To the Editor

As part of the drug development process, combinations utilizing approved or experimental agents are routinely explored. However, developing a rational framework for prioritizing the investigation of specific combination strategies remains challenging, especially with immune-based therapies where absence of single agent efficacy has not precluded mechanism-based synergy observed in combination trials [1, 2]. Multiple myeloma (MM) remains a largely incurable malignancy where treatment emergent drug resistance remains a problem and combination therapies are most effective.

PD-1 blockade can re-invigorate a T cell mediated anti-tumor immune response and has emerged as an important treatment for numerous malignancies[3]. Several observations have suggested that an active cellular immune response may lead to control of myeloma. This includes not only observed durable responses following allogeneic transplant suggestive of a graft versus MM effect[4], but also the presence of plasma cell reactive T cells in MM precursor conditions as well as associations with immunity to stem cell antigens (ex. SOX2) and delayed transition from asymptomatic MM to active disease[5]. MM disease progression has also been associated with immunosuppression of both T cell and NK cell immunity[6]. Programmed death-1 (PD-1) expressing senescent and/or exhausted T cells have been observed with disease activity in MM and PD-1 ligand expression on malignant plasma cells is increased relative to the normal plasma cell counterparts[7]. These observations provide rationale for investigating PD-1 blockade in MM.

We recently completed a multi-center phase I study of the anti-PD1 antibody, nivolumab (Bristol Myers-Squibb, BMS) in 27 patients with multiple myeloma (MM) and lymphoma (CA209-039, NCT01592370) [8]. The clinical data from this study has been reported elsewhere and was notable for remarkable single agent clinical activity in Hodgkin lymphoma, some activity in several types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and a disappointing absence of objective responses in MM[8, 9].

Initial studies with nivolumab suggest the antibody continues to occupy >70% of T cell receptors for 2 months or more, within the clinical dose range and that receptor occupancy decays slowly after approximately 85 days from last dose[10]. Presuming that the long receptor binding of nivolumab is not disease-specific, we sought to explore potential for synergy with other MM treatments through evaluation of clinical responses among individuals that went on to receive anti-myeloma therapy within 100 days of their final dose of nivolumab. We evaluated the clinical characteristics of the twenty-seven MM patients treated on CA209-039 and report on the kinetics of response to standard of care regimens and experimental therapies within 100 days of treatment with nivolumab (Table 1). Twelve of the patients were treated with FDA-approved standard therapies after nivolumab and seven patients went on to receive experimental therapy on another clinical trial. Eight patients did not have clinical response data available or received no subsequent therapy after nivolumab.

Table 1.

Demographics and available response data from next line of therapy after nivolumab. Follow-up data available for 19 of 27 MM patients treated on CA209-039 who received additional therapy during the predicted period of nivolumab PD-1 receptor occupancy. Median Age 63y (range: 32–80), Median prior lines of therapy = 2 (range: 1–9), All patients had treatment exposure to IMiDs prior to study enrollment, 11/19 (58%) patients were IMiD-refractory. 18/19 (95%) of patients were PI-exposed, 12/19 (63%) were PI-refractory, and 14/19 (74%) had prior ASCT. No patients had “quad” (Len/Pom/Bor/Cfz) or “penta” (Len/Pom/Bor/Cfz/Dara) refractory disease at study entry.

| Pt ID | Age Sex | ISS Stage | CG Risk by 2016 IMWG Criteria | Prior lines of therapy | Prior ASCT | BR Nivo | Next line of therapy | BR Next | OS (mo.) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior PI or IMiD Exposure, Non-refractory, n = 3 | ||||||||||

| 1 | 80/F | 1 | High | 2 | N | SD | Len | PR | 49.2 | |

| 2 | 62/M | 1 | Standard | 1 | Y | PD | CyBorD | PR | 13.6 | |

| 3 | 65/F | 2 | High | 2 | Y | PD | Clinical Trial | PR | 15.0 | |

| IMiD-refractory (PD on IMiD, or PD within 60 days), PI sensitive, n = 4 | ||||||||||

| 4 | 52/M | 1 | High | 2 | Y | SD | Len | SD | 42.4 | |

| 5 | 63/M | 1 | Standard | 1 | N | SD | Pom | SD | 37.6 | |

| 6 | 72/F | 1 | Standard | 2 | Y | PD | Clinical Trial | PD | 37.3 | |

| 7 | 61/F | 1 | Standard | 2 | Y | PD | Clinical Trial | PR | 12 | Anti-CD38 antibody |

| PI-Refractory (PD on PI, or PD within 60 days), IMiD sensitive n = 4 | ||||||||||

| 8 | 57/F | 1 | Standard | 2 | Y | PD | Clinical Trial | PD | 35.1 | |

| 9 | 71/F | 1 | Standard | 2 | Y | PD | Bor, Len, Dex | VGPR | 39.9 | |

| 10 | 52/M | 1 | Standard | 3 | N | PD | Pom, Clar, Cy, dex | PR | 25.6 | |

| 11 | 71/M | 3 | Standard | 2 | N | PD | Clinical Trial | SD | NA | |

| Double Refractory (PD on IMiD and PI, or PD within 60 days of IMiD + PI), n= 8 | ||||||||||

| 12 | 52/M | 1 | Standard | 3 | Y | SD | Cfz, Cy, Dex | PR | 49.7 | |

| 13 | 32/M | 1 | Standard | 2 | Y | SD | RT, no further therapy | CR | 49.2 | |

| 14 | 58/M | 2 | Standard | 6 | Y | PD | Lenalidomide | SD | 64 | |

| 15 | 59/F | 1 | Standard | 3 | Y | PD | Len, Bor, Dex | PD | 34.5 | |

| 16 | 70/F | 1 | Standard | 9 | Y | PD | Clinical Trial | PD | 4.1 | |

| 17 | 63/F | 3 | Standard | 3 | Y | PD | Pomalidomide | PD | 4.2 | Died from PD |

| 18 | 73/F | 1 | High | 1 | Y | PD | Pom, Cy, Dex | VGPR | 38.5 | |

| 19 | 69/F | 1 | Standard | 8 | N | SD | Clinical Trial | PD | 4 | Anti-CD38 antibody |

ASCT = autologous stem cell transplant, Bor = Bortezomib, BR = Best Response, Cfz = Carfilzomib, Clar = Clarithromycin, Cy = Cyclophosphamide, D or Dex = Dexamethasone, Len = Lenalidomide, OS = Overall Survival, Pom = Pomalidomide, PD = Progressive Disease, PI = proteasome inhibitor, PR = Partial Response, RT = radiation therapy, SD = Stable Disease, VGPR = Very Good Partial Response, IMiD = Immunomodulatory drug. CG = Cytogenetics Risk Group, High = t(4;14), del (17/17p), t(14;16), t(14;20), nonhyperdiploidy, and gain 1q, Standard = all without high risk cytogenetics.

Data collected included age, number of lines of therapy prior to nivolumab, presence of high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities according to 2016 IMWG consensus criteria [11], stage according to the International Staging System (ISS), prior autologous stem cell transplant, and refractory status to immunomodulatory drugs (IMiD) or proteasome inhibitors (PI) as defined by progression on or within 60 days of exposure to IMiD or PI, respectively. Investigators assessed response according to IMWG criteria[12] for patients that received therapy within 100 days of nivolumab. Safety data was collected and provided by BMS up to 100 days after final treatment with nivolumab for all 27 patients. Data describing PD-1 receptor occupancy (RO) by nivolumab during treatment CA209-039 was provided by BMS.

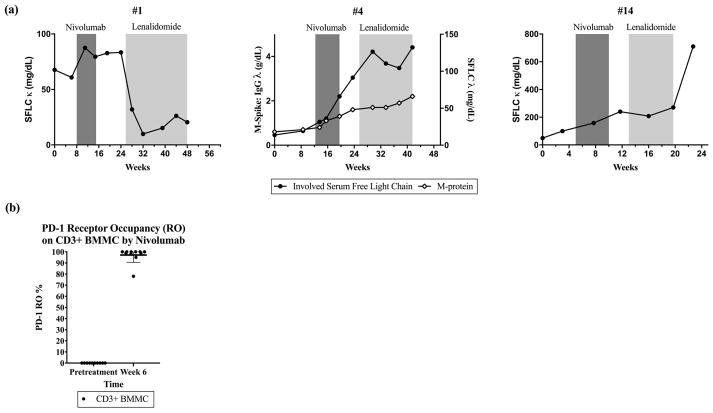

Nivolumab binding to PD-1 molecules on CD3+ bone marrow mononuclear cells (BMMC) collected pretreatment and at week 6 following two doses of nivolumab was evaluated using a flow cytometry based assay optimized from a method previously reported[10]. Briefly, BMMC were pre-incubated (30 minutes at 4°C) with a saturating concentration (50 μg/mL) of either isotype control or nivolumab, washed extensively, and then co-stained with anti-CD3 PerCP and murine anti-human IgG4 PE (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, Alabama). PD-1 receptor occupancy by infused nivolumab was estimated as the ratio of the percent of CD3+ cells stained with anti-human IgG4 after in vitro saturation with isotype control antibody (indicating in vivo binding) to that observed after saturation using nivolumab (indicating total available binding sites). Using mean fluorescence intensity (MFI), the mean PD-1 RO was estimated to be 97.2% on cryopreserved CD3+ BMMC 21 days after the most recent dose of nivolumab and just prior to the patient’s third dose of nivolumab (Figure 1, (b)). RO data was not collected after cessation of nivolumab treatment.

Figure 1.

(a) Involved serum paraprotein markers in 3 patients with relapsed myeloma receiving lenalidomide (without dexamethasone) after treatment with nivolumab. SFLC = serum free light chain

(b) PD-1 receptor occupancy (RO) by nivolumab on CD3+ bone marrow mononuclear cells (BMMC) by mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) before nivolumab and at week 6 of therapy. Patients were treated every 21 days for the first two doses on study, and week 6 BMMC were collected prior to dose #3.

Responses and clinical data for the 19 patients that received additional therapy during the predicted period of nivolumab RO are summarized in Table 1. The objective response rate (ORR) was 47%, with 9 patients achieving a PR or better. Of twelve patients receiving standard of care treatments, seven patients had a response to therapy and achieved a PR or better (55%), two patients reached a VGPR (17%), and one patient who received focal radiation to a bony plasmacytoma that developed while on nivolumab reached a CR (previously reported[8]) that continues, now >30 months.

We observed clinical benefit with IMiDs among IMiD-refractory patients and responses to low dose IMiDs in previously IMiD exposed patients. Three patients went on to receive lenalidomide 10mg for 21 of 28 days without dexamethasone as next line of therapy after nivolumab (Figure 1). Two of these patients had lenalidomide-refractory disease and one had prior exposure to thalidomide. The thalidomide-exposed patient (#1) had a very brisk response to low dose single agent lenalidomide therapy. In the two lenalidomide-refractory patients (#4, #14), we observed disease stabilization using lenalidomide 10mg without dexamethasone lasting for approximately 3 months. This result was unexpected in patients previously refractory to lenalidomide, and may suggest a potential interaction during a period of predicted residual receptor binding of PD-1 by nivolumab. Out of the nineteen patients with available follow-up data, seven patients went on to participate in clinical studies and two received an anti-CD38 antibody on a clinical study. After treatment with anti-CD38 after nivolumab, an IMiD-refractory patient with two prior lines of therapy achieved a PR, and a heavily pre-treated patient with 8 prior lines of therapy had PD.

To evaluate for a signal of excess toxicity from nivolumab and subsequent therapy, toxicity data was collected for all twenty-seven patients who participated in CA209-039. Three patients had drug-related adverse events for which anti-PD1 therapy was discontinued and not resumed. In the first 30 days after treatment discontinuation, eight patients had adverse events attributed to anti-PD1 therapy, fifteen of twenty-one events were grade 1–2 in severity (71.4%), and there were six grade 3 events (28.6%), with one case of grade 3 pneumonitis noted. Delayed toxicity related to therapy (onset of adverse event within 30–100 days from last treatment with nivolumab) was limited to hematologic toxicity, with one instance of grade 3 anemia, and one episode of grade 2 pancytopenia. In the first 30 days after discontinuing treatment, seven patients had non-hematologic AEs related to drug therapy. There was no grade 4 or 5 toxicity related to therapy. In this anecdotal evaluation, enhanced toxicity with the next line of therapy during the expected period of nivolumab RO was not apparent.

This case series lends support to the hypothesis that PD-1 blockade may synergize with other antimyeloma therapy through mechanisms that remain to be determined. This observation is consistent with emerging promising clinical data utilizing anti-PD-1 agents in combination with IMiDs and dexamethasone[13, 14, 15]. An ongoing CR in a patient with double-refractory MM who received radiation to a focal plasmacytoma during the predicted period of PD-1 receptor occupancy by nivolumab suggests the possibility of abscopal effects and we believe warrants further investigation. Although our observations reported here are drawn from a small cohort of patients and are hypothesis-generating in nature, responses we noted to the next therapy immediately after nivolumab support carrying out clinical studies exploring novel combinations of PD-1 pathway blockade with anti-myeloma therapies. Several studies of anti-myeloma drugs used in combination with immune checkpoint blockade are planned or underway (NCT02331386, NCT02576977, NCT02880228 NCT02036502, NCT02331368, NCT02685826, NCT02616640). Correlative analyses of these studies are needed to elucidate the mechanisms that underscore any emerging observations of additive effects of PD-1 pathway blockade concurrent with IMiDs, MM-targeted monoclonal antibodies, or radiation therapy.

Acknowledgments

Funding:

This work was supported in part by the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) NCI core [grant P30 CA008748] (A.M.L.). M.J.P. is supported in part by the MSKCC Mortimer J. Lacher Fellowship supported by the Lymphoma Foundation and also supported in part by a grant from the NIH/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR00457), administered by the Clinical and Translational Science Center at Weill Cornell Medical Center and MSKCC. A.M.L. is a member of the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy, which supported the MSKCC Cancer Immunotherapy Program. A.M.L. also receives support from the MSK Sawiris Foundation and Cycle For Survival.

We would like to thank the patients and their families for their participation in this clinical study. We would like to thank Katherine Yang and Benedetto Farsaci for for providing receptor occupancy data, and Payal Parikh-Patel, Mihaela Popa McKiver, and Brian Lestini of Bristol-Myers Squibb for their critical review of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosure of interest:

A.M.L. reported research funding from BMS, Janssen, Genentech, and Serametrix, Consulting/Honoraria from Syndax, Aduro, Juno, Oncomed, BMS, Novartis, Janssen, and royalties from Serametrix. S.A.F. has stock ownership in Kite Pharma, D.B.P. reported research support from Medimmune, Merck, and IRX Therapeutics, and consultancy for Peregrine and Celgene. S.M.A. reported research funding from BMS, Merck, Seattle Genetics and Affimed. I.M.B. reported BMS research funding and consultancy. E.C.S. and M.G. reported BMS research funding. H.H. reported Takeda Consultancy and Research Funding; Celgene Research funding; Novartis Consultancy. M.J.P., D.C., N.L., and C.O.L. have no relevant disclosures.

References

- 1.Zonder JA, Mohrbacher AF, Singhal S, van Rhee F, Bensinger WI, Ding H, Fry J, Afar DE, Singhal AK. A phase 1, multicenter, open-label, dose escalation study of elotuzumab in patients with advanced multiple myeloma. Blood. 2012;120:552–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-360552. Epub 2011/12/21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lonial S, Dimopoulos M, Palumbo A, White D, Grosicki S, Spicka I, Walter-Croneck A, Moreau P, Mateos MV, Magen H, Belch A, Reece D, Beksac M, Spencer A, Oakervee H, Orlowski RZ, Taniwaki M, Rollig C, Einsele H, Wu KL, Singhal A, San-Miguel J, Matsumoto M, Katz J, Bleickardt E, Poulart V, Anderson KC, Richardson P Investigators E. Elotuzumab Therapy for Relapsed or Refractory Multiple Myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:621–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1505654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lesokhin AM, Callahan MK, Postow MA, Wolchok JD. On being less tolerant: Enhanced cancer immunosurveillance enabled by targeting checkpoints and agonists of T cell activation. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:280sr1. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3010274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bensinger WI, Maloney D, Storb R. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. Seminars in hematology. 2001;38:243–9. doi: 10.1016/s0037-1963(01)90016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dhodapkar MV, Sexton R, Das R, Dhodapkar KM, Zhang L, Sundaram R, Soni S, Crowley JJ, Orlowski RZ, Barlogie B. Prospective analysis of antigen-specific immunity, stem-cell antigens, and immune checkpoints in monoclonal gammopathy. Blood. 2015;126:2475–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-03-632919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guillerey C, Nakamura K, Vuckovic S, Hill GR, Smyth MJ. Immune responses in multiple myeloma: role of the natural immune surveillance and potential of immunotherapies. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73:1569–89. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2135-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung DJ, Pronschinske KB, Shyer JA, Sharma S, Leung S, Curran SA, Lesokhin AM, Devlin SM, Giralt SA, Young JW. T-cell Exhaustion in Multiple Myeloma Relapse after Autotransplant: Optimal Timing of Immunotherapy. Cancer immunology research. 2016;4:61–71. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lesokhin AM, Ansell SM, Armand P, Scott EC, Halwani A, Gutierrez M, Millenson MM, Cohen AD, Schuster SJ, Lebovic D, Dhodapkar M, Avigan D, Chapuy B, Ligon AH, Freeman GJ, Rodig SJ, Cattry D, Zhu L, Grosso JF, Bradley Garelik MB, Shipp MA, Borrello I, Timmerman J. Nivolumab in Patients With Relapsed or Refractory Hematologic Malignancy: Preliminary Results of a Phase Ib Study. J Clin Oncol. 2016 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.9789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ansell SM, Lesokhin AM, Borrello I, Halwani A, Scott EC, Gutierrez M, Schuster SJ, Millenson MM, Cattry D, Freeman GJ, Rodig SJ, Chapuy B, Ligon AH, Zhu L, Grosso JF, Kim SY, Timmerman JM, Shipp MA, Armand P. PD-1 blockade with nivolumab in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:311–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brahmer JR, Drake CG, Wollner I, Powderly JD, Picus J, Sharfman WH, Stankevich E, Pons A, Salay TM, McMiller TL, Gilson MM, Wang C, Selby M, Taube JM, Anders R, Chen L, Korman AJ, Pardoll DM, Lowy I, Topalian SL. Phase I study of single-agent anti-programmed death-1 (MDX-1106) in refractory solid tumors: safety, clinical activity, pharmacodynamics, and immunologic correlates. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3167–75. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.7609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sonneveld P, Avet-Loiseau H, Lonial S, Usmani S, Siegel D, Anderson KC, Chng WJ, Moreau P, Attal M, Kyle RA, Caers J, Hillengass J, San Miguel J, van de Donk NW, Einsele H, Blade J, Durie BG, Goldschmidt H, Mateos MV, Palumbo A, Orlowski R. Treatment of multiple myeloma with high-risk cytogenetics: a consensus of the International Myeloma Working Group. Blood. 2016;127:2955–62. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-01-631200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rajkumar SV, Harousseau JL, Durie B, Anderson KC, Dimopoulos M, Kyle R, Blade J, Richardson P, Orlowski R, Siegel D, Jagannath S, Facon T, Avet-Loiseau H, Lonial S, Palumbo A, Zonder J, Ludwig H, Vesole D, Sezer O, Munshi NC, San Miguel J International Myeloma Workshop Consensus P. Consensus recommendations for the uniform reporting of clinical trials: report of the International Myeloma Workshop Consensus Panel 1. Blood. 2011;117:4691–5. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-299487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Badros A, Kocoglu MH, Ma N, Rapoport AP, Lederer E, Philip S, Lesho P, Dell C, Hardy NM, Yared J, Goloubeva O, Singh Z. A Phase II Study of Anti PD-1 Antibody Pembrolizumab, Pomalidomide and Dexamethasone in Patients with Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma (RRMM). Oral Abstract presented at: American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting; 2015 December 7; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 14.San Miguel J, Mateos MV, Shah JJ, Ocio EM, Rodriguez-Otero P, Reece D, Munshi NC, Avigan D, Ge Y, Balakumaran A, Marinello P, Orlowski R, Siegel D. Pembrolizumab in Combination with Lenalidomide and Low-Dose Dexamethasone for Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma (RRMM): Keynote-023. Oral Abstract presented at: American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting; 2015 December 7; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Badros A, Hyjek E, Ma N, Lesokhin A, Rapoport AP, Kocoglu MH, Lederer E, Philip S, Lesho P, Johnson A, Dell C, Goloubeva O, Singh Z. Pembrolizumab in Combination with Pomalidomide and Dexamethasone for Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma (RRMM). Oral Abstract presented at: American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting; 2016 December 4th; 2016. [Google Scholar]