Abstract

The risk of gastric cancer (GC) remains even after H. pylori eradication; thus, other combination treatments, such as chemopreventive drugs, are needed. We evaluated the effects of aspirin on genetic/epigenetic alterations in precancerous conditions, i.e., atrophic mucosa (AM) and intestinal metaplasia (IM), in patients with chronic gastritis who had taken aspirin for more than 3 years. A total of 221 biopsy specimens from 74 patients, including atrophic gastritis (AG) cases without aspirin use (control), AG cases with aspirin use (AG group), and GC cases with aspirin use (GC group), were analyzed. Aspirin use was associated with a significant reduction of CDH1 methylation in AM (OR: 0.15, 95% CI: 0.06–0.41, p = 0.0002), but was less effective in reversing the methylation that occurred in IM. Frequent hypermethylation including that of CDH1 in AM increased in the GC group compared to the AG group, and CDH1 methylation was an independent predictive marker of GC (OR: 8.50, 95% CI: 2.64–25.33, p = 0.0003). In patients with long-term aspirin use, the changes of molecular events in AM but not IM may be an important factor in the reduction of cancer incidence. In addition, methylation of the CDH1 gene in AM may be a surrogate of GC.

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection causes non-atrophic gastritis, which progresses to atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia (IM), dysplasia, and finally, gastric cancer (GC)1. Thus, the International Agency for Research on Cancer has concluded that H. pylori is a class I human carcinogen2. To date, some meta-analyses have shown that H. pylori eradication reduced the risk of GC in patients with chronic gastritis who underwent endoscopic resection (ER) for early GC3–7. However, a recent study from Japan showed that even after H. pylori infection was cured and gastric inflammation was eliminated, there was still a risk of GC in the long-term8. Additionally, metachronous GC occurred to some degree in patients who had H. pylori infection eradicated following ER for early GC9–13. Thus, it remains controversial if H. pylori eradication suppresses the development of GC. To reduce the risk of GC after H. pylori eradication, other combination treatments such as anti-inflammatory agents and dietary or nutritional intervention are needed.

Some studies including meta-analyses have reported that aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are associated with a reduced risk of both colorectal cancer and GC14–17. Their anti-carcinogenetic effects have been attributed to inhibition of the cyclooxygenase pathway and their anti-inflammatory abilities18,19. The roles of a number of genetic and epigenetic alterations, including microsatellite instability (MSI) and promoter hypermethylation of multiple tumor-related genes, are reportedly involved in GC and precancerous conditions of the stomach20–33. The CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP), characterized by extensive hypermethylation of multiple CpG islands within the genome, is currently recognized as one of the major mechanisms in GC30. In addition, IM with a colonic phenotype, as detected by the Das-1 monoclonal antibody (mAb), was shown to be strongly associated with GC32–35. However, to date, no study has compared changes in molecular phenotype in patients with chronic gastritis with or without GC who have taken aspirin on a long-term basis.

It was recently reported that the risk of GC was reduced in patients who took aspirin on a regular basis for more than 3 years16. In this study, we examined the effects of aspirin on genetic and epigenetic alterations, as well as mAb Das-1 reactivity in precancerous conditions, i.e., atrophic mucosa (AM) and IM, in patients with chronic gastritis who regularly took aspirin for more than 3 years. We also determined the molecular markers linked to carcinogenesis risk in those patients. Finally, we compared the differences in molecular abnormalities between patients with AM and IM.

Results

Patient characteristics

The characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. The mean duration of aspirin use was 6.3 ± 2.7 years (range 3–15 years) in the atrophic gastritis (AG) group and 6.5 ± 3.4 years (3–15 years) in the GC group; thus there was no significant difference between groups. There was also no significant difference in mean age among the three groups, although there were more males in the GC group than in the controls (p = 0.002). H. pylori infection rate was not significantly different among the three groups; 24 individuals (75.0%) in the control group, 21 patients (87.5%) in the AG group, and 11 patients (61.1%) in the GC group were negative for H. pylori. Of these patients, 21 cases in the control group, 6 in the AG group and 3 in the GC group had undergone H. pylori treatment. The remaining 26 patients had not been treated for H. pylori infection; thus, their infection was considered naturally eradicated. Of these patients, severe mucosal atrophy (open type according to the endoscopic classification by Kimura and Takemoto)36 was identified in 66.7% (2 of 3) of cases in the control group, 60.0% (9 of 15) of cases in the AG group and in 75.0% (6 of 8) of cases in the GC group.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Control | AG group | GC group | P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 32 | n = 24 | n = 18 | |||||

| Past period aspirin use ± SD (yr) (range) | — | 6.3 ± 2.7 (3–15) | 6.5 ± 3.4 (3–15) | 0.67 | |||

| Medication | |||||||

| Low-dose aspirin | — | 20 | (83.3) | 18 | (100) | 0.12 | |

| NSAIDs | — | 4 | (16.7) | 0 | (0) | ||

| Mean age ± SD (yr) | 70.9 ± 8.4 | 73.0 ± 9.1 | 74.8 ± 5.9 | 0.25* | |||

| Male: Female | 14: 18 | 15: 9 | 16: 2 | a0.002 | |||

| H. pylori infection | |||||||

| Positive | 8 | (25.0) | 3 | (12.5) | 7 | (38.9) | 0.14 |

| Negative | 24 | (75.0) | 21 | (87.5) | 11 | (61.1) | |

| (Post-eradicated) | (21) | (6) | (3) | ||||

AG, atrophic gastritis; GC, gastric cancer; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

*Kruskal-Wallis test.

a P value comparing the control and GC groups.

MSI and epigenetic alterations

The incidence of MSI and hypermethylation of seven genes are shown in Tables 2, 3, 4 and 5. Most of the molecular alterations, with the exception of E-cadherin (CDH1) methylation, were more frequently found in IM compared to AM in each group (i.e., control, AG, and GC groups).

-

Molecular changes in AM by aspirin use

The methylation of CDH1 and methylated-in-tumor-31 (MINT31) in AM significantly decreased in the AG group compared to the control group (p < 0.0001 and p = 0.03, respectively). Multivariate analysis showed that aspirin use was associated with a significant reduction of CDH1 gene methylation (odds ratio [OR]: 0.15, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.06–0.41, p = 0.0002) (Table 2). In contrast, the frequency of methylation of CDH1 gene, and MINT1 and MINT31 loci significantly increased in the GC group (p < 0.0001, p = 0.02, and p = 0.004, respectively). Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that CDH1 methylation was an independent risk factor of significant gastric dysplasia (OR: 8.50, 95% CI: 2.64–25.33, p = 0.0003) (Table 3). Also, when adjusting for gender in multivariate analysis, a similar result was obtained (OR: 7.71, 95% CI: 2.34–25.42, p = 0.0008). The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of CDH1 methylation for the development of gastric dysplasia were 59%, 86%, 68%, and 80%, respectively.

-

Molecular changes in IM by aspirin use

The frequency of CIMP in IM significantly decreased in the AG group compared to the control group after aspirin use (p = 0.02) (Table 4). On the other hand, although CIMP rate tended to be higher in the GC group than in the AG group (p = 0.08), no significant differences in other molecular events between the two groups were found (Table 5).

Comparison of molecular events in AM and IM in different parts of the stomach in the AG and GC groups

Table 2.

Molecular changes in the AM - Comparison of molecular events between the control and AG groups.

| No. of biopsy specimens | Control | AG group | P | Multivariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 63 | (%) | n = 56 | (%) | OR (95% CI) | P | Gender-adjusted OR (95% CI) | P | ||

| MSI | 1 | (1.6) | 4 | (7.1) | 0.19 | ||||

| CIMP | 4 | (6.3) | 2 | (3.6) | 0.68 | ||||

| CDH1 | 34 | (54.0) | 8 | (14.3) | < 0.0001 | 0.15 (0.06–0.41) | 0.0002 | 0.12 (0.04–0.36) | 0.0001 |

| CDKN2A | 1 | (1.6) | 1 | (1.8) | 1 | ||||

| MLH1 | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 1 | ||||

| MGMT | 0 | (0) | 1 | (1.8) | 0.47 | ||||

| MINT1 | 11 | (17.5) | 5 | (8.9) | 0.19 | ||||

| MINT31 | 10 | (15.9) | 2 | (3.6) | 0.03 | 0.80 (0.14–4.86) | 0.80 | 0.93 (0.15–5.48) | 0.91 |

| RUNX3 | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 1 | ||||

AM, atrophic mucosa; AG, atrophic gastritis; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; MSI, microsatellite instability; CIMP, CpG island methylator phenotype.

Table 3.

Molecular changes in the AM - Comparison of molecular events between the AG and GC groups.

| No. of biopsy specimens | AG group | GC group | P | Multivariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 56 | (%) | n = 26 | (%) | OR (95% CI) | P | Gender-adjusted OR (95% CI) | P | ||

| MSI | 4 | (7.1) | 2 | (9.1) | 1 | ||||

| CIMP | 2 | (3.6) | 3 | (11.5) | 0.32 | ||||

| CDH1 | 8 | (14.3) | 17 | (65.4) | <0.0001 | 8.50 (2.64–25.33) | 0.0003 | 7.71 (2.34–25.42) | 0.0008 |

| CDKN2A | 1 | (1.8) | 0 | (0) | 1 | ||||

| MLH1 | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 1 | ||||

| MGMT | 1 | (1.8) | 0 | (0) | 1 | ||||

| MINT1 | 5 | (8.9) | 8 | (30.8) | 0.02 | 1.26 (0.24–6.55) | 0.78 | 1.32 (0.26–6.78) | 0.74 |

| MINT31 | 2 | (3.6) | 7 | (26.9) | 0.004 | 4.08 (0.55–30.32) | 0.11 | 4.30 (0.54–34.36) | 0.17 |

| RUNX3 | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 1 | ||||

AM, atrophic mucosa; AG, atrophic gastritis; GC, gastric cancer; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; MSI, microsatellite instability; CIMP, CpG island methylator phenotype

Table 4.

Molecular changes in the IM - Comparison of molecular events between the control and AG groups.

| No. of biopsy specimens | Control | AG group | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 33 | (%) | n = 16 | (%) | ||

| MSI | 5 | (15.2) | 2 | (12.5) | 1 |

| CIMP | 9 | (27.3) | 0 | (0) | 0.02 |

| CDH1 | 7 | (21.2) | 1 | (6.3) | 0.25 |

| CDKN2A | 1 | (3.0) | 0 | (0) | 1 |

| MLH1 | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 1 |

| MGMT | 0 | (0) | 1 | (6.3) | 0.33 |

| MINT1 | 23 | (69.7) | 12 | (75.0) | 1 |

| MINT31 | 16 | (48.5) | 8 | (50.0) | 1 |

| RUNX3 | 12 | (36.4) | 2 | (12.5) | 0.10 |

IM, intestinal metaplasia; AG, atrophic gastritis; MSI, microsatellite instability; CIMP, CpG island methylator phenotype.

Table 5.

Molecular changes in the IM - Comparison of molecular events between the AG and GC groups.

| No. of biopsy specimens | AG group | GC group | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 16 | (%) | n = 27 | (%) | ||

| MSI | 2 | (12.5) | 5 | (18.5) | 0.69 |

| CIMP | 0 | (0) | 6 | (20.0) | 0.08 |

| CDH1 | 1 | (6.3) | 4 | (13.3) | 0.64 |

| CDKN2A | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 1 |

| MLH1 | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 1 |

| MGMT | 1 | (6.3) | 1 | (3.3) | 1 |

| MINT1 | 12 | (75.0) | 19 | (63.3) | 0.52 |

| MINT31 | 8 | (50.0) | 14 | (46.7) | 1 |

| RUNX3 | 2 | (12.5) | 10 | (33.3) | 0.17 |

IM, intestinal metaplasia; AG, atrophic gastritis; GC, gastric cancer; MSI, microsatellite instability; CIMP, CpG island methylator phenotype.

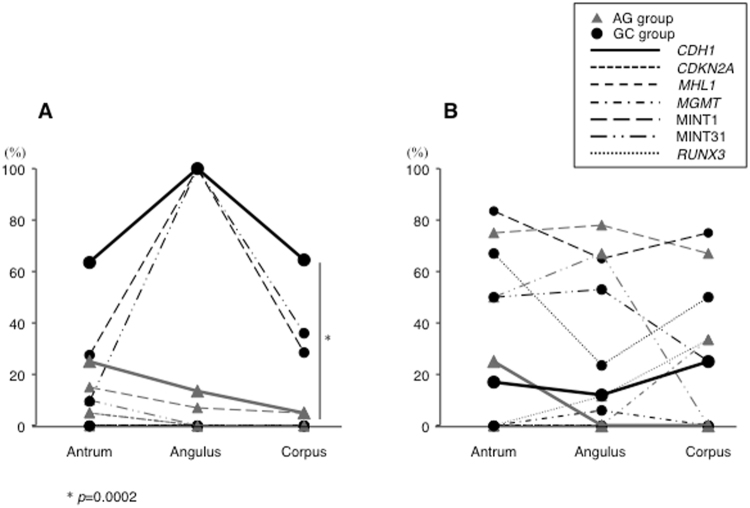

Methylation of CDH1, MINT1 and MINT31 in AM was observed in the stomach in both the AG and GC groups. Similarly, in IM, CpG island hypermethylation of most of the genes analyzed was identified in different portions of the stomach in both groups (Fig. 1A and B). The frequency of CDH1 methylation in AM was significantly higher in biopsy specimens taken from the greater curvature of the corpus in the GC group than in those from the AG group (p = 0.0002).

Figure 1.

CpG island methylation in precancerous conditions in three different parts of the stomach (antrum, angulus, and corpus). (A) In AM, hypermethylation of CDH1 gene, and MINT1 and MINT31 loci was observed throughout the stomach in the AG and GC groups. CDH1 methylation in AM, a predictive marker for gastric dysplasia, was significantly higher at the greater curvature of corpus in the GC group than in the AG group (p = 0.0002). (B) In IM, DNA hypermethylation of most genes other than CDH1 in the AG group and CDKN2A and MLH1 in the GC group was seen in the various portions of the stomach.

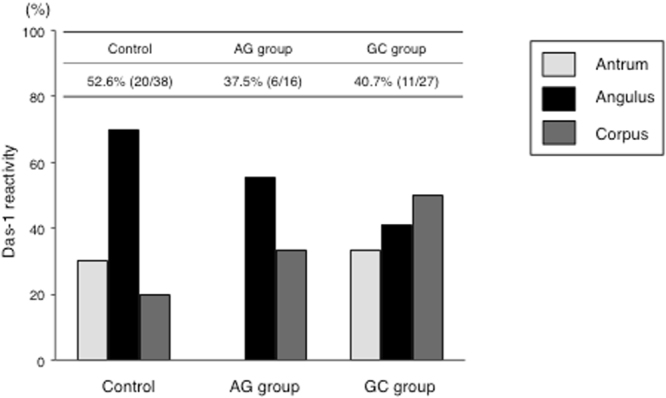

mAb Das-1 reactivity

There was no significant difference in reactivity to IM among the three groups (Fig. 2). However, mAb Das-1 reactivity against IM was highest in the angulus compared to the other portions of the stomach.

Figure 2.

mAb Das-1 reactivity to IM in different parts of the stomach in the three groups. mAb Das-1 reactivity was not different among the three groups, but reactivity in the GC group (40.7%) was lower than that in our previous studies32–35.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to show the effects of aspirin on molecular alterations related to carcinogenesis in patients with chronic gastritis with and without gastric dysplasia. The patients who regularly took aspirin were followed up to 15 years. Additionally, we evaluated the molecular differences between the two precancerous conditions of AM and IM, and identified biomarkers linked with gastric dysplasia risk. We found that long-term aspirin use was associated with a significant reduction of CDH1 methylation in AM and CIMP in IM, and that CDH1 methylation in AM was a significant biomarker for gastric dysplasia in patients taking aspirin.

H. pylori infection causes aberrant DNA hypermethylation of specific genes and induces CIMP, which is an important epigenetic mechanism of tumorigenesis37,38. Previous studies have reported that CDH1 methylation is strongly associated with H. pylori infection20,23–25, and it has been frequently observed in precancerous lesions20,24,25. Although several studies have demonstrated changes in DNA methylation after eradication of anti-H. pylori 23–27, no study has examined aberrant DNA methylation status in patients with chronic gastritis taking aspirin, especially taking into consideration the presence or absence of IM in atrophic gastritis. This study clearly demonstrated that the effects of aspirin in preventing of GC might be due to the reversal of aberrant methylation, as is the case with H. pylori eradication. Tahara et al.39 showed that chronic aspirin use was associated with a lower risk of CDH1 methylation in H. pylori-positive subjects, similar to the findings of our study. However, in that study, the duration of aspirin use was relatively short, and methylation status was only evaluated in biopsy specimens taken from the antrum. Moreover, the authors performed analysis of methylation status using methylation-specific PCR, which is prone to false-positive results and is qualitative. In contrast, the methylation-sensitive high resolution melting (MS-HRM) analysis used in our study is applicable for the sensitive and quantitative assessment of methylation levels in an unmethylated background33,40.

Interestingly, frequent aberrant hypermethylation was significantly increased in the GC group compared to the AG group, although most CpG island methylation was lower in the AG group than in the controls. Once methylation has occurred in a cell, it is difficult to conceive that demethylation can occur again in the same region (temporary methylation). Residual aberrant methylation, even after aspirin use, is thought to reflect methylation in gastric gland stem cells (permanent methylation)41; thus, individuals with residual methylation may be at risk of GC. Although the disappearance of CDH1 methylation is important for preventing the development of GC20,23–26, CDH1 methylation that persists after long-term aspirin use may be a surrogate marker of GC.

In this study, the number of genes that changed from methylated to unmethylated after aspirin use was higher in AM than in IM, indicating that aspirin was less effective in reversing the methylation that occurred in IM compared to AM. One reason for this difference may be the methodology of DNA extraction between AM and IM; DNA from AM was extracted from whole biopsy tissues with inflammatory cells, whereas DNA from IM was only extracted from IM glands using laser microdissection. Thus, the decrease in methylation levels observed in AM specimens is probably due to cell turnover caused by the anti-inflammatory effects of aspirin (temporary methylation)41. Although both AM and IM are considered to be precancerous conditions and important risk factors for GC42–45, it is not known as which lesion has advanced potential for GC44,46. Our study showed that all molecular events except CDH1 methylation were more frequently observed in IM than in AM, indicating that IM might have a more aggressive state than AM with regard to molecular alterations. Taken together, these results are in agreement with the concept of “point of no return”47, in which the benefits of aspirin diminish after the development of IM accompanied with molecular changes.

The accumulation of aberrant DNA methylation in non-cancerous tissues was recognized as “epigenetic field for cancerization”, especially in inflammation-associated cancers such as GC38,41,48,49. In this study, methylation was analyzed in biopsy specimens taken from three different parts of the stomach, as in the study by Perri et al.25. Most of the molecular alterations other than cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A) and MLH1 gene methylation were identified particularly in IM in the AG and GC groups for all portions of the stomach, which strongly supports the concept of “epigenetic field for cancerization”. Furthermore, the frequency of CDH1 methylation in AM, a biomarker of GC in our study, at the greater curvature of the corpus was significantly higher in the GC group than in the AG group, suggesting that CDH1 methylation in biopsies from this region is a potential biomarker of GC.

In this study, no MLH1 methylation was seen in the background mucosa with MSI. We did not analyze MSH2 and other DNA mismatch repair (MMR) genes; therefore, alterations in MMR genes except MLH1 methylation may be associated with the mechanism underlying MSI in the precancerous lesions. We demonstrated that long-term aspirin use decreased CIMP in IM. CIMP is commonly considered to be a phenotype of GC30,37,38, and H. pylori infection causes aberrant DNA hypermethylation of specific genes and induces CIMP, an important epigenetic mechanism of gastric tumorigenesis38. However, there is little evidence of CIMP in precancerous lesions, although a study showed that CIMP status in GCs did not correlate with methylation levels in the background gastric mucosa50. Therefore, we investigated CIMP, which exhibits widespread CpG island methylation, in precancerous lesions.

We previously reported highly significant reactivity of mAb Das-1 against IM in GC patients compared to IM from non-cancer patients32–35. In addition, H. pylori eradication did not reduce the histologic IM score, but rather, changed the cellular phenotype of IM as identified by this mAb. In this study, immunoreactivity against mAb Das-1 in the GC group was relatively lower (40.6%) than that shown in our previous study (58–82%)32–35. This phenomenon may indicate that aspirin causes changes in colonic phenotype in GC patients. However, the results showed that GC developed even in the presence of reduced Das-1 reactivity, indicating that other neoplastic biomarkers including epigenetic alterations in addition to changes in cellular phenotype seem likely to underlie GC. In our previous studies32,33,35, we evaluated mAb Das-1 reactivity in biopsy specimens obtained from the greater curvature of the antrum and corpus. In this study, mAb Das-1 reactivity in the control group was similar to that in our previous reports when evaluating samples taken from those two regions; however, reactivity at the angulus was higher than that in the other two parts.

There were some limitations in this study. First, this was a study from a single institution with a small number of patients. Second, this was a cross-sectional study, which inevitably includes various types of biases. However, a randomized prevention trial to determine the preventive effects of aspirin in GC may be impossible due to the cost, time, and risk of adverse events such as gastrointestinal bleeding.

In conclusion, we found that long-term use of aspirin for more than 3 years decreases CDH1 methylation in AM and CIMP in IM, and that methylation of the CDH1 gene in AM is a surrogate marker of GC in patients regularly taking aspirin. In addition, IM might be more aggressive than AM with regard to molecular alterations. Our results indicate that changes in molecular events may explain the chemopreventive effects of aspirin in decreasing the incidence of GC. A prospective study in patients who are at “high risk” for GC is needed.

Patients, Materials, and Methods

Patients

We conducted a cross-sectional study between March 2011 and December 2016 enrolling consecutive patients with dysplasias comprising gastric adenomas or other GCs who received endoscopic resection (ER) at Hyogo College of Medicine Hospital (Hyogo, Japan). During this period, 522 consecutive patients with a total of 615 dysplasias comprising gastric adenomas (n = 50) and other GCs (n = 565) were treated with ER. Among them, 22 patients (4.2%) who had taken aspirin or NSAIDs for more than 3 years developed primary gastric dysplasia. However, because 4 of these 22 patients refused to enroll in this study, the finally study population comprised 18 patients in the GC group. The histology of these 18 primary gastric dysplasias was adenoma in 2, well differentiated-type in 13, moderately differentiated-type in 2, and poorly differentiated-type adenocarcinoma in 1. We analyzed these 18 patients who had developed primary gastric dysplasia despite taking low-dose aspirin (100 mg/day) or NSAIDs for more than 3 years (GC group); patients with histologically atrophic gastritis who regularly took low-dose aspirin or NSAIDs for more than 3 years (AG group); and patients with atrophic gastritis who did not take aspirin between October 2015 and December 2016 (control group). We used the criteria of the Japanese Research Society for Gastric Cancer51 as the histological criteria in this study. Patients with a history of esophagectomy or gastrectomy were excluded.

Consent and institutional review board

Written informed consent was obtained from all of the patients prior to this study. The Ethics Committee of Hyogo College of Medicine approved this study (Nos Rin-Hi 136 and 300). This trial is registered with the UMIN Clinical Trials Registry (No. UMIN000021857). The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

H. pylori status and DNA extraction

During each patient’s endoscopy, three biopsy specimens were taken from the greater curvatures of the antrum and corpus and the lesser curvatures of the angulus (one from each site). Each biopsy specimen was used for histologic examination by hematoxylin and eosin staining, Giemsa staining, mAb Das-1 staining, and DNA extraction. H. pylori status was analyzed in each patient with the following methods: urea breath test, Giemsa staining, and the E-plate anti-H pylori IgG antibody test (Eiken Kagaku, Tokyo, Japan). A patient was regarded as H. pylori-positive if the result of at least one of the three aforementioned methods was positive. From the paraffin-embedded biopsy specimens, two or three 7 µm thick tissue sections were cut for DNA extraction. DNA was extracted from goblet IM (incomplete type) using the QIAamp DNA Micro Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Goblet IM was isolated using the PALM MicroBeam laser microdissection system (Microlaser Technologies, Munich, Germany) to avoid DNA contamination of inflammatory or stromal cell nuclei32,33 (Supplementary Fig. S1). In contrast, DNA from AM without IM was extracted from whole biopsy tissues, and as such, these samples might have contained inflammatory cells. One sample obtained from the angulus in the GC group could not be analyzed for molecular alterations due to the small amount of DNA extracted from the biopsy specimen. Finally, a total of 221 biopsy samples from 74 patients were analyzed in this study. In this cross-sectional study, we investigated molecular events including MSI, methylation of CpG islands of various genes, CIMP, and mAb Das-1 reactivity.

Analysis of MSI by high-resolution fluorescent microsatellite analysis

As previously reported32,33,47, we examined the following five microsatellite loci on chromosomes for MSI based on the revised Bethesda panel52: BAT26, BAT25, D2S123, D5S346, and D17S250. The PCR products were evaluated for MSI by capillary electrophoresis using an ABI 3130xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and automatic sizing of the alleles using a GeneMapper® Ver. 4.0 (Applied Biosystems). The MSI status was judged according to previous reports40,53,54 (Supplementary Fig. S2). In cases that were indistinguishable between MSI and loss of heterozygosity54, the allelic imbalance (AI) ratio was calculated. MSI was determined to be positive when the AI ratio (normal allele 1:normal allele 2/tumor allele 1:tumor allele 2) was <0.67 or >1.35, as previously reported40,53 (Supplementary Fig. S2). Lesions were defined as MSI in two or more of the five investigated markers40.

Sodium bisulfite modification of DNA and CIMP markers

Similar to previous reports33,40, purified DNA samples were chemically modified by sodium bisulfite with an EpiTect® Fast Bisulfite Kit (Qiagen). The bisulfite-modified DNA was amplified using primer pairs that specifically amplify the methylated or unmethylated sequences of several genes/loci related to carcinogenesis including CDH1, CDKN2A (p16), MLH1, MINT1, MINT31, O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT), and runt-related transcription factor 3 (RUNX3). Although there are two major CIMP panels, the classic panel includes MINT1, MINT2, MINT31, CDKN2A, and MLH1 55; and the novel marker panel includes CACNA1G, IGF2, NEUROG1, RUNX3, and SOCS1 56. There is no gold standard with respect to gene panels and the number of marker thresholds used to define CIMP57. CIMP status generally implies methylation in at least two MINTs or target genes such as p14, p16, or MLH1 when a small panel of markers is needed58,59. Therefore, we analyzed CIMP with use of the seven panels based on our previous report40.

MS-HRM

We performed MS-HRM analysis as previously described33,40. Briefly, PCR amplification and MS-HRM analysis were performed using a LightCycler® 480 System II (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). The primer sequences of all genes for the methylated and unmethylated forms and PCR and MS-HRM conditions are summarized in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2. Percentages of methylation (0%, 10%, 50%, and 100%) were used to make the standard curve (Supplementary Fig. S3). In this study, only samples with >10% methylation were considered methylated. CIMP was defined as ≥3/7 methylated markers using the seven-marker CIMP panel.

Immunoperoxidase assays with mAb Das-1

Serial sections were stained with the mAb Das-1 (a highly specific IgM mAb against the colonic phenotype), which does not react with normal gastric mucosa and atrophic mucosa other than IM, using sensitive immunoperoxidase assays as previously described32–35. Greater than 10% of IM glands stained with mAb Das-1 was considered positive expression (Supplementary Fig. S4).

Statistical analysis

Continuous and categorical data are reported as means and standard deviations (SDs) and frequencies with proportions, respectively. The data were assessed by the Mann-Whitney U-test for comparisons between two independent groups, by the Kruskal-Wallis test for comparisons among the three independent groups, and by the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test for comparisons of proportions. We developed logistic regression models to assess the effect of molecular markers for gastric dysplasia. Molecular markers with a p value < 0.1 in univariate logistic regression model were included in the multivariate logistic regression model, followed by backward selection. The effects of molecular markers were expressed by ORs and 95% CIs. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed with StatView version 5.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ms. Mayumi Yamada for her excellent technical assistance. This study was supported by funding from Hyogo Prefecture Health Promotion Association, 2017, Astellas Pharma Inc., EA Pharma Co., Ltd., and a research grant (RO1DK63618 to K.M.D.) from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease, an institute within the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD, USA).

Author Contributions

J.W., and H.M. designed the study and analyzed the data; Y.M. J.W. and C.I. recruited the patients, performed DNA extraction, molecular analysis, immunohistochemistry, and analyzed the data; Y.M. J.W., K.H., T.Y., T.K., T.K., T.K., T.T., T.O., and H.F. performed endoscopy; T.M. performed statistical analysis, and K.M.D. provided mAb Das-1 and revised the manuscript; Y.M. and J.W. wrote the manuscript; H.M. revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the paper.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-017-13842-x.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Correa P, Piazuelo MB. The gastric precancerous cascade. J Dig Dis. 2012;13:2–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2011.00550.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.International Agency for Research on Cancer Schistosomes, liver flukes and Helicobacter pylori. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 1994;61:177–241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fuccio L, et al. Meta-analysis: can Helicobacter pylori eradication treatment reduce the risk for gastric cancer? Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:121–128. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-2-200907210-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoon SB, Park JM, Lim CH, Cho YK, Choi MG. Effect of Helicobacter pylori Eradication on Metachronous Gastric Cancer after Endoscopic Resection of Gastric Tumors: A Meta-Analysis. Helicobacter. 2014;19:243–248. doi: 10.1111/hel.12146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ford AC, Forman D, Hunt RH, Yuan Y, Moayyedi P. Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy to prevent gastric cancer in healthy asymptomatic infected individuals: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2014;348:g3174. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g3174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fukase K, et al. Japan Gast Study Group. Effect of eradication of Helicobacter pylori on incidence of metachronous gastric carcinoma after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer: an open-label, randamised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372:392–397. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61159-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doorakkers E, Lagergren J, Engstrand L, Brusselaers N. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori and Gastric Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Cohort Studies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108(9):jdw132. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Take S, et al. Seventeen-year effects of eradicating Helicobacter pylori on the prevention of gastric cancer in patients with peptic ulcer; a prospective cohort study. J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:638–644. doi: 10.1007/s00535-014-1004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maehata Y, et al. Long-term effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on the development of metachronous gastric cancer after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kato M, et al. Scheduled endoscopic surveillance controls secondary cancer after curative endoscopic resection for early gastric cancer: a multicentre retrospective cohort study by Osaka University ESD study group. Gut. 2013;62:1425–1432. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi J, et al. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori after endoscopic resection of gastric tumors does not reduce incidence of metachronous gastric carcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:793–800. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.09.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bae SE, et al. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on metachronous recurrence after endoscopic resection of gastric neoplasm. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:60–67. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jung S, et al. Preventing metachronous gastric lesions after endoscopic submucosal dissection through Helicobacter pylori eradication. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:75–81. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bosetti C, Rosato V, Gallus S, Cuzick J, La Vecchia C. Aspirin and cancer risk: a quantitative review to 2011. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:1403–1415. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Algra AM, Rothwell PM. Effects of regular aspirin on long term cancer incidence and metastasis: a systematic comparison of evidence from observational studies versus randomised trials. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:518–527. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70112-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim YI, et al. Long-Term Low-Dose Aspirin Use Reduces Gastric Cancer Incidence: A Nationwide Cohort Study. Cancer Res Treat. 2016;48:798–805. doi: 10.4143/crt.2015.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cao Y, et al. Population-wide Impact of Long-term Use of Aspirin and the Risk for Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:762–769. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.6396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ulrich CM, Bigler J, Potter JD. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for cancer prevention: promise, perils and pharmacogenetics. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:130–140. doi: 10.1038/nrc1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sostres C, Lanas A. Gastrointestinal effects of aspirin. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8:385–394. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2011.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chan AO, et al. Promoter methylation of E-cadherin gene in gastric mucosa associated with Helicobacter pylori infection and in gastric cancer. Gut. 2003;52:502–506. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.4.502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kang GH, Lee S, Kim JS, Jung HY. Profile of aberrant CpG island methylation along the multistep pathway of gastric carcinogenesis. Lab Invest. 2003;83:635–641. doi: 10.1097/01.LAB.0000067481.08984.3F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maekita T, et al. High levels of aberrant DNA methylation in Helicobacter pylori-infected gastric mucosae and its possible association with gastric cancer risk. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:989–995. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leung WK, et al. Effects of Helicobacter pylori eradication on methylation status of E-cadherin gene in noncancerous stomach. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:3216–3221. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chan AO, et al. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection reverses E-cadherin promoter hypermethylation. Gut. 2006;55:463–468. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.077776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perri F, et al. Aberrant DNA methylation in non-neoplastic gastric mucosa of H. Pylori infected patients and effect of eradication. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1361–1371. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sepulveda AR, et al. CpG methylation and reduced expression of O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase is associated with Helicobacter pylori infection. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:1836–1844. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakajima T, et al. Persistence of a component of DNA methylation in gastric mucosae after Helicobacter pylori eradication. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:37–44. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0142-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dong CX, et al. Promoter methylation of p16 associated with Helicobacter pylori infection in precancerous gastric lesions: a population-based study. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:434–439. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li WQ, et al. RUNX3 methylation and expression associated with advanced precancerous gastric lesions in a Chinese population. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:406–410. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen HY, et al. High CpG island methylator phenotype is associated with lymph node metastasis and prognosis in gastric cancer. Cancer Sci. 2012;103:73–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.02129.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shin CM, et al. Changes in aberrant DNA methylation after Helicobacter pylori eradication: a long-term follow-up study. Int J Cancer. 2013;133:2034–2042. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Watari J, et al. Biomarkers predicting development of metachronous gastric cancer after endoscopic resection: an analysis of molecular pathology of Helicobacter pylori eradication. Int J Cancer. 2012;130:2349–2358. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kawanaka M, et al. Effects of Helicobacter pylori eradication on the development of metachronous gastric cancer after endoscopic treatment: analysis of molecular alterations by a randomised controlled trial. Br J Cancer. 2016;114:21–29. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mirza ZK, et al. Gastric intestinal metaplasia as detected by a novel biomarker is highly associated with gastric adenocarcinoma. Gut. 2003;52:807–812. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.6.807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Watari J, et al. Effect of eradication of Helicobacter pylori on the histology and cellular phenotype of gastric intestinal metaplasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:409–417. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kimura K, Takemoto T. An endoscopic recognition of the atrophic border and its significance in chronic gastritis. Endoscopy. 1969;3:87–97. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1098086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu JB, et al. CpG island methylator phenotype and Helicobacter pylori infection associated with gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:5129–5134. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i36.5129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zong L, Seto Y. CpG island methylator phenotype, Helicobacter pylori, Epstein-Barr virus, and microsatellite instability and prognosis in gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e86097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tahara T, et al. Chronic aspirin use suppresses CDH1 methylation in human gastric mucosa. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:54–59. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0701-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nando Y, et al. Genetic instability, CpG island methylator phenotype and proliferative activity are distinct differences between diminutive and small tubular adenoma of the colorectum. Hum Pathol. 2016;60:37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2016.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Enomoto S, et al. Novel risk markers for gastric cancer screening: Present status and future prospects. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;2:381–387. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v2.i12.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Busuttil RA, Boussioutas A. Intestinal metaplasia: a premalignant lesion involved in gastric carcinogenesis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:193–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rugge M, et al. Gastritis OLGA-staging and gastric cancer risk: a twelve-year clinico-pathological follow-up study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:1104–1111. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cho SJ, et al. Staging of intestinal- and diffuse-type gastric cancers with the OLGA and OLGIM staging systems. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:1292–1302. doi: 10.1111/apt.12515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee TY, et al. The Incidence of Gastric Adenocarcinoma Among Patients With Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia: A Long-term Cohort Study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50:532–537. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sasaki I, Yao T, Nawata H, Tsuneyoshi M. Minute gastric carcinoma of differentiated type with special reference to the significance of intestinal metaplasia, proliferative zone, and p53 protein during tumor development. Cancer. 1999;85:1719–1729. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19990415)85:8<1719::AID-CNCR11>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wong BC, et al. China Gastric Cancer Study Group. Helicobacter pylori eradication to prevent gastric cancer in a high-risk region of China: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:187–194. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maeda M, Moro H, Ushijima T. Mechanisms for the induction of gastric cancer by Helicobacter pylori infection: aberrant DNA methylation pathway. Gastric Cancer. 2017;20:8–15. doi: 10.1007/s10120-016-0650-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baba Y, et al. Epigenetic field cancerization in gastrointestinal cancers. Cancer Lett. 2016;375:360–366. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Enomoto S, et al. Lack of association between CpG island methylator phenotype in human gastric cancers and methylation in their background non-cancerous gastric mucosae. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:1853–1861. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00625.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Japanese Gastric Cancer Association Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma - 2nd English edition. Gastric Cancer. 1998;1:10–24. doi: 10.1007/PL00011681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Umar A, et al. Revised Bethesda Guidelines for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome) and microsatellite instability. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:261–268. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bryś M, et al. Diagnostic value of DNA alteration: loss of heterozygosity or allelic imbalance-promising for molecular staging of prostate cancers. Med Oncol. 2013;30:391. doi: 10.1007/s12032-012-0391-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Eto T, et al. Modal variety of microsatellite instability in human endometrial carcinomas. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2016;142:353–363. doi: 10.1007/s00432-015-2030-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Issa JP. CpG island methylator phenotype in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:988–993. doi: 10.1038/nrc1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weisenberger DJ, et al. CpG island methylator phenotype underlies sporadic microsatellite instability and is tightly associated with BRAF mutation in colorectal cancer. Nat Genet. 2006;38:787–793. doi: 10.1038/ng1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hughes LA, et al. The CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancer: progress and problems. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1825:77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rashid A, Issa JP. CpG island methylation in gastroenterologic neoplasia: a maturing field. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1578–1588. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jass JR, Whitehall VLJ, Young J, Leggett BA. Emerging concepts in colorectal neoplasia. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:862–876. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.35392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.