Abstract

Most known chemiluminescence (CL) reactions exhibit flash-type light emission. Great efforts have been devoted to the development of CL systems that emit light with high intensity and long-lasting time. However, a long-lasting CL system that can last for hundreds of hours is yet-to-be-demonstrated. Here we show firefly-mimicking intensive and long-lasting CL hydrogels consisting of chitosan, CL reagent N-(4-aminobutyl)-N-ethylisoluminol (ABEI) and catalyst Co2+. The light emission is even visible to naked eyes and lasts for over 150 h when the hydrogels are mixed with H2O2. This is attributed to slow-diffusion-controlled heterogeneous catalysis. Co2+ located at the skeleton of the hydrogels as an active site catalyzes the decomposition of slowly diffusing H2O2, followed by the reaction with ABEI to generate intensive and long-lasting CL. This mimics firefly bioluminescence system in terms of intensity, duration time and catalytic characteristic, which is of potential applications in cold light sources, bioassays, biosensors and biological imaging.

Great efforts have been devoted to the development of chemiluminescence systems that emit light with high intensity over long periods of time. Here the authors show, firefly-mimicking intensive and long-lasting chemiluminescence hydrogels consisting of chitosan, N-(4-aminobutyl)-N-ethylisoluminol (ABEI) and catalyst Co2+.

Introduction

Light emission induced by chemical reactions, known as chemiluminescence (CL), has been intensively investigated for many years. It has been widely applied in cold light sources, bioassays, reporter genes, biological imaging, and biomapping1–4. However, most known CL reactions exhibit flash-type light emissions, which hampers their applications. Light emission with high intensity and long-lasting time, i.e., glow-type emission, has been the holy grail of CL field. For example, strong and long-lasting emission are crucial for cold light sources in emergency situations, decorative entertainment, and underwater lighting. In analytical chemistry fields, the CL reactions with flash-type emission generally carry out CL emission in seconds or minutes and possess a fast kinetic curve, which would lead to poor analytical accuracy. The glow-type emission can produce a slow kinetic curve, even a constant emission within analytical time, which would improve greatly the analytical sensitivity and accuracy5. Besides, CL is less often used for imaging than fluorescence due to the lack of strong and long-lasting CL probes4, 6. Strong and long-lasting emission is beneficial for the investigation in the field of CL imaging with microscopy. In the past, enzyme-involved CL reactions are main CL systems producing long-lasting emission. For enzymatic reactions such as firefly bioluminescence (BL) system, bacterial BL system, alkaline phosphatase-3-(2′-spiroadamantane)-4-methoxy-4-(3″-phosphoryloxy)phenyl-1,2-dioxetane system and luminol-H2O2-peroxidases system, long-lasting emission arose from the turnover of the enzymes and excessive substrates7–9. However, enzyme inactivation was the main reason for light decay in the above CL systems10. Besides, peroxyoxalate ester CL system could also produce long-lasting emission under controlled conditions. The nucleophilic reaction of hydrogen peroxide with peroxyoxalate esters to generate a high energy intermediate dioxetandione is the rate-determining step for the CL reaction. The activated intermediate complex formed by dioxetandione and fluorophore can be continuously produced by succeeding supply of excess oxalate and fluorophore9. Since then, no new long-lasting CL mechanism has been discovered for a long time. Intensive and long-lasting CL emission is highly desired for sensitive and accurate bioassays, cold light sources and CL imaging, but is still a great challenge.

Herein, we report an intensive and long-lasting CL chitosan (CS) hydrogel with CL reagent N-(4-aminobutyl)-N-ethylisoluminol (ABEI) and catalyst Co2+ (ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogels) by virtue of a slow-diffusion-controlled heterogeneous catalytic mechanism, which mimics the firefly BL system in terms of both catalytic and kinetic characteristics. The light emission is even visible to naked eyes and lasts for over 150 h.

Results

Synthesis and characterizations

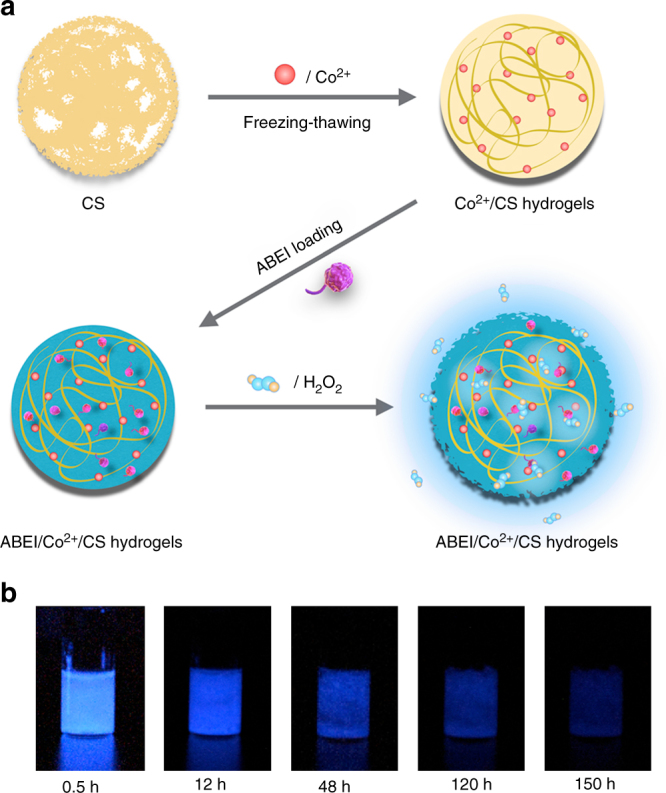

The preparation of ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogels is shown in Fig. 1a. Initially, chitosan powders dispersed in alkaline solution were mixed with CoCl2 solution. Through freezing-thawing process11, Co2+/CS hydrogels were obtained. Next, ABEI alkaline solution was mixed with Co2+/CS hydrogels and stirred to obtain ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogels. The as-prepared hydrogels were characterized by scanning electronic emission (SEM), rheology experiments, inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES) and UV-visible absorption spectra.

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration. a Preparation of ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogels. b CL emission of ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogels

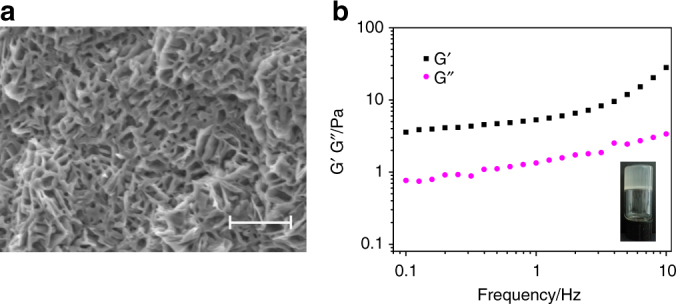

As shown in Fig. 2a, Co2+/CS hydrogels (10 times dilution) possessed porous sponge-like structure with lots of micro-sized and even nano-sized pores, which are consistent with those of previously reported CS hydrogel11, 12. The porosity of the hydrogels was determined to be 86%. The sponge-like structure with high porosity was endowed with high adsorption capacity for fluids. Moreover, these pores were effective channels for loading small molecules. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that this porous structure is a wonderful storage of small molecules. The viscoelastic properties of ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogels were studied by rheology experiments. After setting the strain amplitude at 1% (within the linear response of strain amplitude as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1), dynamic frequency sweep of ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogels was carried out. As shown in Fig. 2b, the dynamic storage modulus (G′) and loss modulus (G″) increased with the increase of the frequency from 0.1 to 10 Hz, and G′ was 3-4 times higher than G" at the same frequency. This is consistent with the observation that the materials possessed a gel-like structure that barely flowed (test tubes could be tilted upside down without sample flowing, see inset in Fig. 2b). Moreover, the CS hydrogels formed mainly by physical crosslinking13 are translucent, thus they are solvent-incompatible system. This is consistent with the fact that CS has a low solubility in alkaline aqueous solution14.

Fig. 2.

Characterization of Co2+/CS hydrogels and ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogels. a SEM images of freeze-dried Co2+/CS hydrogels with 10-folds dilution. Scale bar is 10 µm. b Frequency dependence of dynamic storage modulus (G') and loss modulus (G") of ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogels with 1 % strain at 20 °C. Inset in Fig. 2b: optical image of ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogels

The composition of the hydrogels was characterized. ICP-AES elemental analysis showed the existence of Co. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 2, the characteristic absorption peaks of pure ABEI appeared at around 290 and 320 nm. The Co2+/CS hydrogels did not have obvious characteristic absorption peaks. The two characteristic absorption peaks of ABEI at 291 and 320 nm were also observed in the UV/visible spectrum of ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogels, indicating the existence of ABEI molecules in ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogels. Therefore, both ABEI and Co2+ were successfully entrapped into the hydrogels. The ABEI and Co2+ used for synthesis were all trapped inside the hydrogels because no further separation treatment of the as-prepared hydrogels was conducted after synthesis.

CL performance

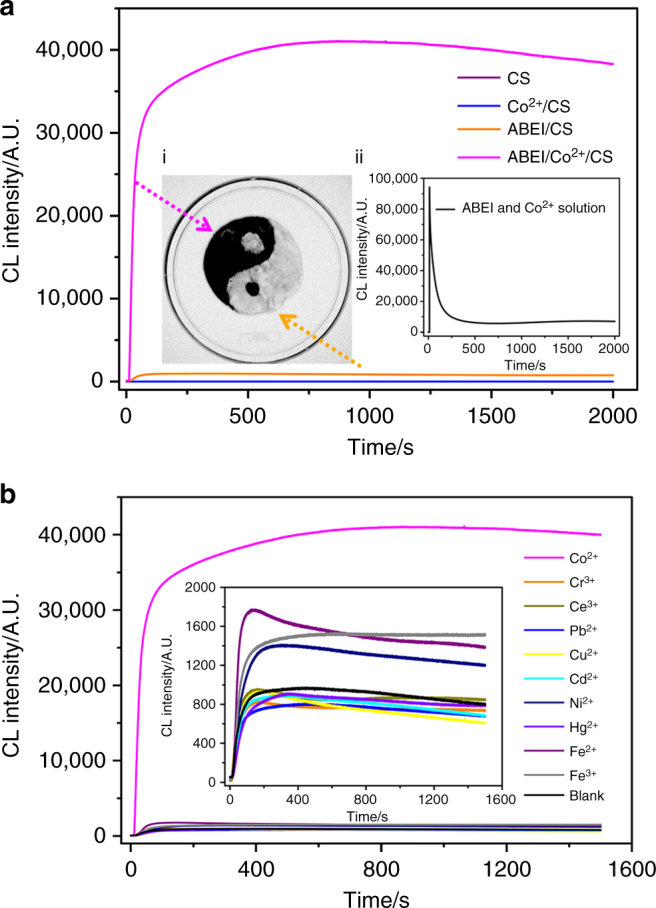

When ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogels reacted with H2O2 solution, firefly-mimicking intensive and long-lasting CL emission appeared, as shown in Fig. 1b. The light emission could be observed even by naked eyes in a dark room and lasted for over 150 h. The CL kinetic behavior of ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogels was further investigated by static injection as shown in Fig. 3a. 100 μl of the hydrogels was injected into 100 μl of 0.1 M H2O2 solution. Strong and long-lasting light emission was observed from ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogels (magenta curve), while no light emission from CS hydrogels (purple curve) and Co2+/CS hydrogels (blue curve). The CL spectrum of ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogels with H2O2 exhibited a peak centered at ~ 440 nm, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 3, which was consistent with that of the CL reaction of ABEI with H2O2 15. These results demonstrated that the CL reaction of ABEI with H2O2 was responsible for the light emission. Co2+ was further found to enhance the CL intensity by 40 times when comparing the CL intensities in the presence (magenta curve) and absence (orange curve) of Co2+. The CL signal of ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogels was not only strong, but also stable for over 25 min (the CL intensity only decreased to 93% of the maximum value in 25 min). The CL emission was recorded by gel CL imaging as shown in inset (i) of Fig. 3a. Based on the high contrast of ABEI/CS hydrogels and ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogels in CL intensity, traditional Chinese Taiji pattern was painted. ABEI/CS hydrogels showed a weak CL (white part) while ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogels a strong CL (black part). When Co2+ and ABEI solutions were directly mixed with H2O2 in alkaline solution, a flash CL emission was obtained as shown in inset (ii) of Fig. 3a. The CL reaction kinetic of the Co2+-ABEI-H2O2 system is quite different from those of ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogel-H2O2. The results demonstrated that the formation of hydrogels affected the CL reaction kinetic of Co2+- catalyzed ABEI-H2O2 system and played an important role in intensive and long-lasting CL. The stability of trapped ABEI and the sustainability of the hydrogel system were also studied by determining fluorescence intensity of ABEI and CL intensity of the hydrogels with H2O2 as functions of time, as shown in Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5. The results demonstrated that trapped ABEI and the hydrogels were stable in at least 30 days.

Fig. 3.

CL performance. a CL kinetic curves for reaction of CS hydrogels, Co2+/CS hydrogels, ABEI/CS hydrogels, ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogels with H2O2. Inset (i): gel CL imaging of ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogel-H2O2 (black) and ABEI/CS hydrogel-H2O2 (white). Inset (ii): CL kinetic curves for reaction of Co2+-ABEI-H2O2 system with a fixed photomultiplier tube (PMT) voltage of −450 V. b CL kinetic curves for reaction of ABEI/metal ion/CS hydrogels using different metal ions (Co2+, Cu2+, Pb2+, Ni2+, Hg2+, Cr3+, Ce3+, Cd2+, Fe2+, Fe3+ and blank) with H2O2. Inset: magnification of Cu2+, Pb2+, Ni2+, Hg2+, Cr3+, Ce3+, Cd2+, Fe2+, Fe3+ and blank (without metal ion) in the ABEI/metal ion/CS hydrogels-H2O2. Reaction condition: 100 μl 0.1 M H2O2, 100 μl hydrogels, -550 V PMT

The proposed long-lasting CL system is compared with other non-enzymatic and enzymatic CL systems. Peroxyoxalate esters and firefly BL are typical non-enzymatic and enzymatic CL systems for long-lasting CL emission, respectively. In the peroxyoxalate ester systems, light emission of bis(6-alkoxycarbonyl-2,4-dichlorophenyl) oxalates could last more than 12 h with low-intensity16. In firefly BL, typical emission could last for more than 6 h when firefly luciferase was in live cells and 2 h when firefly luciferase was in solution17, 18. The light emission of our CL system was even visible to naked eyes and lasted for over 150 h. Accordingly, our system have distinguished CL intensity and duration time, which superior to non-enzymatic peroxyoxalate ester CL system and enzymatic firefly BL system.

It has been reported that various metal ions could catalyze the CL reactions of luminol and its analogues with H2O2 19. Thus, instead of Co2+, other metal ions Cu2+, Pb2+, Ni2+, Hg2+, Cr3+, Ce3+, Cd2+, Fe2+ and Fe3+ were used to prepare the CS hydrogels. As shown in Fig. 3b, compared with ABEI/CS hydrogels without any metal ions, the CL intensity using Co2+, Fe3+, Fe2+, Ni2+, Ce3+, Cu2+, Hg2+, Cd2+, Cr3+ and Pb2+ changed by 4126, 82, 57, 45, −2, −4, −6, −8, −15, −17%, respectively. ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogels exhibited unique CL enhancement among all the tested metal ions. Other metal ions of Group VIII in periodic table also showed enhancement to some extent and the rest of the aforementioned ions did not significantly affect CL intensity. Therefore, the CL hydrogels using Co2+ are optimal for achieving intensive CL emission.

Optimization for CL conditions

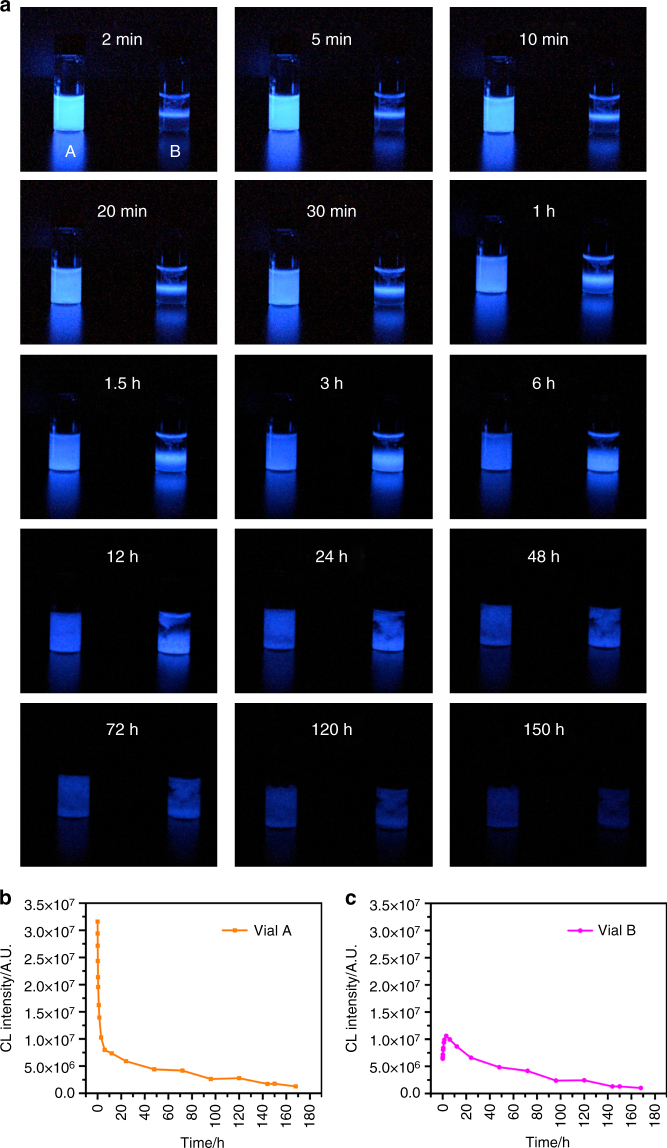

Some important parameters affecting the intensity and duration time of CL emission and the formation of the hydrogels, including the concentration of ABEI and Co2+, were studied. As shown in Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7, the CL intensity increased with the increase of ABEI and Co2+ concentrations. However, high Co2+ concentration was not favored for long-lasting time and hydrogel formation. Besides, it was also found that CL signal was highly dependent on the concentration of H2O2 (Supplementary Fig. 8). The CL intensity and the duration time increased with increasing the concentration of H2O2 up to 0.1 M. However, when the concentration of H2O2 was higher than 0.1 M, the CL intensity was slightly down and the CL was instable. It is possible that the oxygen bubbles due to H2O2 decomposition had an effect on the stability of the CL reaction. The effect of pH of H2O2 solution on the CL emission was studied in the pH range of 7.0–13.0. The CL emission could still be observed under neutral conditions. The CL intensities remained almost constant upon increasing pH values, and the optimal time for plateau emission was at pH 10.88 (Supplementary Fig. 9). Under optimal conditions, digital camera was used to record CL emission image in real time when H2O2 solution was either mixed fully with ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogels (Fig. 4a vial A) or added into ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogels directly (Fig. 4a vial B). Figures 4b, 4c also shows the CL intensity as a function of time over 150 h (the CL intensity was calculated as described in Supplementary Note 1). Both of cases showed intensive emission, which was even visible in a dark room with naked eyes. It is noteworthy that CL could last for more than 150 h. The CL spectra of ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogels with H2O2 at different times were also measured, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 10. No obvious change in CL spectra was observed.

Fig. 4.

Reaction of ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogels with H2O2 at different times. a Optical images using a digital camera. H2O2 solution was fully mixed with ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogels in vial A and H2O2 solution was directly added into ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogels without agitation in vial B. All the images are coded according to the same intensity scale. b, c CL intensity as a function of time for vial A and B, respectively. For ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogels, 40 mM 1.5 ml ABEI, 1 mM 0.6 ml Co2+, 15 ml CS dispersed in alkaline solution. Reaction condition: 1 ml 0.1 M H2O2, 1 ml hydrogels

Discussion

Such intensive and long-lasting emission of ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogels could be ascribed to the following reasons. As reported, metal ions, such as Co2+, could be highly adsorbed by chitosan by forming coordination bonds via hydroxyl and amine groups20, 21. Metal ions in the chitosan hydrogels could function as stabilizing linkages to prevent gel dissolution22. Thus, it may be suggested that Co2+ coordinates with the skeleton of the CS hydrogels and most of Co2+ exists in the CS phase. When the ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogels were centrifuged, Co2+ and ABEI concentration in supernatant were determined to be 6.41 × 10−5 and 3.14 mM, respectively, as shown Supplementary Table 1 and Note 2. Co2+ and ABEI concentration in ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogels were 3.51 × 10−2 and 3.51 mM, respectively. The results demonstrated that 0.18 % Co2+ and 89.48% ABEI existed in aqueous phase. Thus almost all of Co2+ was immobilized at the skeleton of the CS hydrogels. The porous network structure possessed micro/nano-sized pores and acted as a water-absorbing sponge, which allowed high concentration of ABEI to be loaded into the pores of the hydrogels. The uniform dispersion of ABEI in the porous network structure of hydrogels was confirmed by the fluorescence imaging of ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogels (Supplementary Fig. 11). Vial B in Fig. 4a shows the real-time reaction which involves adding 1 ml H2O2 solution onto the top of 1 ml hydrogels without further agitation. At the beginning, the CL reaction merely occurred at the interface between ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogels and H2O2 solution. Gradually, the H2O2 diffused into the hydrogels and more CL emission could be seen from the hydrogels. Due to the slow diffusion in hydrogels, it took 3–6 h for the top layer H2O2 to reach the bottom of the hydrogels (Fig. 4a, vial B), making the whole hydrogel lighting up. The slight degradation of the hydrogels was observed to produce some hydrogels fragments, which may speed up the diffusion and mixing process. Alternatively, if the hydrogels were fully mixed with H2O2 solution at first, CL emission appeared immediately in the entire bulk solution (Fig. 4a, vial A). The diffusion coefficient of H2O2 in the CS hydrogels was determined, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 12, Table 2 and Note 3. The results demonstrated that the diffusion coefficient of H2O2 in the CS hydrogels was more than one order of magnitude lower than that in a buffer solution, supporting the slow diffusion of H2O2 in hydrogels. The superior CL properties of the as-prepared hydrogels are derived from the synergistic effect of ABEI, Co2+ and porous network structure of ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogels. It is suggested that Co2+ located at the skeleton of CS hydrogels is active site of the CL reaction, which is surrounded by ABEI molecules in pores of the hydrogels. When H2O2 slowly diffuses to the active site, Co2+ as a catalyst would react with H2O2 to produce a highly reactive hydroxyl radical OH•, followed by the reaction with ABEI anion and HO2 – to facilitate the formation of ABEI radicals and O2 •–. Finally, ABEI radicals react with O2 •– to generate strong CL emission15. Because of the slow diffusion rate of H2O2 in hydrogels with high viscosity and micro/nano-sized pores, the CL reaction is a slow-diffusion-controlled process and could proceed for several days. Co2+ exhibited the strongest catalytic effect for the CL system, which may be due to that Co2+ complex demonstrated the strongest decomposition ability of hydrogen peroxide among transition metal ions23, 24 and was the best catalyst for luminol and its analogue CL reactions19. It was reported that Co2+ in the solutions showed very low catalytic activity for the decomposition of H2O2. Complexation and heterogenization of Co2+ enhance the catalytic activity of Co2+ on the decomposition of H2O2 25. It was also reported that the attachment of catalyst metal complex to a rigid polymer resulted in an increase in the catalytic activity and the stability of catalyst26, 27. This is because active site on the polymer was isolated and inactive reactions of catalyst metal ions in the homogeneous phase were prevented26, 27. Thus, in this case, Co2+ coordinated by hydroxyl and amine groups at the skeleton of CS hydrogels exhibited unique heterogeneous catalytic activity on the CL reaction, leading to intensive emission. The light emission could last for more than 150 h, implying that catalyst Co2+ could maintain catalytic activity for a long time. The excellent stability of catalyst Co2+ in the hydrogels may be due to the stabilization effect of polymer CS. Accordingly, high efficiency and excellent stability of catalyst Co2+ and the slow diffusion rate of H2O2 in hydrogels with high viscosity and micro/nano-sized pores resulted in the intensive and long-lasting CL emission. It is well known that firefly BL can produce intensive and long-lasting emission. Thus, the intensive and long-lasting CL emission from the hydrogels mimics firefly BL in terms of intensity and duration time. Since Co2+ was capable of maintaining catalytic activity for a long time and demonstrated high catalytic efficiency due to the hydrogels, the catalytic characteristic of Co2+ in our system are similar to those of enzyme associated with firefly BL17.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated firefly-mimicking intensive and long-lasting CL ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogels. The light emission could be observed even by naked eyes in a dark room and lasted for over 150 h when the hydrogels reacted with H2O2. The intensive and long-lasting CL emission was attributed to the synergistic effect of Co2+, ABEI and the porous network structure of the hydrogels through a slow-diffusion-controlled heterogeneous catalytic reaction. Using the low-concentration Co2+ as catalyst with high efficiency, CL emission of the as-prepared ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogels mimics firefly BL system in terms of intensity, duration time and catalytic characteristic. Such intensive and long-lasting CL emission with long-lasting mechanism is distinctly different from those of existing enzyme-involved CL and peroxyoxalate ester CL systems. The hydrogels can be used as cold light source in emergency situations, decorative entertainment, and underwater lighting. Compared with the commercial light sources whose emission duration can only reach 10-12 h, our hydrogels achieve a great improvement, which can produce CL emission for over 150 h. Our hydrogels are also environment-friendly and cost-effective. Moreover, the ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogels may find future applications in biosensors, microchips, bioassays and bioimaging, due to the hydrogel’s excellent biocompatibility28–31 and intensive and long-lasting CL emission.

Methods

Chemicals and materials

A 4.0 mM ABEI stock solution was prepared by dissolving ABEI (TCI, Japan) in 0.1 M NaOH solution. Chitosan (Mv > 1000 kDa, degree of deacytylation > 90%) was obtained from shanghai reagent (Shanghai, China). Working solutions of H2O2 were prepared fresh daily from 30% (v/v) H2O2 (Xin Ke Electrochemical Reagent Factory, Bengbu, China). All other reagents were of analytical grade. Ultrapure water was prepared by a Milli-Q system (Millipore, France) and used throughout. All glassware used in the following procedures was cleaned in a bath of freshly prepared HNO3-HCl (3:1, v/v), rinsed thoroughly with ultrapure water, and dried prior to use.

Synthesis of ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogels

Co2+/CS hydrogels were synthesized through the freezing-thawing method as previously reported with some modifications9. Chitosan powders were dispersed into 15 ml alkaline solution containing LiOH/KOH/urea/H2O in a ratio of 4.5: 7: 8: 80.5 by weight. 0.6 ml of CoCl2 (1, 5, 10, 20, 30 mM) was added to the above solution with stirring for 5 min, and then were stored under refrigeration until completely frozen. After that, the frozen solid was fully thawed. The Co2+/CS hydrogels with 2.5 wt% of chitosan were obtained. Next, 1.5 ml of ABEI (0.04, 0.4, 4 or 40 mM) was added to the Co2+/CS hydrogels and stirred for 5 h. Finally, the ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogels were obtained. The as-prepared Co2+/CS and ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogels were stored at 4 °C.

Characterization and property of ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogels

The as-synthesized hydrogels were characterized by SEM, rheological measurements, ICP-AES, inductively coupled plasma mass force microscopy (ICP-MS), UV-visible absorption spectra, microscope imaging, and CL spectra. For the SEM analysis, the Co2+/CS hydrogels were diluted 10 times with an alkaline solution containing LiOH/ KOH/urea/H2O with a ratio of 4.5: 7: 8: 80.5 by weight. The dilution was refrigerated to form frozen solid, then put into the lyophilizer under a condensing temperature of −50 °C and vacuum degree of 10 Pa. After 48 h, freeze-dried Co2+/CS hydrogels were obtained. A thin-layer of freeze-dried Co2+/CS hydrogels were deposited onto the conducting film. The morphology of the Co2+/CS hydrogels was measured by SEM. SEM images were obtained by a JEOL JEM-6700F microscope (Japan). The porosity of the hydrogels was calculated according to the equation: porosity = [(skeletal density-bulk density)/ skeletal density] × 100%32. Specifically, the ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogels were put in a bottle. After freeze-drying process as that in the treatment of the hydrogels for SEM, the weight of freeze-dried ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogels was 0.4122 g, and the volume was 2 cm3. Thus, the density of freeze-dried hydrogels (bulk density) was calculated to be 0.2061 g ml−1. 1 g of chitosan powders was added to 5 ml of ethanol in the graduated cylinder to obtain a solution with total volume of 5.7 ml (chitosan was not dissoluble in ethanol). Thus, the density of chitosan (skeletal density) was calculated to be 1.4286 g cm−3. Porosity could be computed according to above equation. Rheological measurements were conducted on a TA AR-G2 rheometer using a coneplate of 40 mm diameter with a cone angle of 1%. ICP-AES was obtained on an OPTIMA 7000DV atomic emission spectrometer. ICP-MS was measured on PlasmaQuad 3 Thermo VG (UK). UV-visible absorption spectra were obtained using UV-visible spectrophotometer (Agilent 8453, USA). CL spectra were measured on a model F-7000 spectrofluorophotometer when the Xe lamp was turned off (Hitachi, Japan). Fluorescence imaging was obtained on fluorescence microscope (Olympus DP72). CL gel imaging micrograph was performed on ChemiDoc XRS System (BIO-RAD, America). Digital photos were obtained on D7200 Nikon, and every picture was taken by using a delay of 30 s. The static injection CL detection was conducted on a BPCL Luminescence Analyzer (Beijing, China) with a fixed PMT voltage of -550 V. For a typical CL measurement, 100 μl of ABEI/Co2+/CS hydrogels was added to a cylindrical cell, then 100 μl of 0.1 M H2O2 in B-R buffer (pH = 10.88) was injected into the cell to initiate the CL reaction. The CL intensity during the reaction along with time was recorded by the luminescence analyzer.

Data availability

The authors declare that all the data are available within the article file and its Supplementary Information or from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The support of this research by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2016YFA0201300) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 21527807 and 21475120) are gratefully acknowledged. We thank Prof. K. Nakashima and Dr. E. Michelini for discussing the mechanism of peroxyoxalate ester CL system and firefly bioluminescence system. We are gratefully acknowledged for Prof. Y.X. Chen and Ms. J.J. Li to provide the experimental device for the measurement of diffusion coefficients of H2O2 in the hydrogels. We also thank Prof. Z.X. Deng for the discussion on diffusion coefficients, enzyme catalysis and the porosity of the hydrogels.

Author contributions

Y.L., W.S. and Q.L. contributed equally to this work. Y.L. and W.S. designed the project. Y.L. and Q.L. carried out the experimental work and writing of original draft. J.S. measured the diffusion coefficients of H2O2 in the hydrogels. W.W. and L.G. helped to complete the experimental work. M.M. was involved in studies on the long-lasting CL mechanism. W.S., J.S., W.W. and M.M. were also involved in writing of original draft. H.C. designed and directed the project and wrote the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Yating Liu, Wen Shen and Qi Li contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41467-017-01101-6.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Diaz JM, et al. Species-specific control of external superoxide levels by the coral holobiont during a natural bleaching event. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:13801. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clough JM, Balan A, van Daal TLJ, Sijbesma RP. Probing force with mechanobase-induced chemiluminescence. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:1445–1449. doi: 10.1002/anie.201508840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shuhendler AJ, Pu K, Cui L, Uetrecht JP, Rao J. Real-time imaging of oxidative and nitrosative stress in the liver of live animals for drug-toxicity testing. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014;32:373–380. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baumes JM, et al. Storable, thermally activated, near-infrared chemiluminescent dyes and dye-stained microparticles for optical imaging. Nat. Chem. 2010;2:1025–1030. doi: 10.1038/nchem.871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roda A, Guardigli M, Michelini E, Mirasoli M, Pasini P. Peer reviewed: analytical bioluminescence and chemiluminescence. Anal. Chem. 2003;75:463A–470A. doi: 10.1021/ac031398v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roda A, et al. Portable device based on chemiluminescence lensless imaging for personalized diagnostics through multiplex bioanalysis. Anal. Chem. 2011;83:3178–3185. doi: 10.1021/ac200360k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adams ST, Mofford DM, Reddy GSKK, Miller SC. Firefly luciferase mutants allow substrate-selective bioluminescence imaging in the mouse brain. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:4943–4946. doi: 10.1002/anie.201511350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hananya N, Boock AE, Boock CR, Satchi-Fainaro R, Shabat D. Remarkable enhancement of chemiluminescent signal by dioxetane–fluorophore conjugates: turn-on chemiluminescence probes with color modulation for sensing and imaging. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:13438–13446. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b09173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee D, et al. In vivo imaging of hydrogen peroxide with chemiluminescent nanoparticles. Nat. Mater. 2007;6:765–769. doi: 10.1038/nmat1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kapeluich YL, Rubtsova MY, Egorov AM. Enhanced chemiluminescence reaction applied to the study of horseradish peroxidase stability in the course of p-iodophenol oxidation. J. Biolumin. Chemilumin. 1997;12:299–308. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1271(199711/12)12:6<299::AID-BIO459>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duan J, Liang X, Cao Y, Wang S, Zhang L. High strength chitosan hydrogels with biocompatibility via new avenue based on constructing nanofibrous architecture. Macromolecules. 2015;48:2706–2714. doi: 10.1021/acs.macromol.5b00117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun GM, Zhang XZ, Chu CC. Formulation and characterization of chitosan-based hydrogel films having both temperature and pH sensitivity. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2007;18:1563–1577. doi: 10.1007/s10856-007-3030-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qu X, Wirsen A, Albertsson AC. Novel pH-sensitive chitosan hydrogels: swelling behavior and states of water. Polymer. (Guildf). 2000;41:4589–4598. doi: 10.1016/S0032-3861(99)00685-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsai TN, et al. Novel protein-loaded chondroitin sulfate-N-[(2-hydroxy-3-trimethylammonium) propyl] chitosan nanoparticles with reverse zeta potential: preparation, characterization, and ex vivo assessment. Mater. Chem. B. 2015;3:8729–8737. doi: 10.1039/C5TB01517K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu M, et al. Gold nanoparticles bifunctionalized by chemiluminescence reagent and catalyst metal complexes: synthesis and unique chemiluminescence property. Anal. Chem. 2014;86:2857–2861. doi: 10.1021/ac5002433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dowd CD, Paul DB. Synthesis and evaluation of diary1 oxalate esters for low-intensity chemiluminescent illumination. Aust. J. Chem. 1984;37:73–86. doi: 10.1071/CH9840073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ignowski JM, Schaffer DV. Kinetic analysis and modeling of firefly luciferase as a quantitative reporter gene in live mammalian cells. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2004;86:827–834. doi: 10.1002/bit.20059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feeney KA, Putker M, Brancaccio M, O’Neill JS. In-depth characterization of firefly luciferase as a reporter of circadian gene expression in mammalian cells. J. Biol. Rhythm. 2016;31:540–550. doi: 10.1177/0748730416668898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burdo TG, Seitz WR. Mechanism of cobalt catalysis of luminol chemiluminescence. Anal. Chem. 1975;47:1639–1643. doi: 10.1021/ac60359a019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang L, Zeng Y, Cheng Z. Removal of heavy metal ions using chitosan and modified chitosan: A review. J. Mol. Liq. 2016;214:175–191. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2015.12.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nie J, Wang Z, Hu Q. Difference between Chitosan Hydrogels via Alkaline and Acidic Solvent Systems. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41598-016-0001-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhattarai N, Gunn J, Zhang M. Chitosan-based hydrogels for controlled, localized drug delivery. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2010;62:83–99. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shi J, Lu C, Yan D, Ma L. High selectivity sensing of cobalt in HepG2 cells based on necklace model microenvironment-modulated carbon dot-improved chemiluminescence in Fenton-like system. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2013;45:58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2013.01.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin JM, Shan XQ, Hanaoka S, Yamada M. Luminol chemiluminescence in unbuffered solutions with a cobalt(II)-ethanolamine complex immobilized on resin as catalyst and its application to analysis. Anal. Chem. 2001;73:5043–5051. doi: 10.1021/ac010573+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shivankar VS, Thakkar NV. Decomposition of hydrogen peroxide in presence of mixed ligand cobalt (II) and nikel (II) complexes as catalysts. J. Sci. Ind. Res. 2005;64:496–503. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen C, Sun J, Li H, He B. Polymer effects on polymer-supported transition metal catalysts. Ion Exchange & Adsorption. 1991;7:227–236. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grubbs RH, Lau CP, Cukier R, Brubaker C. Polymer attached metallocenes. Evidence for site isolation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1977;99:4517–4518. doi: 10.1021/ja00455a059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seliktar D. Designing cell-compatible hydrogels for biomedical applications. Science. 2012;336:1124–1128. doi: 10.1126/science.1214804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ashley GW, Henise J, Reid R, Santi DV. Hydrogel drug delivery system with predictable and tunable drug release and degradation rates. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:2318–2323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215498110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kamata H, Akagi Y, Kayasuga-Kariya Y, Chung U, Sakai T. “Nonswellable” hydrogel without mechanical hysteresis. Science. 2014;21:873–875. doi: 10.1126/science.1247811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li J, Mooney DJ. Designing hydrogels for controlled drug delivery. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2016;1:1–17. doi: 10.1038/natrevmats.2016.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ferreiraa L, Gila MH, Cabritab AMS, Dordickc JS. Biocatalytic synthesis of highly ordered degradable dextran-based hydrogels. Biomaterials. 2005;26:4707–4716. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that all the data are available within the article file and its Supplementary Information or from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.