Abstract

Nutrition-related policy, system, and environmental (PSE) interventions such as farmers’ markets have been recommended as effective strategies for promoting healthy diet for chronic disease prevention. Tools are needed to assess community readiness and capacity factors influencing successful farmers’ market implementation among diverse practitioners in different community contexts. We describe a multiphase consensus modeling approach used to develop a diagnostic tool for assessing readiness and capacity to implement farmers’ market interventions among public health and community nutrition practitioners working with low-income populations in diverse contexts. Modeling methods included the following: phase 1, qualitative study with community stakeholders to explore facilitators and barriers influencing successful implementation of farmers’ market interventions in low-income communities; phase 2, development of indicators based on operationalization of qualitative findings; phase 3, assessment of relevance and importance of indicators and themes through consensus conference with expert panel; phase 4, refinement of indicators based on consensus conference; and phase 5, pilot test of the assessment tool. Findings illuminate a range of implementation factors influencing farmers’ market PSE interventions and offer guidance for tailoring intervention delivery based on levels of community, practitioner, and organizational readiness and capacity.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13142-017-0504-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Farmers’ market, Supplemental nutrition assistance program, Community readiness, Implementation science, Capacity, Nutrition

INTRODUCTION

Within the USA, chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, and obesity represent significant health burdens accounting for the majority of healthcare spending [1–3]. Increased consumption of fruits and vegetables is a key protective factor for the prevention of chronic diseases [4, 5]. There is growing evidence that access to fruits and vegetables tends to be less common in low-income and racial and ethnic minority communities where chronic disease rates are highest [6–9]. In response, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Education (SNAP-Ed) program, have made recommendations for implementation of nutrition-related policy, system, and environmental (PSE) interventions such as farmers’ markets to promote access to and consumption of fruits and vegetables as a broader strategy for reducing chronic disease trends and disparities [1, 10]. Farmers’ market PSE interventions include strategies focused on: (1) getting Electronic Benefit Transfer (EBT) machines at markets to accept Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits; (2) advertising about SNAP/EBT at markets; and (3) promoting incentive programs that increase the amount of benefit dollars that shoppers can use to purchase fruits and vegetables at markets. In this analysis, we sought to unpack the black box between these recommendations for implementation and wide-scale change by developing a diagnostic tool to assess community readiness and capacity influencing farmers’ market implementation among frontline practitioners working in public health and SNAP-Ed programs.

Just as individuals vary in their readiness to change, communities also vary. As Edwards and colleagues [11] noted, each community may be at different levels of readiness and capacity to initiate community-based interventions. Moreover, communities involve diverse groups with different background and perspectives. Due to this complex nature of community, there is a need for techniques, such as consensus modeling, that promote collaboration among key stakeholders to inform decision-making processes for implementing community-based interventions [12, 13]. The primary goals of consensus modeling methods are to determine the extent to which various stakeholders agree about causes and solutions to targeted issues through iterative discussion and reflection used to develop the best strategies for implementation [14–17].

Taken together, community-based interventions targeting chronic diseases are more likely to be successful if implementation is informed by careful assessment of community readiness and capacity that can be utilized to tailor intervention efforts [11–13]. Furthermore, the assessment of community readiness and capacity should be developed through close partnership and collaboration among key stakeholders to capture different viewpoints that will influence implementation of community-based interventions. Qualitative evidence suggests farmers’ market implementation is influenced by several organizational and community readiness factors including norms and beliefs, capacity, social capital, logistical factors, and sustainability issues [18]. However, these concepts have not been operationalized into diagnostic tools to inform farmers’ market implementation decision making across diverse contexts [19, 20].

We address this gap in community-based implementation science by describing a consensus modeling approach used to develop the farmers’ market PSE readiness assessment and decision instrument (FM PSE READI), a diagnostic tool for regularly assessing readiness and capacity to implement farmers’ market interventions among practitioners working with low-income populations in diverse contexts. We first describe methods to gain consensus from community residents and practitioners about the variety and importance of different factors influencing farmers’ market implementation. Next, we describe the iterative process of integrating community feedback into a user-friendly diagnostic tool.

METHODS

Participants

Over 200 stakeholders in Ohio participated in the process of consensus modeling used to develop the FM PSE READI. These stakeholders included county- and state-level public health and community nutrition practitioners, community residents including people receiving federal food assistance benefits, experts in farmers’ market programming including farmers’ market managers and cooperative extension agents, and academics. In particular, the public health practitioners were supported through a state-wide program, Creating Healthy Communities (CHC), organized by the Ohio Department of Health. The community nutrition practitioners worked within SNAP-Ed, a national program funded by the USDA and implemented within states to improve the likelihood that persons eligible for SNAP will make healthy choices within a limited budget and choose active lifestyles [1].

Consensus modeling process

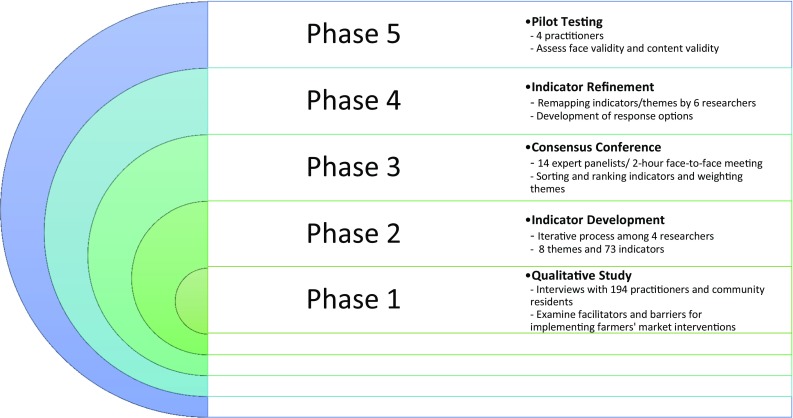

A multiphase, consensus modeling approach was used to capture diverse perspectives and shared beliefs about factors influencing farmers’ market implementation within communities [16–18]. As depicted in Fig. 1, the process of consensus development can be summarized into five phases: (1) qualitative study with community stakeholders, (2) development of indicators, (3) consensus conference, (4) indicator refinement, and (5) pilot testing.

Fig. 1.

Five-phase consensus modeling process for developing assessment tools of community readiness and capacity for implementing farmers’ market interventions

Phase 1: qualitative study with community stakeholders

Between April and June 2015, we conducted in-person and focus group interviews with community stakeholders in nine counties (five urban, four rural) across Ohio. The interviews were semi-structured and open-ended based on interview guides developed by the research team (see Appendices 1 and 2 for interview and focus group guides). The interviews lasted between 1 and 2 h, including time necessary to review consent forms. All interviews were conducted in English by two trained researchers and audio-recorded for transcription.

Purposive sampling was used to recruit participants [21]. First, nine counties in Ohio were targeted for recruitment because they had on-the-ground CHC and SNAP-Ed staff to support PSE implementation. These nine counties also represented diversity in terms of county health ranking, geographic location, adult obesity rates, and SNAP participation. Within each of these counties, two participant groups were included. The first were frontline practitioners working with the CHC or SNAP-Ed programs; these individuals were recruited by email. The second participant group included community members receiving or eligible to receive federal food assistance benefits and members of CHC coalitions organized within the targeted counties. Community members were recruited through flyers posted within public spaces or at CHC coalition meetings in the targeted communities; interested participants called the study phone line to learn about the study and, if interested, sign up for a focus group. All participants provided written informed consent to join the study.

Analysis began immediately after data collection. Data were transcribed verbatim and analyzed by researchers using qualitative data analysis software, Atlas ti. (version 7). A modified grounded theory approach was used to develop the coding structure [22]. First, line-by-line reading of the data guided the development of open codes to authentically represent the participants’ own words and capture emerging concepts. Next, thematic coding was guided by a codebook developed based on existing theory related to community readiness and capacity for implementation of prevention interventions [13, 23] as well as the emergent codes. The researchers then linked the open codes to subthemes, and the subthemes were assigned to their respective themes. For instance, logistical factors represented a theme related to factors that are needed to coordinate the implementation of farmers’ market interventions with the following subthemes: convenience, transportation, cost, and space. Example open codes related to the convenience subtheme included: “Hours of operation is a barrier to utilize farmers’ markets” and “I like to shop there (farmers’ market), but it’s only between these hours and these hours and it’s not as convenient as a grocery store.” The themes that were most common across the interviews and focus groups were used to focus indicator development in phase 2.

Phase 2: development of indicators

The goal at phase 2 was to narrow down the list of themes and subthemes to focus on those mentioned most frequently by participants and operationalize themes and subthemes into potential indicators of farmers’ market implementation. We established a threshold to limit the qualitative data by focusing on themes with at least 50 unique reference across all data sources and subthemes that met a minimum prevalence threshold (1% of the total open codes) to focus on indicators more commonly identified as facilitators or barriers of farmers’ market implementation. Using the themes and subthemes that met the threshold, four research team members worked together to generate theme definitions and develop the indicators for farmers’ market implementation through an iterative process of discussion and refinement.

Phase 3: consensus conference

In the third phase, a 14-member expert panel was recruited to assess the relevance and importance of the indicators and themes for farmers’ market implementation. Panelists were recruited purposively because of their expertise in farmers’ market development and management, experience in community nutrition and public health practice, and/or experience working with low-income populations. The primary purpose of this process was to generate ideas, uncover controversial issues, and synthesize stakeholder opinions to ascertain legitimacy of the indicators for farmers’ market implementation [15–17].

The 2-h consensus conference involved five steps. First, the research team presented overall goals and rationale of the study, major findings of qualitative data, and introduction to the process of consensus development. Second, panelists were asked to work in small groups (two to three panelists per group) to conduct a pile sorting activity [24] to sort each indicator into the relevant theme pile. Operational definitions of each theme were provided prior to the pile sorting activity. Third, these groups rank-ordered indicators within each theme based on their relevance (in characterizing readiness with respect to the theme in question) for successful farmers’ market implementation. The research team recorded the results of the ranking conducted by the groups. Fourth, panelists were asked to individually assign weights to the themes through an interactive voting process. Panelists received 25 tokens and were asked to distribute all tokens based on importance and relevance of each theme for successful implementation of farmers’ market PSE interventions. Panelists recorded the number of tokens distributed to each theme on a worksheet. Finally, the research team recorded all the data from the two ranking activities into an excel spreadsheet and assigned weights to the top three indicators chosen by each group of the panelists (first choice = 3, second choice = 2, and third choice = 1). At the end of the consensus conference, the research team then presented a summary of findings to the expert panel.

Phase 4: indicator refinement

In the fourth phase, the research team met multiple times to discuss and refine the indicators based on findings and recommendations from the consensus conference in phase 3. The research team also identified indicators that could be combined because of similarities as well as indicators that should be excluded due to irrelevance or lack of clarity. When indicators were combined, the higher weight assigned by panelists in phase 3 was applied to the combined indicator. The next step in this phase was to reduce the number of potential indicators on the FM PSE READI to design a parsimonious assessment tool that will reduce participant burden while capturing significant variability related to farmers’ market implementation. For each respective theme, we determined the total weight (sum of indicator weights within the theme) of the indicators chosen in the consensus conference, and selected the highest-scoring indicators accounting for at least 80% of the total weight.

With the final theme weights (as per the token exercise), and with the final list of indicators within each theme (and their corresponding indicator weights), we then proceeded to define a hierarchical scoring algorithm for the FM PSE READI. At the top of this hierarchy was an overall readiness score (0–100 points), which was defined as a weighted sum of theme-specific readiness scores, using the theme weights. Similarly, at the next level of the hierarchy, the theme-specific readiness scores were defined as a weighted combination of indicator-specific scores for that theme, using the indicators’ weights.

Phase 5: pilot testing

Results from phases 1–4 were integrated to inform the development of the FM PSE READI tool for pilot testing with four new external expert panelists who might be potential end-users of this tool. The FM PSE READI was sent by email to these four panelists to ascertain face validity as well as content validity. These panelists included two CHC and two SNAP-Ed staff from four different counties in Ohio. Pilot testing included two steps. First, experts completed the FM PSE READI and noted areas of concern or ambiguity to guide refinement. Second, a phone interview was conducted to learn more about the relevance of the indicators, overall impression of the assessment tool, and suggestions for improvement. Feedback was recorded and discussed during research team meetings and informed additional refinement of the indicators and overall FM PSE READI instrumentation methods.

RESULTS

Phase 1: qualitative study with community stakeholders

Eighteen in-person interviews and 23 focus groups were conducted by a total of five researchers. In all, 194 participants completed either interviews (n = 20) or focus groups (n = 174). Of those who participated in the in-person interviews, 11 were CHC practitioners and 9 were SNAP-Ed practitioners. Focus groups included 127 community members and 47 CHC coalition members including people from public health departments, schools or childcare centers, and community-based organizations in the targeted counties. The majority (69%) of the focus group participants were female and 65% self-reported current receipt of federal food assistance benefits such as SNAP. Nearly 60% of participants in the focus groups self-reported they were white and 40% were African American. Due to confidentiality issues related to CHC and SNAP-Ed staff, demographics of interview participants were not recorded.

Phase 2: development of indicators

When the thresholds for themes and subthemes were applied, there were reductions in themes from 23 to 8 and subthemes from 70 to 30. These 8 themes and 30 subthemes resulted in the development of 73 indicators associated with successful implementation of farmers’ market interventions. These 73 indicators covered the 8 themes related to organizational capacity, practitioner awareness, practitioner attitudes and beliefs, networks and relationships, community perceptions, logistical factors, sustainability, and community food norms and skills.

Operational definitions for each theme were also developed. For example, the sustainability theme was defined as factors that increase the supply and demand of farmers’ market PSE projects. Using this definition, the theme was then operationalized into measureable indicators that captured different dimensions of the construct. For instance, four indicators were developed for sustainability related to successful implementation of farmers’ markets: “Are there enough farmers/vendors to support current and/or new farmers’ markets in your service area?”; “Have you or other partners in your community secured funding sources for healthy food incentive programs at farmers’ markets?”; “Are there programs in your service area to support increasing the number of farmers/vendors able to sell products at farmers’ markets?”; and “Are there incentive programs in your service area that target vulnerable populations (i.e., the elderly, people with disabilities, seniors, and people with diabetes)?”

Phase 3: consensus conference

Five groups of panelists participated in sorting indicators into their relevant themes. The expert panel also rank-ordered indicators for each theme based on their importance with regard to successful implementation of farmers’ market interventions. Weights ranged from 0 to 13. There were 16 indicators with weight scores of zero, which means none of the expert panelists ranked them for successful implementation of farmers’ market interventions. These indicators were excluded for further consideration resulting in 57 indicators remaining after this phase.

The theme weights assigned by each panelist based on the token allocation exercise ranged from 0 to 10. Total weights for each theme from all panelists ranged from 21 for “practitioner attitudes and beliefs” about farmers’ market PSE interventions to 42 for “organizational capacity” for farmers’ market implementation. The expert panel perceived that organizational capacity defined as the availability of budgets, human capital, and resources, and work plans was the most important factor for successful implementation of farmers’ market interventions among public health and community nutrition practitioners.

Phase 4: indicator refinement

Six researchers worked together to modify and remap indicators and themes and then developed response options for each indicator. The number of indicators reduced to 44 through this process. When we applied the 80% of cumulative indicator weight rule within each theme to create a parsimonious assessment tool, 14 indicators were excluded and the number of themes was reduced from 8 to 6 to better reflect the refined indicators. There were 30 indicators remaining after the refinement process. The 30 indicators had unique response options in this phase. For example, the indicator, “How familiar are you with steps involved with implementing healthy food incentive programs such as Double Up programs, prescriptions for healthy food, and/or coupons at farmers’ markets?” had a four-point Likert scale response option from “Not at all familiar” to “Very familiar.” The indicator, “My work plan for this year includes FM PSE projects,” had a “Yes” or “No” response option.

Phase 5: pilot testing

Findings and feedback from pilot testing guided further revisions of the FM PSE READI. First, the definitions for key terms were updated, and words and phrases that were unclear to the panelists were revised to promote clarity. Second, examples were added to indicators to clarify terms that panelists did not understand. Third, all indicators were revised using a common question and response options. Due to this change, the response options for all indicators were changed to a five-point Likert scale from “Not at all” (coded as 0.00) to “Extremely” (coded as 1.00) with a “Don’t know” option (coded as 0.00). Table 1 provides a summary of the final version of the FM PSE READI themes and indicators including their respective weights based on this consensus process.

Table 1.

Final Indicators and Weights for Farmers’ Market PSE Readiness Assessment and Decision Instrument (READI)

| FM PSE READI Themes and Indicators | Example Scoring using FM PSE READI | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theme | Standardized Theme Weight a | Indicator | Standardized Indicator Weight b | Example Indicator Response c | Weighted Indicator Score d | Maximum Possible Indicator Score e | Final Indicator Score f |

| Organizational and Practitioner Capacity | 0.23 | 1. To what extent does your organizational or program grant budget have sufficient funds to support FM PSE projects this year? | 0.42 | 0.50 | 4.83 | 9.66 | 4.83 |

| 2. To what extent does your current work plan include FM PSE projects? | 0.26 | 0.50 | 2.99 | 5.98 | 2.99 | ||

| 3. To what extent are you familiar with the steps involved with implementing healthy food incentive programs such as Double Up programs, prescriptions for healthy food, and/or coupons at farmers’ markets? | 0.16 | 0.75 | 2.76 | 3.68 | 0.92 | ||

| 4. To what extent do you spend time each month seeking out or connecting with community coalitions or professional networks to support implementation of FM PSE projects (such as food policy coalitions or healthy neighborhood coalitions)? | 0.16 | 0.25 | 0.92 | 3.68 | 2.76 | ||

| Practitioner Awareness and Perceptions | 0.14 | 5. To what extent are farmers' market managers in your service area informed about getting SNAP/EBT at their markets? | 0.14 | 0.25 | 0.49 | 1.96 | 1.47 |

| 6. To what extent would SNAP recipients and other low-income populations in your service area choose to shop at farmers' markets if SNAP was accepted? | 0.14 | 0.50 | 0.98 | 1.96 | 0.98 | ||

| 7. In the past year, to what extent did you assist at a farmers’ market in your service area on the development of consumer-friendly advertising about the health benefits of fruits and vegetables available for purchase at the farmers’ market(s)? | 0.11 | 0.75 | 1.16 | 1.54 | 0.38 | ||

| 8. In the past year, to what extent did you do outreach to educate farmers’ market staff about the food needs and interests of people receiving SNAP and other low-income populations? | 0.11 | 0.50 | 0.77 | 1.54 | 0.77 | ||

| 9. To what extent does your organization (CHC or SNAP-Ed) provide useful training (e.g., webinars, conferences) about healthy food incentive programs such as Double Up programs, prescriptions for healthy food, and/or coupons at farmers’ markets? | 0.08 | 0.75 | 0.84 | 1.12 | 0.28 | ||

| 10. To what extent have you been successful at getting SNAP/EBT approved at one or more farmers’ markets either on your own or through a partnership with another group or organization? | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.12 | 1.12 | ||

| 11. To what extent are there resources available in your community to educate people who run local farmers' markets about SNAP/EBT? | 0.08 | 0.25 | 0.28 | 1.12 | 0.84 | ||

| 12. To what extent do SNAP recipients and other low-income populations in your service area have the skills to use foods available at farmers’ markets? | 0.08 | 0.50 | 0.56 | 1.12 | 0.56 | ||

| 13. To what extent do farmers' markets in your service area provide community and economic benefits? | 0.08 | 0.75 | 0.84 | 1.12 | 0.28 | ||

| 14. To what extent are you confident in your ability to find useful resources and information to help guide farmers' market PSE project implementation? | 0.08 | 1.00 | 1.12 | 1.12 | 0.00 | ||

| Logistical Factors | 0.14 | 15. To what extent is it possible for SNAP recipients or other low-income populations in your service area to get to a farmers' market either through public transportation or by walking? | 0.5 | 0.50 | 3.50 | 7.00 | 3.50 |

| 16. To what extent are the prices at farmers’ markets in your service area affordable for people receiving SNAP benefits and other low-income populations? | 0.31 | 0.25 | 1.09 | 4.34 | 3.25 | ||

| 17. To what extent is there space available in high-traffic/highly visible areas in your service area for locating a farmers’ market? | 0.19 | 0.75 | 2.00 | 2.66 | 0.66 | ||

| Sustainability and Community Perceptions | 0.18 | 18. To what extent are there enough local farmers/vendors available to support farmers’ markets in your service area? | 0.33 | 1.00 | 5.94 | 5.94 | 0.00 |

| 19. To what extent are there agricultural development programs in your service area aimed at increasing the number of fruit and vegetable vendors at local farmers’ markets. (i.e., farmer training programs)? | 0.15 | 1.00 | 2.70 | 2.70 | 0.00 | ||

| 20. To what extent are people receiving SNAP benefits or other low-income populations in your service area motivated to use farmers’ markets? | 0.15 | 1.00 | 2.70 | 2.70 | 0.00 | ||

| 21. To what extent do vendors at farmers' markets in your service area sell fresh fruits and vegetables (versus other products like sweets, dairy, honey or crafts)? | 0.13 | 1.00 | 2.34 | 2.34 | 0.00 | ||

| 22. To what extent are the prices at local farmer’s markets comparable to prices at local supermarkets? | 0.13 | 1.00 | 2.34 | 2.34 | 0.00 | ||

| 23. To what extent do advertisements about farmers' markets in your service area include clear information about locations and hours of operation? | 0.08 | 1.00 | 1.44 | 1.44 | 0.00 | ||

| 24. To what extent do people receiving SNAP benefits or other low-income populations in your service area have positive perceptions about farmers’ markets? | 0.05 | 1.00 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.00 | ||

| Networks and Relationships | 0.20 | 25. To what extent are you connected to farmers’ market managers, OSU-Extension officers, farmer groups, or food policy coalitions who are supportive of implementing FM PSE projects? | 0.44 | 0.25 | 2.20 | 8.80 | 6.60 |

| 26. To what extent are you involved with or connected to other (CHC or SNAP-Ed) practitioners who are currently working on, or have worked on, a farmers’ market PSE project? | 0.31 | 0.50 | 3.10 | 6.20 | 3.10 | ||

| 27. In the past year, to what extent did you collaborate or partner with someone from another organization to work on FM PSE projects? | 0.25 | 0.75 | 3.75 | 5.00 | 1.25 | ||

| Community Food Norms | 0.12 | 28. To what extent are fruits and vegetables commonly consumed by your service population available at local farmers’ markets? | 0.52 | 0.50 | 3.12 | 6.24 | 3.12 |

| 29. In the past year, to what extent did you offer cooking classes focused on preparation of quick and easy meals using fresh fruits and vegetables available at local farmers’ markets? | 0.3 | 0.50 | 1.80 | 3.60 | 1.80 | ||

| 30. In the past year, to what extent did you distribute recipes that highlight foods available at local farmers’ markets? | 0.17 | 0.50 | 1.02 | 2.04 | 1.02 | ||

Notes.

FM = farmers’ market

SNAP = Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

EBT = Electronic Benefits Transfer

Total number of final indicators of FM PSE READI = 30

All calculations made using rounded numbers.

a Standardized final theme weights derived from consensus modeling methods on a range from 0 to 1.

b Standardized final indicator weights derived from consensus modeling methods on a range from 0 to 1.

cFor each indicator, scores were assigned to each response option on a scale from 0 to 1 with 0.00=Not at all, 0.25=Slightly, 0.50=Moderately, 0.75=Very, and 1.00=Extremely.

dWeighted indicator score is a product of the theme weight, indicator weight, and indicator response and then multiplied by 100 to calculate a score from 0 to 100.

eMaximum possible indicator score represents the weighted score with the maximum response (1.00) and is calculated as the product of the theme weight, indicator weight, and value of 1.00 and then multiplied by 100 to calculate a score from 0 to 100.

fFinal indicator score is the difference between the maximum possible indicator and the weighted indicator score. Higher scores indicate greater opportunity for improvement related to that specific indicator. The three highest final indicator scores marked in bold print will be used to derive tailored recommendations.

DISCUSSION

Nutrition-related PSE interventions such as farmers’ markets that improve behavioral settings (e.g., communities) and thereby influence heath behaviors are considered promising strategies to reduce chronic diseases especially among low-income populations [1, 10]. Recently, community nutrition practitioners who work in SNAP-Ed are now required to include these PSE strategies and interventions in their SNAP-Ed plans based on legislation in the Healthy Hunger Free Kids Act 2010 [1, 4, 10]. Still, implementation of these PSE interventions is complex and involves a variety of mechanisms [25–29]. Communities and organizations are at different levels of readiness and capacity. They are also in different social, cultural, and economic contexts as well as institutional settings that involve various stakeholders and their interactions [11–13]. As Glasgow and colleagues [27] noted, these contextual differences necessitate tailored implementation strategies based on the realities of community readiness and capacity. This type of tailoring may include preimplementation efforts to enhance general and innovation specific capacity to support future intervention success [23]. In the absence of assessment tools like the FM PSE READI, there is a risk that PSE intervention implementation will widen rather than narrow the health gap between communities because places with the greatest health need for the intervention (e.g., highest disease burden) may be least ready to support implementation while those with less need may have higher levels of readiness. The goal of the FM PSE READI is to assist communities in determining the next steps to promote farmers’ market implementation given existing resources and limitations. Ideally, readiness assessment tools will be used to target additional resources such as trainings, funding, and/or equipment that will be needed to promote equity in PSE implementation.

Our consensus modeling approach has implications for community-based implementation science. First, this is a first attempt to understand facilitators and barriers for successful implementation of farmers’ market interventions and to operationalize them into measureable indicators developed through a multiphase iterative process of consensus development among a variety of stakeholders. In particular, the heterogeneity of participants, including community residents, county- and state-level CHC and SNAP-Ed practitioners, CHC coalition members, and academics added to the richness of the discussion and reflection and increased the appropriateness of the assessment tool for use by practitioners in their planning efforts. Second, the face-to-face consensus conference proved to be a valuable process for assessing relevance and importance of indicators that were under consideration. This consensus conference contributed to the development of a conceptually sound set of indicators through panelists’ active engagement. It also provided an opportunity for new ideas and indicators to emerge through the iterative feedback process. Third, opportunities to pilot test the indicators by a new set of stakeholders allowed for assessment of the validity and applicability of the FM PSE READI by the intended end users. As a result, a total of six themes and their respective 30 indicators were finally developed through this multiphase iterative process of consensus modeling. These themes represent the following: organizational and practitioner capacity, networks and relationships, sustainability and community perceptions, practitioner awareness and perceptions, logistical factors, and community food norms.

The next step in this research is to transfer the FM PSE READI tool into a Web-based platform to support dissemination, quick assessment and feedback, and connections to resources that are tailored to different stages of readiness as well as to collect data to conduct internal validity and reproducibility tests within and across diverse contexts and diverse practitioners. The Web site will allow practitioners to complete the FM PSE READI individually or with a team. The ideal method for assessing readiness is the team approach because different community stakeholders may contribute different resources and perspectives that combine to support farmers’ market implementation [12, 13]. Practitioners will establish accounts with the FM PSE READI Web site to allow users to track their progress and review proposed recommendations at a later date. After completing the assessment, practitioners will receive three tailored recommendations based on the scoring algorithms generated through consensus modeling. Each recommendation will include links to existing resources to support practitioners.

The example in Table 1 illustrates responses from a hypothetical practitioner. The results of the FM PSE READI highlight the top three indicators that will be used to guide tailored recommendations including indicator 1, 15, and 25. The top three areas for improving readiness and capacity are derived by calculating the difference between the maximum possible indicator score and the weighted indicator score based on a practitioner’s response. Most other community readiness and capacity assessments derive scores by treating all indicators as equally important and relevant to implementation [30–32]. We are aware of one other readiness assessment tool focused on HIV/AIDS prevention that used a weighted algorithm similar to the method used in the FM PSE READI [33, 34].

The intention of the FM PSE READI is not simply to score or grade practitioners’ readiness to implement PSEs, but rather to use the tool to tailor recommendations commensurate with level of readiness. Practitioners may benefit from taking the FM PSE READI at any stage of their practice. For instance, in the early stages, the tool may yield recommendations to connect practitioners with key partners needed to implement farmers’ markets. These partners may come together and take the FM PSE READI as a group to assess their collective strengths and prioritize opportunities for improvement. FM PSE READI users will receive updated recommendations when they reevaluate themselves assuming prior recommendations were addressed. By using the FM PSE READI, practitioners are directed to evidence-based recommendations and resources tailored to local need. This creates a more efficient, standardized, and scalable method for accessing tailored resources.

Lastly, there are possible limitations inherent to the consensus modeling approach. First, the consensus modeling approach needs extensive time and efforts. Nevertheless, the modeling process is necessary to promote strong partnership and collaboration among key stakeholders to capture the complexity of community readiness and capacity for chronic disease prevention efforts in communities and develop tailored implementation strategies. Furthermore, this process supports buy-in from practitioners, which may facilitate utilization. Second, although participants were purposively selected to represent different stakeholders of farmers’ market interventions, they may not be representative of all perspectives. However, given the purposive method for recruiting diverse participants representing different rural and urban contexts, it is anticipated that the results of this research may be relevant to other contexts. Third, unlike other consensus techniques such as the Delphi method, we allowed expert panelists to interact and synthesize their expertise through a face-to-face consensus conference, which could result in potential bias introduced by interpersonal dynamics such as influence of dominant participants [14–17]. Fourth, regardless of level of experience, we applied equal weighting of all expert panelists’ opinions. We believe that this potential limitation was mitigated through extensive reflection and refinement among the research team as well as additional feedback from the pilot testing. In addition, it is possible that the indicators excluded because either panelists did not rate them or they were not within 80% of cumulative weights may be important for successful implementation of farmers’ markets. Our strategy for these indicators is to include the concepts in recommendations provided after practitioners complete the FM PSE READI. Finally, given we developed the indicators based on the findings of qualitative study with community stakeholders within the nine counties of Ohio, the FM PSE READI may not be applicable to counties excluded.

CONCLUSIONS

Successful implementation of nutrition-related PSE interventions such as farmers’ markets to reduce chronic disease burdens within communities requires first assessing community readiness and organizational capacity needed to support implementation. This study was an effort to systematically develop an assessment tool with a range of indicators of community readiness and capacity for farmers’ market implementation that can be used by practitioners in their planning efforts. This tool can help community nutrition and public health practitioners and policy makers to understand the complex factors associated with implementation of farmers’ markets and offer guidance to them for tailoring intervention delivery based on levels of community, practitioner, and organizational readiness and capacity.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 44 kb)

(DOCX 50 kb)

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful feedback, the participants involved in this research, and to Julie Hewitt, Nicole Vaudrin, and Andy Wapner for their research assistance.

Compliance with ethical standards:

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1975 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Funding

This study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Preventive Health and Health Services Block Grant, award number 2B01OT009042-15, and by the US Department of Agriculture Nutrition Education and Obesity Grant Program, award number G-1415-17-0847 and award number G-1617-0452, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Research Center supported by Cooperative Agreement Number 1U48DP005030.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict interest.

Footnotes

Implications

Practice: Implementation of community-based public health interventions should be guided by careful assessment of readiness and capacity to promote the uptake of the interventions within daily practice.

Policy: Tools that assess readiness and capacity for implementing community-based nutrition interventions are needed to facilitate the development of practice guidelines and public health policies.

Research: Future research is needed to examine whether implementation strategies tailored to a community’s level of readiness and capacity will foster success as well as sustainability of community-based nutrition interventions.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13142-017-0504-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.USDA . In: SNAP-Ed strategies and interventions: An obesity prevention toolkit for states. Agriculture USDo, editor. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture; 2013. p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pan L, Galuska DA, Sherry B, et al. Differences in prevalence of obesity among black, white, and Hispanic adults-United States, 2006–2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2009;58(27):740–744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peeters A, Barendregt J, Willekens F, Mackenbach JP, Mamun AA, Bonneu L. Obesity in adulthood and its consequences for life expectancy: A life-table analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2003;138(1):24–32. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-1-200301070-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.CDC . State indicator report on fruits and vegetable, 2009: national action guide. Atlanta, GA: Center for Disease Control and Prevention; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang X, Ouyang Y, Liu J, Zhu M, Zhao G, Bao W. Fruit and vegetable consumption and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: Systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMJ. 2014;349:g4490. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g4490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braveman PA, Cubbin C, Egerter S, Williams DR, Pamuk E. Socioeconomic disparities in health in the United States: What the patterns tell us. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(Suppl 1):S186–S96. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.166082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dutko P, Ver Ploeg M, Farrigan T. Characteristics and influential factors of food deserts. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zenk S, Schulz A, Hollis-Neely T, Campbell R, Holmes N, Watkins G, et al. Fruit and vegetable intake in African Americans; income and store characteristics. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2005;29(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stark JH, Neckerman K, Lovasi GS, Konty K, Quinn J, Arno P, et al. Neighbourhood food environments and body mass index among New York City adults. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013;67(9):736–742. doi: 10.1136/jech-2013-202354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khan LK, Sobush K, Keener D, Goodman K, Lowry A, Kakietek J, RR07 et al. Recommended community strategies and measurements to prevent obesity in the United States. MMWR. 2009;58:1–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edwards RW, Jumper-Thurman P, Plested BA, Oetting ER, Swanson L. Community readiness: Research to practice. Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28(97):291–307. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6629(200005)28:3<291::AID-JCOP5>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donnermeyer JF, Plested BA, Edwards RW, Oetting G, Littlethunder L. Community readiness and prevention programs. Journal of the Community Development Society. 1997;28(1):65–83. doi: 10.1080/15575339709489795. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oetting ER, Donnermeyer JF, Plested BA, Edwards RW, Kelly K, Beauvais F. Assessing community readiness for prevention. Int J Addict. 1995;30(6):659–683. doi: 10.3109/10826089509048752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Landeta J. Current validity of the Delphi method in social sciences. Technological Forecasting & Social Change. 2006;73:467–482. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2005.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kea B, Sun BC-A. Consensus development for healthcare professionals. International Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2015;10:373–383. doi: 10.1007/s11739-014-1156-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fink A, Kosecoff J, Chassin M, Brook RH. Consensus methods: Characteristics and guidelines for use. American Journal of Public Health. 1984;74(9):979–983. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.74.9.979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones J, Hunter D. Consensus methods for medical and health services research. BMJ. 1995;311:376–380. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7001.376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freedman DA, Whiteside YO, Brandt HM, Young V, Friedman DB, Hébert JR. Assessing readiness for establishing a farmers’ market at a community health center. Journal of Community Health. 2012;37(1):80–88. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9419-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Honeycutt S, Leeman J, McCarthy WJ, et al. Evaluating policy, systems, and environmental change interventions: Lessons learned from CDC’s prevention research centers. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2015;12. doi:10.5888/pcd12.150281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Freedman DA, Vaudrin N, Schneider C, et al. Systematic review of factors influencing farmers’ market use overall and among low-income populations. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2016;116(7):1136–1155. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2016.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tongco MDC Purposive sampling as a tool for informant selection. Ethnobotany Research and Applications. 2007;5:147–158. doi: 10.17348/era.5.0.147-158. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Charmaz K. Grounded theory: Methodology and theory construction. In N. J. Smelser, & P. B. Baltes (Eds.). International encyclopedia of the social and behavioral sciences. 2002:6369–6399.

- 23.Wandersman A, Duffy J, Flaspohler P, et al. Bridging the gap between prevention research and practice: The interactive systems framework for dissemination and implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;41(3-4):171–181. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9174-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ryan GW, Bernard HR. Techniques to identify themes. Field Methods. 2003;15(1):85–109. doi: 10.1177/1525822X02239569. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tabak RG, Khoong EC, Chambers DA, Brownson RC. Bridging research and practice: Models for dissemination and implementation research. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2012;43(3):337–350. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Colditz GA. The promise and challenges of dissemination and implementation research. In: Brownson R, Colditz G, Proctor EK, editors. Dissemination and implementation research in health: translating science to practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2012. pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glasgow RE, Vinson C, Chambers D, Khoury MJ, Kaplan RM, Hunter C. National institutes of health approaches to dissemination and implementation science: Current and future directions. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(7):1274–1281. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burke JG, Lich KH, Neal JW, Meissner HI, Yonas M, Mabry PL. Enhancing dissemination and implementation research using systems science methods. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2015;22(3):283–291. doi: 10.1007/s12529-014-9417-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mendel P, Meredith LS, Schoenbaum M, Sherbourne CD, Wells KB. Reference tools. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2007;35(1-2):21–37. doi:10.1007/s10488-007-0144-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10488-007-0144-9. Accessed July 11, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Beebe TJ, Harrison PA, Sharma A, Hedger S. The community readiness survey: Development and initial validation. Evaluation Review. 2001;25(1):55–71. doi: 10.1177/0193841X0102500103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feinberg ME, Riggs NR, Greenberg MT. Social networks and community prevention coalitions. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2005;26(4):279–298. doi: 10.1007/s10935-005-5390-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lempa M, Goodman RM, Rice J, Becker AB. Development of scales measuring the capacity of community-based initiatives. Health Education & Behavior. 2008;35(3):298–315. doi: 10.1177/1090198106293525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomas T, Narayanan P, Wheeler T, Kiran U, Joseph MJ, Ramanathan TV. Design of a Community Ownership and Preparedness Index: using data to inform the capacity development of community-based groups. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2012;66:ii26–ii33. doi: 10.1136/jech-2011-200590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Narayanan P, Moulasha K, Wheller T, Baer J, Bharadwaj S, Ramanathan TV, Thomas T. Monitoring community mobilisation and organizational capacity among high-risk groups in a large-scale HIV prevention programme in India: selected findings using a community ownership and preparedness index. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2012;66:ii34–ii4. doi: 10.1136/jech-2012-201065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 44 kb)

(DOCX 50 kb)