Abstract

Lay health advisor (LHA) programs have made strong contributions towards the elimination of health disparities and are increasingly being implemented to promote health and prevent disease. Developed in collaboration with African-American survivors, the National Witness Project (NWP) is an evidence-based, community-led LHA program that improves cancer screening among African-American women. NWP has been successfully disseminated, replicated, and implemented nationally in over 40 sites in 22 states in diverse community settings, reaching over 15,000 women annually. We sought to advance understanding of barriers and facilitators to the long-term implementation and sustainability of LHA programs in community settings from the viewpoint of the LHAs, as well as the broader impact of the program on African-American communities and LHAs. In the context of a mixed-methods study, in-depth telephone interviews were conducted among 76 African-American LHAs at eight NWP sites at baseline and 12–18 months later, between 2010 and 2013. Qualitative data provides insight into inner and outer contextual factors (e.g., community partnerships, site leadership, funding), implementation processes (e.g., training), as well as characteristics of the intervention (e.g., perceived need and fit in African-American community) and LHAs (e.g., motivations, burnout) that are perceived to impact the continued implementation and sustainability of NWP. Factors at the contextual levels and related to motivations of LHAs are critical to the sustainability of LHA programs. We discuss how findings are used to inform (1) the development of the LHA Sustainability Framework and (2) strategies to support the continued implementation and sustainability of evidence-based LHA interventions in community settings.

Keywords: Lay health advisors, Cancer screening, Sustainability, Implementation, Evidence-based programs, Qualitative research

There has been strong interest in “dissemination and implementation science” (D&I) to address the tremendous gap between research and practice [1–3]. Researchers have made significant advances in understanding factors influencing the initial uptake and integration of evidence-based programs [1, 3, 4]. However, much less empirical work has focused on understanding the ongoing implementation and long-term sustainability of interventions, particularly in community settings [5]. Sustainability is defined as the continued use of program components for the sustained achievement of desirable program and population outcomes [6, 7]. Experts have prioritized this understudied area, identifying it as “one of the most significant translational research problems of our time” [1, 5]. In particular, understanding which factors impact sustainability was identified as critically important by D&I experts [5]. There is tremendous value in advancing research on sustainability in community settings, since funding and public health agencies make significant investments in developing and implementing programs without an understanding of how to sustain them in the real world [8–10]. The limited research conducted in this area suggests that while funding is one important influence on sustainability [11, 12], other factors warrant further in-depth investigation including factors at the organizational level and related to characteristics of the intervention and interventionists [5, 11, 13–21].

Lay health advisor (LHA) programs are being increasingly implemented in the USA and are highly successful in promoting health and reducing health disparities for many diseases [22–24]. LHAs are trained community members who typically deliver health education, navigation, resources, and social support [23, 25]. LHA programs are based on the premise that engaging community members contributes to community empowerment and capacity-building, while also raising awareness of health and social justice issues, enhancing access to care, and improving health behaviors and outcomes [24]. Efficacy and effectiveness trials indicate that LHA programs are effective in improving health behavior change in several areas, including cancer screening, with the strongest evidence from studies with racial/ethnic minority populations [23, 26–33]. Financial investments at the state and national level are being made in the implementation of LHA programs by funding agencies and the government, without an understanding of how to sustain such programs in community-based settings [22]. This is critical to investigate, as sustainability is a substantial challenge for LHA programs [11, 34, 35], particularly in underserved communities and settings [36]. Given that most LHA research has focused on program efficacy and their impact on program attendees, little is known about the context of LHA programs in real-world settings that can inform understanding of issues that impact program implementation and sustainability [37, 38].

The National Witness Project (NWP) is an evidence-based, nationally disseminated LHA program. NWP was founded in 1990 with a group of community-based African-American breast/cervical cancer survivors to reduce cancer stigma and address disparities in knowledge, awareness, and early detection behaviors among underserved African-American women, with the ultimate goal of reducing excess cancer morbidity and mortality [39]. Historically, African-Americans have had greater medical mistrust and lower healthcare engagement and adherence rates to breast/cervical cancer screening guidelines [40]. NWP uses a theory-based, culturally appropriate model [41] that is comparable to many other community-based LHA programs. Trained African-American LHAs are primarily responsible for organizing, arranging recruitment for, and conducting 60–90 min group-based educational sessions in their communities; serving as a community resource related to cancer prevention/screening and navigation; providing social support; and making connections with community organizations [42, 43]. The program is community-led, and about half of the LHAs are African-American cancer survivors who deliver empowering testimonials and narratives and serve as “role models” [42, 44–47]. LHAs are often volunteers, though some sites provide LHAs with stipends. NWP leadership varies across sites, though program directors or staff typically help coordinate operations (LHA recruitment, training), provide leadership, and secure funding. Each program operates fairly independently, though national leadership provides some support and communication through newsletters, emails, conference calls, and technical support when possible. Consistent with many community-based LHA programs [48], the organizational base of NWP sites includes a range of institutions: non-profit organizations (e.g., YWCA, Komen), academic and medical centers, hospitals, faith-based organizations, and health departments [49]. Over the past 25 years, NWP has been disseminated, replicated, and implemented nationally at over 40 urban and rural sites across 22 states, with over 400 volunteers, reaching over 15,000 women annually [49]. NWP is highly effective in increasing breast and cervical cancer screening; a replication trial found that mammography screening rates increased by 43.3% among underserved African-American women [49]. NWP is an exemplar of sustained and effective LHA programs and has been identified as one of the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) “Research Tested Intervention Programs” [41].

This research comes from a 2-year longitudinal, mixed-methods study among eight NWP sites to understand factors that influence the long-term implementation, sustainability, and impact of this community-engaged LHA program within African-American communities [36, 50]. This paper focuses on findings from qualitative interviews among 76 LHAs from eight NWP sites at baseline and 12–18 month follow-up. This paper seeks to (1) advance understanding of barriers and facilitators to the long-term implementation and sustainability of community-engaged and community-based LHA programs, including factors that impact the participation and retention of LHAs, and (2) document the impact of LHA programs on women who serve as LHAs and more broadly in African-American communities.

Methods

Recruitment

We contacted eight NWP sites in the northeast, south, and mid-west, selected from 20 national sites that had attended the most recent NWP Annual Meeting. We used purposeful sampling in an attempt to represent a full range of sites and LHA experiences (e.g., sites and LHAs with varying levels of activity). Following the meeting, the NWP local program director and the study principal investigator informed LHAs about the study through a letter, phone, and/or presentations at scheduled local meetings and trainings. LHAs interested in participating provided written permission to be contacted. All interested LHAs were contacted by telephone to consent them and schedule the telephone-based interview. Institutional Review Board approval was awarded through Columbia’s Mailman School of Public Health. A total of 84 eligible LHAs were identified and provided their contact information; of those, 76 women participated in the study (response rate = 91%) at baseline and 68 of these women participated at follow-up.

Eligibility and data collection

To participate in the study, individuals had to be (1) self-identified as African-American or black, (2) female, (3) a LHA from the NWP (currently or within the past 2 years), (4) over the age of 18, and (5) English-speaking. We chose a convergent parallel mixed-methods design for the overall design of the study [51], with data collection for qualitative and quantitative components occurring simultaneously. The quantitative data, reported elsewhere [36], tested a conceptual model focused on understanding which LHA-related characteristics and role-related factors predicted LHA retention and participation. The goal of the qualitative data, presented here, was to inform a more in-depth and comprehensive understanding of factors that influence long-term NWP program implementation and sustainability, and to increase the likelihood we had identified the full range of factors, including organizational and contextual factors that were not measured in the quantitative study.

Baseline in-depth interviews and surveys took place by telephone between 2010 and 2012 (see Table 1) and follow-up in-depth interviews and surveys took place by telephone 12–18 months later. Study participants received a $25 gift card for each interview, which lasted 60–90 min. Interviews were audio-taped and professionally transcribed. We chose to have two time points for data collection in an effort to increase the likelihood that we had identified a comprehensive range of factors and to identify any new challenges or facilitators that arose over time. A semi-structured interview guide was developed, with general areas for investigation informed in part by the existing literature and sustainability frameworks [7, 11]. The questions asked were consistent at baseline and follow-up (see sample questions in Table 1).

Table 1.

Examples of topics and questions covered related to implementation and sustainability

| Initial and ongoing motivation to be a LHA | What motivates you to be a LHA, initially and continually? What benefits do you receive through being a LHA? |

| Broader impact of NWP program | How has being a LHA impacted your social networks, family, and community? How has being a LHA impacted you personally? |

| Facilitators and barriers to serving as a LHA | What are challenges or barriers to your participation as a LHA? What factors affect your activity level and participation as a LHA? What supports you in your role as a LHA? |

| Factors that support the ongoing implementation and sustainability of NWP | What do you think makes the NWP successful? What makes the program effective and supports its continued implementation? What factors support the program’s long-term continuation? |

| Factors that impede the ongoing implementation and sustainability of NWP | What are challenges or barriers to continuing to implement NWP? What are challenges or barriers to sustaining the program? |

Data analysis

Documents were analyzed using an immersion and crystallization process and thematic content analysis [52]. Analyses followed a systematic process whereby all transcripts were independently read through by two independent coders as text for general familiarity (the PI and RA, both trained in qualitative research). Following the identification of general domains and codes, texts were subjected to systematic, line-by-line coding based on initial categories from our interview guide. An iterative approach was taken in which the coding scheme remained flexible and open to accommodate the expansion of codes. Disagreements on coding were resolved through consensus among the investigative team. Content analysis was conducted on the data once it had been coded, identifying recurring patterns, themes, and sub-themes that emerged, including illustrative quotes. Coding and analysis were facilitated by the use of Dedoose qualitative software. Findings were shared with program directors and LHAs to ensure accuracy of our interpretations (e.g., member check). Of note, the quantitative data from this study was analyzed independently from the qualitative data; the mixing of results occurred during the interpretation phase to understand points of divergence and convergence, as presented in the “Discussion” section.

Results

Characteristics of the sample

Sociodemographic characteristics are displayed in Table 2. Seventy-six (76) female LHAs participated in this study; half (50%) (n = 38) were breast or cervical cancer survivors. Over 40% of women had associate’s or university degrees and about half were unemployed (predominately related to retirement). LHAs were involved in the program for a mean of 65.8 months (approximately 5 1/2 years), ranging from 0 months (newly trained LHAs) to 16 years. Ninety-two percent (92%) of LHAs were in voluntary NWP positions (i.e., were reported not being paid a salary for being a LHA by NWP or the organization where NWP is based). Geographic locations of the sites are also provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic characteristics of African-American lay health advisors from the National Witness Project (NWP) (n = 76)

| All LHAs (N = 76) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Study site | Harlem, NY | 14 (18%) |

| Syracuse, NY | 10 (13%) | |

| Little Rock, AR | 17 (22%) | |

| Long Island, NY | 5 (7%) | |

| Tampa, FL | 6 (8%) | |

| Chicago, IL | 4 (5%) | |

| Buffalo, NY | 17 (22%) | |

| Wichita, KS | 3 (4%) | |

| Type of institution | Academic | 54 (71%) |

| Non-academic | 22 (29%) | |

| Length of activity in role (months) | Mean (SD) [range] | 65.8 (53.0) [0–192] |

| Employed | Employed by NWP | 6 (8%) |

| Employed FT outside of NWP | 24 (32%) | |

| Employed PT outside of NWP | 7 (9%) | |

| Not employed | 29 (51%) | |

| Position in NWP | Paid | 6 (8%) |

| Voluntary | 70 (92%) | |

| Age | Mean (SD) [range] |

54.9 (13.5) [21–78] |

| Education | ≤Some college | 30 (39%) |

| Associate’s or university graduate | 33 (43%) | |

| Graduate or professional degree | 13 (17%) | |

| Annual household income | <$10,000–$24,999 | 16 (21%) |

| $25,000–$49,999 | 22 (29%) | |

| >$50,000 | 32 (42%) | |

| Refused | 6 (8%) | |

| Marital status | Married | 32 (42%) |

| Never married | 23 (30%) | |

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 20 (26%) | |

| Cancer survivorship status | Cancer survivor (yes) | 38 (50%) |

| Healthcare summary | Have primary care provider (yes) | 69 (91%) |

| Primary insurance | Medicaid or Medicare | 31 (41%) |

| Employer-provided insurance | 33 (43%) | |

| None/other | 12 (16%) |

Qualitative themes

Key themes and sub-themes are reported below, with illustrative quotes associated with each theme provided in Table 3. Some passages of text were coded under multiple categories, and some themes are inter-related (e.g., quotes related to organizational infrastructure may also relate to issues of leadership and funding); we present quotes under the theme that was most salient. Of note, we compared themes at baseline with those at follow-up to determine if there were substantial differences in themes; we found they were consistent across both time points, so we have presented them together. We also compared whether the themes differed between women who were active or non-active at follow-up and found that themes were similar across participants, though LHAs who were not active at follow-up tended to focus more on challenges associated with the program.

Table 3.

Illustrative quotes that highlight key themes related to NWP implementation, sustainability, and impact

| Funding | “The big thing that I don’t like is that we don’t have the funds we need…many of our projects don’t have resources they need in order to do the programs we need to do. …if we had better funding we could train more women and we would have more women to get out and do this work. And women get burned out… if you are the only two or three ladies that are doing it then you soon get burned out but if you could get more women involved and that requires funding then it would help our programs to grow.” “… I don’t like that I get discouraged finding money to sustain our programs or lose programs more often than we should…it’s just not supported around the country” |

| Partnerships | “… the Witness Project as an organization would be able to help a person to get transitioned into or gain access because they partner a lot of times with a lot of the resource fairs… there will be another component of the cancer center that will come out with their bus, with their equipment the mammogram do free mammography and different things like that. So there we’re fortunate in that we have a partnership with a cancer research hospital where there may be some of those resources that are available that we would have influence with.” “We are aspiring to be more and more involved and collaborating with other health agencies and many times that information is not available to us but we are beginning to know what agencies are available and how we can refer people to the different agencies for whatever their needs may be.” |

| Leadership/program champion | “…folks don’t always understand that you’ve got to have a leader you have got to have someone giving direction. You have got to have nationally giving direction you have to have administratively someone giving direction to get the volunteers out there doing what they need to do and doing it effectively.” “First of all I would say it’s XX and XX…they are committed, they have a good vision, they do whatever needs to be done and they get it done. They have a wonderful network of people that they’ve connected with to provide a greater, a broader level of support than just two people can provide.” |

| LHA staffing and commitment | “What makes it successful, because you have dedicated people…they are concerned about people and the goal is to let people know that there is life after cancer. You don’t have to crawl up in your bed and die, life is after, there is life after cancer and there is a good a quality to life after cancer.” “I love the revelation that comes from doing this kind of work, I like to see the light come on for people.” “I had lost two family members to cancer and I know how devastating the disease is…I guess this is kind of my outlet and my way to give back to the community…” “I have become a better person from it and I plan to be a Lay Health Advisor for a very long time.” “It’s one thing, I think on paper, to just provide outreach screening and insurance support for people. The emotional side of what happens to someone who has to deal with having cancer, recovering from it, counting every anniversary that you have that you are cancer free watching other people die from it is just huge, and we should not be expecting women to deal with this in full isolation. So having a group, a support group, a place where you can go and talk and share, and even just sometimes to vent about how hard it is or how happy you are to be a survivor is I think critically important in terms of emotionally surviving.” |

| Perceived need and fit of the program in African-American community | “Well first of all I felt that our community, the African American community, is not informed enough about what is going on in the community and I feel that also that we are more trusting of our own people when they bring information to us so that is one of the reasons why I got involved, I felt that you know we weren’t…the fact that the African American community was just not being informed or not listening as they should to information that could save their lives.” “I like the sense of sisterhood, I like that especially that is women of color because like I said in our community often we do not take [care] of ourselves or we take care of ourselves last and that we are just helping one another to become more and better informed about our health.” |

| Organizational infrastructure | “We don’t have an office space that we can have our own materials laid out when we do programs, make it easy access to, to load up everything and have regular meetings. The hospital provides us with a place to meet, that having a space of our own, but those are the logistical things.” “We just happened to have a funder who came and said we are going to fund you but we want you to get your infrastructure and the important thing this year is your infrastructure. So we are on two paths…I have volunteers who are on the program path and I, with our funder, are on the administrative path and the infrastructure part…we have to create our structure and so we are just in the midst of doing it.” |

| Implementation processes | “I think the self sustainability of the volunteers training each other and training other people who train other people just the fact that it is a volunteer power house, it is definitely something that people want to do, it is not necessarily imposed and I feel like that is a very critical way for people to stand by because they want to and they are in it because of you know just their own free will and I feel like that’s just a really good aspect of the self sustainability of the program.” |

| Broader impact | “I remember years ago I was ashamed to and afraid to talk to people and the audience of people I will be scared to death to speak and I think by being a part of Witness it keeps giving me strength to be able to go and stand before an audience of people and talk. Now I am not scared, I am not ashamed, I am not any of those things I used to be years ago, and each time I do it, it just keeps on giving me more strength to be able to stand out there and say things.” “I like the fact that I help save lives I like the fact that I try as hard as I can to accomplish a mission given to me and I like the fact that what I have and what I am can translate into helping someone else, giving someone else a float. It’s like reaching out to someone who has fallen overboard that’s how I feel about it and all you have to do is make contact with a finger and pull them back to shore.” “So it has helped me gain not only this boldness, boldness to be able to share, to educate so I think it really has helped me in the communication skills and just being able to get up and speak in front of a large audience, large or small.” “We genuinely care about each other it’s not just a job it is something that is meaningful it’s not just something that we do for the sake of doing something. But it’s something meaningful.” |

Across themes, we found that factors related to context (funding, partnerships, leadership, organizational infrastructure) and related to LHA staffing (e.g., personal and social motivations and commitment to role) were the most salient themes (e.g., most commonly mentioned and identified by participants as most influential), while factors related to implementation processes (e.g., training) and intervention characteristics (e.g., perceived need for program) were coherent themes, but less frequently discussed.

Factors influencing continued NWP implementation and sustainability

Funding.

Limited funding and resources were the most frequently cited factors and were a point of frustration that put tremendous strain on their ability to continue to implement and sustain NWP. As stated by one LHA: “Most of the time resources and money are in short supply and we really have to do more with less. You are constantly in a state of trying to reach a maximum number of people with the limited amount of resources and money.” There was a common assertion that funding issues at the policy level affected their ability to implement and sustain the program (e.g., loss of the state-level breast and cervical cancer program that provided screening, diagnosis, and treatment to underinsured women; reductions in funding for breast/cervical cancer education nationally). Budget and grant/funding cuts were mentioned often in relation to the economic recession that was ongoing at the time of data collection. A few LHAs expressed confusion over why less funding would be available when women of color are more likely to die from the disease: “…I just feel that we need more funding…I just don’t understand it…I’m taking it because we are women of color and for whatever reason it’s not getting the attention it should get.” Funding issues locally at the organizational level were also discussed as a common strain (e.g., budget cuts at the health department that impact their program), as were challenges related to the instability and inconsistency of financial resources available (e.g., funding they had to apply for annually).

The perceived implications of funding cuts were broad-reaching and commonly discussed and included having no or few programs per month or significant reductions in the number of LHA programs offered, not being able to pay LHAs a stipend or having LHAs overextended and experiencing burnout, reaching fewer women and not being able to help connect women to free mammogram services, inability to conduct program evaluation, and challenges related to supporting the infrastructure and administration of the program.

Most LHAs cited foundation funding and funding from the state (typically re-applied for annually) as key resources that sustained their program. Some LHAs also discussed grant-writing at their sites (often through partnerships with academic centers or, more rarely, with an internal grant-writer) and the need to do more fundraising and marketing for the program. A few sites relied on personal resources to help sustain the program during difficult times.

Partnerships.

Partnerships with community-based organizations and academic organizations were perceived by most LHAs as critical support systems that facilitated their ability to implement and sustain NWP programs. Partnerships with academic centers, hospitals/cancer centers, health departments, foundations (e.g., Komen Foundation), as well as churches and senior/community centers were commonly mentioned. As one example: “We’re fortunate in that we have a partnership with a cancer research hospital where there may be some of those resources that are available that we would have influence with.” The purpose of these partnerships varied and typically existed at the state and/or local level; in some cases, they helped facilitate access to services (e.g., low cost or free mammography screening, referrals to provider networks, diagnostic follow-up, support groups for survivors) or provided access to critical materials and resources (e.g., cancer-related information, space to hold programs or to administratively house the site). Some partnerships were with one or two key organizations. In a few cases, coalitions or networks of health-related resources had been built in their community.

Leadership and program champions.

NWP leadership at the local and national level was identified by most LHAs as being critical to NWP’s success and continued implementation. According to one LHA, “The leadership are so supportive…I can’t help but turn around and support them.” These leaders or program champions at the local level (commonly the NWP program director) were perceived as being integral to making contacts and connections in the community to implement the program. According to one LHA: “…that’s what helps us to be successful- that person who is networking and doing the leg work to get these events scheduled and these opportunities for us…it’s a vital part of our success.” Other important NWP leadership activities included providing a vision for the site and providing emotional support to staff, volunteers, and program attendees (“…You can’t run a tight ship if you don’t have a good captain and she is an excellent captain, she’s very hard working, she stays on the go but she takes care of her people.”). A few LHAs reported interest in having more national support and leadership in place to support sites at the local level: “I think they need to do a little more at the national level in getting information and direction and visibility to the local levels and help their partnerships with all their organizations out in the field. We are their arms and their legs but they are the umbrella that has to make it all work.”

Organizational infrastructure.

Building and maintaining an organizational infrastructure was one of the biggest challenges often mentioned with respect to sustaining the NWP in the community and was closely linked with financial issues. Many LHAs highlighted “how important infrastructure is to keep the organization running afloat,” both at the national and local level. One issue expressed was the need to create and maintain leadership or administrative positions that are not on a volunteer basis, in order to provide stability, program visibility, and serve as a form of institutionalization. At the local level, the biggest infrastructure challenge for some sites was not having an office space of their own and the logistical issues this introduced. A few LHAs also discussed ongoing work at the national level to establish NWP’s own community board and the development of an administrative national foundation for NWP (with non-profit status) “to promote ‘operational longevity.” According to one LHA: “We need bigger activity that is nationally recognized, we need that national platform so that African-American women and all women need to be educated….”

Implementation processes.

Initial and ongoing training was identified by most participants as a critical strategy that promoted program implementation and sustainability, in that it facilitated knowledge, role-playing practice and built self-efficacy. Limited resources often impeded NWP’s ability to provide ongoing and widespread training; for example, funding issues had prevented them from having an annual conference that provided an opportunity to convene and provide updated education to all LHAs across the country. The “train the trainer model” that NWP uses was perceived by some participants as “a really good aspect of the self-sustainability of the program” that allowed NWP to develop a “volunteer power house.” While several women acknowledged evaluation as an important process and potential strategy to support sustainability, they also acknowledged the challenges of continually doing so given the funding environment. A few LHAs suggested that NWP would benefit from having a marketing/communications or planning team that would provide information and publicity about the program and its successes, using the evaluation data.

LHA staffing and commitment.

There was strong consensus that the passion and commitment of the staff and LHAs was vital to the ongoing implementation of the NWP, particularly in sites that had predominately volunteer LHAs. According to one LHA: “I think the passion of the volunteers that we have, I think the passion of the director who first started the program and I think the passion of the program coordinator who actually runs it and puts everything together, I think that makes it successful.” Many mentioned the desire to provide stipends to LHAs to provide financial support for this work, but given the economic context and funding constraints, this was not always possible. The majority of LHAs reported being initially motivated to become a LHA by their desire to “give back” and contribute to their community, as well as personal experiences with cancer (their own experience or experiences of family/friends) (“my real motivation is my personal connection with cancer.”)

Most LHAs reported personal and social factors that continued to motivate them remain in their roles, including the development of new social networks and emotional support from other LHAs and leaders, encouragement and recognition from their family and community, and the sense of empowerment they experienced through the program (e.g., felt like they were making a difference, “saving lives”). In terms of the continued implementation and success of the program, a number of LHAs perceived the sharing of the stories and personal experiences of the cancer survivors to be particularly critical, especially in being able to make a powerful emotional connection with the women in the community. Some LHAs who were cancer survivors discussed how “healing” it was for them to share their stories. According to one LHA: “So that’s what continues to motivate me because I find that when I get back I’m healed in the process of helping someone else heal.”

Challenges pertinent to LHA staffing and participation related to LHA burnout or low participation, particularly in sites where there were few LHAs or they were taking on multiple roles and responsibilities (“…There’s not enough women specifically for our site… a lot of people can get burned out,”) and a few women’s participation was limited by other competing demands (e.g., school, work) or by their inability to receive salary/benefits through the position.

Perceived need and fit of the program in African-American community.

Some LHAs reported that part of the successful continuation of NWP is that it has filled a critical need in the African-American community to address and discuss cancer and cancer screening, particularly since historically there has been much shame and stigma associated with cancer. It was recognized that NWP was developed for and by African-American women in the community: “I think the dedication of the ladies…we as African American women in the past have not had a lot of programs and activities that are designed for us…the emphasis and the start of this program was designed for African American women and I think that makes a big difference.” The program’s focus on addressing social and health inequities among African-American women was highly valued by LHAs. Having the program rooted in the community and faith-based settings was perceived by most as an asset for being able to implement the program in the community, reduce medical mistrust, and reach underserved women: “…I think the fact that we are who we are and we are on the platform that we are being a faith based program that you know it knocks out some doors, it removes some barriers that may not be easily moved if we didn’t have that platform.”

A few participants also mentioned expanding or adapting the program beyond screening by being responsive to the needs of the women in their community (e.g., more emphasis on self-care and overall wellness, teaching how to advocate for oneself in the health system, obtaining insurance and access to care, creating survivor support groups). There was also recognition from a few LHAs that screening recommendations have changed from when the program first started, and there is a need to stay current with changing scientific evidence: “…when I first started doing it the focus was to encourage women to do self breast exam and then go in and get an exam by a physician to be followed up with a mammogram and now there is lesser of an emphasis on the self exam and more to go in and just, you know things keep changing....”).

The broader impact of NWP on LHAs and their communities

Building capacity in African-American communities.

Participants referred to the effectiveness and impact of the program in educating underserved women and facilitating breast and cervical cancer screening. Moreover, LHAs commonly discussed how the program had a much larger impact in their families, churches, and community networks beyond the impact on women who attend the educational programs (“there is a ripple that goes out from you that touches other people’s lives positively”). According to one LHA: “…I am going to always be a Witness member whether actually a part of the group or not I am always going to share the fact that women should get their screening early and protect their selves and be sensitive to their own bodies get to know their bodies, so I am going to always teach that in church or with the Witness Project or wherever.” Some LHAs also reported how the program built LHA capacity to address other needs within the community, beyond their role as a LHA: for example, participation in the program as a LHA encouraged one woman to start her own non-profit organization, another grew her counseling business to focus on spousal and patient cancer diagnosis support, and other LHAs were encouraged to volunteer for other organizations in their community.

Personal impact on LHAs-building capacity of LHAs as leaders.

Participation in NWP also had tremendous impact on the LHAs who served in these roles as in terms of empowering women, developing new skills, and building leaders in their community. Many LHAs noted that it provided a platform for them in their community; nurtured their confidence and assertiveness; built their communication/public speaking, listening, and computer skills; enhanced their knowledge and capacity related to cancer and cancer prevention; and encouraged pursuit of educational or professional advancements. For many women, it helped them learn to self-advocate and take better care of their own health. According to one woman: “I think it’s a reinforcement, the more engaged that you are in organizations like Witness then the more you feel necessity to really walk the walk as well as talk the talk.” Another LHA stated: “I’d say it has empowered me definitely as far as I can say the knowledge that I’ve gained and also just the sense of being part of an active group working on an important health issue both in a kind of a professional way but also socially…I feel very much empowered by that having that experience.”

Social networks and support were an additional important benefit that almost all LHAs reported experiencing. Cancer survivors identified this as being particularly important for their own health and recovery, to prevent the social isolation and depression that can accompany cancer and to promote their own health and wellness. According to one LHA survivor: “Well, the benefit has been that I feel more encouraged myself that I can face whatever obstacles come my way concerning the breast cancer, I can face it now better than I could when I first found out and I feel strongly the fact that I can speak to others about it….” The support provided extended beyond issues related to cancer survivorship. One LHA stated: “I mean it literally gets your heart popping and keeps you up; I mean it is a great sisterhood it is a great support system. It’s a support system for not just breast and cervical cancer because once someone becomes your sister then all kinds of aspects of support.”

Discussion

We conducted in-depth qualitative interviews at two time points among 76 LHAs from eight NWP sites to advance understanding of factors that affect the long-term implementation and sustainability of this community-engaged LHA program. Commonly cited challenges and impediments to sustainability included inconsistent and unstable funding and budget cuts at the national and local levels, few resources to support organizational capacity and infrastructure (e.g., limited paid administrative positions for local leadership, challenges related to finding space to serve as home-base for program), limited implementation processes in place to support evaluation or marketing to raise national visibility of the program, as well as challenges related to active staffing of LHAs (e.g., burnout).

Factors and facilitators identified as supporting continued program implementation and sustainability included key partnerships with academic/medical centers and community organizations to facilitate access to resources or capacity (e.g., access to space, connections to funding sources); committed leadership and program champions who supported the staff, provided a vision, and organized the program; initial and ongoing training; and passionate LHAs who gained tremendous personal, social, and professional benefits through their participation which motivated their ongoing participation (often as volunteers). Additional aspects of the program that were viewed as critical to its success included that it was developed for and by African-American women and sought to address health inequities in communities, as well as the central role of cancer survivors in the program.

Our findings are consistent with and expand upon the limited research that has previously been conducted on the sustainability of programs in community settings that suggest that in addition to funding, organizational and contextual factors are critical to understand [7, 13]. We are the first to document these factors in community settings for African-American-focused LHA programs. Prior research on implementation and sustainability challenges among community health workers and promotores suggested that staffing, organizational costs, funding, evaluation challenges, and lack of political and financial support are important factors for consideration [34, 35].

Our findings also expand upon and complement our prior work from this larger mixed-methods study. We prospectively and quantitatively tested a conceptual framework of individual, social, and LHA role-related factors and one organizational factor (organizational partnerships) that predicted LHA participation and retention as an indicator of NWP sustainability. We found that the organizational factor was the most impactful: LHAs who were located at NWP sites with strong partnerships with academic institutions were 80% more likely to be retained and highly active about 18 months later [36]. Sites with academic partnerships were more likely to have strong organizational infrastructure and processes in place (e.g., provision of stipends to their LHAs, regular trainings, and dedicated physical space). This is also consistent with an earlier replication study conducted by our group that found that having organizational partnerships and both community and academic champions were crucial for successful replication of NWP [11]. The quantitative data from the larger mixed-methods study presented here also suggested that LHA role-related factors, including role self-efficacy, clarity, and commitment, may also have a positive influence on LHA participation and retention [36]. Based on the triangulation of qualitative and quantitative data across our study, we found convergence in identifying a range of factors across multiple levels that likely influence continued sustainability of community-based LHA programs. However, across both studies, the data suggests that factors at the organizational and contextual levels and related to the motivations and characteristics of LHAs may be particularly influential.

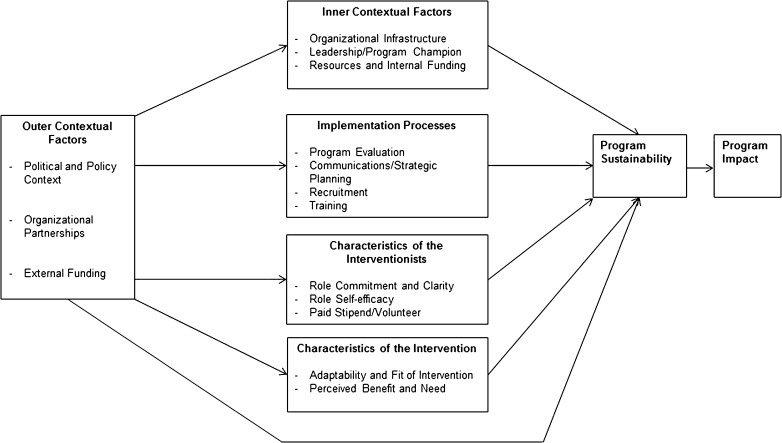

The research reported here has important implications for informing conceptual models in implementation science, including ones focused specifically on sustainability in community settings. Some researchers have argued that sustainability must be studied distinctly from implementation and should be specific to intervention context [6, 11, 53]. Conceptual frameworks specific to sustainability have been few and rarely tested, and there is no “gold-standard” in the field. We have developed the LHA Sustainability Framework (see Fig. 1), informed by seminal conceptual frameworks that have been previously developed to understand program sustainability in general and that share similar and overlapping constructs [6, 54, 55]. As recommended by sustainability experts [7, 56], we have adapted and contextualized these frameworks for community-based LHA programs based on the triangulation of findings from our qualitative research reported here and our prior quantitative research [36]. The LHA Sustainability Framework highlights several overarching characteristics, including (1) outer contextual characteristics (policy environment and funding, organizational partnerships), (2) inner contextual characteristics (organizational infrastructure and support, leadership and program champions, funding), (3) implementation processes (e.g., recruitment, training, strategic planning and communication, evaluation), (4) characteristics of interventionists (role commitment and motivation, self-efficacy, payment), and (5) intervention characteristics (perceived benefit/need for program, program fit and adaptability). Research is needed to empirically test this conceptual framework through quantitative prospective studies to understand which factors are most critical in predicting program sustainability of community-based LHA programs.

Fig 1.

The lay health advisor sustainability framework

Furthermore, while most prior research on LHAs has focused on the effectiveness of LHA programs for program attendees [27, 32], our research has helped to document some of the long-term impacts of implementing and sustaining LHA programs and the capacity that is built among LHAs and in African-American communities. Examples included a “ripple-effect” of the program to LHAs’ friends, families, and social networks, beyond the scope of the NWP educational sessions they conduct, suggesting the program has much bigger reach and impact in its contribution to cancer prevention and control. Participation as LHAs also affected many aspects of the women’s lives, particularly among LHAs who are cancer survivors. Examples included increased and strengthened social networks and support, professional development (e.g., public speaking, communication skills), expertise in navigating health systems, and personal development and health (e.g., increased confidence and assertiveness in their own life, enhanced self-worth in making a difference in their community). These findings complement our prior quantitative research on the multi-level capacity that is built through LHA programs [50].

Limitations should be recognized. Our findings are primarily generalizable to LHA programs in community-based settings among racial/ethnic minority populations, including programs that involve cancer survivors as LHAs. Though we had excellent participation, there may be differences between those that participated and those who did not given that the sample was not randomly selected. While we recruited from eight NWP sites, there are currently about 20-23 sites that have been active in recent years, and our sites were predominately in the south, northeast, and mid-west; therefore, we may not have represented all NWP site experiences. There are also limitations to telephone interviews, given the inability of interviewer and research participants to observe visual cues and body language. Strengths of the study should also be recognized. We conducted data collection from eight urban and rural sites in the USA and had a high response and retention rate among LHAs. We conducted research among African-American LHAs in the US context, a population and setting that has been highly underrepresented in this literature. Additionally, we collected data longitudinally at two time points among LHAs to fully support understanding of factors that impact sustainability. LHAs from NWP are well-suited to provide their perspectives on these issues given that the program is community-led with sustained and high levels of participation among many LHAs that facilitate knowledge of programmatic issues (the mean years of LHA participation was 5.5 years, with some LHAs having up to 16 years of experience). Furthermore, some LHAs were currently serving or historically served as paid staff in the program (six women were both LHAs and paid staff in our sample), and some NWP sites hold regular steering committee meetings; both of these factors may enhance institutional knowledge among LHAs.

Our results also contribute to limited research on the long-term implementation and sustainability of evidence-based programs, as opposed to the initial implementation of programs, which is more commonly discussed in the literature. This is because the program we are studying, NWP, was developed nearly 25 years ago, and the sites we included in our study were replicated predominately in the 1990s or early to mid-2000s. However, we recognize that some factors we have identified do overlap with factors associated with initial implementation (and associated frameworks) in the literature [57, 58]. Future research should help identify empirically where there are areas of overlap and divergence in factors related to initial implementation and long-term implementation and sustainability.

Very little research has tested strategies and interventions to promote the sustainability of LHA programs in community settings. The limited research that has been conducted suggests that a multi-level, localized or context-specific approach may be important and that planning and partnerships in the community will be critical [59]. Our research further informs potential strategies to address sustainability of LHA programs in the community and suggests that strategies that focus on the inner and outer context (e.g., obtaining funding, building organizational infrastructure, developing partnerships, building leadership, identifying program champions) may be particularly promising. Our finding that some sites and LHAs have been expanding or adapting the NWP program to be responsive to women’s needs and changing scientific evidence in the area of cancer screening suggests that understanding the tension and balance between fidelity and adaptation in the context of long-term program sustainability is a critical area for future investigation [60]. Developing and testing evidence-based strategies and policies that promote sustainability of LHA programs should be a priority area for future research.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the NWP National Steering Committee, project directors, coordinators, LHAs, and role models from the National Witness Project who contributed their time to this study. In particular, we would like to thank and acknowledge Detric “Dee” Johnson and Mattye Willis for all of their efforts and support. This research was funded by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (5R03CA150543-03, “Serving as a Lay Health Advisor: The Impact on Self and Community”). Thank you to Danielle Crookes for her editorial assistance with this article.

Compliance with ethical standards

Funding

This research was funded by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (5R03CA150543-03, “Serving as a Lay Health Advisor: The Impact on Self and Community”). The Lerner Center for Public Health Promotion at Columbia School of Public Health provided support for Thana-Ashley Charles to assist on the project as a Lerner Center Fellow.

Statement of human rights/Helsinki statement

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1975 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

IRB approval

Institutional Review Board approval was awarded through Columbia University.

Animals

This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Implications

Practice:

Multiple factors are likely to facilitate the sustainability of community-engaged LHA programs including key partnerships with academic/medical centers and community organizations to build capacity and facilitate access to resources and funding, committed leadership and program champions, initial and ongoing training, and passionate LHAs who gain personal and professional benefits through their participation.

Policy:

National, state-level, and local policies and funding sources are critical to the long-term sustainability of LHA programs in community settings; furthermore, policymakers should consider the broader impact of LHA programs to build leadership and capacity in underserved communities.

Research:

Future studies should empirically test which theoretically informed factors predict long-term sustainability of LHA programs in community settings and explicitly develop and test strategies to promote and plan for program sustainability.

This research has not been previously published and the present manuscript is not simultaneously being submitted elsewhere. There has been no previous reporting of the data. The authors have full control of the primary data and agree to allow the journal to review the data if requested.

Contributor Information

Rachel C. Shelton, Phone: 212-342-3919, Email: rs3108@cumc.columbia.edu.

Thana-Ashley Charles, Email: tnc2115@cumc.columbia.edu.

Sheba King Dunston, Email: drshebaking@gmail.com.

Lina Jandorf, Email: Lina.Jandorf@mssm.edu.

Deborah O. Erwin, Email: Deborah.Erwin@RoswellPark.org.

References

- 1.Neta G, Sanchez MA, Chambers DA, et al. Implementation science in cancer prevention and control: a decade of grant funding by the National Cancer Institute and future directions. Implementation Science. 2015;10(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s13012-014-0200-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glasgow RE, Vinson C, Chambers D, Khoury MJ, Kaplan RM, Hunter C. National Institutes of Health approaches to dissemination and implementation science: current and future directions. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(7):1274–1281. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.America IoMCoQoHCi 2001. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. National Academy Press. [PubMed]

- 4.Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK. (2012). Dissemination and implementation research in health: translating science to practice. Oxford University Press.

- 5.Proctor E, Luke D, Calhoun A, et al. Sustainability of evidence-based healthcare: research agenda, methodological advances, and infrastructure support. Implementation Science. 2015;10:88. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0274-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scheirer MA, Dearing JW. An agenda for research on the sustainability of public health programs. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(11):2059. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scheirer MA. Is sustainability possible? A review and commentary on empirical studies of program sustainability. American Journal of Evaluation. 2005;26(3):320–347. doi: 10.1177/1098214005278752. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whelan J, Love P, Pettman T, et al. Cochrane update: predicting sustainability of intervention effects in public health evidence: identifying key elements to provide guidance. Journal of Public Health. 2014;36(2):347–351. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdu027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bovbjerg RR, Eyster L, Ormond BA, Anderson T, Richardson E. The evolution, expansion, and effectiveness of community health workers. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodwin K, Tobler L. (2008). Community Health Workers: Expanding the Scope of the Health Care Delivery System. National Conference of State Legislatures. Available from: http://www.ncsl.org/print/health/chwbrief.pdf. 1:2.

- 11.Shediac-Rizkallah MC, Bone LR. Planning for the sustainability of community-based health programs: conceptual frameworks and future directions for research, practice and policy. Health education research. 1998;13(1):87–108. doi: 10.1093/her/13.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tibbits MK, Bumbarger BK, Kyler SJ, Perkins DF. Sustaining evidence-based interventions under real-world conditions: results from a large-scale diffusion project. Prevention Science. 2010;11(3):252–262. doi: 10.1007/s11121-010-0170-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fagen MC, Flay BR. (2006). Sustaining a school-based prevention program: Results from the Aban Aya sustainability project. Health Education & Behavior. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Cooper BR, Bumbarger BK, Moore JE. Sustaining evidence-based prevention programs: correlates in a large-scale dissemination initiative. Prevention Science. 2013;16(1):145–157. doi: 10.1007/s11121-013-0427-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palinkas LA, Chavarin CV, Rafful CM, et al. Sustainability of evidence-based practices for HIV prevention among female sex workers in Mexico. PloS One. 2015;10(10):e0141508. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paine-Andrews A, Fisher JL, Campuzano MK, Fawcett SB, Berkley-Patton J. Promoting sustainability of community health initiatives: an empirical case study. Health Promotion Practice. 2000;1(3):248–258. doi: 10.1177/152483990000100311. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson K, Hays C, Center H, Daley C. Building capacity and sustainable prevention innovations: a sustainability planning model. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2004;27(2):135–149. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2004.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tabak RG, Duggan K, Smith C, Aisaka K, Moreland-Russell S, Brownson RC. (2015). Assessing capacity for sustainability of effective programs and policies in local health departments. Journal of public health management and practice: JPHMP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Aarons GA, Green AE, Willging CE, et al. Mixed-method study of a conceptual model of evidence-based intervention sustainment across multiple public-sector service settings. Implementation Science. 2014;9(1):183. doi: 10.1186/s13012-014-0183-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hunter SB, Han B, Slaughter ME, Godley SH, Garner BR. Associations between implementation characteristics and evidence-based practice sustainment: a study of the adolescent community reinforcement approach. Implementation Science. 2015;10(1):173. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0364-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peterson AE, Bond GR, Drake RE, McHugo GJ, Jones AM, Williams JR. Predicting the long-term sustainability of evidence-based practices in mental health care: an 8-year longitudinal analysis. The journal of behavioral health services & research. 2014;41(3):337–346. doi: 10.1007/s11414-013-9347-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fisher, E. B., Coufal, M. M., Parada, H., et al. Peer support in health care and prevention. Cultural, organizational, and dissemination issues, 352014, 363–383. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Earp JAL, Viadro CI, Vincus AA, et al. Lay health advisors: a strategy for getting the word out about breast cancer. Health Education & Behavior. 1997;24(4):432–451. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eng E, Parker E. Natural helper models to enhance a community’s health and competence. In: Diclemente RJ, Crosby RA, Kegler MC, editors. Emerging theories in health promotion practice and research: strategies for improving public health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002. pp. 126–156. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eng E, Parker E, Harlan C. Lay health advisor intervention strategies: a continuum from natural helping. Health Education & Behavior. 1997;24(4):413–417. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Viswanathan M, Kraschnewski J, Nishikawa B, et al. (2009). Outcomes of community health worker interventions. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 181.

- 27.Earp JA, Eng E, O'Malley MS, et al. Increasing use of mammography among older, rural African American women: results from a community trial. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(4):646–654. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.92.4.646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Russell KM, Champion VL, Monahan PO, et al. Randomized trial of a lay health advisor and computer intervention to increase mammography screening in African American women. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2010;19(1):201–210. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paskett E, Tatum C, Rushing J, et al. Randomized trial of an intervention to improve mammography utilization among a triracial rural population of women. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2006;98(17):1226–1237. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Margolis KL, Lurie N, McGovern PG, Tyrrell M, Slater JS. Increasing breast and cervical cancer screening in low-income women. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1998;13(8):515–521. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00161.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Legler J, Meissner HI, Coyne C, Breen N, Chollette V, Rimer BK. The effectiveness of interventions to promote mammography among women with historically lower rates of screening. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2002;11(1):59–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wells KJ, Luque JS, Miladinovic B, et al. (2011). Do community health worker interventions improve rates of screening mammography in the United States? A systematic review. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. cebp. 0276.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Kiger H. Outreach to multiethnic, multicultural, and multilingual women for breast cancer and cervical cancer education and screening: a model using professional and volunteer staffing. Family & community health. 2003;26(4):307–318. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200310000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Twombly EC, Holtz KD, Stringer K. Using promotores programs to improve Latino health outcomes: implementation challenges for community-based nonprofit organizations. Journal of social service research. 2012;38(3):305–312. doi: 10.1080/01488376.2011.633804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koskan A, Friedman DB, Messias DKH, Brandt HM, Walsemann K. Sustainability of promotora initiatives: program planners’ perspectives. Journal of public health management and practice. 2013;19(5):E1–E9. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e318280012a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shelton R, Dunston SK, Leoce N, et al. Predictors of activity level and retention among African American lay health advisors from the National Witness Project: implications for the implementation and sustainability of community-based programs from a longitudinal study. Implementation Science. 2016;11(41):1. doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0403-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kkmoe M. Kalofonos I. Becoming and remaining community health workers: perspectives from Ethiopia and Mozambique. Social Science & Medicine. 2013;87:52–59. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alam K, Tasneem S, Oliveras E. Retention of female volunteer community health workers in Dhaka urban slums: a case-control study. Health policy and planning. 2012;27:477–486. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czr059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Erwin DO, Spatz TS, Turturro CL. Development of an African-American role model intervention to increase breast self-examination and mammography. Journal of Cancer Education. 1992;7(4):311–319. doi: 10.1080/08858199209528188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thompson HS, Valdimarsdottir HB, Winkel G, Jandorf L, Redd W. The group-based medical mistrust scale: psychometric properties and association with breast cancer screening. Preventive Medicine. 2004;38(2):209–218. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute. The Witness Project: Products. Research-tested Intervention Programs (RTIPs) 2012; http://rtips.cancer.gov/rtips/productDownloads.do?programId=270521. Accessed February 13, 2015.

- 42.Erwin DO. The Witness Project: narratives that shape the cancer experience for African American women. In: McMullin J, Weiner D, editors. In confronting cancer: Metaphors, advocacy, and anthropology. Sante Fe, CA: School for Advanced Research Seminar Series; 2009. pp. 125–146. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Erwin DO, Spatz TS, Stotts RC, Hollenberg JA. Increasing mammography practice by African American women. Cancer practice. 1999;7(2):78–85. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.1999.07204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kreuter MW, Green MC, Cappella JN, et al. Narrative communication in cancer prevention and control: a framework to guide research and application. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2007;33(3):221–235. doi: 10.1007/BF02879904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Erwin DO. Cancer education takes on a spiritual focus for the African American faith community. Journal of Cancer Education. 2002;17(1):46–49. doi: 10.1080/08858190209528792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hurd TC, Muti P, Erwin DO, Womack S. An evaluation of the integration of non-traditional learning tools into a community based breast and cervical cancer education program: the Witness Project of Buffalo. BMC Cancer. 2003;3(1):18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-3-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bailey EJ, Erwin DO, Belin P. Using cultural beliefs and patterns to improve mammography utilization among African-American women: the Witness Project. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2000;92(3):136. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arvey SR, Fernandez ME. Identifying the core elements of effective community health worker programs: a research agenda. American journal of public health. 2012;102(9):1633–1637. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Erwin DO, Ivory J, Stayton C, et al. Replication and dissemination of a cancer education model for African American women. Cancer Control. 2003;10(5; SUPP):13–21. doi: 10.1177/107327480301005s03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shelton RC, Dunston SK, Leoce N, Jandorf L, Thompson HS, Erwin DO. Advancing understanding of the characteristics and capacity of African American women who serve as lay health advisors in community-based settings. Health Education & Behavior. 2017;44(1):153–164. doi: 10.1177/1090198116646365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Creswell JW, Clark VLP. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 2007.

- 52.Borkan J. Immersion/crystallization. Doing qualitative research. 1999;2:179–194. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stirman SW, Kimberly J, Cook N, Calloway A, Castro F, Charns M. The sustainability of new programs and innovations: a review of the empirical literature and recommendations for future research. Implementation Science. 2012;7(17):1–19. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Luke, D. A. (2014). The program sustainability assessment tool: a new instrument for public health programs. Preventing Chronic Disease, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Aarons GA, Hurlburt M, Horwitz SM. Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2011;38(1):4–23. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Scheirer MA. Linking sustainability research to intervention types. American journal of public health. 2013;103(4):e73–e80. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science. 2009;4(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fixsen DL, Naoom SF, Blase KA, Friedman RM. Implementation research: a synthesis of the literature. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Strachan DL, Källander K, ten Asbroek AH, et al. Interventions to improve motivation and retention of community health workers delivering integrated community case management (iCCM): stakeholder perceptions and priorities. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene. 2012;87(5 Suppl):111–119. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.12-0030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chambers DA, Glasgow RE, Stange KC. The dynamic sustainability framework: addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implementation Science. 2013;8(1):117. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]