nomothetic (inter-unit) comparisons. Q1a: For each study question (can be primary and secondary, for instance) are you interested in how a unit performs relative to other units or to itself? (select all that apply for each study question) Itself = idiographic Other units = nomothetic Q1b: For each study question, do you want to focus on understanding a process in depth and/or testing specific processes? (select all that apply for each study question) Process in depth = idiographic Specific process = nomothetic Step 2: Design Objective: Determine the research design to incorporate both idiographic and nomothetic data with intentional decisions about structure and function. Q2a: Structure – Timing: Will the two data approaches be obtained sequentially or simultaneously? (select one) Sequentially = ➔ Simultaneously = + Q2b: Structure – Weighting: Will one data approach be emphasized over the other? (select one) Single emphasis or weighting, one approach is “primary” = IDIO/nomo or NOMO/idio Dual emphasis or equivalent weighting, both approaches are “primary” = IDIO and NOMO Q2c: Function: What is the functional purpose of integrating these approaches? (select one) Are both approaches used to answer the same question? = Convergence Are both approaches used to answer a related question or series of questions? = Complementarity Evaluation: when one approach is used to answer questions raised by the other Elaboration: when one approach provides an in-depth understanding of the other Is one approach used to build on questions raised by the other? = Expansion Is one approach used to contribute to or develop new research products (e.g., measures models, interventions)? = Development Is one approach used to define or identify the participant sample for collection and analysis of data representing the other? = Sampling Step 3: Feasibility and Practicality Objective: Ensure measurement attends to context. Q3a: Does your design and its measurement satisfy all of the following questions: Is the measure feasible for stakeholders? Is the measure relevant to stakeholders? Will the data be actionable

First, the research or evaluation objective is of paramount importance (i.e., clear articulation regarding the goals of the study), which is likely to narrow the scope of variables to those central to the investigation and reveal whether the study questions are best answered by an intra-unit (warranting an idiographic approach) or inter-unit (warranting a nomothetic approach) measurement process. At this step, researchers should ask themselves if they are most interested in how a unit performs relative to other units (nomothetic) or itself (idiographic), and whether they want to focus on understanding how a process unfolds for a particular unit over time or contexts (idiographic) versus understanding how a unit compares to other units on a particular construct (e.g., comparing settings of interest to other settings; nomothetic). Without a priori articulation of the uses and implications of the data obtained, measurement determinations cannot be specified.

Second, the optimal design to address the research question should be selected. For instance, observational studies are common in implementation science – and often preferred by community stakeholders – given the relatively frequent opportunity to evaluate a naturalistic implementation and the infrequent opportunity to randomly assign providers or sites to different conditions [6, 7]. A naturalistic, observational design may call for idiographic approaches whereas a randomized trial with design controls may be better suited for nomothetic approaches. Furthermore, attention to the timing of assessments, weighting of one assessment approach relative to another, and functional purpose (each of these is discussed further below) is critical. Even within observational designs, there are opportunities for a project to be cross-sectional and likely nomothetic (e.g., to determine the presence and level of implementation barriers and facilitators, relative to norms) or longitudinal and likely idiographic (e.g., to track changes in fidelity or other implementation outcomes over time). When combining idiographic and nomothetic approaches in a single study, selection of a design should include consideration of these structural and functional elements of that integration (see Figure 2 and below).

Third, and related to the second factor, given that the “real world” serves as the laboratory for implementation science and that evaluation measures have the potential to inform practical implementation efforts, feasible, locally relevant, and actionable assessment approaches should be considered a top priority [29]. These study considerations have clear implications for using nomothetic and/or idiographic approaches. For example, if electronic health records house patient-centered progress data, an idiographic approach may be preferred (compared to implementing a nomothetic approach) in a research study focused on providing feasible, actionable, and real-time feedback to clinicians about patient progress. Unless the goals of the study (per the first factor, above) truly necessitate using data for prediction or classification, the practical advantage of using idiographic data already on hand is likely preferred. To offer additional specific direction in this area, we adapt an existing taxonomy below to guide the combination of nomothetic and idiographic approaches.

Use of an existing taxonomy to inform integration

Guidelines for the integration of nomothetic and idiographic assessment approaches, based on study design, can also be informed by established taxonomies for integrating different types of data in implementation science. For instance, designs that mix quantitative and qualitative methodologies have been highlighted as robust research approaches that yield more powerful and higher quality results compared to either method alone [53, 54]. Although the current paper is focused on two distinct quantitative assessment approaches, we contend that frameworks for thinking about mixed methods research are useful in the extent to which they can guide the intention and systematic integration of any disparate methodologies that produce unique types of data. Similar to the considerations highlighted above, best practices in mixed methods research involve sound conceptual planning to fit the needs of the research question and study design, with purposeful collaboration among scientists from each methodological tradition and a clear acknowledgment of philosophical differences in each approach [53, 54]. Palinkas et al. [55] proposed a taxonomy for research designs that integrate qualitative and quantitative data in implementation science. They proposed three elements of mixed methods that may also be considered when integrating nomothetic and idiographic assessment approaches: structure, function, and process. Structure refers to the timing and weighting of the two approaches, function to the relationship between the questions each method is intended to answer (i.e., the same question versus different questions), and process to the ways in which different datasets are linked or combined. In all, seven structural arrangements, five functions of mixed methods, and three processes for linking quantitative and qualitative data emerged.

Although nomothetic and idiographic approaches are quantitative, the elements articulated in the mixed methods taxonomy proposed by Palinkas and colleagues can help guide their integration. Consistent with the objectives of a taxonomy, this approach is intended to organize research designs, provide clear examples, promote their use in the future, offer a pedagogical tool, and establish a common language for the design variations within implementation science [56]. Once research goals are set and design options considered, mixing nomothetic and idiographic approaches according to structure and function can optimize project evaluation. Because nomothetic and idiographic data are both represented quantitatively, the dimension of process (i.e., the ways datasets are linked or combined) is less relevant. It has therefore been omitted below.

Table 1 provides an overview of a preliminary application of the taxonomy to nomothetic (“NOMO”) and idiographic (“IDIO”) measurement approaches. As outlined by Palinkas et al. [55], the structure of design decisions illustrated in this table vary based on the timing and weighting (or emphasis) of each approach. Timing is represented by the “➔” and “+” symbols. When the timing of the two approaches is sequential, such that one is conducted prior to the other, this is indicated by the “➔” symbol, often reflecting that the first measurement approach informed the selection, execution, or interpretation of the second. When the timing of the two approaches is concurrent, this is indicated by the “+” symbol. Weighting or emphasis is indicated by capitalization, with the primary method indicated by capital letters (e.g., “IDIO” or “NOMO”). In application, it may be challenging to identify whether IDIO or NOMO is emphasized in studies that purposefully integrate both. Although authors rarely make this distinction explicitly, the weighting or emphasis is most often aligned with whichever approach reflects the “primary” research question. Nevertheless, this decision is frequently an arbitrary one that falls to the investigative team and their interpretation of study priorities and, when authors are unclear, this task then falls to the reader. Indeed, in our review of studies in the next section (Table 1), determinations about weighting were made by our team out of necessity, based on information reported in the published studies. The researcher is also cautioned against conceptualizing this as a distinction between proximal (as “primary”) and distal (as “secondary”) outcomes. A distal outcome, such as patient morbidity, may in fact answer a critical primary research question such as the effectiveness of an initiative designed to implement an evidence-based health intervention for a particular disease state. Despite some subjectivity, weighting offers a useful common language to communicate and discuss critical aspects of study design.

Table 1.

Adapted Taxonomy for Idiographic and Nomothetic Integration

| Element | Category | Definition* | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure | IDIO ➔ nomo | Sequential collection and analysis of data for idio and nomo use, beginning with idio use of data for the primary purpose of (IDIO) intra-unit comparison across contexts and time. | See text for example |

| idio ➔ NOMO | Sequential collection and analysis of data for idio and nomo use, beginning with idio use of data for the primary purpose of (NOMO) inter-unit comparison to aggregate data for classification or prediction. | [57] | |

| nomo ➔ IDIO | Sequential collection and analysis of data for idio and nomo use, beginning with nomo use of data for the primary purpose of (IDIO) intra-unit comparison across contexts and time. | [58] | |

| NOMO ➔ idio | Sequential collection and analysis of data for idio and nomo use, beginning with nomo use of data for the primary purpose of (NOMO) inter-unit comparison to aggregate data for classification or prediction. | [34] | |

| idio + NOMO | Simultaneous collection and analysis of data for idio and nomo use, for the primary purpose of (NOMO) inter-unit comparison to aggregate data for classification or prediction. | [59] | |

| IDIO + nomo | Simultaneous collection and analysis of data for primary purpose of (IDIO) intra-unit comparison across contexts and time. | [60] | |

| NOMO + IDIO | Simultaneous collection and analysis of data for idio and nomo use, giving equal weight to both approaches | [61] | |

| Function | Convergence | Using both idio and nomo approaches to answer the same question, either through comparison of results to see if they reach the same conclusion (triangulation) or by converting a data set from one use into another (e.g. data collected for idio purpose being used nomothetically or vice versa) | [60] |

| Complementarity | Using each approach to answer a related question or series of questions for purposes of evaluation (e.g., using data for nomo use to answer individual idio questions or vice versa) or elaboration (e.g., using idio data to provide depth of understanding and nomo data to provide breadth of understanding) |

Elaboration example: [59] |

|

| Expansion | Using one approach to answer questions raised by the other (e.g., using dataset for idio use to explain results from data for nomo use) | [60] | |

| Development | Using one approach to answer questions that will enable use of the other to answer other questions (e.g., develop data collection measures, conceptual models or interventions) | See text for example | |

| Sampling | Using one approach to define or identify the participant sample for collection and analysis of data representing the other (e.g., selecting interview informants based on responses to survey questionnaire) | [58] |

*Note. The overarching categories and the specific definitions for the taxonomy are directly from Palinkas et al. [55]. Minor adaptations were made to translate the quantitative/qualitative integration to the current idiographic/nomothetic integration. Process was omitted above because all data are quantitative and thus relatively easily integrated

Examples of idiographic/nomothetic integration

The literature reflecting integrated idiographic and nomothetic measurement approaches in implementation is limited and focused on implementation and intervention outcomes, so we identified study design examples from both implementation science and health services research that (1) use data for idiographic and nomothetic purposes and (2) appear to represent one or more of the structural and functional categories outlined in Table 1. Rather than conduct a comprehensive literature review, we searched the literature for illustrative examples of the seven structures and five functions [[55]]. Below, each structural and functional category is presented with an example from the literature and/or hypothetical examples relevant to implementation research. The examples demonstrate the value added to study goals, design, and practicality when using an idiographic and nomothetic approach to assessment in an integrated research design.

Structure

The seven structural categories are defined based on the timing and weighting of nomothetic and idiographic data in an integrated design. The first four structures presented represent sequential (“ ➔”) data collection, and the last three represent simultaneous (“+”) data collection.

IDIO ➔ nomo

The first structural category in Table 1 is IDIO ➔ nomo, in which a study design begins with the primary purpose of intra-unit comparison across contexts or time (IDIO). For instance, a hospital may examine an individual clinic or department performance indicator (e.g., no show rate, wait times, and/or 30-day readmission rates) across time (e.g., one fiscal year to the next). The primary idiographic (IDIO) goal of using these intra-unit data could be to identify longitudinal patterns of clinic or department performance over time as well as factors that influence performance for the particular clinic or department (e.g., time of year, type of patient). A secondary nomothetic goal may be to compare performance across clinics or departments to hospital norms or national performance standards to help determine if a particular clinic should be more closely examined for their performance strengths or needs.

Idio ➔ NOMO

The next structural category, idio ➔ NOMO, also seeks to collect data for idiographic purposes initially, followed by a nomothetic approach, but the primary purpose is for nomothetic classification or prediction (NOMO). Hirsch and colleagues’ [57] work offers a possible example of using data both idiographically and nomothetically for patients in primary care experiencing lower back pain. The idiographic data were patient self-reported pain intensity and a visual analog measure of health. Emotional and physical symptoms measured by several standardized symptom checklists were intended to yield data used for nomothetic comparison to other patients. A cluster analysis was performed with these variables, which identified four groups that were used to classify patients and predict health care utilization and costs. However, it could also be argued that, because both approaches were actually used to determine patient groups, a more specific subcategory (e.g., [idio + nomo] ➔ NOMO) might be an even more accurate classification. Importantly, Hirsch and colleagues selected a design and analyses to account for both intra- and inter-client variations to classify patients and predict the outcome of interest for patient groups.

Nomo ➔ IDIO

Lambert and colleagues [58] provide an example of nomo ➔ IDIO structure in which the nomothetic approach precedes an idiographic approach, for a primarily IDIO purpose. They collected the Outcome Questionnaire-45 (OQ-45) from all patients to classify and predict individual patient progress in psychosocial treatment based on established normative clinical cutoffs. This nomothetic approach was used to identify “signal-alarm cases” (i.e., individual patients at risk of poor treatment response, based on their OQ-45 score). For these at-risk cases that were selected, intensive individual progress monitoring over time (IDIO data collection) was initiated to maximize individual patient outcomes. The authors recommend that individual patient data be used for feedback systems to therapists in routine care to support case level progress monitoring and treatment planning.

NOMO ➔ idio

In a NOMO ➔ idio structure, a primary nomothetic approach is followed by a secondary idiographic approach. Coomber and Barriball [34] conducted a systematic literature review on a research question that reflects this structure. They sought to understand how specific independent variables designed for nomothetic use (e.g., standardized instruments of job satisfaction, work quality, professional commitment, work stress) predict subsequent intra-unit dependent variables over time (e.g., individual employee intent to leave or stay, and actual decisions thereof) among hospital-based nurses. The authors concluded that the studies reviewed used primarily nomothetic approaches and were frequently underspecified for the purpose of understanding and supporting individual intentions and decisions at the nurse or nursing ward level. These findings reflect conclusions from our literature search, in which NOMO ➔ idio studies were rare. However, a study seeking to answer this question could use a design whereby a standardized instrument of work stress is collected across nurses and nursing sites to help predict turnover rates. This primary nomothetic approach would yield cross-site findings about the distribution and norms of work stress within the sample. These primarily “NOMO” findings could also inform an idiographic approach to track individual nurses’ work stress levels over time and/or across work contexts based on individually tailored stress management interventions.

Idio + NOMO

This structure of idio + NOMO is the first of three structures listed in Table 1 that reflect simultaneous (“+”) collection and analysis of data, instead of a sequential data collection (“➔” above). This design structure (idio + NOMO) is for the primary purpose of comparing scores to aggregate data for classification or prediction (NOMO). This is illustrated in a study by Fisher, Newman, and Monenaar [59] where the primary focus was on analyzing treatment outcome for the entire sample of patients. However, this was accomplished by aggregating individual patterns over time (e.g., “idio” daily diary ratings) in a dataset to examine treatment outcome for the overall patient sample. Thus, the main emphasis was on nomothetic prediction but derived from a approach originally designed to produce idiographic data (idio + NOMO). Moreover, findings indicated that the contribution of individual (idiographic) pattern variability of diary ratings significantly moderated the effect of time in treatment on NOMO-measured treatment outcomes.

IDIO + nomo

Simultaneous collection and analysis of idiographic nomothetic data for the primary purpose of exploration, hypothesis generation, or intra-unit analysis is represented by the IDIO + nomo structure. Sheu, Chae, and Yang [60] offer an example of how idiographic and nomothetic approaches can be simultaneously combined to understand implementation of an information management system (called “ERP”), wherein the countries (or sites) are regarded as the individual unit. They simultaneously collected secondary data from a literature review on multinational implementation of ERP (nomo) as well as case research from six companies in different countries involved in ERP implementation (IDIO) to understand how individual countries’ (IDIO) differences impact implementation. The design included idiographic case research to systematically study individualized strategies based on time since implementation as well as similarities and differences in implementation between different units (countries). Results informed the identification of local, individualized (idiographic) characteristics that specific countries needed to consider (e.g., language, culture, politics, governmental regulations, management style and labor skills) to support decision making about adoption/implementation of the information system (IDIO + nomo).

Nomo + IDIO

The last structural category, NOMO + IDIO, describes a research design whereby data are simultaneously collected to inform intra-unit and inter-unit study goals, which are equally prioritized. For instance, Wandner et al. [61] examined the effect of a perspective-taking intervention on pain assessment and treatment decisions at the intra-unit level across time (IDIO) and inter-unit level (NOMO). The research team collected a participant pain assessment and treatment ratings on a scale of 1 to 10 and the GRAPE questionnaire to assess pain decisions based on sex, race, and age. These data were used for nomothetic and idiographic application. For instance, aggregate data were examined between perspective taking and control groups for the purpose of predicting change over time (NOMO goal for inter-unit comparison, prediction). Also, individual participant decision-making policies based on their individual weighting of different contextual cues was examined to understand IDIO patterns and variability of patient decisions. Consistent with the goals of their study, combining these approaches facilitated empirical investigation of idiographic participant variation across context as well as classifying nomothetic implementation outcomes of a perspective taking intervention.

Function

Drawing from Palinkas’ et al. [55] framework, we have identified five functional purposes for designing an implementation research study to incorporate both idiographic and nomothetic approaches to using data. These include Convergence, Complementarity, Expansion, Development, and Sampling. For each function below, one of the aforementioned studies and/or hypothetical examples is referenced for the function(s) they illustrate.

Convergence

Convergence represents the use of both approaches to answer the same question. This may be through comparison of results to determine whether the same conclusion is reached (i.e., triangulation) or by converting a dataset from one type into another (e.g., data originally intended for idiographic use being used nomothetically or vice versa). The Sheu, Chae, and Yang [60] article provides an example of triangulating both case research (idio) and secondary literature review (nomo) to identify specific factors that influence the implementation of information management systems at the national level.

Complementarity

This function is carried out when each approach is used to answer a related question or series of questions. This may be for evaluation (when one approach is used to answer questions raised by the other), or elaboration (when one approach provides an in-depth understanding of the other). An example of an evaluation function might be a study that initially uses individual clinic or department performance data over time to study idiographic trends. Those trends may raise subsequent questions about how the clinics’ data compare to national standards, and the investigator could then use national health care performance standards (nomothetic approach) as benchmarks to evaluate those clinics’ performance. As an example of elaboration within the complementarity function, Fisher, Newman, and Monenaar [59] found that intra-unit variability (idio) among patients complemented their understanding of inter-unit (nomo) outcomes for the entire sample. That is, the amount of variance in individual patient patterns over time significantly moderated the effect of time in treatment on the reliable increase of nomothetic (inter-unit) outcomes (Table 1).

Expansion

Similar to complementarity, a design with the expansion function uses one approach to answer questions raised by the other. However, instead of using idiographic and nomothetic approaches to complement the same research question (i.e., complementarity), these designs build upon one another in a distinct, stepwise fashion. For instance, the Sheu, Chae, and Yang [60] study not only represents the convergence function (noted above), but also illustrates expansion. Their case study approach to understanding implementation challenges in each nation (idio) was selected to build upon and provide new information about existing literature on multinational implementation across countries (nomo).

Development

Development is another function whereby one approach is used to answer questions that were raised by another approach. Development is distinguished from complementarity and expansion by an intention to contribute to or develop new research products. General examples include the development of data collection measures, conceptual models or interventions. In an implementation context, to borrow from the topic studied by Coomber and Barriball [34], idiographic change over time or context (e.g., nurse stress level self-reports across multiple intervals or nursing units) is likely to inform the development of standardized instruments for nomothetic classification or prediction (e.g., nurse professional wellness) as well as tailored interventions (e.g., organizational supports, administrative practices).

Sampling

The function of an integrated design is sampling when one approach is used to define or identify the participant sample for collection and analysis of data representing the other. A general example would be selecting interview informants (idiographic) based on responses to survey questionnaires (nomothetic). The function of the Lambert and colleagues [58] study appears to be sampling, given that OQ-45 data were used in nomothetic fashion to identify patients within a clinical sample who are predicted to have poor treatment outcome. The identification of this sub-sample of at-risk patients was followed by an individual progress monitoring plan over time (idiographic) to serve individuals at risk. Lambert and colleagues [54] is also an example of convergence, as data were initially collected for nomothetic purposes subsequently converted for idiographic use (i.e., intra-unit treatment planning).

Summary and future directions

This paper is intended to advance a practical and rigorous measurement agenda in implementation science by providing guidance on the combination of previously disparate assessment traditions. Specifically, we argue for strategic and intentional integration of idiographic and nomothetic assessment approaches in a manner that addresses project goals and aligns with study design. The benefits of such integration include simultaneously enhancing the rigor and relevance of assessments across multiple levels within service systems.

Importantly, although particular instruments may have been developed with a nomothetic or idiographic tradition or purpose in mind, we conceptualize the primary distinction between the two as the manner in which the data are interpreted or used. Despite this, the line between nomothetic and idiographic approaches is inherently blurry, and is sometimes influenced by the perspective of the research team in addition to the relations among study variables. To guide the integration of idiographic and nomothetic assessment, we presented a preliminary framework – adapted from the taxonomy proposed by Palinkas et al. [55] – to detail different structural and functional arrangements. In addition, we presented a set of tools (Figures 1 and 2) to facilitate application of the framework.

When available, published studies that exemplify research designs with an integrated nomothetic and idiographic approach were presented. However, our review of the literature revealed a paucity of such integrated designs. Thus, hypothetical examples were offered as needed to clarify the potential of each category to support integrated implementation research designs. Among those identified, the simultaneous versus sequential collection of data is not readily apparent, making the purpose of an integrated design underspecified in many published studies. Moreover, four of the seven studies included as illustrations of structural categories contained sufficient detail to also categorize the function of integration. Two of these [52, 60] appeared to use an integrated idiographic/nomothetic design for more than one function. Investigators of future studies designed to incorporate both idiographic and nomothetic use of data are thus encouraged to detail the functional purpose(s) of using both approaches.

Future research may include a systematic review of implementation research studies that leverages nomothetic and idiographic approaches to evaluate the frequency with which each structural and functional category appears. For instance, it may be that there are certain structures/functions – potentially the idiographic use of nomothetic data (e.g., NOMO ➔ idio) – that occur more commonly. Further, the relationships between each category and other study characteristics should be examined. Relevant study characteristics may include the research context or setting, phase of implementation examined (e.g., Exploration, Adoption, Implementation, Sustainment; [31]), levels at which data were collected (e.g., inner context, outer context, individual), and overall complexity of study design. Consistent with the findings from Palinkas et al. [51] in their examination of mixed methods approaches, it may be that the outer context is also underrepresented in the literature.

Individual studies can contribute to the advancement of an integrated assessment agenda by more explicitly detailing their use of – and rationale for – combined idiographic and nomothetic approaches. Among other things, this would include the identification of whether one approach is primary, one secondary, or whether the approaches were equivalently weighted. In addition, specifying whether the sequential or simultaneous data collection occurred within the study design would also support a transparent explanation of the structure (and ultimately, function) of integrating idiographic and nomothetic approaches. This would be pivotal in reducing the ambiguity and subjectivity noted above when classifying published work. Also, for the purpose of advancing scientific knowledge within the implementation literature, more explicit description of assessment use and rationale in the context of the study goals and design would support the replication and expansion of individual study designs and findings.

Finally, an integrated assessment agenda may also align with increased attention to pragmatic research within implementation science, as it emphasizes incorporation of the local context and stakeholder perspectives into research design with the goal of accelerating and broadening its impact on policy and practice [9, 10]. The collection of stakeholder input about the ways in which different assessment methods align with their needs, expectations, and values is likely to enhance pragmatic assessment [62]. Within this frame, it could be hypothesized that patients and practitioners may place greater value on data from idiographic methods whereas policymakers may disproportionately value data from nomothetic methods. Indeed, recent work in the area of education sector mental health has supported the notion that clinicians [63, 64] and service recipients [65] prefer the flexibility and personalization associated with the idiographic approach. Despite this, additional work is needed that examines ways to optimize assessments that leverage the best qualities of both approaches. In a prime example of this, members of the Society for Implementation Research Collaboration (SIRC [66]) currently have a large, federally funded project underway in the United States to develop pragmatic instruments of key implementation outcomes (acceptability, feasibility, and appropriateness; [29]). The process includes structured stakeholder input and an explicit objective to create psychometrically strong, low-burden instruments, and may serve as a generalizable example for the integration of idiographic and nomothetic approaches. It is our perspective that such deliberate, pragmatic initiatives represent the future of implementation science as the field strives to balance rigor and relevance and promote large-scale impact in service systems.

Compliance with ethical standards

Information/findings not previously published

Although no original data are presented in the current manuscript, the information contained in the manuscript has not been published previously is not under review at any other publication.

Statement on any previous reporting of data

None of the information contained in the current manuscript has been previously published.

Statement indicating that the authors have full control of all primary data and that they agree to allow the journal to review their data if requested

Not applicable. No data are presented in the manuscript.

Statement indicating all study funding sources

This publication was supported in part by grant K08 MH095939 (Lyon), awarded from the National Institute of Mental Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Statements indicating any actual or potential conflicts of interest

No conflicts of interest.

Statement on human rights

Not applicable. No data were collected from individuals for the submitted manuscript.

Statement on the welfare of animals

Not applicable. No data were collected from animals for the submitted manuscript.

Informed consent statement

Not applicable.

Helsinki or comparable standard statement

Not applicable.

IRB approval

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Implications

Research: Implementation research studies should be designed with the intentional integration of idiographic and nomothetic approaches for specifically-stated functional purposes (i.e., Convergence, Complementarity, Expansion, Development, Sampling).

Practice: Implementation intermediaries (e.g., consultants or support personnel) and health care professionals (e.g., administrators or service providers) are encouraged to track (1) employee and organizational factors (e.g., implementation climate), (2) implementation processes and outcomes (e.g., adoption), and (3) individual and aggregate service outcomes using both idiographic (comparing within organizations or individuals) and nomothetic (comparing to standardized benchmarks) approaches when monitoring intervention implementation.

Policy: The intentional collection and integration of idiographic and nomothetic assessment approaches in implementation science is likely to result in data-driven policy decisions that are more comprehensive, pragmatic, and relevant to stakeholder concerns than either alone.

References

- 1.Eccles MP, Mittman BS. Welcome to Implementation Science. Implement Sci. 2006;1:1. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-1-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khoury MJ, Gwinn M, Yoon PW, Dowling N, Moore CA, Bradley L. The continuum of translation research in genomic medicine: how can we accelerate the appropriate integration of human genome discoveries into health care and disease prevention? Genet Med. 2007;9:665–674. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31815699d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauer MS, Damschroder L, Hagedorn H, Smith J, Kilbourne AM. An introduction to implementation science for the non-specialist. BMC Psychol. 2015;3:32. doi: 10.1186/s40359-015-0089-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, Griffey R, Hensley M. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Admin Pol Ment Health. 2011;38:65–76. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, Damschroder LJ, Smith JL, Matthieu MM, Proctor EK, Kirchner JE. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the expert recommendations for implementing change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. 2015;10:21. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown CH, Curran G, Palinkas LA, Aarons GA, Wells KB, Jones L, Collins LM, Duan N, Mittman BS, Wallace A, Tabak RG, Ducharme L, Chambers D, Neta G, Wiley T, Landsverk J, Cheung K, Cruden G: An overview of research and evaluation designs for dissemination and implementation. Annu Rev Public Health 2016, 38:null. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Landsverk J, Brown CH, Reutz JR, Palinkas L, Horwitz SM. Design elements in implementation research: a structured review of child welfare and child mental health studies. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res. 2010;38:54–63. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0315-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mercer SL, DeVinney BJ, Fine LJ, Green LW, Dougherty D. Study designs for effectiveness and translation research. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33:139–154. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glasgow RE. What does it mean to be pragmatic? Pragmatic methods, measures, and models to facilitate research translation. Health Educ Behav. 2013;40:257–265. doi: 10.1177/1090198113486805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krist AH, Glenn BA, Glasgow RE, Balasubramanian BA, Chambers DA, Fernandez ME, Heurtin-Roberts S, Kessler R, Ory MG, Phillips SM, Ritzwoller DP, Roby DH, Rodriguez HP, Sabo RT, Gorin SNS, Stange KC, Group TMS Designing a valid randomized pragmatic primary care implementation trial: the my own health report (MOHR) project. Implement Sci. 2013;8:1–13. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Behn RD. Why measure performance? Different purposes require different measures. Public Adm Rev. 2003;63:586–606. doi: 10.1111/1540-6210.00322. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee RG, Dale BG. Business process management: a review and evaluation. Bus Process Manag J. 1998;4:214–225. doi: 10.1108/14637159810224322. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGlynn EA. There is no perfect health system. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004;23:100–102. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.3.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castrucci BC, Rhoades EK, Leider JP, Hearne S. What gets measured gets done: an assessment of local data uses and needs in large urban health departments. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2015;21(Suppl 1):S38–S48. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ijaz K, Kasowski E, Arthur RR, Angulo FJ, Dowell SF. International health regulations–what gets measured gets done. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18:1054–1057. doi: 10.3201/eid1807.120487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herman KC, Riley-Tillman TC, Reinke WM. The role of assessment in a prevention science framework. Sch Psychol Rev. 2012;41:306–314. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fuchs D, Fuchs LS. Introduction to response to intervention: what, why, and how valid is it? Read Res Q. 2006;41:93–99. doi: 10.1598/RRQ.41.1.4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKay R, Coombs T, Duerden D. The art and science of using routine outcome measurement in mental health benchmarking. Australas Psychiatry. 2014;22:13–18. doi: 10.1177/1039856213511673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thacker SB. Public health surveillance and the prevention of injuries in sports: what gets measured gets done. J Athl Train. 2007;42:171–173. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lefkowith D. What gets measured gets done: turning strategic plans into real world results. Manag Q. 2001;42:20–24. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woodard JR. What gets measured, gets done! Agric Educ Mag. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trivedi P. Improving government performance: what gets measured, gets done. Econ Polit Wkly. 1994;29:M109–M114. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Proctor EK, Landsverk J, Aarons G, Chambers D, Glisson C, Mittman B. Implementation research in mental health services: an emerging science with conceptual, methodological, and training challenges. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res. 2009;36:24–34. doi: 10.1007/s10488-008-0197-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carlier IVE, Meuldijk D, Van Vliet IM, Van Fenema E, Van der Wee NJA, Zitman FG. Routine outcome monitoring and feedback on physical or mental health status: evidence and theory. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18:104–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harding KJK, Rush AJ, Arbuckle M, Trivedi MH, Pincus HA. Measurement-based care in psychiatric practice: a policy framework for implementation. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72:1–478. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10r06282whi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trivedi MH, Daly EJ. Measurement-based care for refractory depression: a clinical decision support model for clinical research and practice. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88:S61–S71. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hollingsworth B. The measurement of efficiency and productivity of health care delivery. Health Econ. 2008;17:1107–1128. doi: 10.1002/hec.1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoagwood KE, Jensen PS, Acri MC, Serene Olin S, Eric Lewandowski R, Herman RJ. Outcome domains in child mental health research since 1996: have they changed and why does it matter? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51:1241–1260. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lewis CC, Stanick CF, Martinez RG, Weiner BJ, Kim M, Barwick M, Comtois KA. The Society for Implementation Research Collaboration Instrument Review Project: a methodology to promote rigorous evaluation. Implement Sci. 2015;10:1–18. doi: 10.1186/s13012-014-0195-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rabin BA, Purcell P, Naveed S, Moser RP, Henton MD, Proctor EK, Brownson RC, Glasgow RE. Advancing the application, quality and harmonization of implementation science measures. Implement Sci. 2012;7:119. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aarons GA, Hurlburt M, Horwitz SM. Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res. 2011;38:4–23. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA. Lowery JC, others: fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martinez RG, Lewis CC, Weiner BJ. Instrumentation issues in implementation science. Implement Sci. 2014;9:118. doi: 10.1186/s13012-014-0118-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coomber B, Louise Barriball K. Impact of job satisfaction components on intent to leave and turnover for hospital-based nurses: a review of the research literature. Int J Nurs Stud. 2007;44:297–314. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Novick MR. The axioms and principal results of classical test theory. J Math Psychol. 1966;3:1–18. doi: 10.1016/0022-2496(66)90002-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cone, J. D. (1986). Idiographic, nomothetic, and related perspectives in behavioral assessment. In Conceptual foundations of behavioral assessment, 111–128.

- 37.Glisson C, Landsverk J, Schoenwald S, Kelleher K, Hoagwood KE, Mayberg S, Green P. Health TRN on YM: assessing the organizational social context (OSC) of mental health services: implications for research and practice. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res. 2008;35:98–113. doi: 10.1007/s10488-007-0148-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kilbourne, A. M., Almirall, D., Eisenberg, D., Waxmonsky, J., Goodrich, D., Fortney, J., Kirchner, J. E., Solberg, L., Main, D., Bauer, M. S., Kyle, J., Murphy, S., Nord, K., & Thomas, M. (2014). Protocol: adaptive implementation of effective programs trial (ADEPT): cluster randomized SMART trial comparing a standard versus enhanced implementation strategy to improve outcomes of a mood disorders program. Implement Sci, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Lochman JE, Boxmeyer C, Powell N, Qu L, Wells K, Windle M. Dissemination of the coping power program: importance of intensity of counselor training. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77:397–409. doi: 10.1037/a0014514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Self-Brown S, Valente JR, Wild RC, Whitaker DJ, Galanter R, Dorsey S, Stanley J. Utilizing benchmarking to study the effectiveness of parent–child interaction therapy implemented in a community setting. J Child Fam Stud. 2012;21:1041–1049. doi: 10.1007/s10826-012-9566-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weisz JR, Chorpita BF, Frye A, Ng MY, Lau N, Bearman SK, Ugueto AM, Langer DA, Hoagwood KE. Youth top problems: using idiographic, consumer-guided assessment to identify treatment needs and to track change during psychotherapy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;79:369–380. doi: 10.1037/a0023307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Biglan A, Ary D, Wagenaar AC. The value of interrupted time-series experiments for community intervention research. Prev Sci. 2000;1:31–49. doi: 10.1023/A:1010024016308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cronbach L, Gleser G, Nanda H, Rajaratnam N: The Dependability of Behavioral Measurements: Theory of Generalizability for Scores and Profiles. John Wiley & Sons; 1972.

- 44.Barrios B, Hartman DP: THe contributions of traditional assessment: Concepts, issues, and methodologies. In Conceptual foundations of behavioral assessment. New York, NY: Guilford; 1986.

- 45.Foster SL, Cone JD. Validity issues in clinical assessment. Psychol Assess. 1995;7:248–260. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.7.3.248. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mash EJ, Hunsley J. Commentary: evidence-based assessment—strength in numbers. J Pediatr Psychol. 2008;33:981–982. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm140. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McLeod BD, Jensen-Doss A, Ollendick TH: Overview of diagnostic and behavioral assessment. In Diagnostic and behavioral assessment in children and adolescents: A clinical guide. Edited by McLeod BD, Jensen-Doss A, Ollendick TH, McLeod BD (Ed), Jensen-Doss A (Ed), Ollendick TH (Ed). New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 2013:3–33.

- 48.Biglan A: Changing Cultural Practices: A Contextualist Framework for Intervention Research. Reno, NV, US: Context Press; 1995.

- 49.Jaccard J, Dittus P: Idiographic and nomothetic perspectives on research methods and data analysis. In Research methods in personality and social psychology. 11th edition.; 1990:312–351.

- 50.Vlaeyen JWS, de Jong J, Geilen M, Heuts PHTG, van Breukelen G. Graded exposure in vivo in the treatment of pain-related fear: a replicated single-case experimental design in four patients with chronic low back pain. Behav Res Ther. 2001;39:151–166. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(99)00174-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weisz JR, Chorpita BF, Palinkas LA, Schoenwald SK, Miranda J, Bearman SK, Daleiden EL, Ugueto AM, Ho A, Martin J, Gray J, Alleyne A, Langer DA, Southam-Gerow MA, Gibbons RD: Testing standard and modular designs for psychotherapy treating depression, anxiety, and conduct problems in youth: A randomized effectiveness trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Elliott R, Wagner J. D M, Rodgers B, Alves P, Café MJ: psychometrics of the personal questionnaire: a client-generated outcome measure. Psychol Assess. 2016;28:263–278. doi: 10.1037/pas0000174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Creswell JW, Klassen AC, Clark VLP, Smith KC: Best Practices for Mixed Methods Research in the Health Sciences. .

- 54.Robins CS. Ware NC, dosReis S, Willging CE, Chung JY, Lewis-Fernandez R: dialogues on mixed-methods and mental health services research: anticipating challenges, building solutions. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59:727–731. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.7.727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Chamberlain P, Hurlburt MS, Landsverk J. Mixed-methods designs in mental health services research: a review. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62:255–263. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.3.pss6203_0255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Teddlie C, Tashakkori A., Major issues and controversies in the use of mixed methods in the social and behavioral sciences. In Handbook of mixed methods in social &behavioral research. SAGE; 2003:3–50.

- 57.Hirsch O, Strauch K, Held H, Redaelli M, Chenot J-F, Leonhardt C, Keller S, Baum E, Pfingsten M, Hildebrandt J, Basler H-D, Kochen MM, Donner-Banzhoff N, Becker A. Low back pain patient subgroups in primary care: pain characteristics, psychosocial determinants, and health care utilization. Clin J Pain. 2014;30:1023–1032. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lambert MJ, Harmon C, Slade K, Whipple JL, Hawkins EJ. Providing feedback to psychotherapists on their patients’ progress: clinical results and practice suggestions. J Clin Psychol. 2005;61:165–174. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fisher AJ, Newman MG. M C: a quantitative method for the analysis of nomothetic relationships between idiographic structures: dynamic patterns create attractor states for sustained posttreatment change. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;79:552–563. doi: 10.1037/a0024069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sheu C, Chae B, Yang C-L. National differences and ERP implementation: issues and challenges. Omega. 2004;32:361–371. doi: 10.1016/j.omega.2004.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wandner LD, Torres CA, Bartley EJ, George SZ, Robinson ME. Effect of a perspective-taking intervention on the consideration of pain assessment and treatment decisions. J Pain Res. 2015;8:809–818. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S88033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Glasgow RE, Riley WT. Pragmatic measures: what they are and why we need them. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45:237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]