Abstract

AIM

To investigate the association between 16 insertion-deletions (INDEL) polymorphisms, colorectal cancer (CRC) risk and clinical features in an admixed population.

METHODS

One hundred and forty patients with CRC and 140 cancer-free subjects were examined. Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood samples. Polymorphisms and genomic ancestry distribution were assayed by Multiplex-PCR reaction, separated by capillary electrophoresis on the ABI 3130 Genetic Analyzer instrument and analyzed on GeneMapper ID v3.2. Clinicopathological data were obtained by consulting the patients’ clinical charts, intra-operative documentation, and pathology scoring.

RESULTS

Logistic regression analysis showed that polymorphism variations in IL4 gene was associated with increased CRC risk, while TYMS and UCP2 genes were associated with decreased risk. Reference to anatomical localization of tumor Del allele of NFKB1 and CASP8 were associated with more colon related incidents than rectosigmoid. In relation to the INDEL association with tumor node metastasis (TNM) stage risk, the Ins alleles of ACE, HLAG and TP53 (6 bp INDEL) were associated with higher TNM stage. Furthermore, regarding INDEL association with relapse risk, the Ins alleles of ACE, HLAG, and UGT1A1 were associated with early relapse risk, as well as the Del allele of TYMS. Regarding INDEL association with death risk before 10 years, the Ins allele of SGSM3 and UGT1A1 were associated with death risk.

CONCLUSION

The INDEL variations in ACE, UCP2, TYMS, IL4, NFKB1, CASP8, TP53, HLAG, UGT1A1, and SGSM3 were associated with CRC risk and clinical features in an admixed population. These data suggest that this cancer panel might be useful as a complementary tool for better clinical management, and more studies need to be conducted to confirm these findings.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, Ins-del polymorphism, Admixed population, Potential biomarker, Diagnostic, Risk stratification, Prognostic, Clinical features

Core tip: The insertion-deletions (INDEL) variations in IL4 gene was associated with increased colorectal cancer (CRC) risk, while TYMS and UP2 genes were associated with decreased risk. The Del-alleles of NFKB1 and CASP8 were associated with more colon related incidents than rectosigmoid. The Ins-alleles of ACE, HLAG and TP53 were associated with higher TNM stage. The Ins-allele of ACE, HLAG, and UGT1A1 were associated with early relapse risk, as well as the Del-allele of TYMS. The Ins-alleles of SGSM3 and UGT1A1 were associated with death risk. These data suggest that these INDEL might be useful as a complementary tool for better CRC clinical management.

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer type in men and the second in women, considering 1477402 new cases in both sexes in 2015[1]. In that same year, Brazil was the tenth country with the highest CRC incidence, with 37167 new cases in both sexes[1], and making matters worse, its incidence and mortality continue to increase in the country.

Both genetic and environmental factors cause CRC[2], especially when combined[3,4]. Interestingly, these factors are ample and they vary pursuant to the cancer geographical regions[5]. However, inherited susceptibility is a major component of CRC predisposition, with an estimated 12%-35% risk attributed to genetic factors[6-8].

In relation to genetic factors, there are several mutations that might occur in human DNA, such as substitution, insertion, and deletion[9]. The second most abundant form of genetic variation in humans, after single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), are the insertion-deletions (INDEL)[10]. INDELs are important because they are common genetic variations within genomes and among different ethnic groups[11,12], that may alter human traits and cause diseases[10,13], including CRC[14], by modifying the coding region[10,13] or mRNA stability[15]. The polymorphisms investigated in this study exhibit common features, given they are all functional polymorphisms that alter the expression of genes participating in metabolic pathways associated with carcinogenesis. Also, these genes are associated with different types of cancer with high incidence in the Brazilian population, such as stomach and CRC.

Furthermore, allele frequency varies among different populations[16], and genomic ancestry distribution may influence cancer development[17,18] by affecting polymorphisms distribution[19,20]. Few studies have been evaluated INDEL association in CRC in admixed population, mainly in Brazil. Thus, the aim of this study was to determine the association between CRC risk and prognostic follow-up with 16 INDELs in genes involved in apoptosis signaling (CASP8), GTPase-activating (SGSM3), steroids metabolism (CYP2E1, CYP19A1, and UGT1A1), immune system (HLAG, IL1A, IL4, and NFKB1), MDM2-P53 pathway (MDM2 and TP53), DNA replication and repair (TYMS and XRCC1) and angiogenesis (UCP2 and ACE) in an admixed population from Rio Grande do Norte state (in the Northeast Region of Brazil).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A statement of ethics

The protocol used in this study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Liga Norte Riograndense Contra o Câncer (Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil) by number 211/211/2011. Moreover, all participants signed a consent form prior to providing a blood sample.

Casuistic distinctions

The patients in the case group (n = 140) were diagnosed with CRC as primary cancer and treated in the Proctologist Clinic and Colorectal Surgery Department of Liga Norte Riograndense Contra o Câncer (Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil). The control subjects were cancer-free blood donors (n = 140) from the hemotherapy service (Hemovida, Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil) and were recruited in 2014.

Both Peripheral blood samples and questionnaire answers were collected from all subjects. The clinicopathological data were obtained by consulting the patients’ clinical charts, intra-operative documentation, and pathology scoring. Furthermore, the CRC patients were followed up to 20 years by medical records.

Definitions

Alcohol consumption was classified as having the habit of alcohol consumption (Yes) or not having the habit of alcohol consumption (No). The subjects who have the habit of consuming alcohol were subcategorized according to consumption frequency (Eventually: ≤ 3 d per month; Frequently: > 3 d per month). The tobacco consumption was classified as have already smoked (Already) or not (Never). The subjects who have already smoked were subcategorized in Former (Stopped smoking for at least 1 year) and Current.

Tumor location was classified as rectosigmoid (sigmoid colon and rectum) and colon (ascending, transverse and descending colon) based on colonoscopy or on radiographic exam. The relapse records were obtained from histological or radiographic exams with subsequent clinical/radiological progression.

Overall survival was defined as the time from the date of surgery to the date of death or the date of the last follow-up of patients who were still alive. The relapse time was defined as the time from the date of surgery to the date of the first local. Patients with no local or distant relapse evidence at the date of death or the date of the last follow-up were censored.

DNA extraction and quantification

Genomic DNA was extracted by using a DNA extraction commercial kit, QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), and quantified with Qubit® 2.0 Fluorometer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, United States).

Polymorphism selection

Recently, INDELs have been the focus of multiple investigations[21-25]. This type of polymorphism presents interesting features as genetic markers: (1) INDELs are spread throughout the human genome; (2) INDELs derive from a single event (they do not present homoplasy); (3) since the allele frequencies of many INDELs are significantly different in separated populations; (4) small INDELs can be analyzed using short amplicons, which improves the amplification of degraded DNA and facilitates multiplexing; and (5) INDELs can be easily genotyped with a simple dye-labeling electrophoretic approach. Furthermore, all these genes evaluated in the present study show potential activity in pathway and may contribute to the carcinogenesis process (Table 1). Their genetic variations could contribute to: (1) risk of developing CRC; (2) impact on treatment response; or (3) in prognosis.

Table 1.

Potential biological effects of insertion-deletions polymorphism selected in this study

| Gene | dbSNP | Localization1 | INDEL | Region | Potential biological effect[84] | Potential impact on carcinogenesis | |||

| lenght | mRNA splicing | mRNA stability | Gene expression | Protein function | |||||

| ACE | rs4646994 | 17:63488539 | 289 | Intron | X | X | X | Angiogenesis, proliferation, progression and metastases[85] | |

| CASP8 | rs3834129 | 2:201232809 | 6 | Promoter | X | Apoptosis[86-88] | |||

| SGSM3 | rs56228771 | 22:40410092 | 4 | 3'-UTR | X | X | Proliferation and apoptosis [83,89-91] | ||

| CYP2E1 | - | - | 96 | 5'-Flanking | X | Metabolism of endo- and exogenous[92-97] | |||

| CYP19A1 | rs11575899 | 15:51227749 | 3 | Intron | X | X | X | Metabolism of endo- and exogenous[92-97] | |

| HLAG | rs371194629 | 6:29830804 | 14 | 3'-UTR | X | X | Immune surveillance[98-102] | ||

| IL1A | rs3783553 | 2:112774138 | 4 | 3'-UTR | X | X | Induce chronic inflammation and proliferation[103,104] | ||

| IL4 | rs79071878 | 5:132680584 | 70 | Intron | X | X | X | Immune surveillance and proliferation[40,39,43,105,106] | |

| MDM2 | rs3730485 | 12:68807065 | 40 | Promoter | X | Proliferation and apoptosis[107,108] | |||

| NFKB1 | rs28362491 | 4:102500998 | 4 | Promoter | X | Differentiation, proliferation and apoptosis [109,110] | |||

| TP53 | rs17878362 | 17:7676372 | 16 | Intron | X | X | X | Proliferation, apoptosis, repair, differentiation[111-114] | |

| TP53 | rs17880560 | 17:7668169 | 6 | 3'-Flanking | X | X | Proliferation, apoptosis, repair, differentiation[111-114] | ||

| TYMS | rs151264360 | 18:673444 | 6 | 3'-UTR | X | X | Differentiation, replication and repair[50,105] | ||

| UCP2 | - | - | 45 | 3'-UTR | X | X | Tumor aggressiveness and metastasis[56] | ||

| UGT1A1 | rs8175347 | 2:233760235 | 2 | 3'-UTR | X | X | Metabolism of endo- and exogenous[92-97] | ||

| XRCC1 | rs3213239 | 19:43576907 | 4 | 5'- Flanking | X | Repair[115-117] | |||

According to the single nucleotide polymorphism database (dbSNP); UTR: Untranslated region; INDEL: Insertion-deletions.

Genotyping of polymorphism

Multiplex PCR was used to simultaneously amplify the 16 investigated markers, as shown in Supplementary Table 1. The amplification was performed on ABI Verity thermocycler (Life Technologies, Foster City, CA, United States). A single multiplex reaction used Master Mix QIAGEN Multiplex PCR kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The samples were incubated at 95 °C for 15 min, followed by 35 cycles at 94 °C for 45 s, 60 °C for 90 s, and 72 °C for 1 min, with a final extension at 70 °C for 30 min.

For fragment analysis, we used capillary electrophoresis on the ABI 3130 Genetic Analyzer instrument (Life Technologies). 1.0 μL of PCR product was added to 8.5 μL of HI-DI deionized formamide (Life Technologies) and 0.5 μL of GeneScan 500 LIZ pattern size standard (Life Technologies). After data collection, samples were analyzed on the GeneMapper ID v.3.7 software (Life Technologies).

Analysis of genetic ancestry

Genomic ancestry analysis was performed based on the method described by Santos et al[25] using 62 autosomal ancestry informative markers (AIMs). Two multiplex PCR reactions of 20 and 22 markers were performed and amplicons were analyzed by electrophoresis using the ABI Prism 3130 sequencer and GeneMapper ID v.3.2 software. The individual proportions of European, African, and Amerindian genetic ancestries were estimated using STRUCTURE v.2.3.3 software, assuming three parental populations (European, African, and Amerindian).

Statistical analysis

The categorical variables case and control participants were tested by the Chi-squared test. For ancestry index and age at diagnosis variables we used the Mann-Whitney test. Logistic regression analyses between the genotype model and CRC risk were performed by the SNPassoc package v.1.9-2, along with clinical features variables. The association between genotype and free-relapse survival time was evaluated by Kaplan-Meier plots, performed by the survival package v.2.41-3. Log-rank and Wilcoxon tests were used to examine the genetic effect on survival outcomes. The statistical power was estimated by 10000 simulations. All statistical analyses and plotting were performed with R package v.3.1.2[26]. Differences between groups were considered significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics

We analyzed 140 subjects with CRC and 140 cancer-free individuals. The demographic characteristics of participants were summarized in Table 2, which shows demographic features of the groups. Regarding genomic ancestry, significance was observed with the distribution of African ancestry (P = 0.049), Table 3. However, there was no difference between groups when an analysis of multinomial logistic regression was performed.

Table 2.

Participant demographic and clinical characteristics and their stratification by case and control groups

| Characteristic | Total, n = 280 | Cases, n = 140 | Controls, n = 140 | P value |

| Age (yr) | 48 (21-93) | 59 (23-93) | 37 (21-81) | < 0.001 |

| < 45 | 136 (48.7) | 23 (16.5) | 113 (80.7) | |

| ≥ 45 | 144 (51.3) | 116 (83.5) | 27 (19.3) | |

| Gender | < 0.001 | |||

| Male | 172 (61.6) | 62 (44.6) | 110 (78.6) | |

| Female | 108 (38.4) | 78 (55.4) | 30 (21.4) | |

| Alcohol consumption | < 0.001 | |||

| No | 180 (65.1) | 118 (85.5) | 62 (44.9) | |

| Yes | 96 (34.9) | 20 (14.5) | 76 (55.1) | |

| Eventually | 56 (20.4) | 11 (8.0) | 45 (32.6) | |

| Frequently | 40 (14.5) | 9 (6.5) | 31 (22.5) | |

| Tobacco consumption | < 0.001 | |||

| Never | 182 (65.4) | 68 (48.9) | 114 (82.0) | |

| Already | 96 (24.6) | 71 (48.1) | 25 (18.0) | |

| Former | 66 (23.8) | 55 (39.6) | 11 (7.9) | |

| Current | 30 (10.8) | 16 (11.5) | 14 (10.1) |

Categorized data are presented by absolute numbers of individuals (percentage) and analyzed by Chi-square test. Continuous data are presented by mean (min-max) and analyzed by Mann-Whitney test.

Table 3.

Genetic ancestry distribution between case and control groups

| Genetic ancestry (%) | Total, n = 280 | Cases, n = 140 | Controls, n = 140 | OR (95%CI) | P value |

| European | 65.3 ± 15.5 | 64.2 ± 15.6 | 66.4 ± 15.3 | 0.243 | |

| 95-80 | 50 (17.9) | 21 (15.1) | 29 (20.7) | 1.0 (Reference) | |

| 80-70 | 70 (25.1) | 33 (23.7) | 37 (26.4) | 1.23 (0.59-2.56) | 0.577 |

| 70-60 | 67 (24.0) | 38 (27.3) | 29 (20.7) | 1.81 (0.86-3.80) | 0.117 |

| 60-50 | 47 (16.8) | 22 (15.8) | 25 (17.9) | 1.21 (0.54-2.71) | 0.634 |

| 50-40 | 26 (9.3) | 14 (10.1) | 12 (8.6) | 1.61 (0.62-4.18) | 0.327 |

| 40-30 | 11 (3.9) | 6 (4.3) | 5 (3.6) | 1.66 (0.45-6.16) | 0.451 |

| 30-20 | 7 (2.5) | 5 (3.6) | 2 (1.4) | 3.45 (0.61-19.54) | 0.161 |

| 20-10 | 1 (0.4) | - | 1 (0.7) | - | |

| Amerindian | 16.2 ± 10.1 | 16.0 ± 10.3 | 16.3 ± 9.9 | 0.645 | |

| 02-10 | 90 (32.3) | 45 (32.4) | 45 (32.1) | 1.0 (Reference) | |

| 10-20 | 113 (40.5) | 60 (43.2) | 53 (37.9) | 1.13 (0.65-1.97) | 0.661 |

| 20-30 | 47 (16.8) | 18 (12.9) | 29 (20.7) | 0.62 (0.30-1.27) | 0.193 |

| 30-40 | 21 (7.5) | 11 (7.9) | 10 (7.1) | 1.10 (0.42-2.85) | 0.844 |

| 40-50 | 7 (2.5) | 4 (2.9) | 2 (2.1) | 2.00 (0.35-11.47) | 0.437 |

| 50-60 | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.7) | - | - | |

| African | 18.6 ± 12.0 | 19.8 ± 12.3 | 17.3 ± 11.7 | 0.049 | |

| 02-10 | 81 (29.0) | 36 (25.9) | 45 (32.1) | 1.0 (Reference) | |

| 10-20 | 89 (31.9) | 41 (29.5) | 48 (34.3) | 1.07 (0.58-1.95) | 0.832 |

| 20-30 | 66 (23.7) | 38 (27.3) | 28 (20.0) | 1.70 (0.88-3.27) | 0.114 |

| 30-40 | 28 (10.0) | 15 (10.8) | 13 (9.3) | 1.44 (0.61-3.42) | 0.405 |

| 40-50 | 8 (2.9) | 5 (3.6) | 3 (2.1) | 2.08 (0.47-9.31) | 0.337 |

| 50-60 | 5 (1.8) | 3 (2.2) | 2 (1.4) | 1.87 (0.30-11.83) | 0.504 |

| 60-70 | 2 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | 1.25 (0.07-20.68) | 0.876 |

Categorized data are presented by absolute numbers of individuals (percentage) and analyzed by Chi-square test. Continuous data are presented by mean ± standard variation and analyzed by Mann-Whitney test.

Distribution of genotypes associated with susceptibility to CRC

All INDEL polymorphisms are in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (P > 0.05). The genotypic and allelic frequencies of the subjects are presented in the Table 4. Genotypic frequency (P = 0.01) of IL4 gene polymorphism was significantly different between case-controls, and higher frequency of Del allele were observed in cases than in controls.

Table 4.

Genotype and allele frequency in percentage of patients with colorectal cancer and controls

| Gene | dbSNP |

Case/control (n = 140/140) |

||||||

|

Genotype frequency |

Allele frequency |

HWE |

||||||

| II | ID | DD | P value | I | D | P value | ||

| ACE | rs4646994 | 21.0/14.3 | 49.3/54.3 | 29.7/31.4 | 0.335 | 45.7/41.4 | 54.3/58.6 | 0.161 |

| CASP8 | rs3834129 | 34.5/30.0 | 46.0/46.4 | 19.4/23.6 | 0.605 | 57.6/53.2 | 42.4/46.8 | 0.424 |

| SGSM3 | rs56228771 | 7.2/3.6 | 30.2/36.4 | 62.6/60.0 | 0.274 | 22.3/21.8 | 77.7/78.2 | 0.415 |

| CYP19A1 | rs11575899 | 35.8/37.9 | 49.6/50.0 | 14.6/12.1 | 0.82 | 60.3/62.9 | 39.7/37.1 | 0.402 |

| CYP2E1 | - | 0.7/0.7 | 17.3/12.9 | 82.0/86.4 | 0.588 | 9.4/7.1 | 90.6/92.6 | 0.716 |

| HLAG | rs371194629 | 14.7/13.6 | 43.4/50.0 | 41.9/36.4 | 0.538 | 36.4/38.6 | 63.6/61.4 | 0.514 |

| IL1A | rs3783553 | 46.0/52.1 | 38.8/37.9 | 15.1/10.0 | 0.368 | 65.5/71.1 | 34.5/28.9 | 0.348 |

| IL4 | rs79071878 | 48.9/60.0 | 40.3/37.1 | 10.8/2.9 | 0.017 | 69.1/78.6 | 30.9/21.4 | 0.223 |

| MDM2 | rs3730485 | 50.4/50.7 | 43.2/37.1 | 6.5/12.1 | 0.219 | 71.9/69.3 | 28.1/30.7 | 0.132 |

| NFKB1 | rs28362491 | 38.1/40.7 | 46.0/42.1 | 15.8/17.1 | 0.806 | 61.2/61.8 | 38.8/38.2 | 0.203 |

| TP53 | rs17878362 | 3.6/1.4 | 27.3/32.1 | 69.1/66.4 | 0.383 | 17.3/17.5 | 82.7/82.5 | 0.181 |

| TP53 | rs17880560 | 7.2/7.1 | 39.6/32.9 | 53.2/60.0 | 0.489 | 27.0/23.6 | 73.0/76.4 | 0.297 |

| TYMS | rs151264360 | 46.0/42.9 | 43.9/42.1 | 10.1/15.0 | 0.459 | 68.0/63.9 | 32.0/36.1 | 0.308 |

| UCP2 | - | 6.6/9.3 | 35.3/44.3 | 58.1/46.4 | 0.149 | 24.3/31.4 | 75.7/68.6 | 0.745 |

| UGT1A1 | rs8175347 | 11.5/10.8 | 44.6/46.0 | 43.9/43.2 | 0.785 | 33.8/33.8 | 66.2/66.2 | 0.735 |

| XRCC1 | rs3213239 | 41.7/42.9 | 47.5/45.0 | 10.8/12.1 | 0.894 | 65.5/65.4 | 34.5/34.6 | 0.941 |

Genotype frequencies are presented as the percentage of patients with colorectal cancer/percentage of controls, and analysis by Chi-square test. dbSNP: Register of genetic variation on NCBI database; bp: Base pairs of DNA sequence; HWE: Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium.

The significant logistic regression analyses between case-controls are summarized in Table 5. Del allele polymorphism in IL4 gene (P = 0.0110) was associated with an increased risk of CRC development, while Ins allele in UCP2 (P = 0.0210) was decreased CRC risk. Furthermore, the Del allele in the TYMS (P = 0.0120) gene was associated with decreased CRC risk.

Table 5.

The logistic regression analyses between case-control and insertion-deletions polymorphism

| Gene | Model | OR (95%CI) | P-value |

| IL4 | Ins/Ins vs Del/Ins + Del/Del | 2.26 (1.20-4.31) | 0.0110 |

| TYMS | Ins/Ins + Del/Ins vs Del/Del | 0.26 (0.08-0.75) | 0.0120 |

| UCP2 | Del/Del vs Del/Ins + Ins/Ins | 0.48 (0.25-0.90) | 0.0210 |

Adjusted by age at diagnosis, gender, alcohol consumption, tobacco consumption and ancestry distribution. The Supplementary Table 2 shows the genotype frequency and all logistic regression.

Distribution of genotypes associated with prognostic follow-up in CRC

The baseline characteristics of CRC patients are summarized in Table 6. The follow-up time median was 5.28 years among 78 patients who had complete genotype and follow-up information. The 5-year free-relapse rate was 70% and the 10-year free-relapse rate was 66.4%. The 5-year survival rate was 91.4% and the 10-year survival rate was 87.9%.

Table 6.

Clinical characteristics of patients with colorectal cancer at diagnosis and follow-up

| Characteristics | Cases (n = 140) |

| Tumor localization | |

| Colon | 25 (17.9) |

| Rectosigmoid | 115 (82.1) |

| Tumor grade | |

| G1, G2 | 130 (92.9) |

| G3, G4 | 10 (7.1) |

| Depth of invasion | |

| T1, T2 | 37 (26.6) |

| T3, T4 | 89 (64.0) |

| Tx | 13 (9.4) |

| Lymph node involvement | |

| N0 | 77 (55.4) |

| N1, N2 | 47 (33.8) |

| Nx | 15 (10.8) |

| Distant metastasis | |

| M0 | 109 (78.4) |

| M1 | 13 (9.4) |

| Mx | 17 (12.2) |

| AJCC stage | |

| StageI | 31 (22.3) |

| Stage II | 43 (30.9) |

| Stage III | 43 (30.9) |

| Stage IV | 15 (10.8) |

| Unknown | 7 (5.1) |

| Relapse, Yes | 48 (34.5) |

| Death, Yes | 18 (12.9) |

Categorized data are presented by absolute numbers (percentage) and continuous data are presented as median (min-max). Tumors were classified according to the guidelines of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system.

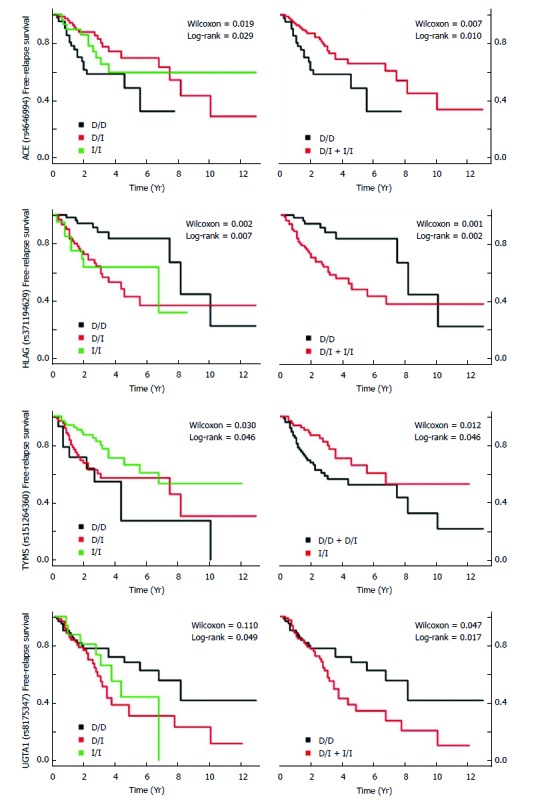

We also evaluated the genetic impact in the clinical features. The Del allele in NFKB1 and CASP8 were associated with more incidents to colon than rectosigmoid (Table 7). In relation to the INDEL association with TNM stage risk, the Ins alleles of ACE, HLAG and TP53 (6 bp INDEL) were associated with a higher TNM stage (Table 8). Regarding the INDEL association with relapse risk, the Ins alleles of ACE, HLAG, and UGT1A1 were associated with relapse risk, as well as the Del allele of TYMS (Table 9). Moreover, these findings corroborate those observed in the free-relapse survival curve (Figure 1). Regarding INDEL association with death risk, the Ins alleles of SGSM3 and UGT1A1 were associated with death risk (Table 10).

Table 7.

The significant insertion-deletions associations with anatomic localization

| Gene | Model | OR (95%CI) | P value |

| CASP8 | Ins/Ins vs Del/Ins + Del/Del | 0.28 (0.08-0.97) | 0.0303 |

| NFKB1 | Ins/Ins vs Del/Ins+Del/Del | 0.31 (0.10-0.93) | 0.0276 |

Logistic regression adjusted for confounders. The Supplementary Table 3 shows the genotype frequency and all logistic regression.

Table 8.

The significant insertion-deletions associations with tumor node metastasis stage risks

| Gene | Model | OR (95%CI) | P value |

| ACE | Del/Del vs Del/Ins + Ins/Ins | 2.82 (1.26-6.31) | 0.0092 |

| HLAG | Del/Del + Del/Ins vs Ins/Ins | 2.74 (1.01-7.42) | 0.0416 |

| TP53 06 bp | Del/Del vs Del/Ins + Ins/Ins | 2.50 (1.23-5.06) | 0.0099 |

Logistic regression adjusted for confounders. The Supplementary Table 3 shows the genotype frequency and all logistic regression.

Table 9.

The significant insertion-deletions associations with relapse risks

| Gene | Model | Time of follow-up | OR (95%CI) | P value |

| ACE | Del/Del vs Del/Ins + Ins/Ins | 2 yr | 0.32 (0.13-0.77) | 0.0113 |

| ACE | Del/Del vs Del/Ins + Ins/Ins | 3 yr | 0.37 (0.15-0.91) | 0.0298 |

| HLAG | Del/Del vs Del/Ins + Ins/Ins | 2 yr | 2.75 (1.07-7.08) | 0.0281 |

| HLAG | Del/Del vs Del/Ins + Ins/Ins | 4 yr | 2.83 (1.07-7.52) | 0.0332 |

| HLAG | Del/Del vs Del/Ins + Ins/Ins | 5 yr | 3.47 (1.20-9.99) | 0.0194 |

| TYMS | Ins/Ins vs Del/Ins + Del/Del | 2 yr | 3.35 (1.36-8.28) | 0.0058 |

| TYMS | Ins/Ins vs Del/Ins + Del/Del | 3 yr | 3.42 (1.41-8.28) | 0.0046 |

| UGT1A1 | Del/Del vs Del/Ins + Ins/Ins | 4 yr | 3.23 (1.27-8.22) | 0.0116 |

| UGT1A1 | Del/Del vs Del/Ins + Ins/Ins | 5 yr | 3.50 (1.24-9.84) | 0.0145 |

Logistic regression adjusted for confounders. The Supplementary Table 4 shows the genotype frequency of all insertion-deletions polymorphism.

Figure 1.

Free-relapse survival of patients with colorectal cancer related with significant insertion-deletions. Logistic regression adjusted for confounders. The analyses and graphic were performed by survival packages, in R statistical software.

Table 10.

The significant insertion-deletions associations with death risks

| Gene | Model | Time of follow-up | OR (95%CI) | P value |

| SGSM3 | Del/Del vs Del/Ins + Ins/Ins | 6 yr | 3.61 (1.01-12.92) | 0.0487 |

| SGSM3 | Del/Del vs Del/Ins + Ins/Ins | 7 yr | 4.60 (1.16-18.23) | 0.0260 |

| UGT1A1 | Del/Del vs Del/Ins + Ins/Ins | 6 yr | 5.30 (1.43-19.73) | 0.0084 |

| UGT1A1 | Del/Del vs Del/Ins + Ins/Ins | 7 yr | 4.64 (1.19-18.10) | 0.0202 |

| UGT1A1 | Del/Del vs Del/Ins + Ins/Ins | 8 yr | 6.50 (1.47-28.80) | 0.0091 |

Logistic regression adjusted for confounders. The Supplementary Table 5 shows the genotype frequency of all insertion-deletions polymorphism.

DISCUSSION

Despite the effective strategies for prevention, early detection, and treatment[27-32], there are ethnic differences in the CRC incidence and survival[33,34], specifically in individuals with African American ancestry, who have higher CRC incidence and lower 5-years survival rates than other ethnic groups[33-38].

In this work, we evaluated the association between 16 INDEL [ACE, CASP8, SGSM3, CYP19A1, CYP2E1, HLAG, IL1A, MDM2, NFKB1, TP53 (16 and 6 bp), TYMS, UCP2, XRCC1, IL4 and UGT1A1] and the risk of developing CRC in a Brazilian population, as well as their clinical features. We found significant association between three investigated INDEL polymorphisms and CRC risk, two associated with anatomical localization, three associated with TNM stage, four associated with early relapse risk, and two associated with death risk before 10 years.

Variations in the IL-4 activity or in the IL-4 receptor due to mutations have been associated with cell proliferation and might affect signal transduction pathways in cancer[39]. We evaluated INDEL of 70 bp in intron 3 of the IL4 gene (rs79071878), a variation which may influence the production of this cytokine. The higher IL-4 production may result in diminished cell-mediated immune response, and escape from immune surveillance in the tumor cells. The cell-mediated immune response may be inhibited by downregulating the expression of Th1 cytokines, decreasing the CD8+ T-cell response in the tumor microenvironment[39-41]. Furthermore, this INDEL has been associated with gastric cancer[39] and other immune diseases[42,43]. However, this is the first study indicating an association between this IL4 polymorphism and the risk of developing CRC. Our results indicate that the Del allele in IL4 was associated with the risk of developing CRC.

The TYMS gene plays an essential role in the biosynthesis of the DNA-component thymidylate (dTTP) and is required for DNA replication and repair[44]. The insertion of 6 bp in the 3’-UTR of TYMS primary transcript (rs151264360) may significantly influence gene expression as shown by using a luciferase assay[15]. Mandola et al[15] observed that a Del allele might decrease the TYMS mRNA stability, and the TYMS protein expression. Moreover, Rahman et al[45] showed in vitro that TYMS overexpression might induce the transformation of mammalian cells into a malignant phenotype. Studies indicate that this INDEL is associated with many cancers[46-49], especially colorectal[48]. These results suggested that this INDEL variation might decrease CRC risk, as showed in the present work. However, this finding diverges from data from Mexico[50], in which association was not observed. On the other hand, our results showed that this Del allele was associated with an increase relapse risk.

Uncoupling proteins (UCPs) are a family of mitochondrial proteins, which were originally reported to play essential roles in reducing the reactive oxygen species[51,52]. UCP2 plays a role in carcinogenesis in various tissues, including colon cancer, and regulates the responsiveness of carcinomas to chemotherapy[53-56]. Adaptive mechanisms of cancer cells include resistance to tumor growth inhibition and evasion of apoptosis, and cellular events that are appreciably affected by oxidative stress[57,58]. The UCP2 expression level is significantly higher in colon cancer tissue than in its adjacent tissue and UCP2 may play a role in intestinal epithelial cells from benign to malignant transformation[59]. However, the role of UCP2 in development of colon cancer is unclear. INDEL polymorphism may regulate UCP2 mRNA stability via post-transcriptional modification of UCP2 protein expression[60,61]. Indeed, in the present study was observed that INDEL polymorphism might be associated with colorectal cancer. However, this is the first study indicating an association between this UCP2 polymorphism and the risk of developing CRC.

The renin-angiotensin system (RAS), which regulates systemic blood pressure, also exerts local effects on cell proliferation, apoptosis, inflammation and angiogenesis in different tissues[62]. In addition, there is evidence linking the RAS with tumorigenesis and tumor angiogenesis[63]. The polymorphisms in the various components of the RAS that may possess clinical relevance[62], and the most common polymorphism in the gene encoding angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) is INDEL of a 287-bp fragment in intron 16 and is responsible for the inter-individual variation in the ACE levels in blood and tissues[64]. The insertion allele in this gene was associated with ACE levels, the rate of disease progression, shorter TTF, and lower circulating levels of ACE[62,65]. This INDEL has been associated with cancer risk susceptibility[66-68], including CRC[65,68], and with response to bevacizumab[62]. Our results indicate that Ins allele was not associated with CRC risk development, as showed by Yang et al’s meta-analysis[69] and Liu et al[70] case-control study (241 cases and 299 control, China). On the other hand, our results also showed that this INDEL was also associated with TNM stage risk and relapse risk.

The HLAG is an important immunomodulatory molecule related to several mechanisms of tolerance[71]. Since the discovery of the HLA-G protein expression in cancer[72], several pieces of evidence have supported a considerable role for HLA-G in tumor cell escape from immuno-surveillance and antitumor immune responses[73]. The 14 bp INDEL (rs371194629) has been suggested to have functional significance. The Ins allele has been shown to be associated with alternative splicing, resulting in deletion of 92 bp in exon 5 from mature mRNA, which then leads to low levels of soluble HLA-G (sHLA-G)[74]. Furthermore, our results indicated that the Ins allele was associated with a higher TNM stage and relapse up to 5 years. These findings suggest that low levels of sHLA-G might influence in poor prognostics.

UGT1 is a family of membrane-bound enzymes involved in the inactivation and elimination of lipophilic molecules through glucorination. Moreover, variants in this gene have been shown to be useful tools to identifying patients more likely to experience severe toxicity related to irinotecan-containg regimens[75]. In particular, INDEL variants in UGT1A1 (rs8175347) were associated with significantly decreased glucuronidation activity, which results in reduced SN-38 clearance[76] and an increased risk of these toxicities in patients homozygous for the Ins allele[75,77-80]. Our results showed that the Ins allele in UGT1A1 was associated with early relapse risk, as well as with death risk prior to 8 years. This genetic variation may identify patients who might benefit from increased irinotecan dosing, as observed by Chen et al[75].

The SGSM3 belongs to a novel protein family consisting of three members and appears to be associated with small G-protein coupled receptor signal transduction pathways, and could control cellular functions by a Ras-mediated signaling pathway[81]. Studies have linked Rab dysfunction to various human diseases including cancer[82,83], and our results have shown that the Ins allele might also be associated with death risk prior to 8 years.

The aims of this study were to determine the association between CRC risk and the clinical features with 16 INDEL in genes involved with carcinogenesis pathways in an admixed population from Brazil. Although we have achieved our goal, there are limitations regarding sample number. We suggest, therefore, that an extensive study should be conducted in the Brazilian population to confirm the findings, as well as in other admixed populations.

In summary, the present work indicates that polymorphisms in ACE (rs4646994), TYMS (rs151264360), UCP2 (45 bp), IL4 (rs79071878), NFKB1 (rs28362491), CASP8 (rs3834129), TP53 (rs17880560), HLAG (rs371194629), UGT1A1 (rs3213239), and SGSM3 (rs56228771) genes were associated with CRC risk and clinical features in an admixed population. These data suggest that this cancer panel might be useful as a complementary tool for better clinical management, and more studies need to be conducted to confirm these findings.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all participants who allowed us to carry out this study. We are also grateful to the students and technicians from LGHM/UFPA/PA, LBBM-LABMULT/UFRN/RN, Laboratory of Pathology and Cytopathology/Liga Norte Riograndense Contra o Câncer/RN and Hemovida/RN. We are also grateful to Philip Barsanti for the invaluable and constructive English review of the manuscript. Furthermore, we are grateful to André Ribeiro-dos-Santos and Ana Paula Schaan for help with statistical revision.

COMMENTS

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer type in men and the second in women. Despite the effective strategies for prevention, early detection, and treatment, there are ethnic differences in CRC incidence and survival. These variances occur specifically in African Americans, who have higher CRC incidence and lower survival rates than other ethnic groups. Thus, the present study evaluated the association between 16 insertion-deletions (INDEL) polymorphisms with colorectal cancer risk in an admixture population, as well with clinical features.

Research frontiers

The second most abundant form of genetic variation in humans, after single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), are the INDEL. The INDEL understanding is important because they are common genetic variations within genomes, and they may alter human traits and cause diseases, including colorectal cancer, by modifying the coding region or mRNA stability. One of the challenges for genetic polymorphism association studies is the lack of knowledge regarding the frequency of the polymorphism in the targeted population, mainly in admixed populations (e.g. Brazil).

Innovations and breakthroughs

This is the first case-control study to evaluate the association between these 16 INDEL polymorphisms with colorectal risk, clinical features and prognostic follow-up in an admixture population, adopting the methodology that can be easily used to perform multiplexing assays.

Applications

This pilot study is design and findings could be used to determine sample size for a larger randomized controlled study aiming to test the impact of these INDEL polymorphism panel in colorectal risk, clinical features and prognostic follow-up.

Terminology

Ancestry informative marker - In population genetics, an ancestry informative marker (AIM) is a polymorphism that exhibits substantially different frequencies between populations from different geographical regions. A set of many AIMs can be used to estimate the proportion of ancestry of an individual derived from each geographical region.

Peer-review

This is an interesting study aiming to determine the association between CRC risk, and the clinical features with 16 INDEL in genes involved with carcinogenesis pathways in an admixed population from Brazil. The overall structure of the manuscript is complete and conforms to the academic rules.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Country of origin: Brazil

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Supported by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), No. 483031/2013-5; Rede de Pesquisa em Genomica Populacional Humana, No. Biocomputacional/CAPES-051/2013; Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Pará, No. 155/2014; and Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio Grande do Norte, No. 005/2011.

Institutional review board statement: This study was reviewed and approved by the Liga Norte Riograndense Contra o Câncer Institutional Review Board.

Informed consent statement: All study participants, or their legal guardian, provided informed written consent prior to study enrollment.

Conflict-of-interest statement: No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

Data sharing statement: Technical appendix, statistical code, and dataset are available from the corresponding author at viviansilbiger@hotmail.com; viviansilbiger@ufrnet.br.

Peer-review started: April 27, 2017

First decision: June 5, 2017

Article in press: August 15, 2017

P- Reviewer: Dai ZJ, Engin AB, Wang YH S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Huang Y

Contributor Information

Diego Marques, Laboratório de Bioanálise e Biotecnologia Molecular, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal 59012-570, Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil; Programa de Pós-graduação em Ciências Farmacêutica, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal 59012-570, Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil; Laboratório de Genética Humana e Médica, Universidade Federal do Pará, Belém 66055-080, Pará, Brazil.

Layse Raynara Ferreira-Costa, Laboratório de Bioanálise e Biotecnologia Molecular, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal 59012-570, Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil.

Lorenna Larissa Ferreira-Costa, Laboratório de Bioanálise e Biotecnologia Molecular, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal 59012-570, Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil.

Romualdo da Silva Correa, Departamento de Cirurgia Oncológica, Liga Norte Riograndense Contra o Câncer, Natal 59040-000, Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil.

Aline Maciel Pinheiro Borges, Departamento de Cirurgia Oncológica, Liga Norte Riograndense Contra o Câncer, Natal 59040-000, Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil.

Fernanda Ribeiro Ito, Departamento de Cirurgia Oncológica, Liga Norte Riograndense Contra o Câncer, Natal 59040-000, Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil.

Carlos Cesar de Oliveira Ramos, Laboratório de Patologia e Citopatologia, Liga Norte Riograndense Contra o Câncer, Natal 59040-000, Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil.

Raul Hernandes Bortolin, Laboratório de Bioanálise e Biotecnologia Molecular, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal 59012-570, Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil; Programa de Pós-graduação em Ciências Farmacêutica, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal 59012-570, Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil.

André Ducati Luchessi, Laboratório de Bioanálise e Biotecnologia Molecular, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal 59012-570, Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil; Departamento de Análises Clínicas e Toxicológicas, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal 59012-570, Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil; Programa de Pós-graduação em Ciências Farmacêutica, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal 59012-570, Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil.

Ândrea Ribeiro-dos-Santos, Laboratório de Genética Humana e Médica, Universidade Federal do Pará, Belém 66055-080, Pará, Brazil; Núcleo de Pesquisas em Oncologia, Universidade Federal do Pará, Belém 66073-005, Pará, Brazil.

Sidney Santos, Laboratório de Genética Humana e Médica, Universidade Federal do Pará, Belém 66055-080, Pará, Brazil; Núcleo de Pesquisas em Oncologia, Universidade Federal do Pará, Belém 66073-005, Pará, Brazil.

Vivian Nogueira Silbiger, Laboratório de Bioanálise e Biotecnologia Molecular, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal 59012-570, Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil; Departamento de Análises Clínicas e Toxicológicas, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal 59012-570, Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil; Programa de Pós-graduação em Ciências Farmacêutica, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal 59012-570, Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil. viviansilbiger@ufrnet.br.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F. GLOBOCCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11 [Internet]. Lyon, France: International Angency for Research on Cancer; 2013. Accessed on 2016-2-12. Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr/

- 2.Hong Y, Wu G, Li W, Liu D, He K. A comprehensive meta-analysis of genetic associations between five key SNPs and colorectal cancer risk. Oncotarget. 2016;7:73945–73959. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zaridze DG. Molecular epidemiology of cancer. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2008;73:532–542. doi: 10.1134/s0006297908050064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu J, He C, Xu Q, Xing C, Yuan Y. NOD2 polymorphisms associated with cancer risk: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e89340. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gomez SL, Shariff-Marco S, DeRouen M, Keegan TH, Yen IH, Mujahid M, Satariano WA, Glaser SL. The impact of neighborhood social and built environment factors across the cancer continuum: Current research, methodological considerations, and future directions. Cancer. 2015;121:2314–2330. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peters U, Bien S, Zubair N. Genetic architecture of colorectal cancer. Gut. 2015;64:1623–1636. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lichtenstein P, Holm NV, Verkasalo PK, Iliadou A, Kaprio J, Koskenvuo M, Pukkala E, Skytthe A, Hemminki K. Environmental and heritable factors in the causation of cancer--analyses of cohorts of twins from Sweden, Denmark, and Finland. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:78–85. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007133430201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Czene K, Lichtenstein P, Hemminki K. Environmental and heritable causes of cancer among 9.6 million individuals in the Swedish Family-Cancer Database. Int J Cancer. 2002;99:260–266. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iengar P. An analysis of substitution, deletion and insertion mutations in cancer genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:6401–6413. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mullaney JM, Mills RE, Pittard WS, Devine SE. Small insertions and deletions (INDELs) in human genomes. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:R131–R136. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mills RE, Pittard WS, Mullaney JM, Farooq U, Creasy TH, Mahurkar AA, Kemeza DM, Strassler DS, Ponting CP, Webber C, et al. Natural genetic variation caused by small insertions and deletions in the human genome. Genome Res. 2011;21:830–839. doi: 10.1101/gr.115907.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boschiero C, Gheyas AA, Ralph HK, Eory L, Paton B, Kuo R, Fulton J, Preisinger R, Kaiser P, Burt DW. Detection and characterization of small insertion and deletion genetic variants in modern layer chicken genomes. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:562. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1711-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Veerappa AM, Vishweswaraiah S, Lingaiah K, Murthy NM, Suresh RV, Belur K, Ramachandra NB, Tejaswini, Patel NB, Gowda PK. Insertion-deletions burden in copy number polymorphisms of the Tibetan population. Indian J Hum Genet. 2014;20:166–174. doi: 10.4103/0971-6866.142888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao X, Zhang S, Zhu Z. Genetic variation of ErbB4 confers risk of colorectal cancer in a Chinese Han population. Cancer Biomark. 2014;14:435–439. doi: 10.3233/CBM-140420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mandola MV, Stoehlmacher J, Zhang W, Groshen S, Yu MC, Iqbal S, Lenz HJ, Ladner RD. A 6 bp polymorphism in the thymidylate synthase gene causes message instability and is associated with decreased intratumoral TS mRNA levels. Pharmacogenetics. 2004;14:319–327. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200405000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu Z, Li X, Qu X, He Y, Ring BZ, Song E, Su L. Intron 3 16 bp duplication polymorphism of TP53 contributes to cancer susceptibility: a meta-analysis. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:643–647. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hernandez-Suarez G, Sanabria MC, Serrano M, Herran OF, Perez J, Plata JL, Zabaleta J, Tenesa A. Genetic ancestry is associated with colorectal adenomas and adenocarcinomas in Latino populations. Eur J Hum Genet. 2014;22:1208–1216. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2013.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carvalho DC, Wanderley AV, Amador MA, Fernandes MR, Cavalcante GC, Pantoja KB, Mello FA, de Assumpção PP, Khayat AS, Ribeiro-Dos-Santos Â, Santos S, Dos Santos NP. Amerindian genetic ancestry and INDEL polymorphisms associated with susceptibility of childhood B-cell Leukemia in an admixed population from the Brazilian Amazon. Leuk Res. 2015;39:1239–1245. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2015.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cassiano GC, Santos EJ, Maia MH, Furini Ada C, Storti-Melo LM, Tomaz FM, Trindade PC, Capobianco MP, Amador MA, Viana GM, et al. Impact of population admixture on the distribution of immune response co-stimulatory genes polymorphisms in a Brazilian population. Hum Immunol. 2015;76:836–842. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2015.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campanella NC, Berardinelli GN, Scapulatempo-Neto C, Viana D, Palmero EI, Pereira R, Reis RM. Optimization of a pentaplex panel for MSI analysis without control DNA in a Brazilian population: correlation with ancestry markers. Eur J Hum Genet. 2014;22:875–880. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2013.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bastos-Rodrigues L, Pimenta JR, Pena SD. The genetic structure of human populations studied through short insertion-deletion polymorphisms. Ann Hum Genet. 2006;70:658–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2006.00287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mills RE, Luttig CT, Larkins CE, Beauchamp A, Tsui C, Pittard WS, Devine SE. An initial map of insertion and deletion (INDEL) variation in the human genome. Genome Res. 2006;16:1182–1190. doi: 10.1101/gr.4565806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ribeiro-Rodrigues EM, dos Santos NP, dos Santos AK, Pereira R, Amorim A, Gusmão L, Zago MA, dos Santos SE. Assessing interethnic admixture using an X-linked insertion-deletion multiplex. Am J Hum Biol. 2009;21:707–709. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weber JL, David D, Heil J, Fan Y, Zhao C, Marth G. Human diallelic insertion/deletion polymorphisms. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:854–862. doi: 10.1086/342727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Santos NP, Ribeiro-Rodrigues EM, Ribeiro-Dos-Santos AK, Pereira R, Gusmão L, Amorim A, Guerreiro JF, Zago MA, Matte C, Hutz MH, et al. Assessing individual interethnic admixture and population substructure using a 48-insertion-deletion (INSEL) ancestry-informative marker (AIM) panel. Hum Mutat. 2010;31:184–190. doi: 10.1002/humu.21159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.R Development Core Team. R A language and environment for statistical computing. R Found Stat Comput, Vienna, Austria. Available from: http://www.r-project.org/

- 27.Schoen RE, Pinsky PF, Weissfeld JL, Yokochi LA, Church T, Laiyemo AO, Bresalier R, Andriole GL, Buys SS, Crawford ED, et al. Colorectal-cancer incidence and mortality with screening flexible sigmoidoscopy. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2345–2357. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1114635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mandel JS, Bond JH, Church TR, Snover DC, Bradley GM, Schuman LM, Ederer F. Reducing mortality from colorectal cancer by screening for fecal occult blood. Minnesota Colon Cancer Control Study. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1365–1371. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199305133281901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nishihara R, Wu K, Lochhead P, Morikawa T, Liao X, Qian ZR, Inamura K, Kim SA, Kuchiba A, Yamauchi M, et al. Long-term colorectal-cancer incidence and mortality after lower endoscopy. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1095–1105. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for colorectal cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:627–637. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-9-200811040-00243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scambler G, Hopkins A. Generating a model of epileptic stigma: the role of qualitative analysis. Soc Sci Med. 1990;30:1187–1194. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(90)90258-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Atkin WS, Edwards R, Kralj-Hans I, Wooldrage K, Hart AR, Northover JM, Parkin DM, Wardle J, Duffy SW, Cuzick J; UK Flexible Sigmoidoscopy Trial Investigators. Once-only flexible sigmoidoscopy screening in prevention of colorectal cancer: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;375:1624–1633. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60551-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Soneji S, Iyer SS, Armstrong K, Asch DA. Racial disparities in stage-specific colorectal cancer mortality: 1960-2005. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:1912–1916. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robbins AS, Siegel RL, Jemal A. Racial disparities in stage-specific colorectal cancer mortality rates from 1985 to 2008. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:401–405. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.5527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu BU, Longstreth GF, Ngor EW. Screening colonoscopy versus sigmoidoscopy: implications of a negative examination for cancer prevention and racial disparities in average-risk patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:852–861.e1-2. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Corley DA, Jensen CD, Marks AR, Zhao WK, de Boer J, Levin TR, Doubeni C, Fireman BH, Quesenberry CP. Variation of adenoma prevalence by age, sex, race, and colon location in a large population: implications for screening and quality programs. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:172–180. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lieberman DA, Holub JL, Moravec MD, Eisen GM, Peters D, Morris CD. Prevalence of colon polyps detected by colonoscopy screening in asymptomatic black and white patients. JAMA. 2008;300:1417–1422. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.12.1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kupfer SS, Anderson JR, Hooker S, Skol A, Kittles RA, Keku TO, Sandler RS, Ellis NA. Genetic heterogeneity in colorectal cancer associations between African and European americans. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1677–1685, 1685.e1-1685.e8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bhayal AC, Krishnaveni D, Rao KP, Kumar AR, Jyothy A, Nallari P, Venkateshwari A. Significant Association of Interleukin4 Intron 3 VNTR Polymorphism with Susceptibility to Gastric Cancer in a South Indian Population from Telangana. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0138442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nakashima H, Miyake K, Inoue Y, Shimizu S, Akahoshi M, Tanaka Y, Otsuka T, Harada M. Association between IL-4 genotype and IL-4 production in the Japanese population. Genes Immun. 2002;3:107–109. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gaur P, Singh AK, Shukla NK, Das SN. Inter-relation of Th1, Th2, Th17 and Treg cytokines in oral cancer patients and their clinical significance. Hum Immunol. 2014;75:330–337. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Anovazzi G, Kim YJ, Viana AC, Curtis KM, Orrico SR, Cirelli JA, Scarel-Caminaga RM. Polymorphisms and haplotypes in the interleukin-4 gene are associated with chronic periodontitis in a Brazilian population. J Periodontol. 2010;81:392–402. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.090392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cabantous S, Poudiougou B, Oumar AA, Traore A, Barry A, Vitte J, Bongrand P, Marquet S, Doumbo O, Dessein AJ. Genetic evidence for the aggravation of Plasmodium falciparum malaria by interleukin 4. J Infect Dis. 2009;200:1530–1539. doi: 10.1086/644600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burdelski C, Strauss C, Tsourlakis MC, Kluth M, Hube-Magg C, Melling N, Lebok P, Minner S, Koop C, Graefen M, et al. Overexpression of thymidylate synthase (TYMS) is associated with aggressive tumor features and early PSA recurrence in prostate cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6:8377–8387. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rahman L, Voeller D, Rahman M, Lipkowitz S, Allegra C, Barrett JC, Kaye FJ, Zajac-Kaye M. Thymidylate synthase as an oncogene: a novel role for an essential DNA synthesis enzyme. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:341–351. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guan X, Liu H, Ju J, Li Y, Li P, Wang LE, Brewster AM, Buchholz TA, Arun BK, Wei Q, et al. Genetic variant rs16430 6bp > 0bp at the microRNA-binding site in TYMS and risk of sporadic breast cancer risk in non-Hispanic white women aged ≤ 55 years. Mol Carcinog. 2015;54:281–290. doi: 10.1002/mc.22097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shen R, Liu H, Wen J, Liu Z, Wang LE, Wang Q, Tan D, Ajani JA, Wei Q. Genetic polymorphisms in the microRNA binding-sites of the thymidylate synthase gene predict risk and survival in gastric cancer. Mol Carcinog. 2015;54:880–888. doi: 10.1002/mc.22160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou JY, Shi R, Yu HL, Zeng Y, Zheng WL, Ma WL. The association between two polymorphisms in the TS gene and risk of cancer: a systematic review and pooled analysis. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:2103–2116. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shaw GM, Yang W, Perloff S, Shaw NM, Carmichael SL, Zhu H, Lammer EJ. Thymidylate synthase polymorphisms and risks of human orofacial clefts. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2013;97:95–100. doi: 10.1002/bdra.23114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gallegos-Arreola MP, Peralta-Leal V, Morgan-Villela G, Puebla-Pérez AM. [Frequency of TS1494del6 polymorphism in colorectal patients from west of Mexico] Rev Invest Clin. 2008;60:21–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang M, Li G, Yang Z, Wang L, Zhang L, Wang T, Zhang Y, Zhang S, Han Y, Jia L. Uncoupling protein 2 downregulation by hypoxia through repression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ promotes chemoresistance of non-small cell lung cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:8083–8094. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Krauss S, Zhang CY, Lowell BB. The mitochondrial uncoupling-protein homologues. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:248–261. doi: 10.1038/nrm1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Baffy G. Uncoupling protein-2 and cancer. Mitochondrion. 2010;10:243–252. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2009.12.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Esteves P, Pecqueur C, Ransy C, Esnous C, Lenoir V, Bouillaud F, Bulteau AL, Lombès A, Prip-Buus C, Ricquier D, et al. Mitochondrial retrograde signaling mediated by UCP2 inhibits cancer cell proliferation and tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2014;74:3971–3982. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-3383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dalla Pozza E, Fiorini C, Dando I, Menegazzi M, Sgarbossa A, Costanzo C, Palmieri M, Donadelli M. Role of mitochondrial uncoupling protein 2 in cancer cell resistance to gemcitabine. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1823:1856–1863. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kuai XY, Ji ZY, Zhang HJ. Mitochondrial uncoupling protein 2 expression in colon cancer and its clinical significance. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:5773–5778. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i45.5773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Benhar M, Engelberg D, Levitzki A. ROS, stress-activated kinases and stress signaling in cancer. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:420–425. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lenaz G. The mitochondrial production of reactive oxygen species: mechanisms and implications in human pathology. IUBMB Life. 2001;52:159–164. doi: 10.1080/15216540152845957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Horimoto M, Resnick MB, Konkin TA, Routhier J, Wands JR, Baffy G. Expression of uncoupling protein-2 in human colon cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:6203–6207. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lentes KU, Tu N, Chen H, Winnikes U, Reinert I, Marmann G, Pirke KM. Genomic organization and mutational analysis of the human UCP2 gene, a prime candidate gene for human obesity. J Recept Signal Transduct Res. 1999;19:229–244. doi: 10.3109/10799899909036648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tu N, Chen H, Winnikes U, Reinert I, Marmann G, Pirke KM, Lentes KU. Structural organization and mutational analysis of the human uncoupling protein-2 (hUCP2) gene. Life Sci. 1999;64:PL41–PL50. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(98)00555-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Moreno-Muñoz D, de la Haba-Rodríguez JR, Conde F, López-Sánchez LM, Valverde A, Hernández V, Martínez A, Villar C, Gómez-España A, Porras I, et al. Genetic variants in the renin-angiotensin system predict response to bevacizumab in cancer patients. Eur J Clin Invest. 2015;45:1325–1332. doi: 10.1111/eci.12557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.George AJ, Thomas WG, Hannan RD. The renin-angiotensin system and cancer: old dog, new tricks. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:745–759. doi: 10.1038/nrc2945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rodríguez-Pérez JC, Rodríguez-Esparragón F, Hernández-Perera O, Anabitarte A, Losada A, Medina A, Hernández E, Fiuza D, Avalos O, Yunis C, et al. Association of angiotensinogen M235T and A(-6)G gene polymorphisms with coronary heart disease with independence of essential hypertension: the PROCAGENE study. Prospective Cardiac Gene. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:1536–1542. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01186-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.van der Knaap R, Siemes C, Coebergh JW, van Duijn CM, Hofman A, Stricker BH. Renin-angiotensin system inhibitors, angiotensin I-converting enzyme gene insertion/deletion polymorphism, and cancer: the Rotterdam Study. Cancer. 2008;112:748–757. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Srivastava K, Srivastava A, Mittal B. Angiotensin I-converting enzyme insertion/deletion polymorphism and increased risk of gall bladder cancer in women. DNA Cell Biol. 2010;29:417–422. doi: 10.1089/dna.2010.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.de Martino M, Klatte T, Schatzl G, Waldert M, Remzi M, Haitel A, Kramer G, Marberger M. Insertion/deletion polymorphism of angiotensin I-converting enzyme gene is linked with chromophobe renal cell carcinoma. Urology. 2011;77:1005.e9–1005.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Xie Y, You C, Chen J. An updated meta-analysis on association between angiotensin I-converting enzyme gene insertion/deletion polymorphism and cancer risk. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:6567–6579. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-1842-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yang H, Cai C, Ye L, Rao Y, Wang Q, Hu D, Huang X. The relationship between angiotensin-converting enzyme gene insertion/deletion polymorphism and digestive cancer risk: Insights from a meta-analysis. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2015;16:1306–1313. doi: 10.1177/1470320315585908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liu SY, Sima X, Wang CH, Gao M. The association between ACE polymorphism and risk of colorectal cancer in a Chinese population. Clin Biochem. 2011;44:1223–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2011.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zambra FM, Biolchi V, de Cerqueira CC, Brum IS, Castelli EC, Chies JA. Immunogenetics of prostate cancer and benign hyperplasia--the potential use of an HLA-G variant as a tag SNP for prostate cancer risk. HLA. 2016;87:79–88. doi: 10.1111/tan.12741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Paul P, Rouas-Freiss N, Khalil-Daher I, Moreau P, Riteau B, Le Gal FA, Avril MF, Dausset J, Guillet JG, Carosella ED. HLA-G expression in melanoma: a way for tumor cells to escape from immunosurveillance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:4510–4515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Amiot L, Ferrone S, Grosse-Wilde H, Seliger B. Biology of HLA-G in cancer: a candidate molecule for therapeutic intervention? Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:417–431. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0583-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hviid TV, Hylenius S, Rørbye C, Nielsen LG. HLA-G allelic variants are associated with differences in the HLA-G mRNA isoform profile and HLA-G mRNA levels. Immunogenetics. 2003;55:63–79. doi: 10.1007/s00251-003-0547-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chen S, Laverdiere I, Tourancheau A, Jonker D, Couture F, Cecchin E, Villeneuve L, Harvey M, Court MH, Innocenti F, et al. A novel UGT1 marker associated with better tolerance against irinotecan-induced severe neutropenia in metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Pharmacogenomics J. 2015;15:513–520. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2015.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Beutler E, Gelbart T, Demina A. Racial variability in the UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1 (UGT1A1) promoter: a balanced polymorphism for regulation of bilirubin metabolism? Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:8170–8174. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.8170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Barbarino JM, Haidar CE, Klein TE, Altman RB. PharmGKB summary: very important pharmacogene information for UGT1A1. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2014;24:177–183. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0000000000000024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hu ZY, Yu Q, Pei Q, Guo C. Dose-dependent association between UGT1A1*28 genotype and irinotecan-induced neutropenia: low doses also increase risk. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:3832–3842. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hu ZY, Yu Q, Zhao YS. Dose-dependent association between UGT1A1*28 polymorphism and irinotecan-induced diarrhoea: a meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:1856–1865. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dias MM, McKinnon RA, Sorich MJ. Impact of the UGT1A1*28 allele on response to irinotecan: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmacogenomics. 2012;13:889–899. doi: 10.2217/pgs.12.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yang H, Sasaki T, Minoshima S, Shimizu N. Identification of three novel proteins (SGSM1, 2, 3) which modulate small G protein (RAP and RAB)-mediated signaling pathway. Genomics. 2007;90:249–260. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lee IK, Kim KS, Kim H, Lee JY, Ryu CH, Chun HJ, Lee KU, Lim Y, Kim YH, Huh PW, et al. MAP, a protein interacting with a tumor suppressor, merlin, through the run domain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;325:774–783. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.10.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wang C, Zhao H, Zhao X, Wan J, Wang D, Bi W, Jiang X, Gao Y. Association between an insertion/deletion polymorphism within 3’UTR of SGSM3 and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:295–301. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-1039-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Savas S, Liu G. Studying genetic variations in cancer prognosis (and risk): a primer for clinicians. Oncologist. 2009;14:657–666. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Röcken C, Lendeckel U, Dierkes J, Westphal S, Carl-McGrath S, Peters B, Krüger S, Malfertheiner P, Roessner A, Ebert MP. The number of lymph node metastases in gastric cancer correlates with the angiotensin I-converting enzyme gene insertion/deletion polymorphism. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:2526–2530. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tang YI, Liu Y, Zhao W, Yu T, Yu H. Caspase-8 polymorphisms and risk of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Exp Ther Med. 2015;10:2267–2276. doi: 10.3892/etm.2015.2832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hengartner MO. The biochemistry of apoptosis. Nature. 2000;407:770–776. doi: 10.1038/35037710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Siegel RM. Caspases at the crossroads of immune-cell life and death. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:308–317. doi: 10.1038/nri1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Halder G, Johnson RL. Hippo signaling: growth control and beyond. Development. 2011;138:9–22. doi: 10.1242/dev.045500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Harvey K, Tapon N. The Salvador-Warts-Hippo pathway - an emerging tumour-suppressor network. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:182–191. doi: 10.1038/nrc2070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pan D. The hippo signaling pathway in development and cancer. Dev Cell. 2010;19:491–505. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Na HK, Lee JY. Molecular Basis of Alcohol-Related Gastric and Colon Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18 doi: 10.3390/ijms18061116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Fernandes GM, Russo A, Proença MA, Gazola NF, Rodrigues GH, Biselli-Chicote PM, Silva AE, Netinho JG, Pavarino ÉC, Goloni-Bertollo EM. CYP1A1, CYP2E1 and EPHX1 polymorphisms in sporadic colorectal neoplasms. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:9974–9983. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i45.9974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Nebert DW, Dalton TP. The role of cytochrome P450 enzymes in endogenous signalling pathways and environmental carcinogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:947–960. doi: 10.1038/nrc2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Pfeifer GP, Denissenko MF, Olivier M, Tretyakova N, Hecht SS, Hainaut P. Tobacco smoke carcinogens, DNA damage and p53 mutations in smoking-associated cancers. Oncogene. 2002;21:7435–7451. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Cury NM, Russo A, Galbiatti AL, Ruiz MT, Raposo LS, Maniglia JV, Pavarino EC, Goloni-Bertollo EM. Polymorphisms of the CYP1A1 and CYP2E1 genes in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma risk. Mol Biol Rep. 2012;39:1055–1063. doi: 10.1007/s11033-011-0831-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lu Y, Zhu X, Zhang C, Jiang K, Huang C, Qin X. Role of CYP2E1 polymorphisms in breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Cell Int. 2017;17:11. doi: 10.1186/s12935-016-0371-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Garziera M, Toffoli G. Inhibition of host immune response in colorectal cancer: human leukocyte antigen-G and beyond. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:3778–3794. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i14.3778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Garziera M, Bidoli E, Cecchin E, Mini E, Nobili S, Lonardi S, Buonadonna A, Errante D, Pella N, D’Andrea M, et al. HLA-G 3’UTR Polymorphisms Impact the Prognosis of Stage II-III CRC Patients in Fluoropyrimidine-Based Treatment. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0144000. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Guo ZY, Lv YG, Wang L, Shi SJ, Yang F, Zheng GX, Wen WH, Yang AG. Predictive value of HLA-G and HLA-E in the prognosis of colorectal cancer patients. Cell Immunol. 2015;293:10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ye SR, Yang H, Li K, Dong DD, Lin XM, Yie SM. Human leukocyte antigen G expression: as a significant prognostic indicator for patients with colorectal cancer. Mod Pathol. 2007;20:375–383. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zeestraten EC, Reimers MS, Saadatmand S, Goossens-Beumer IJ, Dekker JW, Liefers GJ, van den Elsen PJ, van de Velde CJ, Kuppen PJ. Combined analysis of HLA class I, HLA-E and HLA-G predicts prognosis in colon cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:459–468. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gao Y, He Y, Ding J, Wu K, Hu B, Liu Y, Wu Y, Guo B, Shen Y, Landi D, et al. An insertion/deletion polymorphism at miRNA-122-binding site in the interleukin-1alpha 3’ untranslated region confers risk for hepatocellular carcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:2064–2069. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Trabert B, Pinto L, Hartge P, Kemp T, Black A, Sherman ME, Brinton LA, Pfeiffer RM, Shiels MS, Chaturvedi AK, et al. Pre-diagnostic serum levels of inflammation markers and risk of ovarian cancer in the prostate, lung, colorectal and ovarian cancer (PLCO) screening trial. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;135:297–304. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Volonté A, Di Tomaso T, Spinelli M, Todaro M, Sanvito F, Albarello L, Bissolati M, Ghirardelli L, Orsenigo E, Ferrone S, et al. Cancer-initiating cells from colorectal cancer patients escape from T cell-mediated immunosurveillance in vitro through membrane-bound IL-4. J Immunol. 2014;192:523–532. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Koller FL, Hwang DG, Dozier EA, Fingleton B. Epithelial interleukin-4 receptor expression promotes colon tumor growth. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:1010–1017. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Brooks CL, Gu W. p53 ubiquitination: Mdm2 and beyond. Mol Cell. 2006;21:307–315. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Bi H, Tian T, Zhu L, Zhou H, Hu H, Liu Y, Li X, Hu F, Zhao Y, Wang G. Copy number variation of E3 ubiquitin ligase genes in peripheral blood leukocyte and colorectal cancer. Sci Rep. 2016;6:29869. doi: 10.1038/srep29869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Cerhan JR, Liu-Mares W, Fredericksen ZS, Novak AJ, Cunningham JM, Kay NE, Dogan A, Liebow M, Wang AH, Call TG, et al. Genetic variation in tumor necrosis factor and the nuclear factor-kappaB canonical pathway and risk of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:3161–3169. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Chen F, Castranova V, Shi X, Demers LM. New insights into the role of nuclear factor-kappaB, a ubiquitous transcription factor in the initiation of diseases. Clin Chem. 1999;45:7–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.McLure KG, Takagi M, Kastan MB. NAD+ modulates p53 DNA binding specificity and function. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:9958–9967. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.22.9958-9967.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Riley T, Sontag E, Chen P, Levine A. Transcriptional control of human p53-regulated genes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:402–412. doi: 10.1038/nrm2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Sun Y, Zheng W, Guo Z, Ju Q, Zhu L, Gao J, Zhou L, Liu F, Xu Y, Zhan Q, et al. A novel TP53 pathway influences the HGS-mediated exosome formation in colorectal cancer. Sci Rep. 2016;6:28083. doi: 10.1038/srep28083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Brosh R, Rotter V. When mutants gain new powers: news from the mutant p53 field. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:701–713. doi: 10.1038/nrc2693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Siewchaisakul P, Suwanrungruang K, Poomphakwaen K, Wiangnon S, Promthet S. Lack of Association between an XRCC1 Gene Polymorphism and Colorectal Cancer Survival in Thailand. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016;17:2055–2060. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2016.17.4.2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.de Boer JG. Polymorphisms in DNA repair and environmental interactions. Mutat Res. 2002;509:201–210. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(02)00217-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Huang Y, Li X, He J, Chen L, Huang H, Liang M, Zhu Q, Huang Y, Wang L, Pan C, et al. Genetic polymorphisms in XRCC1 genes and colorectal cancer susceptibility. World J Surg Oncol. 2015;13:244. doi: 10.1186/s12957-015-0650-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]