Abstract

Understanding why the quit rate among smokers of menthol cigarettes is lower than non-menthol smokers requires identifying the neurons that are altered by nicotine, menthol, and acetylcholine. Dopaminergic (DA) neurons in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) mediate the positive reinforcing effects of nicotine. Using mouse models, we show that menthol enhances nicotine-induced changes in nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) expressed on midbrain DA neurons. Menthol plus nicotine upregulates nAChR number and function on midbrain DA neurons more than nicotine alone. Menthol also enhances nicotine-induced changes in DA neuron excitability. In a conditioned place preference (CPP) assay, we observed that menthol plus nicotine produces greater reward-related behavior than nicotine alone. Our results connect changes in midbrain DA neurons to menthol-induced enhancements of nicotine reward-related behavior and may help explain how smokers of menthol cigarettes exhibit reduced cessation rates.

Introduction

Menthol cigarettes are used by 1 out of 3 smokers and >85% of African–American smokers (McCarthy et al, 1995). Smokers of menthol cigarettes are less likely to quit compared to smokers of non-menthol cigarettes (Ahijevych and Garrett, 2010). Youth smokers of menthol cigarettes are twice as likely to become lifelong smokers compared to youth smokers of non-menthol cigarettes (D'Silva et al, 2012). With e-cigarettes, consumption rates of flavored products (including menthol) are rising, especially among young smokers (Singh et al, 2016). Thus, it is important that we understand how menthol and other tobacco flavorants alter nicotine reward.

VTA neurons containing α4, α6, and β2 nAChR subunits (α4β2, α4α6β2, α6β2β3) mediate aspects of nicotine addiction (Tapper et al, 2004; Pons et al, 2008). Upregulation of these nAChRs is considered a biomarker for addiction. Smokers of menthol cigarettes exhibit greater upregulation of brain nAChRs compared to smokers of non-menthol cigarettes (Brody et al, 2013). Menthol enhances nicotine withdrawal (Alsharari et al, 2015) and nicotine intravenous self-administration (IVSA) in rats (Wang et al, 2014; Biswas et al, 2016). We have previously reported that menthol alone upregulates α4-containing (α4*) and α6* nAChRs in the VTA and substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) (Henderson et al, 2016). Also, menthol alone alters nAChR function on midbrain DA neurons (Henderson et al, 2016). This suggests that menthol directly alters midbrain neurons, in addition to any sensory and metabolic actions that may increase nicotine exposure in the brain.

Here we demonstrate that menthol plus nicotine enhances nicotine reward-related behavior and nicotine’s actions on midbrain neurons. We suggest that menthol’s ability to enhance nicotine-induced changes in nAChR function, nAChR number, and DA neuron excitability are important for menthol’s enhancement of nicotine reward-related behavior.

Materials and methods

Menthol Dose Selection

We estimated the pharmacologically relevant dose of menthol by analogy with nicotine doses used in mouse studies. Typical menthol cigarettes contain 1–5 mg of menthol (Ai et al, 2015) and ~1 mg of nicotine (Rodgman and Perfetti, 2009). Therefore, menthol is 1–5 times that of nicotine. Steady state and peak concentrations of nicotine in human smokers are replicated in mice using 0.4 and 2.0 mg/kg/h doses of nicotine, respectively (Matta et al, 2007). CPP assays use 0.5 mg/kg nicotine (Tapper et al, 2004). Assays for in vivo upregulation use 2.0 mg/kg/h nicotine (Henderson et al, 2014). We selected 1 mg/kg and 2 mg/kg/h menthol for CPP and in vivo upregulation assays, respectively. Both dose selections fall within the 1–5 menthol-to-nicotine ratio of menthol cigarettes.

We previously discussed our menthol dose selection for cultured cells and neurons (Henderson et al, 2016). In preliminary assays to determine the concentration of menthol in a mouse brain, our chronic dosing methods (2 mg/kg/h, osmotic pump) produced concentrations of menthol at 0.5–2.5 μM. Thus, 500 nM menthol is appropriate in studying cultured neurons and cells and is consistent with previous investigations (Henderson et al, 2016).

All material and methods are described in detail in the Supplementary Material.

Results

Menthol Enhances Nicotine Reward-Related Behavior

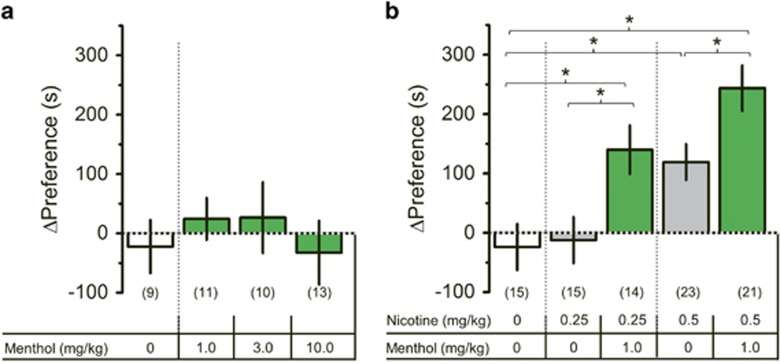

Mice administered with saline or menthol alone (1.0–10 mg/kg) did not exhibit CPP (Figure 1a). Nicotine and menthol plus nicotine produced a significant effect on CPP (Figure 1b, one-way ANOVA, F(4, 83)=14.3, p<0.001). 0.5 mg/kg nicotine produced CPP (p<0.05) (Figure 1b), similar to previous observations (Tapper et al, 2004; Henderson et al, 2016). Menthol (1.0 mg/kg) was administered with either 0.25 mg/kg or 0.5 mg/kg nicotine (Figure 1b). In both pairs, menthol plus nicotine produced a significant increase in CPP compared to respective nicotine-only doses (p<0.05, Figure 1b). This suggests that menthol enhances nicotine reward-related behavior and agrees with previous nicotine IVSA assays (Wang et al, 2014; Biswas et al, 2016).

Figure 1.

Menthol alone is not rewarding but enhances nicotine reward-related behavior. (a and b) Mice were administered saline, menthol, nicotine, or menthol plus nicotine at doses indicated. The data are mean±SEM. *p<0.05, one-way ANOVA, post hoc Tukey. Numbers in parentheses represent number of mice per group.

Menthol Plus Nicotine Alters Baseline Midbrain Neuron Firing Frequency

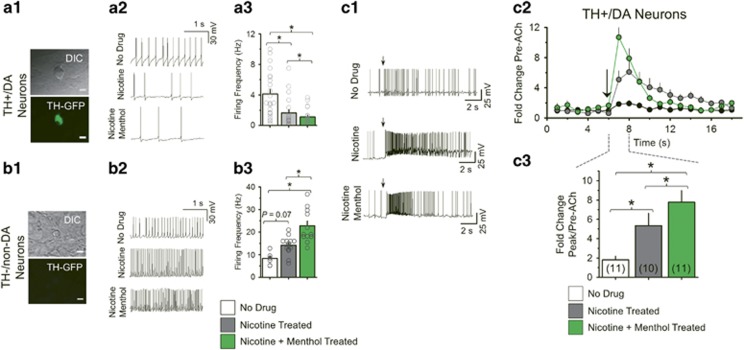

Using midbrain cultures from tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)-eGFP mice, we identified TH+/DA and TH−/non-DA (putative GABA) neurons. Cultured midbrain neurons were treated with control medium (control), 200 nM nicotine, or 500 nM menthol plus nicotine for 10 days. Control TH+/DA neurons exhibited a firing frequency of 4.1±0.7 Hz (Figure 2a1–a3). Drug treatments produced a significant change in firing frequency for TH+/DA (one-way ANOVA, F(2,61)=13.07, p<0.001) and TH−/non-DA neurons (one-way ANOVA, F(2,29)=8.69, p=0.002). Nicotine treatment significantly decreased TH+/DA neuron firing frequency (1.5±0.3 Hz, p<0.005). Menthol plus nicotine decreased TH+/DA neuron firing frequency significantly more than nicotine treatment alone (1.2±0.2 Hz, p<0.05). TH−/non-DA neurons exhibited a baseline firing frequency of 8.1±1.2 Hz (Figure 2b1–b3). Nicotine treatment increased firing frequency (13.9±1.0 Hz, not significant) but menthol plus nicotine increased firing frequency more than nicotine alone (22.4±2.1 Hz, p<0.005).

Figure 2.

Menthol enhances nicotine-induced changes midbrain neuron firing frequency. (a1, b1) Neurons were identified as TH+/DA or TH-/non-DA using TH-eGFP fluorescence. Bars, 20 μm. (a2–3, b2–3, c1–3) Neurons were treated 10 days with control, 200 nM nicotine, or 500 nM menthol plus 200 nM nicotine and firing frequencies were recorded in current clamp mode. (a3, b3) Mean firing frequency of neurons (n=20–22 for TH+/DA neurons and 9–13 for TH−/non-DA neurons). (c1) Current-clamp recordings of TH+/DA neurons before and after ACh puff (100 ms, 300 μM at arrows). (c2) Mean firing frequency over time before and after ACh application. (c3) Mean ‘peak’ firing frequency during 2 s post-ACh puff. For (c1–3), number of neurons recorded is indicated in parenthesis of (c3). The data are mean±SEM: *, p<0.05, one-way ANOVA, post hoc Tukey.

Menthol Enhances nAChR-Stimulated TH+/DA Neuron Excitability

Midbrain TH+/DA neurons exhibit transient increases in firing frequency following nAChR activation, and nicotine’s ability to alter tonic and phasic firing of these TH+/DA neurons is necessary for nicotine reward (Mansvelder et al, 2002). Thus, we examined menthol’s effect on TH+/DA neuron transient increases in firing frequency following nAChR activation.

Neurons were treated for 10 days with control, 200 nM nicotine, or 500 nM menthol plus 200 nM nicotine and were recorded in current clamp mode before and after a brief application of ACh (Figure 2c1–c3). Drug treatments produced a significant effect on TH+/DA neuron excitability (one-way ANOVA, F(2,29)=9.01, p=0.001). After ACh application, control TH+/DA neurons exhibited a transient, ~2-fold increase in firing frequency to 8.0±1.1 Hz (Figure 2c1–c3). Nicotine-treated TH+/DA neurons exhibited a ~5-fold increase in firing frequency, with a maximum of 13.6±2.5 Hz (Figure 2c1–c3). TH+/DA neurons treated with menthol plus nicotine exhibited an ~8-fold increase in firing frequency with a maximum of 19.6±3.1 Hz (Figure 2c1–c3). Thus, we observed that menthol plus nicotine increased firing frequency more than nicotine alone (p<0.05).

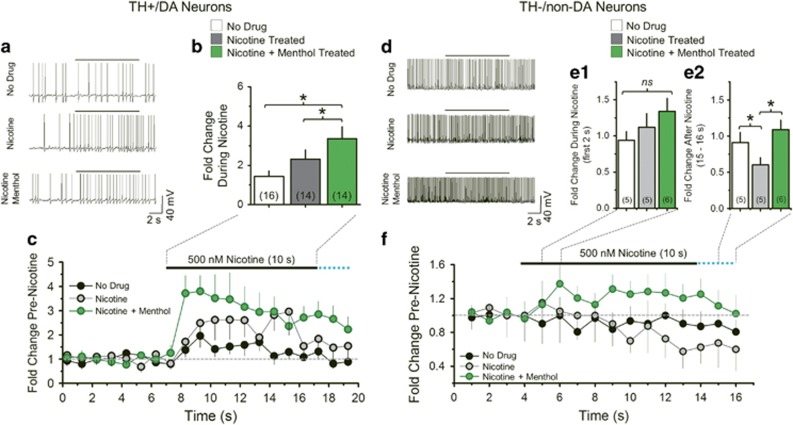

In humans, brain nicotine concentrations peak at ~500 nM seconds after a puff on a cigarette (Matta et al, 2007). Accordingly, we investigated how TH+/DA neuron firing frequency changed during a 10 s exposure to 500 nM nicotine after 10-day treatment with control, nicotine, or menthol plus nicotine (Figure 3). Drug treatment produced a significant effect (one-way ANOVA, F(2,41)=7.29, p=0.002). Control TH+/DA neurons exhibited a transient, 1.4-fold increase in firing frequency during nicotine application. Nicotine-treated TH+/DA neurons exhibited a transient, 2.3-fold increase in firing frequency during nicotine application. TH+/DA neurons treated with menthol plus nicotine exhibited a larger, slowly decaying increase in firing frequency during nicotine application that peaked at 4.0-fold over baseline and was significantly greater than control-treated (p<0.005) or nicotine-treated (p<0.05, Figure 3) TH+/DA neurons.

Figure 3.

Menthol plus nicotine alters neuron excitability during acute exposure to smoking-relevant nicotine concentrations. Neurons were treated 10 days with control, nicotine, or menthol plus nicotine. (a and d) Representative current-clamp traces from TH+/DA and TH−/non-DA neurons puffed with nicotine. (b) Mean change in TH+/DA neuron firing frequency during 10 s nicotine applications. (c) and (f), mean firing frequency over time for TH+/DA and TH−/non-DA neurons, respectively. (e1–2) Mean fold-change in TH−/non-DA firing frequency following the first 2 s of nicotine puff (e1) and 2 s following end of nicotine puff (e2). For (c) and (b), number of individual neurons recorded is indicated in parenthesis in (b). For (f) and (e1–2), number of individual neurons recorded is indicated in parenthesis in (e1-2). The data are mean±SEM. *, p<0.05, one-way ANOVA, post hoc Tukey. Bars indicate 10 s, 500 nM nicotine application and (c, f) dotted blue lines indicate nicotine remains briefly after the end of puff due to perfusion rate.

We completed similar assays on TH−/non-DA neurons (Figure 3d–f). Control-treated TH-/non-DA neurons exposed to acute nicotine (10 s, 500 nM) exhibited no change in firing frequency. Nicotine-treated TH−/non-DA neurons exposed to acute nicotine exhibited an initial increase in firing frequency followed by a significant decrease as the nicotine puff continued (Figure 3e1–e2 and f) (one-way ANOVA, F(2,27)=9.21, p<0.005, Figure 3e2). TH−/non-DA neurons treated with menthol plus nicotine exposed to acute nicotine exhibited a non-significant increase in firing frequency that returned to baseline. We have previously reported that acute applications of menthol (up to 1 μM) do not activate nAChRs or potentiate nAChR currents (Henderson et al, 2016). We also stress that 500 nM menthol failed to alter firing frequency or stimulate inward currents in TH+/DA or TH−/non-DA neurons (Supplementary Figure S1). Thus, the effects we observed result from chronic and not acute actions of menthol.

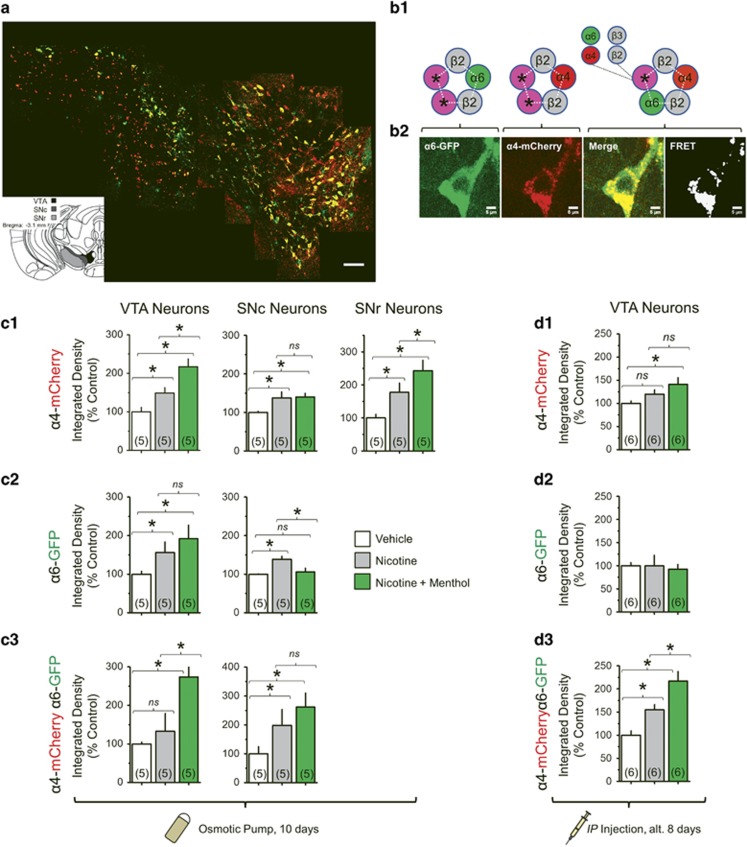

Menthol Enhances Nicotine-Induced Upregulation of α4* But Not α6(non-α4)* nAChRs

Midbrain DA neurons contain α4β2(non-α6)*, α6β2(non-α4)*, and α4α6β2* nAChRs, while midbrain GABA neurons contain α4β2(non-α6)* nAChRs (Champtiaux et al, 2003). These nAChR subtypes are most sensitive to nicotine and are vital for nicotine reward (Pons et al, 2008). To study α4* and α6* nAChR upregulation, we used α4-mCherryα6-GFP mice that were treated for 10 days with vehicle, nicotine (2 mg/kg/h), or menthol plus nicotine (2 mg/kg/h, each). Similar to previous studies (Henderson et al, 2014, 2016), increases in integrated density of GFP or mCherry fluorescence was used to determine change in nAChR number. In midbrain, α6* nAChRs are selectively expressed in DA neurons (Mackey et al, 2012), so DA neurons of the SNc and VTA were identified by the presence of α6-GFP fluorescence (Figure 4a and b1–b2).

Figure 4.

Menthol enhances nicotine-induced upregulation. (a) Representative coronal slice (bregma −3.1) with α4-mCherryα6-GFP-labeled neurons in the VTA, SNc, and SNr. Bar, 100 μm. (b1) Potential assemblies of midbrain nAChRs revealed by GFP and mCherry fluorescence. The subunits indicated by * are uncertain (α4, α6, β2, or β3). (b2) Representative α4-mCherryα6-GFP* neurons. (c1–3) α4-mCherry*, α6-GFP*, or α4α6* nAChR-integrated density. The data are mean±SEM, normalized to vehicle. (c1–3) Chronic treatments were 10 days: vehicle, 2 mg/kg/h nicotine, or 2 mg/kg/h nicotine with 2 mg/kg/h menthol. (d1–3) Mice were given drug dosing identical to CPP assays. Number of mice for each treatment is indicated in parenthesis. *p<0.05, one-way ANOVA, post hoc Tukey.

We observed a significant effect of drug treatment on α4-mCherry and α6-GFP fluorescence intensity in the VTA (one-way ANOVA: F(2,12)=24.1, p<0.001 and F(2,12)=5.43, p=0.017, α4-mCherry and α6-GFP, respectively) and SNc (one-way ANOVA: F(2,12)=4.14, p=0.043 and F(2,12)=7.87, p=0.007, α4-mCherry and α6-GFP respectively) and substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNr) (one-way ANOVA: F(2,12)=8.68, p=0.005, α4-mCherry). Nicotine treatment robustly increased α4* nAChR number in VTA DA neurons and SNr GABA neurons (Figure 4c1–c3). Menthol plus nicotine produced an increase in α4* nAChRs in these same regions that was significantly greater than nicotine alone (p<0.05). In SNc DA neurons, α4* nAChR number was increased by nicotine (p<0.05) and the addition of menthol yielded no difference. As observed previously (Henderson et al, 2014), nicotine increased α6* nAChR number in VTA and SNc DA neurons (Figure 4c1–c2). In VTA neurons, menthol plus nicotine increased α6* nAChR number but was not different from nicotine treatment alone. In SNc DA neurons, menthol plus nicotine did not increase α6* nAChR number. These data suggest that menthol enhances only α4* nAChR upregulation in VTA DA and SNr GABA neurons, and does not enhance α6* nAChR upregulation.

We observed a similar trend in functional upregulation of nAChRs: nicotine alone upregulates α4* and α6* nAChR function, but menthol plus nicotine provides a further increase in only α4* nAChR function (Supplementary Figure S2). In vitro, we observed that menthol enhanced nicotine-induced upregulation of α4* and not α6* nAChRs (Supplementary Figure S3) and the upregulated α4* nAChRs were of the high-sensitivity stoichiometry (Supplementary Figure S4).These data further suggest that menthol may selectively enhance upregulation of α4* and not α6* nAChRs. Using RNA-seq, we found that nAChR upregulation by menthol plus nicotine was not accompanied by any changes in mRNA (Supplementary Figure S3G). Full descriptions of these results can be found in the Supplementary Results section of the Supplementary Material.

Menthol Enhances Nicotine-Induced Upregulation of α4α6* nAChRs

Using pixel-based FRET methods (Henderson et al, 2014), we identified regions where α4-mCherry and α6-GFP nAChR subunits co-assembled to form α4α6* nAChRs (Figure 4b1–b2). Drug treatment produced a significant effect on α4α6* nAChR number in the VTA (one-way ANOVA: F(2,12)=14.4, p<0.001) and SNc (one-way ANOVA: F(2,12)=8.23, p=0.006). In the VTA, α4α6* nAChR number did not significantly increase following nicotine treatment, but menthol plus nicotine significantly increased α4α6* nAChR number (Figure 4c1). In the SNc, nicotine and menthol plus nicotine increased α4α6* nAChR number to a similar extent (Figure 4c2).

Next, we examined whether menthol potentiated nicotine-induced nAChR upregulation on VTA DA neurons under the same drug exposure conditions as our CPP assays. α4-mCherryα6-GFP mice were given injections of saline, nicotine, or menthol plus nicotine, with dosing identical to CPP assays (presented in Figure 1). Because VTA DA neurons are critical for nicotine reward (Pons et al, 2008), we examined only VTA DA neurons (Figure 4d1–d3). We observed a significant effect on α4* nAChRs (F(2,15)=3.90, p=0.04, Figure 4d1). Nicotine produced 20.1% increase in α4* nAChR number (not significant), while menthol plus nicotine produced a 41.3% increase (p<0.05). We observed no change in α6* nAChR number (Figure 4d2). These less-robust observations with alternating daily injections, compared to osmotic pumps, agreed with previous observations of nAChR upregulation.

We observed a significant effect on α4α6* nAChR number (F(2,15)=15.7, p<0.001, Figure 4d3). Nicotine produced a 54.7% increase (p<0.05), while menthol plus nicotine produced a 117.6% increase (p<0.005). The increased α4α6* nAChR number in VTA neurons is accounted for by an increased number of FRET pixels, rather than by increased fluorescence intensity. This was consistent in both osmotic pump and injected preparations.

Discussion

Individual deletions of α4, α6, or β2 nAChR subunits prevent self-administration of nicotine in mice; and selective re-expression of these deleted subunits in the VTA (not SNc or SNr) re-instates self-administration (Pons et al, 2008). Selective activation of α6β2* or α4β2* nAChRs by smoking-relevant concentrations of nicotine stimulates depolarization and elevates firing frequency of VTA DA neurons (Liu et al, 2012; Engle et al, 2013). Both α4 and α6 nAChR subunits are necessary for this as preparations lacking either α4 or α6 nAChR subunits failed to stimulate depolarization or elevate VTA DA neuron firing in response to nicotine. Together, these data highlight VTA α4α6β2* nAChRs as the primary targets of smoking-relevant concentrations of nicotine.

We observed a significant increase in α4α6β2* nAChR number following menthol plus nicotine treatment, greater than the increase observed with nicotine alone (Figure 4c3 and d3). In assays using alternating daily injections, we observed little or no increase in total α4* or α6* nAChRs (Figure 4d1–d2). Considering the increase in α4α6* nAChRs, detected primarily by an increase in FRET pixels, this suggests that nicotine and menthol plus nicotine selectively upregulate the rather small, highly nicotine-sensitive subpopulation of nAChRs that contain both α4 and α6 subunits. Note that our brain slice microscopy method measures both intracellular and plasma membrane nAChRs and is not a direct measurement of functional nAChRs.

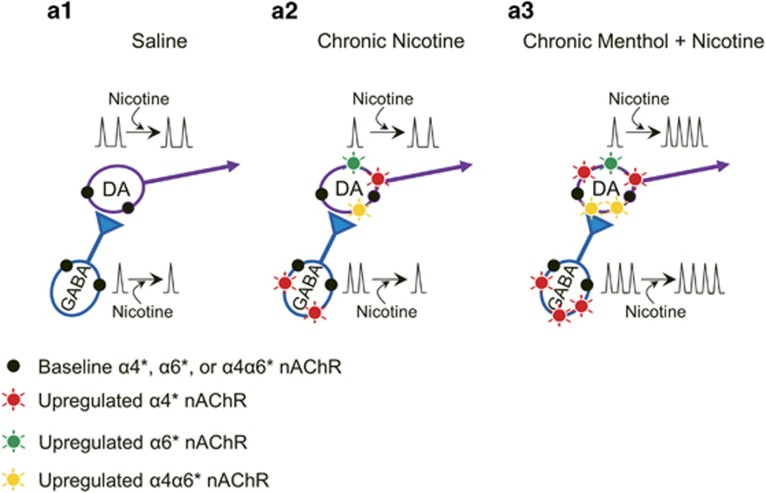

If α4α6β2* nAChRs are the primary targets of smoking-relevant concentrations of nicotine, their enhanced upregulation by menthol plus nicotine may underlie the enhancement in reward-related behavior (Figure 1b). The enhancement in TH+/DA-neuron firing frequency that we observed with menthol plus nicotine (Figure 3c) also supports this. Liu et al (2012) found that 300 nM nicotine applications elevated VTA DA neuron firing in a biphasic manner where α4(non-α6)β2* nAChRs mediated a rapid, desensitizing response and α4α6β2* mediated a sustained elevation in firing. We did observe robust, sustained increases in TH+/DA-neuron firing with similar nicotine applications. This may be attributed to the upregulated α4α6β2* nAChRs. GABAergic inputs on VTA neurons also play an important role in nicotine’s actions. Following chronic exposure to nicotine, α4* nAChRs are upregulated on SNr GABAergic neurons (Figure 4)(Nashmi et al, 2007). Acute nicotine exposure enhances GABAergic activity transiently, followed by sustained depression due to the upregulated α4* nAChRs’ rapid desensitization, leading to increased DA neuron excitability (Mansvelder et al, 2002). In TH−/non-DA neurons, we did measure transient increases in firing, followed by a maintained depression in activity (Figure 3f) in agreement with Mansvelder et al. TH-/non-DA neurons treated with menthol plus nicotine did not decrease in firing frequency during nicotine applications. We have previously observed that menthol (alone) reduces α4β2* nAChR desensitization (Henderson et al, 2016). This may explain how TH-/non-DA neurons may fail to desensitize during nicotine applications as they have only α4(non-α6)β2* nAChRs. These observations are summarized in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Summary. Simplified circuit diagram showing GABAergic neurons (blue) projecting to VTA DA neurons (purple). Arrows indicate acute applications of nicotine and its effect on firing frequency. See discussion for complete description.

Comparing menthol alone (Henderson et al, 2016) to menthol plus nicotine (studied here), we observe a distinct difference. Menthol alone upregulates low-sensitivity α4* and α6* nAChRs, suppresses DA neuron excitability, and suppresses nicotine reward-related behavior. Menthol plus nicotine enhances DA neuron excitability and nicotine reward-related behavior (Figures 1,2,3). The likely molecular basis is that menthol plus nicotine increases the number of high-sensitivity α4* and α6* nAChRs, but menthol alone upregulates low-sensitivity α4* and α6* nAChRs (Supplementary Figure S4 and Henderson et al, 2016).

We note that smokers experience odorant and tastant effects of menthol. It was shown that menthol decreases oral nicotine aversion in mice through a TRPM8-dependent mechanism (Fan et al, 2016). We stress that our results presented here use a drug exposure paradigm that avoids tastant effects and the neurons in our preparations (slices or cultures) do not contain TRPM8 receptors (Henderson et al, 2016). We suggest that tastant and sensory effects act in addition to the direct, neuron-mediated effects we observed.

We provide a cellular basis for how menthol may enhance nicotine reward-related behavior. Our findings, combined with the knowledge that menthol may enhance nicotine withdrawal (Alsharari et al, 2015) and nicotine IVSA (Wang et al, 2014; Biswas et al, 2016), may provide insight into why smokers of menthol cigarettes report lower quit rates.

Funding and disclosure

This work was supported by fundings from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (DA040047, DA033721, DA036061, DA037161, and DA037743).The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Neuropsychopharmacology website (http://www.nature.com/npp)

Supplementary Material

References

- Ahijevych K, Garrett BE (2010). The role of menthol in cigarettes as a reinforcer of smoking behavior. Nicotine Tob Res 12(Suppl 2): S110–S116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ai J, Taylor KM, Lisko JG, Tran H, Watson CH, Holman MR (2015). Menthol content in US marketed cigarettes. Nicotine Tob Res 18: 1575–1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsharari SD, King JR, Nordman JC, Muldoon PP, Jackson A, Zhu AZX et al (2015). Effects of menthol on nicotine pharmacokinetic, pharmacology and dependence in mice. PloS ONE 10: e0137070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas L, Harrison E, Gong Y, Avusula R, Lee J, Zhang M et al (2016). Enhancing effect of menthol on nicotine self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology 233: 3417–3427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody A, Mukhin A, La Charite J, Ta K, Farahi J, Sugar C et al (2013). Up-regulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in menthol cigarette smokers. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 16: 957–966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC (2016). Tobacco use among middle and high school students - United States, 2011 - 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 65: 361–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champtiaux N, Gotti C, Cordero-Erausquin M, David DJ, Przybylski C, Lena C et al (2003). Subunit composition of functional nicotinic receptors in dopaminergic neurons investigated with knock-out mice. J Neurosci 23: 7820–7829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Silva J, Boyle RG, Lien R, Rode P, Okuyemi KS (2012). Cessation outcomes among treatment-seeking menthol and nonmenthol smokers. Am J Prev Med 43: S242–S248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engle SE, Shih PY, McIntosh JM, Drenan RM (2013). Alpha4alpha6beta2* nicotinic acetylcholine receptor activation on ventral tegmental area dopamine neurons is sufficient to stimulate a depolarizing conductance and enhance surface AMPA receptor function. Mol Pharmacol 84: 393–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan L, Balakrishna S, Jabba SV, Bonner PE, Taylor SR, Picciotto MR et al (2016). Menthol decreases oral nicotine aversion in C57BL/6 mice through a TRPM8-dependent mechanism. Tob Control 0: 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson BJ, Srinivasan R, Nichols WA, Dilworth CN, Gutierrez DF, Mackey ED et al (2014). Nicotine exploits a COPI-mediated process for chaperone-mediated up-regulation of its receptors. J Gen Physiol 143: 51–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson BJ, Wall T, Henley BM, Kim CH, Nichols WA, Moaddel R et al (2016). Menthol alone upregulates midbrain nAChRs, alters nAChR sybtype stoichiometry, alters dopamine neuron firing frequency, and prevents nicotine reward. J Neurosci 36: 2957–2974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Zhao-Shea R, McIntosh JM, Gardner PD, Tapper AR (2012). Nicotine persistently activates ventral tegmental area dopaminergic neurons via nicotinic acetylcholine receptors containing alpha4 and alpha6 subunits. Mol Pharmacol 81: 541–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackey ED, Engle SE, Kim MR, O'Neill HC, Wageman CR, Patzlaff NE et al (2012). α6* nicotinic acetylcholine receptor expression and function in a visual salience circuit. J Neurosci 32: 10226–10237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansvelder HD, Keath JR, McGehee DS (2002). Synaptic mechanisms underlie nicotine-induced excitability of brain reward areas. Neuron 33: 905–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matta SG, Balfour DJ, Benowitz NL, Boyd RT, Buccafusco JJ, Caggiula AR et al (2007). Guidelines on nicotine dose selection for in vivo research. Psychopharm 190: 269–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy WJ, Caskey NH, Jarvik ME, Gross TM, Rosenblatt MR, Carpenter C (1995). Menthol vs nonmenthol cigarettes: effects on smoking behavior. Am J Public Health 85: 67–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nashmi R, Xiao C, Deshpande P, McKinney S, Grady SR, Whiteaker P et al (2007). Chronic nicotine cell specifically upregulates functional α4* nicotinic receptors: basis for both tolerance in midbrain and enhanced long-term potentiation in perforant path. J Neurosci 27: 8202–8218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pons S, Fattore L, Cossu G, Tolu S, Porcu E, McIntosh JM et al (2008). Crucial role of α4 and α6 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits from ventral tegmental area in systemic nicotine self-administration. J Neurosci 28: 12318–12327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgman A, Perfetti TA (2009) The Chemical Components of Tobacco and Tobacco Smoke. CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Tapper AR, McKinney SL, Nashmi R, Schwarz J, Deshpande P, Labarca C et al (2004). Nicotine activation of α4* receptors: sufficient for reward, tolerance and sensitization. Science 306: 1029–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T, Wang B, Chen H (2014). Menthol facilitates the intravenous self-administration of nicotine in rats. Front Behav Neurosci 8: 437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.