Abstract

We conducted a prospective phase I study to evaluate safety of an orally administered Salmonella encoding IL‐2 (SalpIL2) in combination with amputation and adjuvant doxorubicin for canine appendicular osteosarcoma. Efficacy was assessed as a secondary measure. The first dose of SalpIL2 was administered to 19 dogs on Day 0; amputation was done after 10 days with chemotherapy following 2 weeks later. SalpIL2 was administered concurrent with chemotherapy, for a total of five doses of doxorubicin and six doses of SalpIL2. There were six reportable events prior to chemotherapy, but none appeared due to SalpIL2. Dogs receiving SalpIL2 had significantly longer disease‐free interval (DFI) than a comparison group of dogs treated with doxorubicin alone. Dogs treated using lower doses of SalpIL2 also had longer DFI than dogs treated using the highest SalpIL2 dose. The data indicate that SalpIL2 is safe and well tolerated, which supports additional testing to establish the potential for SalpIL2 as a novel form of adjuvant therapy for dogs with osteosarcoma.

Keywords: canine, immunotherapy, Interleukin‐2, osteosarcoma, Salmonella

Introduction

Osteosarcoma is the most common primary bone tumour of dogs (Bailey et al. 2003). Current standard of care for the treatment of canine appendicular osteosarcoma involves removal of the primary tumour (amputation or limb sparing surgery) followed by adjuvant chemotherapy (Berg et al. 1995; Bell et al. 2015). The median overall survival (OS) time for dogs treated with surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy ranges from 235 to 479 days and the median disease‐free interval (DFI) ranges from 135 to 435 days (Greco et al. 2003; Dow et al. 2005; Coburn et al. 2007; Crull et al. 2011; Ehrhart et al. 2013; Fenger et al. 2014). Despite the use of various chemotherapy protocols, the prognosis for dogs with appendicular osteosarcoma remains poor. In order to improve survival of dogs with osteosarcoma without increasing morbidity, safe and more effective therapies are needed.

Interleukin‐2 (IL‐2) is a pleiotropic cytokine released early during an immune response (Haagsman et al. 2013). A property that has made IL‐2 attractive as the basis for cancer immunotherapy, is enhancement of the tumoricidal capacity of lymphoid cells, specifically T lymphocytes and natural killer cells (Helfand et al. 1992). IL‐2 has several potential uses in cancer therapy including: the augmentation of specific T‐cell‐mediated anti‐tumour immunity and the activation of non‐specific cytolytic effector cells, termed lymphokine‐activated killer (LAK) cells (Helfand et al. 1994a). Use of IL‐2 has shown success in treatment of metastatic melanoma and renal cell carcinoma and is part of the standard of care for these diseases in human patients (Helfand et al. 1994b). The canine and human IL‐2 proteins are evolutionarily conserved (87% conservation and 75% identity at the amino acid sequence), and human IL‐2 binds canine IL‐2 receptors and has biological activity in dogs in vivo (Jia et al. 2007; Krick et al. 2012; Lane et al. 2012). In dogs, IL‐2 has been shown to have clinical efficacy against soft tissue sarcomas and osteosarcoma (Mengesha et al. 2006; Liao et al. 2013). However, severe dose‐limiting toxicities are associated with systemic administration of IL‐2 to humans and dogs, including fever, nausea, jaundice, capillary leak syndrome and death (Lane et al. 2012; Modiano et al. 2012). One approach to maintain the efficacy of IL‐2‐based immunotherapies while limiting systemic toxicity is to use biologic vectors that can deliver the cytokine directly to the local tumour environment (Morrisse et al. 2010).

Salmonella spp. are Gram‐negative, intracellular, facultative anaerobic bacteria that can cause a wide spectrum of diseases in humans and animals (Patyar et al. 2010). Following oral administration, Salmonella colonize the liver, spleen and lymph nodes (Phillips et al. 2009). The innate biodistribution properties and affinity for hypoxic or anaerobic environments, such as those found in tumours (Saltzman et al. 1996; Rosenberg 2014), make these bacteria suitable delivery vectors for molecules such as IL‐2 that can mediate tumour immunotherapy (Schodel et al. 1994; Saltzman et al. 1997a,b). This is the basis for the generation of SalpIL2, an avirulent, but highly immunogenic Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium strain engineered to act as a systemic delivery vector for IL‐2‐based tumour immunotherapy (Schwartz et al. 2002; Phillips et al. 2009; Morrisse et al. 2010; Selmic et al. 2014).

Oral delivery of Salmonella transfected with a plasmid construct with a truncated gene for human IL‐2 (Selmic et al. 2014), is associated with lower adverse events than intravenous dosing in laboratory animals, and it is a major innovative step in this technology. In laboratory animals, the maximum tolerated dose for the most widely used intravenous formulation of Salmonella, called VNP20009, is 106 cfu/mouse (Sim & Radvanyi 2014).In contrast, the oral approach takes advantage of the unique propensity of Salmonella to track tumour tissues in vivo, while also colonizing liver and spleen where SalpIL2 induces enhanced immune responses to tumours with no evidence of severe adverse events even when used at 108 cfu/mouse, which is two orders of magnitude higher than the MTD for VNP20009 (Sorenson et al. 2008a; Skorupski et al. 2016). Intravenous VNP20009 has also been used in dogs and humans with spontaneous tumours (Sorenson et al. 2008b, 2010). Objective responses were seen in six out of 35 dogs treated, including a partial response in one out of four dogs with osteosarcoma, but none were observed in 24 human patients with metastatic melanoma or in one patient with metastatic renal carcinoma (Sorenson et al. 2008b, 2010). However, severe, dose‐limiting toxicities occurred in both dogs and humans with spontaneous cancer, establishing maximal tolerated doses of 3 × 10 7 cfu/kg for dogs (Sorenson et al. 2008b) and 3 × 108 cfu/m2 in humans (Sorenson et al. 2010).

The safety margin of SalpIL2, combined with its preference for colonization of cultured osteosarcoma cells as compared, for example, to hepatocellular carcinoma and neuroblastoma cells and its capacity to reduce the metastatic potential of osteosarcoma in mouse models (Soto et al. 2003), supported translation of SalpIL2 to dogs with spontaneous osteosarcoma (Soto et al. 2004).

For this study, we hypothesized that oral SalpIL2 administered with standard of care (amputation and adjuvant chemotherapy) would be safe and well tolerated in dogs with non‐metastatic appendicular osteosarcoma. We specifically designed and implemented this phase I dose escalation study to evaluate safety (hypothesis testing), and to assess efficacy as a secondary measure (hypothesis generating).

Materials and methods

Participant selection

Client‐owned dogs presented to the University of Minnesota, Veterinary Medical Center (VMC) with previously untreated osteosarcoma underwent initial screening followed by procurement of signed owner informed consent. All enrolled dogs had histologic confirmation of appendicular osteosarcoma. Inclusion criteria included dogs of any age, weighing between 20–70 kg, without evidence of gross metastasis on thoracic radiographs, and whose owners agreed to follow through with standard care that included amputation of the affected limb plus adjuvant chemotherapy using doxorubicin. To avoid potential confounders for our assessment of shedding into the environment during therapy, a negative faecal culture for Salmonella was also required for eligibility. Dogs were excluded from study participation if they had evidence of gross metastasis or concurrent illness.

Data collected for each dog included signalment, weight, tumour location, pre‐ and post‐amputation total serum alkaline phosphatase, chemotherapy toxicity, dose reductions, treatment delays, outcome, rescue therapy, cause of death and necropsy information, if available. Tumour location was based on radiographic reports, and for classification purposes, tumours were categorized as located in the distal radius, proximal humerus, distal femur, distal tibia or other location. All radiographs were taken at the VMC and were reviewed by a board‐certified radiologist. Total serum alkaline phosphatase activity was classified as normal or elevated based on the VMC laboratory reference range. Adverse chemotherapy‐related toxicity was graded using the Veterinary Cooperative Oncology Group common terminology criteria for adverse events (VCOG‐CTCAE) v 1.0 (Spodnick et al. 1992). Two historical control groups of dogs from the University of Minnesota VMC were used for comparison. These dogs were treated between the years 2003 to 2014 and had appendicular osteosarcoma that was staged, evaluated, and treated with five doses of doxorubicin alone (30 mg/m2, i.v.) or three doses of each carboplatin (300 mg/m2, i.v.) and doxorubicin on an alternating schedule. We chose the past 10 years as our comparison group since numerous chemotherapeutic protocols have been described during this time period for the adjuvant treatment of appendicular osteosarcoma but, despite this, there is no consensus as to the optimal protocol. All of the study dogs and comparison groups were staged every month for the first 3 months and then every 3 months thereafter.

Trial design

The clinical protocol was approved by the University of Minnesota Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol 1103A96836). This study was conducted as a prospective, open label, phase I, dose‐cohort (3 + 3) escalation design that investigated the maximally tolerated dose (MTD) and dose‐limiting toxicity (DLT) of neoadjuvant + adjuvant SalpIL2 in dogs with appendicular osteosarcoma treated with the standard of care (amputation and adjuvant doxorubicin‐based chemotherapy) (Table S1) (Straw et al. 1990). Dogs enrolled in the study received an oral dose of SalpIL2 on Day 0 with a starting dose of 1 × 105/dog (cohort 1; Table 1), which was based on laboratory animal data from one of our laboratories (Saltzman). A logarithmic dose escalation was carried out in cohorts of three dogs. Establishment of an MTD would be based on the number of dogs experiencing a DLT, defined as grade ≥ 3 for any adverse event with the exception of haematologic toxicity, where grade 3 neutropenias or thrombocytopenias that resolved before the next scheduled doxorubicin treatment were not deemed to be dose‐limiting. Grade 4 neutropenia or thrombocytopenia was deemed as DLT. If no DLTs were observed in the first cohort of dogs, a second cohort of three dogs was treated at the next higher dose. If a DLT was observed in one dog, the cohort was expanded by an additional three dogs. If ≥2 DLTs were noted in any initial or expanded cohort, no further dose escalations were performed and the MTD was considered to have been reached or exceeded. There were no intra‐dog escalations.

Table 1.

Patient demographics

| Comparison groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | SalpIL2 (n = 19) | Doxorubicin (n = 16) | Alternating doxorubicin and carboplatin (n = 23) |

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean | 7.2 | 7.5 | 6.9 |

| Median | 7.0 | 7.0 | 6.0 |

| Range | 3.5–10 | 2–10.5 | 3.5–9.0 |

| Body weight (kg) | |||

| Mean | 43.8 | 36.9 | 37.3 |

| Median | 38.8 | 35.5 | 35.6 |

| Range | 27.5–70.0 | 22.2–70.2 | 22.3–68.2 |

| Gender | |||

| Male intact | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Male neutered | 12 | 7 | 9 |

| Female intact | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Female spayed | 7 | 9 | 14 |

| Breeds | |||

| Golden retriever | 2 | 3 | 7 |

| Labrador retriever | 8 | 5 | 4 |

| Greyhound | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Saint bernard | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Irish wolfhound | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Siberian husky | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| German shepherd | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| Great pyrenees | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Mastiff | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Rottweiler | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Newfoundland | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Dalmation | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Vizsla | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Boxer | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Doberman pinscher | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Mixed breed | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Location of tumour | |||

| Proximal humerus | 9 | 4 | 5 |

| Distal radius | 3 | 5 | 9 |

| Distal tibia | 5 | 1 | 3 |

| Distal femur | 2 | 6 | 6 |

| Total alkaline phosphatase activity | |||

| Before amputation | |||

| Normal | 16 | 13 | 17 |

| Elevated | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| After amputation | |||

| Normal | 18 | 15 | 19 |

| Elevated | 1 | 1 | 4 |

Day 0 was considered as that day when bone biopsies were collected and the first dose of neoadjuvant SalpIL2 was administered. On days 3 and 7, follow‐up physical examination, complete blood count, serum chemistry, urinalysis and faecal culture were performed. The affected limb was amputated on day 10 after the prescribed delay, and 2 weeks later, dogs received the first dose of doxorubicin (30 mg/m2, i.v.). All doses of adjuvant doxorubicin and SalpIL2 were prescribed at 21‐day intervals (concurrent administration) for a total of five doses of doxorubicin and six doses of SalpIL2. Dose adjustments and treatment delays due to gastrointestinal toxicity or myelosuppression were allowed at the discretion of the treating clinician. Routine monitoring for pulmonary metastasis with thoracic radiographs occurred during therapy at the time of the third chemotherapy dose, at the time of the fifth dose of chemotherapy and every 3 months thereafter. Any reported lameness or bone pain was further evaluated by radiographs of the affected bone.

SalpIL2

Attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium strain χ4550 has mutations in the adenylate cyclase, cyclic adenosine monophosphate receptor protein and aspartate semialdehyde dehydrogenase (asd) genes, which impair its survival and make the organism much less virulent than wild‐type S. Thyphimurium, although it retains its immunogenicity (Thamm et al. 2005). The genetically engineered SalpIL2 was constructed by inserting the human IL‐2 gene into χ4550 downstream in an asd‐based plasmid. This restores the capacity of the organism to survive, but then every surviving Salmonella χ 4550 also must synthesize IL‐2. The bacteria used for the clinical study were grown in Luria broth, and doses of 1 × 105–1 × 109 cfu were encapsulated into double‐cased capsules (CustomRx Compounding Pharmacy, Minneapolis, MN, USA) and stored at −86°C. After frozen storage, capsules thawed and bacterial viability was confirmed by plating serial dilutions in agar. The yields obtained from the frozen capsules were equivalent to the encapsulated doses. The investigational use of S. Typhimurium therapy was approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Biosafety Committee (protocols 1106H00404 and 1306‐30688H).

SalpIL2 dosing

All personnel wore protective equipment when orally administering the SalpIL2. SalpIL2 was given orally to each dog at 21‐day intervals compounded into four double‐cased capsules in a small bolus of food. The initial cohort started at a dose of 1 × 105 cfu/dog and five cohorts were included for escalation up to a dose of 109 cfu/dog, which was approximately equivalent to a clinically active dose of 107 cfu/kg in mice (Toso et al. 2002). The last cohort at this dose was then expanded to include of seven dogs.

Salmonella cultures

Faecal samples were collected weekly until 1 week after completion of the last concurrent dose of doxorubicin and SalpIL2 and submitted to Marshfield Laboratories (Marshfield, WI) for culture to identify the presence of Salmonella sp. Samples were handled using Marshfield's preferred method (https://www.marshfieldlabs.org/sites/ltrm/Vet/Pages/484.aspx). Enrichment of positive faecal cultures was followed by genomic DNA extraction and real‐time PCR assay to target Salmonella species‐specific DNA segments. Samples of tumour tissue were minced and then homogenized in 3 mL of sterile PBS using gentleMACS M Tubes (Miltenyi Biotec: Bengisch Gladbach Germany) with a gentleMACS Tissue Dissociator (program RNA_01). The homogenate was serially diluted in sterile PBS, plated on LB agar and incubated for 16–18 h at 37°C for enumeration of colony forming units (cfu).

Statistical analysis

Kaplan–Meier analysis was used to calculate median DFI and median OS. DFI was calculated as the number of days from the date of diagnosis to the date when metastases were detected. Dogs were censored in the DFI analysis if they did not have documented metastases at the time of last follow‐up or at the time of death when it was due to a cause other than osteosarcoma. OS was defined as the time from diagnosis to death. Dogs were censored in the OS analysis, if they were alive at last follow‐up, lost to follow‐up or if they died from other causes. The log‐rank test was used to compare DFI and OS between the study population and each historical control group.

Cox proportional hazard regression and the Fisher's exact test were used to evaluate associations between baseline characteristics, including age and body weight at diagnosis, breed, previously identified prognostic factors (proximal humeral tumour site and total serum alkaline phosphatase activity) and outcome measures. Statistical analyses were performed using RStudio (Integrated development environment for R (Version 0.98.1091), Boston, MA) and a P‐value of <0.05 was considered significant for all analyses.

Results

Demographic characteristics of study populations

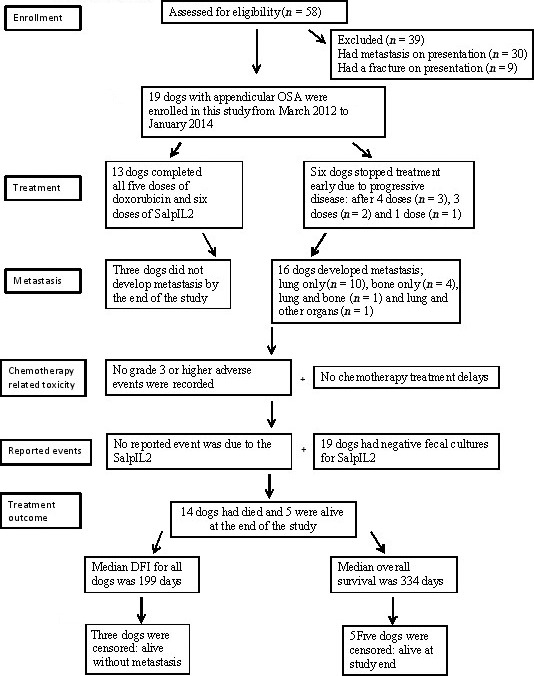

A consort flow diagram with details of enrolment and study design is shown in Fig. 1. Fifty‐eight dogs were screened for eligibility. Thirty‐nine dogs were excluded due to the presence of metastasis or a pathologic fracture at diagnosis. The remaining 19 dogs were enrolled between March 2012 and January 2014.

Figure 1.

A consort flow diagram with details of patient enrolment and study design.

Two separate groups of dogs with non‐metastatic appendicular osteosarcoma treated at the University of Minnesota VMC between 2003 and 2014 were used as comparison groups. Comparison group 1 consisted of 16 dogs treated with amputation plus adjuvant doxorubicin; comparison group 2 consisted of 23 dogs treated with amputation plus three doses each of carboplatin and doxorubicin on an alternating schedule.

The demographic characteristics of the dogs in this study and in the two comparison groups are described in Table 1. There were no significant differences in the demographic characteristics between the study dogs and the two comparison groups, although a greater proportion of dogs had humeral osteosarcoma in the study group (47%) compared with the comparison groups (≤ 25%).

Assessment of safety

The study was designed to measure safety as the principal measure. Six reportable events from study participants are summarized in Table 2. These events were equally distributed among the study cohorts and none appeared to be due to the SalpIL2 organism.

Table 2.

Reported events by cohort

| Dose cohort | Reported events |

|---|---|

| 1 × 10^5 | None |

| 1 × 10^6 | Gastric dilatation and volvulus |

| 1 × 10^7 |

Staph aureus wound infection Recurrent urinary tract infections |

| 1 × 10^8 |

Beta‐haemolytic streptococcus wound infection Urine crystals |

| 1 × 10^9 |

Enterobacter wound infection Staphylococcus wound infection |

Faecal Salmonella cultures were used to assess shedding of SalpIL2. The organism was not cultured from faeces of any dog during the study period. One dog was positive for a Salmonella sp, which was genetically unrelated to that used to generate the recombinant SalpIL2, and was subsequently determined to be due to contamination of the dog's food.

Chemotherapy‐related adverse events were observed in 17/19 (89%) study dogs (Table 3). These were transient, self‐limiting and consistent with those previously reported. No grade 3 or 4 events were observed. Doxorubicin was reduced to 25 mg/m2 due to grade 2 neutropenia in four study dogs. There were no treatment delays required during the doxorubicin protocol.

Table 3.

Chemotherapy‐related toxicities by grade and cohort

| Dose cohort (Dogs) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse event classification | Grade | 1 × 10^5 (n = 3) | 1 × 10^6 (n = 3) | 1 × 10^7 (n = 3) | 1 × 10^8 (n = 3) | 1 × 10^9 (n = 7) |

| Neutropenia | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Thrombocytopenia | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 2 | 1 | |||||

| Anaemia | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Anorexia | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Diarrhoea | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

Eighteen of the 19 study dogs showed an increase in the total white blood cell count at day 10 before limb amputation Table S3. The total white blood cell count returned to baseline within 3 weeks, during which time all dogs also had a limb amputation. Such an increase in the total white blood cell count was not consistently observed when SalpIL2 was given concurrently with doxorubicin for the rest of the study.

Immediately following amputation, tumours from five dogs were assayed for the presence of SalpIL2. No SalpIL2 colonies were observed on agar plate cultures from any of the tumour tissue homogenates.

Assessment of outcome

Efficacy was a secondary measure based on the phase I design of this study. DFI and OS from this study cohort and from the two comparison groups were used to assess if SalpIL2 altered the outcome expected with amputation and adjuvant chemotherapy.

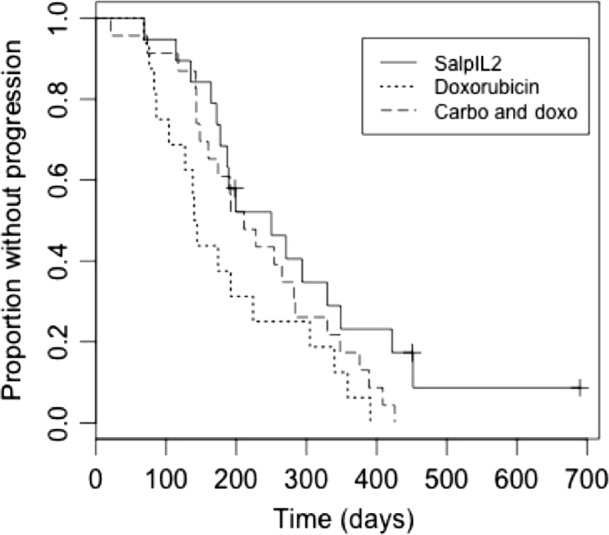

The DFI for the study dogs ranged from 69 days to more than 880 days with a median of 199 days (Fig. 2). Three of the 19 dogs did not develop metastases during the study period. The DFI for the three dogs that had wound infections were 330, 349 and 250 days, which was not different (P = 0.30) from the study dogs.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves plotting disease free interval in dogs with non‐metastatic appendicular osteosarcoma receiving SalpIL2 (solid line), doxorubicin alone (dotted line) or doxorubicin and carboplatin (dashed line). Cross marks represents censored dogs. The disease‐free interval (DFI) for dogs treated with doxorubicin alone was significantly shorter (P = 0.004) than that of the dogs treated with SalpIL2. The DFI for dogs treated with carboplatin and doxorubicin was not a significantly different (P = 0.189) from that of the dogs treated with SalpIL2.

Interestingly, the dogs treated using lower doses of SalpIL2 (cohorts 1–4, combined) had longer DFI than the dogs treated using the highest SalpIL2 dose (cohort 5) (P < 0.01). (Fig. S1). The median DFI for the comparison groups 1 and 2 were 142 days and 211 days, respectively. The DFI for comparison group 1 was significantly shorter (P = 0.004) than that of the dogs treated with SalpIL2. The DFI for comparison group 2 was not a significantly different (P = 0.189) from that of the dogs treated with SalpIL2. In addition, the dogs treated using lower doses of SalpIL2 (cohorts 1–4) also had longer median DFI than the two comparison groups. As noted above, the total white blood cell count was the only laboratory value that was consistently altered (increased) in the dogs treated with SalpIL2. However, there was no correlation between the increased white blood cell counts and the observed DFI.

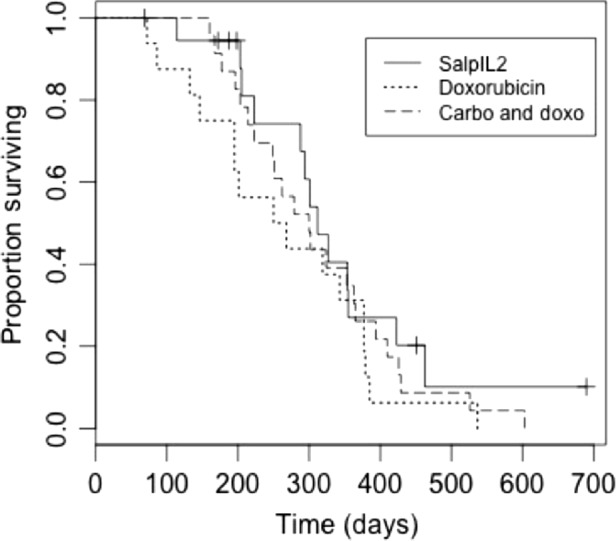

The proportion of dogs that did not develop metastasis at 360 days in the study group (22%, ranging from 422 days to more than 880 days of follow‐up) was significantly different (P = 0.034) than that for the two comparison groups (<10%, ranging from 376 days to 426 days of follow‐up). The median OS for the study dogs was 294 days (Fig. 3) and five dogs (26%) were alive at 360 days. The median OS for the three dogs that had wound infections was 350, 354 and 288 days. The median OS for comparison groups 1 and 2 were 259 days and 300 days, respectively. Ten dogs (25%) in the combined comparison groups were alive at 360 days. The median OS for the study dogs and the dogs in the comparison groups considered alone or in combination was not significantly different.

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier curves plotting overall survival (OS) in dogs with non‐metastatic appendicular osteosarcoma receiving SalpIL2 (solid line), doxorubicin alone (dotted line) or doxorubicin and carboplatin (dashed line). Cross marks represents censored dogs. The median OS for the SalpIL2 dogs and the dogs treated with doxorubicin or doxorubicin and carboplatin considered alone or in combination were not significantly different.

As was true for DFI, the dogs treated using lower doses of SalpIL2 (cohorts 1–4, combined) had significantly longer OS (P = 0.02) than the dogs in cohort 5 treated using the highest SalpIL2 dose (Fig. S2). By the end of the study, 13 dogs had died due to disease progression (metastasis) that precipitated euthanasia and one dog was killed without disease progression due to doxorubicin cardiotoxicity. Metastatic osteosarcoma was confirmed in each of the nine study dogs for which a necropsy was performed.

Discussion

The use of both Salmonella and IL‐2 in cancer has been limited by systemic toxicity (Sorenson et al. 2010; Modiano et al. 2012). Here, we report the results of a prospective, open label, phase I dose‐cohort escalation clinical study evaluating safety of orally administered, genetically engineered S. Typhimurium in combination with amputation and adjuvant doxorubicin in dogs with non‐metastatic appendicular osteosarcoma. The data show that SalpIL2 was safe and well tolerated. We did not observe any toxicity that could be unambiguously attributed to SalpIL2. Furthermore, we detected a preliminary efficacy signal, which supports additional testing to establish the potential for SalpIL2 as a novel form of adjuvant therapy for dogs with appendicular osteosarcoma.

This therapeutic platform includes several novel aspects. First, after oral administration, S. Typhimurium has been shown to invade the intestinal epithelium, colonize in Peyer's patches and enter the lymphatics and bloodstream in humans and mice by infecting macrophage and dendritic cells (Vaupel 2004). Microscopic histopathological analysis of SalpIL2‐treated experimental animals revealed that the intestine, liver and spleen underwent the most changes of all tissues (Morrisse et al. 2010). In addition, oral SalpIL2 administration resulted in sporadic increases in inflammatory cells determined by a complete blood count (Morrisse et al. 2010). Second, attenuated S. Typhimurium strains have a propensity to colonize tumours (Veterinary cooperative oncology group, 2004). In vitro experiments have demonstrated the ability of SalpIL2 to invade and divide favourably within osteosarcoma cells when compared to primary murine hepatocytes (Soto et al. 2004). Thus, SalpIL2 may be able to persist for long periods in malignant tissues providing prolonged antigen presentation and enhanced immune response in tumours. In previous experiments, female Balb/c mice were administered murine osteosarcoma cells by tail vein injection (Selmic et al. 2014). Three days later, the mice were orally gavaged with SalpIL2 and killed on day 21 for tumour enumeration, volume and assessment of lymphocyte populations. SalpIL2 reduced the overall volume and mean number of metastatic nodules with respect to saline controls. Histological analysis of the metastatic tissues in mice treated with SalpIL2 showed an increased invasion of mononuclear cells into the tissue. Furthermore, splenic NK cell populations increased in SalpIL2‐treated mice compared to the saline controls. Third, intravenous administration of Salmonella sp has been associated with severe and life‐threatening adverse events in humans and dogs, including thrombocytopenia, anaemia, persistent bacteraemia, hyperbilirubinemia, diarrhoea, vomiting, nausea, elevated alkaline phosphatase, hypophosphatemia and treatment‐related death in one dog (Sorenson et al. 2008b, 2010). An inherent safety concern is apparent with intravenous administration of bacterial‐based cancer therapies to dogs with cancer, as evidenced by the observation that a trial using Clostridium‐novyi spores was discontinued due to dose‐limiting toxicities (Watson & Holden 2010). In contrast, administration of attenuated SalpIL2 by the oral route avoids these adverse effects (Schwartz et al. 2002; Soto et al. 2003; Phillips et al. 2009; Morrisse et al. 2010).

Our study was primarily designed to measure the safety of oral SalpIL2 in a realistic clinical setting. Oral administration of SalpIL2 did not create detectable systemic toxicity. None of the six reportable events in the study dogs were obviously attributable to the SalpIL2; therefore, we conclude this therapy was well tolerated. Also, the absence of dose‐limiting toxicity allowed us to expand the last study cohort to include four additional dogs. SalpIL2 was not cultured from faeces of any dog during the study period. This could be due to efficient small intestinal absorption of SalpIL2 or the biological mass of SalpIL2, relative to normal flora, was under the threshold of detection using routine anaerobic cultures. We cannot completely exclude the possibility that SalpIL2 failed to survive passage through the gastrointestinal system, but we favour one of the first two alternatives. The data suggest that SalpIL2 was biologically active as determined by the presence of an increased in the total white blood cell (lymphocytosis and monocytosis) count at day 10 in 18/19 study dogs. The total white blood cell count returned to baseline within 3 weeks in each of these dogs. The presence of an inflammatory leukogram supports a biologically response to the SalpIL2, but we cannot prove successful colonization. These observations are consistent with previous data in mice, where oral SalpIL2‐induced peripheral inflammatory responses in mice as determined by splenic lymphocytosis (elevated numbers of cytotoxic T cells and NK cells) that returned to normal within 4 weeks after administration (Selmic et al. 2014). No prolonged alterations in the peripheral leukogram were observed in the study dogs. However, this could be attributable to the concurrent administration of SalpIL2 with chemotherapy, so the peak leukocytosis associated with SalpIL2 might have coincided with the leukopoenic nadir induced by chemotherapy, resulting in attenuated peripheral inflammation.

Efficacy was a secondary measure in this study. Limitations of this study were those inherent to using retrospective, historical comparison groups. The increased DFI observed in the study dogs vs. comparison group 1 that received the same chemotherapy protocol suggests that a further investigation of efficacy of SalpIL2 is warranted. Interestingly, comparison group 1, which was treated with doxorubicin alone, had the shortest DFI and did worse than what has been previously reported. Comparison group 2, which was treated with alternating doxorubicin and carboplatin, showed prolonged DFI vs. dogs treated with doxorubicin alone. A benefit of this combination has not been reproducibly reported by other groups (Whittington & Faulds 1993; Coburn et al. 2007; Fenger et al. 2014). The DFI in the study group was comparable to that of comparison group 2.

The median OS for the study dogs was not significantly different than that observed in the two comparison groups, and this was not due to the variable use of rescue therapies. Interestingly, study dogs treated using lower doses of SalpIL2 had longer OS than the dogs treated using the highest dose of SalpIL2. We are unclear why our study dogs treated at lower doses had longer DFI and OS, but the biologically active dose in biological therapies is often not the same as the therapeutic dose. This is counterintuitive because low doses of IL‐2 might provide greater stimulation for regulatory T cells (Tregs), whereas higher doses should lead to activation of effector cells and eosinophilia (Krick et al. 2012; Bell et al. 2015). This phase I trial successfully showed that SalpIL2 was safe, and the potential efficacy signal allows us to generate testable hypotheses to design future studies, using one of the first four doses of SalpIL2.

The lack of Salmonella growth from the tumours after amputation suggests that any possible advantage of the SalpIL2 group must have been secondary to a systemic immunologic effect rather than direct tumour targeting that Salmonella is supposed to engender. Therefore, we are working to identify methods of conditioning tumours to be more readily colonized by administered bacteria (Drees, et al., ”Vasculature Disruption Enhances Bacterial Targeting of Autochthonous Tumors,” manuscript submitted). Assessment of a primary outcome measure assessing infection (e.g. culture of SalpIL‐2) from amputated tissue or tissue IL‐2 assays would be a valuable outcome measure in similar studies conducted in the future.

Currently, there is no consensus among veterinarians as to the optimal chemotherapy protocol for dogs with appendicular osteosarcoma (Dow et al. 2005; Coburn et al. 2007; Crull et al. 2011; Ehrhart et al. 2013; Fenger et al. 2014). Our data indicate that SalpIL2 in combination with amputation and adjuvant doxorubicin is safe and well tolerated, and it might provide clinical benefit for dogs with non‐metastatic appendicular osteosarcoma.

Source of funding

This study was supported in part by a grant from the Minnesota Medical Foundation (to DS) and by the Children's Cancer Research Fund. JFM is supported in part by the Alvin S. and June Perlman Chair in Animal Oncology at the University of Minnesota.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: EG, AW, KS, VW, LA, JM, DS; Performed the experiments: SF, MH, AW, KS, AB; Analyzed the data: SF, UY, JM, DS; Wrote the paper: SF, JM, DS.

Supporting information

Fig S1. Dot plot diagram of the disease free interval for the five SalpIL2 treatment cohorts. The dogs treated using lower doses of SalpIL2 (cohorts 1–4) had longer disease free intervals than the dogs treated using the highest SalpIL2 dose (cohort 5).

Fig S2. Dot plot diagram of the overall survival for the five SalpIL2 treatment cohorts. The dogs treated using lower doses (cohorts 1–4) of SalpIL2 had longer overall survivals than the dogs treated using the highest (cohort 5) SalpIL2 dose.

Table S1. Trial design.

Table S2. Additional study patient information.

Table S3. Total white blood cell counts (count/ul) throughout study period.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the nursing and technical staff of the Oncology and Surgery Services of the VMC, University of Minnesota for assistance with clinical management of the dogs in this study, Dr. Roy Katz at CustomRx Compounding Pharmacy for assistance compounding SalpIL2, and Drs. Brenda Weigel and Denis Clohisy for assistance with study development and implementation. This study was supported in part by a grant from the Minnesota Medical Foundation (to DS) and by the Children's Cancer Research Fund. The authors gratefully acknowledge donations to the Animal Cancer Care and Research Program of the University of Minnesota that helped support this project. JFM is supported in part by the Alvin S. and June Perlman Chair in Animal Oncology at the University of Minnesota.

References

- Bailey D., Erb H., Williams L., Ruslander D., Hauck M. (2003) Carboplatin and doxorubicin combination chemotherapy for the treatment of appendicular osteosarcoma in the dog. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 17, 199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell C.J., Sun Y., Nowak U.M., Clark J., Howlett S., Pekalski M.L. et al (2015) Sustained in vivo signaling by long‐lived IL‐2 induces prolonged increases of regulatory T cells. Journal of Autoimmunity 56, 66–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg J., Weinstein M.J., Springfield D.S. et al (1995) Results of surgery and doxorubicin chemotherapy in dogs with osteosarcoma. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 206, 1555–1560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coburn B., Grassl G.A. & Finlay B.B. (2007) Salmonella, the host and disease: a brief review. Immunology and Cell Biology 85, 112–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crull K., Bumann D. & Weiss S. (2011) Influence of infection route and virulence factors on colonization of solid tumors by Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium . FEMS Immunology and Medical Microbiology 62, 75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dow S., Elmslie R., Kurzman I., MacEwen G., Pericle F. & Liggitt D. (2005) Phase I study of liposome‐DNA complexes encoding the interleukin‐2 gene in dogs with osteosarcoma lung metastasis. Human Gene Therapy 16, 937–946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrhart NP., Ryan S.D., Fan T.M. (2013) Tumors of the skeletal system In: Withrow & MacEwen's Small Animal Clinical Oncology. 5th ed. pp 463–503. Elsevier: St. Louis. [Google Scholar]

- Fenger J.M., London C.A. & Kisseberth W.C. (2014) Canine osteosarcoma: a naturally occurring disease to inform pediatric oncology. Institute for Laboratory Animal Research Journal 55, 69–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco O., Marples B., Joiner M.C. & Scott S.D. (2003) How to overcome (and exploit) tumor hypoxia for targeted gene therapy. Journal of Cellular Physiology 197, 312–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haagsman A.N., Witkamp A.J., Sjollema B.E., Kik M.J. & Kirpensteijn J. (2013) The effect of interleukin‐2 on canine peripheral nerve sheath tumours after marginal surgical excision: a double‐blind randomized study. BMC Veterinary Research 9, 155–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfand S.C., Modiano J.F. & Nowell P.C. (1992) Immunophysiological studies of interleukin‐2 and canine lymphocytes. Veterinary Immunology Immunopathology. 33, 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfand S.C., Soergel S.A., Modiano J.F., Hank J.A. & Sondel P.M. (1994a) Induction of lymphokine‐activated killer (LAK) activity in canine lymphocytes with low dose human recombinant interleukin‐2 in vitro. Cancer Biotherapy and Radiopharmaceuticals 9, 237–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfand S.C., Soergel S.A., MacWilliams P.S., Hank J.A. & Sondel P.M. (1994b) Clinical and immunological effects of human recombinant interleukin‐2 given by repetitive weekly infusion to normal dogs. Cancer Immunology Immunopathology 39, 84–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia L., Wei D.P., Sun Q.M., Jin G.H., Li S.F., Huang Y. & Hua Z.C. (2007) Tumor‐targeting Salmonella typhimurium improves cyclophosphamide chemotherapy at maximum tolerated dose and low dose metronomic regimens in a murine melanoma model. International Journal of Cancer 121, 666–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krick E.L., Sorenmo K.U., Rankin S.C., Cheong I., Kobnn S. & Diaz L.A. (2012) Evaluation of clostridium novyi‐NT spores in dogs with naturally occurring tumors. American Journal of Veterinary Research 73, 112–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane A.E., Black M.L. & Wyatt K.M. (2012) Toxicity and efficacy of a novel doxorubicin and carboplatin chemotherapy protocol for the treatment of canine appendicular osteosarcoma following limb amputation. Australian Veterinary Journal 90, 69–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao W., Lin J.X. & Leonard W.J. (2013) Interleukin‐2 at the crossroads of effector responses, tolerance, and immunotherapy. Immunity 38, 13–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mengesha A., Dubois L., Lambin P., Landuyt W., Chiu J.K., Wouters B.G. & Thays J. (2006) Development of a flexible and potent hypoxiainducible promoter for tumor‐targeted gene expression in attenuated salmonella. Cancer Biology and Therapy 5, 1120–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modiano J.F., Bellgrau D., Cutter G.R., Lana S.E., Ehrhart E., Wilke V.L. et al (2012) Inflammation, apoptosis, and necrosis induced by neoadjuvant fas ligand gene therapy improves survival in dogs with spontaneous bone cancer. Molecular Therapy 20, 2234–2243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrisse D., O'Sullivan G.C. & Tangney M. (2010) Tumour targeting with systemically administered bacteria. Gene Therapy 10, 3–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patyar S., Joshi R., Byrav D.S., Prakash A., Medhi B. & Das B.K. (2010) Bacteria in cancer therapy: a novel experimental strategy. Journal of Biomedical Science 23, 17–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips B., Powers B.E., Dernell W.S., Straw R.C., Khanna C., Hogge G.S. & Vail D.M. (2009) Use of single agent carboplatin as adjuvant or neoadjuvant therapy in conjunction with amputation for appendicular osteosarcoma in dogs. Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association 45, 33–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg S.A. (2014) IL‐2: the first effective immunotherapy for human cancer. Journal of Immunology 192, 5451–5458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saltzman D.A., Heise C.P., Hasz D.E., Zebede M., Kelly S.M., Curtiss R. III et al (1996) Attenuated Salmonella typhimurium containing interleukin‐2 decreases MC‐38 hepatic metastases: a novel anti‐tumor agent. Cancer Biotherapy Radiopharmaceuticals 11, 145–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saltzman D.A., Katsanis E., Heise C.P., Hasz D.E., Vigdorovich V., Kelly S.M. et al (1997a) Antitumor mechanisms of attenuated Salmonella typhimurium containing the gene for human interleukin‐2: a novel antitumor agent? Journal of Pediatric Surgery 32, 301–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saltzman D.A., Katsanis E., Heise C.P., Hasz D.E., Kelly S.M., Curtiss R. III et al (1997b) Patterns of hepatic and splenic colonization by an attenuated strain of Salmonella typhimurium containing the gene for human interleukin‐2: a novel anti‐tumor agent. Cancer Biotherapy Radiopharmaceuticals 12, 37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schodel F., Kelly S.M., Peterson D.L., Milich D.R. & Curtiss R. III (1994) Hybrid hepatitis B virus core‐pre‐S proteins synthesized in avirulent Salmonella typhi‐murium and Salmonella typhi for oral vaccination. Infection and Immunity 62, 1669–1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz R.N., Stover L. & Dutcher J. (2002) Managing toxicities of high‐dose interleukin‐2. Oncology (Williston Park) 16, 11–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selmic L.E., Burton J.H., Thamm D.H., Withrow S.J. & Lana S.E. (2014) Comparison of carboplatin and doxorubicin‐based chemotherapy protocols in 470 dogs after amputation for treatment of appendicular osteosarcoma. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 28, 554–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim G.C. & Radvanyi L. (2014) The IL‐2 cytokine family in cancer immunotherapy. Cytokine Growth Factor Reviews 25, 377–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skorupski K.A., Uhl J.M., Szivek A., Frazier S.D., Rebhum R.B., Rodriguez C.O. Jr (2016) Carboplatin versus alternating carboplatin and doxorubicin for the adjuvant treatment of canine appendicular osteosarcoma: a randomized, phase III trial. Veterinary & Comparative Oncology 14, 81–87doi: 10.1111/vco.12069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorenson B.S., Banton K.L., Frykman N.L., Leonard A.S. & Saltzman D.A. (2008a) Attenuated Salmonella typhimurium with IL‐2 gene reduces pulmonary metastases in murine osteosarcoma. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 466, 1285–1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorenson B.S., Banton K.L., Frykman N.L., Leonard A.S. & Saltzman D.A. (2008b) Attenuated Salmonella typhimurium with interleukin 2 gene prevents the establishment of pulmonary metastases in a model of osteosarcoma. Journal of Pediatric Surgery 43, 1153–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorenson B., Banton K., Augustin L., Barnett S., McCulloch K., Dorn J. et al (2010) Safety and immunogenicity of Salmonella typhimurium expressing C‐terminal truncated human IL‐2 in a murine model. Biologics 4, 61–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto L.J., Sorenson B.S., Kim A.S., Feltis B.A., Leonard A.S. & Saltzman D.A. (2003) Attenuated Salmonella typhimurium prevents the establishment of unresectable hepatic metastases and improves survival in a murine model. Journal of Pediatric Surgery 38, 1075–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto L.J. III, Sorenson B.S., Nelson B.W., Solis S.J., Leonard A.S., Saltzman D.A. (2004) Preferential proliferation of attenuated Salmonella typhimurium within neuroblastoma. Journal of Pediatric Surgery 39, 937–940; discussion ‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spodnick G.J., Berg J., Rand W.M., Schelling S.H., Couto G., Harvey H.J. et al (1992) Prognosis for dogs with appendicular osteosarcoma treated by amputation alone: 162 cases (1978‐1988). Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 200, 995–999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straw R.C., Withrow S.J. & Powers B.E.(1990) Management of canine appendicular osteosarcoma. Veterinary Clinics of North America Small Animal Practice 20, 1141–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thamm D.H., Kurzman I.D., King I., Li Z., Sznol M., Dubielzis R.R. et al (2005) Systemic administration of an attenuated, tumor targeting Salmonella typhimurium to dogs with spontaneous neoplasia: phase I evaluation. Clinical Cancer Research 11, 4827–4834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toso J.F., Gill V.J., Hwu P., Marincola F.M., Reslifo N.P., Schwartzentruber D.J. et al (2002) Phase I study of the intravenous administration of attenuated Salmonella typhimurium to patients with metastatic melanoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology 20, 142–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaupel P. (2004) The role of hypoxia‐induced factors in tumor progression. Oncologist 9, 10–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veterinary cooperative oncology group (2004) Veterinary cooperative oncology group ‐ common terminology criteria for adverse events (VCDOG‐CTCAE) following chemotherapy or biological antineoplastic therapy in dogs and cats v1.0. Veterinary and Comparative Oncology 2, 195–2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson K.G. & Holden D.W. (2010) Dynamics of growth and dissemination of Salmonella in vivo . Cellular Microbiology 12, 1389–1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittington R. & Faulds D. (1993) Interleukin‐2: a review of its pharmacologic properties and therapeutic use in patients with cancer. Drugs 46, 446–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig S1. Dot plot diagram of the disease free interval for the five SalpIL2 treatment cohorts. The dogs treated using lower doses of SalpIL2 (cohorts 1–4) had longer disease free intervals than the dogs treated using the highest SalpIL2 dose (cohort 5).

Fig S2. Dot plot diagram of the overall survival for the five SalpIL2 treatment cohorts. The dogs treated using lower doses (cohorts 1–4) of SalpIL2 had longer overall survivals than the dogs treated using the highest (cohort 5) SalpIL2 dose.

Table S1. Trial design.

Table S2. Additional study patient information.

Table S3. Total white blood cell counts (count/ul) throughout study period.