Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Rural African Americans are disproportionately impacted by social stressors that place them at risk of developing psychiatric disorders. This study aims to understand mental health from the perspective of rural African American residents and other stakeholders in order to devise culturally acceptable treatment approaches.

METHODS

Seven focus groups (N=50) were conducted with four stakeholder groups. A semi-structured interview guide was used to elicit perspectives of mental health, mental health treatment, and ways to improve mental health within rural African American communities. Inductive analysis was used to identify emergent themes and develop a conceptual model grounded in the textual data.

RESULTS

Stressful living environments (e.g. impoverished communities) and broader community held beliefs (e.g. religious beliefs and mental health stigma) impacted not only perceptions of mental health but also contributed to barriers that impede mental health seeking. Participants also identified community level strategies that can be utilized to improve emotional wellness in rural African American communities.

CONCLUSION

Rural African Americans experience several barriers that impede treatment use. Strategies that include conceptualizing mental illness as a normal reaction to stressful living environments, the use of community-based mental health services, and providing mental health education to the general public may improve use of services in this population.

African Americans living in the rural South are more likely to live in persistent poverty1 (with poverty rates of at least 20% since 1980)2, experience poor educational attainment, fewer economic opportunities, racism, and discrimination3–5. Chronic exposure to such stressors can increase the likelihood of experiencing stress related psychopathology such as depression 6–10. A recent study found that up to 30% of rural African Americans sampled11 reported clinically significant depressive symptoms compared to estimates of 10–19% in other community based studies12. Racial disparities in outcomes show rural African Americans are more likely to experience a higher burden of disability (i.e. increased risk for hospitalization, impairment in occupational and social functioning, etc.) related to mental illness than their white counterparts13;14. Taken together, these data suggest rural African Americans may experience greater stress and an increased risk for mental illness10;15–17.

Rural African Americans are less likely to receive formal mental health treatment when compared to other racial and ethnic groups living in the rural South 15. Numerous structural barriers to timely and adequate mental health care for rural African Americans exist, including lack of insurance, fewer available services, substandard quality services, and greater travel distances 15;16;18–20. Cultural barriers, such as mistrust and fear of treatment, may prove equally as obstructive, placing rural African Americans at risk for experiencing significant levels of functional impairment resulting from unmet psychiatric need.19;21;22

Most efforts to improve mental health care in rural areas focus on improving access to care (telemedicine) or improving quality of care (collaborative mental health services in primary care).23–25 However, these approaches may not be as beneficial to those who may be unlikely to seek formal health care. Therefore, it is important to understand mental health from the perspective of rural African American community members in order to devise culturally acceptable treatment delivery approaches.

Methods

Community Partnership

This study resulted from a partnership between the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) and Tri-County Rural Health Network (TCHRN). The UAMS team consisted of a multi-disciplinary group of faculty (psychiatrist, clinical psychologist, doctoral level nurse, medical sociologist, and medical anthropologist). TCHRN runs a successful program of community health workers (called Community Connectors) linking persons with chronic physical illnesses to resources for home and community-based health services. A 10-member Community Advisory Board (CAB) provided oversight to the project. The CAB consisted of community leaders, college students, mental health providers, community health workers, and persons living with mental illness.

Setting

This study was conducted in Jefferson County, located in the Arkansas Delta. African Americans living in the Arkansas Delta experience negative health outcomes and marked health disparities.26 The mean income of African Americans living in Jefferson County is $36,638 compared to Caucasian’s income of $41,983. African American households are more likely to be headed by a single mother, and 36 % of African American families with children under the age of 18 live below the poverty level. Jefferson County has a relatively strong health care infrastructure, including a mental health clinic and a federally qualified community health clinic.

Recruitment

Four key stakeholder groups relevant to rural African American mental health were identified: primary care providers, faith community, college students and administrators, and individuals living with mental illness. In choosing our stakeholder groups, we considered groups identified in the literature as being important to the African American community in general (clergy), important in this particular location (colleges), important in the health care delivery system (providers), and important for the lived experience of mental illness (individuals living with mental illness). We utilized a snowball recruitment technique where we identified a “key informant” or someone connected to the stakeholder group who then connected us to potential participants or suggested ways (e.g., flyers) to reach out to potential participants.

Interview Procedure and Protocol

Prior to developing the interview guide, the research team, community partners, and CAB worked to determine culturally acceptable language for discussing mental health. Given the stigma associated with the word “mental,” the CAB suggested we use the term “emotional wellness.” The CAB defined emotional wellness as, “a state of health in which an individual can cope with everyday stress and life circumstances.” Following consensus on terms to be used, the research team developed a semi-structured interview guide. This interview guide included probes to encourage discussion about perceptions of emotional wellness and mental illness, current efforts to address mental illness, preferences for both addressing mental illness, and promoting emotional wellness.

We completed two focus groups with healthcare providers (n =16), one focus group with clergy and parishioners (n =6), one focus group with persons living with mental illness (n =10), and one focus group with college students and administrators (n=9). After noting how the inclusion of college administrators stifled the voices of the students, we held an additional focus group with only college students (n=9). All focus groups were conducted between March and May of 2013. Each focus group lasted approximately 90 minutes and was moderated by a member of the academic research team. Focus groups were held in local settings (local church, college office space, medical clinic conference rooms). Participants received $50 to $100 compensation (depending on community or provider status) for participating in the study. Each focus group was recorded and transcribed.

Data Analysis

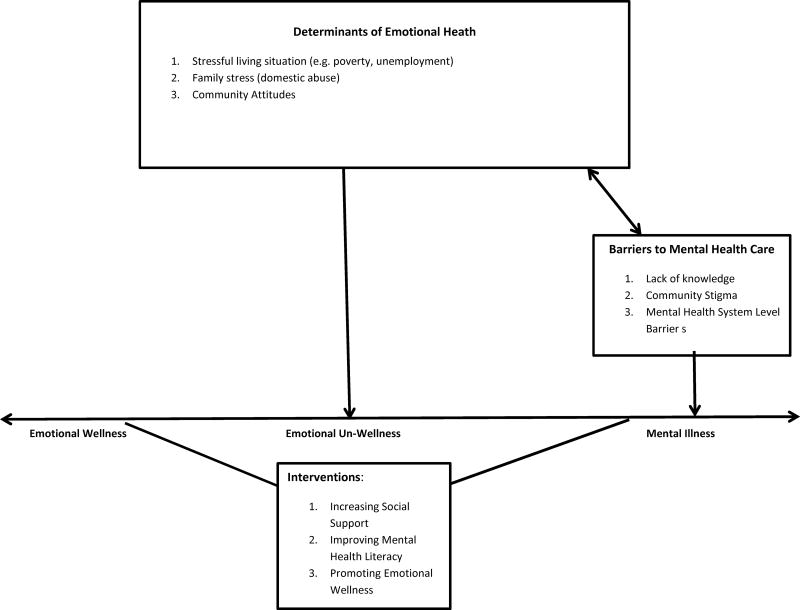

Principles of grounded theory, including theme identification, constant comparison, model building grounded in narrative text, were used to analyze the data27. Each focus group was recorded, transcribed, and imported into MAXQDA, a qualitative data analysis program.28 MAXQDA facilitates organizing, managing, and analyzing text-based data. Analysts developed codes based on the interview guide and used MAXQDA to apply codes and tag related text segments. Analysts then used open-coding to identify emergent themes. A codebook, including thematic code definitions and exemplar quotes, was developed and analysts independently applied the coding schema to the same text to assess inter-coder agreement.29 The qualitative analysts reconciled disagreement and revised the codes until an inter-coder reliability of .80 was reached.30 Analysts then applied the codes to all transcripts. Constant comparison was used to compare and contrast themes within and across focus groups. Themes were reported to the CAB who assisted with the interpretation of the data. Analysts generated a conceptual model that was grounded in the text and provided a comprehensive overview of the relationships between themes (see Figure 1)27;31.

Figure 1.

Model of Overarching Themes

Results

The majority of participants were female (58%), African American (87%), and currently employed (62%). 34% were married and 33% completed some college, and 47% were either currently in mental health treatment themselves or knew of someone who had received formal mental health treatment (see Table 1). Figure 1 delineates how determinants of emotional health influenced both how participants conceptualized mental health and discussions of barriers that impede the use of mental health services. Barriers to mental health service use may often serve to reinforce some determinants of emotional wellness, such as community held beliefs. Participants identified community level strategies that can be used to address mental illness and promote emotional wellness in rural African American communities. Below we explicate the relationships delineated in Figure 1 using participants’ narratives.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics

| Focus Groups (n=50) |

||

|---|---|---|

| N | % | |

| Gender (female) | 28 | 58% |

| Age | ||

| 18–29 | 15 | 31% |

| 30–49 | 16 | 33% |

| 50–59 | 10 | 21% |

| 60+ | 7 | 15% |

| Missing | 2 | |

| Race (African American) | 42 | 88% |

| Education | ||

| Some High School | 3 | 2% |

| High School Graduate | 7 | 15% |

| Some College | 16 | 33% |

| College Graduate | 6 | 13% |

| Graduate School | 16 | 33% |

| Married | 21 | 34% |

| Employed | 30 | 63% |

What is emotional wellness?

When defining mental health, participants tended to think of a spectrum running from emotional wellness (ability to cope with stress) to emotional un-wellness (emotional distress), and at the far end, a diagnosable psychiatric illness.

Emotional Wellness

Participants defined emotional wellness as the “positive management of emotions” when faced with stressful situations. Participants also identified self-esteem as an important characteristic of emotional wellness. One participant stated: “If I’m emotionally well, I feel good about myself. I feel good about where I’m at, and I feel good about the way I work- and I have a real good stepping stone.” Participants identified factors that promote emotional wellness, including social support (i.e. having someone available to listen and offer help and/or advice) and positive outlets (i.e. recreational activities or hobbies) as being particularly important for emotional wellness.

Emotional Un-Wellness

Though only probed about perceptions of emotional wellness and mental illness, participants spontaneously introduced another term: emotional un-wellness. Participants considered emotional un-wellness as “distressed” or “emotionally strained” but not yet as severe as mental illness. Rather, emotional un-wellness was seen as a risk factor for the development of mental illness.

Mental Illness

Most participants perceived mental illness as a serious issue characterized by being “unkempt” and/or “isolated”. Though participants mentioned clinical diagnoses (i.e. depression, schizophrenia, etc.) when asked to describe mental illness, with the exception of the providers, most were unable to identify the signs and symptoms associated with these labels.

Determinants of Emotional Wellness

Stressful Living Environment

Participants readily acknowledged that living in poverty leads to a host of additional stressors such as unstable housing, inability to pay for utilities, and food insecurity that negatively affects emotional health. One participant stated:

“You see a lot of people now that are homeless or either one check away from being homeless. And that increases the stress level which increases anxiety levels, which may lead to other forms of mental health issues because you just think – you’re on the verge of you don’t know whether or not you’re going to have a roof over your head tomorrow. Or you’re working but you know that check is not stretching the way it needs to stretch week to week.”

Family Stress

In addition to the impact of community stressors, participants noted that adverse experiences within the family, such as abuse and neglect, also affected emotional health. One participant stated: “Well, if you got a husband that’s got mental health issues and he may be drinking and in turn he may get abusive with his wife, that may cause her to have issues and it’s just a cycle. Maybe cause her to have depression and everything.”

Feelings of hopelessness

Many participants described how the stress of living in poverty leads to a sense of hopelessness that can negatively impact emotional health. One participant stated: “I think the mentality in our community is very bad. I think we've gotten away -- because things are bad and things are worse in areas of poverty our mentality and our morale has dropped.”

Barriers to Mental Health Treatment

Participants identified mental health treatment as an important and necessary option for addressing mental illness. Untreated mental illness was thought to be associated with increased isolation, criminal activity, and self-medication with drugs and alcohol. Despite the importance of treating mental illness, many indicated that significant barriers impede access to and use of mental health services.

Limited Knowledge about Mental Health

Participants indicated there was a general lack of awareness about mental illness. Participants felt most people didn’t know what mental illness looks like, how to recognize it, or how to identify warning signs of crises. For instance, one participant said, “Yeah, it’s pretty easy to recognize you’re having a heart attack if your chest hurts and you’re short of breath, but if you’ve got some mental illness, like I said, they’re a little tricky. It’s not like you have these set number of symptoms.”

Community Stigma

Stigma remains one of the most important barriers to receiving both formal treatment and informal help-seeking within this community. One participant stated: “It’s sad to say that in the African-American community that we act as if it [mental illness] doesn’t exist, but it does.” Many participants discussed reluctance to seek help for mental health issues due to concerns about a lack of anonymity and fears being labeled crazy or dangerous. In fact, some participants described a reluctance to discuss mental illness with medical providers, “If you’re a diabetic you may go to your physician and say, “Well, diabetes runs in my family,” but if you have a mental… “Well, mental illness runs in my…” You’re not likely to say that to the doctor.”

Mental Health System Level Barriers

The perception was that, for the most part, services are available. However, participants agreed that the mental health care system is more complicated than the physical health care system. Participants identified several improvements that could be made to the service system, such as better mental health screening in primary care, more mental health care provided in primary care, and better quality mental health specialty care.

Addressing mental health needs and promoting emotional wellness

Participants identified three broad types of interventions in addressing mental health needs: providing social support, improving mental health literacy, and promoting emotional wellness.

Social support

Participants highlighted the importance of providing emotional support (i.e. non-judgmental listening). Specifically, participants suggested implementing mentorship programs and support groups for family members of those living with mental illness, as the primary ways to increase social support in rural African American community.

Mental Health Literacy

Participants identified a lack of understanding of the symptoms of mental illness and a lack of awareness of treatment options as major barriers to help-seeking. Many suggested that increasing awareness through education may be an important first step. Education efforts could target everyone in the community but specifically target family members, primary care physicians, and ministers. One participant said, “I also think educating the community on just being mentally healthy, just educating and letting them know it’s not a weakness but it’s about a chemical imbalance and some things you can’t help. Try to help them with coping skills and educate them.”

Promoting Emotional Wellness

Participants indicated it may be helpful to implement interventions aimed at promoting emotional wellness and preventing mental illness. Programs could include providing recreational outlets for individuals, such as community centers offering daily activities. Many also mentioned that updating or cleaning up the parks may be a good start to promote emotional wellness. Participants also discussed the importance of helping individuals cope with common stressors such managing finances, preparing resumes for job searching, and learning to manage other chronic health issues. These may improve an individual’s ability to cope and thereby improve their overall emotional wellness. Spirituality, including both intrinsic belief in God and prayer, was thought to be beneficial to maintaining emotional wellness as it gave individuals a sense of hope and optimism in the face of stress. While participants discussed spirituality as important, they also described some aspects of organized religion may not always be useful in promoting emotional wellness and in some cases may even be detrimental. A participant stated: “You have to be careful…, so we [don’t] look at mental illnesses as demons.”

Discussion

Rural African Americans correctly recognize how social inequities including racism, unemployment, and poverty increase risk for experiencing mental illness. Providing mental health promotion interventions that build individuals abilities to cope with stressful situations (i.e. teaching strategies for coping with racism and poverty) 32 within communities riddled with persistent poverty may be a first step to mediating the negative impacts of poverty related stress on emotional health. Attempts to improve emotional wellness in this population may be more effective if emotional un-wellness is conceptualized as a normal reaction to living under inequitable conditions. Therefore, interventions utilizing sociocultural conceptualizations of mental health that emphasize the role that stress related to one’s minority status plays in the development of mental illness, may be more culturally acceptable.

The most powerful barriers to seeking help were mental health stigma and low mental health literacy. The ability to identify symptoms of mental illness is the first step to seeking timely and appropriate help;33 therefore, this lack of awareness has serious implications for service use. It is challenging for community members to recognize, except in the most extreme cases, that treatment is needed. Even after recognizing a need for treatment, stigma may continue to impede treatment seeking. Participants’ recommendations to improve treatment use, such as providing services in non-clinical settings such as community centers, were in many ways shaped by stigma and concerns about preserving anonymity. Providing care in community settings also provides an opportunity to implement peer-led mental health interventions. For example, peer led interventions for depression and trauma have been found to be effective34;35 and culturally acceptable. Peer-led interventions may also provide opportunities to increase social support, which is a strategy suggested by participants to improve emotional wellness.

Participants also suggest educating the public about mental illness. Mental health education programs, such as Mental Health First Aid (MHFA)36, have been shown to positively impact mental health literacy and stigmatizing attitudes and may be an effective tool to use in rural African American communities.37–40 However, literature suggests that providing both education and contact with a person who has experienced mental illness produces larger and more long-standing impacts on stigmatizing attitudes.39 Thus, adapting MHFA to include contact with individuals living with mental illness may more effectively address both mental health literacy and stigma in this population.

Participants emphasized the usefulness of prayer and other spiritual practices in promoting emotional wellness, which may partly explain noted preferences for pastoral counseling among African Americans41. However, participants also expressed concerns that traditional religious leaders might view mental illness as a spiritual failure rather than a medical illness, which may serve to impede use of formal mental health services. Clinicians working with African American clients should be aware some clients may feel their own spiritual inadequacy has either caused or contributed to their illness. It could be useful for clinicians to become familiar with local pastors who accept a medical model of mental illness so they might enlist the assistance of these clergy members when appropriate to support treatment.42

Limitations

Though our findings provide a rich understanding of how rural African Americans view mental health and mental health treatment, participants in this study tended to be younger and more educated than the larger rural African American population. This is likely a function of the pre-selected stakeholder groups (i.e. college students and administrators and providers) sampled in this study. Further, this study was conducted in the rural South. Thus, these results may not be generalizable to other rural African American subgroups.

Conclusion

Mental health is an important concern among rural African Americans. These results provide important recommendations for developing culturally relevant strategies for improving mental health within rural African American communities.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Alice Deibel, Paul Koegel, Nancy Shoenberg, and Gery Ryan for their advice and guidance on this project.

The research was supported by a pilot study award from the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) #1IP2PI000338-01DS and by the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) Translational Research Institute (TRI) grant UL1TR000039 through the NIH National Center for Research Resources and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences.

All statements in this report, including its findings and conclusions, are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee, or the views of any other funding agency.

Contributor Information

Tiffany F. Haynes, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences - Department of Health Behavior Health Education, College of Public Health, Little Rock, Arkansas

Ann Cheney, University of California Riverside Ringgold standard institution - Center for Healthy Communities, School of Medicine, Riverside, California.

Greer Sullivan, University of California Riverside Ringgold standard institution - Center for Healthy Communities, School of Medicine, Riverside, California; University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences - Psychiatry, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Keneshia Bryant, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences - Department of Health Behavior and Health Education, College of Public Health, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Geoffrey Curran, Central Arkansas Healthcare Systems - VA Health Services Research and Development, Little Rock, Arkansas; University of Arkansas Medical School - Psychiatry, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Mary Olson, Tri County Rural Health Network.

Naomi Cottoms, Tri County Rural Health Network.

Christina Reaves, University of California Riverside Ringgold standard institution - Center for Healthy Communities, School of Medicine, Riverside, California.

Reference List

- 1.Harris RP, Worthen D. African Americans in Rural America. Challenges for rural America in the twenty-first century. 2003:32–42. [Google Scholar]

- 2.United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. Rural Poverty and Well-Being: Geography of Poverty. 2013:2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fitchen JM. On the Edge of Homelessness: Rural Poverty and Housing Insecurity1. Rural Sociology. 1992;57:173–193. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kusmin L. Rural America at a glance. USDA-ERS Economic Brief. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 5.United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. rural america at a glance 2011 edition. 2011 Ref Type: Report. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Odom EC, Vernon-Feagans L. Buffers of Racial Discrimination: Links with Depression among Rural African American Mothers. J Marriage Fam. 2010:346–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00704.x. 2010/07/31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mays VM, Cochran SD, Barnes NW. Race, race-based discrimination, and health outcomes among African Americans. Annual review of psychology. 2007;58:201. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mansfield C, Novick LF. Poverty and Health. NC Med J. 2012;73:366–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Torpy JM, Lynm C, Glass RM. Poverty and health. Jama. 2007;298:1968. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.16.1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mezuk B, Abdou CM, Hudson D, et al. "White Box" Epidemiology and the Social Neuroscience of Health Behaviors The Environmental Affordances Model. Society and mental health. 2013 doi: 10.1177/2156869313480892. 2156869313480892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yeary KH, Ounpraseuth S, Kuo D, et al. Examing the impact of perceived personal health issues and concerns on community identified concerns in community health assessments. Journal of Public Health. In press. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hankerson SH, Lee YA, Brawley DK, Braswell K, Wickramaratne PJ, Weissman MM. Screening for Depression in African-American Churches. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Breslau J, Kendler KS, Su M, Gaxiola-Aguilar S, Kessler RC. Lifetime risk and persistence of psychiatric disorders across ethnic groups in the United States. Psychol Med. 2005:317–327. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704003514. 2005/04/22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Breslau J, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Kendler KS, Su M, Williams D, Kessler RC. Specifying race-ethnic differences in risk for psychiatric disorder in a USA national sample. Psychol Med. 2006:57–68. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006161. 2005/10/06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.New Freedom Commission on Mental Health Care. achieving the promise: transforming mental health care in america. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2003. Ref Type: Report. [Google Scholar]

- 16.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. mental health: culture, race, and ethnicity-- a supplement to mental health: a report of the surgeon general. Rockville, MD: Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services; 2001. Ref Type: Report. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. 2005:629–640. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.629. 2005/06/09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rost K, Fortney J, Fischer E, Smith J. Use, quality, and outcomes of care for mental health: the rural perspective. 2002:231–265. doi: 10.1177/1077558702059003001. 2002/09/11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Snowden LR. Barriers to effective mental health services for African Americans. 2001:181–187. doi: 10.1023/a:1013172913880. 2002/02/28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fox J, Merwin E, Blank M. De facto mental health services in the rural south. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 1995;6:434–468. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cooper-Patrick L, Powe NR, Jenckes MW, Gonzales JJ, Levine DM, Ford DE. Identification of patient attitudes and preferences regarding treatment of depression. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:431–438. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00075.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sussman LK, Robins LN, Earls F. Treatment-seeking for depression by black and white Americans. 1987:187–196. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(87)90046-3. 1987/01/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al. Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines. Impact on depression in primary care. 1995:1026–1031. 1995/04/05. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katon W, Robinson P, Von Korff M, et al. A multifaceted intervention to improve treatment of depression in primary care. 1996:924–932. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830100072009. 1996/10/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miranda J, Duan N, Sherbourne C, et al. Improving care for minorities: can quality improvement interventions improve care and outcomes for depressed minorities? Results of a randomized, controlled trial. 2003:613–630. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00136. 2003/06/06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maulden J, Goodell M, Phillips M. Health Status of African Americans in Arkansas. 2012 6-15-2015. Ref Type: Report. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Sage publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 28.MAXQDA, Software for qualitative data analysis 1989–2012. Berlin, Germany: Sozialforschang GmbH; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 29.MacQueen KM, McLellan E, Kay K, Milstein B. Codebook development for team-based qualitative analysis. Cultural anthropology methods. 1998;10:31–36. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bernard HR, Ryan GW. Analyzing qualitative data: Systematic approaches. SAGE publications; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Charmaz K. Constructivist and objectivist grounded theory. Handbook of qualitative research. 2000;2:509–535. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barry MM, Jenkins R. Implementing mental health promotion. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jorm AF. Mental health literacy. Public knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders. 2000:396–401. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.5.396. 2000/11/04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Houston TK, Cooper LA, Ford DE. Internet support groups for depression: a 1-year prospective cohort study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002 doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.12.2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pistrang N, Barker C, Humphreys K. Mutual help groups for mental health problems: A review of effectiveness studies. American journal of community psychology. 2008;42:110–121. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9181-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. [Accessed June 1, 2015];Mental Health First Aid. Mental Health First AID USA Program Overivew. 2012 http://www mentalhealthfirstaid org/cs/program_overview [serial online]

- 37.Griffiths KM, Christensen H, Jorm AF, Evans K, Groves C. Effect of web-based depression literacy and cognitive-behavioural therapy interventions on stigmatising attitudes to depression: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2004:342–349. doi: 10.1192/bjp.185.4.342. 2004/10/02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jorm AF, Christensen H, Griffiths KM. Changes in depression awareness and attitudes in Australia: the impact of beyondblue: the national depression initiative. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2006:42–46. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01739.x. 2006/01/13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Corrigan PW, Morris SB, Michaels PJ, Rafacz JD, Rüsch N. Challenging the public stigma of mental illness: a meta-analysis of outcome studies. Psychiatric Services. 2012;63:963–973. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Corrigan PW, River LP, Lundin RK, et al. Three strategies for changing attributions about severe mental illness. 2001:187–195. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006865. 2001/05/17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Neighbors HW, Musick MA, Williams DR. The African American minister as a source of help for serious personal crises: Bridge or barrier to mental health care? Health Education & Behavior. 1998;25:759–777. doi: 10.1177/109019819802500606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sullivan S, Pyne JM, Cheney AM, Hunt J, Haynes TF, Sullivan G. The pew versus the couch: Relationship between mental health and faith communities and lessons learned from a VA/clergy partnership project. Journal of religion and health. 2014;53:1267–1282. doi: 10.1007/s10943-013-9731-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]