Abstract

Objective

To evaluate practice variations amongst neonatologists regarding oxygen management in neonates with persistent pulmonary hypertension of newborn (PPHN).

Study Design

An online survey was administered to neonatologists to assess goal oxygenation targets and oxygen titration practices in PPHN. Response variations were assessed and intergroup comparisons performed.

Results

Thirty-three percent (492) of neonatologists completed the survey. Twenty-eight percent reported using specific oxygen titration guidelines. Majority of respondents used a combination of oxygen saturation (SpO2) and arterial oxygen tension (PaO2) initially to titrate oxygen. Seventy percent of the respondents used higher goal SpO2 > 95% or 95 to 98% and thirty-eight percent of the respondents used PaO2 > 80 mm Hg. Physicians with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation experience and those with greater than ten years neonatal intensive care unit experience inclined toward use of SpO2 alone for oxygen titration and aimed for lower range of SpO2 and PaO2 targets. Greater proportion of neonatologists who employed specific oxygen titration guidelines used lower SpO2 targets.

Conclusion

Wide practice variations exist amongst neonatologists regarding optimal SpO2 and PaO2 targets and oxygen titration practices in the management of PPHN.

Keywords: persistent pulmonary hypertension of newborn, oxygen targets, survey, practice variations

Persistent pulmonary hypertension in newborn (PPHN) is a syndrome in the newborn period that is estimated to occur in approximately 1.9 per 1,000 live births and significantly increases the risk of mortality and morbidity.1–4 It is characterized by failure of the rapid fall in pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) that normally occurs during cardiopulmonary transition at birth. Of the multiple mechanisms that play a critical role in the normal cardiopulmonary transition process, postnatal increase in oxygen tension in the lung is one of the key factors that promote pulmonary vasorelaxation. Supplemental oxygen is therefore the most common therapy used in the management of PPHN.4 Neonatologists have traditionally used high concentrations of inspired oxygen (FiO2) to treat infants with suspected or confirmed PPHN and aim toward achieving high arterial oxygen tension (PaO2) and oxygen saturation (SpO2). However, recent preclinical evidence suggests that hyperoxia is deleterious and in fact may worsen PVR by inhibiting natural mediators that maintain pulmonary vasorelaxation.5,6 While multiple large randomized controlled trials have been performed in preterm infants to identify optimal SpO2 targets, there is paucity of evidence in near-term and term infants with PPHN to guide optimal oxygenation targets that will maximize pulmonary vasodilatation without significantly inducing deleterious effects of hyperoxia.7–9 Additionally, current physician perceptions regarding optimal SpO2 and PaO2 targets and titration of FiO2 in infants with PPHN are unknown. We hypothesized that wide practice variations will exist amongst neonatologists regarding use and titration of supplemental oxygen for management of PPHN. The objective of this study is to survey neonatologists regarding their practice styles and perceptions of optimal use of supplemental oxygen in the treatment of PPHN and identify areas of practice variations. Results of this survey would inform gaps in current knowledge regarding use of oxygen and optimal oxygenation targets in infants with PPHN that can serve as potential areas for future research to delineate evidence-based guidelines. Optimal oxygen exposure may further improve outcomes of infants with PPHN.

Methods

A prospective cross-sectional quantitative survey consisting of 9 multiple choice questions was designed using an online survey tool as shown in Table 1. Respondents were allowed to pick one answer. The survey consisted of questions related to clinical practices regarding criteria used for titration of FiO2 and demographic questions related to neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) level, experience with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), and overall experience as neonatologists. The questionnaire was distributed electronically between March 2015 and January 2016, with three reminders in between. Neonatologists were identified from Section of Perinatal Pediatrics of American Academy of Pediatrics. Participation in the survey was voluntary and the respondents’ identity was kept confidential throughout. The protocol was exempted from full review by the local institutional review board.

Table 1.

Survey questionnaire

| 1. How do you titrate O2 in the initial treatment of neonatal PPHN? |

| a) I maintain the infant on 100% O2 until I’m confident that the pulmonary vascular reactivity has stabilized. Until then, I do not wean O2 even if infant’s SpO2 is 100% and PaO2 is > 100 mm Hg |

| b) I wean based on SpO2 |

| c) I wean based on PaO2 |

| d) I use a combination of SpO2 and PaO2 |

| 2. What goal parameters of preductal O2 saturation (SpO2) do you use during treatment of pulmonary hypertension of newborn? |

| a) > 95% |

| b) 92–96% |

| c) 95–98% |

| d) 92–98% |

| 3. What goal PaO2 parameters do you use to wean FiO2 in PPHN? |

| a) I do not use PaO2 for oxygen weaning purposes |

| b) > 120 mm Hg |

| c) 60–100 mm Hg |

| d) 80–120 mm Hg |

| 4. If you are asked to wean FiO2 based on preductal SpO2 and there is no significant difference between pre and postductal O2 saturation, how frequently would you wean? |

| a) Wean O2 by 2% every 1 h if O2 saturation greater than goal |

| b) Wean O2 by 2% every 30 min if O2 saturation greater than goal |

| c) Wean O2 by 2% every 15 min if O2 saturation greater than goal |

| d) Wean O2 by 2% every 5 min if O2 saturation greater than goal |

| 5. Do you use a specific protocol or clinical practice guideline that the nurses or respiratory therapists use to titrate FiO2 for infants with PPHN in your NICU? |

| a) Yes |

| b) No |

| 6. How long have you been practicing neonatology? |

| a) < 5 y |

| b) 5–10 y |

| c) 10–20 y |

| d) >20y |

| 7. Do you manage infants on ECMO? |

| a) Yes |

| b) No |

| 8. How long have you been an ECMO physician? |

| a) < 5 y |

| b) 5–10 y |

| c) 10–20 y |

| d) > 20 y |

| e) I do not manage ECMO patients. |

| 9. The NICU I work-in, is best described as: |

| a) Level-3 NICU |

| b) Level-4 NICU with low ECMO volume (<15 neonatal ECMO runs a year) |

| c) Level-4 NICU with high ECMO volume (>15 neonatal ECMO runs a year) |

Abbreviations: ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; FiO2, inspired oxygen; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit; PaO2, arterial oxygen tension, PPHN, persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn; SpO2, oxygen saturation.

We asked whether neonatologists preferred to use SpO2, PaO2, or both to titrate FiO2 and their preferred target ranges of SpO2 and PaO2. In addition, we surveyed the rate at which neonatologists would wean FiO2 if SpO2 target was achieved. Finally, we asked if standard guidelines or protocols were used for weaning FiO2.

The responses to individual questions were summarized by counts and percentages and used to determine practice variability. Comparisons were made between neonatologists with and without ECMO experience, with less than or greater than ten years of NICU experience, and between those who used guidelines for titration of FiO2 and those who didn’t. Chi square test or Fisher exact test was used for analysis and level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

The survey was sent to 1,500 neonatologists and a total of 492 neonatologists completed the survey. The response rate was 33% (492/1,500).

Demographics

A total of 36% (176/492) of all respondents managed neonates on ECMO. In all, 69% (340/492) of the respondents had more than ten years of experience as a neonatologist and of those 74% (252/340) had greater than twenty years of experience. Equal proportion of physicians worked in level 3 and 4 NICU. A total of 72% of all respondents who worked in level 4 NICU managed neonates on ECMO (175/244). Majority of the respondents with ECMO experience worked in low volume ECMO centers considered as less than 15 neonatal ECMO runs per year.10

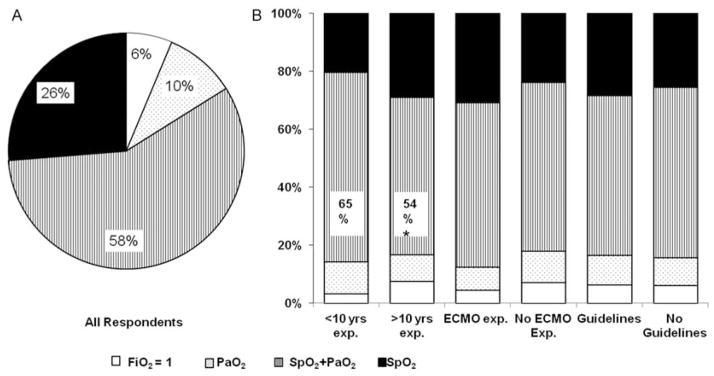

Initial Oxygen Titration Parameters

First we asked whether neonatologists used SpO2, PaO2, a combination of SpO2 and PaO2, or neither for titration of FiO2 during the initial management of PPHN. As shown in Fig. 1A, majority of respondents used a combination of SpO2 and PaO2 (58%; 283/492) followed by SpO2 alone (26%; 129/492). A total of 10% of all respondents used PaO2 alone and 6% of respondents preferred to treat with FiO2 of 1.0 until they were confident that the pulmonary vascular reactivity had stabilized and did not wean FiO2 even if infant’s SpO2 is 100% and PaO2 is greater than 100 mmHg. Respondents with less than ten years of NICU experience used a combination of SpO2 and PaO2 for initial oxygen titration more often compared with respondents with greater than ten years NICU experience (<10 years NICU experience vs >10 years NICU experience; 65% [99/152] vs 54% [184/340]; p = 0.02) (Fig. 1B). There was a trend toward use of SpO2 alone for initial oxygen titration among respondents with greater than ten years NICU experience (<10 years NICU experience vs >10 years NICU experience; 20% [31/152] vs 29% [(98/340]; p = 0.05) (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Initial oxygen titration parameters. (a) Percentage distribution of goal oxygenation parameters used for oxygen titration in initial persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn management for all responders. (b) Comparison of use of oxygenation parameters between neonatologists with or without greater than ten years of neonatal intensive care unit experience, with or without extracorporeal membrane oxygenation experience, and with or without use of specific O2 titration guidelines. Note: *p < 0.05.

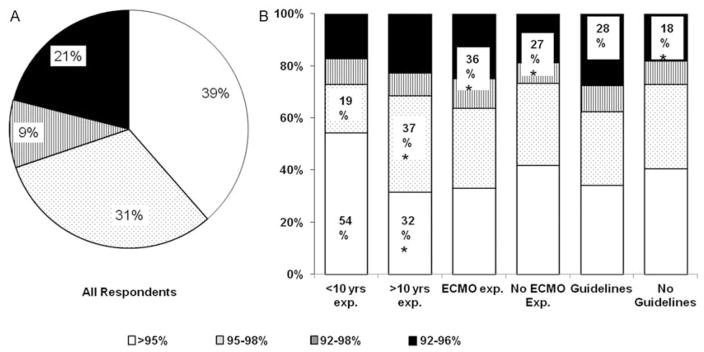

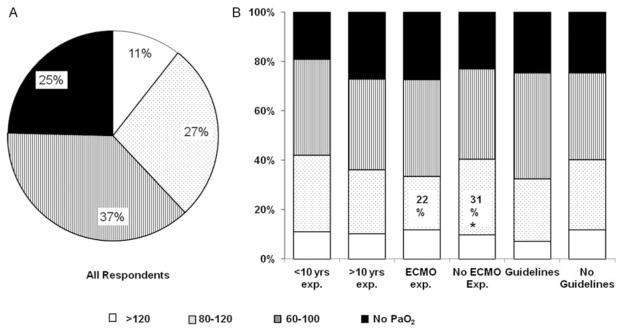

Target Oxygen Saturation and Arterial Oxygen Tension Ranges

We next evaluated practice variations in the target ranges of preductal SpO2 and PaO2 used to titrate FiO2 in infants with PPHN. A total of 70% of all respondents chose to target higher ranges of SpO2 of greater than 95% or 95 to 98%, whereas, 30% of all respondents used lower SpO2 target ranges of 92 to 96% or 92 to 98%. In all, 39% (189/492) of all respondents aimed for goal preductal SpO2 greater than 95% and did not use an upper limit to target SpO2 (Fig. 2A). As for PaO2, 37% (184/492) of all respondents aimed to achieve target PaO2 of 60 to 100 mmHg and 38% (187/492) of respondents choose to maintain PaO2 greater than 80 mmHg. While 25% (121/492) of physicians did not use PaO2 for oxygen titration after initial stabilization, 11% (52/492) of respondents chose to target PaO2 greater than 120 mm Hg (Fig. 3A). In summary, wide variations were noted amongst neonatologists with respect to the target ranges of SpO2 and PaO2 used for management of PPHN.

Fig. 2.

Target preductal peripheral capillary oxygen saturation (SpO2) ranges for persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN) management. (a) Percentage distribution of target ranges of SpO2 used for PPHN management for all responders. (b) Comparison of target ranges of SpO2 used by neonatologists with or without greater than ten years of neonatal intensive care unit experience, with or without extracorporeal membrane oxygenation experience and with or without use of specific O2 titration guidelines. Note: *p < 0.05.

Fig. 3.

Target partial pressure arterial oxygen (PaO2) ranges for persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN) management. (a) Percentage distribution of target ranges of PaO2 used for PPHN management for all responders. (b) Comparison of target ranges of PaO2 used by neonatologists with or without greater than ten years of neonatal intensive care unit experience, with or without extracorporeal membrane oxygenation experience, and with or without use of specific O2 titration guidelines. Note: *p < 0.05.

When compared based on ECMO experience, 22% (38/176) of neonatologists with ECMO experience used PaO2 80 to 120 mm Hg compared with 31% (97/316) neonatologists without ECMO experience (p = 0.03; (Fig. 3B). ECMO experienced physicians aimed for lower SpO2 target of 92 to 96% or 92 to 98% compared with non-ECMO experienced physicians (ECMO vs non-ECMO, 36% [64/176] vs 27% [84/316]; p = 0.02; Fig. 2B). Greater proportion of neonatologists with ECMO experience did not use PaO2 for FiO2 titration (ECMO vs non-ECMO, 27% [48/176] vs 23% [73/316]) as shown in Fig. 3B, although the difference was not statistically significant.

Furthermore, neonatologists with greater than 10 years of NICU experience, more frequently used 95 to 98% as SpO2 target (37% [125/340] vs 19% [28/152]; p < 0.0001) and less frequently used > 95% as SpO2 target when compared with neonatologists with less than 10 years NICU experience (32% [107/340] vs 54% [82/152]; p < 0.0001; Fig. 2B). More experienced physicians did not use PaO2 for target oxygenation compared with less experienced physicians (> 10 years NICU experience vs < 10 years NICU experience; 27% [92/340] vs 19% [29/152]; p = 0.06) (Fig. 3B).

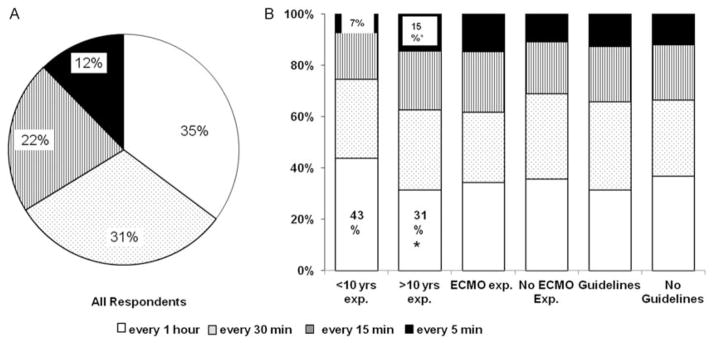

Subsequent Weaning of Oxygen

Since sudden hypoxemic episodes worsen PVR, slow wean of FiO2 to avoid hyperoxia–hypoxemia fluctuations, is one of key components of PPHN management. We therefore sought to examine the rate at which neonatologists would wean FiO2 if infant’s SpO2 was greater than the target range. As shown in Fig. 4A, majority of neonatologists (66%; 318/492) weaned FiO2 by 2% every thirty minutes or one hour. A total of 22% (103/492) of respondents weaned FiO2 by 2% every 15 minutes and 12% (59/492) weaned FiO2 by 2% every 5 minutes. Neonatologists with more than ten years NICU experience weaned FiO2 quicker compared with less experienced neonatologists. Whereas, 43% (65/152) of neonatologists with less than 10 years NICU experience weaned FiO2 by 2% every 1 hour, only 31% (104/340) of neonatologists with greater than 10 years NICU experience weaned at that rate (p = 0.01). In contrast, 15% (48/340) of neonatologists with greater than 10 years NICU experience weaned FiO2 by 2% every 5 minutes compared with only 7% (11/152) of those with less than 10 years NICU experience (p = 0.03). No significant differences were observed in oxygen weaning practices amongst neonatologists based on ECMO experience (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Subsequent oxygen weaning practices. (a) Percentage distribution of oxygen weaning practices for all responders. (b) Comparison of FiO2 weaning practices amongst neonatologists with or without greater than ten years of neonatal intensive care unit experience, with or without extracorporeal membrane oxygenation experience, and with or without use of specific O2 titration guidelines. Note: *p < 0.05.

Oxygen Titration Guidelines

Lastly, we questioned whether specific nurse and/or respiratory therapist driven protocol or clinical practice guideline was used to titrate FiO2 for infants with PPHN in their unit. In all, 28% (138/492) of neonatologists reported the use of specific guidelines. Greater proportion of neonatologists who employed oxygen titration guidelines used lower SpO2 target range of 92 to 96% (guidelines used vs guidelines not used; 28% [38/138] vs 18% [64/353]; p = 0.02) (Fig. 2B). There were no significant differences between the groups with respect to PaO2 ranges and the rate at which FiO2 was weaned.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that wide practice variations exist amongst neonatologists with respect to the use of supplemental oxygen in PPHN management. There is a lack of consensus of the appropriate parameters, SpO2 versus PaO2 and their target ranges, to guide titration of FiO2. The survey also reveals that majority of NICUs do not use specific guidelines or protocols for FiO2 titration to standardize treatment. These variations in practice reflect a lack of evidence to support one strategy over other.

PPHN is a syndrome in the newborn period that contributes substantially to neonatal mortality and morbidity.2,3,11,12 While the underlying etiology and degree of hypoxemia are the most important determinants of the incidence and severity of long-term morbidities, some of the therapies used for PPHN treatment and variations in practice amongst centers may also be a contributing factor. Previous studies reported significant practice variations with respect to best perceived techniques to improve oxygenation, timing of initiation of inhaled nitric oxide, use of surfactant, and type of vasopressor used.13,14 In this study, we specifically examined practice variations in the use of supplemental oxygen which is the most common therapy used for treatment of PPHN and oxidative stress is known to contribute to long-term morbidities.

Both hypoxemia and hyperoxia worsen PVR and an optimal range of SpO2 and PaO2 exists to maintain the least PVR while avoiding hyperoxia-induced lung injury as shown in a lamb model of PPHN and in a small group of infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia and pulmonary hypertension, who underwent cardiac catheterization.6,15 Whether similar results will be observed in neonates with acute PPHN is unknown. As a reflection of lack of adequate evidence in this topic, significant variations in practice were noted in our survey where two-thirds of respondents preferred to use higher SpO2 targets of greater than 95% or 95 to 98% and remaining one-third used lower SpO2 targets of 92 to 96% or 92to 98%. More than one-third of respondents did not use an upper limit of SpO2 target. Majority of respondents also used PaO2 to titrate FiO2, and amongst them almost half chose to target PaO2 greater than 80 mm Hg. This indicates that majority of neonatologists were vigilant toward avoiding hypoxemia but were tolerant to hyperoxia. It is interesting to note that a small proportion of neonatologists (6%) preferred to use 100% oxygen for a prolonged period of time regardless of the infant’s actual oxygenation status until they were confident that the pulmonary vascular reactivity stabilized clinically. The strategy to use 100% oxygen which was commonly used in the past, has become less popular in the recent years due to emerging evidence that high FiO2 exposure induces substantial oxidative stress, alters responses to endogenous and exogenous pulmonary vasodilators, and alters mechanisms that induce vasoconstriction or prevent vasorelaxation.6,16–18

Using a simple online survey, we were able to specifically evaluate the FiO2 weaning practices in the setting of acute PPHN. Two-thirds of the physicians selected a cautious strategy of weaning FiO2 by 2% every 30 minutes or 1 hour if infant’s SpO2 was greater than the target range. The reasons for the same were not collected as part of the survey and we speculate that it may be due to a theoretical concern for rebound increase in PVR with lower levels or rapid fluctuation in oxygenation status. Such a slow rate of wean of oxygen may result in excess proportion of time spent above goal parameters and exposure to detrimental effects of hyperoxia. There is no published data validating appropriate oxygen weaning strategies and further research is needed to test the detrimental effects of hyperoxia or risk of rebound pulmonary vasoconstriction with different weaning strategies.

Physicians working in units with specific oxygen titration guidelines or protocols aimed for lower SpO2 and PaO2 targets when compared with units without specific guidelines. Importantly, only about a quarter of them used standard guidelines for oxygen titration. Use of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines has been shown to reduce practice variations and improve outcomes.19–22 Use of standard protocols for oxygen titration in infants with PPHN may decrease hypoxemia–hyperoxia fluctuations and cumulative oxygen exposure. Appropriate use of oxygen targets may also potentially reduce exposure to other supportive PPHN therapies and thereby potentially improve outcomes while reducing overall cost.

We focused on neonatologist members of the Section of Perinatal Pediatrics of American Academy of Pediatrics and we believe the results can be generalized. The survey cohort is a mixed representation of inborn and out born centers as well as academic and nonacademic centers throughout the United States with variable level of experience in neonatology and ECMO. A response rate of 33% is as good as one can usually get from an internet-based survey, however, it may not be the best representative sample. Response bias has been reported to be less of a concern for physician surveys compared with general population surveys.23

Our study has some limitations. The responses reflect the responders’ perception and it does not always translate into what is actually performed at the bedside. Second, we used certain specific ranges of SpO2 and PaO2 targets and FiO2 weaning frequency in the survey that are most commonly used in clinical practice, and did not include open-ended choices. The response choices are therefore overlapping and the respondents may have felt limited by the choices offered. Nevertheless, this study provides important information about the significant variation in oxygen titration practices for PPHN management in the neonate.

Conclusion

Supplemental oxygen is one of the mainstays of PPHN treatment which is associated with high mortality and morbidity. Using a simple and pragmatic survey, we demonstrated that significant variations in practice exist with respect to optimal target ranges of SpO2 and PaO2 and optimal strategies to titrate FiO2 to achieve target SpO2 and PaO2. Further preclinical and clinical studies are needed to inform evidence-based guidelines. The results of this survey provide useful avenues to stimulate research that can guide appropriate management of oxygen for treatment of PPHN in neonates.

Acknowledgments

The Nemours Foundation, Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under grant number U54-GM104941 (PI: Binder-Macleod) and NIH COBRE P30GM114736 (PI: Thomas H Shaffer)

References

- 1.Steinhorn RH. Neonatal pulmonary hypertension. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2010;11(2, Suppl):S79–S84. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181c76cdc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Clermont G, Griffin MF, Clark RH. Epidemiology of neonatal respiratory failure in the United States: projections from California and New York. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(7):1154–1160. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.7.2012126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lipkin PH, Davidson D, Spivak L, Straube R, Rhines J, Chang CT. Neurodevelopmental and medical outcomes of persistent pulmonary hypertension in term newborns treated with nitric oxide. J Pediatr. 2002;140(3):306–310. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2002.122730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walsh-Sukys MC, Tyson JE, Wright LL, et al. Persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn in the era before nitric oxide: practice variation and outcomes. Pediatrics. 2000;105(1 Pt 1):14–20. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farrow KN, Groh BS, Schumacker PT, et al. Hyperoxia increases phosphodiesterase 5 expression and activity in ovine fetal pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 2008;102(2):226–233. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.161463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lakshminrusimha S, Swartz DD, Gugino SF, et al. Oxygen concentration and pulmonary hemodynamics in newborn lambs with pulmonary hypertension. Pediatr Res. 2009;66(5):539–544. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181bab0c7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carlo WA, Finer NN, Walsh MC, et al. SUPPORT Study Group of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Target ranges of oxygen saturation in extremely preterm infants. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(21):1959–1969. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0911781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmidt B, Whyte RK, Asztalos EV, et al. Canadian Oxygen Trial (COT) Group. Effects of targeting higher vs lower arterial oxygen saturations on death or disability in extremely preterm infants: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;309(20):2111–2120. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.5555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stenson B, Brocklehurst P, Tarnow-Mordi W U.K. BOOST II trial; Australian BOOST II trial; New Zealand BOOST II trial. Increased 36-week survival with high oxygen saturation target in extremely preterm infants. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(17):1680–1682. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1101319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barbaro RP, Odetola FO, Kidwell KM, et al. Association of hospital-level volume of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation cases and mortality. Analysis of the extracorporeal life support organization registry. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191(8):894–901. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201409-1634OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Konduri GG, Vohr B, Robertson C, et al. Neonatal Inhaled Nitric Oxide Study Group. Early inhaled nitric oxide therapy for termand near-term newborn infants with hypoxic respiratory failure: neurodevelopmental follow-up. J Pediatr. 2007;150(3):235–240. 240.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.11.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosenberg AA, Kennaugh JM, Moreland SG, et al. Longitudinal follow-up of a cohort of newborn infants treated with inhaled nitric oxide for persistent pulmonary hypertension. J Pediatr. 1997;131(1 Pt 1):70–75. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(97)70126-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lakshminrusimha S, Carmen M, Stuewe SR, Goldsmith JP. The evolution of management of late preterm and term neonates with hypoxic respiratory failure: a survey of present practices. J Neonatol Res. 2012;2(2):70–81. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shivananda S, Ahliwahlia L, Kluckow M, Luc J, Jankov R, McNamara P. Variation in the management of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn: a survey of physicians in Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. Am J Perinatol. 2012;29(7):519–526. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1310523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abman SH, Wolfe RR, Accurso FJ, Koops BL, Bowman CM, Wiggins JW., Jr Pulmonary vascular response to oxygen in infants with severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatrics. 1985;75(1):80–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vento M, Asensi M, Sastre J, Lloret A, García-Sala F, Viña J. Oxidative stress in asphyxiated term infants resuscitated with 100% oxygen. J Pediatr. 2003;142(3):240–246. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2003.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vento M, Sastre J, Asensi MA, Viña J. Room-air resuscitation causes less damage to heart and kidney than 100% oxygen. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172(11):1393–1398. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200412-1740OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Belik J, Jankov RP, Pan J, Yi M, Chaudhry I, Tanswell AK. Chronic O2 exposure in the newborn rat results in decreased pulmonary arterial nitric oxide release and altered smooth muscle response to isoprostane. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2004;96(2):725–730. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00825.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heymann T. Clinical protocols are key to quality health care delivery. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 1994;7(7):14–17. doi: 10.1108/09526869410074702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meade MO, Ely EW. Protocols to improve the care of critically ill pediatric and adult patients. JAMA. 2002;288(20):2601–2603. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.20.2601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chow LC, Wright KW, Sola A CSMC Oxygen Administration Study Group. Can changes in clinical practice decrease the incidence of severe retinopathy of prematurity in very low birth weight infants? Pediatrics. 2003;111(2):339–345. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.2.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ellsbury DL, Ursprung R. Comprehensive oxygen management for the prevention of retinopathy of prematurity: the pediatrix experience. Clin Perinatol. 2010;37(1):203–215. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kellerman SE, Herold J. Physician response to surveys. A review of the literature. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20(1):61–67. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00258-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]